Abstract

A changing climate, with intensifying precipitation may contribute to increasing failures of dams by overtopping. We present the first analysis of rainfall sequences and events associated with recent hydrologic failures of 552 dams in the United States. We find that the maximum 1-day rainfall associated with failure was often not extreme compared to dam spillway design criteria, even when accounting for rainfall statistics changing with time at each site. However, the combination of the total rainfall 5 to 30 days prior and the maximum 1-day rainfall associated with dam failure is rare. Persistent atmospheric circulation patterns that lead to recurrent rainfall events, rather than just more moisture in the atmosphere is a possible reason. The probability of these compound precipitation risks has increased across much of the country. With over 90,000 aging dams still in service, the increasing likelihood of intense rainfall sequences raises concerns about future dam failures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increase in the rate of dam failures has led to growing concerns about the state of aging dams in the United States (US) and elsewhere. The decadal rate of dam failures has been increasing, especially since the 1970s1, and this trend appears to persist (Supplemental Fig. 1a). The deteriorating state of dam maintenance, coupled with a changing climate by more extreme rainfall events, could precipitate failures due to overtopping2,3,4,5. The US National Inventory of Dams (NID) contains over 92,000 dams with an average age of 60 years6. Of these, approximately 25,000 are classified as posing a high or significant hazard on failure, and 74% of these dams (18,657) are rated as fair, poor, unsatisfactory, or not rated for their condition. Since 2000, there have been reports of 630 dam failures in the contiguous United States (CONUS) attributed to hydrologic factors7. The conventional dam design criteria require the spillway to be designed to handle the “inflow design flood”, which is usually identified as the “Probably Maximum flood” (PMF) using the “Probable Maximum Precipitation” (PMP)8. These criteria are typically “event” based, where the event has a duration of 1 to 24 hours9 under conditions of extreme antecedent moisture. Most large dams were designed to withstand extreme floods with an implied return period ranging from 104 to 107 years10,11, as estimated by the PMF approach.

However, dam failures in the last 20 years and many near failures suggest more modest return periods for failure, i.e., higher failure risks. For example, climate conditions during the Oroville spillway failure in 201712, as well as during the Michigan dam failures in 202013, were shown to be relatively moderate. Notably, of the 630 recorded failures, 18 were primarily induced by snowmelt during moderate rainfall events7. The narrative of many of the recent dam failures, including Oroville, the Michigan dams, and the Libyan dam failures in 202314, highlights two main factors: (1) the overtopping failure was associated with multiple prior rainfall events that led to “watershed memory” or high “antecedent soil moisture”, and to a full reservoir at the time of the last rainfall event that led to overtopping, and (2) reservoir operators invariably kept the reservoir relatively full due to operational requirements anticipating future water demands, or to meet regulatory requirements, and hence there was low flood storage capacity when the overtopping storm occurred. These conditions fall well below the assumed design criteria that are designed using extreme storm scenarios of some duration under extreme antecedent moisture conditions as the causal factor15.

The frequency, intensity, and clustering of extreme rainfall events vary with inter-annual (e.g., ENSO) and decadal climate variations, and anthropogenic climate change16,17,18,19. Do these variations, coupled with aging and poorly maintained dams lead to significant increases in the risk of overtopping and dam failures? Several studies have shown that the current hydrologic infrastructure design standards are insufficient, given the substantial increase in the frequency of extreme meteorological events20,21. Consequently, an increased likelihood of hydrological failures of dams is anticipated across various regions of the US in response to the changing climate22,23. Nonetheless, to date, no systematic analysis has addressed this critical question on a continental or global scale, partly due to an underestimation of the issue’s seriousness and the complexity involved in modeling hydroclimatic conditions alongside human behavior (reservoir operation). Such an analysis requires assumptions as to operating rules and condition of the dams that are hard to validate in large-scale studies. Extensive data on rainfall are available for the US, and how changing rainfall extremes affect dam failure is an open question.

Numerous studies have provided evidence that extreme precipitation events have been increasing both in intensity and frequency in large parts of the US24,25,26,27. Climate projections suggest this trend will persist as global warming continues, as predicted by the Clausius-Clapeyron relationship24,28. However, no corresponding analysis of a sequence of rainfall events preceding a large rainfall event has been done at a continental scale. A persistent atmospheric circulation regime can bring recurrent storms into a region, culminating in an extreme flood peak and volume29,30.

We consider three main questions: 1) What primarily triggered recent hydrologically induced-dam failures: a sequence of high rainfall events, a single extreme rainfall event, or a combination of both? 2) How has the likelihood of these factors evolved across the CONUS? 3) What does it imply for the changing risk of dam failure in different regions of the country relative to the data that may have been available at the time of dam design? We explore these questions using data for the 552 recent dams whose failure was attributed to hydrologic factors, but excluding snow-related failures, and find that extreme rainfall event sequences rather than an extreme 1-day rainfall are more common at failure. The trends in both the annual one- and multi-day and joint precipitation events across the country were analyzed to provide an indication of the possible regional exposure of CONUS dams to such events.

