Abstract

Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) can produce important one-carbon (C1) feedstocks for sustainable biomanufacturing, such as formate. Unfortunately, natural formate assimilation pathways are inefficient and constrained to organisms that are difficult to engineer. Here we establish a synthetic reductive formate pathway (ReForm) in vitro. ReForm is a six-step pathway consisting of five engineered enzymes catalyzing nonnatural reactions to convert formate into the universal biological building block acetyl-CoA. We establish ReForm by selecting enzymes among 66 candidates from prokaryotic and eukaryotic origins. Through iterative cycles of engineering, we create and evaluate 3,173 sequence-defined enzyme mutants, tune cofactor concentrations and adjust enzyme loadings to increase pathway activity toward the model end product malate. We demonstrate that ReForm can accept diverse C1 substrates, including formaldehyde, methanol and formate produced from the electrochemical reduction of CO2. Our work expands the repertoire of synthetic C1 utilization pathways, with implications for synthetic biology and the development of a formate-based bioeconomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The accelerating climate crisis poses one of the most urgent economic and social challenges to humankind, driven by the unabated release and accumulation of CO2 in our atmosphere1. While important strides have been made in carbon-free energy production2,3, there remains a critical need for cradle-to-gate carbon-negative manufacturing of goods. An emerging potential solution lies at the intersection of chemistry and biology, where the electrochemical conversion of CO2 into soluble organic molecules provides substrates for enzymatic cascades to produce value-added chemicals4,5. Among these options, formate stands out as a promising bridge toward establishing a sustainable bioeconomy6,7. Formate can be efficiently generated through electrocatalysis8, exhibits high solubility in water and simultaneously provides both a carbon source and reducing power. However, challenges exist in using formate as a substrate for biosynthesis. Nature has evolved only a limited number of formate-fixing reactions, and the organisms discovered to use these reactions are difficult to engineer and poorly suited for industrial applications9.

Recent efforts to develop a platform for formate utilization have focused on integrating formate assimilation pathways into workhorse biotechnology microbes such as Escherichia coli10,11 and Cupriavidus necator12. Despite notable progress in adapting the metabolism of these organisms, the production of value-added chemicals by synthetic formatotrophs has remained limited due to unfavorable thermodynamic driving forces, environmental sensitivity and the inherent complexity of natural pathways10,13.

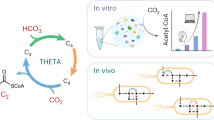

Synthetic biology offers a potential way to bypass existing bottlenecks in natural formate assimilation pathways by designing new-to-nature solutions. There are many examples of designer metabolic pathways that can explore space not sampled by evolution5,14 Because such pathways are freed from evolutionary constraints, it also becomes possible to create pathways with superior thermodynamic or kinetic characteristics compared with those found in nature. For example, the crotonyl-CoA/ethylmalonyl-CoA/hydroxybutyryl-CoA (CETCH) cycle15 and the reductive tricarboxylic acid branch/4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA/ethylmalonyl-CoA/acetyl-CoA (THETA) cycle16 are synthetic reaction networks of 17 enzymes each that directly convert CO2 into organic molecules. Both designed cycles have been shown to be more efficient than the most abundant natural carbon fixation cycle, the Calvin–Benson–Bassham (CBB) cycle.

Linear synthetic pathways have also been described (Supplementary Fig. 1), including those that assimilate one-carbon (C1) substrates. For example, the formyl-CoA elongation (FORCE) pathway17 and the synthetic acetyl-CoA (SACA)18 pathway have achieved high product titers using formaldehyde as a substrate. The former is designed around the acyloin condensation between formyl-CoA and formaldehyde, while the latter is designed around the self-condensation of formaldehyde. Although formaldehyde benefits from a higher reactivity than formate, it suffers from toxicity to proteins and requires an additional sacrificial substrate to generate reducing power.

The construction of synthetic metabolic pathways that start with formate could address these challenges. However, the enzymatic conversion of formate into formaldehyde has been difficult due to the lack of natural enzymes that can carry out the transformations required19,20,21. The core bottleneck is that formate must first be activated before it can be reduced to formaldehyde, owing to its low reduction potential13. One approach to overcome this limitation is the activation of formate using ATP. For example, recent work used a promiscuous acetate kinase to convert formate to formyl-phosphate followed by its reduction to formaldehyde with an engineered N-acetyl-γ-glutamyl phosphate reductase21. These reactions were connected to the FORCE pathway to produce glycolate from formate, but the difficulty in engineering this nonnative reduction resulted in low rates (kcat = 0.12 s−1). An alternative approach to produce formaldehyde is to first activate formate to formyl-CoA using an acetyl-CoA synthetase, followed by its reduction to formaldehyde with an acyl-CoA reductase19,22. Unfortunately, residual activity of acyl-CoA reductases with acetyl-CoA and low activity of these enzymes with their nonnative substrates have presented challenges thus far22.

Here, we set out to create a new-to-nature anabolic pathway from formate. We had three goals. First, we sought to enable the direct conversion of formate to acetyl-CoA and a subsequent end product. Reaching acetyl-CoA, a critical branchpoint between catabolism and anabolism, unlocks access to an immense breadth of metabolic pathways that have been developed over the past decades to produce value-added chemicals23. As a model end product, we selected malate, which had a market of more than 600 million US dollars in 202224. Second, we aimed to build a pathway with as many nonnatural enzymatic transformations as possible. This would require us to develop efficient tools for enzyme engineering that support the construction of synthetic pathways. Third, we aspired to demonstrate that the pathway can accept formate produced by the electrochemical reduction of CO2, as well as additional C1 substrates including formaldehyde and methanol. Key design criteria included that the pathway be (1) thermodynamically favorable, (2) tolerant to aerobic environments, (3) composed of a minimal number of enzymes and (4) independent from catalytic starting intermediates. By combining cell-free protein synthesis, extensive protein engineering and pathway tuning, we report the conceptualization, design and optimization of the reductive formate pathway (ReForm) in vitro.

Results

Establishing a synthetic formate assimilation pathway

ReForm (Fig. 1a) consists of six individual enzyme-catalyzed reactions, with five core reactions requiring engineered enzymes operating on nonnative substrates. The pathway was conceptualized around the engineered C1–C1 bond forming enzyme oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase (oxc), a variant of which was shown to catalyze the acyloin condensation between formyl-CoA and formaldehyde with a superior catalytic efficiency compared with similar C1–C1 bond-forming enzymes25,26 (Supplementary Figs. 2–4). Our initial design started with the activation of formate to formyl-CoA with an acyl-CoA synthetase (acs), followed by its reduction to formaldehyde with an acyl-CoA reductase (acr). Oxc ligates formyl-CoA and formaldehyde to form glycolyl-CoA, which is reduced to glycolaldehyde by an acr. Glycolaldehyde can then be dehydrated and phosphorylated to form acetyl-phosphate by a phosphoketolase (pk). A phosphotransacetylase (pta) then transfers a CoA onto acetyl-phosphate to form acetyl-CoA.

a, Synthetic metabolic pathway to convert formate into acetyl-CoA, composed of six reactions. b, Each enzyme addition is labeled on the set of traces, starting with a no-enzyme control. Extracted ion counts were determined for an m/z [M + H]+ of 797.1 for formyl-CoA, 828.1 for glycolyl-CoA and 812.1 for acetyl-CoA, which corresponds to the mass of the CoA-thioester with the incorporation of 1 (formyl-CoA) or 2 (glycolyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA) 13C from 13C-formate. Formyl-CoA is shown in light gray and glycolyl-CoA in dark gray. Traces are representative of n = 3 independent reactions.

Conceptually, our pathway resembles a combination of the upper branch of the FORCE pathway (ligation of formyl-CoA and formaldehyde) and the lower branch of the SACA pathway (conversion of glycolaldehyde to acetyl-CoA). However, ReForm uniquely begins with formate, which must be initially activated by the combined action of an acs and acr (Supplementary Fig. 1). Synthetic designs, such as ReForm, expand the diversity of metabolic solutions for formate assimilation, potentially offering a tailored fit to different desired products.

