Abstract

Background

This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to investigate the survival outcomes following cytoreductive surgery (CRS) in patients with primary stage IV endometrial cancer (EC).

Methods

We systematically searched the Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE/PubMed, and Web of Science for original studies reporting survival outcomes of primary stage IV EC after complete, optimal, and incomplete CRS. Pooled hazard ratios (HRs) for overall survival (OS) comparing optimal CRS with incomplete CRS were calculated using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 and the Q-test.

Results

Twelve studies, including 748 patients, were analysed. 187 patients underwent complete CRS, and 146 patients optimal CRS. Ten studies reported a significant OS benefit after complete (18–48 months) and optimal CRS (13–34 months) compared to incomplete CRS (7–19 months). A benefit was also observed in patients with serous EC or extra- abdominal metastasis. Meta-analysis showed improved OS after complete/optimal vs. incomplete CRS (HR = 0.38, 95% CI 0.21–0.69, p = 0.0016). Heterogeneity was substantial between studies (I2 = 76.7%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

Our study supports considering CRS in all patients with primary stage IV EC if complete resection is deemed feasible, while also emphasizing the importance of weighing the harms and benefits of this extensive treatment and adopting shared decision-making.

PROSPERO registration

CRD42022302968 on May 10th, 2022.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) stage IV endometrial cancer (EC) accounts for only 3% of all EC diagnoses and has a dismal prognosis with a five-year overall survival (OS) of 15–21% [1]. Currently, several systemic therapies have demonstrated improved survival outcomes in patients with stage IV EC [2, 3]. However, the role of surgery, particularly cytoreductive surgery (CRS), in the primary treatment of stage IV EC cancer remains a topic of debate. Several guidelines [4,5,6,7] recommend CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC if complete resection is deemed feasible, following the rationale of CRS for ovarian cancer [8,9,10,11,12]. However, these recommendations are based on several observational studies which should be interpreted cautiously due to the limited sample size, potential selection bias, and heterogeneity of patients included in the study [13,14,15,16,17,18,19]. Furthermore, the survival benefit of CRS in patients with EC is not as clear as in ovarian cancer where complete and optimal CRS give a substantial survival benefit compared to incomplete or no CRS [20, 21]. Given this, and the uncertain feasibility of achieving complete CRS, along with the potential complications of such extensive surgery, there is still reluctance to perform CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC. The low incidence of primary stage IV EC, along with its heterogeneous nature, presents a complex challenge for clinicians [15, 21]. The heterogeneity arises not only from patient-specific factors such as comorbidities and WHO performance status, but also from heterogeneity in the extensiveness of stage IV EC, including intra-abdominal and/or distant metastases. When extra-abdominal disease is present, there may be even more reservations about performing extensive intra-abdominal surgery.

Prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses have shown the potential benefit of complete CRS on OS in advanced stage EC, however these studies also included studies on recurrent EC, stage III EC or solely stage IVB [13, 22, 23].

The aim of this study is to obtain insight into the benefit of complete or optimal CRS compared to incomplete CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC, and summarize the evidence for future treatment recommendations. We conducted a systematic review to comprehensively evaluate the existing literature on the survival benefit of CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC specifically. Additionally, a meta-analysis was performed to estimate the pooled effect of completeness of CRS compared to incomplete CRS on OS in women with primary stage IV EC.

Methods

This study was designed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis guidelines [24] and registered at PROSPERO prior to abstract screening (registration number CRD42022302968).

Literature search

A systematic literature search was performed in October 2022 in the Cochrane Library, Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, and Web of Science using a search strategy including terms representing ‘endometrial cancer’, ‘cytoreductive surgery’, and ‘survival’. A detailed search is outlined in Appendix A.

Eligibility criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, original studies had to enrol at least ten patients with primary stage IV EC who underwent CRS. These studies were required to report data on progression-free survival (PFS) and/or OS stratified by the extent of cytoreduction, which is complete (no residual disease), optimal (residual disease ≤ 1 cm) or incomplete (gross residual disease > 1 cm). If studies included patients with other stages of EC or recurrent EC, they were considered if survival data for primary stage IV patients were reported separately. Conference abstracts, case reports, review articles, meta-analyses, editorials, letters to the editor, and guidelines were excluded, as were studies on uterine sarcomas or those that involved HIPEC.

Study selection

The eligibility of all studies identified through the systematic search was evaluated by at least two of three reviewers (JM, EP, and LN) independently. EndNote reference manager was utilized for the initial screening. The screening was based on the article title and abstract, and those selected underwent a full-text review to determine if they met the inclusion criteria. Throughout the selection process, the independent findings were compared, and any discrepancies were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached.