Results

Return periods of 1-day and precedent rainfalls during dam failures

We addressed the first question, i.e., whether the event rainfall or the preceding multi-day rainfall, or a combination of the two, was extreme at the time of failure of the 552 US dams that have failed since 2000 using a blended 1901-2021 20CRv3-ERA5 reanalysis rainfall dataset. At each site, the dam failure event rainfall’s return period was assessed using an analysis of the maximum 1-day rainfall preceding dam failure (A*). The return period was evaluated using the annual maximum daily rainfall (A) for the full period of record using a non-stationary GEV model with a linear temporal trend in the scale and location parameters (see Methods for details). A similar analysis was performed for the cumulative rainfall (K) for the k = 5 and 30 days preceding failure, using a non-stationary Gamma distribution with linear time trends for the location and scale parameters, applied to the annual maximum rainfall, Kk, for each of those durations and for the joint event (A*, K*) associated with the failure event.

We find that A* associated with failure was usually a moderate event, often with a return period of under 10 years, and around 100-1,000 years in a few cases (Fig. 1). These are much smaller events in most cases than would be associated with a PMP or PMF used as the dam failure design criterion. The preceding 5- or 30-day rainfall (K5* or K30*) also had similar to slightly larger return periods, but the joint event (A*, K5*) or (A*, K30*) was usually much more unusual. For instance, in the state of South Carolina, over 40 dam failures occurred in October 2015, attributed to persistent heavy rainfall spanning several days31 and a high 1-day rainfall. This is seen in Fig. 1d, as a cluster of dam incidents characterized by notably high return periods for the joint occurrences of A* and K5*. Another cluster featuring an extreme joint occurrence of A* and K30* is observed across the states of New Jersey and New York, associated with the historical floods caused by Hurricane Irene in 2011. In this case, prolonged heavy rainfall also occurred approximately 15 days before the hurricane32,33. Consequently, the indication is that the joint occurrence of a moderately rare 1-day rainfall event coupled with a sequence of rare wet events preceding was a factor in many of the dam failures. This compound risk of persistent high rainfall is often associated with a persistent atmospheric circulation pattern leading to recurrent high rainfall events in a region29,30.

Return periods of (a) 1-day maximum precipitation, A* (b) 5-day precedent precipitation total, K5* (c) 30-day precedent precipitation total, K30* (d) joint occurrence of 1-day maximum precipitation and 5-day precedent precipitation total, (A*, K5*), and (e) joint occurrence of 1-day maximum precipitation and 30-day precedent precipitation total (A*, K30*) observed dam failures at each location. The models fit for the probability distributions (GEV for A, Gamma for K5 and K30, and best copula for (A, K5) and (A, K30)) consider linear time trends fit independently to the 1901-2021 20CRv3-ERA5 reanalysis data at each dam location (see Methods for details), and the exceedance probabilities are evaluated from the local model at the year of failure of each dam.

Return periods of 1-day and precedent rainfalls under non-stationarity

The second question was whether the return period of the precipitation associated with the failure event had changed significantly from the time of design of the dam to the time of failure. A challenge with this analysis was that the date of construction was available for only 497 of the dams that had failed. A comparison of the exceedance probabilities of A*, K5*, and K30* for the dam failure event, evaluated for the year of failure versus the year of design using the at-site non-stationary models across the entire group of 497 dams does not suggest a significant change in these probabilities across these time periods (Fig. 2 and Supplemental Figs. 2 and 3). This is interesting given the widespread published examples of increases in the frequency of extreme daily and sub-daily rainfall21. However, there are clusters of dam sites across the CONUS where the exceedance probabilities of A*, K5*, and K30* appear to have increased and where they have decreased – e.g., in Fig. 2, the exceedance probabilities of A* have been increasing (red colored) across a cluster of dams in the northeast with a mean age of approximately 98 years, while the exceedance probabilities of K5* and K30* have been decreasing (blue colored) in some dams in the south with a mean age of around 58 years. There is a large variation in these results that may mask the change at the national level. A widespread change in the hydroclimatic risk associated with the failure event is not evident, perhaps because persistent rainfall events are implicated in the failure. In most cases, where the compound events (A*, K*) were rare at the time of failure, they were also rare at the time of design. The clustering of floods at inter-annual to decadal time scales has been demonstrated as an issue for flood risk and trend analysis34,35.

a Comparison between the distributions of return periods estimated at the time of dam incidents and those estimated at the time of dam construction. Here, J5* and J30* denotes the joint occurrence (A*, K5*) and joint occurrence (A*, K30*), respectively. The box represents the interquartile range, while the whiskers represent the range of values within 1.5 times the interquartile range beyond the first and third quartiles. b Ratio of return periods estimated at the time of dam incidents to those estimated at the time of dam constructions for A*, (c) for K5*, (d) for K30*, (e) for joint occurrence of A* and K5*, and (f) for joint occurrence of A* and K30*. Dams lacking construction-year information are marked with an ‘X’ symbol.

