Abstract

Viruses in the phylum Nucleocytoviricota are large, complex and have an exceptionally diverse metabolic repertoire. Some encode hundreds of products involved in the translation of mRNA into protein, but none was known to encode any of the proteins in ribosomes, the central engines of translation. With the discovery of the eL40 gene in FloV-SA2, we report the first example of a eukaryotic virus encoding a ribosomal protein and show that this gene is also present and expressed in other uncultivated marine giant viruses. FloV-SA2 also encodes a “group II” viral rhodopsin, a viral light-activated protein of unknown function previously only reported in metagenomes. FloV-SA2 is thus a valuable model system for investigating new mechanisms by which viruses manipulate eukaryotic cell metabolism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many recent discoveries have expanded our knowledge of the viral phylum Nucleocytoviricota1. These viruses possess double-stranded DNA genomes and infect a wide range of eukaryotic organisms, including animals, plants, and protists. This phylum is of particular interest because of their large genome sizes (up to 2.7 Mbp)2,3, leading to the colloquial term ‘giant viruses’ for the largest among them, and the broad spectrum of functional genes they encode, including many involved in processes that had previously been seen only in cellular genomes. This includes gene products that play a central role in diverse metabolic processes such as central carbon metabolism (i.e. TCA cycle, glycolysis)4,5, sugar and amino-acid metabolism6,7,8, light sensing9,10,11,12,13,14, sphingolipid biosynthesis15,16, cytoskeletal structure17,18, and fermentation19. Large viral genome size is also associated with the presence of many genes related to genome replication, making them “quasi-autonomous” from the host replication machinery20. Various genes related to protein translation have also been reported in these large viral genomes. For example, the Acanthamoeba polyphaga mimivirus, recently classified as the species Mimivirus bradfordmassiliense21, harbors tRNAs, translation factors, and four aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases that had only been previously found in the genomes of cellular organisms22. Other notable examples are members of the Klosneuvirinae group and Tupanvirus, which encode the most complete translational apparatuses in the known virosphere23,24,25.

Despite this documented abundance of translation-related genes, proteins encoding the ribosome itself have never been reported in any member of the phylum Nucleocytoviricota. A recent search of viral genomes uncovered numerous examples of ribosomal protein genes in the genomes of bacterial viruses, and evidence that these are widespread in the environment, but only one example in the genome of a eukaryote-infecting virus (eukaryovirus) of any sort (a murine retrovirus)26. In the latter case, the viral gene does not produce a protein, but is transcribed as an antisense RNA that suppresses expression of the host gene27. Thus, there is scant evidence to date that ribosomal proteins are part of the diverse repertoire of metabolic genes found in any eukaryovirus.

Here, we present an analysis of the genome of FloV-SA2, a cultivated marine virus in the family Mesomimiviridae (phylum Nucleocytoviricota), with particular emphasis on the notable features of this genome. Specifically, we report that FloV-SA2 encodes both a ribosomal protein (eL40) and a Group II viral rhodopsin, and we discuss the affiliations and possible origins of these genes. We also present evidence from analysis of existing metagenomic and metatranscriptomic data that the gene eL40 is present and expressed in other giant viruses. These data expand our understanding of the metabolic versatility of eukaryoviruses and suggest additional mechanisms by which viruses redirect host resources and energy.

Results

Traits and genetic features of the FloV-SA2 virus

FloV-SA2 was isolated from open ocean seawater using a marine microalga strain (UHM3020) in the genus Florenciella (class Dictyochophyceae) as a host. Two other closely related Florenciella strains (UHM3011 and UHM3029, with >95% nucleotide identity to each other for the 18S rRNA gene) were also susceptible to FloV-SA2. However, cell lysis was not observed for another two very closely related strains within the genus (Florenciella sp. UHM3000 and UHM3005, with >99% nucleotide identity to each other for the 18S rRNA gene), nor for two strains belonging to other dictyochophyte genera, Clade X (DictyX; UHM3054) and Rhizochromulina sp. (UHM3072), suggesting a narrow (species- to strain-level) host range (Supplementary Fig. 1a). FloV-SA2 produces non-enveloped virions with an icosahedral capsid having a diameter of approximately 205 ± 7 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1b) and a buoyant density in CsCl of 1.395 ± 0.005 (mean ± s.d.).

The FloV-SA2 genome was fully assembled as a linear DNA sequence of 487,887 base pairs (bp) with a G + C nucleotide content of 26.7% (Fig. 1a). The genome is compact, with 1.14 genes/kb and a total of 575 genes predicted, including 559 coding sequences (CDSs) and 16 tRNAs. The average CDS length is 781.9 bp and the gene-coding density is 92.15%. Of the 575 proteins predicted in FloV-SA2, 287 (~50%) have homology to known protein families in the nr NCBI and EggNOG databases (Supplementary Table 1). The majority of these orthologs have top BLASTp hits in NCBI RefSeq to bacteria (80) and eukaryotes (79), followed by viruses (44) and archaea (5). The most common COG categories of genes with putative functions are post-translational modification, protein turnover and chaperones; replication, recombination and repair; and transcription; followed by diverse other categories typical of giant viruses (Supplementary Fig. 2)28.

a Circular map of the full linear genome of FloV-SA2. ORFs are indicated with gray boxes and the eL40 and ubiquitin (UB) proteins in purple. The outermost and second outermost rings are the forward and reverse strands, respectively. The green and red ring represents the GC content (%) per sliding window with GC above and below average in green and red, respectively. The blue and orange ring shows the GC skew. Numbers on the ring exterior indicate position in the genome (kbp). b Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic reconstruction of the newly isolated virus, FloV-SA2 (bolded and indicated with the red star), and other Nucleocytoviricota isolates, based on a concatenated alignment of seven marker proteins (5,065 aa sites). The LG + F + R6 best-fit model was chosen according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Nodes with bootstrap support over 70% are shown as filled circles in the tree. The scale bar represents the average number of substitutions per site.

A phylogenetic tree constructed using seven concatenated marker genes (SFII, RNAPL, PolB, TFIIB, TopoII, A32, and VLTF3)1 places FloV-SA2 adjacent to two uncultivated viruses assembled from metagenomes (Organic lake phycodnavirus 1 and 2)29, as a novel member of the family Mesomimiviridae within the order Imitervirales (Fig. 1b).

