Abstract

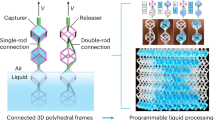

Liquids are widely applied in the construction of various functional devices due to their abilities to flow, dissolve, deform and phase separate; however, the fabrication of liquid-based devices can be costly and lack reconfigurability due to the need for predesigned solid enclosing walls. Herein we report a strategy to generate and manipulate functional liquid devices by assembling and disassembling different types of liquid droplets like toy building blocks; we also uncover the underlying mechanisms. Multiphase liquid devices with diverse compositions and geometries can be quickly constructed and reconfigured in a pillared substrate, enabling the ability to freely structure liquids and precisely program liquid–liquid interfaces. The applications in fluidic devices, microreactors and their combinations are demonstrated.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the main text and its Supplementary Information. Source Data are provided with this paper.

References

Austen Angell, C., Ansari, Y. & Zhao, Z. Ionic liquids: past, present and future. Faraday Discuss. 154, 9–27 (2012).

Astoricchio, E., Alfano, C., Rajendran, L., Temussi, P. A. & Pastore, A. The wide world of coacervates: from the sea to neurodegeneration. Trends Biochem. Sci 45, 706–717 (2020).

Gao, N. & Mann, S. Membranized coacervate microdroplets: from versatile protocell models to cytomimetic materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 56, 297–307 (2023).

Abbas, M., Lipiński, W. P., Wang, J. & Spruijt, E. Peptide-based coacervates as biomimetic protocells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 3690–3705 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Reconfigurable ferromagnetic liquid droplets. Science 365, 264–267 (2019).

Daeneke, T. et al. Liquid metals: fundamentals and applications in chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 4073–4111 (2018).

Wang, L., Lai, R., Zhang, L., Zeng, M. & Fu, L. Emerging liquid metal biomaterials: from design to application. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201956 (2022).

Forth, J. et al. Building reconfigurable devices using complex liquid–fluid interfaces. Adv. Mater. 31, 1806370 (2019).

Zarbin, A. J. G. Liquid–liquid interfaces: a unique and advantageous environment to prepare and process thin films of complex materials. Mater. Horiz. 8, 1409–1432 (2021).

Piradashvili, K., Alexandrino, E. M., Wurm, F. R. & Landfester, K. Reactions and polymerizations at the liquid–liquid interface. Chem. Rev. 116, 2141–2169 (2016).

Rao, C. N. R. & Kalyanikutty, K. P. The liquid–liquid interface as a medium to generate nanocrystalline films of inorganic materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 489–499 (2008).

Yang, H., Fu, L., Wei, L., Liang, J. & Binks, B. P. Compartmentalization of incompatible reagents within pickering emulsion droplets for one-pot cascade reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1362–1371 (2015).

Dudukovic, N. A. et al. Cellular fluidics. Nature 595, 58–65 (2021).

Villar, G., Graham, A. D. & Bayley, H. A tissue-like printed material. Science 340, 48–52 (2013).

Villar, G., Heron, A. J. & Bayley, H. Formation of droplet networks that function in aqueous environments. Nat. Nanotech. 6, 803–808 (2011).

Montelongo, Y. et al. Electrotunable nanoplasmonic liquid mirror. Nat. Mater. 16, 1127–1135 (2017).

Paratore, F., Bacheva, V., Bercovici, M. & Kaigala, G. V. Reconfigurable microfluidics. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 70–80 (2021).

Yasuga, H. et al. Fluid interfacial energy drives the emergence of three-dimensional periodic structures in micropillar scaffolds. Nat. Phys. 17, 794–800 (2021).

Xu, J., Xiu, S., Lian, Z., Yu, H. & Cao, J. Bioinspired materials for droplet manipulation: principles, methods and applications. Droplet 1, 11–37 (2022).

Si, Y., Li, C., Hu, J., Zhang, C. & Dong, Z. Bioinspired superwetting open microfluidics: from concepts, phenomena to applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2301017 (2023).

Feng, S. et al. Three-dimensional capillary ratchet-induced liquid directional steering. Science 373, 1344–1348 (2021).