Recent trends in precipitation extremes and climate-induced dam failure potential across the CONUS

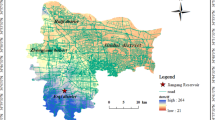

Our exploration of the precipitation records confirmed evidence36,37,38 of decadal variability in precipitation extremes over the CONUS. The most recent trends for increases in precipitation extremes were often noted post-1975. Consequently, we used an instrumental data set, the 1979-2021 CPC-CONUS land precipitation to confirm the trends noted in the reanalysis data. The recent linear trends in the 10- and 100-year return period events of daily annual maximum rainfall (A) and the preceding 5- and 30-days of rainfall (K5 and K30) across the CONUS for the CPC-CONUS data are shown in Fig. 3. We note that while there are isolated regions with statistically significant trends in A, K5 and K30 (Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 4a–f), there are widespread statistically significant trends in the joint events of 100-year A and 10-year K for both k = 5 and 30 days. Notably, substantial clusters of dams, specifically those with large size (height > 12.2 m or storage capacity > 1.23 million m3) and categorized as posing a high or significant hazard upon failure, are located in areas demonstrating increased occurrences of these joint events (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Fig. 4g, h). This is concerning since a) it suggests that these joint events are getting stronger/more frequent and b) even accounting for these trends, the joint (A*, K5*) or (A*, K30*) associated with the dam failure event often had very high return periods for many of the US dams that had a hydrologic failure in the last 22 years.

Recent linear trends in (a) 10-year annual maximum daily rainfall, (b) 100-year annual maximum daily rainfall, (c) 10-year 5-day precedent rainfall total, (d) 100-year 5-day precedent rainfall total, (e) 10-year 30-day annual maximum rainfall, and (f) 100-year 30-day annual maximum rainfall, for the 1979-2021 CPC-CONUS daily rainfall dataset. The color represents the ratio of the return level in 2021 to that in 1979.

Spatial distribution of aging dams and recent linear trends in (a) joint event of 100-year annual maximum daily and 10-year previous 5-day rainfall, and (b) joint event of 100-year annual maximum daily and 10-year previous 30-day rainfall, for the 1979-2021 CPC-CONUS daily rainfall dataset. The color represents the ratio of the return level in 2021 to that in 1979. Only large-sized dams, with height > 12.2 m (40 ft) or storage capacity > 1.23 million m3 (1000 acre-ft), categorized as high or significant hazard dams are displayed.

Discussion

There is a large literature that highlights the potential for higher and more frequent precipitation extremes and the associated potential for increased flooding as climate changes27,39. Much of this work focuses on daily and sub-daily precipitation. However, flooding requires a consideration of the antecedent conditions prior to a large rainfall event, i.e., the prior history of rainfall. The finding in this paper that most of the recent hydrologic dam failures are related to the joint 1-day and preceding rainfall event is consequently not a surprise. Although dams are ostensibly engineered to withstand inflow design floods under conservative hydroclimate conditions, however, our findings reveal that many recent failures have occurred under climate conditions significantly more moderate than those anticipated by the existing design criteria. This highlights that the traditional design criteria need to be revisited to consider a broader set of conditions that may actually lead to failure.

The fact that the frequency and severity of these compound events is increasing across the CONUS, and possibly in other places, adds an element of urgency to better understanding and predicting these conditions. Prior research emphasizes the role of persistent atmospheric circulation conditions and hemispheric scale quasi-periodic inter-annual and decadal climate variations as carriers of the information associated with such events16,17,18,19. However, given the predominant focus on climate change projections, research on the predictability of such mechanisms has been relatively limited.

The risk factor that is more difficult to map is the likely storage in the reservoir when a moderate or large rainfall event that could lead to overtopping may occur. This depends on the reservoir operator’s management strategy. Some relevant work in this direction exists40,41, but it typically requires data on reservoir inflows, outflows, and storage, which is not readily available at the continental scale. Moreover, an examination of the 2023 NID data6 reveals that for dams that are taller than 50 ft, and are rated as a significant hazard on failure, the condition of over 53% is unrated or unknown. When this is extended to include dams that have a high or significant hazard rating, the percentage of unrated or unknown condition increases to 74%. Consequently, it is difficult to assess the condition of dams that have previously failed and attribute the overtopping failure to additional factors.

A portfolio risk analysis of all US or global dams that considers the climate, fragility, and operational risk factors with a mapping to potential impacts from dam failure is needed to better understand the collective risk of cascading failure of critical infrastructure that would be triggered by dam failure and its socio-economic impacts5.

