Abstract

Objectives

Given the wide variation in the incidence of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-associated oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC), we aimed to evaluate the prevalence of HPV and assess treatment outcomes in patients with OPSCC treated with definitive radiotherapy (RT) with or without chemotherapy (CT) at a single institution in India.

Methods

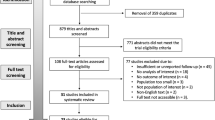

Consecutive patients of OPSCC treated with definitive RT + /-CT in a tertiary care centre from January 2013 to December 2017 were analyzed. Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis, and Log-rank test was used for univariate analysis.

Results

Six-hundred-thirty patients with OPSCC were treated with definitive RT + /-CT. The median age was 56 years (IQR 48–62). As per American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition, 24 (3.8%) were stage I, 63 (10%) were stage II, 113 (18%) were stage III, 375 (59.5%) were stage IVA, and 55 (8.7%) were stage IVB. HPV status was known for 500 patients of which 55 (11%) were p16 immunohistochemistry positive. At a median follow-up of 73.3 months (IQR 58–89), 5-year local control (LC), loco-regional control (LRC), disease-free-survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) were 48.1%, 35.6%, 29.2% and 34.5%, respectively. HPV-positive cohort showed significantly better outcomes compared to HPV-negative cohort with 5-year LC, LRC, DFS, OS of 84.4% vs 43.5% (p < 0.001), 71.3% vs 31.8% (p < 0.001), 63.9% vs 26.1% (p < 0.0001) and 69.1% vs 31.9% (p < 0.001) respectively.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HPV-positive OPSCC by p16 IHC was only 11% in our cohort. The outcomes of HPV-negative cancers are inferior when compared to HPV-positive cancers for a particular stage. Thereby justifying the need for development of treatment-intensifying strategies to improve the inferior outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite a 225% increase in the incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) associated oropharyngeal squamous cell cancer (OPSCC), HPV-negative OPSCC remains significant in some regions with smoking and tobacco use as key risk factors [1,2,3,4]. The prevalence of HPV-associated OPSCC is as high as 50–72% in Western countries compared to 10–20% in Eastern countries [1, 2, 5,6,7,8,9,10]. Outcomes of HPV-negative oropharyngeal cancer are dismal with 5-year overall survival (OS) of 27% to 38% [5, 11]. Recently, data from the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Group (DAHANCA) group showed marked improvement in survival of HPV-positive OPSCC but very little in HPV-negative OPSCC [12]. In the last decade, research on HPV-positive OPSCC has grown significantly [13], while HPV-negative OPSCC remains underexplored, underscoring the need for improved strategies and outcomes.

This retrospective study, conducted at a single tertiary care institute in India, aimed to assess the prevalence of HPV and evaluate the outcomes of OPSCC treated with RT with or without concurrent chemotherapy. The primary objective was to report local control (LC) and locoregional control (LRC). The secondary objectives were to study OS, disease-free survival (DFS), the prevalence of HPV and its impact on outcomes, treatment toxicity and failure patterns.

Materials and methods

After Institutional ethics committee approval, medical records of patients with cT1-T4 and N0-N3 OPSCC treated with curative intent radiotherapy were reviewed. Information regarding patient factors, disease status, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and RTOG acute toxicity were extracted from the Radiation Oncology Information System (ROIS) & electronic medical records (EMR). Patients whose p16 Immunohistochemistry (IHC) status was available in the EMR were collected in the datasheet. For patients whose p16 status was unavailable, p16 IHC testing was performed retrospectively on available tissue sample in accordance with the College of American Pathologists (CAP) guidelines. As per CAP criteria for oropharyngeal cancer, diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic staining in >70% of tumour cells was considered p16 positive [14]. The staging was done using American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition. For the purpose of study, patients were re-staged using AJCC 8th edition staging system [15].