The first ribosomal protein eL40 encoded in a cultivated viral genome

A gene encoding ribosomal protein eL40, a component of the large 60S ribosomal subunit in eukaryotes and archaea30, was identified in the FloV-SA2 genome (Fig. 1a). The predicted FloV-SA2 eL40 protein (Genbank Acc. XDO01897.1) has 53 amino acids (aa) and exhibits highest similarity (84.6% aa identity) to a sequence in the genome of the Florenciella host strain (GenBank Acc. XDO02386.1) (Supplementary Fig. 3). A high identity with homologs was also identified in other classes of stramenopiles such as a pelagophyte strain (class Pelagophyceae; GenBank Acc. KAJ1456274.1; 81.13% aa identity) and a Nannochloropsis salina strain (class Eustigmatophyceae; GenBank Acc. TFJ84430.1; 80.77% aa identity). The predicted structures of the FloV-SA2 eL40 and these cellular homologs also exhibit strong conservation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3). In most eukaryotes eL40 is the C-terminal domain of a ubiquitin-eL40 fusion protein (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3). Although FloV-SA2 does not appear to code for the typical fusion protein, a ubiquitin gene with very high sequence identity and tertiary structure to host cellular homologs (Fig. 2a, b) was found elsewhere in the FloV-SA2 genome (Fig. 1a) (Genbank Acc. XDO02293.1). The three top BLAST hits to the FloV-SA2 ubiquitin were from members of the eukaryotic “SAR” clades (Stramenopiles, Alveolates and Rhizaria): Tetrahymena thermophila (GenBank Acc. P0DJ25.1), Nannochloropsis salina strain (GenBank Acc. TFJ84430.1) and Hepatocystis (GenBank Acc. VWU51464.1), all with 97.3% aa identity and high predicted structural conservation (Supplementary Fig. 3). In addition, a homologous ubiquitin (97.3% aa identity) was identified in the Florenciella host, as the N-terminal domain of a fusion protein with eL40 (Fig. 2b).

a 3D structure of the eL40 protein (FloV-SA2_00074) and ubiquitin protein (FloV-SA2_00475) detected in the FloV-SA2 genome (yellow), compared to (b) the fused ubiquitin-60S ribosomal protein eL40 in the Florenciella sp. host genome (gold), as predicted by ColabFold. c The number of eL40 and ubiquitin gene copies detected in different Nucleocytoviricota orders or superclades (SCx). The pie chart shows the number of Nucleocytoviricota MAGs encoding a ribosomal protein eL40 (either fused to ubiquitin or unfused). The table and barcharts compare frequencies of different forms of ubiquitin and eL40 detected in the viral metagenomes. UB genomes contain only the ubiquitin protein, UB/eL40 genomes contain both ubiquitin and eL40, but not fused, eL40 genomes contain only an eL40 protein, and UB-eL40 genomes contain ubiquitin N-terminally fused to eL40).

Giant-virus-associated eL40 genes are present and expressed in the ocean

A search of 3272 Giant Virus Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (GVMAGs) identified 64 eL40 proteins in 61 (1.9%) of the GVMAGs, with three of the GVMAGs each containing two copies. Investigation into the distribution of ubiquitin and eL40 revealed that 1,207 GVMAGs encode either ubiquitin and/or eL40 (Supplementary Table 2). A substantial fraction of GVMAGs (1156 out of 3,272, or 35%) coded for one or multiple ubiquitin copies (a total of 1,311 instances), and no ribosomal protein (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 2). Among those that had the eL40 gene (n = 61), 30 (49%) had no ubiquitin and 23 (37%) had ubiquitin elsewhere in the genome. Finally, only 18% (11 out of 61 GVMAGs) possessed the ubiquitin-eL40 fusion protein common in eukaryotes. Among the GVMAGs is the uncultivated ChoanoV1 virus, for which two ubiquitins and one eL40 (Genbank Acc. QDY52378.1) were found decoupled in the genome. In the three GVMAGs that each contained two copies of eL40 (ERX555957.21, GVMAG-M-3300001589-11, GVMAG-S-ERX555957-35) the aa identity between the two paralogs varied from 78%–92%. The Imitervirales order contained the most instances of viral ubiquitin and/or eL40 sequences (n = 863), followed by Pimascovirales (n = 133) and Algavirales (n = 100) (Fig. 2c). The eL40 protein was also found in superclades SC10, SC6 and SC5, which have not been taxonomically assigned to an order at this point. The low ratios of non-synonymous (dN) to synonymous substitution (dS) rates across virus-encoded eL40 genes (average dN/dS = 0.20 and an average p-value < 0.001 across all alignments; Supplementary Table 3) implies that these proteins are under strong purifying selection.

Of the 64 eL40 and 1334 ubiquitin identified in the GVMAG dataset, one eL40 protein and 35 ubiquitin genes were detected as transcripts in metatranscriptomic dataset from California coastal waters reported by Ha et al.31. Relative expression of ubiquitin genes from various GVMAGs ranged from 0.19 to 13 transcripts per million (TPM) with an average of 1.98 ± 1.29. An eL40 gene was detected at ten different time points at an average of 50 TPM, which was higher than all but one of the ubiquitin genes (Supplementary Table 2). The ribosomal protein gene detected derives from the uncultivated GVMAG ERX552270.56, affiliated with the Schizomimiviridae family within the order Imitervirales21. Including the eL40 gene, a total of 131 out of the 559 GVMAG ERX552270.56 genes (23%) were found in this dataset (Supplementary Table 4). Most of these genes encode proteins associated with COG categories for nucleotide transport and metabolism; post-translational modification; protein turnover, chaperones; replication; and recombination and repair (Supplementary Fig. 4). The eL40 ribosomal protein was the most highly expressed gene from this GVMAG over the sampling period, accounting for about 26% of total ERX552270.56 transcripts in the dataset (Supplementary Fig. 4). The second most highly expressed gene was an isocitrate lyase protein (9%), a key enzyme used in the glyoxylate cycle, playing a role in lipid metabolism and carbon assimilation in algae32,33.

Phylogenetic reconstruction reveals a complex evolutionary history of the eL40 protein

Phylogenetic analysis of eL40 amino acid sequences from protists and viruses (isolates and MAGs) suggests a complex evolutionary history in which viruses appear to have acquired eL40 genes mainly from two different lineages, i.e. the SAR and Obazoa clades, independently through multiple acquisition events (Fig. 3). The sequences from FloV-SA2 and its host (Florenciella sp.) have relatively high similarity (84.6%), but neither was the nearest virus-cell pairing for the other. Specifically, the closest viral eL40 sequence to that of the Florenciella sp. host is from a homolog in a GVMAG (TARA_PSE_NCLDV_00029) which has been detected in the Southeast Pacific34. Conversely, the cell-derived eL40 sequence most similar to that of FloV-SA2 is an eL40 sequence (GenBank Acc. KAJ1456274.1) from a pelagophyte isolate. The overall most similar eL40 sequence to that of the Florenciella sp. host was a sequence (GenBank Acc. CBN78090.1) from another stramenopile, the brown alga Ectocarpus siliculosus (Class Phaeophyceae). The overall most similar sequence to the eL40 of FloV-SA2 was from a marine GVMAG (ERX552270.65.fa.dc) with which it shared 100% aa identity. The topology of this portion of the tree suggests that diverse viral seL40 genes, including that of FloV-SA2, originated from one or more transfer events from a SAR host (Fig. 3).

Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic reconstruction of ribosomal protein eL40 (53 aa sites) detected in eukaryote and virus genomes. Taxonomic affiliation of eukaryotic lineages is indicated by color in the outer ring. In addition to the genes from FloV-SA2 and its Florenciella host (branches marked with red stars and labels outside the outer ring) the tree includes genes from uncultivated eukaryotes (black branches, no symbol in outer ring), cultivated eukaryotes (magenta branches, black circles in the outer ring), and uncultivated Nucleocytoviricota viruses (black branches highlighted with light gray wedges, white squares outside the ring). Paralogous pairs are indicated with letters. The best-fit amino acid substitution model (Q.insect + I + G4) was chosen according to the Bayesian information criterion (BIC). Nodes with bootstrap support over 80% are marked with filled circles. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae homologous sequence (GenBank Acc. GAX70831.1) was used as an outgroup. The scale bar represents the average number of substitutions per site.

The phylogeny also includes a clade of diverse MAG-derived viral sequences which derives from a putative Obozoa ancestor, and this viral clade includes the putative choanoflagellate virus ChoanoV1, and is sister to two MAG-derived putative choanoflagellate sequences (Fig. 3). The cultivated choanoflagellate Salpingoeca rosetta (GenBank Acc. XP_004998077.1) is the closest cultivated relative of this viral clade, and the S. rosetta sequence shares 70% aa identity with the ChoanoV1 sequence. The inferred ancestry of this viral clade is sensitive to the inclusion of MAG-derived eukaryote sequences; a phylogeny using only cultivated eukaryote sequences finds that the closest relatives of the ChoanoV1 clade were from a variety of eukaryotic groups, mostly excavates, and Entamoeba nuttalli (XP_008859274.1) is the closest Obazoa (59% aa identity) (Supplementary Fig. 5). More thorough sampling of protistan and viral diversity will be needed to draw robust conclusions about the number of HGT events involving eL40 and their directionality. Finally, as previously noted, three GVMAGs encode two distinct copies of eL40 protein in their genomes (Fig. 3). The presence of multiple pairs of paralogs in one of the viral clades suggests one or more duplication events, but the evolutionary history is difficult to assess without complete virus and host genomes.

The FloV-SA2 genome encodes a viral rhodopsin

Another notable finding is the presence of a putative rhodopsin in the FloV-SA2 genome, which we will refer to as FloVR, consisting of 233 aa. Secondary structure and alphaFold2-based three-dimensional (3D) structure prediction confirmed that FloVR consists of seven transmembrane helices, and an extensive extracellular loop between helix II and helix III (Fig. 4a, b). Similar structures have been observed in other rhodopsins14,35, although a beta sheet is often present but was not found in FloVR. Phylogenetic analysis classifies FloVR as a new member of viral rhodopsin (VirR) group II. FloVR is most similar to Organic Lake Phycodnavirus rhodopsin II (OLPVRII) with an amino-acid identity of 52.56% (Fig. 4c). Like most proteins in this group, including OLPVRII, FloVR is characterized by a DTV-motif (i.e. Asp92, Thr96 and Val103) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6) which is associated with ion pumping activity9,12. The same motif was identified in viral environmental sequences at Station ALOHA in the North Pacific Gyre36 where FloV-SA2 was isolated.

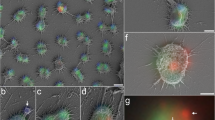

a 3D schematic (Ribbon diagram) of FloVR as predicted by AlphaFold2. Alpha (α) helices are colored in blue and the surface in gray. b Secondary structure prediction of FloVR. Key residues homologous to Organic Lake Phycodnavirus rhodopsin II (OLPVRII) are highlighted as: proton acceptor D92 (red circle) and donor E42 (purple circle), K217 forming a Schiff base link with retinal (pink circle), spectral tuning M100 (green diamond), putative channel pore F24, M28, and R29 (blue circles), and the pentameric structure E26, R36, H37, N40, and W225 (yellow circles). The seven transmembrane helices are indicated by the roman numerals and the putative membrane shown by the gray box. c Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic reconstruction of full viral rhodopsin (VirR) proteins (238 aa sites). One representative proteorhodopsin sequence (highlighted in black) was used as an outgroup. Various amino-acid motifs related to ion pump activity are indicated using standard single-letter amino-acid codes, along with different colored diamonds to make their distribution in the tree more obvious. Nodes with bootstrap support over 70% are shown as filled circles. The best-fit model for amino acid substitutions (LG + F + R4) was chosen according to the bayesian information criterion (BIC). Scale bar indicates amino-acid substitutions per site.

Full-length alignments of FloVR with OLPVRII indicated conservation of multiple residues playing a central role in rhodopsin function (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6). Recent studies demonstrated that the OLPVRII forms a pentamer with a symmetrical, bottle-like central channel (like a pore) with a narrow vestibule in the cytoplasmic part11. A similar pentameric structure was also observed for other microbial rhodopsins37. The lysine residue that provides the bond between Retinal Schiff Base (RSB) and retinal was found at position 217 in FloV-SA2, (K217) homologous to K195 in the OLPVRII11 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6). The structure of OLPVRII relies on a set of aa residues that are highly conserved in group II viral rhodopsins11. Glu26, Arg36, His37, Asn40, and Trp203 are responsible for the assembly of the pentameric structure and Phe24, Leu28, and Arg29 in the formation of the central channel in OLPVRII. Note that Leu28 can be replaced by methionine or isoleucine in some cases. These eight residues were also identified in FloVR with the exception of a methionine substitution into the position homologous to that of Leu28 of OLPVRII (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6). In addition, residues Asp75 and Glu42, which are the proton acceptor and the proton donor, respectively, in OLPVRII, are conserved in the FloVR protein sequence (Asp92 and Glu42 in FloVR) (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting a similar ion pumping mechanism. Bratanov et al.11 also highlighted an outward anion channel activity in OLPVRII which can functionally be closed by a hydrophobic gate formed by the Phe24 and Leu28 residues.

