Abstract

Agrivoltaic systems, which integrate agricultural production with photovoltaic energy generation, have garnered attention for their dual-use potential. However, few studies have addressed yield variability of major staple crops, and their morphological and physiological traits in agrivoltaic systems. This study investigated yield performance and shade avoidance responses of three major Asian staple crops, rice, soybean, and sweet potato in agrivoltaic systems. We also assessed the influence of cultivation management practices, such as cultivar selection, weed control, and micronutrient fertilization, which have been overlooked in previous studies, using organically grown sweet potato. Field experiments for rice, soybean, and sweet potato were conducted in 2024, while organic sweet potato experiments in 2023–2024. Our findings revealed substantial inter- and intraspecific variation in yield responses to shading. Rice grain yield remained stable under 27% shading, whereas soybean seed yield decreased by 30% under 33% shading. Conventional sweet potato tuber yield decreased by 40% under 31% shading and further under 49% shading. Organic sweet potato tuber yield in different cultivars decreased by 26–51% in 2023 and 18–65% in 2024 under 40% shading. All crops exhibited shade avoidance responses in agrivoltaic systems, such as increased plant height and elevated shoot-to-root ratios. Among sweet potato cultivars, the degree of yield reduction was linked to the intensity of shade avoidance responses. In contrast, neither weed control timing nor micronutrient fertilization significantly affected yield. These findings underscore the importance of understanding crop- and cultivar- specific morphological and physiological responses to ensure stable production in agrivoltaic systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Agrivoltaic systems (AVSs), also known as solar sharing systems, integrate agriculture with photovoltaic (PV) energy generation on the same land1,2,3. First proposed in the 1980s4, the concept gained practical momentum in the 2000s to address land-use conflicts between large solar farms and agriculture2,5,6. In many cases, the revenue from electricity surpasses that from agricultural production5,7,8. However, some countries require AVSs to maintain adequate crop productivity to qualify for land-use approval9. For example, in Japan, one of the requirements for implementing AVSs is that the crop yield on farmland beneath photovoltaic panels must not decrease by more than approximately 20% compared with the regional average yield for the same year10. Therefore, maintaining crop yield under shading beneath photovoltaic panels is important.

Numerous studies have examined the effects of AVSs on yields, predominantly focusing on horticultural crops such as vegetables and fruits11. Moreover, research findings on horticultural crops are inconsistent, with studies reporting both crop gains and losses11. Moderate shading (20–30%) often has little to no negative impact on vegetables. Fruit yield may improve production by reducing heat and drought stress. For instance, field trials involving leafy greens such as broccoli and cabbage have reported no significant differences in yield between AVS plots and open-field controls12,13. Conversely, intense shading led to yield losses. Magarelli et al.14. found that shading levels of up to approximately 30% are generally not detrimental to fruit yield and quality, whereas higher shading levels are associated with yield reductions.

The effects of AVSs on the main crops (cereals, legumes, maize, and tubers) are highly variable and often more complex than those observed in horticultural crops11,15. Many main crops have elevated light requirements and low shade tolerance, making them susceptible to yield decline due to panel shading. Although there are fewer studies on main crops than horticultural crops, several studies have investigated their yield responses. For example, experiments with winter wheat in Europe demonstrated yield variations ranging from a 3% increase to a 29% decrease when utilizing panel arrays2,16. Several studies have examined rice, and many have reported yield reductions17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Trials across multiple locations in East Asia have typically reported yield reductions of 0–30%. Similarly, research on maize and legumes has indicated yield reductions in AVSs with considerable variability7,25,26. However, research on these crops is limited. Notably, studies on sweet potatoes, despite their extensive global cultivation, spanning 75.7 million hectares and yielding 93.5 million tons in 202327, are scarce. Considering that main crops account for a large proportion of global agricultural land, it is essential to investigate AVS conditions that facilitate adequate production.

Yield reductions in AVSs may arise from both direct decreases in photosynthesis and the shade avoidance response (SAR), which indirectly lowers yields. The SAR refers to a set of physiological and morphological changes that plants undergo in response to reduced light availability28, typically involving stem and petiole elongation, increased plant height, and reduced leaf expansion29,30. These responses enable plants to compete for light but often result in the allocation of resources from belowground and reproductive organs to aboveground organs, potentially resulting in reduced grain or tuber yields31,32. Crops with strong SAR may experience more substantial yield losses under AVS shading than those with a greater shade tolerance. Therefore, variations in shade tolerance among crops may be influenced by differences in SAR strength. Overall, the physiological and morphological mechanisms that influence the main crop performance under AVS shading remain poorly understood11. This knowledge gap, especially regarding the traits that confer shade tolerance in main crops, underscores the need for additional research on AVSs.

Despite the promising potential of AVSs, there is a notable lack of studies focusing on actual AV farms operated by farmers (as estimated from Widmer et al.11). Most existing research has been conducted under controlled experimental conditions with ideal fertilization and weed management. Therefore, the effects of farming practices (e.g., weeding, fertilizer application, tillage, and pesticide use) adopted by farmers on AVS farming remain underexplored. In addition, few studies have investigated the performance of different cultivars under AVS conditions11. These gaps highlight the need for comprehensive field studies to assess the performance of different crop species/varieties and farming practices under on-farm AVS conditions (Fig. 1).

This study aimed to improve AVSs for main crops by addressing the following key objectives:

-

1.

Quantify the effects of AVSs on the yields of rice, soybeans, and sweet potatoes.

-

2.

Examine the relationship between yield reduction and shade avoidance responses.

-

3.

Investigate the effects of cultivars, weed control timing, and micronutrient fertilization on organically grown sweet potatoes under AVS and open-field conditions.

Results

The statistical analysis results are summarized in Tables S1 and S2. The microclimate conditions are summarized in Tables S3 and S4, while complete microclimate data are contained in the supplemental csv files.

Rice (conventional)

Except for the lacking data, air temperature was generally lower in the AVS than in the control, with daily mean and maximum values reduced by 0.2 and 0.7 °C, respectively. Water temperature exhibited larger declines, with daily mean and maximum values decreasing by 0.9 and 1.97 °C, respectively (Table S3).