Methods

Dam incidents

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Dam Incident Database compiles a list of dam incidents that occurred within the US7. Spanning from 1874 to the present day, these records primarily originate from state programs and contain information such as the dam’s name, location, downstream hazard potential, incident date, and incident driver. Although this database may not include every dam incident that happened since 1874, it is the most extensive databases of dam incidents for the US, as ASDSO is the primary partner of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in the National Dam Safety Program (NDSP) and serves as the official voice for state dam safety.

For this study, we specifically focus on incidents attributable to hydrological factors or flooding since the year 2000, resulting in a selection of 552 dam incidents documented until 2021. The spatial distribution and the season of their occurrence are illustrated in Supplemental Fig. 2b. Some of these dam incidents have happened simultaneously, possibly within the duration of a single meteorological event. Consequently, although there were 552 incidents in total, they transpired over only 128 distinct days. A Mann-Kendall test shows a statistically significant upward trend in the annual number of dam incidents (Sen’s slope = 1.57, p-value = 0.001), as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1a.

We reiterate that the selection of dam incidents excludes those where snowmelt water was reportedly a triggering factor. Although snow accumulation and melting frequently lead to floods and dam failures, especially during the winter and spring seasons, limited access to long-term snow data hampers a complete evaluation of their severity (i.e., return period) and their role in dam incidents.

Precipitation data

We use data sourced from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Inter-comparison Project – Phase 3 (ISIMIP3), which is an initiative to provide consistent, bias-corrected climate datasets for impact modeling42,43. The project offers historical simulations forced by observational climate and socioeconomic information (ISIMP3a) and bias-corrected CMIP6 climate forcing for pre-industrial, historical, and different future emission scenarios (ISIMP3b), employing various General Circulation Models (GCMs). Data from the previous phase, ISIMIP2, has already been widely used in several studies related to climate and water resources44.

The ISIMP3a database provides four observational climate datasets; GSWP3-W5E5, 20CRv3-W5E5, 20CRv3-ERA5, and 20CRv3. All of them have daily temporal and 0.5° spatial resolutions. Their temporal coverage varies, and we used the 20CRv3-ERA5 dataset, which covers a period from 1901 to 2021. The 20CRv3-ERA5 dataset is generated based on the latest version of the European Reanalysis45 (ERA5) and ensemble member 1 of the Twentieth Century Reanalysis version 346 (20CRv3) interpolated to 0.5 degreed spatial resolution. The dataset combines ERA5 dataset for the period of 1979 – 2019 with 20CRv3 bias-adjusted towards ERA5 for the period of 1901 – 1978. The bias adjustment is done using ISIMIP3BASD v2.5.147 in order to reduce discontinuities at the 1978/1979 transition. Compared to other bias-adjustment and statistical downscaling methods, the ISIMIP3BASD v2.5.1 is shown to provide a more robust bias adjustment of extreme values and preserve trends more accurately across quantiles47,48. We used the average daily precipitation from the four nearest grid points surrounding a dam’s location, incorporating weighted values based on the proximity of these grid points to the dam.

In addition to the reanalysis precipitation data set, we also used the instrumental gridded daily precipitation data set, the Climate Prediction Center’s (CPC) Unified Gauge-Based Analysis of Daily Precipitation over CONUS (CPC-CONUS) from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)49. The CPC-CONUS is generated by interpolating gauge reports from multiple information sources available at CPC, including the Global Telecommunication System (GTS), Cooperative Observer Network (COOP), and other national and international meteorological agencies. It was shown in an earlier study that the optimal interpolation objective analysis technique, which is used to create the CPC dataset, is capable of generating daily precipitation analysis with biases of less than 1% over most parts of the global and land areas50. The quality of the dataset is assured by performing the quality control on the collected gauge reports by comparing them to the historical records and independent information from measurements at nearby stations, concurrent radar/satellite observations, as well as numerical model forecasts, especially focusing on zero and extreme values51.

Calculation of Return periods of A* and K*

We consider two types of precipitation statistics derived from each dam incident or rainfall grid cell i: the maximum 1-day precipitation within k days prior to the incident (A*) and the cumulative k-day precipitation total preceding the incident (K*), as serving a proxy for the antecedent wetness. While a more thorough analysis might utilize direct soil moisture product instead of using a proxy, such data were not universally available for a long time across all the 552 dam failure sites; hence, precipitation data were employed. Prior studies have shown the efficacy of recent precipitation as a surrogate for soil moisture levels52.

Return periods for A* and K* are determined based on the annual maximum daily precipitation (A) and total precipitation over k days preceding the date of A (K), respectively. This involves modeling the probability distributions of A and K and subsequently establishing the return periods for A* and K*. In addition, the return periods for the joint occurrence of A* and K* are determined using bivariate copulas. The return periods for A*, K*, and their joint occurrence are determined using a non-stationary model evaluated at the year of the dam incident and the year of dam construction completion. Preliminary analyses tested various values for k (e.g., 5, 10, and 30 days) to account for differing concentration times in watersheds upstream of the dams. However, the results for k = 10 days were very similar to those obtained for k = 5 days. Consequently, we present findings exclusively for k = 5 and 30 days only, offering a focused exploration of these time frames. We established an upper limit of 30 days for k, as the residence time of precipitation absorbed by the soil layer typically does not exceed this period53.