Data extraction

Data was extracted and recorded by EP, LN and JM in a database with predefined variables. Extracted variables included median age, performance status, histological diagnosis, treatment, number of patients who received CRS, outcome of CRS, definitions of PFS and OS and the median PFS and OS, Kaplan-Meier estimates, hazard ratios (HR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and p-values.

Assessment of risk of bias

A modified Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of cohort studies was utilized to assess the quality of the included studies [25]. The scale was adjusted for application in our study with patients with complete/optimal CRS as the exposed cohort and incomplete CRS as the non-exposed cohort. Adequate follow-up time was set at a median follow up of at least 18 months (see Appendix B).

Data synthesis

All studies that were included in the systematic review were reviewed for eligibility for pooling in the meta-analysis by EP and NH. The objective of the meta-analysis was to estimate a pooled HR for PFS and/or OS by completeness of CRS. Studies were eligible for the meta-analysis if PFS and/or OS was compared between patients with a complete, optimal or incomplete CRS. If the HR and 95%CI were reported in the article, direct calculation of the natural logarithm of HR and its variance were performed (Appendix C). If not, imputation according to the methodology of Tierney et al. [26] was performed using other data provided in the article (Appendix D). For the meta-analysis, pooled estimates of the HR were calculated using random-effects models with the DerSimonian-Laird estimator for the amount of heterogeneity. Each study contributed according to its sample size using inverse variance weights. Statistical significance was pre-defined as a (two-sided) p <0.05. Heterogeneity in effect size between studies was assessed using the I2 and the Q-test. Statistical significance of heterogeneity was defined as I2>50% combined with a Q-test p-value of <0.05. Analyses were performed in R version 3.6.1 (http://www.r-project. org/) using the metafor package (https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metafor/index.html).

Results

Study selection and quality assessment

A total of 812 unique studies were found and screened for eligibility. 759 studies were excluded based on title and abstract screening for various reasons, including eligibility of the study population (such as no primary stage IV EC or other tumour types), no CRS, or case report, or no original study. For 52 studies, the full-text were evaluated, which led to the exclusion of another 40 studies. Out of 40 studies, 23 did not report data on patients with primary stage IV EC at all, or the data were not reported separately for the included subgroup of patients with primary stage IV EC. The remaining 17 studies that were excluded did not report survival outcomes by outcome of CRS. This resulted in the inclusion of 12 studies for the systematic review [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38].

Of these 12 included studies for the systematic review, two studies could not be included in the meta-analysis because the available data did not provide enough information for a pooled analysis [30, 37]. The remaining ten studies were evaluated for the meta-analysis [27,28,29, 31,32,33,34,35,36, 38]. As most studies only compared survival outcomes between the combined subgroup of complete and optimal CRS vs. incomplete CRS, a meta-analysis comparing complete CRS with either optimal or incomplete CRS was not feasible. The study of Shih et al. [36] had to be excluded as the authors compared the survival outcomes of complete CRS vs. optimal CRS vs. incomplete CRS. Hence, nine studies were pooled in the meta-analysis. As only two of these nine studies reported data on PFS [33, 38], we decided not to pool the data on PFS. An overview of the selection process is described in Fig. 1. The quality of the included studies was high in general with almost all studies scoring seven or eight out of eight points (see Appendix B).

Study and patient characteristics

The 12 studies that were included in the systematic review contained data on 768 patients with primary stage IV EC, of whom 748 (97%) underwent CRS. An overview of the study characteristics is shown in Table 1. The studies were published between 1997 and 2022, were all retrospective, and mostly single-centre studies. Besides the study by Eto et al. [31] which included 248 patients, most studies had included a small number of patients (range 31–68 patients). The majority of the included patients were postmenopausal. Four studies reported the pre-operative WHO performance status of patients (total of 386 patients) [29, 31, 37, 38], which was good in the majority of patients in studies (WHO 0–1, n = 351, 91% of 386 patients). Seven [27,28,29,30,31, 37, 38] of the 12 studies also included patients with extra-abdominal disease (n = 195), but the majority of the patients had intra-abdominal metastases only. If mentioned, the extra-abdominal metastases were mostly pulmonary metastases (n = 85 in seven studies), pleural effusion (n = 16), liver metastasis (n = 25), or inguinal, supraclavicular or mediastinal lymph nodes (n = 60). Ueda et al. [38] separately reported the outcomes of patients with intra-abdominal metastases only (n = 15) and patients with extra-abdominal metastases (n = 15). The most common histological subtype was endometroid EC (n = 339, 44%) and serous EC (n = 326, 42%). None of the studies specified if the stage IV diagnosis was made before or after surgery. Complete CRS was specifically defined by three studies as no visible disease [32, 33, 36]. Optimal CRS was defined as a reduction of the tumour mass to ≤1 cm in ten studies [27,28,29, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37], and as reduction to ≤2 cm in two studies [30, 38]. Definitions of survival were ‘from date of diagnosis’, or ‘date of surgery’ [29,30,31,32,33, 35,36,37] until ‘clinical/radiological recurrence’ (PFS) or ‘death’ or ‘last contact’ (OS). Four studies did not report a definition of survival [27, 28, 34, 38].