Grain yield did not differ significantly between the AVS and control treatments (GLM, p > 0.05; n = 6 AVS and n = 4 control). Mean yields were 5.5 ± 0.3 and 5.8 ± 0.6 t ha⁻¹ for the AVS and control plots, respectively (mean ± SD, scaled from plot yields; Fig. Fig. 2a). However, the AVS significantly affected several yield-related traits (Table 1). The number of panicles per hill was significantly lower in the AVS, while the number of spikelets per panicle increased. The percentage of filled grains did not differ significantly between the AVS and control. The 1000-grain weight was significantly higher in the AVS than in the control. In the AVS, the 50% heading date was delayed by 5 days. Plant height was, on average, 9.7 cm higher in the AVS than in the control (Fig. 2b). Aboveground biomass was significantly lower in the AVS (Table 1). The crude protein content of brown rice was higher in the AVS than in the control (Table 1).

Soybean (conventional)

Air temperature was generally lower in the AVS than in the control (Supplementary Table S4), with the daily mean being 0.25 °C lower. Mean soil temperature was 0.6 °C lower, whereas soil water content was 0.7% higher in the AVS.

Seed yield was reduced by 31% in the AVS compared with that in the control (2.0 vs. 2.9 t ha⁻¹ on average; Fig. 3a). (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 10 AVS and n = 8 control). Mean yields were 2.0 ± 0.5 and 2.9 ± 0.6 t ha⁻¹ for the AVS and control plots, respectively (Fig. 3a).

Among morphological and yield components, plant height was on average 6.9 cm higher in the AVS, whereas branch number decreased by 3.2 (Fig. 3b, c). The main stem diameter, numbers of nodes, pods and seeds, percentage of filled pods, and 100-seed weight were all significantly lower in the AVS than in the control (Table 2). Aboveground biomass also decreased significantly in the AVS. Crude protein, sugar, and fat contents did not differ significantly between treatments (Table 2).

Sweet potato (conventional)

Air temperature was generally lower in the low-shading AVS than in the control (Table S4). The daily mean was 0.38 °C lower. Mean soil temperature was also 1.0 °C lower in the AVS.

Tuber yield (estimated from tuber weight per plant) decreased by 40% in the low-shading AVS treatment compared to that in the control (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 10 plants per treatment). Mean tuber weight per plant were 1018.9 ± 470 g and 612.5 ± 239 g for the AVS and control plots, respectively (Fig. 4a).

a Tuber weight per plant, b Length of vines, c Total biomass weight, d Aboveground fresh weight/underground fresh weight (T/R) ratio. *, **, and *** indicate significance at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively; ns: not significant. We did not perform statistical analysis on the 49% shading experiment of conventional sweet potato because this site lacked a control site that shared the same ridge. In addition, the planting date was different from that of both the 31% shading site and its control site.

At harvest, the longest vine length was on average 72 cm longer in the low-shading AVS than in the control (Fig. 4b); however, the number of branches on the longest vine was consistent across groups (Fig. S1a, b). The total biomass weight, number of tubers, and total underground weight (roots + tubers) decreased significantly in the low-shading AVS compared to those in the control (Fig. 4c, Fig. S1b, c), whereas total aboveground weight remained unchanged (Fig. S1d). The T/R ratio increased in the low-shading AVS (Fig. 4d), a trend that remained consistent across monthly surveys conducted at 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 DAP (Fig. S2). No statistical analyses were performed for the high-shading site; however, yield-related traits were generally lower, and the T/R ratio was higher than in the low-shading site (Fig. S2).

Sweet potato (organic)

In 2023 experiment (AVS × four cultivars × weeding treatments), tuber yield decreased by 42% in the AVS treatment compared to the control (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 288 plants for each treatment). Mean tuber weight per plant were 724.7 ± 547 g and 1243 ± 850 g for the AVS and control plots, respectively. The results showed a significant interaction between treatment (AVS vs. control) and variety in terms of yield (tuber weight) in 2023 (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 72 plants per treatment and variety; Fig. 5a).

The impact of AVS on the yield of organic potato differed according to the cultivars. Three of four cultivars (Anno, Beniharuka, and Silksweet) exhibited yield reductions in the AVS, whereas the yield of one cultivar, Karayutaka, did not differ between the AVS and control (Fig. 5a).The first weed control timing did not significantly affect yield, while only the treatment itself was significant (p < 0.05; Fig. S3).

At harvesting time, the longest vine length was significantly longer in the AVS than in the control in 2023 (Fig. 5b). The number of branches on the longest vine did not differ between them (Fig. S4a). Total biomass weight of only one cultivar, Anno, was reduced in the AVS (Fig. 5c). The number of tubers and total underground weight (including roots and tubers) decreased significantly in the AVS compared to that in the control (Fig. S4b, c); however, the impact of the AVS on total aboveground weight and T/R ratio differed based on cultivars (Figs. S4d, 6d). The total aboveground weights of three cultivars (Beniharuka, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) increased significantly in the AVS, whereas one cultivar, Anno, did not decrease (Fig. S4d). The T/R ratios of three cultivars (Anno, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) increased significantly in the AVS, whereas the T/R ratio of one cultivar, Beniharuka, did not differ (Fig. 5d).

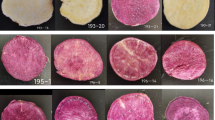

In 2024 experiment (AVS × five cultivars × fertilizer treatments), tuber yield decreased by 49% in the AVS treatment compared to the control (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 180 plants for each treatment). Mean tuber weight per plant were 355.0 ± 341 g and 694.6 ± 504 g for the AVS and control plots, respectively. The results showed a significant interaction between treatment (AVS vs. control) and variety on yield in 2024 (GLMM, p < 0.05; n = 54 plants per treatment and variety for Amahazuki, Anno, and Beniharuka and n = 9 plants per treatment and variety for Karayutaka and Silksweet; Fig. 6a).

Two of five cultivars (Anno and Beniharuka) exhibited yield reductions in the AVS, whereas the yield of three cultivars (Amahazuki, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) did not differ between the AVS and control. Additionally, the impact of micronutrient fertilizer on yield was not significant (Fig. S5), with only the treatment showing significance (p < 0.05).

At harvesting time, the longest vine length was significantly longer in the AVS than that in the control (Fig. 6b). Total biomass weight was reduced in the AVS for all cultivars (Fig. 6c). The number of branches of one cultivar, Amahazuki, decreased in the AVS, whereas that of Beniharuka increased in the AVS (Fig. S6a). The interaction between variety and treatment on the number of tubes was not significant (Fig. S6b); therefore, we did not compare them based on cultivar. The interactions between variety and treatment on the total underground weight and T/R ratio were significant (Figs. S6c, 6d). The interaction between variety and treatment on total aboveground weight was not significant (Fig. S6d).

