Abstract

In this study, we assessed if women with endometriosis have greater odds than matched controls of receiving an autoimmune diagnosis within two-years of their endometriosis diagnosis. We conducted a retrospective cohort study using two large-scale administrative claims databases (2010–2017), identifying 332,409 patients with endometriosis and 1,220,932 matched controls. Compared to matched controls, patients with endometriosis had an increased risk of being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, pernicious anemia, Sjogren’s syndrome or myositis within two-years of their endometriosis diagnosis. The odds of receiving a diagnosis of at least one of the autoimmune conditions among patients with endometriosis were approximately two times greater than matched controls. Our study is the first to show a significant association between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions within a two-year diagnosis window, adding to growing evidence suggesting a potential link between endometriosis and autoimmunity, warranting investigation into shared mechanisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endometriosis is a systemic inflammatory disease characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue beyond the uterine cavity1,2,3,4. The condition is estimated to affect 10% of reproductive age women, with common symptoms including chronic pain and infertility5,6,7,8. Autoimmune diseases are conditions that occur when the body’s immune system attacks and damages its own healthy tissue9. Autoimmune conditions affect approximately 8% of people, with women accounting for 80% of these cases10.

Given the overlapping clinical features and impact of both endometriosis and autoimmune conditions on quality of life, several studies have investigated potential links. These studies have shown an association between endometriosis and a range of autoimmune conditions, including lupus erythematosus11,12,13,14,15,16, rheumatoid arthritis11,13,15,17,18,19, Hashimoto’s disease16, inflammatory bowel disease14,20, Grave’s disease21, multiple sclerosis12, Sjögren’s syndrome11,12,14,22, celiac disease16, and ankylosing spondylitis23. The rationale for exploring this co-occurrence are potential shared immunopathogenic mechanisms between autoimmune conditions and endometriosis, such as chronic inflammation and immune cell dysregulation. The presence of ectopic lesions in patients with endometriosis results in a cascade of inflammation that promotes further adhesions and scar formation, along with subsequent increases in the release of prostaglandins, cytokines, and inflammatory products24. This proposed role of immune cells in the development of endometriosis is supported by findings that women with endometriosis have increased levels of peritoneal neutrophils and macrophages, suppressed natural killer cell activity, reduced myeloid dendritic cell density in the endometrium, and abnormal T-cell functioning25,26,27. These patterns of chronic inflammation and immune cell dysregulation also play a role in mediating the pathogenesis in various autoimmune diseases, supporting the plausibility of a link between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions28,29,30.

While past findings suggest a link between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions, the temporal relationship between these diagnoses remains unclear. Determining whether these conditions are diagnosed within a similar timeframe is essential for understanding if immunodeficiencies associated with endometriosis contribute to the development of comorbid autoimmune conditions. To date, however, investigations into the association between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions have only explored the association over patients’ lifetime and have not assessed if the association remains significant within a defined diagnostic time-window. Thus, we conducted a retrospective cohort study to test if women with endometriosis have greater odds than matched control patients of receiving an autoimmune diagnosis within two-years of their initial endometriosis diagnosis. Additionally, most past studies were limited to specific research cohorts and moderate sample sizes; in contrast, we explore the association between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions within large observational cohorts, reflective of routine care patterns in the United States.

Results

Study population

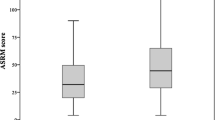

A total of 332,409 women with endometriosis were identified: 278,757 from CCAE and 53,652 from MDCD. Our comparison cohort included 1,220,932 women without endometriosis: 1,017,539 from CCAE and 203,393 from MDCD. A demographic breakdown of patients is provided in Table 1. and a breakdown of patients with a diagnosis of each autoimmune condition analyzed is provided in Table 2. Among patients with endometriosis, 4.93% (n = 11,520) received a diagnosis of at least one autoimmune condition within two-years of their endometriosis diagnosis. The prevalence of autoimmune conditions among the comparison cohort was lower with only 1.42% (n = 17,380) receiving an autoimmune diagnosis within two-years of entering the cohort.