Treatment

A total of 748 patients (97% of the study population) underwent CRS. In seven studies (549 patients) the outcomes of CRS were reported separately for complete, optimal, or incomplete CRS [27,28,29, 31,32,33, 36], which were 187 (34.1%), 146 (26.6%) and 216 (39.3%) patients respectively. In the remaining five studies (including 199 patients) [30, 34, 35, 37, 38] completeness of CRS was reported for complete and optimal together, being 105 patients (52.8%).

To achieve complete or optimal CRS, additional surgical procedures were performed in a total of 123 patients (21% of the total study population of these studies, n = 596) besides the standard procedure of hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and omentectomy. These additional surgical procedures were described in nine studies, and included bowel resections (n = 61), appendectomies (n = 47), splenectomies (n = 2), liver resections (n = 3), lung resections (n = 2), and ureter/bladder resections (n = 3)[28,29,30,31, 33,34,35, 37, 38]. No details were provided on the placement of a stoma.

The surgical treatment of the extra-abdominal metastases was described in three of the seven studies that specifically mentioned patients with extra-abdominal disease. In the study by Ayhan et al. [27] in three of the six patients the extra-abdominal metastases (lung, inguinal lymph node and supraclavicular lymph node) were completely resected. In the study of Eto et al. [31] a total of 93 patients (38% of the study population) had extra-abdominal disease. In 14 of them surgical removal was attempted, which was successful in 13 patients. Another study that reported on the treatment of extra-abdominal disease was the study by Ueda et al. [38] In this study 18 patients out of a total of 33 patients had one or more extra-abdominal metastases, located at the lungs (n = 8), liver (n = 7), pleural effusion (n = 5), supraclavicular lymph nodes (n = 5) and inguinal lymph nodes (n = 2). Surgical removal of these metastases was performed for the liver metastases (n = 2), supraclavicular lymph node metastases (n = 2), lung metastases (n = 1), and inguinal lymph node metastases (n = 1).

Peri- and postoperative complications were reported in only five of 12 studies [27,28,29, 31, 34]. Four of these studies provided the number of patients experiencing any peri-and postoperative complications [27,28,29,30, 34], with a total of 46 out of 182 patients having complications (25.3%). The most comprehensive descriptions were reported by Ayhan et al. [27], Bristow et al. [28], and Moller et al. [34], with complication rates of 40.5% (n = 15), 51.6% (n = 16), and 23% (n = 12) respectively. The latter study revealed that the rate of complications did not differ between patients who underwent complete/optimal or incomplete CRS (p = 0.33). Among the reported complications, two were fatal (0.5% of 430 patients in total), one patient died due to pulmonary embolism and the other due to small bowel obstruction followed by sepsis [27, 28]. The five studies collectively documented 21 patients with major or severe complications (5% of 430 patients), including: myocardial infarction, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, anastomotic gastrointestinal leak, cerebrovascular accident, thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism. Fourteen patients experienced mild complications according to the authors (3% of 430 patients).

The majority of patients (n = 575, 75% of total study population) received chemotherapy. In two studies it was separately reported that four patients had received neo-adjuvant chemotherapy [32, 37], in the remaining studies neo-adjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy was not separately mentioned. The adjuvant chemotherapy treatment regimens differed among studies. Platinum-based chemotherapy (carboplatin or cisplatin) was the only agent or combined with paclitaxel. Other frequently administered chemotherapy agents were doxorubicin) or cyclophosphamide. Less common chemotherapy regimens included agents such as docetaxel, epirubicine, ifosfamide, irinotecan, vinorelbine, and 5-fluorouracil.

Adjuvant radiotherapy was given in almost all studies to a small proportion of the patients (n = 155, 20%), and consisted of external beam radiotherapy in the majority of the patients or vaginal brachytherapy or both [27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34, 36, 37]. In four studies, a total of 66 patients (9%) received hormonal treatment as adjuvant therapy [30, 34, 36,37,38].

