Abstract

Among the many climate change impacts on the European cattle sector, heatwaves lead to some of the most profound impacts on the sector. It is therefore of utmost importance to estimate to what extent the European cattle sector can be exposed to heatwaves in the near future. Using outcomes of climate models, we analysed how cattle production systems in the wider European Union (EU) region will be exposed to changes in heatwave exposure under two scenarios. We look at both cattle systems, where animals predominantly graze on outdoor pastures, and those where they are kept indoors without access to the outdoors. We show that 6.2–13.7 million cattle livestock units (or 11.0–21.6% of current cattle in the EU and UK) will experience at least 15 additional heatwave days by 2050. This will affect 4.5–11.6% of cattle grazing outdoors compared with 18.3–+35% of cattle kept indoors without access to outdoor grazing. However, there are considerable differences between different countries in the region, with Southern European countries projected to be the most exposed. Our results therefore indicate, adaptation measures specific to different and diverse livestock system types and climatic regions across Europe are necessary for a more climate robust cattle sector in the EU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The European Union’s (EU) cattle sector is important for the income of around 1.3 million agricultural holdings that engage in rearing over 73 million cattle1, making it one of the most important global cattle-producing regions. European cattle producing systems are however, diverse. Just over half (54%) of all cattle in the EU graze on outdoor pastures, with 3.5% grazing in low intensity seminatural areas, such as close to nature grasslands and transitional vegetation2. Of the remaining cattle that are reared in indoor, zero-grazing systems, 29.5% (or 13.6% of the total EU cattle) are housed in intensively managed systems with densities higher than 2 LSU/ha. While such indoor systems are highly efficient3, they also raise concerns regarding the animal welfare of large agricultural holdings and the reliance on imported feed, often from distant places with large environmental impacts4,5. The EU cattle sector is a major emitter of greenhouse gases, contributing 49% of the total agricultural and around 4.9% of the total emissions in the block6. It is also a major nitrogen polluter, with an estimated 45% of emissions related to manure management6. Moreover, the cattle sector has important impacts on the EU’s biodiversity7. All this has resulted in growing demands to lower the environmental impact of the European cattle sector8. At the same time, many traditional cultural European landscapes depend on cattle grazing, which maintains grassland areas, prevents abandonment and can even reduce the risk of wildfires9,10,11,12,13,14. The cattle sector is therefore an important part of the European culture, economy, and diets.

To maintain beef and dairy production, ensure farmer’s livelihoods and decrease the environmental impact of the cattle sector, the EU has ambitious climate change mitigation goals as part of the EU’s Green Deal and related policy instruments within the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Common Agricultural Policy including the target to reduce GHG emissions by at least 55% by 20308,15,16. However, such goals may be difficult to achieve as the effects of climate change also present a major challenge to the EU’s cattle sector, which is among the most vulnerable to climate change. This is due to both the impacts on grassland and other feed production, as well as the direct impacts on the animals due to heatwaves17.

The cattle sector in Europe is facing numerous climate change related challenges, among them increasing occurrence of heatwaves, which have led to large rates of excess mortality as demonstrated in recent years18,19,20. Besides increased mortality, heatwaves impact the European cattle sector by threatening animal comfort and health, reducing reproductive performance and decreasing farm production, which is impacted by decreased feed intake and nutritional imbalances, leading to lower milk productivity17,19. Indirectly, heatwaves can lead to lower crop and grassland yields21,22, which can reduce available feed and increase the costs for agricultural inputs for cattle farmers. The cattle sector can adapt to heatwaves by, for example, providing shade on outdoor pastures, which can help the animals maintain normal panting behaviour and respiration rates23. In indoor systems, adaptation can be more difficult, as the impacts of heatwaves can be exacerbated by higher rates of polluted air, requiring abatement with air conditioning and purification, and ideally by providing more access to outdoor areas or abandoning fully indoor systems24. However, in order to sufficiently plan such measures, information on the extent and spatial distribution of cattle subject to heatwaves in the near future is necessary, especially as Europe has been identified among the global regions where heat stress will most profound impact on cattle mortality and productivity25.

In this study, we estimate the potential extent of cattle subject to increases in heatwaves in the near future. We achieved this by mapping changes in days with health-related heatwaves across the current spatial distribution of cattle in the EU. We considered two scenarios, covering a wide spectrum in terms of greenhouse gas emissions in the future and expected climate change impacts (RCP4.5 and RCP8.5) for the period 2041 to 2060, and compared the results with the current climate (see the Methods for more details). We then analysed the exposure of European cattle to heatwaves for different systems, depending on the prevalence of cattle grazing outdoors, or without access to outdoor pastures, and summarized the findings for individual EU Member States and the United Kingdom.