Autoimmune comorbidities

All reported odds ratios (ORs) in this analysis were Bonferroni corrected to account for multiple comparisons. Analysis using a 1-year observation period on the CCAE database (Table 3) showed patients in the endometriosis cohort (n = 196,009) had significantly higher odds than comparison patients (n = 705,781) of receiving a diagnosis of Rheumatoid arthritis (OR = 2.32–2.82), type 1 diabetes mellitus (OR = 1.27–1.60), Hashimoto’s disease (OR = 2.25–2.77), systemic lupus erythematosus (OR = 2.55–3.27), multiple sclerosis (OR = 2.55–3.27), pernicious anemia (OR = 2.44–3.55), Sjögren’s syndrome (OR = 3.43–5.03), Myositis (OR = 3.79–5.92), and Graves’ disease (OR = 1.46–4.55) within the 2-year diagnosis window. When the observation period was expanded to 3-years (Table 3), the association between endometriosis and type I diabetes mellitus (OR = 0.84–1.26) was no longer significant (n = 82,748 endometriosis cohort; n = 311,758 control cohort).

Similarly, when a 1-year observation period was applied to patients in the MDCD database (Table 4), patients in the endometriosis cohort (n = 35,547) had significantly higher odds than comparison patients (n = 141,130) of being diagnosed with each of the 10 autoimmune conditions analyzed. When the Bonferroni correction was applied, the association between endometriosis and Grave’s disease (OR = 0.75–7.37) was no longer significant. Analysis using a 3-year observation period with the MDCD database (Table 4) also showed patients in the endometriosis cohort (n = 16,105) had significantly higher odds than comparison patients (n = 62,263) of being diagnosed with all 10 of the autoimmune conditions analyzed. When the Bonferroni correction was applied, the association between endometriosis and vitiligo (OR = 0.97–5.87) was no longer significant.

When considering all autoimmune conditions combined (Table 5), women with endometriosis in both CCAE and MDCD databases had significantly greater odds (p < 0.01) of receiving an autoimmune diagnosis within the 2-year diagnosis window relative to women without endometriosis. Results were significant for both observation periods. These results remained significant after applying the Bonferroni correction.

Discussion

The present study is the first large-scale investigation to explore the association between endometriosis and 10 distinct autoimmune conditions on real world observational health data using a two-year diagnosis window. Compared to matched controls, patients with endometriosis had a modestly increased risk of being diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, or pernicious anemia, and a large increase in risk of being diagnosed with Sjögren’s syndrome or myositis within two-years of receiving their endometriosis diagnosis. We also found that the odds of receiving a diagnosis of at least one of the autoimmune conditions analyzed was roughly two times greater among patients with endometriosis compared to matched controls.

Our results are consistent with findings from other large-scale studies showing an association between endometriosis and a range of autoimmune conditions. These include Rheumatoid arthritis11,13,17,18,19, systemic lupus erythematosus11,12,13,14,15, multiple sclerosis12, Sjögren’s syndrome11,12,14,22, and Grave’s disease21. Of note, however, smaller scale studies exploring the association between endometriosis and Hashimoto’s disease have found conflicting results16,31.

These past findings, coupled with our results suggest endometriosis and autoimmune conditions may share biological pathways. However, further investigation is needed, with adjustments for potential confounding factors. Defects in T cell and regulatory cell functioning, as well as abnormal levels of prostaglandins, cytokines, and inflammatory products have all been observed among patients with endometriosis24,25,27 as well as patients with several autoimmune conditions32,33. To date, however, explorations into shared genetic variants between endometriosis and autoimmunity have shown mixed results34. For instance, a large genome-wide analysis showed genetic correlations between endometriosis and inflammatory conditions such as asthma and osteoarthrosis, but no genetic correlation between endometriosis and any of the autoimmune conditions analyzed, including inflammatory bowel disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis35. However, a more recent study examining phenotypic and genetic associations between endometriosis and 31 autoimmune conditions found significant positive genetic associations between endometriosis and rheumatoid arthritis and multiple sclerosis36.