Survival

All included studies reported on OS data and ten studies found a significant advantage of complete and/or optimal CRS compared to incomplete CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC (Table 2) [27,28,29,30,31,32,33, 35, 36, 38]. Only three studies reported the OS separately for complete, optimal, and incomplete CRS [27, 31, 33]. In these three studies, OS was longer for patients who had complete CRS (48, 48, and 18 months) compared to patients with incomplete CRS (10, 14, and 7 months). Patients with optimal CRS had intermediate OS times which were closer to those of incomplete CRS in two out of three of the studies (13, 23, and 17 months). Ayhan et al. [27] and McEachron et al. [33] provided p-values that compared complete vs. optimal CRS. In the first study, the p-value was 0.001 (OS of 48 months after complete CRS and 13 months after optimal CRS), whilst for the study of McEachron et al. [33] the p-value was 0.67 (OS of 18 months after complete CRS and 17 months after optimal CRS). Both of these studies found a significant benefit of complete/optimal CRS vs. incomplete CRS (both <0.001). Shih et al. [36] reported a significant difference (p = <0.001) in OS among patients who underwent complete CRS (42 months) vs. optimal/incomplete CRS (19 months) vs. irresectable (2.2 months). In seven studies, the results of patients with complete and optimal CRS were combined and compared to incomplete CRS [28,29,30, 32, 34, 35, 38]. The complete/optimal CRS patients had an OS that ranged from 15 to 57 months, which was significantly better than after incomplete CRS (6–13 months), in all but two studies [34, 37].

Five studies [28, 32,33,34,35] focused solely on patients with serous EC. Despite that OS seemed substantially shorter in these studies, four out of five studies demonstrated a significant OS benefit of complete/optimal CRS compared to incomplete CRS [28, 32, 33, 35]. McEachron et al. [33] reported an OS of 18 months for patients who had complete CRS, 17 months for optimal CRS, and 7 months for patients after incomplete CRS (p < 0.001). In the remaining three studies [28, 32, 35], results of patients with complete/optimal CRS showed an OS ranging from 15 to 31 months, compared to eight to 13 months after incomplete CRS.

Two studies reported on OS after CRS in patients with extra-abdominal metastases [31, 38]. Both showed a benefit of complete/optimal CRS regardless of their extra-abdominal metastases. In the study of Ueda et al. [38], patients with extra-abdominal metastases had an OS of 57 months after complete/optimal CRS (residual disease ≤ 2 cm), compared to six months after incomplete CRS (p = 0.0016). Similarly, Eto et al. [31] reported an OS after a complete CRS of 58 months vs. 11 months after optimal and incomplete CRS (p = 0.0012).

Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis included nine eligible studies that all reported OS data on primary stage IV EC patients who underwent complete/optimal CRS vs. incomplete CRS [27,28,29, 31,32,33,34,35, 38]. Ueda et al. [38] provided the data on the OS for patients with intra-abdominal metastasis only and patients with additional extra-abdominal metastasis separately. Therefore, the data from this study were included in the meta-analysis as two separate cohorts of one study. Five studies reported a HR with 95%CI of OS for complete/optimal vs. incomplete CRS [28, 31,32,33, 38], while for the remaining four studies [27, 29, 34, 35] the HR was imputed by the method outlined by Tierney et al. [26] (Appendix C).

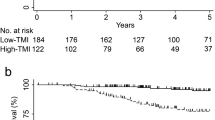

The meta-analysis showed that complete/optimal CRS was associated with a significant better OS, compared to incomplete CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC (pooled HR 0.38, 95% CI 0.21–0.69) (Fig. 2). Among the studies included in our meta-analysis, the study by Eto et al. [31] carries the most weight in the meta-analysis because it has the largest population. This study, along with the study conducted by Moller et al. [34] showed the least favourable effect of complete/optimal CRS. Both patient groups in the study conducted by Ueda et al. [38] (intra-abdominal disease only (n = 15), and extra-abdominal disease (n = 15)) had a significant benefit of complete/optimal CRS.

Sensitivity analysis showed that the estimate of the pooled HR is robust and not disproportionately influenced by any individual study (see Appendix D). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2 of 76.7%, Q test p < 0.0001, Fig. 2) and none of the studies has used propensity score matching. The funnel plot (Fig. 3) shows substantial asymmetry favouring positive studies, which indicates publication bias towards a beneficial effect of complete/optimal CRS, compared to incomplete CRS. This was confirmed by the test for asymmetry (p = 0.0014).

The studies are represented by dots. The dashed vertical line represents the pooled HR. Substantial asymmetry of the studies compared to the line of the pooled estimate is observed. The test for funnel plot asymmetry is significant and confirms the presence of publication bias. Definition of abbreviation: CRS cytoreductive surgery.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the survival benefit of CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC. Of the 12 included studies, ten showed a favourable effect on OS of complete/optimal CRS compared to incomplete CRS. Meta-analysis showed a pooled HR of 0.38 (95% CI 0.28–0.69, p = 0.0016) in favour of complete/optimal CRS. Studies that looked into the effect of complete CRS compared to optimal and/or incomplete CRS reported an OS of more than 40 months after complete CRS compared to 13–23 months after optimal and 7–14 months after incomplete CRS. Our results highlight the value of complete/optimal CRS, applying the same paradigm of high-stage ovarian cancer for EC [8]. Current guidelines recommend CRS in women with advanced EC if complete resection is deemed feasible [5, 39, 40]. However, there is still reluctance to perform surgery in stage IV EC among clinicians, due to the challenges of CRS in patients with stage IV EC which are also observed in our study.

