Abstract

Pumice drifting poses substantial risks to maritime navigation and coastal communities. While traditional ocean-current-based simulations effectively predict drifting patterns, they are resource-intensive and unsuitable for real-time use following abrupt eruptions. This study proposes a data-driven framework that enables rapid, low-cost pumice drift prediction, leveraging daily-reported Kuroshio Current axis (KCA) patterns and conducting similarity searches on pre-existing simulation datasets. Focusing on eruptions at Bayonnaise Rocks in the Izu Islands, Japan, we demonstrate that the dynamic time warping distance, a measure of similarity between the current KCA pattern and historical KCA patterns, accurately predicts drifting scenarios within the critical first 10 days post-eruption. This method reliably identifies high-risk cases, including those affecting coastal regions, without requiring new simulations. By refining simulation datasets and enhancing prediction accuracy, this framework can become a practical tool for hazard assessments, offering a scalable solution for proactive disaster-risk management in response to unpredictable pumice eruptions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pumice drift can cause unexpected and substantial damage to maritime transportation, fisheries, tourism, and important coastal infrastructures1,2. For instance, pumice ejected from the Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba eruption in August 2021 drifted on the Kuroshio countercurrent and reached the Okinawa Islands ~2 months later, causing unexpected damage and social problems3,4,5. Numerous past events of pumice drift have been recorded around the Izu-Bonin Islands6. Over the past couple of years, several eruptions accompanied by pumice ejection and drifting phenomena have been observed, prompting marine warnings by governmental agencies7.

As of December 2024, authorities are issuing eruption and marine warnings at Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho) and Sumisujima Island of the Izu Islands, urging caution around floating debris such as pumice8. This region, being considerably closer to mainland Honshu than Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba, admits a large volume of active maritime traffic. The pumice from large-scale ejections can reach the coastal areas of the Tokyo metropolitan region within days to weeks, causing widespread damage. To mitigate these potential impacts, the pumice drift distribution must be rapidly predicted, ideally in real time.

Previous studies showed that Lagrangian particle tracking simulations using ocean current data9,10 effectively predicted pumice drift distributions1,2,11,12. Many drift simulation studies have been performed since the 2021 Fukutoku-Okanoba pumice drift event13,14,15. Since November 2021, when pumice reached Okinawa Island 2 or 3 months after the eruption, simulation results have been updated daily, aiding local stakeholders in decision making and countermeasures16.

However, physical simulations require large human and computational resources and must be configured in advance. This process encompasses not only computation but also more general tasks, such as data preparation, parameter configuration, output processing, and expert mobilization, all of which demand skilled specialists. Maintaining a system that continuously and quickly conducts such resource-intensive simulations is often impractical. In addition, the timing and scale of volcanic eruptions are unpredictable and many eruptions are relatively small. Therefore, the merits of dedicating substantial research resources to every submarine eruption are questionable. In regions such as the Izu Islands, where maritime traffic is heavy, because the islands are only few hundred kilometers away from mainland Honshu, pumice can reach the coast within days; therefore, developing a simple and accessible method that provides real-time and proactive predictions without the need for resource-intensive simulations is crucial.

In this study, we develop a system that can automatically and accurately predict the drift distribution of pumice in real-time if a pumice eruption occurs today. Instead of conventional physical simulations, we propose a data-driven, analog-based prediction system that utilizes existing simulation results. Specifically, we replace physical prediction simulations with previous drift simulation results obtained by our previous study17. Our system identifies pre-existing drift simulations corresponding to ocean current patterns similar to the present ocean current pattern. To identify similar ocean current patterns, we adopt the path of the Kuroshio current axis (KCA), representing the fastest flow path of the Kuroshio current, as the similarity criterion. The Kuroshio, which flows from west to east along the southern coast of Honshu, is the most important element characterizing ocean currents near Japan.

Our platform searches for similar patterns within the dataset of KCA patterns and outputs the corresponding simulation data of the searched results. This type of search, called a similarity search18, is commonly used in the data engineering field and has been actively studied19,20. A similarity search must accurately assess the similarity between a new data point and the existing data. Whereas many similarity searches use traditional metrics such as the Euclidean distance, we require a more appropriate path-comparing measure for the KCA, a single datum. We perform a similarity search using four representative distance metrics for path data—the Hausdorff distance21, Fréchet distance22, average DTW distance23, and Wasserstein (WS) distance24—to compare their performance and identify the most suitable metric for KCA-based drift prediction.