While the evidence of a genetic correlation shows mixed results, a potential alternative explanation is that the systemic chronic inflammation experienced by patients with endometriosis1, increases risk for developing a comorbid autoimmune condition37. Both endometriosis and autoimmune conditions are systemic inflammatory diseases, impacting multiple organ systems throughout the body1,2,3,4. Notably, the presence of systemic chronic inflammation can increase risk for developing numerous chronic conditions, including autoimmune conditions17,38,39,40. Therefore, it is possible that the genetic correlation between endometriosis and inflammatory conditions, coupled with the systemic and chronic inflammatory nature of endometriosis contribute to the development of co-morbid autoimmune conditions observed among patients with endometriosis. Previous research has shown that patients with endometriosis present with elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including Interleukin-1 (IL-1), Interleukin-6 (IL-6), and Interleukin-8 (IL-8)41. These same pro-inflammatory cytokines are also recognized as playing a role in mediating the pathogenesis in various autoimmune diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus28,29,30. If this is the case, it may also explain why the increased risk of concomitant autoimmunity among patients with endometriosis have ranged from minimal to large within our findings and in past research. Since systemic chronic inflammation can be influenced by age, as well as social, environmental, and lifestyle factors, it is possible that exposure to these factors, and their contribution to systemic chronic inflammation varied across the populations studied. Additionally, while pre-existing systemic chronic inflammation has yet to be investigated as a contributing factor to the development of endometriosis, it may also be possible that the inflammatory nature of autoimmune conditions similarly increases risk for developing endometriosis.

Our study is the first to show a significant association between endometriosis and autoimmune conditions within a two-year diagnosis window. Our results do suggest that prior to giving an endometriosis diagnosis, clinicians likely consider and test patients for a range of other conditions which likely results in many patients with endometriosis receiving multiple diagnoses, including autoimmune diagnoses, within a condensed timeframe. Additionally, preliminary findings also suggest that concomitant autoimmunity is a predictor of later stage endometriosis42, suggesting that by the time an undiagnosed endometriosis patient has developed and been diagnosed with a comorbid autoimmune condition, their endometriosis has likely progressed to a more severe stage, which in turn may increase the likelihood their endometriosis will finally be diagnosed.

A significant strength of the study is the use of two comprehensive databases. CCAE provides healthcare claims from over 30 million individuals annually, all beneficiaries of private insurance plans. Additionally, this study utilizes MDCD, which provides data from individuals enrolled in Medicaid. This combination of databases allows for a thorough investigation of healthcare patterns and outcomes across diverse insurance frameworks, thereby enhancing the generalizability of the research findings. Another key strength is the consistency of results observed across different databases and observation periods, indicating the reliability of our findings. Furthermore, the use of a validated phenotype for endometriosis ensures methodological rigor, enhancing the accuracy of our study’s conclusions.

Our findings should be considered in light of the study’s limitations. First, the study’s retrospective cohort design precludes the establishment of causality or directionality. Therefore, while our findings indicate an association, they do not confirm a causal relationship.

Second, our analysis relies on administrative health claims data which might introduce selection bias, as this type of data can be incomplete. Specifically, the data only identifies patients who have received a diagnosis, potentially capturing more symptomatic cases and missing milder cases. This raises the possibility that the observed association could partially reflect that women with both an autoimmune disease and endometriosis present with more severe symptoms, leading to a higher likelihood of both conditions being diagnosed, rather than reflecting shared underlying biological pathways. Additionally, identifying both autoimmune conditions and endometriosis relies on diagnosis codes within the claims data. While we used validated phenotypes when available, relying on diagnosis codes may result in misclassification due to coding errors. The use of claims data also reduces our ability to comprehensively control for confounders. While administrative claims data allows for a large sample size, it lacks the granularity of prospective, curated data sources. Specifically, important covariates such as Body Mass Index (BMI), inflammation, socioeconomic status, detailed pregnancy/family history, lifestyle factors, and clinical characteristics of endometriosis (e.g., stage, primary symptoms), are not reliably captured. Therefore, we conducted a bivariate analysis by matching on age and visit date, making our results subject to residual confounding.

Another limitation of our data source is the lack of race and ethnicity data in the CCAE database, which limits our ability to assess potential racial or ethnic differences in the observed associations. Given these limitations of claims data and retrospective studies, we acknowledge that these findings require confirmation through studies designed to minimize such biases. Future research could use prospective cohorts or data sources such as Electronic Health Records (EHRs) that allow for more detailed clinical and demographic assessment and comprehensive multivariable analysis.