Treatment planning

Patients were assessed in a multi-disciplinary joint clinic, and disease mapping was done to assign a suitable stage. Depending on the stage and physician discretion, patients were planned either for conventional technique on telecobalt or intensity-modulated radiotherapy technique (IMRT) on a linear accelerator. As per physician discretion, dose of 66–70 Gy/30–35 fractions (fx)/6–7 weeks/5–6 fx per week was delivered to gross disease with elective nodal irradiation of bilateral neck to a dose of 54–56 Gy/30–35 fx/6–7 weeks/5–6 fx per week. For IMRT planning, 1 cm margin from primary for clinical target volume (CTV) and 5 mm margin from CTV was used for planning target volume. In patients suitable for brachytherapy, after external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) to a dose 50 Gy and after 1–2 weeks gap, brachytherapy was considered to a dose of 21 Gy/7 fx using 3 Gy per fraction twice daily using 192Ir High dose rate (HDR) brachytherapy [16]. Concurrent chemotherapy was given in fit patients with locally advanced stages [17]. As per medical oncologist recommendations, weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2, three weekly cisplatin at 100 mg/m2, or combination of weekly cisplatin at 40 mg/m2 and nimotuzumab 200 mg were used for concurrent chemotherapy.

Response assessment and follow up

A response assessment was performed at 10–12 weeks after end of RT. Follow-up was every 3 months for 2 years, every 6 months for 3 years and yearly thereafter. Clinical examination findings, patient complaints, and toxicity were documented at each follow-up. Acute toxicity was defined as any maximum grade toxicity occurring during or within 3 months of radiotherapy completion. Late toxicity was defined as any maximum grade toxicity occurring after 3 months of radiotherapy completion till last follow-up. Patients who had recurrent or persistent unresectable disease at the last follow-up and were not contactable telephonically were considered deceased 6 months after the last follow-up.

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tata Memorial Centre (TMC-IEC III; Project No. 900553). A waiver of informed consent was obtained, as this was a retrospective study. The research was conducted in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS).

Statistical analysis

Local failure was defined as disease persistence or relapse within the anatomical oropharynx, patients with regional failure or distant failure, lost to follow up without any recurrence or death due to any cause other than local failure were censored at their last follow up visit. Regional failure was defined as disease persistence or relapse within bilateral level I-V cervical nodes and bilateral retropharyngeal nodes. Locoregional failure was defined as a local failure and/or regional failure, patients with distant failure, lost to follow up without any recurrence or death due to any cause other than locoregional failure were censored at their last follow up visit. The second primary was defined as any second de novo malignant neoplasm other than oropharyngeal cancer. Distant metastasis was any relapse outside the local or regional site due to known oropharyngeal primary. Disease free survival was the duration from the date of diagnosis till the first failure after radiotherapy completion, either local, regional, locoregional, distant failure or death due to any cause. Overall survival was the duration from the date of diagnosis until death due to any cause. For DFS and OS, patients who lost to follow up without any evidence of disease persistence or recurrence were censored at their last follow up visit. All the events were calculated from the date of diagnosis. Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis. All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 25 and R Studio version 2023.03.0 + 386.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2013 and December 2017, 1,080 patients with oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) were registered at our institution. Of these, 150 patients received palliative treatment and 300 were referred to other radiotherapy centers at their native place due to logistical issues, leaving 630 patients who were treated with curative intent at our center and included in the study. One hundred fifty patients (23.8%) had pre-existing comorbidities. The most common comorbidities were hypertension in 49 (32.7%) patients, diabetes in 20 (13.3%) patients, both hypertension and diabetes in 12 (8%) patients, a history of pulmonary tuberculosis in 17 (11.33%) patients, and other conditions in 52 (34.7%) patients. Tobacco-related habits were seen in 562 (89.2%) patients. Overall, tobacco chewing was the most common form of tobacco use, reported in 292 patients (52%). This included 156 patients with exclusive tobacco chewing, 86 patients with combined use of chewing and smoking, and 50 patients with a history of both tobacco chewing and alcohol use. Exclusive tobacco smoking (in the form of bidi or cigarette) was reported in 270 patients (48%). The median duration of tobacco use was 25 years, with an interquartile range (IQR) of 15–32 years. Table 1 shows the details of the patient, tumour and treatment characteristics.