The Generalized Extreme Value (GEV) distribution is the limiting distribution of the maxima of independent and identically distributed random (i.i.d.) variables54. It is a popular choice for analyzing block maxima of hydrometeorological data. We use the GEV distribution to model the annual maximum daily precipitation (A). For each dam site \(i\), let \({A}_{i,t}\) denote the annual maximum daily precipitation for year t derived from the average daily precipitation series obtained from the four nearest grid points in proximity to the dam’s location. The probability distribution for \({A}_{i,t}\) is specified as:

where \({\mu }_{{A}_{i,t}}\), \({\sigma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\), and \({\gamma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\) are the location, scale, and shape parameters of the GEV distribution, respectively. The cumulative distribution function of \({A}_{i}\) evaluated at \({A}_{i,t}\) is given by:

Following Katz (2013)55, the non-stationarity of \({A}_{i,t}\) is modeled through linear trends in the parameters \({\mu }_{{A}_{i,t}},{\sigma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\) while treating \({\gamma }_{{A}_{i}}\) as time invariant:

We test the GEV distributions under four different assumptions to identify the best fit for the observed \({A}_{i,t}\) at each site: 1) No temporal trend, 2) Linear trend in \({\mu }_{{A}_{i,t}}\) only, 3) Linear trend in \({\sigma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\) only, and 4) Linear trend in both \({\mu }_{{A}_{i,t}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\). The model that yields the lowest Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) is selected for each site. We use the ‘ismev’ package56 in R to estimate the parameters of the univariate GEV distribution, employing the Maximum Likelihood estimators detailed in Coles (2001)54.

The k-day antecedent precipitation (K) is modeled using the 2-parameter gamma distribution (G2). The G2 distribution is considered a reasonable choice for daily or weekly precipitation events57,58. Let \({K}_{i,t}\) denote the total precipitation over k days preceding the date of the annual maximum precipitation in year t at the dam location of incident \(i\). Reparametrizing \({1/{\sigma }_{{K}_{i,t}}}^{2}\) and \({{\sigma }_{{K}_{i,t}}}^{2}{\mu }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) into \({\alpha }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) and \({\beta }_{{K}_{i,t}}\), as proposed by Johnson et al.59, allows \({K}_{i,t}\) to be modeled as:

where \({\alpha }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) and \({\beta }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) indicate the shape and scale parameters of the G2 distribution, respectively. The cumulative distribution function of G2 for \({K}_{i,t}\) is given by:

where \(\Gamma\) is the gamma function and \(\gamma\) is the lower incomplete gamma function. We model the non-stationarity of \({K}_{i,t}\) through the parameters \({\mu }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) by assuming they may change linearly over time:

Similar to the process for \({A}_{i,t}\), the best G2 distribution for each site is identified by assessing four different assumptions of linear trends in \({\mu }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) and \({\sigma }_{{K}_{i,t}}\) based on BIC. The ‘gamlss’ package60 in R was used to infer the parameters of the univariate G2 distribution. The estimated values of the distribution parameters (\({\mu }_{{A}_{i,t}}\), \({\sigma }_{{A}_{i,t}}\), \({\mu }_{{K}_{i,t}}\), and \({\sigma }_{{K}_{i,t}}\)) and their trends are shown in Supplemental Figures 5 and 6, respectively.

For each dam incident \(i\), the determination of the return periods for \({A}_{i}^{* }\) (\({T}_{{A}_{i}^{* }})\) and \({K}_{i}^{* }\) (\({T}_{{K}_{i}^{* }})\) at year t is based on the probability distributions modeled for \({A}_{i}\) and \({K}_{i}\):

The probability distributions of \({A}_{i}\) and \({K}_{i}\) serve as the null distributions for \({A}_{i}^{* }\) and \({K}_{i}^{* }\).

Calculation of return period of the joint occurrence of A* and K*

The determination of the return period for the simultaneous occurrence of A* and K* relies on establishing the joint probability distribution of A and K. In this study, the dependence structure between A and K is modeled using copulas, which have been used extensively to specify multivariate distributions for statistical modeling of data. Prior to modeling their joint distributions, an assessment was conducted to ascertain whether the dependence between A and K changes over time.