Therefore, the similarity of FloVR and OLPVRII in terms of overall structure and the presence of functionally important residues strongly suggests that FloVR is a functional protein acting as a pentameric light-gated ion channel with pumping activity. Finally, a full-length alignment of FloVR with other viral rhodopsins revealed that methionine is the predominant amino acid at position 100 (M83 in OLPVRII), corresponding to the site associated with spectral tuning (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 7). Spectral tuning refers to alterations in wavelength of maximum absorption by the rhodopsin molecule as a result of changes in the specific amino-acid present at this site36,37,38. In giant viruses, the most common variants observed include Leucine (L) and methionine (M) which have been suggested to absorb in the green region of the visible light spectrum36. Absorption activity in the green wavelengths has been experimentally demonstrated in both VirR groups11,12. While numerous studies have been carried out into the structure and molecular properties of viral rhodopsin, its function and the circumstances in which the virus requires it during infection are still poorly understood.

Discussion

Virus-host interactions tend to engender antagonistic coevolution, where viruses evolve to better exploit the host cell for their own replication, while hosts evolve to defend themselves against exploitation39,40,41. One locus of such coevolution is protein translation, which must be co-opted for viruses to succeed in replicating themselves. Viruses exhibit many strategies for commandeering cellular translation machinery, both by inhibiting translation of host transcripts and by preferentially promoting translation of viral transcripts42,43. It was recently discovered that viruses infecting bacteria26,44,45 and archaea46 encode certain ribosomal proteins, which may be another means of promoting the translation of viral transcripts, although the role of the viral ribosomal proteins is not known at this point. The only previous report of a ribosomal protein-like gene sequence in a eukaryovirus was for the Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus47, but in this case a sequence homologous to ribosomal protein S30 is oriented in antisense orientation and is not translated into a protein. Instead, the antisense transcript appears to act as a regulatory RNA suppressing transcription and translation of the corresponding host protein, and also inhibiting apoptosis27. With this work, we provide the first evidence that a eukaryovirus, FloV-SA2, encodes a ribosomal protein, eL40, and show that this gene is also present in viral metagenome-assembled genomes assigned to the order Imitervirales, most within the Mesomimiviridae family.

Ribosomes are formed through the assembly of various ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs) and proteins, yielding both large and small subunits (60S and 40S in eukaryotes). The eL40 protein is a component of the 60S subunit and usually occurs as a fusion protein with an N-terminal ubiquitin moiety48. In yeast, eL40 assembles into the 60S precursor at a late stage in the cytoplasm49 and is essential for ribosome assembly and cellular growth in Saccharomyces cerevisiae49 as well as the fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans50. Although eL40 is essential for ribosome assembly in yeast, a knockdown of this gene in human HeLa cells did not compromise ribosome biogenesis and cell viability, and only 7% of cellular transcripts required eL40 for translation, many of which are involved in stress response51. In contrast, cap-dependent translation of vesicular stomatitis virus transcripts was reliant on eL4051. The role of eL40 in regulation of translation suggests that viruses such as FloV-SA2 may encode this gene to preferentially promote translation of viral transcripts at the expense of cellular transcripts. If confirmed, this would represent a new mechanism by which eukaryoviruses control host translation.

In eukaryotes, eL40 is most often encoded as a ubiquitin-eL40 fusion protein. Studies in yeast indicate that the fused ubiquitin moiety is quickly cleaved from the translated protein, but its presence contributes to efficient incorporation of eL40 into the 60S subunit, likely by facilitating proper folding of eL40 as a cis-acting chaperone48. In contrast, the eL40 encoded by FloV-SA2, and by most of the GVMAGs, is not fused to ubiquitin, but is instead present as a stand-alone gene. This is not unique to these viruses, however, as bioinformatic analyses have shown that eL40 also occurs in stand-alone form in many archaea and some plants, animals, fungi, and protists48. Studies with knock-out mutants indicate that stand-alone versions of the gene will still support ribosome assembly when supplied at sufficiently high doses. Why some organisms and viruses lack the ubiquitin fusion and how this affects the function of eL40 is unknown. FloV-SA2 does encode for ubiquitin elsewhere in the genome, but there is no evidence that ubiquitin can facilitate folding in trans48 so the FloV-SA2 ubiquitin protein is likely involved in other processes. Enzymes playing a role in ubiquitin signaling have been reported in Nucleocytoviricota genomes19,52,53, and the high frequency and presence of multiple copies (paralogs) of ubiquitin in viral metagenomes suggest that such genes may be used to manipulate host defenses during infection. Since no eL40 homolog has been observed in bacteria, it makes sense that this protein has never been reported in phage genomes30. Likewise, the most common ribosomal protein in phage genomes in aquatic environments is bS2126,44, which is restricted to bacteria30. Although eL40 and bS21 are not homologous and occur in different ribosomal subunits, one commonality is that both are assembled into ribosomes at a late stage49,54. There are several hypotheses about the function of ribosomal proteins encoded by phages. Al-Shayeb et al. proposed that the bS21 protein of the host could be substituted by the viral version, enabling them to favor the translation of viral mRNA over bacterial mRNA45. Others suggested that ribosomal protein may contribute to specialized translation and/or evasion of bacterial defenses55. The gene for bS21 is generally co-located with those coding for proteins involved in virion structure and assembly and is likely transcribed during late-stage replication along with core structural proteins. This led to the suggestion that bS21 may be required during late-stage replication, and/or is packaged in the capsid to efficiently modulate translation during infection44. In the FloV-SA2 genome, eL40 appears to be localized at the 5’-end, co-locating with numerous genes with only putative functions or without hits in databases (Supplementary Table 1). Additional research will be needed to examine the function of viral eL40 genes and whether they play a comparable role to phage bS21 genes. Overall, our findings highlight that the acquisition of these proteins is the result of a complex evolutionary process between hosts and viruses, likely arising from multiple horizontal transfer events as well as duplication events, like other translation proteins found in Nucleocytoviricota2,24,25,56. Our analyses show that eL40 is actively transcribed in the oceans and appears to be under purifying selection pressure. These results suggest that the acquisition of this protein in viruses is functional and plays a role in the infection cycle that has yet to be determined. This work expands the scope of cellular processes known to be encoded in viral genomes.