The total underground weight of two cultivars (Anno and Beniharuka) decreased in the AVS, whereas that of three cultivars (Amahazuki, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) remained unchanged (Fig. S6c). The T/R ratio of two cultivars (Anno and Beniharuka) increased significantly in the AVS, whereas that of three cultivars (Amahazuki, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) did not differ (Fig. 6d). This variation was linked to yield differences among cultivars (Fig. 6a).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the impact of on-farm AVSs with different shading levels on three staple crops: rice, soybean, and sweet potato. AVS effects on yield differed among crops: rice grain yield was not significantly reduced in AVS (27% shading), whereas soybean yield decreased by an average of 31% under 33% shading. Conventional sweet potato tuber yield decreased by 40% under 31% shading, and organic sweet potato tuber yield decreased by 42% in 2023 and 49% in 2024 under 40% shading (Figs. 2a, 3a, 4a, 5a, 6a).

Our rice results contrasted with those of previous studies that indicated yield reductions under panels17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. This discrepancy may be attributed to several factors. First, we used a glutinous rice cultivar, which could respond differently from the non-glutinous cultivars examined previously. Second, compensatory responses among yield components might have mitigated yield loss in the AVS. Although the number of panicles decreased in the AVS, which was consistent with previous studies, the overall yield appeared to have been offset by increases in the number of spikelets per panicle and 1000-grain weight (Table 1). These contrasting responses imply that shading in the vegetative stage adversely affects certain yield components, whereas shading in the later growth stages may yield positive effects. Several studies have also shown that rice yield losses caused by shading during the vegetative stage may be compensated for by the increase in grain number and grain weight per spikelet33,34.

Third, weather and microclimate conditions may account for the lack of yield differences between the AVS and control. In a six-year experiment, Thum et al.8 showed that rice yield (AVS/control) varied with annual weather, and in low-precipitation years, no significant reduction was observed. The 1-year duration of our rice trial limits our ability to assess interannual variation. However, 2024 weather conditions may minimize the yield differences between the AVS and control. According to the Japan Meteorological Agency, the summer of 2024 (June–August) was exceptionally hot, with temperatures 1.76 °C above the long-term average. Our study showed that air and water temperatures were lower in the AVS (Table S3). This is consistent with previous reports8,16,35,36,however also refer to Marrou et al. 37,Gonocruz et al. 202117, and Lee et al.20. This cooling effect of the paddy field may confer a relative advantage for rice cultivation under AVS conditions. Elevated water and soil temperatures during the late growth stage are known to impair rice production and quality38,39, and cooling via continuous irrigation is often recommended40. Therefore, AVSs may provide an effective cooling strategy to mitigate heat stress; however, further research is required to evaluate this possibility.

Grain protein content was significantly higher in the AVS than in the control (Table 1), aligning with findings from previous studies8,17,23. High protein levels reduce stretchiness and color quality; therefore, a level below 8% is recommended in Japan (Hokkaido Research Organization, 2004). In our study, the protein content in AVS remained below this threshold.

Our soybean results are consistent with those of previous studies showing a yield reduction in AVSs18,20,41, although Jo et al.18 reported no change in one of the two years studied. Reductions in the number of branches, nodes per plant, pods per plant, and seeds per plant in AVS (Table 2), as reported by Jo et al.18, likely contributed collectively to the yield decline.

Similar to the responses of other tubers to shading15,42,43, AVS substantially reduced sweet potato tuber yield in this study. In our conventional sweet potato cultivation, yield generally decreased as shading intensity increases. These results are consistent with those of a previous study by Oswald et al.44, who documented a linear decrease in yield under experimental light reductions of 0%, 26%, 42%, and 60%. In organic cultivation, lower soil nutrient availability and increased weed competition are expected in organic cultivation. However, we did not observe a lower yield of organic sweet potatoes compared to conventional cultivation (Figs. 4a, 5a, 6a), probably because of differences in soil fertility at the sites. Nonetheless, the combined effects of AVS-induced shading and other environmental stresses on yield remain an important topic for future investigation.

Jin et al.45 demonstrated that the yield of a specific purple sweet potato cultivar remained stable under 20% shading by nets, while it decreased under 40%, 60%, and 80% shading conditions. In our study, the yield of conventional sweet potato decreased by 40% under 31% shading.

Numerous crops have retained SAR as an evolutionary legacy46; however, the role of SAR in AVS remains underexplored. Shade avoidance can reduce reproductive yield via both direct and indirect pathways. Directly, SAR drives resource allocation toward vegetative growth at the expense of reproductive organs, thereby reducing yield. Indirectly, morphological changes associated with SAR, such as reduced tillering and branching, altered leaf development, and increased T/R ratio, can lead to increased risk of lodging and reduced weed suppression, both of which contribute to lower yields32,46,47.

In our study, all three crops, namely rice, soybean, and sweet potato, exhibited clear evidence of SAR in the AVSs (Figs. 2–6). These responses coincided with reduced total biomass (Tables 1–2; Figs. 4c, 5c, 6c). These findings suggest that both reduced photosynthesis and SAR may contribute the observed yield losses. In sweet potato, we identified a link between the magnitude of SAR and cultivar-specific yield reduction (Fig. 6a, d), indicating that SAR is an important trait influencing varietal performance in AVSs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to highlight the role of SAR in crop performance in AVSs.

In rice, we observed typical SAR under AVS conditions, including increased plant height and decreased panicles (Fig. 2b, c). These results are consistent with those of some previous studies8,19, although other research has reported inconsistent results17,18,20. Shading is known to reduce culm diameter and wall thickness, thereby increasing the risk of lodging in rice48. However, no lodging wasprinte observed in our experiment, likely because of the high lodging tolerance reported for the glutinous rice cultivar ‘Fusanomochi’. This may elucidate the absence of a decline in rice yield under AVS conditions in our study, in contrast to findings from other studies reporting lodging8,22. These findings suggest that selecting rice cultivars with reduced SAR or higher lodging tolerance could be crucial for stable production.

For soybeans, previous studies have reported inconsistent results regarding SAR in the AVS. Lee et al.20. demonstrated stem elongation at only one of two study sites, while no differences were observed at the other site. Jo et al.18 observed stem elongation and a decreased number of branches in one of the two study years, with no differences observed in the other year. One study reported that the diameter of the main stem decreased in the AVS20. Those inconsistent results may be attributed to cultivar differences. Soybeans are known to exhibit SAR, typically characterized by increased stem elongation and reduced branching49,50. However, shade-tolerant cultivars exist, with studies in intercropping systems showing that such cultivars generally maintain higher productivity under shaded conditions compared to susceptible ones51,52. The cultivar used in this study, ‘Fukuyutaka,’ was shade-susceptible and prone to lodging53. Accordingly, it showed marked stem elongation and reduced branching under AVS conditions (Fig. 3b, c). To mitigate the negative effects of SAR and optimize yield under shading, several strategies have been proposed, such as selecting for shade-tolerant cultivars54 and implementing effective weed control measures50. These approaches, originally formulated for intercropping systems, are also applicable to AVSs.