Primary stage IV EC comprises a heterogeneous patient population due to several factors, firstly due to presence of extra-abdominal metastases in some patients with stage IV EC. In our review, the majority of the patients had intra-abdominal metastasis only. The significance of differentiation between pelvic, abdominal, and extra-abdominal metastases is demonstrated in the study by Height et al. [41] Applying the FIGO 2023 stage for EC [42], which classifies pelvic metastases as stage III and extra-abdominal metastases as stage IVC, their findings revealed a significant prolonged OS among patients with stage III under the updated classification, while these patients were classified as stage IV according to FIGO 2009 staging. Current guidelines do not specify whether CRS should be attempted in the presence of extra-abdominal disease. Within our review, three studies that included patients with extra-abdominal disease documented the surgical removal of metastases located in the lungs, liver, supraclavicular and inguinal lymph nodes, umbilicus/skin, and breast. Surgical removal of bone and brain metastases was not performed. Additionally, in one study (Eto et al. [31]) radiotherapy was administered for extra-abdominal metastases. The majority of this cohort with extra-abdominal metastases had metastasis localized in a single anatomical region. Patients who underwent complete/optimal CRS had a significant longer OS, regardless of the presence of extra-abdominal metastases. Guo et al. [43] demonstrated a survival benefit after surgical removal of lung, bone or multiple organ metastases. Therefore we would argue that complete/optimal CRS offers a benefit even in the presence of extra-abdominal disease, especially when it is localized at a single anatomical region other than the brain.

Additionally, the histologic subtype of EC introduces heterogeneity in patients with primary stage IV EC. Serous EC, characterized by its high-grade nature and aggressiveness, is more frequently detected in advanced stages of the disease [44, 45]. It has been suggested that less aggressive tumours are better suited for complete resection, implying that observed survival benefit may also be attributed to the histological characteristics of the tumour rather than solely the surgical intervention itself [27, 30, 38]. In our review five studies included patients with serous EC only, and four reported a significant advantage in OS after complete or optimal CRS compared to incomplete CRS. These findings demonstrate that CRS can be advantageous even in the more aggressive histological subtype serous stage IV EC patients.

Lastly, determining the independent impact of complete/optimal CRS versus incomplete CRS is challenging due to patient-related factors that directly and indirectly affect survival, resulting in a risk of confounding by indication. Patients with EC typically exhibit characteristics such as advanced age, frailty, and potential comorbidities. These patient-related factors contribute to potential prolonged post-surgical recovery and the risk on peri- and postoperative complications and mortality [33]. Multivariable analyses showed that complete/optimal CRS significantly improved survival, even after adjusting for factors such as age and performance status. Addressing the peri- and postoperative complications, only a few studies provided information on this. When reported, a notable percentage of patients experienced complications (23–51.6%). Objective tools such as frailty assessment questionnaires like the G8 questionnaire [46] and WHO performance status can help predict post-surgical morbidity rates. In conclusion, treatment of frail women with primary stage IV EC poses additional challenges, requiring a delicate balance between the risk of complications and the potential survival benefits, where the focus should not be solely on age but also on physical health and patients’ preferences.

In our review, we observed variations in the definition of optimal CRS among the studies. While most studies defined optimal CRS as ≤1 cm residual disease, some studies used a less strict criterion of ≤2 cm residual disease. Despite the difference in cut-off values, both optimal CRS definitions were associated with improved survival outcomes. In our study cohort, a significant proportion (40 to 47%) still had residual macroscopic disease exceeding one or two cm following surgery. Based on our findings, we recommend a thorough pre-operative assessment to determine the feasibility of complete CRS and only perform surgery if complete CRS appears achievable. In patients in whom complete CRS is not feasible during surgery, efforts should be made to achieve optimal CRS as residual disease ≤1 cm is more effectively managed through adjuvant radiotherapy or systemic therapy.