To investigate whether the dependence between \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\) changes over time, we test the temporal variation in the correlation \({\rho }_{i,t}\) between \({F}_{{A}_{i}}\left({A}_{i,t}\right)\) and \({F}_{{K}_{i}}\left({K}_{i,t}\right).\) For simplicity, we denote \({F}_{{A}_{i}}({A}_{i,t})\) as \({u}_{i,t}\) and \({F}_{{K}_{i}}({K}_{i,t})\) as \({v}_{i,t}\), hereafter. Note that by Eqs. (2) and (5), the temporal trends in the mean and variance of \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\) are effectively addressed in the construction of \({u}_{i,t}\) and \({v}_{i,t}\), and thus we expect the mean and variance of \({u}_{i,t}\) and \({v}_{i,t}\) are constant over time. Then an estimate of \({\rho }_{i}\) would be provided by:

where \({m}_{{u}_{i}}\), \({m}_{{v}_{i}}\), \({s}_{{u}_{i}}\), and \({s}_{{v}_{i}}\) are the mean and standard deviation of \({u}_{i,{t}}\) and \({v}_{i,t}\), respectively. If the dependence between \({u}_{i,t}\) and \({v}_{i,t}\) is stationary, then the expected value of the cross product \({r}_{i,t}={u}_{i,t}{v}_{i,t}\) should be invariant with time. We explore the stationarity of \({r}_{i,t}\) using the Mann-Kendall test, to assess whether modeling the non-stationarity in the dependence structure is necessary. This analysis revealed no significant trends in dependence between \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\) at the selected dams, implying a stationary dependence structure suffices for bivariate models of \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\).

The multivariate cumulative distribution function of \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\) is then represented in terms of their marginal of \({u}_{i,t}\) and \({v}_{i,t}\), with a stationary copula function \({C}_{i}\), defined by a copula parameter \(\theta\):

There are several parametric copula families available, and the strength of bivariate dependence is usually controlled by \(\theta\). Using the ‘VineCopula’ package61 in R, we determine the optimal set of copula family and \(\theta\) that best fits the given bivariate distribution based on the BIC statistics for each site \(i\).

As we accommodate non-stationarity for both \({A}_{i,t}\) and \({K}_{i,t}\), the probability of their joint exceedances for a fixed set of thresholds, such as \({A}_{i}^{* }\) and \({K}_{i}^{* }\), may also vary with time. Here, we measure the probability of joint exceedances for \({A}_{i}^{* }\) and \({K}_{i}^{* }\) at time t, i.e., \(p\left({A}_{i,t}\, > \,{A}_{i}^{* },\,{K}_{i,t} \,> \,{K}_{i}^{* }\right)\), using copulas62:

Then the return period of the joint occurrence of \({A}_{i}^{* }\) and \({K}_{i}^{* }\) at year t, \({T}_{{A}_{i}^{* },{K}_{i}^{* }}(t)\), is calculated as:

Uncertainty of the estimated return periods for \({A}_{i}^{* }\), \({K}_{i}^{* }\), and their joint exceedance are shown in Supplemental Fig. 7.

Data availability

The Association of State Dam Safety Officials (ASDSO) Dam Incident Database may be obtained from their website at <https://damsafety.org/incidents>. The reanalysis precipitation dataset (20CRv3-ERA5) from the Inter-Sectoral Impact Model Inter-comparison Project – Phase 3 (ISIMIP3) may be obtained from the project website at <https://www.isimip.org/gettingstarted/input-data-bias-adjustment/details/105/>. The Climate Prediction Center’s (CPC) Global Unified Gauge-Based Analysis of Daily Precipitation (CPC-CONUS) dataset may be obtained from Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store at <https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/insitu-gridded-observations-global-and-regional?tab=overview>.

References

National Performance of Dams Program. Dam failures in the U.S., NPDP-01 V1. https://npdp.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/reports/npdp_dam_failure_summary_compilation_v1_2018.pdf (2018).

Ho, M. et al. The future role of dams in the United States of America. Water Resources Res. 53, 982–998 (2017).

Concha Larrauri, P. & Lall, U. Assessing the exposure of critical infrastructure and other assets to the climate induced failure of aging dams in the US. Final Report for the Global Risk Institute (2020).

Hariri-Ardebili, M. A. & Lall, U. Superposed natural hazards and pandemics: breaking dams, floods, and COVID-19. Sustainability 13, 8713 (2021).

Concha Larrauri, P., Lall, U. & Hariri-Ardebili, M. A. Needs for portfolio risk assessment of aging dams in the United States. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manag. 149, 04022083 (2023).

U.S Army Corps of Engineers. National Inventory of Dams. https://nid.sec.usace.army.mil/%23/ (2023).

Association of State Dam Safety Officials. Dam Incident Database Search. https://www.damsafety.org/incidents (2023)

Achterberg, D. et al. Federal Guidelines for Dam Safety: Selecting and Accommodating Inflow Design Floods for Dams, Interagency Committee on Dam Safety (Federal Emergency Management Agency, 2014).

Mishra, A. et al. An overview of flood concepts, challenges, and future directions. J. Hydrol. Eng. 27, 03122001 (2022).

Fernandes, W., Naghettini, M. & Loschi, R. A Bayesian approach for estimating extreme flood probabilities with upper-bounded distribution functions. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 24, 1127–1143 (2010).

Nathan, R. et al. Estimating the exceedance probability of extreme rainfalls up to the probable maximum precipitation. J. Hydrol. 543, 706–720 (2016).