For sweet potato, we observed clear SAR under AVS conditions in both conventional and organic cultivation systems, including increased shoot length and shoot-to-root (T/R) ratio (Figs. 4b, d, 5b, d, 6b, d). These findings are broadly consistent with those of previous studies in the context of experimental shading conditions44,45.

Furthermore, our study revealed substantial variation among cultivars in the extent of SAR in AVSs. Notably, the degree of SAR appeared to be associated with yield reduction in AVSs. For example, two cultivars, Anno and Beniharuka, showed increased T/R ratios in AVSs, a typical SAR, and significant reductions in yield (Fig. 6d). In contrast, three cultivars, namely Amahazuki, Karayutaka, and Silksweet, exhibited no significant change in T/R ratio in AVSs (Fig. 6d). Additionally, their yields were not significantly reduced (Fig. 6a). Among these, Amahazuki, which was included only in the 2024 trial, exhibited no yield difference between the AVSs and control and recorded the highest yield among all five cultivars. Amahazuki was developed by the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO) in 2023 and is characterized by its high yield and strong sweetness immediately after harvest. These findings suggest that SAR may play a critical role in cultivar-specific yield performance in AVSs. Further research is required to clarify the physiological mechanisms underlying cultivar differences in yield reduction and resource allocation under AVS shading.

Overall, our findings suggest that crop yield reduction under AVS shading can result from decreased leaf photosynthesis under shading34,55 and SAR. Therefore, crop varieties with strong shade tolerance are useful for AVSs. Generally, elevated auxin and gibberellin levels contribute to the strength of the SAR56 and associated yield reduction31,32. The yield differences observed among cultivars under AVS may reflect genetic variation in the biosynthesis of these hormones and downstream signaling pathways. To better understand the mechanisms linking SAR and yield reduction in AVSs, further studies on resource allocation and plant hormone involvement are needed.

Most AVS crop studies conducted to date have taken place in experimental fields, where the growing conditions are presumably more uniform and ideal than those found in farmer-managed environments. As a result, the influence of farming practices, including weed control and fertilization, on crop growth and yield under AVS conditions has remained largely unexamined. In organically managed AVS systems, weed control is likely to be particularly critical because organic farming typically involves higher weed pressure. Additionally, shading conditions have been shown to exacerbate weed competition, thereby negatively impacting crop productivity. For example, Colbach et al.57 suggested that weed harmfulness increased with higher plant height at later stages when shading was more likely to occur. Colbach et al.58 indicated that weeds exhibited a greater response to shade than that of crops, resulting in increased specific leaf area, leaf biomass ratio, and plant height and width per unit biomass. Therefore, weeds are likely to compete for light with crops more intensively in AVSs than in open fields.

For sweet potato production, some studies have suggested that the timing and duration of weed control are crucial factors influencing sweet potato yield59,60,61. Harrison and Jackson60 investigated the effects of varying durations of weed interference on two cultivars and revealed that a cultivar with an erect shoot growth habit exhibited reduced susceptibility to weeds and achieved higher yields in unweeded plots than a cultivar with a spreading growth habit. Cooper et al.58,59 assessed the critical weed-free period for three sweet potato cultivars and determined that a threshold of less than 10% total yield loss was achieved by maintaining weed-free conditions 20–33 DAP, depending on cultivars. Levett60,61 showed that delaying the onset of weeding beyond 14 DAP resulted in yield reduction. Nevertheless, our findings from organically managed sweet potato fields indicate that weed control timing did not influence yield in either the AVS or control plots. (Fig. 5b). Several factors may account for this. First, plastic black mulch was employed, demonstrating effectiveness in weed management within organic sweet potato fields62 and successfully suppressing weeds across all treatments. Second, the weed control timing established in this study was unlikely to affect the yields. The increasing adoption of AVS has led to the concept of conservation agrivoltaics, which incorporates conservation agriculture practices within AVS systems63. In this context, effective weed management under solar panels is anticipated to emerge as a key issue.

Micronutrient fertilization did not affect yield in either the AVS or control plots (Fig. 6b). Fertilizers that adhered to organic farming standards contained silica dioxide, trace minerals, and nematophagous fungi. Because they did not contain nitrogen, which facilitates plant growth, their effects on yield appeared to be negligible, although the micronutrient components may have influenced sweet potato quality. When fertilizers that facilitate plant growth are applied to AVSs, their effects may differ from those in open fields. Several studies have indicated that lower soil temperatures adversely affect nitrogen mineralization of manure in soils64,65. The observed decrease in air temperature in AVSs (Tables S3 and S4) suggests that fertilizer efficacy in AVSs may differ from that in open fields. Further research is required to evaluate suitable fertilizer applications in AVSs.

Since main crops account for a large proportion of global agricultural land, the adoption of AVSs for their cultivation has attracted increasing attention as a potential solution to land-use conflicts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the link between shade avoidance responses and AVS-induced yield variation across multiple crops and cultivars. These findings underscore the importance of trait-based crop and cultivar selection for successful AVS implementation, particularly under organic and low-input conditions. As noted by Widmer et al.11. and Williams9, defining the optimum daily light integral (DLI) for each species is required to implement an optimal AVS in a region. Moreover, cultivars with shade tolerance-related traits, including shorter plant stature, higher tiller number, and suitability for higher planting or seeding densities may also be potential candidates for AVSs.

The main limitation of this study was the relatively small sample size within a single season for conventional rice, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. As yield variations in AVSs can be influenced by many factors, including climate and successive agricultural practices, further studies should be conducted across multiple years.

This study investigated the yield and SAR for three main staple crops in Asia, namely rice, soybean, and sweet potato, in AVSs. We also examined the effects of cultivar differences, weed control, and fertilization, factors that have been largely overlooked in previous AVS research, using organically grown sweet potato as a case study. Our findings revealed substantial interspecific variation in yield responses across crop species, ranging from no significant reduction in rice to a 49% decrease in organic sweet potato, despite similar shading levels. Moreover, we demonstrated for the first time that yield reductions varied significantly among cultivars and were linked to the intensity of SAR.

These findings highlight the importance of assessing not only yield outcomes but also the underlying morphological and physiological responses, particularly mechanisms behind SAR, to support stable crop production under AVS conditions.