We began assembling ReForm by searching the literature for enzymes with a demonstrated capacity to catalyze the hypothetical reactions in Fig. 1a based on promiscuity (that is, a given enzyme can perform similar chemistries on molecules similar to the native substrate). We selected an acs from Erythrobacter sp. NAP1 that natively transforms acetate to acetyl-CoA (instead of formate to formyl-CoA)27, an acr from R. palustris that natively reduces propionyl-CoA to propionaldehyde (instead of reducing formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA)28 and a pk from B. adolescentis that natively cleaves D-fructose 6-Pi into acetyl-Pi and erythrose 4-Pi (instead of glycolaldehyde into acetyl-Pi)18. Our initial enzyme candidates originate from diverse efforts in building synthetic metabolism: the acs and acr were used in two different efforts to mitigate carbon loss from photorespiration in the CBB cycle27,28, and the pk was used to enable the SACA pathway18.

To evaluate the feasibility of our hypothetical ReForm pathway, we carried out a stepwise construction of the pathway by sequentially adding each purified enzyme to a buffer containing a labeled 13C-isotope of formate and necessary cofactors. High-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) analysis of all three CoA-thioesters demonstrated that the initial sequence of the pathway was functional, but we did not observe the production of acetyl-CoA from the complete pathway (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 5). The acyl-CoA reductase (acr) from R. palustris was previously shown to catalyze the unwanted reduction of acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde29, and when tested, we observed promiscuous activity on acetyl-CoA as a substrate (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that the acr was preventing acetyl-CoA detection.

Because we envisioned the ultimate use of ReForm is the production of an end product downstream of acetyl-CoA, and to help pull the pathway forward thermodynamically, we added an additional biosynthetic step to produce malate via a malate synthase (mls) from E. coli15. While we were able to detect small quantities of malate (~1 µM; Supplementary Fig. 7), the selected enzymes’ low activities with nonnative substrates presented a major bottleneck. Furthermore, these results demonstrate that, rather than a simple refactoring of previous designer metabolic pathways or repurposing natural enzymes, engineered enzymes would be required to implement ReForm.

Engineering a phosphoketolase into an acetyl-Pi synthase

To improve the titer and rate of our pathway, we sought to engineer the enzymes of ReForm. Our general strategy was to search for homologous enzymes that have high promiscuity toward the desired reactions and then apply directed evolution principles to engineer the enzymes for greater activities with the nonnative substrates. A key feature of our approach was the use of cell-free gene expression (CFE) systems for the rapid synthesis and functional testing of both protein homologs and mutants30,31,32,33. We demonstrated this approach by carrying out four enzyme engineering campaigns.

We first targeted the phosphoketolase reaction for producing acetyl-Pi (Fig. 2a), given previously reported low native activity for this reaction (Bado Pk, ~0.005 µM min−1 mg−1)18,34. We constructed a curated phylogenetic tree of the entire annotated pk protein family (IPR005593, composed of ~15,000 members; Supplementary Fig. 8), of which we randomly selected a set of 30 homologs based on evolutionary diversity to express, purify and test for activity with glycolaldehyde (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 9).

a, The native phosphorolytic cleavage activity of pk to produce acetyl-Pi resembles the target engineered reaction. b, Exploring a diverse set of homologs resulted in several enzymes with activity for glycolaldehyde, including a higher activity than our initial candidate B. ado (colored in red). Organisms that are colored gray were removed from the analysis as they were insoluble or low yielding when expressed in E. coli (Supplementary Fig. 9). Percent conversion was determined by quantification of CoA and acetyl-CoA (mean of n = 3, error bars indicate ±s.d.) through coupling the pk with a pta (Supplementary Fig. 9). Complete list of species names can be found in Supplementary Table 3. c, A schematic of the cell-free protein engineering workflow. Site saturation mutagenesis and cell-free protein expression are carried out in less than 24 h to generate sequence-defined libraries. LET, linear expression template. d, ISM of 16 residues of Csac Pk (‘WT backbone’) showing percent conversion normalized to the step backbone (colored white; n = 1). After further characterization, four substitutions (H58W, H132S, I479V and S523N; asterisks) were identified and resulted in a quadruple mutant. e, HPLC traces of acetyl-CoA product (red) and CoA substrate (purple) of wild-type (WT) pk and engineered mutants. Traces are single samples representative of n = 3 independent experiments. 100% yield refers to the complete conversion of CoA into acetyl-CoA, or 0.5 mM of acetyl-CoA (mean of n = 3, error bars indicate ±s.d.). f, Electron density map and model of Csac M4 complexed with Ac-TPP at a global resolution of 2.30 Å (PDB: 9CD4). g, Model of the active site of Csac M4 complexed with TPP (PDB: 9CD3) and Ac-TPP (PDB: 9CD4) overlaid with their respective electron density map of the cofactor.

We identified several homologs with a higher activity than our initial candidate enzyme from literature, notably one (Csac Pk) with an approximately tenfold increase under the tested in vitro reaction conditions. Based on structural considerations (that is, 6 Å around the carbanion of the thiamine diphosphate cofactor ylide), evolutionary conservation (that is, an EVmutation probability density model trained on a multiple sequence alignment of evolutionarily related sequences)35 and a deep learning model trained to optimize local amino acid microenvironments36, we initially selected the top 16 residues with potential importance for catalysis and substrate specificity to mutate (Fig. 2c). We used iterative site saturation mutagenesis (ISM) to identify and accumulate beneficial mutations of these residues for acetyl-Pi synthesis (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). Each round, residue positions that had low tolerance to mutations (for example, only the wild-type amino acid displayed nonzero activity) were replaced with new residues beyond the initial 16—selected on the basis of the same initial considerations—to survey a larger sequence space. A key feature of our cell-free ISM approach is that we collect sequence-fitness data for a given residue with all amino acid changes, allowing us to pick the highest-performing mutation. After three rounds of ISM and exploring 1,200 unique, sequence-defined mutants among 37 residues, we obtained a quadruple mutant (Csac M4) with a more than tenfold increase in catalytic efficiency compared with wild-type (kcat/KM increase from 0.085 ± 0.016 to 1.18 ± 0.17 mM−1 min−1, respectively) (Fig. 2d,e and Supplementary Fig. 12). One residue found in Csac M4 (H132) was previously found to confer enhanced activity toward glycolaldehyde when mutated to an asparagine in Bado Pk. Our results confirm that H132N enhances activity in Csac Pk, but the optimal mutation at this residue was found to be H132S34 (Supplementary Fig. 11).

To gain insights into the topology of the engineered enzyme’s active site, we solved the structure of Csac M4 at a resolution of 2.30 Å with cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). Soaking the enzyme with glycolaldehyde without the addition of phosphate as the resolving nucleophile enabled us to gain a glimpse of the reaction mechanism by covalently trapping glycolaldehyde on thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP) (Fig. 2g). This reaction intermediate, 2-acetyl-TPP (Ac-TPP) is shared between the canonical reaction mechanism and the engineered enzyme, enabling the switch in catalysis from phosphorolytic cleavage of sugars to the phosphorylation and dehydration of glycolaldehyde18,37. Observing the Ac-TPP cofactor provides insight into the nonnative reactivity with glycolaldehyde and could help guide future pk engineering efforts for sustainability applications34.

