Abstract

Precision agriculture (PA) is widely presented as a solution to the contemporary problem of feeding the world while conserving natural resources and limiting environmental harms. In this review paper, we summarize the field trial evidence demonstrating that PA use leads to environmental benefits. We systematically reviewed 444 English-language academic publications on PA and sustainability, we found 54 papers that present field-trial or modeling evidence, of which 45 demonstrated environmental benefits during field trials including: reduced fertilizer use; reduced herbicide or pesticide use; reduced water use or contamination (e.g., runoff); improved soil quality; or reduced GHG emissions or fuel consumption. The most evidence exists for variable rate technologies in grain farming, which showed decreased fertilizer use compared to control or universal applications. Our analysis also reveals that some academics make claims about PA and sustainability without presenting adequate evidence. More research is needed which defines sustainability models and metrics, then empirically tests PA along these metrics across a range of agricultural systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Feeding the world while conserving natural resources is a critical global challenge1. Technological innovation is often proposed as the best approach to meeting this global challenge2,3,4. At the same time, intensification of agricultural practices—via mechanization, engineered seed technologies, and synthetic fertilizers—has brought unintended negative environmental consequences5,6,7,8. There is extensive literature demonstrating the link between specific practices in food production, such as the use of pesticides and synthetic fertilizers, and environmental harms, such as biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions9,10,11,12,13. In an era of climate change, erratic weather, and water scarcity, we must address environmental degradation from food production as an urgent mandate for science and policy.

Amidst this reality, “precision agriculture (PA) techniques appear as a feasible option to help solve these problems,” namely “the need to produce more and better-quality food, climate change, urban growth and unsustainable agricultural practices” 14. The formal definition of PA adopted by the International Society of PA is:

A management strategy that gathers, processes and analyzes temporal, spatial and individual data and combines it with other information to support management decisions for improved resource use efficiency, productivity, quality, profitability and sustainability of agricultural production15.

The PA strategy uses monitoring of agronomic variables16 recorded via near and remote sensing (e.g. soil sensors and satellite imagery respectively), along with big datasets and algorithms that generate field- and site-specific advice. Detailed digital maps can be created to display inter- and intra-field variability of the farm features under consideration, so that farmers can make precise decisions based on the particular characteristics of each plot. Some refer to PA as a new agricultural “paradigm” 17.

While, as the definition above indicates, PA adoption might lead to a variety of economic, social, and food quality benefits; in this paper we focus on the claim that PA improves environmental outcomes. PA’s environmental sustainability benefits are widely asserted in popular media and corporate advertising18,19,20,21,22, as well academic literature16,23,24,25,26. A 2004 review article by Bongiovanni and Lowenberg-DeBoer in the journal Precision Agriculture asserted that “the concepts of PA and sustainability are inextricably linked,” with optimism that “PA should reduce environmental loading”24. Over 1280 papers (per Google Scholar) cite Bongiovanni and Lowenberg-DeBoer to support the assertion that PA has environmental sustainability benefits. Over the past two decades, numerous scholars have restated the “inextricable link” phrase verbatim.

Despite apparent consensus that PA leads to environmental sustainability, few systematic analyses summarize the empirical evidence demonstrating that PA adoption leads to positive environmental outcomes. This gap has been identified10 but has yet to be adequately filled27. In 2016, Brown et al. called for such a review, writing how “little empirical research has been conducted to estimate actual changes in the environmental impacts of PAT versus conventional agriculture production” 27. Again, in 2020, Belaine et al. called for such a study, writing, “claims [about PA] must be further verified through rigorous empirical assessment. To the best of our knowledge, the current empirical literature provides limited indication as to which technologies can help resolve the sustainable intensification challenge” 28. Some papers, such as a recent review by Green et al., summarize the potential environmental benefits from PA29. Many papers use mathematical modeling to predict PA’s positive environmental outcomes. But do PA practices, when deployed on the ground, actually deliver environmental benefits?

It is crucial to systematically detail empirical evidence supporting the broad claims linking PA to environmental sustainability because these claims drive investments at multiple levels – from farmers buying tractors, to governments and supra-national organizations investing public money in PA projects (e.g. EU’s Internet of Food and Farm 2020). It is worth interrogating whether PA is the best way to spend money and other resources in our collective effort to address the global food system’s environmental challenges. PA is a newer strategy for agricultural reform, starting in the 1990s in industrialized contexts30. Meanwhile, there are historic methods that may be equally worthy of investment; locally adapted cropping strategies, including agroecological intercropping, cover cropping and extended crop rotations, for example, are well-studied techniques known to generate resilience in agricultural systems31,32,33,34,35.

Therefore, in this paper we ask: What empirical, field trial evidence exists to support the link between PA and environmental sustainability? To answer this question, we conducted a systematic review of English-language journal articles and full-length conference papers on PA and environmental sustainability, published between 2000 and 2022. We prioritized evidence from field trial experiments in the final coding but also collected modeling studies and review articles (See Methods for details). While broader definitions of “sustainability” exist, we aimed to be as precise as possible, focusing our search string on environmental benefits measured as reductions in resource use; reductions in water contamination; reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. In our assessment, this approach offers a quantifiable means to assess positive environmental impacts from PA.

The data collection and analysis focused on articles measuring PA technology in relation to fertilizer use, herbicide or pesticide use, water use, improved soil or water quality, or GHG emissions or fuel consumption (See Methods for details). In addition to our initial research aim of summarizing the evidence on PA adtopion’s environmental impact, our analysis uncovered a secondary phenomenon with serious implications: because the link between PA and environmental sustainability is so widely assumed, many academic authors make claims about PA’s environmental benefits for which they provide little or no support. Below, we first summarize the field trial evidence on PA and ecological gains before presenting an argument about the issue with assumptions and misleading claims in the academic literature.

Results

Limited Field Trial Evidence of Environmental Benefits

Our review yielded 82 publications that assess the environmental impacts of PA in relation to reduced fertilizer, herbicide, pesticide, water or fuel use; improved water or soil quality; or reduced GHG emissions. Of these 82 articles, 21 are modeling studies estimating environmental impacts of different possible uses of PA tools or farm simulations and 17 are review-style papers (e.g., systematic reviews, case studies), whereas 54 present field trial evidence associated to PA environmental impacts (either positive, negative, or neutral). These categories were not mutually exclusive; for example, within the 54 field trials, several studies with a field experiment are combined with a model36,37.