Methods

General field experiment design

All field experiments were conducted on farms managed by farmers in Chiba Prefecture, Japan, under agrivoltaic system (AVS) and control (open field) conditions. Environmental data, including air temperature, soil temperature, and moisture, luminosity, and precipitation, were continuously monitored at the conventional rice, soybean, and sweet potato sites using a sensor (Kisyo Sensor, Farmo Inc., Utsunomiya City, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan). Sensors were installed both under the AVSs and in adjacent control plots 1.5 m above the ground, and data were recorded every 5–10 min. The shading rate is defined as the ratio of the area shaded by the panels to the area of land used for the AVSs. The tilt angles of the panels remained constant throughout the growing season. Fertilization, pest, and weed management followed local standard practices, unless stated otherwise.

Rice (conventional)

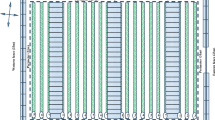

Glutinous rice (Oryza sativa L., var. Fusanomochi) was cultivated in 2024 in a gray lowland soil in Chiba City (Figs. 1a, 7a–c; 35°38′N, 140°12′E, 13.4 m asl). The average temperature in this region was 18.0 °C, with total precipitation measuring 1634.5 mm in 2024, as observed by the Automated Meteorological Data Acquisition Systems in Chiba City. Monocrystalline bifacial PV panels (31.8 kg per unit; 2.3 × 1.1 m; LR5-72HBD-550M, LONGi Solar Technology Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used. In total, 144 PV panels (372 m2) with a capacity of 79.2 kWp were installed in the AVS. The shading rate provided by the panels was 27%, which was defined as the ratio of the area shaded by the panels to the area of land used for the AVSs. The tilt angle of the PV panels was set at 10◦ and orientated towards the southwest and positioned at a height of 4.3 m above the ground at the midpoint of their width. We selected four and six representative positions in the control and AVS treatment as sample plots. The sampling area located beneath AVSs was positioned centrally within the panel rows. The size of each plot was 1 m2 (1 × 1 m).

a Map of Japan. The circle shows the location of Chiba Prefecture. b Map of Chiba Prefecture. The points denote the survey sites. c Field trial design of rice in the agrivoltaic system (AVS) and control. d Field trial design of conventional sweet potato in the AVS and control. e Field trial design of soybean in the AVS and control. f Field trial design of organic sweet potato in the AVS and control. Blue or yellow ranges show the survey area. Black ranges show the AVS sites. The maps of Japan and Chiba prefecture, and photos were modified based on the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan website (https://maps.gsi.go.jp).

Germinated seeds were sown in nursery trays on 5 April and 2–3 seedlings were transplanted into the paddy field at a hill spacing of 30 × 20 cm (16.7 hills m-2) on May 2. The harvesting date for rice was August 29. We monitored the water temperature and water level every 16 min using a sensor (Suiden Farmo, Farmo Inc., Utsunomiya-city, Tochigi Prefecture, Japan) in the AVS and control.

We recorded the dates of 50% heading for each plot. The plant heights were measured for three hills per plot at maturity to assess the SAR. The percentage of lodging was not measured due to the absence of lodging at the study site. Three randomly selected hills from each plot were cut at ground level and measured for yield components, including the number of panicles per hill, number of spikelets per hill, percentage of filled grains, and 1000-grain weights. The percentage of filled grains was defined as the number of spikelets that sank in tap water divided by the total number of spikelets. The grain weights per hill were measured, and the grain yield was adjusted to a moisture content of 14%. The brown rice samples from each plot were sent to Japan Food Research Laboratories to determine the crude protein contents using the combustion method. The straws were oven-dried at 80 °C for 100 h to determine the aboveground dry weights.

Soybean (conventional)

Soybean (Glycine max L., var. Fukuyutaka) was cultivated in 2024 in Chiba City (Figs. 1b, 7a, b, d; 35°30′N, 140°14′E, 76.7 m asl). The soil was classified as Andosol, with a pH (H2O) of 6.3, 1 g nitrate N kg-1, 1 mg Truog-P kg-1, 41 cmolc exchangeable K kg-1, and a cation-exchange capacity of 24 cmolc kg-1. Soybean was cultivated for the first time at the study site. Monocrystalline bifacial PV panels (18.5 kg per unit; 1.6 m × 0.99 m; YL280P-29b, Yingli Green Energy Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used. In total, 100 PV panels (163 m2) with a total capacity of 60 kWp were installed in the AVS. The shading rate provided by the panels was 33%. The relative radiation in the AVS was 0.349. The tilt angle of the PV panels was set at 10◦ and orientated towards the northwest and positioned at a height of 3.7–3.9 m above the ground at the midpoint of their width. The study site was divided into two treatments: a southern area containing commercial mycorrhizal fungus and northern area devoid of it. The treatment was considered a random effect in the analysis because of the absence of replicates. The sampling areas beneath AVSs were positioned centrally within the panel rows.

Soybean seeds (var. Fukuyutaka) were directly sown in the field on July 29, 2024. Seeds were sown at a spacing of 70 cm between rows and 15 cm between hills within the rows, with two seedlings per hill. A commercial controlled-release fertilizer (Ca = 500 kg ha-1) was uniformly applied across the field prior to sowing, and commercial nodule bacteria for soybean (400 g ha-1; Mamezo, Tokachi Agricultural Co., Obihiro City, Hokkaido Prefecture, Japan) were mixed with soybean seeds before sowing. A commercial mycorrhizal fungus (400 g ha-1; Rootella, Shima trading Co., Ltd., Chuo Ward, Tokyo, Japan) was applied prior to sowing in the southern half of the field across the AVSs and control. The harvesting date for soybean was November 28, 2024.

We selected 8 and 10 representative sample plots in the AVS treatment and control groups, respectively. Each plot measured 1 m2 (1 × 1 m). Crude protein, sugar, and fat contents were estimated using a near-infrared transmittance grain analyzer (InfratecTM 1241, FOSS, Hilleroed, Denmark) for all seeds in each plot. Soybean plants were manually harvested from each plot to assess yield. One representative plant per plot was used to measure the aboveground biomass, diameter of main stem, plant height, number of branches, number of nodes, number of pods, percentage of filled pods, number of seeds, and 100-seed weights.