Divergent directed evolution of substrate-specific acyl-CoA reductases

After having success with our phosphoketolase engineering campaign, we next targeted the two acyl-CoA reductase reactions of ReForm. Engineering acr presented a unique challenge in that we needed to decrease activity with acetyl-CoA while simultaneously improving activity for formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA (Fig. 3a), a feat that could be difficult to achieve in cells given endogenous acetyl-CoA levels. To help control specificity, our approach was to engineer two distinct enzymes to catalyze these respective reductions instead of a single enzyme with selectivity for both substrates. We randomly selected a diverse set of 34 candidates from among three protein families with reported acylating dehydrogenase activity (IPR013357, IPR012408 and IPR00361; Supplementary Fig. 15) to express and characterize (Supplementary Fig. 16). Serendipitously, we identified a single acr with high activity for both formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA from the anaerobic photoautotrophic bacteria Chloroherpeton thalassium that surpassed the activity of our initial enzyme (Rpal Acr28) by approximately twofold (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Figs. 16c and 17). However, this increase in activity for our two desired substrates was concomitant with an increase in reactivity toward acetyl-CoA (Supplementary Fig. 17c).

a, The broad substrate tolerance of acr results in an enzyme that catalyzes both desired reactions in ReForm and an unwanted reaction with acetyl-CoA. b, Exploring the substrate promiscuity of diverse homologs resulted in an enzyme with increased activity for both formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA. The rate was determined by measuring a decrease in NADH absorbance as the reaction proceeded (mean of n = 3, error bars indicate ±s.d.) and then normalized to Rpal Acr. S. rub, Serratia rubidaea; V. aer, Vibrio aerogenes; C. tha, Chloroherpeton thalassium; L. mon, Listeria monocytogenes; R. pal, Rhodopseudomonas palustris. c, ISM of 16 residues showing reaction rate normalized to wild type (WT) (colored white; n = 1). Mutations that were identified to either increase or retain activity with formyl-CoA or glycolyl-CoA and decrease activity with acetyl-CoA are marked with asterisks. d, Further characterization of the specificity of hits identified in ISM (mean of n = 3, error bars indicate ±s.d.). e, After the first round of ISM, different beneficial mutations were found for formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA, resulting in the engineering campaign splitting into two paths.

To decrease activity toward acetyl-CoA, we tested a 16-residue, site-saturated library of Ctha Acr mutants against all three CoA-thioesters. The goal was to find mutations that selectively increased activity for formyl-CoA or glycolyl-CoA and/or decreased activity for acetyl-CoA. We screened residues surrounding the CoA-thioester binding pocket (a total of 915 unique substrate–mutant pair reactions) by individually supplying formate, glycolate or acetate along with Enap Acs (in situ producing a CoA-thioester) and measuring NADH oxidation from each acr mutant (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 18a–d). We identified multiple residues that imparted control over substrate specificity, with residues for formyl-CoA (I251, A253 and L417) and glycolyl-CoA (S119 and T120) surprisingly sharing little in common (Fig. 3d). For example, L417F increased specificity as well as activity. We focused on mutations that provided conditional orthogonality (that is, mutations that increased activity for formyl-CoA but not glycolyl-CoA), moving forward with those that imparted control over substrate specificity (that is, rate of desired reaction over rate of reaction on acetyl-CoA; Supplementary Fig. 18e–h). After fixing different beneficial mutations, additional rounds of ISM focused on a downselected set of eight residues identified in the first round that seemed to most impact substrate preference (Supplementary Fig. 19 and 20), which led to a bifurcation in the evolution paths of mutagenesis (Fig. 3e).

We performed multiple rounds of ISM for a formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA specific acr separately, resulting in an acrf triple mutant (Cthalf M3; Fig. 4a) with a 15-fold increase in specificity for formyl-CoA (Supplementary Fig. 21) and an acrg double mutant (Cthalg M2; Fig. 4b) with a 13-fold increase in specificity for glycolyl-CoA (Supplementary Fig. 21). While all mutations are found in the substrate binding pocket, the final mutants have no mutated residues in common (Supplementary Fig. 22). When comparing these mutations with earlier work that similarly engineered Rpal Acr to increase specificity toward glycolyl-CoA28, we found that there are two shared residues in common upon alignment of the two sequences. For example, Cthalg M2 contained mutation T250V, analogous to the Rpal Acr L326I. An additional mutation in Rpal Acr, V329T, is found only in our formyl-CoA reductase, A253S. These data point to complex epistatic interactions within the active sites of these acyl-CoA reductases that are difficult to navigate for increases in specificity over the native reaction. They further highlight the need for high-throughput CFE methods for navigating sequence–function landscapes as we have observed before38 but uniquely show here for tuning substrate specificity.

a–c, Enzyme engineering campaigns and characterized mutants for the formyl-CoA reductase (a), glycolyl-CoA reductase (b) and acyl-CoA synthetase (c) reactions. The mutant showing the best parameters that was carried forward in each round is highlighted. Campaigns resulted in remodeled active sites to accept nonnative substrates, with the residues that were mutated labeled on protein structures for each. All values are either from n = 3 independent measurements or are results from Michaelis–Menten fitting from n = 3 independent experiments (error bars indicate ±s.d.). Complete engineering campaigns can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Engineering a formyl-CoA synthetase

Our final enzyme engineering challenge was the initial acyl-CoA synthetase reaction that activates formate—a reaction historically difficult to engineer owing to these enzymes’ native activity with, and the high cellular abundance of, acetate20. Given that formate would be exogenously supplied to the reaction in saturating quantities, we focused on improving the turnover number (kcat) of acs. Our starting point was an acetate-activating acs from Erythrobacter sp. NAP1, which was previously engineered to change its native substrate specificity to glycolate, highlighting its engineerability27. Exploring 18 residues over four rounds of ISM resulted in a quadruple mutant (Enap M4) with a twofold increase in kcat for formate (Supplementary Figs. 23–25). All four accumulated mutations were in the putative substrate binding pocket and fill in the active site with bulky, hydrophobic amino acids (Supplementary Fig. 26). Comparison of Enap M4 with the previously engineered variant for glycolate activation indicated a shared mutated residue at position 379. Interestingly, a V379A substitution was beneficial for opening the active site for glycolate, which supports the hypothesis that a V379I substitution closes in the active site for the slightly smaller formate27. Further expression of acs in a strain of E. coli with a genomic knockout of a lysine acetyltransferase that posttranslationally inactivates acs in vivo further increased kcat by another fivefold, resulting in a tenfold overall increase in activity27,39 (2.5 ± 0.3 to 25 ± 1.7 s−1; Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 25). While we did not observe a significant shift in KM throughout the engineering campaign, the measured values do fall in similar ranges to naturally found formate-activating enzymes (for example, formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase40), indicating we may have reached the inherent natural limit to formate affinity given its low molecular mass and low hydrophobicity41.

ReForm pathway optimization

Our comprehensive ISM campaigns assessed 3,173 sequence-defined enzyme variants to develop four engineered enzymes required for ReForm (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 27). To increase titers (Supplementary Fig. 28), we carried out an optimization of the pathway in three steps. First, we tuned cofactor and enzyme loading with definitive screening design (DSD; Supplementary Fig. 29). The objective was to increase malate titers given a range of possible cofactor and enzyme concentrations. We restricted maximum values of all components to prevent superior conditions resulting simply from increased enzyme loading (enzyme concentrations were capped between 1 μM and 20 µM). Second, we added cofactor regeneration to recycle cofactors and keep concentrations high (Supplementary Fig. 30). A formate dehydrogenase was added to regenerate NADH from formate while a polyphosphate kinase and polyphosphate were added to regenerate ATP42. Recycling free CoA occurs at the final reaction of the pathway to produce malate; optimization of CoA recycling should be evaluated in the context of the downstream reaction pathway from acetyl-CoA. Third, we added a formyl-phosphate reductase (fpr) to recycle formyl-phosphate that could be produced from an unwanted side reaction between formyl-CoA and the phosphotransacetylase into formaldehyde21 (Supplementary Fig. 31). When combined, ReForm pathway titers increased by three orders of magnitude over our original pathway iteration (Supplementary Fig. 32). We also measured the three CoA-thioester intermediates to gain information on pathway function and identify rate-limiting steps in the pathway (Supplementary Fig. 32). Interestingly, we observed a spike of formyl-CoA production within the first 30 min, closely followed by glycolyl-CoA. As malate production did not reach a steady state until 2 h, these data point to a potential bottleneck at the phosphoketolase reaction.