Materials and methods

Eukaryotic phytoplankton isolation and identification

Florenciella sp. strain UHM3020 (class Dictyochophyceae; equivalent to strain AL-45-004C in Schvarcz, 201857) was isolated from seawater samples collected at 45 meters from an oligotrophic open-ocean site (Station ALOHA58, 22°45’ N, 158°00’ W), in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. Seawater samples were enriched with Keller (K) medium59 and incubated in tubes at 24–26 °C on a 12:12 light:dark cycle with approximately 30–100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 irradiance. Unialgal cultures were then isolated by a serial dilution-to-extinction approach. Florenciella sp. UHM3020 was further identified by small subunit ribosomal RNA (18S rRNA) gene sequencing. For this purpose, Florenciella cells were harvested by centrifuging approximately 25 mL of culture at 4000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. DNA was extracted from the pellets using the MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit (Epicentre). The 18S rRNA gene (~1700 bp) was amplified by PCR with the Roche ExpandTM High Fidelity PCR System (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) using oligonucleotide forward primer 5’-ACCTGGTTGATCCTGCCAG-3’ and reverse primer 5’-TGATCCTTCYGCAGGTTCAC-3’60. The PCR product was then cloned using the TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Two to three colonies were grown in CirclegrowTM medium (MP Biomedicals, Irvine, CA, USA) and extracted using the Zyppy Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Zymo Research). The near-full-length gene was sequenced using primers M13f, M13r, 502f, and 1174r61.

Virus isolation and host range

The FloV-SA2 virus was isolated by challenging Florenciella sp. UHM3020 with a seawater sample collected from Station ALOHA at a depth of 25 meters. Forty liters of seawater was filtered through 0.8 μm pore size filters to remove larger cells while minimizing losses of large viruses. Virions (along with other cells, particles, and high molecular weight soluble material) in the filtrate were concentrated by tangential flow filtration (TFF; Millipore Pellicon 2 Mini System) using 30 kDa nominal molecular weight limit (NMWL) filters. The concentrate was amended with nutrients to match K medium and added to a healthy Florenciella culture. The challenged culture was observed for 1–2 weeks for signs of cell lysis, and multiple additional rounds of lysis of fresh cultures were used to confirm consistent lytic activity. The lysate was then stored at 4°C and propagated at least once per month by challenging new cells (1–10% v/v of lysate added per challenge). Finally, 2–3 rounds of dilution-to-extinction were performed in 96-well plates to create a clonal stock of the putative virus. The host range of FloV-SA2 was investigated by adding 1% lysate to exponentially growing cultures of diverse dictyochophyte isolates and monitoring for lysis via Chl a autofluorescence over two weeks.

Gradient purification of the virus

Twenty liters of viral lysate was concentrated to 300 mL by TFF as described above, then clarified by centrifugation (4000 RCFavg for 30 min) followed by filtration (0.45 µm Sterivex, Millipore) to remove debris and some bacteria. Viruses were further concentrated to ca. 0.5 mL by centrifugal ultrafiltration (30 kDa Centricon 70; Millipore). Concentrated virus was adjusted to 1.45 g mL−1 final density and 13 mL final volume with CsCl, then incorporated as the middle layer of a three-layer step gradient (bottom: 9.8 mL of 1.60 g mL−1; middle: 13 mL of 1.45 g mL−1, top: 14.5 mL of 1.20 g mL−1) and centrifuged at 25,000 rpm (82,740 RCFavg) for 47.3 h in swinging bucket rotor (SW 28, Beckman Coulter) to form a continuous gradient62. The middle third of the gradient with visible bands was harvested in high-resolution fractions (300 µl each) with a piston fractionator (Gradient Station; BioComp Instruments Ltd.). To identify virus-containing fractions, subsamples of select fractions were checked by epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I63 and examined in more detail by electron microscopy (below). Fraction densities were determined by weighing a known volume measured with a positive-displacement pipet62.

The virus peak fractions (1.389 to 1.411 g mL−1) were pooled, concentrated and exchanged into SM buffer (100 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 50 mM Tris•Cl; pH 8) by three rounds of dilution and centrifugal ultrafiltration (30 kDa, Amicon Ultra 15, Millipore), then recovered in 1 mL of SM. To further improve separation between virus and residual contaminants. The resulting virus sample was layered on top a pre-formed continuous CsCl gradient (37.6 mL; 1.215–1.585 g mL−1) and centrifuged 20,000 rpm (53,740 RCFavg) for 18.5 h in a swinging bucket rotor (SW 28). The gradient was fractionated and the fractions examined as above. The density of the peak fraction was measured as noted above. Five fractions encompassing the virus peak were pooled and exchanged in SM buffer by centrifugal ultrafiltration (4 × 500 µL; 100 kDa Amicon Ultra, Millipore), then recovered in 150 µL for subsequent DNA extraction.

Electron microscopy

Virion morphology was examined by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). A portion (2 µL) of a CsCl gradient fraction in the virus peak was exchanged into SM buffer by three rounds of centrifugal ultrafiltration, then adsorbed for 45 s to grids (carbon-stabilized formvar support on a 200-mesh copper) that had been rendered hydrophilic by glow discharge. Sample was wicked with filter paper, stained with 0.5% uranyl acetate for 45 s, wicked again, rinsed once with 10 µL water, then immediately wicked and air dried before examination in a Hitachi HT7700 electron microscope.

Nucleic acid extraction, genome sequencing, and assembly

DNA was extracted from CsCl gradient-purified virions (Masterpure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit; LGC Biosearch Technologies) and quantified by fluorometry (QuantIT DNA High Sensitivity kit; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Preliminary genome sequencing was performed using Illumina Sequencing at the Georgia Genomics and Bioinformatics Core (previously Georgia Genomics Facility) at the University of Georgia. Short-read libraries were prepared using Nextera XT and sequenced by NextSeq (150-bp paired-ends). Then, a long-read library was constructed using PacBio sequencing at the University of Washington PacBio Sequencing Services. Genomic DNA from multiple distantly related viruses was pooled in a single sample for sequencing, after which virus-specific reads were extracted from the total dataset based on BLAST similarity to draft genomes assembled from Illumina data. The PacBio sample was created by pooling RNase-treated genomic DNA extracts, followed by concentrating the DNA using a centrifugal ultrafilter (30 kDa NMWL; Millipore Amicon Ultra-0.5) and cleaning the sample using the PowerClean Pro DNA Clean-Up Kit (MO BIO). The FloV-SA2 genome was assembled from PacBio sequencing reads using Canu v1.064 and polished using a combination of pbalign v0.2.0.141024 and Quiver v2.0.065.

Genes prediction and functional annotation

Coding sequences (CDSs) were predicted using Prokka v1.14.566 (parameters --kingdom Virus --addgenes --cdsrnaolap --addmrna) and tRNAs were predicted using tRNAscan-SE v2.0.267,68. First, protein-coding genes were annotated using the databases implemented in Prokka with the following parameters: E-value, 1e-5; and genetic code, standard (--gcode 1). Functional annotations were performed using a BLASTp search using Diamond (v2.1.4)69 (an E-value of <1e-5 and keeping only the best hit) against the NCBI Refseq database and using the InterProScan v544-79.0 program70. Taxonomic affiliation was associated for each protein accession using Entrez Direct (EDirect) v10.371.