The study faces challenges due to the known delays in diagnosing endometriosis43,44 and several autoimmune conditions45,46, which might cause discrepancies between the actual onset of diseases and their documentation in the databases. As a result, we are unable to ascertain if the onset of comorbid autoimmune conditions reported by patients with endometriosis in this study occurred before, after or in tandem with the onset of their endometriosis. Thus, further investigation is needed to determine if the onset of endometriosis coincides with the onset of the autoimmune conditions analyzed. Before such an investigation can be conducted, however, diagnostic lags must be shortened, which will require further research to improve our understanding of these conditions and ability to identify them.

In conclusion, the present study is the first to show a significant association between endometriosis and several autoimmune conditions within a two-year diagnosis window. While our results show an association between the diagnosis of endometriosis and autoimmune conditions, it is important to note that we are unable to draw conclusions about disease onset due to known diagnostic lags. Future work is therefore needed to shorten time to diagnosis, which will enable further research to assess if the onset of endometriosis and autoimmune conditions coincide. Additionally, investigations into the underlying mechanisms driving the observed associations are crucial to better understand the potential shared biological pathways.

Methods

The analysis and the use of the de-identified dataset presented in this work were carried out under Research Protocol AAAR6505 approved by the Columbia University IRB. All research activities were conducted in accordance with ethical regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki.

This study leverages the Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) framework47 to conduct a retrospective cohort study at scale. OHDSI is an international research network working to support reliable medical evidence generation by developing open-source standards for the structure and content of observational health data48,49. In following OHDSI’s approach, surgically confirmed endometriosis cohorts and comparison cohorts were generated from two administrative claims databases formatted to the OHDSI standard.

Data source

This study utilized two comprehensive deidentified administrative claims databases: the Merative MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters (CCAE) database and the Merative Multi-State Medicaid (MDCD) database. CCAE is comprised of data from patients with US employer-based health insurance and contains detailed records of healthcare coverage and service utilization for active employees, early retirees, COBRA participants, and any dependents also insured under employer-sponsored plans. MDCD includes data on the healthcare coverage and service usage for individuals enrolled in Medicaid programs across multiple states, including those in Medicaid-managed care programs.

Both CCAE and MDCD are populated with patient demographics, healthcare visits, disease diagnoses, medications, procedures, and other data types such as laboratory tests. In OHDSI standardized databases, patient data pertaining to diagnoses and procedures can be identified and extracted using Systematized Nomenclature of Medicines50. Similarly, medications can be identified using RxNorm codes51, and Logical Observation Identifiers52 can be used to identify laboratory test data.

Cohort identification

We identified patients with endometriosis using a validated endometriosis cohort definition53,54. The cohort included women ages 15–49 who underwent an endometriosis-related surgical or prevalent procedure and had an endometriosis concept code documented 30 days before or after the procedure, along with an additional endometriosis concept code in their record at any time following the procedure. The phenotype has been validated with a manual chart review of 430 patients from claims and EHR data with a sensitivity of 70%, specificity of 93%, and positive predictive value of 85%. Additional information about our endometriosis cohort is available in the supplemental materials.

The control group included females aged 15–49 who had no previous diagnosis of endometriosis. These individuals were matched to the endometriosis cohort at a ratio of 4:1. Matching criteria were age ( ± 1 year), and the occurrence of an outpatient visit on the exact day the endometriosis patient entered the cohort.

Both cohorts required a minimum of one year of medical observation to ensure adequate time for outcome assessment. Additional analyses were also conducted for those with observations spanning at least three years. Patients with a prior autoimmune diagnosis were not excluded from the cohort. This decision was made considering that patients with one autoimmune condition are at a significantly increased risk of developing additional autoimmune conditions55,56. Therefore, excluding patients with a prior autoimmune diagnosis would not accurately represent the actual population and may underestimate the true association observed in our dataset, limiting generalizability.