Disease characteristics

At presentation, odynophagia or dysphagia was the most common symptom in 227 (36%) patients, followed by neck swelling in 121 (19%). HPV status was evaluable for 500 patients on available histopathological samples. HPV status was not evaluable for 130 patients due to either non-availability or poor quality of available histopathological samples. Only 55 (11%) patients were HPV positive, while 445 (89%) were HPV negative as per p16 IHC. Forty-four men and 11 women were HPV positive.

Details of staging as per AJCC 7th edition and AJCC 8th edition are shown in Table 1. After restaging as per AJCC 8th edition, there was downstaging in 55 (8.7%) patients due to HPV-positive tumours and upstaging to stage IVB in 92 (14.6%) HPV-negative patients due to clinical extranodal extension.

Treatment characteristics

The conventional radiotherapy technique was used for 466 (74%) patients, IMRT for 135 (21.4%) patients, brachytherapy alone for one patient and IMRT followed by brachytherapy boost for 28 (4.4%) patients. The median dose of EBRT was 70 Gy (range 35–70) Gy with a median of 35 fractions (range 5–35). Thirty-four per cent of node-positive patients were given a posterior triangle electron boost. Conventional fractionation was used for 611 (97%) of the patients, accelerated fractionation for 14 (2.2%), and hypofractionation for 5 (0.8%) of patients. All patients with brachytherapy boost received dose of 21 Gy in 7 fractions with 2 fractions per day 6 hour apart. Depending on the stage (AJCC 7th edition), concurrent chemotherapy was indicated in 544 (86.3%) patients, but 74 (11.7%) of the patients could not receive concurrent chemotherapy due to existing comorbidity or contraindications to chemotherapy. Cisplatin was the most commonly used concurrent chemotherapy regimen, followed by cisplatin and nimotuzumab combination. The median number of chemotherapy cycles was 7 (range 1–8). The median overall treatment time (OTT) was 53 days (IQR 50–57). Five hundred ninety-nine (95%) patients could complete planned treatment. However, 20% of patients had a treatment gap of more than five days during treatment extending a median OTT to 53 days.

Response to treatment & outcomes

Median follow-up was 73.3 months (IQR 57.8–89) for surviving patients & 21 months (IQR 9.2–59) for all patients. Two hundred and thirteen (33.8%) patients were alive without disease, 4(0.6%) patients were alive with disease, 7(1.1%) alive with second primary, 365(57.9%) patients died of disease, and 41 (6.5%) patients died of other non-cancer-related causes. At 12 weeks post-treatment, as per RECIST criteria V1.1, complete response was seen in 354 (56.2%) patients, partial response in 178 (28.3%), progressive disease in 53 (8.4%), stable disease in 4 (0.6%) patients while response assessment was not available for 41 (6.5%) patients.

Local control & locoregional control

The 2-year, 3-year, and 5-year LC and LRC rates were 55% & 41.3%, 50.9% & 38.2% and 48.1 and 35.6%, respectively (Fig. 1).

On univariate analysis, five years LC & LRC were significantly better in HPV-positive group compared to HPV-negative (LC 84.4% vs 43.5% p < 0.001 and 71.3% vs 31.8% p < 0.001, respectively) (Fig. 2a, b). Based on gender and HPV status at five years, LC and LRC were significantly better in HPV-positive females (85.7% & 77.9%) followed by HPV-positive males (83.3% & 69.3%) followed by HPV-negative females (50.7% & 45.1%) and HPV negative males (42.5% & 30.2%) (LC & LRC p < 0.001). Outcomes based on AJCC 7th and 8th edition staging are given in Table 2.

Disease free survival

For the entire cohort, the 2-year, 3-year and 5-year DFS rates were 38%, 34% and 29.2%, respectively (Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, 5 years DFS was significantly better in HPV-positive group compared to HPV-negative (63.9% vs 26.1% p < 0.0001) (Fig. 2c). Based on gender and HPV status, 5-year DFS was significantly better in HPV-positive females (70.1%), followed by HPV-positive males (62.7%) followed by HPV-negative females (40.7%) and HPV-negative males (24.4%) (p < 0.001).