Distance metrics have been widely used in time-series prediction across various fields25,26,27,28,29, including finance, meteorology, and oceanography. These studies demonstrate that distance-based similarity searches effectively capture temporal patterns and predict future trends. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to apply distance-based similarity search to the KCA for pumice drift prediction. This novel approach enables the rapid, data-driven forecasting of pumice drifting patterns without relying on computationally expensive physical simulations, making it a valuable tool for proactive hazard assessments.

Through validation experiments, we demonstrate that drift distributions can be roughly predicted from daily observation-based KCA position data, confirming the effectiveness of the system. The system provides preliminary drift predictions rapidly without running resource-intensive physical simulations, thereby supporting decision making and offering sufficient time to prepare and execute detailed physical drift simulations when necessary.

In the following sections, we first overview the alternative prediction system, introduce the target volcanic regions of likely pumice eruptions, and explain the KCA data used in similarity evaluations of ocean current patterns. We then describe the criteria of the similarity evaluation between present and past ocean current patterns and overview the drift simulations underlying the prediction system. Next, we validate the effectiveness of the system by comparing the drift distribution predicted by the system with the assumed true drift simulation results. We also consider the most effective distance metric and most appropriate number of outputted scenarios based on the validation results. At the end of the results section, we simulate an expected pumice eruption at Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho) in the southern Izu Islands, where an eruption warning has been enacted since September 20248. In the discussion section, we demonstrate the advantage of the proposed method and highlight the challenges and improvements necessary for more accurate predictions. Finally, we discuss the practical use of the system for potential pumice eruptions.

Results

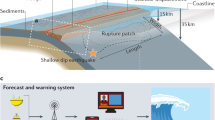

Prediction system

Figure 1 presents an overview of the proposed method. Inputted with the current KCA, the method searches for periods with similar patterns from a dataset of the past KCA locations and outputs the drift simulation result data (scenarios)17. This data-driven estimation of the future drift distribution removes the need for conducting a new physical drift simulation whenever a pumice eruption occurs. The following subsections describe the target area, datasets, and methods of the present study.

The term “query KCA” represents the Kuroshio Current axis (KCA) on the specified day, while the “reference KCAs” correspond to historical KCA paths obtained from the simulation dataset. The method identifies historical KCA paths most similar to the query KCA using a similarity metric (e.g., dynamic time warping (DTW) distance) and outputs the corresponding drift patterns utilizing existing simulations. These predictions serve as analogs for the anticipated pumice drifting behavior.

Target volcano: Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho)

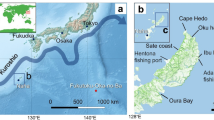

We assume that a large amount of pumice is ejected from Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho) in the southern part of the Izu Islands (Fig. 2). Bayonnaise Rocks occupies the Myojinsho Caldera, one of the most active volcanic eruption regions in the Izu–Ogasawara Islands. In fact, the Myojinsho Caldera has been designated as an active volcano by the Japan Meteorological Agency30,31.

Among numerous eruptions recorded over the past 100 years, the 1953 eruption was followed by a large amount of pumice drift and a research vessel with 31 crew members was lost. In addition, eruption and marine warnings were issued when discolored water was observed in January 2023. These warnings remain in place as of December 202430,31.

As shown in Fig. 2, the main Kuroshio current frequently passes near Bayonnaise Rocks. The Kuroshio current and its representative surrounding ocean currents strongly influence the drift distribution pattern of pumice ejected from this area3,17. Therefore, the Bayonnaise Rocks volcano is considered as an ideal candidate for evaluating the proposed method.

Input: Kuroshio Current Axis dataset

The KCA, representing the fastest flow path of the Kuroshio, is comprehensively determined from the observed data of ocean current velocity, water temperature, and sea surface height32. The KCA data are published in the Marine Information Bulletin of the Japan Coast Guard and are essential for understanding the ocean current patterns near Japan. These data are widely used by fishermen, ferry operators, and shipping companies to guide their operations. Since 2007, KCA data have been published almost daily, except on weekends, public holidays, and year-end and New Year holidays. Before 2007, the publication frequency was notably lower, with updates provided bimonthly prior to 2000 and weekly until 200532.