Of 54 field trial studies, 9 (17% of field trial studies) found no evidence of the environmental sustainability benefits, as conceptualized in our review. This included studies investigating reduced fertilizer use, reduced herbicide or pesticide use, reduced water use or contamination (e.g., runoff), and GHG emissions or fuel consumption. For example, Balaine et al. researched the use of milk meters for precision dairy operations, including the possible impacts on GHG emissions but “did not find a significant impact of milk recording on farm environmental sustainability, [which] suggests that productivity gains reached through milk recording may not be sufficient to dilute the GHG costs of animal maintenance”28. Bacenetti et al. tested variable rate fertilizer application for rice farming based on the “Pocket NNI” (smart app) and satellite data, finding that fertilizer use increased slightly with PA despite greater fertilizer efficiency38. Both these studies suggest that, in certain contexts, PA can increase negative environmental impacts. Another study concluded that one variable rate sprayer tool was “not suitable” for variable rate application of fertilizer after a 1-year trial on a citrus farm in the US39. Response times, or the ability to quickly change the rate of fertilizer application, are key for determining the efficacy of variable rate application technology and getting the right amount of fertilizer, at the right place, at the right time. This tool was unable to switch rates rapidly enough (2–5 s on average, when it would need to meet ≤ 1 second).

In the end, 45 articles present robust, field-trial evidence about the environmental benefits of PA technologies (See list of studies and benefits in Supplemental Information). This represents 55% of the articles included for full qualitative analysis and synthesis and 83% of field trial studies. There were 11 field trials on commercial farms in operation and 17 on purely experimental fields; the remaining 14 did not specify. Across the 45 studies, PA and reduction in fertilizer use was the most common benefit (22 studies). Some of these studies also presented evidence that targeted chemical applications result in reduced leaching of agrichemicals into nearby water systems, most likely because of a more efficient uptake of additional nutrients by targeted plants.

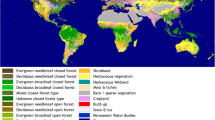

The 45 field trail studies demonstrating environmental benefits of PA span 13 countries, with more than one third based in the United States of America (See Fig. 1a). The countries indicate the location of the field trial experiment; the authors themselves come from a wider range of countries. Not all studies explicitly state the duration of their field trial. For those which do, the mean is 2.5 years. There are 15 studies whose experiment lasted one year or less (e.g., one field season from planting to harvest) and the longest study collected field trial data for seven years.

a World map with study sites (map generated with Excel and Bing; © Australian Bureau of Statistics, GeoNames, Microsoft, Open Places, OpenStreetMap, TomTom, and Zerin). b Publication years with the number of articles. Note: Search criteria included publications from 2000 to 2022. Four highly relevant articles published before 2000 (1987–1999) were included from other sources that were cited in the original dataset. c Publication outlet with the number of articles for outlets with more than one article. There were 16 other outlets with one only one article each.

The earliest study in our sample appeared in 1987, but two thirds (30) of the studies were published in 2010 or later (Fig. 1b). There were studies with evidence of reduced fertilizer use in each time period, with the most published between 2015 and 2019 (See Supplementary Fig. 1). Reduced pesticide and herbicide use were similarly consistent with a peak in the 2015–2019 period (Supplementary Fig. 1). The earliest study with evidence of reduced GHG emissions or fuel use was in 2012, and all evidence of environmental sustainability benefits for soil quality were published in 2020 or later (Supplementary Fig. 1). The studies are published in 31 different outlets, with the most articles published in the journal Precision Agriculture (Fig. 1c).

PA often involves the combination of multiple tools. For our analysis and data visualization, we classified each article by the primary or focus technology when there were multiple (See Table 1 and Supplemental Information). For example, the article “Sensor-based nitrogen applications out-performed producer-chosen rates for corn in on-farm demonstrations” by Scharf et al. presents evidence from 55 field trials of a variable rate fertilizer (N) application for corn based on reflectance sensors40. Because the authors report the reduction of fertilizer use as a function of the sensor-based management, we classified this as “sensors” in Table 1.

Environmental benefits of variable rate technologies

The field trial evidence most commonly demonstrates an environmental benefit from “variable rate” technologies (focus of 14 papers). Variable rate technologies allow farmers to treat different areas of their field with site-specific “rates” or “prescriptions” of agricultural inputs, using maps generated from data collection combined with computation. Most of the studies with benefits of variable rate show a reduction in fertilizer use (12 out of 14). For example, Harmel et al. tested variable rate application of fertilizer in corn production and found 4-7% reductions (on average) across the fields when compared with uniform application41. Interestingly, despite the reduction in fertilizer use, when the authors tested “runoff water quality” at the end of the two-year study, they found it to be “generally similar” to the baseline quality, measured before PA use. Similarly, Loures et al. found a 5% reduction in nitrogen fertilizer for corn production from the use of variable rate, which they report as both an economic and environmental gain14. A few studies, such as Colaço et al., found more sizable reduction in fertilizer use from variable rate application of compared to a uniform application; in this study on citrus orchards in Brazil, the authors demonstrate “up to 37.4% of K2O in field 1 and up to 39.6% of N in field 2, regarding the total amount applied in 5 years” 42.

Environmental benefits of “smart” sprayers

The second most common technology represented among the papers showing evidence of positive environmental gain from PA is automated or “smart” chemical sprayers (11 papers). Like variable rate technologies, “smart” sprayers adjust the application of inputs instead of a uniform treatment of the entire field or row. The most common application of this technology was for herbicide and pesticide use (11 papers). The average reduction in pesticides reported in these studies was quite high. For example, Chen and Zhu tested a “smart” sprayer on apple, peach, blueberry, raspberry fields over two years and found an average of 50% reduction in pesticide use compared to their control trial (non-PA use)43 Solanelles et al. tested a “smart” electronic control system for pesticide application with “liquid savings of 70%, 28% and 39% in comparison to a conventional application were recorded in the olive, pear and apple orchard, respectively” 44. Moltó et al. tested an automatic sprayer in an orange orchard using an electronic control system that adapts the dose of product to actual leaf mass; the field trial of their prototype saved pesticide application by 37% by volume45.