Overall survival

The 2-year, 3-year and 5-year OS rates were 50.2%, 41.3% and 34.5%, respectively, for the entire cohort (Fig. 1). On univariate analysis, 5 years OS was significantly better in HPV-positive group compared to HPV-negative (69.1% vs 31.9% p < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Based on gender and HPV status, 5 years OS was significantly better in HPV-positive females (72.7%) followed by HPV-positive males (67.2%) followed by HPV-negative females (46.6%) and HPV-negative males (30.2%) (p < 0.001). Overall survival based on AJCC 7th and 8th edition staging are given in Table 2 and Fig. 3a–d

Pattern of failure

A total of 402 (63.8%) patients developed disease recurrence. Locoregional failure was the most common pattern of the first failure, with a median time to failure of 12.1 months. Persistent primary or nodal disease at the time of first follow-up was seen in 247 (39.2%) patients, while 139 (22%) patients developed locoregional recurrence during the follow-up period. Distant failure was seen in 72 (11.4%) patients. The median time to develop distant metastasis was 12 months. The incidence of second malignancy was 46 (7.3%) in our study population.

Acute sequelae

RTOG acute grade 0, grade I, grade II, grade III and grade IV skin toxicity was seen in 1.3% (8), 17% (107), 75.4% (475), 6.2% (39) and 0.2% (1) of patients, respectively. RTOG acute grade 0, grade I, grade II, grade III and grade IV mucositis was seen in 1.6% (10), 5.1% (32), 82.2% (518), 11% (69) and 0.2% (1) of patients, respectively. Nasogastric tube dependency during radiotherapy was observed in 35.7% (225) patients. Nine (1.4%) patients required emergency tracheostomy during treatment. Fifty-nine (9%) patients required hospital admission during CTRT. The median duration of hospitalisation was seven days (IQR 6–11 days). Three deaths occurred during treatment: one due to aspiration pneumonitis, one due to febrile neutropenia, and one defaulted during treatment and died of progression.

Late sequelae

Details of late sequelae were available in 272 (43.2%) patients for skin, 341 (54.1%) for xerostomia, 232 (36.8%) for subcutaneous fibrosis and 222 (35.2%) for swallowing outcomes. RTOG late grade 0, grade I, grade II and grade III-IV skin toxicity was seen in 34 (12.5%), 208 (76.5%), 30 (11%) and 0 of patients, respectively. RTOG late grade 0, grade I, grade II, and grade III-IV xerostomia was seen in 14 (4.1%), 185 (54.2%), 139 (40.8%) and 3 (0.9%) of patients, respectively. RTOG late grade 0, grade I, grade II and grade III-IV subcutaneous fibrosis was seen in 30 (12.9%), 138 (59.5%), 61 (26.3%) and 3 (1.3%) of patients, respectively. At the 6-month follow-up visit, 126 (56.8%) patients reported difficulty for swallowing solid food. Post-treatment, 151 (24%) of patients developed hypothyroidism. The median time to develop hypothyroidism was 9 months from the treatment completion. Six patients develop osteoradionecrosis post-radiotherapy, with a median time to develop osteoradionecrosis of 33 months.

Discussion

This is one of the largest single institution studies evaluating HPV status and reporting treatment outcomes in a predominantly HPV-negative OPSCC. Our study observed a prevalence of only 11% HPV-associated OPSCC. This is in contrast with the data from various western series where a prevalence of 50–72% has been reported [1, 2, 5,6,7,8,9,10]. Higher HPV positivity rates have been reported in the United States compared to European countries [1, 5] while lower HPV prevalence has been reported in the Eastern part of the world [2, 10, 18,19,20]. Centres for Disease Control and prevention (CDC) reports a wide variation of HPV-associated OPSCC depending on race, ethnicity and geography. CDC has reported an incidence of HPV-related OPSCC of 1.8 per 100,000 women and 9.4 per 100,000 males among white people, while in black people, it is reported as 1.4 and 6.6, respectively. In Americans, they have reported an incidence of 1 per 100,000 women and 5.3 per 100,000 in males, while in the Asian population, it is reported as 0.6 and 2.2, respectively [21]. In a systematic review Kreimer et al. observed HPV prevalence of 47% in the North America, 28.2% in the Europe and 46.3% in Asia [22]. These difference could possibly be due to differences in the sexual practices. However we could not get information related to the sexual practices in our study.