Survey of the ubiquitin-60S ribosomal protein eL40

In order to identify eL40 homologs in the Florenciella sp. host genome, a tBLASTn search was performed applying an E-value of 1 × 10−5. The three-dimensional (3D) structural proteins of the ribosomal protein eL40, in the FloV-SA2 genome and its host genome, have been obtained through ColabFold72 and visualized using ChimeraX73.

After the discovery of the eL40 protein in the FloV-SA2 genome, we performed BLASTp searches using Diamond (v2.1.4)69 to find additional putative viral and protistan sequences for further analysis. While eL40 is usually an N-terminal ubiquitin-fused protein in eukaryotic genomes, it was found decoupled from ubiquitin in the FloV-SA2 genome. Therefore, we used both eL40 and ubiquitin query sequences from FloV-SA2 to find related sequences. This survey was performed against different databases including the GVMAGs V174, metagenome-assembled genomes of Nucleocytoviricota generated by Moniruzzaman et al. (2020)4, the Global Ocean Eukaryotic Viral database (GOEV)75 and NCBI nr database using Diamond V2.1.469 with an E-value of 1 × 10−3. All the best blast hits obtained were merged and de-replicated. In addition, a BLASTp search was carried out against the cultivated Florenciella sp. host genome, Tara Oceans Eukaryotic Genomes (MAGs and SAGs) database34 and NCBI nr database with an E-value of 1 × 10−3 and excluding Fungi (taxid:4751), Bacteria (taxid:2) and plants (taxid:3193) groups. For metagenomes with an eL40 protein sequence larger than the expected size, an additional search was carried out using NCBI Batch CD-search tool with an E-value of 1 × 10−3 to investigate the function of other putative conserved domains fused to the ribosomal protein. GVMAGs expressed in metatranscriptomic datasets from California coastal waters reported by Ha et al.31 were manually compared with those recovered from the three viral metagenomes used previously containing eL40 and/or ubiquitin protein in this study.

In order to conduct further phylogenetic analysis, a first cutoff was applied to the total of 336 eL40 sequences recovered from the BLASTp-search of NCBI nr database as well as viral and protistan MAGs. For any fusion proteins, the ubiquitin sequence was trimmed from the protein sequence, reducing the alignment of a total of 53 aa sites. Furthermore, to avoid long branches with weak support, highly divergent sequences were excluded, as were some unusually short sequences ( < 50% of the 53 aligned aa sites), and others that were fused to protein domains other than ubiquitin (n = 20; Supplementary Table 5). Of the 336 eL40 sequences, 306 have been retained to build phylogenetic trees, described in the section below. The reference set of the closest relative isolated eukaryotes (n = 93) used for the phylogenetic tree reconstruction, has been listed in supplementary data (Supplementary Table 2d). The ratio of non-synonymous to synonymous substitutions of the eL40 coding sequence was computed using KaKs_Calculator 3.076. For this purpose, the entire dataset was divided into sub-datasets of sequences with a percentage protein identity more than 70%. KaKs_Calculator 3.0 was run on each nucleotide alignment group separately through a model averaging (MA) method.

Rhodopsin analysis

Predicted 3D structure of a rhodopsin protein in the FloV-SA2 and the Florenciella sp. host genomes were generated using ColabFold72 and visualized using ChimeraX73. Putative transmembrane domains were predicted using TMHMM-2.077 and secondary (2D) structure visualized with Protter (v.1.0)78 with manual editing.

Phylogenetic tree

Seven Nucleocytoviricota marker genes (SFII, RNAPL, PolB, TFIIB, TopoII, A32, and VLTF3) were identified using a Python script (ncldv_markersearch tool) developed by Moniruzzaman et al.4. Then, phylogenetic reconstruction was performed based on the concatenated full-length sequences of these proteins. Before concatenation, proteins were aligned with MAFFT v7.3.13 (L-INS-i algorithm)79,80. Protein alignment was then automatically trimmed with a cutoff of 50% gaps using Goalign v0.3.281. A visual inspection was then carried out to ensure no obvious bias for further phylogenetic tree construction. For ubiquitin-60S ribosomal protein eL40, all protein sequences containing the eL40 protein domain, after cutoff, were aligned and trimmed using the same parameters as described previously, retaining only the eL40 domain (53 aa sites) (n = 306) for further phylogenetic analysis. To this dataset we have added a sequence more divergent, Saccharomyces cerevisiae (GenBank Acc. GAX70831.1), as an outgroup to root the tree. Saccharomyces cerevisiae was selected as an outgroup for the phylogenetic analysis because it is a well-characterized 60S ribosomal protein L40 with high similarity to the sequences of the Florenciella host strain (88.2% of amino-acid identity) and FloV-SA2 (82.20% of amino-acid identity), providing a reliable reference point for rooting the tree. Viral rhodopsin proteins detected in environmental samples were extracted (n = 40) from Needham et al.12, aligned and trimmed as described previously. All phylogenetic trees were reconstructed based on the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method using IQ-TREE v2.0.682 and the best model was chosen (parameter -m MFP) according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). The branch support values were computed from 1000 replicates for the Shimodaira-Hasegawa (SH)-like approximation likelihood ratio test83 and 1,000 ultrafast bootstrap approximation (UFBoot)84. The phylogenetic tree was visualized using tree visualization using iTOL v6.985.

Data availability

The authors declare that the main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article, its Supplementary information, or publicly accessible online databases. The FloV-SA2 genome sequence was deposited in GenBank under accession number PP542043. The ubiquitin-60S ribosomal protein eL40 gene sequence encoded in the Florenciella sp. host genome was deposited in GenBank with accession number PP665604. All data including alignments and phylogenies are available from Figshare: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.25662771.

References

Aylward, F. O., Moniruzzaman, M., Ha, A. D. & Koonin, E. V. A phylogenomic framework for charting the diversity and evolution of giant viruses. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001430 (2021).

Philippe, N. et al. Pandoraviruses: amoeba viruses with genomes up to 2.5 Mb reaching that of parasitic eukaryotes. Science 341, 281–286 (2013).

Legendre, M. et al. Pandoravirus Celtis illustrates the microevolution processes at work in the giant Pandoraviridae Genomes. Front. Microbiol. 10, 430 (2019).

Moniruzzaman, M., Martinez-Gutierrez, C. A., Weinheimer, A. R. & Aylward, F. O. Dynamic genome evolution and complex virocell metabolism of globally-distributed giant viruses. Nat. Commun. 11, 1710 (2020).