Environmental benefits of near and remote sensing

PA relies on data collection via a variety of sources, including soil and machine sensors, UAV/Drones, and satellites. Sensors were the next most common PA in the papers demonstrating environmental benefits (6 studies), followed closely by remote sensing tools, like GPS and GIS (5 studies). Fertilizer benefits were most common in this category of tools as well. Bazame et al. tested spectral sensors (GreenSeekerTM and SPAD 502) for grasslands over three grazing cycles over one summer46. The paper shows that sensors resulted in fertilizer “saving of 75 kg urea/ha/cycle”46. Cao et al. tested an active canopy sensor-based precision fertilizer (N) management strategy on winter oilseed rape and summer corn rotation; their four-year study showed that the sensing PA system reduced N fertilizer application by 36-60% and decreased total N losses by 57-81%47. Delgado and Bausch used GIS, GPS, and remote sensing-based fertilizer treatment on a corn farm in a two-year study which showed that by reducing “in season” N application by 136 kg N ha-, the residual soil NO3-N after harvest was significantly reduced when compared to control farmer practices. They write, “remote sensing ‘in season’ N management reduced total NO3-N leaching losses by 51 and 43 percent for the 2000 and 2001 growing seasons”48. The other common use of satellites for PA is GPS-guidance or steering for tractors. Based on self-reporting of 60 farmers in North Dakota, Basso et al. found that “thirty-four percent of the respondents used GPS guidance systems, resulting in savings of 6% of time and 6.32% of fuel. The results also showed that 27% of farms used autosteering systems and saved 5.75% of time and 5.33% fuel”. (2018, 4).

Technology and farm size and crop type

There appears to be an association between the environmental benefit and the specific PA technology used (Table 1 and Supplementary Information). In our dataset, reduced fertilizer use is most frequently achieved by variable rate technologies, while reduction in pesticides and herbicide is related to the use of “smart” sprayers. PA technologies are often designed to work in specific farm environments and to target different farm tasks or input applications. For example, Chen and Zhu’s “smart” sprayer is designed for liquid pesticide application on fruit planted in rows; it would not be suitable for a field of corn or wheat43. Other PA tools are more easily transferable, such as sensors (e.g., electromagnetic induction conductivity) for spatial variability in soil properties (e.g., moisture) and remote sensing data (e.g., Normalized Difference Vegetation Index or NDVI) for plant health and yield data (e.g., vegetation density), both used for cereal crops and fruit14,49.

Additionally, the crop type matters. The most common farm type represented is grains and oilseeds by far (26 of the 45 studies). The variable rate trials focus on grain and oilseeds, whereas trials for “smart” sprayers are situated in orchards or vineyards. The highest percentage reduction in pesticides application take place for orchards or tree fruits, namely citrus, apples, and olives.

Moreover, there is preliminary indication that farm size may matter for the feasibility of PA adoption. For example, Godwin et al. analyzed six years of remote sensing data to show that “real-time” digital farm management improved the efficiency of cereal production thus “reducing the nitrogen surplus by approximately one-third”49. However, these authors clearly state that the “[b]enefits from spatially variable application of nitrogen outweigh costs of the investment in precision farming systems for cereal farms greater than 75 ha”49. Borsato et al. also mention that they over-represent larger farms in their sample of 60 farms in Missouri evaluating environmental benefits of GPS-guided tractors50.

By contrast, Loures et al. conducted field trials on small farms (< 50 ha), suggesting that “an efficient combination of UAV/RPAS and NDVI enables important savings in productivity factors, promoting sustainable agriculture both in ecological and economic terms”14. We found one single study about PA and organic agriculture51.

Assumptions or misleading claims that PA equates to environmental gains

In addition to our initial research aims, our analysis uncovered a tendency for unsupported claims about PA’s environmental benefits. Asumptions of environmental gains occured in multiple adoption or “business case” papers. The adoption studies included in the corpus begin from the presupposition that PA increases environmental sustainability, and thus by measuring (e.g. via instruments) adoption of PA tools the authors assume de facto that positive environmental outcomes result. Aubert, Schroeder, and Grimaudo’s article from 2012, “IT as enabler of sustainable farming: an empirical analysis of farmers’ adoption decision of PA technology,” is a highly cited (905 times) and influential publication on the environmental sustainability benefits of PA17. The study uses survey data to estimate PA adoption using an original mathematical model. PA’s environmental sustainability benefits are asserted in the introduction of the paper, supported by a citation to a 2008 study modeling the potential benefits of variable rate technologies52.

Similarly, Loures et al. begin their feasibility study on the uptake and use of PA on “small farms” by asserting: “it is a fact that PA constitutes…a crucial farm management system, which…enables farmers to reduce the application of crucial elements like water and/or fertilizers”14. This claim is not supported, neither with direct evidence nor with citations to papers which themselves present evidence. A third example is Nicol and Nicol’s “Adoption of PA to reduce inputs, enhance sustainability and increase food production: a study of southern Alberta, Canada”53. This paper provides data on the adoption of PA in midwestern Canada, but it does not directly test how this adoption does or does not influence the environmental impacts. Though these studies do not measure PA impacts on the environment, they claim environmental sustainability benefits simply because the authors find increased adoption of PA. Said differenetly, these studies assume that adoption of PA leads inextricably to environmental gains.

Another category of paper presents either tenuous evidence or is actively misleading in the citational practices deployed. As an example, Lassoued et al. only presents evidence from “international biotechnology experts” who were surveyed on their perceptions regarding PA’s “potential benefit” for the environment54. As another example, Schimmelpfennig uses an extant dataset (U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Census of Agriculture) to correlate PA adoption with what the author terms “analogous practices”: care for soil health, nutrient control to avoid overapplications, monitoring of fields for pests to allow early interventions, between-season field operations planning, and long-term written plans55,56. Not only is the reporting potentially statistically spurious, upon close examination some of the findings appear to undermine the argument that PA leads to environmental sustainability.

A notable example of potentially misleading reporting on PA and environmental sustainability is the highly cited (906 times per Google Scholar) paper by Balafoutis and colleagues: “Precision agriculture technologies positively contributing to GHG emissions mitigation, farm productivity and economics”57. This paper discusses a summary of different technologies that might fall under the rubric of PA, from GPS-guidance and auto-steer to controlled traffic farming. Balafoutis et al. present some evidence of environmental benefits of PA by citing other studies, few of which give field-trial evidence. The language in the article itself is more tentative than the title from which one would conclude that there is a scientific consensus on PA and environmental sustainability. Yet in the paper, Balafoutis et al. write that “literature is limited on data regarding the effect of PA on climate change” and that “there is a necessity that more research should be carried out on quantifying the impact of PATs on GHG emissions reduction”57.

We also noticed that across the literature authors are making big claims about PA’s environmental sustainability benefits and not supporting these claims with citations. This practice often occurs in the introductory section of a scientific study. As example, Sariga et al. write that PA “reduces the environmental impacts in several ways including the reduced water usage or the less farm chemicals in water” and that PA is a method of farming resulting in “less environmental impacts and results to maximum production”58. There is no empirical evidence to support these claims in the article itself nor are these claims referenced (i.e. there is no supporting data coming from additional sources). Similarly, Yinyan et al. claim that PA will “improve the agroecological environment” without evidence59.