Utilizing validated phenotype definitions57,58 that have been made publicly available by the OHDSI research network (https://ohdsi.github.io/PhenotypeLibrary/), we established 10 distinct cohorts corresponding to common and representative autoimmune diseases in the United States: Rheumatoid arthritis, type 1 diabetes mellitus, Hashimoto’s disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, multiple sclerosis, pernicious anemia, Sjögren’s syndrome, myositis, vitiligo, and Graves’ disease55. Only patients who received an autoimmune diagnosis two-years before or after their index endometriosis diagnosis date or the corresponding index date for matched controls were included in these cohorts. The selection of the two-year window was informed by examining the distribution of time differences between patients’ autoimmune diagnosis and endometriosis diagnosis in our data. This analysis revealed mean time differences of 677 days in the CCAE cohort and 669 days in the MDCD cohort. Therefore, a two-year window (representing a total of four years, −730 days to +730 days) captured a substantial portion of the observed autoimmune diagnoses. Additional details about these cohorts can be found in the supplemental materials.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed to summarize demographic characteristics. We also tabulated a breakdown of endometriosis and comparison patients who received a diagnosis of each autoimmune disease analyzed. To achieve our study aim, we employed the Fisher’s exact test to calculate odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each autoimmune disease in relation to endometriosis. This approach allowed us to obtain precise measurements of the odds ratios, ensuring exactness in our calculations59. Due to the limited covariates available in administrative claims data (detailed in Discussion), we did not perform a multivariable analysis. Separate analyses were run for one-year and three-year observation periods on each database. For each observation period and database, 11 separate tests were run; one for each distinct autoimmune disease and an additional test of the aggregate of all autoimmune diseases combined. To account for potential Type I error due to multiple comparisons, we applied the Bonferroni correction. This approach adjusts the significance threshold downward, based on the number of tests performed, ensuring that the results remained robust against potential false positives. We consider the association significant if p < 0.0045. All analyses were carried out using Python.

Data availability

The Merative Marketscan CCAE and MDCD databases used in this study are available to license through Merative at https://www.merative.com/documents/brief/marketscan-explainer-general.

Code availability

Code for cohort definitions is available through the OHDSI Phenotype Library and at https://github.com/elhadadlab/endochar. Analysis code is publicly available via GitHub at: https://github.com/maryam-aziz1/endo_autoimmune_analysis.

References

Zondervan, K. T., Becker, C. M. & Missmer, S. A. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med 382, 1244–1256 (2020).

Taylor, H. S., Kotlyar, A. M. & Flores, V. A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 397, 839–852 (2021).

Tulandi, T. & Vercellini, P. Growing evidence that endometriosis is a systemic disease. Reprod. Biomed. Online 49, 104292 (2024).

Bao, C., Wang, H. & Fang, H. Genomic Evidence Supports the Recognition of Endometriosis as an Inflammatory Systemic Disease and Reveals Disease-Specific Therapeutic Potentials of Targeting Neutrophil Degranulation. Front Immunol. 13, 758440 (2022).

Meuleman, C. et al. High prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women with normal ovulation and normospermic partners. Fertil. Steril. 92, 68–74 (2009).

Ashrafi, M., Sadatmahalleh, S. J., Akhoond, M. R. & Talebi, M. Evaluation of Risk Factors Associated with Endometriosis in Infertile Women. Int J. Fertil. Steril. 10, 11–21 (2016).

Maddern, J., Grundy, L., Castro, J. & Brierley, S. M. Pain in Endometriosis. Front Cell Neurosci. 14, 590823 (2020).

Agarwal, S. K. et al. Clinical diagnosis of endometriosis: a call to action. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 220, 354 e351–354.e312 (2019).

Institute, N. C. Autoimmune disease, https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/autoimmune-disease.

National Institutes of Health, O. o. R. o. W. s. H. Office of Autoimmune Disease Research, https://orwh.od.nih.gov/OADR-ORWH (2025).

Sinaii, N., Cleary, S. D., Ballweg, M. L., Nieman, L. K. & Stratton, P. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum. Reprod. 17, 2715–2724 (2002).

Nielsen, N. M., Jorgensen, K. T., Pedersen, B. V., Rostgaard, K. & Frisch, M. The co-occurrence of endometriosis with multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 26, 1555–1559 (2011).