At a median follow-up of 73.3 months for surviving patients (IQR 57.8–89), 5-year LC, LRC, DFS and OS in our study were 48.1%, 35.6%, 29.2% and 34.5%, respectively.

The five-year LC, LRC, DFS and OS rates were 84%, 71% 64%, 69% in HPV-positive patients and 44%, 32%, 26% and 32% in HPV-negative patients, respectively. The results of our current study correspond with published literature on oropharyngeal cancer who were treated with radiotherapy, as summarised in Table 3.

Agarwal et al. published OPSCC outcomes from our institute in 2009 and showed 3-year LC, LRC, DFS and OS of 49%, 41%, 39% and 36.1%, respectively. History of tobacco abuse, Karnofsky performance score (KPS) < 80, N stage, radiotherapy dose < 66 Gy, OTT > 50 days were independent prognostic factors for DFS and LRC in this study [23]. The prognostic factors for the present study will be addressed in a separate report.

Many studies have reported excellent disease control and survival with HPV-positive OPSCC [5, 6, 11, 12, 15, 24,25,26,27]. In our study, 3-year OS & DFS were 75.7% & 72.4% in HPV-positive and 39.1% & 30.6% in HPV-negative subgroups, respectively. In a study by Ang K et al., 3-year OS & PFS rates were 83.6% & 74.4% in HPV-positive and 51.3% & 38.4% in HPV-negative subgroups, respectively [6]. They also developed the risk stratification based on HPV status and smoking habits for OPSCC, which showed a 3-year OS rate of 93%, 70.8% and 46.2% in low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk OPSCC, respectively. With prolonged tobacco usage and HPV-negative cancers, majority of our patients belong to the high-risk stratification of Ang et al. [6].

In our study as per AJCC 7th edition, 5-year OS rates in HPV-positive and HPV-negative subgroups were unknown (no patient in stage I as per AJCC 7th edition) & 63.2% in stage I, 68.6% & 45.9% in stage II, 77.8 & 44.7% in stage III, 61.4% & 25.4% in stage IVA and 88.9% & 16.7% in stage IVB in respectively. As per AJCC 7th edition, O’Sullivan B et al. reported 5-year OS in HPV-positive and HPV-negative 88% & 76% in stage I, 82% & 68% in stage II, 84% & 53% in stage III, 81% & 45% in stage IVA and 60% & 34% in stage IVB. They developed a new staging (AJCC 8th edition) for HPV-Positive OPSCC and showed 5-year OS rates were 85% in stage I, 78% in stage II and 53% in stage III [15]. In our study after restaging as per AJCC 8th edition in 55 HPV-positive OPSCC patients, 5-year OS rates were 68.1% in stage I, 60.6% in stage II and 69% in stage III respectively. Lower OS even in the HPV-positive group in our study could possibly be due to the impact of prolonged tobacco usage in 89.2% of the patients with median duration of 25 (IQR 15-32) years. Gillison et al. showed a 2% decrease in OS per year of smoking [25].