ReForm assimilates diverse C1 substrates in a modular fashion

We next attempted to demonstrate the modularity of the ReForm architecture with diverse C1 substrates (Fig. 5a). First, we focused on using formate that was a direct product of the electrochemical reduction of CO2 as a substrate. Formate was produced using a commercial SnO2 inorganic catalyst in an electrochemical module at a rate of 150 mM h−1 per milligram of catalyst. Within 20 min, 50 mM formate was synthesized in isolation as a pure product, which was confirmed by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Supplementary Fig. 33). In other words, impurities were not observed. Then, this formate was combined with the enzymes, cofactors and buffers of ReForm. We observed 606 ± 23 µM of malate produced from 8 mM of crude electrochemically derived formate at 24 h (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 34).

a, The combined chemoenzymatic cascade enables the assimilation of C1 substrates (formate, CO2, formaldehyde and methanol) into acetyl-CoA. Malate synthase (mls) is added to convert acetyl-CoA into malate. Formate and CO2 can be assimilated through the reductive branch of ReForm, while formaldehyde and methanol can be assimilated through the oxidative branch. b–d, Time course of malate synthesis with formate derived from the electrochemical reduction of CO2 (b), formaldehyde (c) and methanol (d) as substrates. The black data point indicates the maximum observed malate titer for each substrate. Malate concentration was determined by liquid chromatography–MS with an m/z [M − H]− of 133.01 for 12C-malate (CO2, formaldehyde and methanol as substrates) and 135.01 for the malate containing two 13C from 13C-formate (formate as a substrate) (mean of n = 3, error bars indicate ±s.d.).

Second, we asked how robust ReForm was to the assimilation of other C1 substrates. We therefore designed alternative routes through ReForm to convert both formaldehyde and methanol into acetyl-CoA with no changes to the core architecture of the pathway except for simply removing the first enzymatic step (acs; Fig. 5a). Notably, these two variations are cofactor neutral (that is, there is no net theoretical change in reducing equivalents or ATP per molecule of acetyl-CoA produced) unlike the pathway from formate. Following pathway optimization (Supplementary Fig. 35), we were able to produce malate from formaldehyde (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 36) and methanol (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 37). Interestingly, CoA-thioester intermediate profiles over time differ when changing C1 substrates (Supplementary Figs. 32 and 36). This phenomenon could be due to the high concentration of NADH needed to push the pathway forward from formate, while the formaldehyde variation relies on acr’s reversibility governed by the NADH:NAD+ ratio and a high starting concentration of NAD+. The tradeoff of utilizing methanol and formaldehyde as substrates is that, while possessing a higher thermodynamic driving force than formate, an additional source of electrons is needed to provide reducing power for reactions beyond acetyl-CoA that require them, whereas formate can provide reducing power through the addition of a formate dehydrogenase. Taken together, our results highlight the modularity of the ReForm architecture, showing flexibility for bioconversion applications.

Discussion

In this work, we demonstrated a synthetic chemoenzymatic cascade in vitro called ReForm toward the valorization of organic C1 substrates. To build ReForm, we developed and implemented a rapid cell-free protein synthesis pipeline to engineer four enzymes by testing 3,173 sequence-defined mutants derived from 66 enzyme candidates from both eukaryotic and prokaryotic origins. Through extensive enzyme discovery, engineering and pathway optimization, we were able to improve pathway titers from formate through acetyl-CoA toward the end product malate by several orders of magnitude. Moreover, we showed the ability to use formate from electrochemically reduced CO2 as a carbon source. While each C1 feedstock has distinct advantages—such as methanol’s higher energy density and formate’s lower toxicity—the modularity of ReForm could enable their interchangeable or combined use, depending on the application context.

A rise in designer synthetic pathways15,16,17,18,19,20,21,43 has inspired pathways like ReForm. For example, the FORCE pathway17 and the SACA pathway18 have achieved high product titers using formaldehyde as a substrate. Simple refactoring of these pathways to use new substrates often achieves little success without further engineering efforts16. With respect to formate assimilation, extending the pathway to formate has remained difficult with acyl-CoA reductases owing to specificity challenges. Here, using CFE, we were able to bypass cellular constraints and carry out four extensive enzyme engineering campaigns targeting activity and specificity to build the complete pathway. ReForm takes an important step toward building completely new-to-nature pathways as five out of the six steps required engineered enzymes, compared with state-of-the art pathways that are often built around only one to two engineered enzymes with many natural enzymes (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Consisting of only six reactions, ReForm requires a lower total enzyme loading to achieve higher potential specific titers compared with longer synthetic pathways (~4 mg ml−1 total loading; less than half of the state-of-the-art in vitro synthetic pathway THETA)16. The metabolic energy efficiency of ReForm (only 4 ATP and 2 NADH equivalents per acetyl-CoA compared with 7 ATP and 4 NAD(P)H of the Calvin cycle and 4 ATP and 5 NAD(P)H of the THETA cycle; Supplementary Fig. 38) helps to enable similar titers of acetyl-CoA to be achieved while operating at these lower loadings16,44 (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, this energy balance does not account for the input required for electrochemical reduction of CO2 in ReForm. While excelling in specific titers and reaction longevity as compared with the THETA and CETCH cycles44, ReForm has lower peak productivities (Supplementary Table 1). This tradeoff is probably caused by the relatively low reaction rates of the engineered enzymes, which compound when assembled into the entire pathway. However, the electrochemical production of formate additionally provides the dual advantage of carbon coming from CO2 and electrons coming from electricity, eliminating the need for a sacrificial substrate to provide reducing power while avoiding rate-limiting enzymatic CO2-fixing steps as seen in some synthetic pathways.

A feature of our work was that the discovery efforts led to understanding (for example, residues determining acr specificity, cryo-EM structure of pk capturing the reaction intermediate), which could drive sustainability applications in the future. Indeed, we anticipate that ReForm will facilitate efforts to build and improve synthetic C1 utilization pathways for a formate-based bioeconomy, both in cells and in in vitro cascades. The linear nature and minimal overlap with central metabolism of ReForm may simplify its implementation into living cells16. However, interference of the engineered enzymes with a cell’s existing metabolism and the limited availability of necessary cofactors (for example, a high ratio of NADH:NAD+ is needed to drive the pathway forward) present challenges. The residual side reactivity of engineered acyl-CoA reductases with acetyl-CoA, while small, provides an area for further engineering. The recently proposed and engineered formyl-phosphate reduction route to produce formaldehyde from formate may be a tenable solution to overcome this challenge when integrated with ReForm; however, current rates of these enzymes are too low (kcat = 0.12 s−1)21. We anticipate that rigorous pathway design, modeling and iterative engineering would be required for in vivo implementation of ReForm, as was the case for the reductive glycine pathway10 and the synthetic methanol assimilation pathway45.

In vitro enzymatic cascades are beginning to show promise for sustainable production of value-added chemicals46. ReForm could similarly be implemented in vitro, but further innovations in areas such as cofactor costs and stability would need to be implemented. The use of noncanonical cofactors, such as replacing NADH with the cheaper nicotinamide mononucleotide, holds promise as one approach with a systematic engineering framework discovered to change reducing equivalent preferences of natural enzymes47. New evidence also indicates the possibility of the enzymatic reduction of carboxylic acids to aldehydes without activation by ATP and CoA, which could lead to an ATP-free carbon assimilation pathway48. In both cells and cell-free systems, improvements in volumetric productivities (g product l−1 h−1), reaction longevity and total turnover per catalyst will be required for commercial production.

By combining electrochemistry and synthetic biology, the ReForm pathway expands the possible solution space of generalizable CO2-fixation strategies. While existing biological strategies have been impactful on their own49,50, we anticipate that hybrid biological and chemical technologies will become critically important for a carbon and energy efficient future.

Methods

Materials and bacterial strains

All consumables were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich unless stated otherwise. Standard microtiter plates (96- and 384-well) were purchased from BioRad. 13C-sodium formate was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories. DNA for all enzymes used was ordered from Twist Bioscience in the vectors pJL1 (Addgene #69496) for expression via CFE or pETBCS, a modified pET-22b vector51 (Novagen/EMD Millipore) for recombinant expression in E. coli. Codon optimization for E. coli was either performed using Integrated DNA Technologies or Twist Bioscience. NEB 5-alpha chemically competent E. coli cells were used for cloning (NEB), BL21 Star (DE3) (Invitrogen) cells were used for cell-free lysate production and BL21 (DE3) chemically competent cells (NEB) were used for recombinant expression of proteins. For the expression of acyl-CoA synthetases, an E. coli BL21 (DE3) patZ knockout was created using a CRISPR–Cas9 and λ-red recombination-based method52,53. In brief, the CRISPR endonuclease introduces a double-stranded DNA break in a locus of interest. Provided with a donor DNA that is homologous to sections of the chromosome on 5′ and 3′ ends but lacks the knockout gene, λ-red proteins will recombine the donor DNA into the chromosome. This simultaneously removes the gene of interest and the site where the DNA break is occurring, allowing the cells to survive if the knockout was successful. To confirm the knockout of patZ, single colonies were picked and analyzed by colony polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers flanking the gene.