Harris, H. R. et al. Endometriosis and the risks of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75, 1279–1284 (2016).

Greenbaum, H., Weil, C., Chodick, G., Shalev, V. & Eisenberg, V. H. Evidence for an association between endometriosis, fibromyalgia, and autoimmune diseases. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 81, e13095 (2019).

Lin, Y. H., Yang, Y. C., Chen, S. F., Hsu, C. Y. & Shen, Y. C. Risk of systemic lupus erythematosus in patients with endometriosis: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 302, 1197–1203 (2020).

Porpora, M. G. et al. High prevalence of autoimmune diseases in women with endometriosis: a case-control study. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 36, 356–359 (2020).

Chen, Z., Bozec, A., Ramming, A. & Schett, G. Anti-inflammatory and immune-regulatory cytokines in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 15, 9–17 (2019).

Xue, Y. H. et al. Increased risk of rheumatoid arthritis among patients with endometriosis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Rheumatol. ((Oxf.)) 60, 3326–3333 (2021).

Yoshii, E., Yamana, H., Ono, S., Matsui, H. & Yasunaga, H. Association between allergic or autoimmune diseases and incidence of endometriosis: A nested case-control study using a health insurance claims database. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 86, e13486 (2021).

Jess, T., Frisch, M., Jorgensen, K. T., Pedersen, B. V. & Nielsen, N. M. Increased risk of inflammatory bowel disease in women with endometriosis: a nationwide Danish cohort study. Gut 61, 1279–1283 (2012).

Yuk, J. S. et al. Graves Disease Is Associated With Endometriosis: A 3-Year Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Med. ((Baltim.)) 95, e2975 (2016).

Chao, Y. H. et al. Association Between Endometriosis and Subsequent Risk of Sjogren’s Syndrome: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Front Immunol. 13, 845944 (2022).

Yin, Z. et al. Risk of Ankylosing Spondylitis in Patients With Endometriosis: A Population-Based Retrospective Cohort Study. Front Immunol. 13, 877942 (2022).

Hamouda, R. K. et al. The Comorbidity of Endometriosis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A Systematic Review. Cureus 15, e42362 (2023).

Izumi, G. et al. Involvement of immune cells in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res 44, 191–198 (2018).

Maridas, D. E. et al. Peripheral and endometrial dendritic cell populations during the normal cycle and in the presence of endometriosis. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain. Disord. 6, 67–119 (2014).

Rizner, T. L. Estrogen metabolism and action in endometriosis. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 307, 8–18 (2009).

Schett, G., Dayer, J. M. & Manger, B. Interleukin-1 function and role in rheumatic disease. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 12, 14–24 (2016).

Ohl, K. & Tenbrock, K. Inflammatory cytokines in systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011, 432595 (2011).

Magyari, L. et al. Interleukins and interleukin receptors in rheumatoid arthritis: Research, diagnostics and clinical implications. World J. Orthop. 5, 516–536 (2014).

Petta, C. A., Arruda, M. S., Zantut-Wittmann, D. E. & Benetti-Pinto, C. L. Thyroid autoimmunity and thyroid dysfunction in women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 22, 2693–2697 (2007).

Jonuleit, H. & Schmitt, E. The regulatory T cell family: distinct subsets and their interrelations. J. Immunol. 171, 6323–6327 (2003).

Takaba, H. & Takayanagi, H. The Mechanisms of T Cell Selection in the Thymus. Trends Immunol. 38, 805–816 (2017).

Bianco, B. et al. The possible role of genetic variants in autoimmune-related genes in the development of endometriosis. Hum. Immunol. 73, 306–315 (2012).

Rahmioglu, N. et al. The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Genet 55, 423–436 (2023).

Shigesi, N. et al. The phenotypic and genetic association between endometriosis and immunological diseases. Hum Reprod. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaf062. (2025).

Furman, D. et al. Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nat. Med 25, 1822–1832 (2019).

Straub, R. H., Cutolo, M., Buttgereit, F. & Pongratz, G. Energy regulation and neuroendocrine-immune control in chronic inflammatory diseases. J. Intern Med 267, 543–560 (2010).