While there has been an increase in the OPSCC in the last 1–2 decades, primarily due to the rise in the HPV-associated OPSCC. However, a decrease in HPV-negative cancers has been reported only in the USA [1]. This has been attributed to the decrease in the smoking rates in the USA. DAHANCA group has reported no change in the incidence of HPV-negative cancers [12]. Considering this there is still a significant proportion of the patient population with HPV-negative cancers who have poor outcomes and need strategies to improve their outcomes. Our study highlights the need for treatment escalation in patients with HPV-negative cancers. The 3-year OS of 39.1% in the HPV-negative cohort is significantly inferior compared to the HPV-positive cohort, prompting efforts to improve survival in HPV-negative cancers. Hyperfractionated radiotherapy has shown a survival benefit in head and neck cancers [28, 29]. DAHANCA group reported outcomes of dose escalation with hyperfractionation and concurrent chemotherapy and nimorazole in patients with HPV-negative cancers [30]. While the acute toxicity was high (72% required tube feeding), the 3-year locoregional failure rate was 21%, and OS was 74% in their series. Treatment intensification with addition of Nimotuzumab to CTRT improved 2-year OS from 39% to 57.6% [10]. The addition of brachytherapy can also be considered as a dose escalation strategy in well selected HPV-negative cancers. In a randomised trial of early-stage oropharyngeal cancer addition of brachytherapy resulted in 9% improvement in the LC [16]. Few prospective treatment escalation studies are ongoing, which test different strategies such as adding surgery [31, 32], immunotherapy [32], PET-based RT dose escalation [33] and stereotactic radiosurgery boost [34] for treatment escalation in HPV-negative OPSCC.

One of the limitations of the study is its retrospective nature. However, the majority of the studies of HPV in the OPSCC have been based on retrospective cohorts. We however have included consecutive patients treated with radical intent in a tertiary care centre. This analysis also includes patients who could not complete planned treatment due to death, progression, logistic reasons, or toxicity. This reduces the inherent selection bias of retrospective studies and reflects real-world scenarios in routine clinical practice.

In this study, we did HPV testing using p16 IHC as per CAP guidelines. However, there are studies reporting discordance of 7-10% between p16 IHC and the HPV-DNA by PCR [35, 36]. This may have an impact on outcomes, especially in patients with high tobacco exposure. Another limitation is the lack of data on sexual practices, late effects, poor recall history of tobacco habits and quality of life. In addition, most of the patients in our series were treated using conventional radiotherapy techniques. This limits the comparison of our outcomes in the era of IMRT.

Conclusion

The prevalence of HPV-positive OPSCC was only 11% in our cohort. The outcomes of HPV-negative OPSCC are inferior when compared to HPV-positive OPSCC. Strategies need to be developed to intensify treatment to improve the outcomes of HPV-negative OPSCC.

Data availability

The data from this study will not be shared publicly as the study did not have any data sharing plan at the time of IEC approval. However, data will be shared following reasonable request to the corresponding author, who will then take necessary permissions for data sharing in secure and legally acceptable conditions.

References

Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, Hernandez BY, Xiao W, Kim E, et al. Human papillomavirus and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4294–301.

Murthy V, Calcuttawala A, Chadha K, d’Cruz A, Krishnamurthy A, Mallick I, et al. Human papillomavirus in head and neck cancer in India: Current status and consensus recommendations. South Asian J Cancer. 2017;6:93–8.

Ni G, Huang K, Luan Y, Cao Z, Chen S, Ma B, et al. Human papillomavirus infection among head and neck squamous cell carcinomas in southern China. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0221045.

Dong H, Shu X, Xu Q, Zhu C, Kaufmann AM, Zheng ZM, et al. Current status of human papillomavirus-related head and neck cancer: from viral genome to patient care. Virol Sin. 2021;36:1284–302.

Lassen P, Lacas B, Pignon JP, Trotti A, Zackrisson B, Zhang Q, et al. Prognostic impact of HPV-associated p16-expression and smoking status on outcomes following radiotherapy for oropharyngeal cancer: The MARCH-HPV project. Radiother Oncol. 2018;126:107–15.

Ang KK, Harris J, Wheeler R, Weber R, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tân PF, et al. Human papillomavirus and survival of patients with oropharyngeal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:24–35.

Stein AP, Saha S, Kraninger JL, Swick AD, Yu M, Lambert PF, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review. Cancer J. 2015;21:138–46.

Schache AG, Powell NG, Cuschieri KS, Robinson M, Leary S, Mehanna H, et al. HPV-related oropharynx cancer in the United Kingdom: an evolution in the understanding of disease etiology. Cancer Res. 2016;76:6598–606.