The KCA varies as shown in Fig. 2. Depending on the observation period and data accuracy, the two-dimensional point cloud data of the KCA contain dozens to over 100 latitude and longitude coordinates representing the positions through which the axis passes. Focusing on the southern coast of Honshu, the Kuroshio flows from the eastern coast of Kyushu, along the southern coast of Shikoku, and finally crosses the Izu Islands, advancing eastward along the eastern coast of Japan. As shown in Fig. 2, the current can flow linearly or windingly near the southern coast of the Kii Peninsula. The largely meandering path in 2020 is referred to as the “Kuroshio Large Meander.”

In the actual system, we constructed a custom dataset specifically for the similarity search performed in this study. From this dataset, we selected the KCA data demonstrating one-to-one correspondence with the output simulation data. For each simulation, we identified and included the KCA data that most closely aligned with the hypothetical eruption date. Specifically, we selected the KCA data whose observation period (from the start of observation to the publication date) included the corresponding hypothetical eruption date. Among overlapping periods, we chose the KCA data with the longest overlap, ensuring that the observation start date was as close as possible to the hypothetical eruption date. Because the simulation data17 comprise monthly datasets from 1982–2015, the constructed dataset includes 408 KCA data periods, each linked to a specific hypothetical eruption date.

Main processing: Similarity search

A similarity search for KCA requires a distance metric that quantitatively evaluates the similarity or proximity of shapes and the positional relationships between two paths. The actual system sorts the 408 periods in the custom dataset in the ascending order of their selected distance-metric scores and outputs the corresponding drifting simulation results of the top-ranked periods. The specific distance metric is selected through validation experiments, as will be described later.

The curve patterns were compared in terms of four representative distance metrics (see Methods and Fig. 3): the Hausdorff distance21, the Fréchet distance22, the average distance obtained from dynamic time warping (DTW) distances23, and the Wasserstein distance24.

a Hausdorff Distance: The distance from Curve B to Curve A (light blue dashed line) exceeds the distance from Curve A to Curve B (pink line). The longer distance is adopted as the Hausdorff distance. b Fréchet Distance (light green dashed line) and average dynamic time warping (DTW) distance. c Wasserstein Distance: Represents the correspondences between the point clusters (black dashed lines in (b, c)). d Distance-matrix Representation of DTW Distance: The color bar indicates the distance between points in Curve A to Curve B, d(ai, bj). Each point along the warping path (black line) corresponds to a point-to-point relationship in the DTW distance calculation. The pink and light blue circles correspond to the distances from Curve B to Curve A and from Curve A to Curve B, respectively, in panel (a). The light green squares correspond to the Fréchet distance.

Output: Drifting simulation dataset

The output section provides the drift simulation data corresponding to the top candidate periods identified in the main processing section. The drift simulation results include the tracking data of virtual pumice-particle groups ejected from Bayonnaise Rocks17 (See the Methods section for details). As explained in results of the validation experiments, the number of output results is adjusted to seven. This optimally balances the estimation error with the coverage ratio, which refers to the proportion of successful prediction with output results containing good scenarios with a small error.

Figure 4 shows an example of the drift simulation data. The output covers the 10 day post-eruption period. The duration setting is determined by (1) the difficulty in making precise analog-based predictions over periods longer than few weeks and (2) the general lead time (ranging from approximately several days to one business week) of setting up a system for physical numerical simulations of the drift, including the broad workflow of data preparation, parameter setup, computation, data processing, and expert allocation, after a large-scale eruption necessitating highly accurate prediction. This period is also crucial for making initial decisions regarding hazard response and mitigation measures.

Validation experiments on existing datasets

Experimental framework

To verify the effectiveness of the system and select an appropriate distance metric for measuring the KCA similarity, we solve the known-answer problem during periods when both the KCA data and drift simulation data are available. The concept of validation experiments is shown in Fig. 5. Specifically, we first input the query KCA data from the periods having the “true” existing drift simulation results. The system then outputs existing drift simulation results as the predicted scenarios. Next, we compare the similarities between the predicted drift simulations and the “true” forward-calculated drift simulation results for each distance metric and select the distance metric yielding the highest similarity.

This evaluation uses the drift distribution patterns of 24 cases corresponding to monthly pumice ejections between 2014 and 2015 as the ground truth data. These data represent the most recent 2 years of available simulations17. The remaining 32 years of data from 1982 to 2013, comprising 384 months of drift simulation results, are used as the reference historical simulation data for prediction.