Sweet potato (conventional)

Sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L., var. Beniharuka) was cultivated at two sites with different shading intensities (31% and 49%; hereafter referred to as low and high shading, respectively) in 2024. Sweet potatoes were cultivated for the first time at two study sites. The soil was classified as Andosol, with a pH (H2O) of 6.2, 2 g nitrate N kg-1, 2 mg Truog-P kg-1, 62 cmolc exchangeable K kg-1, and a cation-exchange capacity of 23 cmolc kg-1). The relative radiation in the low shading AVS was 0.737. A low shading site was located in Chiba City, Chiba Prefecture, Japan (Figs. 1c, 7a, b, e; 35°30′N, 140°14′E, 76.7 m asl). In the low shading AVS, monocrystalline bifacial PV panels (31.8 kg per unit; 2.3 × 1.1 m; LONGi Solar Technology Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used. In total, 190 PV panels (491 m2), with capacity of 104.5 kWp were installed in the AVS. The tilt angle of the PV panels was set at 10◦ and orientated towards the southwest and positioned at a height of 4.4 m above the ground at the midpoint of their width. The high shading site was located 400 m from the low-shading site (Figs. 1c, 7a, b, e; 35°30′N, 140°14′E, 57.4 m asl). This site lacked a control in the same field. In the high shading AVS, monocrystalline monofacial PV panels (18.6 kg per unit; 1.7 × 0.99 m; Trina Solar Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used. In total, 2826 PV panels (4626 m2), with capacity of 777 kWp were installed in the AVS. The relative radiation in the AVS was 0.06. The tilt angle of the PV panels was set at 10◦ and orientated towards the northwest and positioned at a height of 4.0–4.2 m above the ground at the midpoint of their width. Time series data on sweet potato growth were obtained by randomly sampling 10 plants from the 0% shading site, which shared rows with the low shading site and nine plants from the high shading site at intervals of 30, 60, 90, 120 and 150 days after transplanting (DAP).

Sweet potato seedlings (var. Beniharuka) were planted in the holes of plastic black mulch on May 25, 2024, at the low-shading site and control and on May 27, 2024, at the high-shading site. Seedlings were spaced 130 cm apart between rows and 30 cm apart within the rows. A commercial controlled-release fertilizer (N-P2O5-K2O = 30-30-30 kg ha-1) was applied prior to planting at the two sites. We conducted a monthly sampling (30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 DAP) to assess the following traits: the number of tubers, total weight of tubers, total underground weight including roots and tubers, longest vine length, number of branches on the longest vine, and total aboveground weight (including vines, leaves and petioles per plant). The aboveground fresh weight/underground fresh weight (T/R) ratio was calculated for each plant.

Sweet potato (organic)

Organic sweet potato was grown in a gray lowland soil field in Noda City (Figs. 1d, 7a, b, f; 36°03′N, 139°48′E, 9.8 m asl) for two years (2023–2024). Monocrystalline PV panels (26.5 kg per unit, 2.2 × 1.0 m; Tiger Bifacial 445-465, Jinko Solar Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were used. In total, 192 PV panels (420 m2), with capacity of 86.4 kWp were installed in the AVS. The shading rate provided by the panels was 40% and the relative radiation in the AVS was 0.64 in 2023 and 2024. The tilt angle of the PV panels was set at 20◦ and orientated towards the south and positioned at a height of 4 m above the ground at their highest point. The panel’s tilt angle of 20° remained constant throughout the growing season. No fertilizer was applied to the site.In 2023, we conducted a survey to assess the effects of first weed control timing and shading by panels on the growth and yield of four sweet potato cultivars (var Beniharuka, Anno, Karayutaka, and Silksweet) to determine optimal weed control timing and suitable varieties for AVS. Three weed control timings in 30 cm on each side of the rows were set for this experiment. The 25% timing weeding referred to the first weeding conducted when weeds covered 25% of the side. Similarly, 50% timing weeding indicated the first weeding is performed after weeds covered 50% of the side, while 100% timing weeding denoted that the first weeding was carried out after weeds covered 100% of the side. The second weeding was conducted three weeks after the first weeding. In the AVS and control, we established eight plots for 25%, 50% and 100% weeding timing for each cultivar, totaling 192 plots. Each plot consisted of 5 plants. Seedlings were planted in the holes of the plastic black mulch on May 31, 2023. Seedlings were spaced 120 cm apart between rows and 30 cm apart within rows. In the AVS treatment, we conducted 25% timing weeding on June 19, 50% timing weeding on June 13 and 14, and 100% timing weeding on July 5–7. In the control, we conducted 25% timing weeding on June 14 (15 DAP), 50% timing weeding on June 19 (20 DAP), and 100% timing weeding on June 26 (27 DAP).

We harvested sweet potatoes from October 23 to November 18. In the AVS treatment, we measured the longest vine length for one middle plant in each plot and the following traits for three middle plants in each plot to avoid edge effects: the number of branches on the longest vine, total aboveground weight (including vines, leaves, and petioles per plant), number of tubers, total weight of tubers, total underground weight (including roots and tubers), and aboveground fresh weight/underground fresh weight (T/R) ratio. We assessed the same traits for three middle plants in the control as well. Dead plants were excluded from the measurements. In 2024, we conducted a survey to assess the impact of micronutrient fertilization and shading by panels on the growth and yield of five sweet potato cultivars (var Beniharuka, Anno, Karayutaka, Silksweet, and Amahazuki) to identify the most suitable cultivar and effectiveness of micronutrient fertilizer in AVS. Each of the AVSs and control comprised 10 shared rows. A micronutrient fertilizer (mine green, Yahata Kyougyou Inc., Tanagura Town, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan) containing 55.0% SiO2, 13.0% Al2O3, 4.1% Fe2O2, 3.6% CaO, 1.6% MgO, 1.1% S, and 15 additional minerals was applied at 180 kg/10a and soil conditioner (AG Doryoku, i-Agri Corp., Tokyo, Japan) containing nematophagous fungi and 60–70% SiO2 soil conditioner was applied at 72 kg/10a to six rows, and the other four rows served as untreated controls. In both the AVS and control, we established 10 and 8 plots for the fertilizer treatment and untreated control, respectively, for each of the three cultivars: Beniharuka, Anno, and Amahazuki. For the other two cultivars, Karayutaka and Silksweet, three plots were established under the fertilizer treatment only, with no plots designated for the untreated control. Each plot consisted of 5 plants. We fertilized on May 23, followed by the planting of seedlings in the holes of the plastic black mulch on June 5, 2024. Seedlings were spaced 120 cm apart between rows and 30 cm apart within rows. Weeding was carried out every two weeks after transplanting.

We harvested sweet potatoes from October 29 to November 23. We measured the longest vine length and number of branches on the longest vine for one middle plant in each plot and the following traits for three middle plants in each plot to avoid edge effects: the number of branches on the longest vine, total aboveground weight (including vines, leaves and petioles per plant), number of tubers, total weight of tubers, total underground weight (including roots and tubers), and T/R ratio. We assessed the same traits for three middle plants in the control as well.