Carlander ALF, Grønhøj Larsen C, Jensen DH, Garnæs E, Kiss K, Andersen L, et al. Continuing rise in oropharyngeal cancer in a high HPV prevalence area: A Danish population-based study from 2011 to 2014. Eur J Cancer. 2017;70:75–82.

Noronha V, Patil VM, Joshi A, Mahimkar M, Patel U, Pandey MK, et al. Nimotuzumab-cisplatin-radiation versus cisplatin-radiation in HPV negative oropharyngeal cancer. Oncotarget. 2020;11:399–408.

Högmo A, Holmberg E, Haugen Cange H, Reizenstein J, Wennerberg J, Beran M, et al. Base of tongue squamous cell carcinomas, outcome depending on treatment strategy and p16 status. A population-based study from the Swedish Head and Neck Cancer Register. Acta Oncologica. 2022;61:433–40.

Lassen P, Alsner J, Kristensen CA, Andersen E, Primdahl H, Johansen J, et al. OC-0105 Incidence and survival after HPV+ and HPV- oropharynx cancer in Denmark 1986-2020 - A DAHANCA study. Radiother Oncol. 2023;182:S66–S67.

Lassen P, Huang SH, Su J, Waldron J, Andersen M, Primdahl H, et al. Treatment outcomes and survival following definitive (chemo)radiotherapy in HPV-positive oropharynx cancer: Large-scale comparison of DAHANCA vs PMH cohorts. Int J Cancer. 2025:150;1329–40.

Lewis JS, Beadle B, Bishop JA, Chernock RD, Colasacco C, Lacchetti C, et al. Human Papillomavirus Testing in Head and Neck Carcinomas: Guideline From the College of American Pathologists. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:559–97.

O’Sullivan B, Huang SH, Su J, Garden AS, Sturgis EM, Dahlstrom K, et al. Development and validation of a staging system for HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer by the International Collaboration on Oropharyngeal cancer Network for Staging (ICON-S): a multicentre cohort study. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17:440–51.

Budrukkar A, Murthy V, Kashid S, Swain M, Rangarajan V, Ghosh Laskar S, et al. OC-0100 IMRT vs IMRT and brachytherapy for early oropharyngeal cancers (Brachytrial): A randomized trial. Radioth Oncol. 2022;170:S74–5.

Noronha V, Joshi A, Patil VM, Agarwal J, Ghosh-Laskar S, Budrukkar A, et al. Once-a-week versus once-every-3-weeks cisplatin chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: a phase III randomized noninferiority trial. JCO. 2018;36:1064–72.

Chien CY, Su CY, Fang FM, Huang HY, Chuang HC, Chen CM, et al. Lower prevalence but favorable survival for human papillomavirus-related squamous cell carcinoma of tonsil in Taiwan. Oral Oncology. 2008;44:174–9.

Bhosale PG, Pandey M, Desai RS, Patil A, Kane S, Prabhash K, et al. Low prevalence of transcriptionally active human papilloma virus in Indian patients with HNSCC and leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;122:609–18.e7.

Nandi S, Mandal A, Chhebbi M. The prevalence and clinicopathological correlation of human papillomavirus in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in India: A systematic review article. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;26:100301.

Cancers Associated with Human Papillomavirus, United States—2015–2019 | CDC. 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no31-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2015-2019.htm.

Kreimer AR, Clifford GM, Boyle P, Franceschi S. Human papillomavirus types in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas worldwide: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14:467–75.

Agarwal JP, Mallick I, Bhutani R, Ghosh-Laskar S, Gupta T, Budrukkar A, et al. Prognostic factors in oropharyngeal cancer – analysis of 627 cases receiving definitive radiotherapy. Acta Oncologica. 2009;48:1026–33.

Fakhry C, Westra WH, Li S, Cmelak A, Ridge JA, Pinto H, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–9.

Gillison ML, Zhang Q, Jordan R, Xiao W, Westra WH, Trotti A, et al. Tobacco smoking and increased risk of death and progression for patients with p16-positive and p16-negative oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2102–11.

Lassen P, Eriksen JG, Krogdahl A, Therkildsen MH, Ulhøi BP, Overgaard M, et al. The influence of HPV-associated p16-expression on accelerated fractionated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: Evaluation of the randomised DAHANCA 6&7 trial. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:49–55.