For each test case, similarities between the queried KCA and reference KCA dataset containing 384 months of data are calculated based on the Hausdorff distance, Fréchet distance, average DTW distance, and WS distance. Based on these similarity scores, multiple existing drift patterns are selected as potential scenarios for predicting pumice drift. The key evaluation criterion in this situation is whether the top-ranked patterns identified based on the KCA similarity truly tend to rank highly in terms of drift pattern accuracy, as measured by the evaluation metric Dpum (defined in the next subsection). This metric quantifies the similarity between the true drift pattern and predicted historical drift patterns. Through this validation, we determine the most effective distance metric and optimal number of output past patterns. Additionally, we visually inspect the estimated drift patterns to ensure that the selected scenarios capture key features of the true drift distribution.

The target volcano is Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho) and the predictions are short-term, spanning ~10 days post-eruption. Therefore, the ocean current patterns around the Izu Islands region are particularly important. The similarity of the KCA in regions far from this area is not critical and might degrade the similarity evaluation within the key region of interest. To avoid this problem, we compare only the portion of the KCA path between the first point crossing 135∘E longitude and the first point reaching 145∘E longitude as the current flows from west to east.

Evaluation metrics

In this test, the similarity between the true drift pattern and the predicted output past patterns is measured using the following distance metric, which considers each of the monitored virtual pumice particles:

where npum is the number of virtual pumice particles (here set to 500, the number of points for each day in the output figure (e.g. Fig. 4)), and nday represents the number of days over which the prediction results are outputted (here set to 10). \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i,t}^{{\rm{out}}}\) and \({{\boldsymbol{x}}}_{i,t}^{{\rm{true}}}\) represent the positions of virtual pumice particle i on day t in the output and true simulation, respectively. The function d(a, b) represents the distance between positions a and b. Like the KCA distance metrics, the actual distance is calculated from the latitude and longitude data using the Haversine formula.

In this validation experiment, we evaluate whether the top-k-ranked scenarios selected based on the KCA similarity also rank among the most accurate when assessed in terms of the drift pattern similarity. To quantify this, we assign each reference scenario a rank Rpum based on Dpum in the ascending order, where lower values indicate greater similarity to the true drift pattern. For each test case, we calculate the mean Rpum of the top-k selected scenarios, denoted as \({\bar{R}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\). To evaluate overall predictive performance, we compute the average of this mean rank across all 24 test cases.

Furthermore, in practical hazard assessments, ensuring that at least one of the selected scenarios closely matches the true drift pattern is necessary. To verify this, we introduce the coverage rate as an additional evaluation metric, which quantifies the proportion of test cases in which at least one of the top-k-selected scenarios ranks within the top 5% of all 384 historical scenarios based on Dpum. This metric serves as an indicator of the method’s ability to capture high-risk scenarios within the predicted outputs.

Experimental results

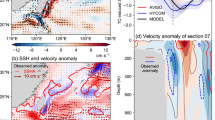

To overview the general behavior of the distance metrics and evaluation metric Dpum and their relationships among each other, we analyze the overall correlation structure. Figure 6 presents a scatter plot matrix showing the correlations between pairs of distance metrics for evaluating KCA similarity and between the distance metrics and the evaluation metric Dpum, which pertains to the prediction results of pumice drifting patterns. Each plot includes all similarity values between the reference dataset of 384 months and 24 test cases (9216 points in total), regardless of the similarity magnitude.

From the correlations between the KCA distance metrics, we observe a nearly 1:1 relationship between the Hausdorff and Fréchet distances, with slightly smaller values of the Fréchet distance. The average DTW distance is generally proportional to but smaller than these metrics, typically concentrated within one-third to two-thirds of the Hausdorff and Fréchet values. In contrast, the Wasserstein distance shows a more complex distribution with values that often exceed the average DTW distance. These relationships are consistent with the definitions and meanings of the distance metrics given in the methods section.

The scatter plots on the bottom row and rightmost column of Fig. 6 correlate the KCA distance metrics with the evaluation metric of pumice drifting patterns. These scatter plots show no clear correlations and the relationships are very weak, with Peason’s correlation coefficients, which measures the linear relationship between two variables, of 0.111, 0.112, 0.168, and 0.048 for the Hausdorff distance, Fréchet distance, average DTW distance, and WS distance, respectively.