Statistical analysis

Generalized linear models (GLMs) and generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) were employed for analyses using R v 4.5.167. The statistical models utilized for each experiment are summarized in Table S1. We did not perform statistical analysis on the high shading (49%) experiment of the conventional sweet potato due to the absence of a control site on the same ridge. Additionally, the planting date was different from that of both the 31% shading and its control sites. The likelihood ratio test was used to determine the significance of the results using the “car” package.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available in the repository, https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.c59zw3rnq.

References

Dinesh, H. & Pearce, J. M. The potential of agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 54, 299–308 (2016).

Dupraz, C. et al. Combining solar photovoltaic panels and food crops for optimising land use: towards new agrivoltaic schemes. Renew. Energy 36, 2725–2732 (2011).

Weselek, A. et al. Agrophotovoltaic systems: applications, challenges, and opportunities. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 39, 35 (2019).

Goetzberger, A. & Zastrow, A. On the coexistence of solar-energy conversion and plant cultivation. Int. J. Sol. Energy 1, 55–69 (1982).

Mamun, M. A. et al. A review of research on agrivoltaic systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 161, 112351 (2022).

Touil, S., Richa, A., Fizir, M. & Bingwa, B. Shading effect of photovoltaic panels on horticulture crops production: a mini review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 20, 281–296 (2021).

Sekiyama, T. & Nagashima, A. Solar sharing for both food and clean energy production: Performance of agrivoltaic systems for corn, a typical shade-intolerant crop. Environments - MDPI 6, 65 (2019).

Thum, C. H., Okada, K., Yamasaki, Y. & Kato, Y. Impacts of agrivoltaic systems on microclimate, grain yield, and quality of lowland rice under a temperate climate. Field Crops Res. 326, 109877 (2025).

Williams, H. J., Wang, Y., Yuan, B., Wang, H. & Zhang, K. M. Rethinking agrivoltaic incentive programs: a science-based approach to encourage practical design solutions. Appl. Energy 377, 124272 (2025).

MAFF (2024) Permission for farmland conversion to install renewable energy generation facilities (in Japanese). https://www.maff.go.jp/j/nousin/noukei/totiriyo/attach/pdf/einogata-12.pdf (Accessed October 18, 2025).

Widmer, J., Christ, B., Grenz, J. & Norgrove, L. Agrivoltaics, a promising new tool for electricity and food production: a systematic review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 192, 114277 (2024).

Chae, S. H., Kim, H. J., Moon, H. W., Kim, Y. H. & Ku, K. M. Agrivoltaic Systems Enhance Farmers’ Profits through Broccoli visual quality and electricity production without dramatic changes in yield, antioxidant capacity, and glucosinolates. Agronomy 12, 1415 (2022).

Moon, H. W. & Ku, K. M. Impact of an agriphotovoltaic system on metabolites and the sensorial quality of cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) and its high-temperature-extracted juice. Foods 11, 498 (2022).

Magarelli, A., Mazzeo, A. & Ferrara, G. Fruit crop species with agrivoltaic systems: a critical review. Agronomy 14, 722 (2024).

Laub, M., Pataczek, L., Feuerbacher, A., Zikeli, S. & Högy, P. Contrasting yield responses at varying levels of shade suggest different suitability of crops for dual land-use systems: a meta-analysis. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 42, 51 (2022).

Weselek, A. et al. Agrivoltaic system impacts on microclimate and yield of different crops within an organic crop rotation in a temperate climate. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 41, 59 (2021).

Gonocruz, R. A. et al. Analysis of the rice yield under an agrivoltaic system: a case study in Japan. Environments MDPI 8, 1–18 (2021).

Jo, H. et al. Comparison of yield and yield components of several crops grown under agro-photovoltaic system in Korea. Agriculture 12, 1–13 (2022).

Kawamata, M., Kuwabara, Y., Tatsumi, K., Tajima, R. & Nasukawa, H. Effects of agrivoltaic systems panels on rice productivity. Tohoku J. Crop Sci. 65, 17–18 (2022).

Lee, H. J., Park, H. H., Kim, Y. O. & Kuk, Y. I. Crop cultivation underneath agro-photovoltaic systems and its effects on crop growth, yield, and photosynthetic efficiency. Agronomy 12, 1842 (2022).

Suzuki, Y., Ishikawa, M., Iwasaki, K. & Kamiji, Y. Evaluation of rice productivity in solar-sharing paddy fields. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 91, 253–254 (2022).

Nasukawa, H., Kuwabara, Y., Tatsumi, K. & Tajima, R. Rice yield and energy balance in an agrivoltaic system established in Shonai plain, northern Japan. Sci. Total Environ. 959, 178315 (2025).

Park, S.-W., Yun, S.-M., Seong, D.-G., Lee, J. J. & Chung, J.-S. Rice yield and electricity production in agro-photovoltaic systems. Chil. J. Agric. Res. 84, 674–685 (2024).

Tomari, S., Taniguchi, T. & Shinogi, Y. Survey of paddy rice growth in Agrivoltaic-systems. Jpn. Soc. Irrig. Drain. Rural Eng. 91, 157–163 (2023).

Grubbs, E. K. et al. Optimized agrivoltaic tracking for nearly-full commodity crop and energy production. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 191, 114018 (2024).

Potenza, E., Croci, M., Colauzzi, M. & Amaducci, S. Agrivoltaic system and modelling simulation: a case study of soybean (Glycine max L.) in Italy. Horticulturae 8, 1160 (2022).

FAOSTAT (2025) Crops and livestock products. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL. Accessed: July 31, 2025.

Ballaré, C. L. & Pierik, R. The shade-avoidance syndrome: Multiple signals and ecological consequences. Plant Cell Environ. 40, 2530–2543 (2017).

Schmitt, J., Mccormac, A. C. & Smith, H. A test of the adaptive plasticity hypothesis using transgenic and mutant plants disabled in phytochrome-mediated elongation responses to neighbors. Am. Nat. 146, 937–953 (1995).

Schmitt, J., Dudley, S. A. & Pigliucci, M. Manipulative approaches to testing adaptive plasticity: phytochrome-mediated shade-avoidance responses in plants. Am. Nat. 154, S43–S54 (1999).

Shafiq, I. et al. Crop responses and management strategies under shade and drought stress. Photosynthetica 59, 664–682 (2021).

Wille, W., Pipper, C. B., Rosenqvist, E., Andersen, S. B. & Weiner, J. Reducing shade avoidance responses in a cereal crop. AoB Plants 9, plx039 (2017).