By highlighting these instances of assumptions or misleading claims that PA equates to environmental gains, we do not intend to vilify these authors. Instead, these observations highlight the ubiquity of the belief that PA is inextricably linked to environmental sustainability. It could be that citations or evidence are deemed unnecessary for something that is perceived to be common knowledge. However, based on the evidence reviewed in our study, we find that environmental sustainability is not inherent to the technology. Environmental benefits of PA are not guaranteed and depend on the context and application.

Discussion

In this paper, we reviewed the body of empirical evidence published in English-language journals connecting PA to environmental outcomes. Our review uncovered some evidence supporting the claim that PA leads to environmental sustainability. Much of the evidence linked PA to a reduction in agricultural inputs associated with envieronmental harms, such as fertilizer. In addition to our original research aim, we found that many academic authors appear to hold an assumption about the “inextricable link” between PA and environmental sustainability that is not fully tested nor supported by evidence. This finding is significant both for upholding rigor within the scientific community and for implementing more sustainable agricultural practices around the world.

Overall, we find a relatively low number of studies that rigorously examine on-the-ground environmental impacts through field trials: 54 articles over 22 years (with four earlier studies added for a total span of 35 years). These field trials also have relatively short duration (averaging 2.5 years), limiting their ability to assess long-term environmental impacts, whereas research on other topics have more long-term field trial, of 10, 40, or even 75 years60,61,62. While field trials are expensive and time-consuming, we contend that additional studies are essential to assessing environmental sustainability claims.

Agriculture, and the environments in which PA is practiced, are highly diverse. Yet existing studies are geographically limited, with no field trials found in Africa, nor any in a Latin American country other than Brazil. There are certainly uses of PA across countries in Africa63,64,65. In 2024, Marrakech hosted the third annual African Conference on PA in personal and virtually, with nine other in-person satellite gatherings across the continent. This is also a region about which there are big claims for the potential environmental sustainability and other benefits of PA3,66,67. While this discrepancy may be due to our focus on English-language publications and adoption rates of PA, certainly more research is necessary to understand environmental outcomes across a range of countries (or representation of existing research in peer reviewed journals).

PA represents a range of technologies with a variety of economic costs and social impacts; understanding the sustainability implications for each of these is important given the range in crop and farm types worldwide. While several studies assessed the environmental impacts of variable rate in grain farming, for instance, few researched use of PA for fruits, vegetables, or legumes. Further, there was only one study with organic farming practices51.

There were only two commercial farms under 55 ha with field trial evidence of environmental benefits, in addition to a few smaller experimental plots. Globally, 84 percent of farms have at most 2 hectares of agricultural land (< 5 acres); of these, 70 percent farm 1 hectare or less68. A significant portion of the world’s food comes from these operations. Small farms (≤ 2 ha) produce 35% of the world’s food on 12% of the world’s agricultural land68. Small farms are much more prevalent in low- and middle-income countries68. Across the globe, small farms are achieving higher yields, while protecting more crop diversity and non-crop biodiversity around their fields, relative to their size69,70. Smaller farms are more likely to grow crops for food, rather than for biofuels or other non-food commodities71. However, to achieve these outcomes, small farms are usually more labor intensive and less profitable than larger farms69,71. They are also less likely to benefit from technological innovation, like AI, not just because these tools are not designed for their conditions, like crop diversity, but also because they do not have access to the capital that is required to pay for the newest technologies. More research is needed to understand potential and observed environmental and other benefits of PA in these contexts.

There are many narratives and definitions of sustainability in food systems and sustainable agriculture72,73,74,75. Future studies could adopt a more expansive approach to defining sustainability and assessing environmental outcomes. The most common benefit of PA across the studies was reduction in fertilizer use. While we agree that reducing agri-chemical input use is important for environmental and human health, there are multiple aspects of environmental impacts and models for sustainability in agriculture. For example, the legal definition of sustainable agriculture at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) refers to:

an integrated system of plant and animal production practices having a site-specific application that will over the long-term: satisfy human food and fiber needs; enhance environmental quality and the natural resource base upon which the agriculture economy depends; make the most efficient use of nonrenewable resources and on-farm resources and integrate, where appropriate, natural biological cycles and controls; sustain the economic viability of farm operations; [and] enhance the quality of life for farmers and society as a whole76.

Other organizations have an even broader definition which includes environmental and social factors. For instance, Eco Canada states: “the goals of sustainable agriculture are; to help provide enough food for everyone, bring communities out of poverty and provide an enhanced quality of life for farming families, and utilize farming methods that promote soil health and reduce reliance on fossil fuels for environmental sustainability”77. There are a host of sustainability metrics which could be used to judge the environmental contributions of specific agricultural techniques, such as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, ecosystem services, or the principles of agroecology and food sovereignty32,78,79,80,81,82.

In fact, few of the articles we read were explicit about the working model of sustainability used as it related to the metrics of sustainability against which PA was evaluated. There are two exceptions. One is the article by Dicks et al., which mentions “sustainable intensification” in their policy analysis of food production practices in the UK, including PA83. They define sustainable intensification as increasing agricultural productivity while creating environmental and social benefits. The second is Schimmelpfennig’s report, which uses The American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers draft standard, titled “Framework for Sustainable Agriculture” (X629), to measure best management practices as well as key sustainability and productivity indicators55,56.

The consequences of not clearly defining and measuring sustainability impacts of PA across a range of geographies, technologies, and agricultural systems are significant. While we do find evidence that PA can deliver specific types of environmental benefits in certain circumstances, we caution against the generalized assumption that has long remained unchallenged across the science and practice. We wish to make clear that we are not arguing that PA ought be dismissed as a potentially beneficial set of technologies. There appears to be some evidence of economic benefits for farmers in terms of resource use efficiency (e.g., greater yield with the same amount of fertilizer application). Ultimately, we urge a broader and more thoughtful definition of sustainability be taken by the research community, with more attempts to measure it across various agricultural systems, to guide the judicious and effective adoption of particular technologies and practices that can improve environmental outcomes in agriculture. We also invite future work on environmental sustainability of PA to include other forms of evidence and ways of knowing, including farmer-centric on-farm experimentation and community-engaged research with farmers, farmworkers, and technology developers84,85,86.

Methods

Effective systematic reviews “collect, synthesize, appraise and summarize the relevant evidence” in line with a specific research question, using clear and reproducible methods87,88. We designed a systematic review of literature on PA and sustainability to answer the question: What empirical, field trial evidence exists to support the link between PA and environmental sustainability? To report on the method, we follow the guidance from the RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses (ROSES) for environmental research88,89. See Fig. 2.