This study and three previously published systematic reviews and meta-analyses [13, 22, 23] have investigated the benefit of complete and/or optimal CRS in patients with advanced stage EC. The most recent study, a systematic review by Capozzi et al. [23] has investigated the optimal management for stage IVB EC and stated that determining the optimal treatment for these patients remains complex due to the lack of comprehensive evidence. The authors, similar to our perspective, conclude after the systematic review that optimal CRS remains crucial, however this effect is not quantified in a meta-analysis. The systematic review and meta-analysis by Albright et al. [22], included studies on patients with both stage III and stage IV EC. Thirty-four studies were selected, of these, 11 were also included in our meta-analysis. The estimated effect of complete/optimal CRS was similar to our study, but the pooled HR was calculated by dividing the median survival in the two groups, rather than taking the whole survival curves into account as recommended [26]. However, the results presented in the meta-analysis of Albright et al. [18] cannot be extrapolated to patients with primary stage IV EC, because patients with stage III EC are more often treated with emphasis on curative treatment. In 2010, Barlin et al. [13] conducted a meta-analysis to determine prognostic factors for OS in patients with stage III and IV and recurrent EC. They found that complete and optimal CRS was significantly associated with a longer OS. These abovementioned results are in line with our meta-analysis.

Future studies should prospectively investigate the effect of CRS in patients with primary stage IV EC on survival, morbidity and quality of life. In these studies details on pre-operative imaging, surgical decision-making, and the extent of surgery should be recorded. Moreover, the heterogeneity resulting from the intra- or extra-abdominal localization of metastases can be more effectively classified through the incorporation of the FIGO 2023 staging for endometrial cancer [42]. With this staging the role of the molecular classification [47], both on prognostic impact and prediction for completeness of CRS is also incorporated. In stage I-III EC, the different molecular EC classes are known to have a distinct prognosis and respond differently to adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy [48,49,50]. For stage IV EC, molecular classification did not show prognostic value in a retrospective study [51]. Given the rarity and poor prognosis of this patient group, a multi-centre, international, prospective study is needed to investigate the impact of molecular classification on prognosis in stage IV EC.

To our knowledge, this study stands out as the sole systematic review and meta-analysis that specifically focuses on CRS in patients diagnosed with primary stage IV EC. We conducted a comprehensive and systematic search across five databases to ensure the inclusion of all relevant studies for our aim. There was optimal use of the available data by advanced imputation techniques and performed state-of-the-art statistical analyses. However, due to limitations in the available data from the included studies, we could only investigate the effect of complete/optimal CRS versus incomplete CRS.

The quality of every meta-analysis depends on the quality of the original studies that are pooled. Here, only relatively small, retrospective studies were available, which are hampered by selection bias, registration bias, and confounding by indication. In addition, our analysis showed that there is significant publication bias, in favour of studies showing a positive impact of complete/optimal CRS on survival. Hence, the estimated benefit of complete/optimal CRS might be overestimated. Another limitation is the substantial heterogeneity between the included studies. Differences in sample size, treatment approaches, the extent and aggressiveness of the disease before surgery, and potential differences in fatal pre/post-operative complications between studies likely contribute to the high heterogeneity. This causes additional uncertainty in the pooled estimate of the HR that is not fully addressed by the 95% CI.

Conclusion

Primary stage IV EC is a rare and heterogeneous disease which is associated with a dismal prognosis. This systematic review and meta-analysis provides an overview of current evidence on the value of CRS and shows a benefit in OS in patients who underwent complete/optimal CRS, with a superior effect of complete compared to optimal CRS. This benefit seems also present in patients with extra-abdominal disease, and irrespective of the histological subtype of EC. These findings support the consideration of CRS in all patients with primary stage IV EC if achieving complete resection is deemed feasible. It is, however, crucial to take the harms and benefits of this extensive treatment into account and to adopt shared-decision making in these patients.

Data availability

Research data are stored in an institutional repository and can be shared upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Creasman WT, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P, Quinn MA, Beller U, Benedet JL. et al. Carcinoma of the corpus uteri. FIGO 26th Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;95:S105–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7292(06)60031-3.

Mirza MR, Chase DM, Slomovitz BM, dePont Christensen R, Novak Z, Black D, et al. Dostarlimab for primary advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer. N Engl J Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2216334.

Galaal K, Al Moundhri M, Bryant A, Lopes AD, Lawrie TA. Adjuvant chemotherapy for advanced endometrial cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2014:CD010681.

Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, Barber E, Bradley K, Brooks R, et al. Uterine neoplasms, version 2.2024, March 6, 2024; page 14, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024.

Concin N, Matias-Guiu X, Vergote I, Cibula D, Mirza MR, Marnitz S, et al. ESGO/ESTRO/ESP guidelines for the management of patients with endometrial carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2021;31:12–39. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2020-002230.

PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board. PDQ Endometrial Cancer Treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Updated <02/08/2024>. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/types/uterine/hp/endometrial-treatment-pdq.

Restaino S, Paglietti C, Arcieri M, Biasioli A, Della Martina M, Mariuzzi L, et al. Management of patients diagnosed with endometrial cancer: comparison of guidelines. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15041091.

Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, Kristensen GB, Ehlen T, Johnson N. et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943–53. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0908806.

van der Burg ME, van Lent M, Buyse M, Kobierska A, Colombo N, Favalli G. et al. The effect of debulking surgery after induction chemotherapy on the prognosis in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecological Cancer Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:629–34. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199503093321002.