Vahedifard, F., AghaKouchak, A., Ragno, E., Shahrokhabadi, S. & Mallakpour, I. Lessons from the Oroville dam. Science 355, 1139–1140 (2017).

Landers, J. Michigan dam failures were ‘foreseeable and preventable,’report finds. Civil Eng. 92, 12 (2022).

Samuels, P. Flood risks from failure of infrastructure. J. Flood Risk Manag. 16, e12960 (2023).

Hossain, F. et al. Climate feedback–based provisions for dam design, operations, and water management in the 21st century. J. Hydrol. Eng. 17, 837–850 (2012).

Ropelewski, C. F. & Halpert, M. S. North American precipitation and temperature patterns associated with the El Niño/Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Monthly Weather Rev. 114, 2352–2362 (1986).

Kossin, J. P., Camargo, S. J. & Sitkowski, M. Climate modulation of North Atlantic hurricane tracks. J. Clim. 23, 3057–3076 (2010).

Steinschneider, S. & Lall, U. Spatiotemporal structure of precipitation related to tropical moisture exports over the eastern United States and its relation to climate teleconnections. J. Hydrometeorol. 17, 897–913 (2016).

Schreck, C. J. III Global survey of the MJO and extreme precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094691 (2021).

Chen, X. & Hossain, F. Understanding future safety of dams in a changing climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 100, 1395–1404 (2019).

Wright, D. B., Bosma, C. D. & Lopez‐Cantu, T. US hydrologic design standards insufficient due to large increases in frequency of rainfall extremes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 8144–8153 (2019).

Najibi, N., Devineni, N. & Lu, M. Hydroclimate drivers and atmospheric teleconnections of long duration floods: An application to large reservoirs in the Missouri River Basin. Adv. Water Resour. 100, 153–167 (2017).

Mallakpour, I., AghaKouchak, A. & Sadegh, M. Climate‐induced changes in the risk of hydrological failure of major dams in California. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 2130–2139 (2019).

Trenberth, K. E. Changes in precipitation with climate change. Clim. Res. 47, 123–138 (2011).

Villarini, G. et al. On the frequency of heavy rainfall for the Midwest of the United States. J. Hydrol. 400, 103–120 (2011).

Kunkel, K. E. et al. Monitoring and understanding trends in extreme storms: State of knowledge. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 499–514 (2013).

Rahmani, V. & Harrington, J. Jr Assessment of climate change for extreme precipitation indices: a case study from the central United States. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 1013–1025 (2019).

Papalexiou, S. M. & Montanari, A. Global and regional increase of precipitation extremes under global warming. Water Resour. Res. 55, 4901–4914 (2019).

Nakamura, J., Lall, U., Kushnir, Y., Robertson, A. W. & Seager, R. Dynamical structure of extreme floods in the US Midwest and the United Kingdom. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 485–504 (2013).

Lu, M., Lall, U., Schwartz, A. & Kwon, H. Precipitation predictability associated with tropical moisture exports and circulation patterns for a major flood in France in 1995. Water Resour. Res. 49, 6381–6392 (2013).

Sasanakul, I. et al. Dam failures from a 1000-year rainfall event in South Carolina. Geotech. Front. 2017, 244–254 (2017).

New Jersey Water Science Center. (2011, October 20). New Jersey Experienced Record Flooding At 7 USGS Gages During August 14-16. U.S. Geological Survey. https://www.usgs.gov/news/flood-august-14-16-2011 (2011).

Lumia, R., Firda, G. D. & Smith, T. L. Floods of 2011 in New York. US Department of the Interior, US Geological Survey (2014).

Jain, S. & Lall, U. Floods in a changing climate: Does the past represent the future? Water Resour. Res. 37, 3193–3205 (2001).

Zeder, J. & Fischer, E. M. Decadal to centennial extreme precipitation disaster gaps–long-term variability and implications for extreme value modelling. Weather Clim. Extremes 43, 100636 (2023).

Yu, L., Zhong, S., Pei, L., Bian, X. & Heilman, W. E. Contribution of large-scale circulation anomalies to changes in extreme precipitation frequency in the United States. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 044003 (2016).

Carvalho, L. M. Assessing precipitation trends in the Americas with historical data: a review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 11, e627 (2020).

Amonkar, Y., Doss-Gollin, J. & Lall, U. Compound climate risk: diagnosing clustered regional flooding at inter-annual and longer time scales. Hydrology 10, 67 (2023).

Visser, J. B., Wasko, C., Sharma, A. & Nathan, R. Changing storm temporal patterns with increasing temperatures across Australia. J. Clim. 36, 6247–6259 (2023).

Zhao, Q. & Cai, X. Deriving representative reservoir operation rules using a hidden Markov-decision tree model. Adv. Water Resour. 146, 103753 (2020).