Quéré, D. Wetting and roughness. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 38, 71–99 (2008).

Vrancken, R. J. et al. Anisotropic wetting and de-wetting of drops on substrates patterned with polygonal posts. Soft Matter 9, 674–683 (2013).

Ueda, E. & Levkin, P. A. Emerging applications of superhydrophilic–superhydrophobic micropatterns. Adv. Mater. 25, 1234–1247 (2013).

Efremov, A. N., Grunze, M. & Levkin, P. A. Digital liquid patterning: a versatile method for maskless generation of liquid patterns and gradients. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 1, 1300075 (2014).

Li, J., Ha, N. S., Liu, T. L., Van Dam, R. M. & Cj Kim, C.-J. Ionic-surfactant-mediated electro-dewetting for digital microfluidics. Nature 572, 507–510 (2019).

Feng, W. et al. Harnessing liquid-in-liquid printing and micropatterned substrates to fabricate 3-dimensional all-liquid fluidic devices. Nat. Commun. 10, 1802172 (2019).

Walsh, E. J. et al. Microfluidics with fluid walls. Nat. Commun. 8, 816 (2017).

Dunne, P. et al. Liquid flow and control without solid walls. Nature 581, 58–62 (2020).

Cai, L., Marthelot, J. & Brun, P.-T. An unbounded approach to microfluidics using the Rayleigh–Plateau instability of viscous threads directly drawn in a bath. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 116, 22966–22971 (2019).

Jose, B. M. & Cubaud, T. Role of viscosity coefficients during spreading and coalescence of droplets in liquids. Phys. Rev. Fluids 2, 111601 (2017).

Huang, Z. et al. A general patterning approach by manipulating the evolution of two-dimensional liquid foams. Nat. Commun. 8, 14110 (2017).

Wong, T. S. et al. Bioinspired self-repairing slippery surfaces with pressure-stable omniphobicity. Nature 477, 443–447 (2011).

Navalpotro, P., Palma, J., Anderson, M. & Marcilla, R. A membrane‐free redox flow battery with two immiscible redox electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 12460–12465 (2017).

Hirt, C. W. & Nichols, B. D. Volume of fluid (VOF) method for the dynamics of free boundaries. J. Comput. Phys. 39, 201–225 (1981).

ANSYS FLUENT 18.0 Theory Guide (ANSYS, 2017).

Brackbill, J. U., Kothe, D. B. & Zemach, C. A continuum method for modeling surface tension. J. Comput. Phys. 100, 335–354 (1992).

Acknowledgements

We thank C. Zhang for the help with the CFD simulations, and Z. Chen for an inspiring discussion on fluidic device applications. Z.G. thanks the support of National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YFA0700500) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 52033002). X.D. is grateful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 22372032, 22002015) and the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant no. BK20211560). Y.Z. is grateful for the support of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 22202040), the Young Elite Scientists Sponsorship Program by CAST (grant no. 2022QNRC001), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (grant nos. 2022M710688 and 2022TQ0064) and the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (grant no. 2022ZB126).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D., Z.G., Y.Z. and S.L. conceptualized and designed this work. Y.Z., S.L., Z.C., Y.N., K.L., J. Zhou, Z.H., J. Zhang and S.D. performed the experiments. Y.Z., S.L., Z.C. and X.D. wrote the original paper. X.D. and Z.G. supervised the work. All authors analyzed the data and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Southeast University has filed patent applications on this work. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Engineering thanks Thomas Cubaud, Govind Kaigala and Zuankai Wang for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Numerical simulation on 2D water layer in a pillared substrate.

a, 2D physical model for simulation analysis. i: schematic demonstration, L = 10 mm, W = 6 mm. ii: meshing in the computational domain. b, The calculated pressure field (3 s after simulation starts) inside 2D water layer in the pillared substrates with θ = 100° (i) and θ = 150° (ii) respectively. In a highly hydrophobic pillared substrate, the oil-water interface exhibits much higher pressure and therefore a stronger tendency to contract. c, Images showing the simulated results of the changes in the volume fraction of oil phase within the computational domain in the pillared substrates with θ = 100° (top) and θ = 150° (bottom) respectively. In a highly hydrophobic pillared substrate, after simulation starts, the fraction of oil phase at the border of the water units significantly increases, compared with the limited changes in medium hydrophobic substrate. This indicates that the water units in highly hydrophobic pillared substrate have a strong tendency to contract. Notably, the simulation is performed on a 2D layer, thus the kinectics of the liquid behavior is distinct to the situation in 3D condition. More details see Methods.