Bryant A, Hiu S, Kunonga PT, Gajjar K, Craig D, Vale L. et al. Impact of residual disease as a prognostic factor for survival in women with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer after primary surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.2022;9:CD015048. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.

Chang SJ, Hodeib M, Chang J, Bristow RE. Survival impact of complete cytoreduction to no gross residual disease for advanced-stage ovarian cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;130:493–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.05.040.

Ozols RF, Bundy BN, Greer BE, Fowler JM, Clarke-Pearson D, Burger RA, et al. Phase III trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel compared with cisplatin and paclitaxel in patients with optimally resected stage III ovarian cancer: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3194–200. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.02.153.

Barlin JN, Puri I, Bristow RE. Cytoreductive surgery for advanced or recurrent endometrial cancer: a meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;118:14–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.04.005.

Cirik DA, Karalok A, Ureyen I, Tasci T, Koc S, Turan T, et al. Stage IVB endometrial cancer confined to the abdomen: is chemotherapy superior to radiotherapy? Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2016;37:226–31.

Lambrou NC, Gomez-Marin O, Mirhashemi R, Beach H, Salom E, Almeida-Parra Z, et al. Optimal surgical cytoreduction in patients with Stage III and Stage IV endometrial carcinoma: a study of morbidity and survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:653–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.015.

Rajkumar S, Nath R, Lane G, Mehra G, Begum S, Sayasneh A. Advanced stage (IIIC/IV) endometrial cancer: Role of cytoreduction and determinants of survival. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2019;234:26–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.11.029.

Schmidt AM, Imesch P, Fink D, Egger H. Pelvic Exenterations for Advanced and Recurrent Endometrial Cancer: Clinical Outcomes of 40 Patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26:716–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/IGC.0000000000000678.

Solmaz U, Mat E, Dereli ML, Turan V, Ekin A, Tosun G, et al. Stage-III and -IV endometrial cancer: A single oncology centre review of 104 cases. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;36:81–6. https://doi.org/10.3109/01443615.2015.1041890.

Vitale SG, Valenti G, Gulino FA, Cignini P, Biondi A. Surgical treatment of high stage endometrial cancer: current perspectives. Updates Surg. 2016;68:149–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-015-0340-1.

Landrum LM, Moore KN, Myers TK, Lanneau GS Jr, McMeekin DS, Walker JL, et al. Stage IVB endometrial cancer: does applying an ovarian cancer treatment paradigm result in similar outcomes? A case-control analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:337–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.10.009.

du Bois A, Reuss A, Pujade-Lauraine E, Harter P, Ray-Coquard I, Pfisterer J. Role of surgical outcome as prognostic factor in advanced epithelial ovarian cancer: a combined exploratory analysis of 3 prospectively randomized phase 3 multicenter trials: by the Arbeitsgemeinschaft Gynaekologische Onkologie Studiengruppe Ovarialkarzinom (AGO-OVAR) and the Groupe d’Investigateurs Nationaux Pour les Etudes des Cancers de l’Ovaire (GINECO). Cancer. 2009;115:1234–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.24149.

Albright BB, Monuszko KA, Kaplan SJ, Davidson BA, Moss HA, Huang AB, et al. Primary cytoreductive surgery for advanced stage endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:e24 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2021.04.254.

Capozzi VA, Scarpelli E, De Finis A, Rotondella I, Scebba D, Gallinelli A, et al. Optimal management for stage IVB endometrial cancer: a systematic review. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers15215123.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:e1–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006.

Wells GSB, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. Accessed 18 December 2023. https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials. 2007;8:16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-8-16.

Ayhan A, Taskiran C, Celik C, Yuce K, Kucukali T. The influence of cytoreductive surgery on survival and morbidity in stage IVB endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:448–53. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1438.2002.t01-1-01133.x.

Bristow RE, Duska LR, Montz FJ. The role of cytoreductive surgery in the management of stage IV uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;81:92–9. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2000.6110.

Bristow RE, Zerbe MJ, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, Montz FJ. Stage IVB endometrial carcinoma: the role of cytoreductive surgery and determinants of survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:85–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.2000.5843.

Chi DS, Welshinger M, Venkatraman ES, Barakat RR. The role of surgical cytoreduction in Stage IV endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;67:56–60. https://doi.org/10.1006/gyno.1997.4838.

Eto T, Saito T, Kasamatsu T, Nakanishi T, Yokota H, Satoh T, et al. Clinicopathological prognostic factors and the role of cytoreduction in surgical stage IVb endometrial cancer: a retrospective multi-institutional analysis of 248 patients in Japan. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:338–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.012.