Blanc-Mathieu, R. et al. A persistent giant algal virus, with a unique morphology, encodes an unprecedented number of genes involved in energy metabolism. J. Virol. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.02446-20 (2021).

Weynberg, K. D., Allen, M. J., Ashelford, K., Scanlan, D. J. & Wilson, W. H. From small hosts come big viruses: the complete genome of a second Ostreococcus tauri virus, OtV-1. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2821–2839 (2009).

Weynberg, K. D., Allen, M. J., Gilg, I. C., Scanlan, D. J. & Wilson, W. H. Genome sequence of Ostreococcus tauri virus OtV-2 throws light on the role of picoeukaryote niche separation in the ocean▿. J. Virol. 85, 4520–4529 (2011).

Moreau, H. et al. Marine prasinovirus genomes show low evolutionary divergence and acquisition of protein metabolism genes by horizontal gene transfer. J. Virol. 84, 12555–12563 (2010).

Yutin, N. & Koonin, E. V. Proteorhodopsin genes in giant viruses. Biol. Direct 7, 34 (2012).

Philosof, A. & Béjà, O. Bacterial, archaeal and viral-like rhodopsins from the Red Sea. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 475–482 (2013).

Bratanov, D. et al. Unique structure and function of viral rhodopsins. Nat. Commun. 10, 4939 (2019).

Needham, D. M. et al. A distinct lineage of giant viruses brings a rhodopsin photosystem to unicellular marine predators. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 20574–20583 (2019).

Rozenberg, A. et al. Lateral gene transfer of anion-conducting channelrhodopsins between green algae and giant viruses. Curr. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.09.056 (2020).

Zabelskii, D. et al. Structure-based insights into evolution of rhodopsins. Commun. Biol. 4, 1–12 (2021).

Monier, A. et al. Horizontal gene transfer of an entire metabolic pathway between a eukaryotic alga and its DNA virus. Genome Res. 19, 1441–1449 (2009).

Vardi, A. et al. Viral glycosphingolipids induce lytic infection and cell death in marine phytoplankton. Science 326, 861–865 (2009).

Kijima, S. et al. Discovery of viral myosin genes with complex evolutionary history within plankton. Front. Microbiol. 12, 683294 (2021).

Da Cunha, V. et al. Giant viruses encode actin-related proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol. 39, msac022 (2022).

Schvarcz, C. R. & Steward, G. F. A giant virus infecting green algae encodes key fermentation genes. Virology 518, 423–433 (2018).

Claverie, J.-M. & Abergel, C. Mimivirus: the emerging paradox of quasi-autonomous viruses. Trends Genet. 26, 431–437 (2010).

Aylward, F. O. et al. Taxonomic update for giant viruses in the order Imitervirales (phylum Nucleocytoviricota). Arch. Virol. 168, 283 (2023).

Raoult, D. et al. The 1.2-megabase genome sequence of mimivirus. Science 306, 1344–1350 (2004).

Bajrai, L. H. et al. Isolation of yasminevirus, the first member of Klosneuvirinae Isolated in coculture with vermamoeba vermiformis, demonstrates an extended arsenal of translational apparatus components. J. Virol. 94, e01534-19 (2019).

Abrahão, J. et al. Tailed giant Tupanvirus possesses the most complete translational apparatus of the known virosphere. Nat. Commun. 9, 749 (2018).

Schulz, F. et al. Giant viruses with an expanded complement of translation system components. Science 356, 82–85 (2017).

Mizuno, C. M. et al. Numerous cultivated and uncultivated viruses encode ribosomal proteins. Nat. Commun. 10, 752 (2019).

Mourtada-Maarabouni, M., Kirkham, L., Farzaneh, F. & Williams, G. T. Regulation of apoptosis by fau revealed by functional expression cloning and antisense expression. Oncogene 23, 9419–9426 (2004).

Moniruzzaman, M. et al. Virologs, viral mimicry, and virocell metabolism: the expanding scale of cellular functions encoded in the complex genomes of giant viruses. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 47, fuad053 (2023).

Yau, S. et al. Virophage control of antarctic algal host–virus dynamics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 6163–6168 (2011).

Lecompte, O., Ripp, R., Thierry, J., Moras, D. & Poch, O. Comparative analysis of ribosomal proteins in complete genomes: an example of reductive evolution at the domain scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 5382–5390 (2002).

Ha, A. D., Moniruzzaman, M. & Aylward, F. O. High transcriptional activity and diverse functional repertoires of hundreds of giant viruses in a coastal marine system. mSystems https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00293-21 (2021).

Lauersen, K. J. et al. Peroxisomal microbodies are at the crossroads of acetate assimilation in the green microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Algal Res. 16, 266–274 (2016).

Boyle, N. R., Sengupta, N. & Morgan, J. A. Metabolic flux analysis of heterotrophic growth in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PLoS ONE 12, e0177292 (2017).

Delmont, T. O. et al. Functional repertoire convergence of distantly related eukaryotic plankton lineages abundant in the sunlit ocean. Cell Genomics 2, 100123 (2022).

Strauss, J. et al. Plastid-localized xanthorhodopsin increases diatom biomass and ecosystem productivity in iron-limited surface oceans. Nat. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-023-01498-5 (2023).

Olson, D. K., Yoshizawa, S., Boeuf, D., Iwasaki, W. & DeLong, E. F. Proteorhodopsin variability and distribution in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. ISME J. 12, 1047–1060 (2018).

Brown, L. S. & Ernst, O. P. Recent advances in biophysical studies of rhodopsins - oligomerization, folding, and structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1865, 1512–1521 (2017).

Man, D. et al. Diversification and spectral tuning in marine proteorhodopsins. EMBO J. 22, 1725–1731 (2003).

Martiny, J. B. H., Riemann, L., Marston, M. F. & Middelboe, M. Antagonistic coevolution of marine planktonic viruses and their hosts. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 6, 393–414 (2014).

Frickel, J., Sieber, M. & Becks, L. Eco-evolutionary dynamics in a coevolving host–virus system. Ecol. Lett. 19, 450–459 (2016).

Friman, V.-P. & Buckling, A. Effects of predation on real-time host–parasite coevolutionary dynamics. Ecol. Lett. 16, 39–46 (2013).

Miller, C. M., Selvam, S. & Fuchs, G. Fatal attraction: the roles of ribosomal proteins in the viral life cycle. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 12, e1613 (2021).

Wang, X., Zhu, J., Zhang, D. & Liu, G. Ribosomal control in RNA virus-infected cells. Front. Microbiol. 13, 1026887 (2022).

Chen, L.-X. et al. Phage-encoded ribosomal protein S21 expression is linked to late-stage phage replication. ISME Commun. 2, 1–10 (2022).