Extended Data Fig. 2 CFD simulation on the combination of two water units in a pillared substrate.

The WCAs of the substrate materials are (a) 170°, (b) 100° and (c) 30°. The droplets are added one by one, and the results are shown from top view (side view, 3D view and animations are shown in Supplementary Video 2). Notably, in the simulation, the pillared substrate was assumed to be perfect, with a homogeneous surface property and no structural defect, which is not exactly the same as observed experimental conditions (as shown in Fig. 1c). More details see Methods.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Expansion of water–oil interface in pillar arrays with different geometries.

a, Size and geometry of the pillars (height: 5 mm). b, Photos indicating the position of the water–oil interface in the pillar array during continuous water addition.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Changes of LP of thin water layers during the expansion of water–oil interfaces in different pillar arrays.

The left is the top view of the water layer at different stages, and the right is the calculated \(\Delta p\) value. a, Square pillar. b, Diamond pillar. c, Hexagon pillar. \(A=\frac{4\gamma }{1{mm}}\). \(\Delta p\): the Laplace pressure of the curved water–oil interface. \(\gamma\): the surface tension of water. \(\theta\): the WCA of the substrate material. \(\alpha\): the angle indicating the position of the water–oil interface in the pillar array.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The cutting process in water units.

a, Photos of a water channel before and after being cut off with a fluorinated paper sheet. The red and blue points revealed the positions of tri-phase contact points from top view. Scale bars: 1 mm. b-d, A simplified model for the cutting process. b, The top view of a thin water layer when the water unit is completely cut off by a fluorinated paper sheet. c, The cross-sectional view of a thin water layer during the cutting process. d, A simplified model for the calculation of \(\Delta {p}_{1}\) in (c). \(\Delta p\): the Laplace pressure of the curved water–oil interface. \(\gamma\): the surface tension of water. \({r}_{{\rm{p}}}\): the radius of the pillar. \(l\): the distance between pillar centers. \(\theta\): the WCA of the substrate material. \(\alpha\): the angle indicating the position of the water–oil interface in the pillar array. \(\beta\): the WCA of the hydrophobic paper sheet. \({F}_{{up}}\) and \({F}_{{down}}\): the upward and downward forces borne by the water–oil interface on the paper sheet, respectively. More details see Supplementary Note 3.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Notes 1–3, Figs. 1–28 and Table 1.

Supplementary Video 1

Generation of water units and channels in a pillared substrate.

Supplementary Video 2

CFD simulation on the combination of two water units in a pillared substrate.

Supplementary Video 3

Visualizing liquid flow in 2D water channels.

Supplementary Video 4

Manual fabrication of water channel in a pillared substrate.

Supplementary Video 5

Automatic fabrication of complex fluidic structure in a pillared substrate.

Supplementary Video 6

Pumping solution into a fluidic structure in a pillared substrate.

Supplementary Video 7

Visualizing liquid flow in 3D water channels.

Supplementary Video 8

Disconnecting the water channel through a cutting process.

Supplementary Video 9

In situ reconfiguring the design of a fluidic channel in a pillared substrate.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Extended Data Fig./Table 4

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, Y., Li, S., Chong, Z. et al. Reconfigurable liquid devices from liquid building blocks. Nat Chem Eng 1, 149–158 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-023-00023-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-023-00023-z

This article is cited by

-

Antigravity confined interfacial self-assembly approach for the synthesis and characterization of nanofilms

Nature Communications (2026)

-

Structured liquid-based reconfigurable all-liquid optical fibers

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Reconfiguring liquid devices

Nature Chemical Engineering (2024)