Cell-free protein synthesis and enzyme engineering

Crude cell extracts were prepared as previously described using E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) cells (Invitrogen)54. CFE reactions were performed on the basis of the Cytomim system55,56 and, unless otherwise noted, carried out in 96-well or 384-well PCR plates (Bio-Rad) as 15-µl reactions with 1 µl of linear expression template (LET) serving as the DNA template. In brief, 15-μl reactions were carried out with final concentrations of 8 mM magnesium glutamate, 10 mM ammonium glutamate, 130 mM potassium glutamate, 1.2 mM ATP, 0.85 mM of GTP, CTP and UTP each, 0.03 mg ml−1 folinic acid, 0.17 mg ml−1 tRNA (Roche), 0.4 mM NAD+, 0.27 mM CoA, 4 mM oxalic acid, 1 mM putrescine, 1.5 mM spermidine, 57 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 33 mM phosphoenolpyruvate (Roche), 30% v/v cell extract and the remaining volume with water to 15 μl. Reactions were incubated at 30 °C for 16–20 h.

Cell-free site saturation mutagenesis was performed as described previously38. In brief, primers were designed using Benchling with melting temperature calculated by the default SantaLucia 1998 algorithm. The general heuristics we followed for primer design were a reverse primer of 58 °C, a forward primer of 62 °C and a homologous overlap of approximately 45 °C. All primers were ordered from Integrated DNA Technologies; forward primers were synthesized in 384-well plates normalized to 2 µM for ease of setting up reactions. All cloning steps were set up using an Integra VIAFLO liquid handling robot in 384-well PCR plates (Bio-Rad). The cell-free library generation was performed as follows: (1) the first PCR was performed in a 10-µl reaction with 1 ng of plasmid template added, (2) 1 µl of DpnI (NEB) was added and incubated at 37 °C for 2 h, (3) the PCR was diluted 1:4 by the addition of 29 µl of nuclease-free water, (4) 1 µl of diluted DNA was added to a 3-µl Gibson assembly reaction and incubated for 50 °C for 1 h, (5) the assembly reaction was diluted 1:10 by the addition of 36 µl of nuclease-free water, and (6) 1 µl of the diluted assembly reaction was added to a 9-µl PCR reaction. All PCR reactions used Q5 Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB). The product of the second PCR is a LET for expression in CFE, which are amplified using universal forward (CTGAGATACCTACAGCGTGAGC) and reverse (CGTCACTCATGGTGATTTCTCACTTG) primers. To accumulate mutations for ISM, 3 µl of the round ‘winner’ from the diluted Gibson assembly plate was transformed into 20 µl of chemically competent E. coli (NEB 5-alpha cells). Cells were plated onto lysogeny broth (LB) plates containing 50 µg ml−1 kanamycin (LB-Kan). A single colony was used to inoculate a 50-ml overnight culture of LB-Kan, grown at 37 °C with 250 rpm shaking. The plasmid was purified using ZymoPURE II Midiprep kits (Zymo Research) and sequence confirmed.

Cryo-EM sample preparation and data collection

Csac Pk M4 was purified as described below. The protein was then additionally purified to homogeneity using a Cytiva HiPrep Sephacryl S-200 HR Column according to the manufacturer’s specifications with a running buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl and 250 µM MgCl2. After purification, TPP was added to a final concentration of 50 µM. To covalently trap glycolaldehyde on TPP, 1 mg ml−1 of purified protein was soaked in 25 mM glycolaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, and then the buffer was exchanged into the running buffer using Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filters (50 kDa MWCO; EMD Millipore).

Ultrafoil 1.2/1.3 Au 300 mesh grids were glow discharged, and 3 μl of the protein sample at 1 mg ml−1 was applied to the grid surface. The grids were incubated for 5 s in the humidity chamber of Vitrobot Mark IV set at 100% humidity and 4 °C. Grids were blotted at blot force 2 for 3 s and quickly plunge frozen in liquid ethane. Cryo-EM imaging was performed on a ThermoFisher Titan Krios equipped with Falcon 4i direct electron detector and SelectrisX post-column energy filter. The microscope was operated at 300 kV accelerating voltage with a nominal magnification of ×130,000, which resulted in a magnified pixel size of 0.98 A. Each movie was recorded at the total electron dose of 40 e− Å−2 over 38 frames. The images were obtained at a defocus ranging from −0.8 to −1.8 μm.

Image processing and 3D reconstruction

Preprocessing of both datasets was performed using cryoSPARC57. Dose-fractionated movies were subjected to beam-induced motion correction and dose weighting using patch motion correction. Contrast transfer function parameters were performed for each motion-corrected micrograph followed by micrograph curation based on parameters such as average intensity and contrast transfer function fit resolution. A total of 3,159,785 particles were extracted from 5,900 micrographs for the Csac Pk M4-TPP, and 3,761,029 particles were extracted from 6,652 micrographs for the Csac Pk M4-HDE/HTL dataset. Subsequently, three to five rounds of two-dimensional classification were performed, followed by multiclass ab initio and heterogeneous refinement. Homogeneous refinement was performed on the largest class from the heterogeneous refinement job on the binned particles. Furthermore, the particles were reextracted to 0.95 Å per pixel, and another round of homogeneous refinement was performed. UCSF ChimeraX (v.1.7)58 was used for map and model visualization.

Molecular model building

AlphaFold2 was used to generate a model dimer of Csac Pk M4 using its protein sequence59. The X-ray crystal structure of phosphoketolase from Bifidobacterium breve complexed with TPP/HDE/HTL (PDB: 3ahc, 3ahe and 3ahd)60 was used to align with the AlphaFold model to roughly estimate the position of ligand in the maps. The ligands were combined with the AphaFold-generated dimer model and were fit into the maps using the ChimeraX ‘fit-in-map’ function. To improve the modeling, several rounds of interactive model adjustment in Coot (v0.9.8.8 EL) followed by real-space refinement of the fit model were performed in Phenix (v 1.21.1-5286) from SbGrid suite61 using secondary structure restraints in addition to default restraints. The final model was generated using Phenix refinement.

ReForm assays

All reactions were performed at 30 °C with the reaction size noted below. All reactions were quenched by addition of 5 µl 10% w/v formic acid to 20 µl of sample (or 3.75 µl 10% w/v formic acid to 15 µl of sample), centrifuged at 4,000g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove precipitated protein, and either immediately prepared for analysis or stored at −80 °C until needed. To prepare for MS analysis of CoA-thioesters and malate, 20 µl of quenched reaction was transferred to a clean vial and diluted 1:2 with 20 µl of H2O.

Stepwise pathway construction

Final reactions contained 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 5 mM ATP, 6.5 mM NADH, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM CoA, 50 µM TPP, 1 mM glyoxylate, 50 mM 13C-sodium formate, 5 U ml−1 pyrophosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich I5907), 3 µM Enap Acs, 3 µM Rpal PduP, 10 µM Mext Oxc M4, 10 µM Bado Pk, 0.25 µM Ecol Pta and 1 µM Ecol Mls. A reagent mix was first made with all components except for the core ReForm enzymes and distributed into seven 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Enzymes were added to the final concentrations listed above with each sequential reaction containing an additional enzyme. Extra H2O was added to adjust the final reaction volume to 200 µl. A negative control containing only H2O and no additional enzyme was also included. These reactions were sampled for both CoA-thioesters and malate. Then, 20-µl samples were taken at various time intervals (10, 30, 60, 90, 120, 150, 180 and 240 min) to ensure that no time-resolved production of intermediates or malate was missed.