Results

Differences in exposure between European countries

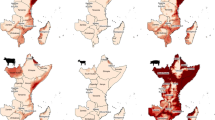

We find that 6.2 to 13.7 million cattle (expressed in livestock units - LSUs) in the studied countries in Europe, or 11.0 to 21.6% of total current cattle, are expected to be subject to 15 or more additional days of heatwaves in the near future under the two scenarios. When looking at exposure greater than 5 additional heatwave days, we observe that 70 to 92% of all European cattle is projected to experience such increases (Figs. S1–S6). Exposure varies considerably across individual Member States and European climatic regions (Figs. 1 and 2), where most of the cattle impacted are found in indoor, zero grazing systems located in southern European, Mediterranean Member States, such as Italy, Greece, Slovenia, Croatia and Spain – 27.2 to 46.4% of all cattle in Mediterranean Member States of the EU are projected to experience profound increases to heat stress. Worryingly, many high-density commercial cattle producing areas, such as the Po valley in northern Italy and Catalonia, where many so called megastable holdings are located (holdings with over 500 cattle LSU)4 will experience more than 15 additional heatwave days compared to today (Fig. 1). We observe similar increases in heatwaves also for medium cattle density (1 to 2 LSU/ha) areas such as those around the Central Massif in France and in the eastern Alps (Austria and Slovenia).

Differences in exposure between indoor and grazing systems

Besides differences in exposure between different countries, we also found that indoor cattle are projected to have greater exposure to future increases in heat stress. Although 4.5 to 11.6% of all cattle with access to outdoor grazing will be impacted by more than 15 additional heatwave days, this is substantially higher when considering cattle kept in indoor systems without access to the outdoors. Under the RCP4.5 scenario, 18.2% of permanently indoor cattle are projected to experience more than 15 additional days with extreme temperatures, with this share increasing to 35.0% under the RCP8.5 scenario.

Differences in exposure between European climatic zones

Accounting for climatic characteristics across Europe, we see that there are considerable differences in projected exposure to future heatwaves between climatic zones of the region (Table 1, Tables S1–S7). Most of the cattle in Atlantic, and Boreal, Nemoral and Alpine North regions of Europe will experience between up to 5 additional days of heatwaves under RCP4.5. Under the more extreme scenario, less than 15% of grazing cattle will experience less than 5 days of additional days with heatwaves in these regions, and up to 37% of indoor cattle in these regions. In the Continental and Lusitanian zone, most of the cattle is projected to be exposed to 5 to 15 additional days with heat stress. Cattle populations in the Alpine South, Pannonian and the Mediterranean regions are projected to be particularly exposed to increases in heatwave (Table 1). More than 75% under RCP4.5 and nearly all cattle under 8.5 are projected to experience more than 15 additional heatwave days in these regions.

Discussion

Timely and adequate adaptation to heatwaves can ensure the stability and socio-economic and environmental sustainability of the European cattle sector. By analysing the exposure of European cattle to future heat stress, we have identified the hotspots and the scale of climate adaptation needs in one of the most important European agricultural sectors. Numerous studies provide evidence on potential increases in exposure of European cattle to heat stress and its impact on cattle productivity26,27, mortality18,20,24, and welfare and comfort19,23. Despite these advancements in estimating heat stress impacts on cattle, continental-scale spatially explicit hotspots of future change throughout the whole European cattle sector remained understudied. A recent study that examined the impact of heat stress on cattle globally28, used data with a coarser spatial and thematic distribution of cattle29,30. In our study, we went beyond changes to average temperatures and focused on the direct exposure to extreme temperatures such as in the case of heatwaves. This makes our results more suitable for Europe, also due to the high diversity of cattle production systems at relatively detailed scales in the region. Our study, presents a novel approach by separating cattle systems into those where outdoor grazing dominates, and those where cattle are kept inside, thereby accounting for the diversity in European cattle rearing systems. When comparing our results to other studies, we also found that cattle systems of Southern, Mediterranean Europe will experience most heat stress in the future, with Boreal and Atlantic parts of the region being subject to less heat stress25,28. In addition, other studies corroborate our findings that high-yielding systems in Europe are particularly vulnerable to heat stress31.