Review scope and search criteria

To investigate the evidence of PA in the systematic review, we began by setting a sustainability framework to guide the search, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and analysis strategy. The specific search string used was: “PA” OR “Precision farming” AND ((reduction OR reduce*) W/4 (pesticide* OR herbicide* OR water OR greenhouse)). Based on feedback from a reviewer, we ran an additional search to include fertilizer (ferili*). We did not include “soil” in our search string but added the category inductively during the analysis because it was frequently mentioned. We use the search string for three databases: Scopus, Web of Science, and Green File. We added filters for language (English), source type (journal articles and conference proceedings), and publication year (2000-2022). After removing duplicates, there were 444 articles for initial screening.

Abstract Review

Each researcher reviewed the abstracts and results sections to determine whether the article should be included in the full text review. For inclusion in the full text review, the article had to be a peer reviewed journal article or published full-length conference paper; be available in English; be published between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2022; and present some evidence on sustainability in its results section – specifically, related to herbicide, pesticide, or fertilizer use; water use or water conservation; soil quality or conservation; or GHG emissions or fuel consumption.

If an abstract did not meet one or more of the eligibility criteria or was a duplicate, it was excluded. In a spreadsheet, we recorded who reviewed the reference, bibliographic information, whether the reference met each of the inclusion criteria, and additional notes where relevant.

Full-Text Review

All researchers then proceeded to review the full text of the remaining 191 articles, dividing coding evenly to produce a list of 70 references. Articles without evidence of sustainability in relation to the above identified inclusion criteria were excluded. We also excluded articles that were not peer reviewed journal articles or whose full text could not be accessed through the University of Ottawa library catalog.

We added 12 snowballed articles to the final dataset. Each researcher could add new articles to the dataset for screening that were relevant but that did not appear in the initial search. Most of the articles added at this stage were selected as citations within the reviewed articles. Four highly relevant articles published before 2000 were included from other sources through snowball sampling or investigation of studies cited in the articles in the review. These articles were published in 1987, 1996, 1997, and 1999. The total after the full-text review is 82.

We also recorded the type of evidence associated with environmental claims and PA as field-trial experiments on farms; modeling (especially predictions and projections); or “other.” Articles with empirical or modeling evidence associated with PA and environmental factors were included in the final stage of the analysis, regardless of whether they reported environmental sustainability benefits. For the exclusion criteria of “not focused on sustainability impacts of PA,” many of the excluded references mentioned environmental sustainability in the title, abstract, or text, but only tested the functionality or adoption of PA tools. These studies largely appeared in technical journals or in proceedings of agricultural or engineering conferences. One example of such a study is “A real-time weed mapping and precision herbicide spraying system for row crops” by Xu et al.90. In its introduction, the authors of this paper assert that precision spraying leads to more sustainable production and they support this assertion with a citation to Rocha et al.’s “Weed mapping using techniques of PA”91. However, the cited paper discusses the technical dimensions of a weed-mapping technology, rather than the environmental impacts from its use.

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis

Based on the information about the type of evidence, we decided to focus on field trial evidence. We noted all field-trial studies about or using PA tools with claims about environmental sustainability. Some of these studies did not have empirical findings to support an environmental sustainability benefit or found negative or neutral results. With this data, we conducted descriptive statistics and frequency counts for study details and benefits (See Table 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Fig. 1). The qualitative analysis built on these frequency counts and other qualitative indicators to characterize the available evidence.

In Table 2, we outline all the information we collected on the final set of references. Supplementary Table 3 provides a condensed version of the records for the 45 references with field-trial evidence of environmental benefits associated with PA. The Supplementary Data file includes the complete responses for all 82 references included after full-text review.

Validity and Limitations

To increase the validity and reliability of our results, we took several steps. Researchers met multiple times at each step of the review to deliberate on the decisions being made. We coded several articles contemporaneously to encourage inter-coder reliability. The articles included in all stages of the review were evenly randomly assigned to the four researchers. For the 82 studies included in final analysis, each reference was coded by at least two researchers to ensure nothing was missed. Where there were disagreements, the two researchers would meet to come to a consensus.

We also offer additional transparency and acknowledge limitations. The first point of discussion is search terms. We chose PA because it has been widely used since the late twentieth century and remains prevalent over our inclusion period26,30,92. PA also has a formal definition by the International Society of PA15, which is more consistent that the definition of other related terms like “smart farming,” “digital agriculture,” and “site-specific farming.” PA is a term that includes a wide variety of tools for farm management, from soil sensors to satellites. Rather than include specific technologies in the search string, we were curious to see which tools would come up most frequently under the rubric of PA through inductive analysis. We acknowledge that there may be additional studies which did not use the term PA but which give data on specific tools and their environmental efficacy.

The primary motivation for the systematic review was to assess the evidence to support the common claim that PA presents positive environmental impacts or sustainability benefits. Therefore, our search string imbedded a positive frame of reducing resource use and environmental impacts. We could have included additional terms to gather evidence of increased resource use and environmental harms (e.g., [increase OR increasing] W/ [fertili* OR pesticide* OR herbicide* OR water OR greenhouse]). However, our aim was not to capture the evidence of negative environmental outcomes with PA, but rather to test a widely held assertion that PA and sustainability are inextricably linked.

Another possible approach would be to add efficiency or “efficien*” to the search as this concept commonly appears alongside PA sustainability claims. In our view, however, efficiency per se is too vague a term. Moreover, the widely accepted understanding of agricultural efficiency is productivity combined with resource use. As we have demonstrated, academic work currently is biased toward a measurement of only one part of this matrix— productivity—wherein if a yield increases, PA is labeled sustainable. Thus, we chose to focus on the ecological impacts from PA measured as reduced resource use and/or impacts.

Next, the exclusion criteria greatly influence what literature is represented in the review. We only included English-language publications, thus favoring English-speaking authors and countries. There is potentially additional literature from non-English speaking authors. As well, there are likely studies published in the years since we initiated the project and began data collection, some of which may have evidence of environmental sustainability benefits.

Finally, there are other possible ways to report and measure environmental and agronomic systems not limited to field trial evidence. Our rationale is grounded in well-recognized value of on-farm and field trial agricultural research93,94,95,96,97. Across many of its research outputs, the United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization asserts that experimental trials are best for deriving statistically valid, unbiased comparisons directly within farmers’ environments97. While modeling can offer benefits, such as structural insights and greater scales, modeling requires empirical validation to ensure credibility98. Modeling is about predictions and estimations; whereas, the focus of our review is on that which can be observed and measured.

Data availability

Data is available in Excel file: Supplementary Data.