Turner, S. W., Steyaert, J. C., Condon, L. & Voisin, N. Water storage and release policies for all large reservoirs of conterminous United States. J. Hydrol. 603, 126843 (2021).

Warszawski, L. et al. The inter-sectoral impact model intercomparison project (ISI–MIP): project framework. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3228–3232 (2014).

Rosenzweig, C. et al. Assessing inter-sectoral climate change risks: the role of ISIMIP. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 010301 (2017).

Sauer, I. J. et al. Climate signals in river flood damages emerge under sound regional disaggregation. Nat. Commun. 12, 2128 (2021).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Slivinski, L. C. et al. Towards a more reliable historical reanalysis: Improvements for version 3 of the Twentieth Century Reanalysis system. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 145, 2876–2908 (2019).

Lange, S. Trend-preserving bias adjustment and statistical downscaling with ISIMIP3BASD (v1. 0). Geoscientific Model Dev. 12, 3055–3070 (2019).

Mengel, M., Treu, S., Lange, S. & Frieler, K. ATTRICI v1. 1–counterfactual climate for impact attribution. Geoscientific Model Dev. 14, 5269–5284 (2021).

Copernicus Climate Change Service, Climate Data Store.Temperature and precipitation gridded data for global and regional domains derived from in-situ and satellite observations. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS). https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.11dedf0c (Accessed on 01-Mar-2023) (2021).

Chen, M. et al. Assessing objective techniques for gauge-based analyses of global daily precipitation. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 113, D04110 (2008).

Chen, M. & Xie, P. (2008). Quality Control of Daily Precipitation Reports at NOAA/CPC, Paper presented at AMS 12th conferences on IOAS-AOLS, 20-24 January New Orleans, LA.

Yuan, S., Quiring, S. M. & Zhao, C. Evaluating the utility of drought indices as soil moisture proxies for drought monitoring and land–atmosphere interactions. J. Hydrometeorol. 21, 2157–2175 (2020).

McColl, K. A. et al. Global characterization of surface soil moisture drydowns. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 3682–3690 (2017).

Coles, S. Classical extreme value theory and models. In An introduction to statistical modeling of extreme values. p. 45-73. (Springer, 2001).

Katz, R. W. Statistical methods for nonstationary extremes. In Extremes in a changing climate. p. 15-37. (Springer, 2013).

Heffernan, J. E., Stephenson, A. G. & Gilleland, E. ismev: an introduction to statistical modeling of extreme values. R package version 1.42. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ismev (2018).

Buishand, T. A. Some remarks on the use of daily rainfall models. J. Hydrol. 36, 295–308 (1978).

Geng, S., de Vries, F. W. P. & Supit, I. A simple method for generating daily rainfall data. Agric. For. Meteorol. 36, 363–376 (1986).

Johnson, N. L., Kotz, S. & Balakrishnan, N. Continuous Univariate Distributions, Vol. 2, p. 289. (John wiley & sons, 1995).

Rigby, R. A. & Stasinopoulos, D. M. Generalized additive models for location, scale and shape. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C: Appl. Stat. 54, 507–554 (2005).

Nagler, T. et al. VineCopula: Statistical Inference of Vine Copulas. R package version 2.4.4. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=VineCopula (2022).

Tilloy, A., Malamud, B. D., Winter, H. & Joly-Laugel, A. Evaluating the efficacy of bivariate extreme modelling approaches for multi-hazard scenarios. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 2091–2117 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This research is based upon work supported in part by the Institute for Geospatial Understanding through an Integrative Discovery Environment (I-GUIDE) that is funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under award No. 2118329. Partial support was also provided by the NSF within the framework of America’s Water Risk: Water System Data Pooling for Climate Vulnerability Assessment and Warning System, award No. 2040613. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of NSF.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors actively participated in discussions and made significant contributions to the completion of this paper. J.H. contributed to the conceptualization, implemented the statistical models, and, in collaboration with U.L., analyzed the results. U.L. also contributed to the conceptualization and developed the methodology. J.H. prepared visualizations and drafted the manuscript. After several rounds of revision by both J.H. and U.L., the final version of the manuscript was approved by both authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hwang, J., Lall, U. Increasing dam failure risk in the USA due to compound rainfall clusters as climate changes. npj Nat. Hazards 1, 27 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-024-00027-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-024-00027-6

This article is cited by

-

Dynamic and thermodynamic drivers of extreme precipitation under nonstationarity: implications for probable maximum precipitation across North America

Natural Hazards (2026)

-

Detailed inventory and initial analysis of landslides triggered by extreme rainfall in the northern Huaiji County, Guangdong Province, China, from June 6 to 9, 2020

Geoenvironmental Disasters (2025)

-

Assessing climate change impacts on flood risk in the Yeongsan River Basin, South Korea

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

Historical changes in overtopping probability of dams in the United States

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Catastrophic “hyperclustering” and recurrent losses: diagnosing U.S. flood insurance insolvency triggers

npj Natural Hazards (2025)