Al-Shayeb, B. et al. Clades of huge phages from across Earth’s ecosystems. Nature 578, 425–431 (2020).

Liu, Y. et al. Diversity, taxonomy, and evolution of archaeal viruses of the class Caudoviricetes. PLoS Biol. 19, e3001442 (2021).

Michiels, L., Van der Rauwelaert, E., Van Hasselt, F., Kas, K. & Merregaert, J. fau cDNA encodes a ubiquitin-like-S30 fusion protein and is expressed as an antisense sequence in the Finkel-Biskis-Reilly murine sarcoma virus. Oncogene 8, 2537–2546 (1993).

Martín-Villanueva, S., Gutiérrez, G., Kressler, D. & de la Cruz, J. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins and domains in ribosome production and function: chance or necessity? Int J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4359 (2021).

Fernández-Pevida, A., Rodríguez-Galán, O., Díaz-Quintana, A., Kressler, D. & de la Cruz, J. Yeast ribosomal protein L40 assembles late into precursor 60 S ribosomes and is required for their cytoplasmic maturation. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 38390–38407 (2012).

Zhao, J. et al. Ribosomal protein L40e fused with a ubiquitin moiety is essential for the vegetative growth, morphological homeostasis, cell cycle progression, and pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. Front. Microbiol. 11, 570269 (2020).

Lee, A. S.-Y., Burdeinick-Kerr, R. & Whelan, S. P. J. A ribosome-specialized translation initiation pathway is required for cap-dependent translation of vesicular stomatitis virus mRNAs. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 324–329 (2013).

Iyer, L. M., Balaji, S., Koonin, E. V. & Aravind, L. Evolutionary genomics of nucleo-cytoplasmic large DNA viruses. Virus Res. 117, 156–184 (2006).

Lant, S. & Maluquer de Motes, C. Poxvirus interactions with the host ubiquitin system. Pathogens 10, 1034 (2021).

Chen, S. S. & Williamson, J. R. Characterization of the ribosome biogenesis landscape in E. coli using quantitative mass spectrometry. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 767–779 (2013).

Watson, Z. L. et al. Structure of the bacterial ribosome at 2 Å resolution. eLife 9, e60482 (2020).

Andreani, J. et al. Orpheovirus IHUMI-LCC2: a new virus among the giant viruses. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2643 (2018).

Schvarcz, C. R. Cultivation And Characterization Of Viruses Infecting Eukaryotic Phytoplankton From The Tropical North Pacific Ocean (2018).

Karl, D. M. & Lukas, R. The Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT) program: background, rationale and field implementation. Deep Sea Res. Part II: Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 43, 129–156 (1996).

Keller, M. D., Selvin, R. C., Claus, W. & Guillard, R. R. L. Media for the culture of oceanic ultraphytoplankton1,2. J. Phycol. 23, 633–638 (1987).

Moon-van der Staay, S. Y., De Wachter, R. & Vaulot, D. Oceanic 18S rDNA sequences from picoplankton reveal unsuspected eukaryotic diversity. Nature 409, 607–610 (2001).

Worden, A. Picoeukaryote diversity in coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 43, 165–175 (2006).

Lawrence, J. E. & Steward, G. F. Manual of Aquatic Viral Ecology (eds. Wilhelm, S., Weinbauer, M. & Suttle, C.) 166–181 (American Society of Limnology and Oceanography, 2010).

Patel, A. et al. Virus and prokaryote enumeration from planktonic aquatic environments by epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I. Nat. Protoc. 2, 269–276 (2007).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736 (2017).

Chin, C.-S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569 (2013).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Schattner, P., Brooks, A. N. & Lowe, T. M. The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W686–689 (2005).

Chan, P. P. & Lowe, T. M. tRNAscan-SE: searching for tRNA genes in genomic sequences. Methods Mol. Biol. 1962, 1–14 (2019).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2015).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Kans, J. Entrez Direct: E-Utilities on the Unix Command Line. Entrez Programming Utilities Help [Internet] (National Center for Biotechnology Information (US), 2021).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Pettersen, E. F. et al. UCSF ChimeraX: structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 30, 70–82 (2021).

Schulz, F. et al. Giant virus diversity and host interactions through global metagenomics. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-1957-x (2020).

Gaïa, M. et al. Mirusviruses link herpesviruses to giant viruses. Nature 616, 783–789 (2023).

Zhang, Z. KaKs_Calculator 3.0: calculating selective pressure on coding and non-coding sequences. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 20, 536–540 (2022).

Krogh, A., Larsson, B., von Heijne, G. & Sonnhammer, E. L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 305, 567–580 (2001).

Omasits, U., Ahrens, C. H., Müller, S. & Wollscheid, B. Protter: interactive protein feature visualization and integration with experimental proteomic data. Bioinformatics 30, 884–886 (2014).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT Multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Lemoine, F. & Gascuel, O. Gotree/Goalign: toolkit and Go API to facilitate the development of phylogenetic workflows. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 3, lqab075 (2021).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Guindon, S. et al. New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321 (2010).

Hoang, D. T., Chernomor, O., von Haeseler, A., Minh, B. Q. & Vinh, L. S. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2018).

Letunic, I. & Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL): an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Bioinformatics 23, 127–128 (2007).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NSF awards OCE-2129697 and RII Track-2 FEC 1736030 (to G.F.S. and K.F.E.) and Simons Foundation award 566853 (to K.F.E.). We thank Yoshimi M. Rii for providing the Florenciella UHM3020 host culture and Tina M. Weatherby at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa Biological Electron Microscope Facility for their assistance and guidance with electron microscopy procedures. We also thank the personnel in the Hawai’i Ocean Time-series program (NSF award 12-60164) for assistance with water collection. The technical support and advanced computing resources from the University of Hawaii Information Technology Services – Cyberinfrastructure, funded in part by the National Science Foundation CC* awards # 2201428 and # 2232862, are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.T., K.F.E. and G.F.S. conceptualized the project; K.F.E. and G.F.S. acquired funding; J.T., K.F.E., G.F.S., C.R.S. and K.A.M. conducted the investigations; J.T., K.F.E., G.F.S. and C.R.S. provided resources and supervised the project; J.T., K.F.E. and G.F.S. wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Thomy, J., Schvarcz, C.R., McBeain, K.A. et al. Eukaryotic viruses encode the ribosomal protein eL40. npj Viruses 2, 51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-024-00060-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44298-024-00060-2

This article is cited by

-

Revisiting giant virus-host dynamics in brown algae: old stories and new perspectives

The EMBO Journal (2026)

-

A deep dive into giant viruses

npj Viruses (2025)

-

Cellular souvenirs in viral luggage

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2025)