Lee LJ, Demaria R, Berkowitz R, Matulonis U, Viswanathan AN. Clinical predictors of long-term survival for stage IVB uterine papillary serous carcinoma confined to the abdomen. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132:65–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.10.035.

McEachron J, Zhou N, Hastings V, Bennett M, Gorelick C, Kanis MJ, et al. Optimal cytoreduction followed by chemoradiation in stage IVB uterine serous carcinoma. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2022;33:100631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctarc.2022.100631.

Moller KA, Gehrig PA, Van Le L, Secord AA, Schorge J. The role of optimal debulking in advanced stage serous carcinoma of the uterus. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:170–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.03.040.

Patsavas K, Woessner J, Gielda B, Rotmensch J, Yordan E, Bitterman P, et al. Optimal surgical debulking in uterine papillary serous carcinoma affects survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;121:581–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.11.048.

Shih KK, Yun E, Gardner GJ, Barakat RR, Chi DS, Leitao MM Jr. Surgical cytoreduction in stage IV endometrioid endometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122:608–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.05.020.

Tanioka M, Katsumata N, Sasajima Y, Ikeda S, Kato T, Onda T, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of women with stage IV endometrial cancer. Med Oncol. 2010;27:1371–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-009-9389-3.

Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Miyatake T, Egawa-Takata T, Ugaki H, Yoshino K, et al. Endometrial carcinoma with extra-abdominal metastasis: improved prognosis following cytoreductive surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1111–7. https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434-009-0892-8.

Abu-Rustum N, Yashar C, Arend R, Barber E, Bradley K, Brooks R, et al. Uterine neoplasms, version 1.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:181–209. https://doi.org/10.6004/jnccn.2023.0006.

Board PDQATE. Endometrial Cancer Treatment (PDQ(R)): Health Professional Version. 2002;doi:NBK65829 [bookaccession].

Haight PJ, Riedinger CJ, Backes FJ, O’Malley DM, Cosgrove CM. The right time for change: a report on the heterogeneity of IVB endometrial cancer and improved risk-stratification provided by new 2023 FIGO staging criteria. Gynecol Oncol. 2023;175:32–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygyno.2023.05.069.

Berek JS, Matias-Guiu X, Creutzberg C, Fotopoulou C, Gaffney D, Kehoe S, et al. FIGO staging of endometrial cancer: 2023. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2023;162:383–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.14923.

Guo J, Cui X, Zhang X, Qian H, Duan H, Zhang Y. The clinical characteristics of endometrial cancer with extraperitoneal metastasis and the value of surgery in treatment. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2020;19:1533033820945784.

Fader AN, Boruta D, Olawaiye AB, Gehrig PA. Uterine papillary serous carcinoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;22:21–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, Timmerman D, Van Limbergen E, Vergote I. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 2005;366:491–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-673667063-8.

Anic K, Flohr F, Schmidt MW, Krajnak S, Schwab R, Schmidt M, et al. Frailty assessment tools predict perioperative outcome in elderly patients with endometrial cancer better than age or BMI alone: a retrospective observational cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149:1551–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00432-022-04038-6.

Cancer Genome Atlas Research N, Kandoth C, Schultz N, Cherniack AD, Akbani R, Liu Y, et al. Integrated genomic characterization of endometrial carcinoma. Nature. 2013;497:67–73. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12113.

Leon-Castillo A, de Boer SM, Powell ME, Mileshkin LR, Mackay HJ, Leary A, et al. Molecular classification of the PORTEC-3 trial for high-risk endometrial cancer: impact on prognosis and benefit from adjuvant therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3388–97. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.20.00549.

Talhouk A, McConechy MK, Leung S, Yang W, Lum A, Senz J, et al. Confirmation of ProMisE: a simple, genomics-based clinical classifier for endometrial cancer. Cancer. 2017;123:802–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.30496.

Horeweg N, Nout RA, Jurgenliemk-Schulz IM, Lutgens L, Jobsen JJ, Haverkort MAD, et al. Molecular classification predicts response to radiotherapy in the randomized PORTEC-1 and PORTEC-2 trials for early-stage endometrioid endometrial cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2023:JCO2300062. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.00062.

Uijterwaal MH, van Dijk D, Lok CAR, De Kroon CD, Kasius JC, Zweemer R, et al. Prognostic value of molecular classification in stage IV endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2023-005058.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ENBP: data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, visualization, writing - original draft, and writing - review & editing; NH: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, Resources, Software, validation, visualization, writing - review & editing. JvdM: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, writing - review & editing; LSN: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, supervision, writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pham, E.N.B., Horeweg, N., van der Marel, J. et al. Survival benefit of cytoreductive surgery in patients with primary stage IV endometrial cancer: a systematic review & meta-analysis. BJC Rep 2, 76 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-024-00084-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-024-00084-4