Initial unsuccessful pathway attempts (that produced detectable formyl-CoA and glycolyl-CoA but no detectable acetyl-CoA or malate) utilized lower concentrations of Bado Pk (5 µM) and Mext Oxc M4 (5 µM), lower concentrations of Enap Acs and Rpal PduP (1 µM each) and higher concentrations of Ecol Pta (1 µM). Pta was decreased after observing potential side reactivity with formyl-CoA (an observed decrease in formyl-CoA after the direct addition of pta).

Pathway assessment when leaving one enzyme out

Reactions were set up as described for the stepwise pathway construction except for the decrease of Ecol Pta from 0.25 µM to 0.125 µM. A reagent mix was first made with all components except for the core ReForm enzymes and formate and distributed into eight 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Each reaction had a single enzyme removed (or formate) with extra volume of H2O added to bring up the final reaction volume to 90 µl. Then, 20-µl samples were taken at various time intervals (60, 120, 180 and 240 min) to ensure that no time-resolved production of intermediates or malate was missed.

DSD to improve pathway activity

The three-level definitive screening design (DSD) was performed using JMP Pro 17, with upper and lower limits and the reaction components varied found in Supplementary Fig. 29. All engineered variants of enzymes were used in this experiment. We first performed a screen of 21 reaction conditions to map out the relationship between all tested variables and malate production. Final reactions contained 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 2 mM ATP, 4 mM NADH, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 µM TPP, 1 mM glyoxylate, 50 mM 13C-sodium formate, 5 U ml−1 pyrophosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich I5907) and 0.5 µM Ecol Mls. The concentrations of remaining enzymes and CoA varied between each reaction condition. A reagent mix was first made with all components except for the varied enzymes and CoA and distributed into a 96-well PCR plate. Different dilutions of each varied component were added to the reactions to bring up the total volume to 15 µl, with each condition run in triplicate for 4 h. With the resulting data, three regression models were fit with default variables: stepwise, stepwise (exclusive to nonzero data points) and support vector machines (SVMs). All models were fit using default parameters that modeled only first-order interactions between variables. For stepwise models, a minimum Bayesian information criterion (BIC) stopping rule was used. To determine predicted optimized conditions, the prediction profiler was set to maximize desirability. We then went on to validate predictions by comparing the best condition that was observed in the screen with the three predicted conditions. The stepwise prediction set everything to the upper bound of the DSD screen (acrf = formyl-CoA specific acr; acrg = glycolyl-CoA specific acr): 1 mM CoA, 2 µM acs, 5 µM acrf, 5 µM acrg, 20 µM oxc, 20 µM pk and 0.01 µM pta. The stepwise (nonzero) prediction was identical, except that oxc was set to the lower bound of the DSD screen (2 µM). The SVM prediction had 0.94 mM CoA, 1.18 µM acs, 3.63 µM acrf, 3.66 µM acrg, 14.27 µM oxc, 20 µM pk and 0.43 µM pta. These reactions were set up identically to the DSD screen.

After optimizing the pathway for malate production from formate, we repeated DSD with the variant of ReForm that uses formaldehyde as a substrate. As above, all engineered enzymes were used in this experiment and the reaction components varied can be found in Supplementary Fig. 35. We first performed a screen of 21 reaction conditions to map out the relationship between all tested variables and malate production. Final reactions contained 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 µM TPP, 1 mM glyoxylate, 50 mM formaldehyde and 0.5 µM Ecol Mls. The concentrations of remaining enzymes, CoA and NAD+ varied between each reaction condition. Three models were then fit as described above; however, because there was no measured zero-malate condition, we included only a single stepwise model. The stepwise optimized conditions were 0.2 mM CoA, 0.5 mM NAD+, 5 µM acrf, 5 µM acrg, 2 µM oxc, 20 µM pk and 0.01 µM pta. The SVM-optimized conditions were 0.78 mM CoA, 2.19 mM NAD+, 5 µM acrf, 5 µM acrg, 15.5 µM oxc, 20 µM pk and 0.384 µM pta. These reactions were set up identically to the DSD screen, and an additional experiment was run using 20 mM formaldehyde to examine potential inhibitory effects.

Cofactor regeneration to improve pathway activity

Using the DSD-optimized conditions with formate as a substrate, we then added cofactor regeneration enzymes for ATP and NADH. Final reaction conditions were the same as above with two additional polyphosphate kinases (Rmel ppk1 and Ajoh ppk2) added at 0.4 or 2 µM and an additional formate dehydrogenase (P101 fdh) added at 1 or 6 µM. Polyphosphate (adjusted to pH 7 with KOH) was added at a final concentration of 10 mM (phosphate equivalents), and 13C-sodium formate was increased to 100 mM. Reactions were performed in triplicate at 15 µl and incubated for 4 h.

Metabolic proofreading to improve pathway activity

After determining cofactor regeneration enzyme conditions, we wanted to test whether adding in a recently engineered formyl-phosphate reductase (fpr), DaArgC3, could improve pathway activity21. Earlier experiments suggested that pta could be exhibiting potential side activity with formyl-CoA and producing formyl-Pi, a dead-end metabolite for ReForm. We hypothesized that adding in fpr could reduce the produced formyl-Pi into formaldehyde to introduce the wasted metabolite back into the pathway. Using the conditions from the cofactor regeneration screen (2 µM of ppk1 and ppk2 and 1 µM of fdh) as the base reaction, we added 0.5, 1 or 5 µM of fpr. Reactions were performed in triplicate at 15 µl and incubated for 4 h.

Reform pathway assessment with time using different C1 substrates

The metabolic proofreading strategy did not provide any quantifiable benefit using fpr under the conditions tested, so we moved forward using the optimized DSD conditions (with cofactor regeneration for formate as a substrate) without fpr for further testing of ReForm. With formate as a substrate, final reaction conditions were 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 2 mM ATP, 4 mM NADH, 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CoA, 50 µM TPP, 2 mM glyoxylate, 100 mM 13C-sodium formate, 10 mM polyphosphate, 5 U ml−1 pyrophosphatase (Sigma-Aldrich I5907), 2 µM acs, 5 µM acrf, 5 µM acrg, 20 µM oxc, 20 µM pk, 0.01 µM pta, 0.5 µM mls, 2 µM ppk1, 2 µM ppk2 and 1 µM fdh. The same conditions were used with formate derived electrochemically from CO2 as a substrate, except that a final concentration of 8 mM formate (12C) was used. Given that formate was produced electrochemically at a concentration of 42 mM, this accounted for ~20% v/v of the reaction. Specifically, formate was first produced in isolation using the electrochemical reduction catalyst. This formate was neutralized by the addition of HCl to a pH of 7. No additional purification or cleanup steps were performed; we refer to this as crude formate. This formate was then added to a separate reaction vessel containing necessary enzymes and cofactors.

With formaldehyde as a substrate, final reaction conditions were 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer pH 7.4, 2.19 mM NAD+, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.78 mM CoA, 50 µM TPP, 2 mM glyoxylate, 20 mM formaldehyde, 5 µM acrf, 5 µM acrg, 15.5 µM oxc, 20 µM pk, 0.384 µM pta and 0.5 µM mls. Reactions were performed in triplicate at 20 µl with time points as follows (hours): 0, 0.17, 0.33, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 6, 10, 18, 24, 36 and 48. The same reaction conditions were used with methanol as a substrate with the following exceptions. Final reactions additionally contained 300 U ml−1 catalase (Sigma-Aldrich C1345), 1 U ml−1 alcohol oxidase (Sigma-Aldrich A2404) and 20 mM methanol.