The potential impacts of increasing heatwaves on the European cattle sector will clearly require measures tailored to the characteristics of individual countries and climatic regions (particularly the Mediterranean, the Alps, and other European mountain regions) and to the type of cattle rearing system (mostly indoor systems without access to grazing). Moreover, impacts related to potential losses in production and the economic impact on the livestock sector should be investigated further to estimate the costs to cattle farmers and financial needs for adaptation. However, it is clear from our results, that the holdings with cattle without access to outdoor grazing will be most exposed to future heat stress, presenting an opportunity to transform them to cattle rearing systems with more access to outdoors, which can, besides climate change adaptation, also lead to synergies in animal welfare, landscape preservation and improved sustainability of the cattle sector32. Nevertheless, such systems might have different economic outcomes33,34, and could lead to less feed provided by grasslands due to trampling of animals35,36. In addition, lower density outdoor grazing can have higher emissions per unit of meat or dairy compared to more intensive outdoor and indoor systems37,38. However, while high exposure could potentially lead to decreases in cattle numbers due to decreased productivity, if planned properly, it can present an opportunity for emission reduction goals with simultaneous reductions in exposure to heat stress. Future research should therefore explore potential synergies in climate change adaptation through cattle rearing systems change and a decrease in cattle numbers.

Our results indicate that many of the intensive, large agricultural holdings in the European south will need to invest in climate-proof housing, with changes to water and temperature management of barns, and in some cases, even reductions in cattle numbers39. Adaptation in such systems can, however, be difficult, as heatwaves can lead to lower productivity, and consequently negatively impact the adaptive capacity of agricultural holdings due to decreased income40. Potential impacts of increased heatwaves might be exacerbated due to the fact that many of the areas most impacted - such as the Mediterranean, Alpine, and other mountainous regions - are dominated by old and ageing farmer populations4, which could also be less likely to adapt by changing their farming system.

Methods

Spatial distribution of cattle

We used a recent spatial distribution of cattle for the European Union and the United Kingdom, which maps cattle density and type of system at a 100 m spatial resolution2. Cattle in the data are split into those that spend a considerable amount of time on outdoor pastures in the vegetation period, those that do not have access to outdoor grazing (defined as indoor in this study), and those grazing on seminatural habitats in low densities, such as seminatural pastures, transitional vegetation, and other open areas covered with shrubs and individual trees. We combined cattle grazing in seminatural areas with grazing cattle, as the former represents a small share of cattle in Europe and most individual countries. We refer to both types together as grazing cattle.

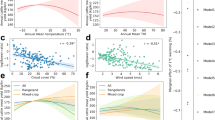

Climate data processing and heat stress estimation

We then processed heatwave data for Europe, derived from climate projections provided by the Copernicus Climate Change Service41. We used data following the definition for health-related heatwave days42, where heatwaves are defined as days in which the maximum apparent temperature (Tappmax) exceeds the 90th percentile of the respective month, and the minimum temperature (Tmin) is greater than the 90th percentile of Tmin of the respective month for at least two days for the period between June to August. This way, the data capture summer heatwaves only, and not also unusually warm days in the winter, spring, and autumn periods. We used the data on the ensemble members' average, which contains bias-adjusted outputs of 8 model combinations of EURO-CORDEX model outputs for Europe, available for the RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 scenarios. Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs) are the most recent climate scenarios developed and used in global climate and environmental research, as well as policy support. This allows comparison with other potential studies and studying the context of global climate change impact research. The two studied RCPs are relevant, as they present a spectrum for two different emission levels. RCP4.5 is a future scenario, where greenhouse gas emissions and radiative forcing stabilize by 2100, thereby presenting a scenario with climate change mitigation43. The second scenario, RCP8.5, is characterized by high greenhouse gas emissions due to a lack of climate change mitigation policies44. The two scenarios therefore, present contrasting climate change impacts in terms of type, intensity, and the spatial extent of impacts. This combination of scenarios is useful to study a wider range of potential impacts of heat stress on European cattle that can also be described as medium (RCP4.5) and high or extreme (RCP8.5).

We first calculated the average number of heatwave days per year for the current climate, represented by the period 1986-2010 (as these are years based on observed days of heatwaves). We then calculated the average number of heatwave days per year for the period 2041 to 2060 for both scenarios, roughly corresponding to the period around the year 2050. We then overlaid the processed data with the cattle distribution data and calculated differences between the current climate and the two future scenarios. We performed our analysis on the scale of whole of the whole region, individual Member States and the United Kingdom, and individual European climatic zones, using the typology for European climatic stratification45 (Fig. S11). This way, we were also able to estimate the impacts in different climatic regions. The resulting maps indicate the number of additional days with heat stress. All processing was performed using QGIS46.