Figure 7 displays the correlation between the rankings of the KCA similarity and that of Dpum, namely Rpum, for each of the four distance metrics; here, both rankings are arranged in the ascending order. Across the entire ranking range, the scatter plots exhibit weak correlation, and the Pearson’ correlation coefficients for each distance metric are 0.121, 0.124, 0.177, and 0.024 for the Hausdorff distance, Fréchet distance, average DTW distance, and WS distance, respectively.

However, a noticeable cluster of high-density data points appears in the lower-ranked regions, approximately spanning several to several tens of ranks. Further, kernel density estimation confirms a statistically significant concentration of points in these regions. Notably, the DTW-based metric exhibits a particularly dense and large cluster of data points in the top-ranked region (i.e., both higher KCA similarity and higher Dpum similarity) compared to the other metrics. These results suggest a general trend in which selecting past periods with high KCA similarity tends to output scenarios that more closely match the true drift pattern. In particular, large clustering observed for the DTW-based metric further supports its suitability for identifying relevant historical drift scenarios.

Whereas Figs. 6 and 7 illustrates the overall correlations across the entire reference dataset, actual predictions utilize only the top-ranked reference data with the highest similarity. Figure 8 shows variations in the Peason’s and Speaman’s correlation coefficients after isolating the top-ranked reference data with the smallest KCA distances. Spearman’s rank correlation methods assess the strength of monotonic relationships between variables. The rank k on the horizontal axis indicates the number of most similar references considered in each case and the vertical axis represents the average correlation coefficient across all 24 cases.

Notably, when only the top several dozen ranks are selected, both Peason’s and Spearman’s correlation coefficients range from ~0.4 to 0.7, suggesting a significant positive correlation. Note that the correlation coefficient does not directly reflect the prediction accuracy; therefore, Fig. 8 alone cannot provide detailed insights into the accuracy of the method. Nevertheless, the model selects periods with high similarity in the KCA patterns, yielding output drifting patterns that approach the true pumice distribution.

Figure 9 a plots the average values of the evaluation metric \({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) of deviations from the true drifting pattern as functions of rank k for each KCA distance measure. According to this figure, averaged \({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) decreases as more higher-ranked references (i.e., those with lower numerical ranks) are included, particularly those within the top 10 ranks, where the decrease is substantial across all distance metrics. Notably, statistical errors in \({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) increase as lower numerical ranks are included owing to the reduced sample size. Despite these errors, the results confirm that selecting periods with similar Kuroshio axis patterns enables reasonable predictions of pumice drifting patterns.

Figure 9b illustrates the average ranking of selected scenarios based on \({\bar{R}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\), rather than \({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\). The trends observed in these figures closely resemble those in Figure 9a, indicating that the ranking behavior remains consistent across different distance metrics. Notably, for the top-10 selected scenarios, the average \({\bar{R}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) ranges from ~120 to 150 across all distance metrics, except the WS distance. This is substantially lower than the random baseline rank of 192.5, confirming that selecting periods with a high KCA similarity yield scenarios that more closely match the true drift pattern.

Figure 10 shows the coverage rate, defined as the proportion of output results containing the top 5% closest reference scenarios with small Dpum in at least one sample. Here, the top-ranked reference data are based on the smallest KCA distance. The coverage rate represents the proportion of predicted scenarios that include at least one of the closest matches—scenarios with the smallest Dpum—with the real drifting patterns. In simple terms, it quantifies how often the system successfully identifies a scenario similar to the real drifting pattern within its top-ranked predictions. The coverage rate is an intuitive metric for evaluating the system’s reliability in identifying realistic pumice drifting scenarios. By focusing on whether at least one highly similar scenario appears among top predictions, the metric emphasizes practical relevance over precise error minimization. For ranks within the top 10, the average DTW distance exhibits a clearly higher coverage rate than the other distance metrics. It also achieves a smaller error than the other metrics (Fig. 8b).

From these figures, we determine the most effective distance metric and output number of the existing simulation results. The distance metric should minimize the average error and its results should approach the true solution even in cases of limited output. Increasing the number of outputs increases the average error (Fig. 8b), but excessively limiting the outputs increases the risk of excluding the results close to the true solution.