Calculation of pathway metrics

All rates (steady-state productivity, specific productivity and CO2 fixation rate) were calculated using the optimized ReForm pathway results shown in Fig. 4c, where formate is derived from the electrochemical reduction of CO2. Malate (and equivalently acetyl-CoA) synthesis rates can be optimistically calculated from the steady-state portion of the pathway between 0 h and 6 h (280 µM malate in 6-h yields) or more conservatively by taking the highest yield at 24 h (607 µM malate in 24 h). We additionally consider the spatially and temporally separate electrochemical module that reduces CO2 to formate, which ran for 1 h total (280 µM malate in 7 h yields 40.1 µM h−1 or 668 nM min−1 and 607 µM malate in 25 h yields 24.3 µM h−1 or 404 nM min−1). We report 40.1 µM h−1 as the steady-state productivity in Supplementary Table 1. The total enzyme loading for this reaction was 4.073 mg protein (Supplementary Table 9), which gives a specific productivity of 9.8 µM h−1 per milligram of protein. The specific productivity of CO2 equivalents assimilated was calculated using this value, taking into account that for every molecule of malate (or acetyl-CoA) produced, two molecules of CO2 equivalents (formate) are assimilated. We also include these values calculated for other state-of-the-art synthetic CO2-fixing pathways (the CETCH cycle and the THETA cycle). Quantitative comparison of these values can be difficult, but we believe it is important to holistically assess how each pathway functions, along with their inherent advantages and disadvantages.

Catalyst preparation and electrochemical reduction of CO2

All chemicals used for electrolytes, catalyst synthesis and electrode preparation, including iridium(III) chloride hydrate (IrCl3∙xH2O, 99.9%), tin (IV) oxide (SnO2, nanopowder, ≤100 nm) and potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, 99.7%), were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without any further treatments. Nafion 117 membrane and titanium felt were purchased from the Fuel Cell Store. In a typical procedure, 20 mg SnO2 and 60 μl Nafion perfluorinated resin solution were stirred and sonicated in 4 ml absolute ethanol to form the catalyst ink. Then, 4 ml of the ink was sprayed onto the gas diffusion layer (Freudenberg H23C3) with a SnO2 loading of 1 mg cm−2. All electrochemical experiments were performed in an MEA electrolyzer (SKU: 68732; Dioxide Materials), with a gasket to control the active area of 1 cm2 accessed with a serpentine channel, unless otherwise specified. A proton exchange membrane (Nafion 117) was sandwiched between the cathode and titanium felt-supported iridium oxide (IrO2/Ti) anode. The IrO2/Ti anode was fabricated according to a reported method62 with slight modifications. Unless otherwise specified, the anode was circulated with 0.5 M KHCO3 electrolyte at a rate of 10 ml min−1 with a peristaltic pump and with silicone Shore A50 tubing. Humidified CO2 was fed into the cathode at a rate of 40 sccm using an accurate mass flow controller. The cathodic product is collected in 10 ml of deionized water. The volume of anolyte used was 20 ml. Electrochemical measurements were carried out using an Autolab PGSTAT204 in an amperostatic mode and a current booster (10 A). Unless otherwise stated, at the end of 1 h of electrolysis, a sample of cathodic product and a sample of anolyte were extracted for liquid product analysis. Cathodic products and anolyte samples were identified by 1H NMR spectroscopy (600 MHz, Agilent DD2 NMR Spectrometer) using dimethyl sulfoxide as an internal standard and water suppression techniques.

Data collection and analysis

All statistical information provided in this Article is derived from n = 3 independent experiments unless otherwise noted in the text or figure legends. Error bars represent 1 standard deviation (s.d.) of the mean derived from these experiments. Data analysis and figure generation were conducted using Excel Version 2304, ChimeraX Version 1.5, GraphPad Prism Version 9.5.0 and Python 3.9. Data collected on the BioTek Synergy H1 Microplate Reader were analyzed using Gen5 Version 2.09.2.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available in the Article or its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. Atomic structures reported in this Article are deposited to the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 9CD3 and 9CD4. The cryo-EM data were deposited to the Electron Microscopy Data Bank under EMD-45461 and EMD-45462.

References

Lee, H. et al. in IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report (eds Core Writing Team, Lee, H. & Romero, J.) 35–155 (IPCC, 2023); https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/IPCC_AR6_SYR_FullVolume.pdf

Global Energy Review 2025 (IEA, 2025); https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025

Cai, W. et al. The 2024 China report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: launching a new low-carbon, healthy journey. Lancet Public Heal. 9, e1070–e1088 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Integrated electromicrobial conversion of CO2 to higher alcohols. Science 335, 1596–1596 (2012).

Bar-Even, A., Noor, E., Flamholz, A. & Milo, R. Design and analysis of metabolic pathways supporting formatotrophic growth for electricity-dependent cultivation of microbes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Bioenerg. 1827, 1039–1047 (2013).

Yishai, O., Lindner, S. N., Cruz, J. G., de la, Tenenboim, H. & Bar-Even, A. The formate bio-economy.Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 35, 1–9 (2016).

Bang, J. et al. Synthetic formatotrophs for one-carbon biorefinery. Adv. Sci. 8, 2100199 (2021).

Li, L. et al. Stable, active CO2 reduction to formate via redox-modulated stabilization of active sites. Nat. Commun. 12, 5223 (2021).

Crowther, G. J., Kosály, G. & Lidstrom, M. E. Formate as the main branch point for methylotrophic metabolism in Methylobacterium extorquens AM1. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5057–5062 (2008).

Kim, S. et al. Growth of E. coli on formate and methanol via the reductive glycine pathway. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 538–545 (2020).

Bang, J., Hwang, C. H., Ahn, J. H., Lee, J. A. & Lee, S. Y. Escherichia coli is engineered to grow on CO2 and formic acid. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1459–1463 (2020).

Claassens, N. J. et al. Replacing the Calvin cycle with the reductive glycine pathway in Cupriavidus necator. Metab. Eng. 62, 30–41 (2020).

Bar-Even, A. Formate assimilation: the metabolic architecture of natural and synthetic pathways. Biochemistry 55, 3851–3863 (2016).

Bar-Even, A., Noor, E., Lewis, N. E. & Milo, R. Design and analysis of synthetic carbon fixation pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 8889–8894 (2010).

Schwander, T., Borzyskowski, L. S. von, Burgener, S., Cortina, N. S. & Erb, T. J. A synthetic pathway for the fixation of carbon dioxide in vitro. Science 354, 900–904 (2016).

Luo, S. et al. Construction and modular implementation of the THETA cycle for synthetic CO2 fixation. Nat. Catal. 6, 1228–1240 (2023).

Chou, A., Lee, S. H., Zhu, F., Clomburg, J. M. & Gonzalez, R. An orthogonal metabolic framework for one-carbon utilization. Nat. Metab. 3, 1385–1399 (2021).

Lu, X. et al. Constructing a synthetic pathway for acetyl-coenzyme A from one-carbon through enzyme design. Nat. Commun. 10, 1378 (2019).

Siegel, J. B. et al. Computational protein design enables a novel one-carbon assimilation pathway. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 3704–3709 (2015).

Wang, J., Anderson, K., Yang, E., He, L. & Lidstrom, M. E. Enzyme engineering and in vivo testing of a formate reduction pathway. Synth. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1093/synbio/ysab020 (2021).

Nattermann, M. et al. Engineering a new-to-nature cascade for phosphate-dependent formate to formaldehyde conversion in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Commun. 14, 2682 (2023).

Hu, G. et al. Synergistic metabolism of glucose and formate increases the yield of short-chain organic acids in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 11, 135–143 (2022).

Lee, S. Y. et al. A comprehensive metabolic map for production of bio-based chemicals. Nat. Catal. 2, 18–33 (2019).

Sodium Malate Market Size By Grade (Pharmaceutical Grade, Food Grade, Industrial Grade), By Form (Powdered, Liquid, Granular), By Application (Food & Beverages, Pharmaceuticals, Personal Care & Cosmetics, Industrial Applications) & Forecast 2023–2032 (GMI, 2022); https://www.gminsights.com/industry-analysis/sodium-malate-market

Chou, A., Clomburg, J. M., Qian, S. & Gonzalez, R. 2-Hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase catalyzes acyloin condensation for one-carbon bioconversion. Nat. Chem. Biol. 15, 900–906 (2019).

Nattermann, M. et al. Engineering a highly efficient carboligase for synthetic one-carbon metabolism. ACS Catal. https://doi.org/10.1021/acscatal.1c01237 (2021).