References

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, W. E. P. & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2024 – Financing to End Hunger, Food Insecurity and Malnutrition in All Its Forms. https://doi.org/10.4060/cd1254en (FAO, 2024).

World Food Prize Foundation. Laureate Letter: Hunger’s Tipping Point. World Food Prize https://www.worldfoodprize.org/index.cfm?nodeID=96854&audienceID=1 (World Food Prize, 2025).

WEF. Innovation with a Purpose: The Role of Technology Innovation in Accelerating Food Systems Transformation. (WEF, 2018).

Denning, G. Sustainable intensification of agriculture: the foundation for universal food security. npj Sustain. Agric. 3, 1–5 (2025).

Giovannucci, D. et al. Food and Agriculture: The Future of Sustainability. SSRN Elect. J. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2054838 (2012).

Pingali, P. & Raney, T. Asian agricultural development: from the green revolution to the gene revolution. in Reasserting the Rural Development Agenda (eds. Balisacan, A. M. & Fuwa, N.) 159–190 (2007).

Bronson, K. Responsible to whom? Seed innovations and the corporatization of agriculture. J. Responsible Innov. 2, 62–77 (2015).

Clapp, J. Titans of Industrial Agriculture: How a Few Giant Corporations Came to Dominate the Farm Sector and Why It Matters. (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2025).

Clapp, J. Explaining Growing Glyphosate Use: The Political Economy of Herbicide-Dependent Agriculture. Glob. Environ. Change 67, 1–11 (2021).

Pesticides in a Changing Environment: Impact, Assessment, and Remediation. (Elsevier, Oxford, 2023).

Fan, X. et al. Effects of substituting synthetic nitrogen with organic amendments on crop yield, net greenhouse gas emissions and carbon footprint: A global meta-analysis. Field Crops Res 301, 378–4290 (2023).

Menegat, S., Ledo, A. & Tirado, R. Greenhouse gas emissions from global production and use of nitrogen synthetic fertilisers in agriculture. Nautre: Scientific Reports 12, 14490 (2022).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.) 1–34 https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.001 (Geneva, 2023).

Loures, L. et al. Assessing the effectiveness of precision agriculture management systems in mediterranean small farms. Sustainability 12, 3765 (2020).

ISPA. Precision Ag Definition. International Society of Precision Agriculture (ISPA, 2024).

McBratney, A., Whelan, B., Ancev, T. & Bouma, J. Future directions of precision agriculture. Precis Agric 6, 7–23 (2005).

Aubert, B. A., Schroeder, A. & Grimaudo, J. IT as enabler of sustainable farming: an empirical analysis of farmers’ adoption decision of precision agriculture technology. Decis. Support Syst. 54, 510–520 (2012).

The Climate Corporation. John Deere and The Climate Corporation Expand Precision and Digital Agriculture Options for Farmers. Climate Fieldview https://climate.com/newsroom/john-deere-climate-corp-expand-precision-digital-ag-options/15 (2015).

Trimble. Top 3 Ways Farmers Win with Precision Ag Software. Trimble: Agriculture https://agriculture.trimble.com/blog/top-3-ways-farmers-win-with-farm-software/ (Trimble, 2018).

Echelon. Precision Farming Improves Input Use. Nutrien Ag Solutions https://echelonag.ca/what-we-do/.

Blue River Technology. See & Spray - Blue River Technology’s precision weed control machine [YouTube]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-YCa8RntsRE (2017).

FCC. Precision agriculture can improve resource use and your bottom line. Farm Credit Canada https://www.fcc-fac.ca/en/knowledge/precision-agriculture-improve-bottom-line.

Ulimwengu, J. M. & Kibonge, A. Climate-smart agriculture practices based on precision agriculture: the case of maize in western Congo. in A thriving agricultural sector in a changing climate: Meeting Malabo Declaration goals through climate-smart agriculture (eds De Pinto, A. & Ulimwengu, M.) 86–102 https://doi.org/10.2499/9780896292949_07 (International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, D.C., 2017).

Bongiovanni, R. & Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. Precision agriculture and sustainability. Precis. Agric. 5, 359–387 (2004).

Lindblom, J., Lundström, C., Ljung, M. & Jonsson, A. Promoting sustainable intensification in precision agriculture: review of decision support systems development and strategies. Precis. Agric. 18, 309–311 (2017).

Plant, R. E., Stuart Pettygrove, G. & Reinert, W. R. Precision agriculture can increase profits and limit environmental impacts. Calif. Agric. 54, 66–71 (2000).

Brown, R. M., Dillon, C. R., Schieffer, J. & Shockley, J. M. The carbon footprint and economic impact of precision agriculture technology on a corn and soybean farm. J. Environ. Econ. Policy 5, 335–348 (2016).

Balaine, L., Dillon, E. J., Läpple, D. & Lynch, J. Can technology help achieve sustainable intensification? Evidence from milk recording on Irish dairy farms. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104437. (2020)

Green, A. G. et al. A scoping review of the digital agricultural revolution and ecosystem services: implications for Canadian policy and research agendas. Facets 6, 1955–1985 (2021).

Mulla, D. & Khosla, R. Historical Evolution and Recent Advances in Precision Farming. in Soil-Specific Farming: Precision Agriculture (eds. R. Lal & B. A. Stewart) 1–36 (CRC Press, 2016).

IPES-FOOD. From Uniformity to Diversity: A Paradigm Shift from Industrial Agriculture to Diversified Agroecological Systems. www.ipes-food.org (2016).

Oteros-Rozas, E., Ravera, F. & García-Llorente, M. How does agroecology contribute to the transitions towards social-ecological sustainability? Sustainability 11, 4372 (2019).

Vigani, M., Fellmann, T., Capkovicova, A. P. & Ferrari, E. Harvesting resilience: adapting the EU agricultural system to global challenges. npj Sustainable Agriculture 2, 21 https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-024-00028-y (2024).

Mazzafera, P., Favarin, J. L. & Andrade, S. A. L. de. Editorial: intercropping systems in sustainable agriculture. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 5, 1–3 (2021).

Pavageau, C., Pondini, S. & Geck, M. Money Flows: What Is Holding Back Investment in Agroecological Research for Africa? www.biovision.chwww.ipes-food.org (2020).

González Perea, R. et al. Modelling impacts of precision irrigation on crop yield and in-field water management. Precis. Agric. 19, 497–512 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-017-9535-4 (2018).

El Chami, D., Knox, J. W., Daccache, A., Keith Weatherhead, E. & Chami, E. D. Assessing the financial and environmental impacts of precision irrigation in a humid climate. Horticult. Sci. 1, 43–52 (2019).