Data availability

All the data used are freely accessible. The cattle distribution data are accessible at https://zenodo.org/records/13734518. Current and projected heatwave data are accessible at https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/sis-heat-and-cold-spells?tab=overview.

Code availability

No additional code was generated, and standard operations available in geographic information systems software were used.

References

EUROSTAT. Main livestock indicators. https://doi.org/10.2908/EF_LSK_MAIN (2025).

Malek, Ž et al. Improving the representation of cattle grazing patterns in the European Union. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 114077 (2024).

Faverdin, P., Guyomard, H., Puillet, L. & Forslund, A. Animal board invited review: Specialising and intensifying cattle production for better efficiency and less global warming: contrasting results for milk and meat co-production at different scales. Animal 16, 100431 (2022).

Debonne, N. et al. The geography of megatrends affecting European agriculture. Glob. Environ. Change 75, 102551 (2022).

Escobar, N. et al. Spatially-explicit footprints of agricultural commodities: Mapping carbon emissions embodied in Brazil’s soy exports. Glob. Environ. Change 62, 102067 (2020).

Levasseur, S. Reducing EU cattle numbers to reach greenhouse gas targets. Rev. OFCE 183, 181–216 (2023).

Crenna, E., Sinkko, T. & Sala, S. Biodiversity impacts due to food consumption in Europe. J. Clean. Prod. 227, 378–391 (2019).

Guyomard, H., Soler, L.-G., Détang-Dessendre, C. & Réquillart, V. The European Green Deal improves the sustainability of food systems but has uneven economic impacts on consumers and farmers. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–14 (2023).

Malek, Ž et al. Mapping livestock grazing in semi-natural areas in the European Union and United Kingdom. Landsc. Ecol. 39, 31 (2024).

Halada, L., Evans, D., Romão, C. & Petersen, J.-E. Which habitats of European importance depend on agricultural practices?. Biodivers. Conserv. 20, 2365–2378 (2011).

Plieninger, T. et al. Wood-pastures of Europe: Geographic coverage, social–ecological values, conservation management, and policy implications. Biol. Conserv. 190, 70–79 (2015).

García-Ruiz, J. M., Lasanta, T., Nadal-Romero, E., Lana-Renault, N. & Álvarez-Farizo, B. Rewilding and restoring cultural landscapes in Mediterranean mountains: Opportunities and challenges. Land Use Policy 99, 104850 (2020).

Hadjigeorgiou, I., Osoro, K., Fragoso de Almeida, J. P. & Molle, G. Southern European grazing lands: Production, environmental and landscape management aspects. Livest. Prod. Sci. 96, 51–59 (2005).

Pillar, V. D. & Overbeck, G. E. Grazing can reduce wildfire risk amid climate change. Science 387, eadu7471 (2025).

EC. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: REPowerEU Plan. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:52022DC0230 (2022).

EC. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Reions: The European Green Deal. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640&qid=1737711930432 (2019).

Godde, C. M., Mason-D’Croz, D., Mayberry, D. E., Thornton, P. K. & Herrero, M. Impacts of climate change on the livestock food supply chain; a review of the evidence. Glob. Food Secur. 28, 100488 (2021).

Morignat, E. et al. Assessment of the Impact of the 2003 and 2006 Heat Waves on Cattle Mortality in France. PLOS ONE 9, e93176 (2014).

Polsky, L. & von Keyserlingk, M. A. G. Invited review: Effects of heat stress on dairy cattle welfare. J. Dairy Sci. 100, 8645–8657 (2017).

Vitali, A. et al. The effect of heat waves on dairy cow mortality. J. Dairy Sci. 98, 4572–4579 (2015).

Carozzi, M., Martin, R., Klumpp, K. & Massad, R. S. Effects of climate change in European croplands and grasslands: productivity, greenhouse gas balance and soil carbon storage. Biogeosciences 19, 3021–3050 (2022).

Ciais, P. et al. Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437, 529–533 (2005).

Laer, E. V. et al. Effect of summer conditions and shade on behavioural indicators of thermal discomfort in Holstein dairy and Belgian Blue beef cattle on pasture. animal 9, 1536–1546 (2015).