Straub, R. H. & Schradin, C. Chronic inflammatory systemic diseases: An evolutionary trade-off between acutely beneficial but chronically harmful programs. Evol. Med Public Health 2016, 37–51 (2016).

Duan, L., Rao, X. & Sigdel, K. R. Regulation of Inflammation in Autoimmune Disease. J. Immunol. Res 2019, 7403796 (2019).

Mahdy, E. S. T. H. Endometriosis. (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Vanni, V. S. et al. Concomitant autoimmunity may be a predictor of more severe stages of endometriosis. Sci. Rep. 11, 15372 (2021).

Nnoaham, K. E. et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 96, 366–373.e368 (2011).

Hudelist, G. et al. Diagnostic delay for endometriosis in Austria and Germany: causes and possible consequences. Hum. Reprod. 27, 3412–3416 (2012).

Petruzzi, M. et al. Diagnostic delay in autoimmune oral diseases. Oral. Dis. 29, 2614–2623 (2023).

Quintana, R., Ramirez-Flores, M. F., Fuentes-Silva, Y. & Pelaez-Ballestas, I. Diagnostic Delay in Autoimmune Rheumatic Diseases: A Global Health Problem. J Rheumatol. https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.2023-0847 (2023).

Hripcsak, G. et al. Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI): Opportunities for Observational Researchers. Stud. Health Technol. Inf. 216, 574–578 (2015).

Overhage, J. M., Ryan, P. B., Reich, C. G., Hartzema, A. G. & Stang, P. E. Validation of a common data model for active safety surveillance research. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 19, 54–60 (2012).

Hripcsak, G., Schuemie, M. J., Madigan, D., Ryan, P. B. & Suchard, M. A. Drawing Reproducible Conclusions from Observational Clinical Data with OHDSI. Yearb. Med Inf. 30, 283–289 (2021).

Cornet, R. & de Keizer, N. Forty years of SNOMED: a literature review. BMC Med Inf. Decis. Mak. 8, S2 (2008).

Nelson, S. J., Zeng, K., Kilbourne, J., Powell, T. & Moore, R. Normalized names for clinical drugs: RxNorm at 6 years. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 18, 441–448 (2011).

McDonald, C. J. et al. LOINC, a universal standard for identifying laboratory observations: a 5-year update. Clin. Chem. 49, 624–633 (2003).

Kashyap, A. et al. Investigating Racial Disparities in Drug Prescriptions for Patients with Endometriosis. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.10.02.23296435 (2023).

Nieva, H. R. et al. The Impact of Evolving Endometriosis Guidelines on Diagnosis and Observational Health Studies. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.12.13.24319010 (2024).

Jacobson, D. L., Gange, S. J., Rose, N. R. & Graham, N. M. Epidemiology and estimated population burden of selected autoimmune diseases in the United States. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 84, 223–243 (1997).

Pathology, J. H. Prevalence of Autoimmune Disease, https://pathology.jhu.edu/autoimmune/prevalence.

Banda, J. M., Halpern, Y., Sontag, D. & Shah, N. H. Electronic phenotyping with APHRODITE and the Observational Health Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI) data network. AMIA Jt Summits Transl. Sci. Proc. 2017, 48–57 (2017).

Kashyap, M. et al. Development and validation of phenotype classifiers across multiple sites in the observational health data sciences and informatics network. J. Am. Med Inf. Assoc. 27, 877–883 (2020).

Kim, H. Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Chi-squared test and Fisher’s exact test. Restor. Dent. Endod. 42, 152–155 (2017).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Library of Medicine under Grant R01LM013043. Additional support was provided by and the Amazon MS Fellowship at Columbia Engineering. The funder played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, the writing of this manuscript, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors' contributions to the manuscript are as follows: M.A. was responsible for conceptualization, methodology, analysis, validation, and manuscript preparation. M.B. and M.A.A. contributed to the analysis and manuscript preparation. J.O.A. provided clinical validation for the study. N.E. contributed to the methodology, review and editing of the manuscript, and provided supervision throughout the project. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Aziz, M., Beaton, M.A., Aziz, M.A. et al. Endometriosis and autoimmunity: a large-scale case-control study of endometriosis and 10 distinct autoimmune diseases. npj Womens Health 3, 36 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00086-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44294-025-00086-8