Bacenetti, J. et al. May smart technologies reduce the environmental impact of nitrogen fertilization? A case study for paddy rice. Sci. Total Environ. 715, 136956 (2020).

Schumann, A. W. et al. Variable rate granular fertilization of citrus groves: spreader performance with single-tree prescription zones. Appl Eng. Agric 22, 19–24 (2006).

Scharf, P. C. et al. Sensor-based nitrogen applications out-performed producer-chosen rates for corn in on-farm demonstrations. Agron. J. 103, 1683–1691 (2011).

Harmel, R. D., Kenimer, A. L., Searcy, S. W. & Torbert, H. A. Runoff water quality impact of variable rate sidedress nitrogen application. Precis Agric 5, 247–261 (2004).

Colaço, A. F., Pagliuca, L. G., Romanelli, T. L. & Molin, J. P. Economic viability, energy and nutrient balances of site-specific fertilisation for citrus. Biosyst. Eng. 200, 138–156 (2020).

Chen, L. & Zhu, H. Evaluation of Laser-Guided Intelligent Sprayer to Control Insects and Diseases in Ornamental Nurseries and Fruit Farms. in ASTM Special Technical Publication (ed. Elsik, C. M.) vol. S. T. P. 1627 1–10 (ASTM International, 2020).

Solanelles, F. et al. An electronic control system for pesticide application proportional to the canopy width of tree crops. Biosyst. Eng. 95, 473–481 (2006).

Moltó, E., Martín, B. & Gutiérrez, A. Pesticide loss reduction by automatic adaptation of spraying on globular trees. J. Agric. Eng. Res. 78, 35–41 (2001).

Bazame, H. C., Pinto, F. A. C., Queiroz, D. S., de Queiroz, D. M. & Althoff, D. Spectral sensors prove beneficial in determining nitrogen fertilizer needs of Urochloa brizantha cv. Xaraés grass in Brazil. Tropical Grassl.-Forrajes Tropicales 8, 60–71 (2020).

Cao, Q. et al. Improving nitrogen use efficiency with minimal environmental risks using an active canopy sensor in a wheat-maize cropping system. Field Crops Res. 214, 365–372 (2017).

Bausch, W. C. & Delgado, J. A. Ground-Based Sensing of Plant Nitrogen Status in Irrigated Corn to Improve Nitrogen Management. Digital Imaging Spectr. Tech.: Appl. Precis. Agricult. Crop Physiol. 66, 151–163 (2004).

Godwin, R. J., Wood, G. A., Taylor, J. C., Knight, S. M. & Welsh, J. P. Precision farming of cereal crops: a review of a six year experiment to develop management guidelines. Biosyst. Eng. 84, 375–391 (2003).

Borsato, E., Galindo, A., Tarolli, P., Sartori, L. & Marinello, F. Evaluation of the grey water footprint comparing the indirect effects of different agricultural practices. Sustainability 2018 10, 3992 (2018).

Diacono, M. et al. A combined approach of geostatistics and geographical clustering for delineating homogeneous zones in a durum wheat field in organic farming. NJAS: Wagening. J. Life Sci. 1, 47–57 (2013).

Du, Q., Chang, N. B., Yang, C. & Srilakshmi, K. R. Combination of multispectral remote sensing, variable rate technology and environmental modeling for citrus pest management. J. Environ. Manag. 86, 14–26 (2008).

Nicol, L. A. & Nicol, C. J. Adoption of precision agriculture to reduce inputs, enhance sustainabiltiy and increase food production: A study of Southern Alberta, Canada. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 217, 327–336 (2018).

Lassoued, R., Macall, D. M., Smyth, S. J., Phillips, P. W. B. & Hesseln, H. Expert insights on the impacts of, and potential for, agricultural big data. Sustainability 13, 1–18 (2021).

Schimmelpfennig, D. Farm Profits and Adoption of Precision Agriculture. [Economic Research Report: #217]. www.ers.usda.gov/publications/err-economic-research-report/err217 (2016).

Schimmelpfennig, D. Crop production costs, profits, and ecosystem stewardship with precision agriculture. J. Agric. Appl. Econ. 50, 81–103 (2018).

Balafoutis, A. et al. Precision agriculture technologies positively contributing to ghg emissions mitigation, farm productivity and economics. Sustainability 9, 1339 (2017).

Sariga, A., Jaiganesh, S., Vengattaraman, T. & Sujatha, P. An implementation of embedded web server in farming sector. In Proc. International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems, ICCES 2016, Coimbatore, India. https://doi.org/10.1109/CESYS.2016.7889866 (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, 2016).

Yinyan, S., Zhichao, H., Xiaochan, W., Odhiambo, M. O. & Weimin, D. Motion analysis and system response of fertilizer feed apparatus for paddy Variable-Rate fertilizer spreader. Comput Electron Agric 153, 239–247 (2018).

Pätzold, S., Ostermann, M., Heggemann, T. & Wehrle, R. Impact of potassium fertilisation on mobile proximal gamma-ray spectrometry: case study on a long-term field trial. Precis Agric 25, 532–542 (2024).

Jacquin, E. et al. Does fertilizer type drive soil and litter macroinvertebrate communities in a sugarcane agroecosystem? Evidence from a 10-year field trial. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2024.109431(2024).

Rodale Institute. Farming Systems Trial: 40-Year Report. (2021).

Nyamekye, A. B., Klerkx, L. & Dewulf, A. Responsibly Designing Digital Agriculture Services Under Uncertainty in the Global South: The case of Esoko-Ghana. In The Politics of Knowledge in Inclusive Development and Innovation (eds Ludwig, D., Boogaard, B., Macnaghten, P.) London, UK, 214–226 https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003112525-13 (Routledge, 2021).

Rezaei-Moghaddam, K. & Salehi, S. Agricultural specialists’ intention toward precision agriculture technologies: integrating innovation characteristics to technology acceptance model. Afr. J. Agric Res 5, 1191–1199 (2010).

Abdulai, A. R. A new green revolution (GR) or neoliberal entrenchment in agri-food systems? Exploring narratives around digital agriculture (DA), food systems, and development in Sub-Sahara Africa. J. Dev. Stud. 58, 1588–1604 (2022).

Bureau Veritas. Precision Farming in Africa. Bureau Veritas: Africa https://www.bureauveritas.africa/magazine/precision-farming-africa (2021).

AUDA. Bolstering Africa’s Precision Agriculture On Smallholder Farming | AUDA-NEPAD. African Union Development Agency https://www.nepad.org/blog/bolstering-africas-precision-agriculture-smallholder-farming (2021).