Egberts, V., van Schaik, G., Brunekreef, B. & Hoek, G. Short-term effects of air pollution and temperature on cattle mortality in the Netherlands. Prev. Vet. Med. 168, 1–8 (2019).

North, M. A., Franke, J. A., Ouweneel, B. & Trisos, C. H. Global risk of heat stress to cattle from climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 094027 (2023).

Gauly, M. & Ammer, S. Review: Challenges for dairy cow production systems arising from climate changes. animal 14, s196–s203 (2020).

Gauly, M. et al. Future consequences and challenges for dairy cow production systems arising from climate change in Central Europe - A review. Animal 7, 843–859 (2013).

Thornton, P., Nelson, G., Mayberry, D. & Herrero, M. Impacts of heat stress on global cattle production during the 21st century: a modelling study. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e192–e201 (2022).

Gilbert, M. et al. Global cattle distribution in 2015 (5 min of arc). [object Object] https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LHBICE (2022).

Gilbert, M. et al. Global distribution data for cattle, buffaloes, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, chickens and ducks in 2010. Sci. Data 5, 180227 (2018).

Hempel, S. et al. Heat stress risk in European dairy cattle husbandry under different climate change scenarios – uncertainties and potential impacts. Earth Syst. Dyn. 10, 859–884 (2019).

Bielza, M., Weiss, F., Hristov, J. & Fellmann, T. Impacts of reduced livestock density on European agriculture and the environment. Agric. Syst. 226, 104299 (2025).

van der Voort, M. et al. Economic modelling of grazing management against gastrointestinal nematodes in dairy cattle. Vet. Parasitol. 236, 68–75 (2017).

Shortall, O. K. & Lorenzo-Arribas, A. Dairy farmer practices and attitudes relating to pasture-based and indoor production systems in Scotland. PLOS ONE 17, e0262268 (2022).

Horn, J. & Isselstein, J. How do we feed grazing livestock in the future? A case for knowledge-driven grazing systems. Grass Forage Sci. 77, 153–166 (2022).

Pulido, M., Schnabel, S., Lavado Contador, J. F., Lozano-Parra, J. & González, F. The Impact of Heavy Grazing on Soil Quality and Pasture Production in Rangelands of SW Spain. Land Degrad. Dev. 29, 219–230 (2018).

Gerber, P., Vellinga, T., Opio, C. & Steinfeld, H. Productivity gains and greenhouse gas emissions intensity in dairy systems. Livest. Sci. 139, 100–108 (2011).

Gerssen-Gondelach, S. J. et al. Intensification pathways for beef and dairy cattle production systems: Impacts on GHG emissions, land occupation and land use change. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 240, 135–147 (2017).

Gaughan, J. B., Sejian, V., Mader, T. L. & Dunshea, F. R. Adaptation strategies: ruminants. Anim. Front. 9, 47–53 (2019).

Escarcha, J. F., Lassa, J. A. & Zander, K. K. Livestock under climate change: a systematic review of impacts and adaptation. Climate 6, 54 (2018).

Copernicus C. C. S. Heat waves and cold spells in Europe derived from climate projections. Copernicus Climate Change Service. ECMWF https://doi.org/10.24381/CDS.9E7CA677 (2019).

WHO. Improving public health responses to extreme weather/heat-waves: EuroHEAT: technical summary. World Health Organization report. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/107935 (2009).

Thomson, A. M. et al. RCP4.5: a pathway for stabilization of radiative forcing by 2100. Clim. Change 109, 77 (2011).

Riahi, K. et al. RCP 8.5—A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim. Change 109, 33 (2011).

Metzger, M. J., Bunce, R. G. H., Jongman, R. H. G., Mücher, C. A. & Watkins, J. W. A climatic stratification of the environment of Europe. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 14, 549–563 (2005).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project (2023).

Acknowledgements

This research has received funding by the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency (grant J4-50224 “Land-based climate changemitigation and adaptation”), and by the European Union’s Horizon Europe Research and Innovation programme (grant 101060423 “LAnd use and MAnagement modelling for SUStainable governance”).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Ž.M. designed the research, processed and analysed the data, wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared the figures. L.S. designed the research and wrote the main manuscript text. Both authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Ž.M. is a member of the Editorial Board of this journal. Ž.M. did not handle the manuscript and did not have any role in the review process of the paper.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malek, Ž., See, L. Future heatwave exposure of the European cattle sector. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 6 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00113-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00113-w