Scheffen, M. et al. A new-to-nature carboxylation module to improve natural and synthetic CO2 fixation. Nat. Catal. 4, 105–115 (2021).

Trudeau, D. L. et al. Design and in vitro realization of carbon-conserving photorespiration. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 201812605 (2018).

Zarzycki, J., Sutter, M., Cortina, N. S., Erb, T. J. & Kerfeld, C. A. In vitro characterization and concerted function of three core enzymes of a glycyl radical enzyme—associated bacterial microcompartment. Sci. Rep. 7, 42757 (2017).

Karim, A. S. et al. In vitro prototyping and rapid optimization of biosynthetic enzymes for cell design. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 912–919 (2020).

Hunt, A. C. et al. A rapid cell-free expression and screening platform for antibody discovery. Nat. Commun. 14, 3897 (2023).

Silverman, A. D., Karim, A. S. & Jewett, M. C. Cell-free gene expression: an expanded repertoire of applications. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 151–170 (2020).

Hunt, A. C. et al. Cell-free gene expression: methods and applications. Chem. Rev. 125, 91–149 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Construction of an artificial phosphoketolase pathway that efficiently catabolizes multiple carbon sources to acetyl-CoA. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002285 (2023).

Hopf, T. A. et al. Mutation effects predicted from sequence co-variation. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 128–135 (2017).

Shroff, R. et al. Discovery of novel gain-of-function mutations guided by structure-based deep learning. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 2927–2935 (2020).

Zhang, J. & Liu, Y. Computational studies on the catalytic mechanism of phosphoketolase. Comput. Theor. Chem. 1025, 1–7 (2013).

Landwehr, G. M. et al. Accelerated enzyme engineering by machine-learning guided cell-free expression. Nat. Commun. 16, 865 (2025).

Starai, V. J., Celic, I., Cole, R. N., Boeke, J. D. & Escalante-Semerena, J. C. Sir2-dependent activation of acetyl-CoA synthetase by deacetylation of active lysine. Science 298, 2390–2392 (2002).

Marx, C. J., Laukel, M., Vorholt, J. A. & Lidstrom, M. E. Purification of the formate-tetrahydrofolate ligase from Methylobacterium extorquens AM1 and demonstration of its requirement for methylotrophic growth. J. Bacteriol. 185, 7169–7175 (2003).

Bar-Even, A. et al. The moderately efficient enzyme: evolutionary and physicochemical trends shaping enzyme parameters. Biochemistry 50, 4402–4410 (2011).

Mordhorst, S., Maurer, A., Popadić, D., Brech, J. & Andexer, J. N. A flexible polyphosphate-driven regeneration system for coenzyme A dependent catalysis. ChemCatChem 9, 4164–4168 (2017).

Cai, T. et al. Cell-free chemoenzymatic starch synthesis from carbon dioxide. Science 373, 1523–1527 (2021).

Diehl, C., Gerlinger, P. D., Paczia, N. & Erb, T. J. Synthetic anaplerotic modules for the direct synthesis of complex molecules from CO2. Nat. Chem. Biol. 19, 168–175 (2023).

Meng, X. et al. A synthetic methylotroph achieves accelerated cell growth by alleviating transcription-replication conflicts. Nat. Commun. 16, 31 (2025).

Sherkhanov, S. et al. Isobutanol production freed from biological limits using synthetic biochemistry. Nat. Commun. 11, 4292 (2020).

Black, W. B. et al. Engineering a nicotinamide mononucleotide redox cofactor system for biocatalysis. Nat. Chem. Biol. 16, 87–94 (2020).

Black, W. B. et al. Activation-free upgrading of carboxylic acids to aldehydes and alcohols. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.07.28.667276 (2025).

Liew, F. E. et al. Carbon-negative production of acetone and isopropanol by gas fermentation at industrial pilot scale. Nat. Biotechnol. 40, 335–344 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Efficient multicarbon formation in acidic CO2 reduction via tandem electrocatalysis. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 311–318 (2024).

Kay, J. E. & Jewett, M. C. Lysate of engineered Escherichia coli supports high-level conversion of glucose to 2,3-butanediol. Metab. Eng. 32, 133–142 (2015).

Jiang, Y. et al. Multigene editing in the Escherichia coli genome via the CRISPR–Cas9 system. Appl. Environ. Microb. 81, 2506–2514 (2015).

Bassalo, M. C. et al. Rapid and efficient one-step metabolic pathway integration in E. coli. ACS Synth. Biol. 5, 561–568 (2016).

Kwon, Y.-C. & Jewett, M. C. High-throughput preparation methods of crude extract for robust cell-free protein synthesis. Sci. Rep. 5, 8663 (2015).

Jewett, M. C. & Swartz, J. R. Mimicking the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic environment activates long-lived and efficient cell-free protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 86, 19–26 (2004).

Jewett, M. C. & Swartz, J. R. Substrate replenishment extends protein synthesis with an in vitro translation system designed to mimic the cytoplasm. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 87, 465–471 (2004).

Punjani, A., Rubinstein, J. L., Fleet, D. J. & Brubaker, M. A. cryoSPARC: algorithms for rapid unsupervised cryo-EM structure determination. Nat. Methods 14, 290–296 (2017).

Goddard, T. D. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 27, 14–25 (2018).

Jumper, J. et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 596, 583–589 (2021).

Suzuki, R. et al. Crystal structures of phosphoketolase thiamine diphosphate-dependent dehydration mechanism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 34279–34287 (2010).

Morin, A. et al. Collaboration gets the most out of software. eLife 2, e01456 (2013).

Luc, W., Rosen, J. & Jiao, F. An Ir-based anode for a practical CO2 electrolyzer. Catal. Today 288, 79–84 (2017).

Acknowledgements

Molecular graphics and analyses were performed with UCSF ChimeraX, developed by the Resource for Biocomputing, Visualization, and Informatics at the University of California, San Francisco, with support from National Institutes of Health R01-GM129325 and the Office of Cyber Infrastructure and Computational Biology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. This work made use of the IMSERC MS facility at Northwestern University, which has received support from the Soft and Hybrid Nanotechnology Experimental (SHyNE) Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the State of Illinois and the International Institute for Nanotechnology (IIN). We thank Stanford University Cryo-EM center (cEMc) and particularly B. Singal for providing support for cryo-EM grid preparation, data collection, processing and structure determination pipeline. We thank F. ‘Ralph’ Tobias for his help in developing analytical methods for malate detection and K. Seki for his help in gathering intact protein MS data on the deacetylated acyl-CoA synthetases. We also thank J. W. Bogart for conversations regarding this work. Funding was provided by the Department of Energy (DE-SC0023278) (G.M.L., B.V., K.Z., I.M., A.G., R.L., C.T., E.H.S., A.S.K. and M.C.J.), NSF GRFP (G.M.L.) and Stanford University Cryo-electron Microscopy Center (cEMc) (B.S.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.S.K., B.V., G.M.L. and M.C.J. Methodology: B.V. and G.M.L. Investigation: A.G., C.T., G.M.L., I.M., K.Z. and R.L. Cryo-EM: B.S. Supervision: A.S.K., M.C.J. and E.H.S. Funding acquisition: A.S.K., M.C.J. and E.H.S. Writing: A.S.K., G.M.L. and M.C.J.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

G.M.L., B.V., A.S.K. and M.C.J. have filed an invention disclosure based on the work presented. M.C.J. has a financial interest in National Resilience, Gauntlet Bio, Pearl Bio, Inc., and Stemloop Inc. M.C.J.’s interests are reviewed and managed by Northwestern University and Stanford University in accordance with their competing interest policies. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Chemical Engineering thanks Mattheos Koffas, Zaigao Tan and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Methods, Figs. 1–39 and Tables 1–11.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 2

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 3

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 4

Statistical source data.

Source Data Fig. 5

Statistical source data.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Landwehr, G.M., Vogeli, B., Tian, C. et al. A synthetic cell-free pathway for biocatalytic upgrading of formate from electrochemically reduced CO2. Nat Chem Eng 3, 57–69 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-025-00315-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44286-025-00315-6