Lowder, S. K., Sánchez, M. V. & Bertini, R. Which farms feed the world and has farmland become more concentrated? World Dev. 142, 1–15 (2021).

Norboo, J. & Tsewang Dolma, M. Relationship between farm size and productivity. IOSR J. Humanities Soc. Sci. 28, 25 (2023).

Ricciardi, V., Mehrabi, Z., Wittman, H., James, D. & Ramankutty, N. Higher yields and more biodiversity on smaller farms. Nat. Sustain 4, 651–657 (2021).

Ritchie, H. Smallholders produce one-third of the world’s food, less than half of what many headlines claim. Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/smallholder-food-production (2021).

Bless, A., Davila, F. & Plant, R. A genealogy of sustainable agriculture narratives: implications for the transformative potential of regenerative agriculture. Agric Hum. Values 40, 1379–1397 (2023).

Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: concepts, principles and evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 363, 447–465 (2008).

Garnett, T. Sustainability Problems, Perspectives and Solutions. Conference on ‘Future food and health’ [Symposium I: Sustainability and food security]. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 73, 29–39 (2013).

Purvis, B., Mao, Y. & Robinson, D. Three pillars of sustainability: in search of conceptual origins. Sustain Sci. 14, 681–695 (2019).

USDA. Sustainable Agriculture. U.S. Department of Agriculture https://www.nal.usda.gov/farms-and-agricultural-production-systems/sustainable-agriculture (2024).

ECO Canada. What is sustainable agriculture? ECO Canada https://eco.ca/blog/what-is-sustainable-agriculture/ (ECO, 2024).

Salliou, N., Muradian, R. & Barnaud, C. Governance of ecosystem services in agroecology: when coordination is needed but difficult to achieve. Sustainability 11, 1158 (2019).

Maas, B., Fabian, Y., Kross, S. M. & Richter, A. Divergent farmer and scientist perceptions of agricultural biodiversity, ecosystem services and decision-making. Biol. Conserv 256, 109065 (2021).

Lajoie-O’Malley, A., Bronson, K., van der Burg, S. & Klerkx, L. The future(s) of digital agriculture and sustainable food systems: An analysis of high-level policy documents. Ecosyst. Serv. 45, 1–12 (2020).

FAO. World Livestock: Transforming the Livestock Sector through the Sustainable Development Goals. http://www.fao.org/3/CA1201EN/ca1201en.pdf (2018).

Nyéléni. The Digitalization of food. Nyéléni Newsletter - No 37 6 (2019).

Dicks, L. V. et al. What agricultural practices are most likely to deliver “sustainable intensification” in the UK? Food Energy Secur 8, e00148 (2019).

Pircher, T. et al. Farmer-centered and structural perspectives on innovation and scaling: a study on sustainable agriculture and nutrition in East Africa. J. Agric. Educ. Ext. 30, 137–158 (2024).

Bramley, R. G. V., Song, X., Colaço, A. F., Evans, K. J. & Cook, S. E. Did someone say “farmer-centric”? Digital tools for spatially distributed on-farm experimentation. Agron. Sustain Dev. 42, 1–11 (2022).

Fairbairn, M. et al. Digital agriculture will perpetuate injustice unless led from the grassroots. Nat. Food 6, 312–315 (2025).

Brignardello-Petersen, R., Santesso, N. & Guyatt, G. H. Systematic reviews of the literature: an introduction to current methods. Am. J. Epidemiol. 194, 536–542 (2024).

Haddaway, N. R., Macura, B., Whaley, P. & Pullin, A. S. ROSES Reporting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses: Pro forma, flow-diagram and descriptive summary of the plan and conduct of environmental systematic reviews and systematic maps. Environ. Evid. 7, 4–11 (2018).

ROSES. ROSES: RepOrting standards for Systematic Evidence Syntheses in environmental research. https://www.roses-reporting.com (2017).

Xu, Y., Gao, Z., Khot, L., Meng, X. & Zhang, Q. A real-time weed mapping and precision herbicide spraying system for row crops. Sensors 18, 4245 (2018).

Rocha, F. C. et al. Weed mapping using techniques of precision agriculture. Planta Daninha 33, 157–164 (2015).

Vullaganti, N. Precision agriculture technologies for soil site-specific nutrient management: a comprehensive review. Artif. Intell. Agriculture 15, 147–161 (2025).

Bullock, D. S., Mieno, T. & Hwang, J. The value of conducting on-farm field trials using precision agriculture technology: a theory and simulations. Precis Agric 21, 1027–1044 (2020).

Sichinga-Ligowe, I. et al. An introduction to conducting responsible and reproducible agricultural research. CAB Reviews. 19, https://doi.org/10.1079/cabireviews.2024.0058 (2024).

Cerf, M., Jeuffroy, M. H., Prost, L. & Meynard, J. M. Participatory design of agricultural decision support tools: taking account of the use situations. Agron. Sustain Dev. 32, 899–910 (2012).

Asopa, V. N. & Beye, G. Management of Agricultural Research: A Training Manual. [Module 2, Research Planning]. https://www.fao.org/4/w7502e/w7502e00.htm#Contents (1997).

Avila, M. Strategies for farming systems research. Food and Agriculture Organization: Open Knowledge https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/499edead-e9ee-4234-bac0-8e4b161d0ee4/content/x5548e0n.htm.

Nielsen, S. S. et al. Guidance on good practice in conducting scientific assessments in animal health using modelling. EFSA J. 20, e07346 (2022).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Indigenous Lands on which we conducted this research. S.L.R., R.D., E.C.O., and K.B. currently work or have worked at the University of Ottawa, which is located on the traditional and unceded territory of the Omamìwìnini Anishnàbeg (Algonquin) Nation. H.F. works at the University of Montana, which is on the territories of the Salish and Kalispel Peoples. We thank University of Ottawa undergraduate sociology student, Hunter Vernhout, and MA student, Aiden Bradley, for their help with some of the data collection and analysis. This study was funded by the University of Ottawa internal grant for supporting publications titled, “Always be Closing” (2022-2024). S.L.R.’s involvement was funded by a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellowship. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.B. conceptualized the study and led the research team. K.B., S.L.R., and H.F. collaborated on research design and methods. S.L.R., H.F., R.D. E.C.O., and K.B. all conducted data curation and analysis. K.B., S.L.R., and H.F. drafted and revised the manuscript text. S.L.R. prepared all figures and tables. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruder, SL., Faxon, H.O., Orzel, E.C. et al. Reviewing the evidence on precision agriculture and environmental sustainability. npj Sustain. Agric. 4, 9 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-026-00128-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44264-026-00128-x