Posner MR, Lorch JH, Goloubeva O, Tan M, Schumaker LM, Sarlis NJ, et al. Survival and human papillomavirus in oropharynx cancer in TAX 324: a subset analysis from an international phase III trial. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1071–7.

Bourhis J, Overgaard J, Audry H, Ang KK, Saunders M, Bernier J, et al. Hyperfractionated or accelerated radiotherapy in head and neck cancer: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2006;368:843–54.

Petit C, Lacas B, Pignon JP, Le QT, Grégoire V, Grau C, et al. Chemotherapy and radiotherapy in locally advanced head and neck cancer: an individual patient data network meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:727–36.

Saksø M, Jensen K, Andersen M, Hansen CR, Eriksen JG, Overgaard J. DAHANCA 28: A phase I/II feasibility study of hyperfractionated, accelerated radiotherapy with concomitant cisplatin and nimorazole (HART-CN) for patients with locally advanced, HPV/p16-negative squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx, hypopharynx, larynx and oral cavity. Radiother Oncol. 2020;148:65–72.

Nair DD. Primary Surgery Vs Primary Chemoradiation for Oropharyngeal Cancer (Scope Trial) - A Phase II/III Integrated Design Randomized Control Trial. clinicaltrials.gov; 2021. Report No.: NCT05144100. Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05144100.

University of Birmingham. Phase III Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Alternative Regimens for Escalating Treatment of Intermediate and High-risk Oropharyngeal Cancer. clinicaltrials.gov; 2022. Report No.: NCT04116047. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04116047

Tata Medical Center. Intensifying Radiation Treatment in Advanced/ Poor Prognosis Laryngeal, Hypopharyngeal (LH) and Oropharyngeal Cancers (OPC) Using PET -CT Based Dose Escalation Strategies (INTELHOPE). clinicaltrials.gov; 2021. Report No.: NCT02757222. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02757222.

Ghaly M A. Phase I Trial of IMRT With Dose-Escalated Image-Guided Stereotactic Radiosurgery (SRS) Boost for Human Papilloma Virus (HPV)- Unassociated Oropharyngeal Cancer. clinicaltrials.gov; 2023. Report No.: NCT02703493. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02703493.

Mehanna H, Taberna M, von Buchwald C, Tous S, Brooks J, Mena M, et al. Prognostic implications of p16 and HPV discordance in oropharyngeal cancer (HNCIG-EPIC-OPC): a multicentre, multinational, individual patient data analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2023;24:239–51.

Patel U, Mittal N, Rane SU, Patil A, Gera P, Kannan S, et al. Correlation of transcriptionally active human papillomavirus status with the clinical and molecular profiles of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Head Neck. 2021;43:2032–44.

Funding

The study is funded by an intramural grant from Tata Memorial Centre, Homi Bhabha National Institute, Parel, Mumbai, India. Part of HPV evaluation by p16 IHC was covered under another project, which was funded by the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, New Delhi and the Science and Engineering Research Board, New Delhi. The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Guarantor of integrity of the entire study: AB Study concepts and design: AB, SRK, AS, SGL, JPA, MS Literature research: AB, SGL, MS, VM, TG, NM, MM, AP, UP, VP, AJ, VN, SS, KP, JPA Clinical studies: AB, SGL, MS, VM, TG, NM, MM, AP, UP, VP, AJ, VN, SS, KP, JPA Experimental studies/data analysis: AB, SRK Statistical analysis: AB, SRK, SGL, MS, JPA Manuscript preparation: AB, SRK Manuscript editing: All authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Tata Memorial Centre (TMC-IEC III; Project No. 900553). A waiver of informed consent was obtained, as this was a retrospective study. The research was conducted in accordance with the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (CIOMS).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Budrukkar, A., Kashid, S.R., Swain, M. et al. Long-term outcomes of consecutive patients of oropharyngeal cancer treated with radical radiotherapy. BJC Rep 3, 54 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-025-00164-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44276-025-00164-z