Kobata, T., Sugawara, M. & Takatu, S. Shading during the early grain filling period does not affect potential grain dry matter increase in rice. Agron. J. 92, 411–417 (2000).

Song, S. et al. Effects of shading at different growth stages with various shading intensities on the grain yield and anthocyanin content of colored rice (Oryza sativa L.). Field Crops Res 283, 108555 (2022).

Barron-Gafford, G. A. et al. Agrivoltaics provide mutual benefits across the food–energy–water nexus in drylands. Nat. Sustain. 2, 848–855 (2019).

Barron-Gafford, G. A. et al. Agrivoltaics as a climate-smart and resilient solution for midday depression in photosynthesis in dryland regions. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 32 (2025).

Marrou, H., Guilioni, L., Dufour, L., Dupraz, C. & Wery, J. Microclimate under agrivoltaic systems: is crop growth rate affected in the partial shade of solar panels? Agric. For Meteorol. 177, 117–132 (2013).

Nagata, K., Kodani, T., Yoshinaga, S. & Fukuda, A. Effects of water managements during the early grain-filling stage on grain fissuring in rice. Tohoku J. Crop Sci. 48, 33–35 (2005).

Xiong, D., Ling, X., Huang, J. & Peng, S. Meta-analysis and dose-response analysis of high temperature effects on rice yield and quality. Environ. Exp. Bot. 141, 1–9 (2017).

Morita, S., Wada, H. & Matsue, Y. Countermeasures for heat damage in rice grain quality under climate change. Plant Prod. Sci. 19, 1–11 (2016).

Kim, S., Kim, S. & Yoon, C. Y. An efficient structure of an agrophotovoltaic system in a temperate climate region. Agronomy 11, 1584 (2021).

Artru, S., Lassois, L., Vancutsem, F., Reubens, B. & Garré, S. Sugar beet development under dynamic shade environments in temperate conditions. Eur. J. Agronomy 97, 38–47 (2018).

Schulz, V. S. et al. Impact of different shading levels on growth, yield and quality of potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Agronomy 9, 330 (2019).

Oswald, A., Alkäumper, J. & Midmore, D. J. The effect of different shade levels on growth and tuber yield of sweet potato: I. Plant development. J. Agron. Crop. Sci. 173, 41–52 (1994).

Jin, Z. et al. Effects of shading intensities on the yield and contents of anthocyanin and soluble sugar in tubers of purple sweet potato. Crop. Sci. 63, 3013–3024 (2023).

Ruberti, I. et al. Plant adaptation to dynamically changing environment: The shade avoidance response. Biotechnol. Adv. 30, 1047–1058 (2012).

Casal, J. J. Shade avoidance. Arabidopsis Book 10, e0157 (2012).

Wu, L. et al. Shading contributes to the reduction of stem mechanical strength by decreasing cell wall synthesis in japonica rice (Oryza sativa L.). Front. Plant Sci 8, 881 (2017).

Green-Tracewicz, E., Page, E. R. & Swanton, C. J. Shade avoidance in soybean reduces branching and increases plant-to-plant variability in biomass and yield per plant. Weed Sci 59, 43–49 (2011).

Lyu, X., Mu, R. & Liu, B. Shade avoidance syndrome in soybean and ideotype toward shade tolerance. Mol. Breed. 43, 31 (2023).

Gong, W. Z. et al. Tolerance vs. avoidance: two strategies of soybean (Glycine max) seedlings in response to shade in intercropping. Photosynthetica 53, 259–268 (2015).

Liu, W. et al. Relationship between cellulose accumulation and lodging resistance in the stem of relay intercropped soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.]. Field Crops Res. 196, 261–267 (2016).

Uchino, H., Uozumi, S., Touno, E., Kawamoto, H. & Deguchi, S. Soybean growth traits suitable for forage production in an Italian ryegrass living mulch system. Field Crops Res. 193, 143–153 (2016).

Lyu, X. et al. GmCRY1s modulate gibberellin metabolism to regulate soybean shade avoidance in response to reduced blue light. Mol. Plant 14, 298–314 (2021).

Mu, H. et al. Long-term low radiation decreases leaf photosynthesis, photochemical efficiency and grain yield in winter wheat. J. Agron. Crop Sci. 196, 38–47 (2010).

Yang, C. & Li, L. Hormonal regulation in shade avoidance. Front. Plant. Sci. 8, 1527 (2017).

Colbach, N., Gardarin, A. & Moreau, D. The response of weed and crop species to shading: which parameters explain weed impacts on crop production? Field Crops Res. 238, 45–55 (2019).

Cooper, E. G. et al. Evaluation of critical weed-free period for three sweetpotato (Ipomoea batatas) cultivars. Weed Sci. 72, 267–274 (2024).

Harrison, H. F. & Jackson, D. M. Response of two sweet potato cultivars to weed interference. Crop Protection 30, 1291–1296 (2011).

Levett, M. P. Effects of various hand-weeding programmes on yield and components of yield of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas) grown in the tropical lowlands of Papua New Guinea. J. Agric. Sci. 118, 63–70 (1992).

Nwosisi, S., Nandwani, D. & Hui, D. Mulch treatment effect on weed biomass and yields of organic sweetpotato cultivars. Agronomy 9, 190 (2019).

Time, A. et al. Conservation agrivoltaics for sustainable food-energy production. Plants People Planet 6, 558–569 (2024).

Eghball, B., Wienhold, B. J., Gilley, J. E. & Eigenberg, R. A. Mineralization of manure nutrients. J. Soil Water Conserv. 57, 470–473 (2002).

Deressa, A. Effects of soil moisture and temperature on carbon and nitrogen mineralization in grassland soils fertilized with improved cattle slurry manure with and without manure additive. J. Environ. Hum. 2, 1–9 (2015).

R. Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2025).

Acknowledgements

We thank Takashi Sasaki, Tsunagu Farm Inc., and Associate Agri Inc. for his technical assistance in the field experiments. This study was funded by JST, grant number JPMJRS22I8, and Associate Agri Inc. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: N.M., H.T., K.T., M.A. and Y.F.; Investigation: N.M., M.N., H.T., and K.T.; Analysis: N.M. and M.A.; Writing—original draft: N.M. and Y.F.; writing—Supervision: H.K. and Y.F. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maruyama, N., Nozawa, M., Tomioka, H. et al. On-farm agrivoltaic impacts on main crop yield: the roles of shade avoidance, cultivation practices, and varieties. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00121-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-025-00121-w