Based on these results, the average DTW distance was adopted as the distance metric for the KCA, unless otherwise noted. Given that the average DTW distance inherently incorporates directionality, it captures the west-to-east flow of the Kuroshio Current. Additionally, it remains robust against spatial nonuniformity in point clouds as it allows a single point to be matched with multiple points along the KCA when necessary (Fig. 3b). Therefore, the metric aligns with the actual physical characteristics and serves as a suitable feature representation of ocean conditions. Meanwhile, the coverage rate of the top-seven ranks reaches approximately two-thirds, roughly corresponding to 1σ assuming a Gaussian distribution. As this coverage rate is deemed acceptable, the number of outputs was set to seven.

Therefore, unless otherwise noted, the values of \({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) and \({\bar{R}}_{{\rm{pum}}}\) presented hereafter are obtained considering the average DTW distance as the KCA similarity metric, with the top-seven-ranked results being used for each test case. The specific values for each test case are provided in the captions of Supplementary Figs. 1–24. The mean values of \(\bar{D}{\rm{pum}}\) and \(\bar{R}{\rm{pum}}\) across all 24 test cases are 181.4 km and 129.7, respectively, which are significantly lower than the corresponding values obtained from random selection. Specifically, these values correspond to 81.1% and 67% of those obtained under random selection, as shown in Fig. 9.

Among the analysis results of all 24 test cases (see Supplementary Figs. 1–24), we display three representative examples, 2014-01-15, 2014-07-15, and 2015-08-15, as Figs. 11, 12, and 13, respectively. In each figure, the top-left panel (a) displays the input KCA and the corresponding true pumice drifting pattern over the given period. The top-right panel (b) shows the most similar KCA based on the average DTW distance metric and the corresponding drifting simulation results. Subsequent rows in both columns display the results in decreasing order of similarity (i.e., increasing average DTW distance), up to the top-seven-ranked matches (b–h).

a Query KCA (black line) and the corresponding true pumice drifting pattern. b–h Top-seven-ranked KCAs (pink lines) with highest similarity to query obtained based on average DTW distance. The corresponding historical drift patterns are shown, with their similarity metrics and evaluation scores (Dpum and Rpum) being provided in legends. Color bar in (h) represents time elapsed since eruption. Averaged evaluation scores are \(({\bar{D}}_{{\rm{pum}}},{\bar{R}}_{{\rm{pum}}})=\left(240.6\,{\rm{km}},81.4\right)\).

In the 2014-01-15 scenario, the KCA gradually shifted southward from the Kii Peninsula, passing directly near Bayonnaise Rocks before abruptly changing direction and flowing northward (Fig. 11a). It then turned northeast to east–northeast off the southern Boso Peninsula, eventually leaving the coastal waters of Japan and heading into the Pacific Ocean. In the corresponding true drifting simulation, most particles generally followed the KCA northward, departing from the coastal waters near the Boso Peninsula, although some particles approached the coastal areas near Hachijojima, Miyakejima, and the Boso Peninsula.

Examining the outputs (Fig. 11b–h), the retrieved KCAs slightly deviate near Bayonnaise Rocks, but all KCAs closely follow the queried KCA within the range 135∘E to 145∘E. Most of the predicted drifting patterns successfully reproduce the initial northward movement of the particles and their later eastward departure from the Boso Peninsula. Notably, in the cases shown in Fig. 11d–f, the simulated pumice particles approach Hachijojima, Miyakejima, and the Boso Peninsula, confirming that the method can capture potential hazards.

In contrast to the previous example, the KCA in the 2014-07-15 scenario (Fig. 12) did not shift southward from the Kii Peninsula but instead flowed directly eastward, passing between Miyakejima and Hachijojima before turning northeast and exiting into the Pacific Ocean. Accordingly, the corresponding true pumice drifting pattern exhibits a southwest to west–southwest drift rather than significant movement in a specific direction.

All output KCA patterns well approximate the true KCA. However, two exceptions (panel (d) and (g) are noted in Fig. 12), the predicted drifting patterns are similar to the true patterns, showing no significant directional movement. Moreover, the predicted drifting patterns in panels (b), (c), and (h) align with the true pattern, showing movement in the southwest to west–southwest direction.

The true KCA patterns in all 24 cases (Supplementary Figs. 1–24) can be roughly categorized into two types exemplified in the above scenarios. In patterns of the first type, the KCA passes close to the Bayonnaise Rocks and the drifting pattern aligns along the axis (see 2015-02-15 (Supplementary Fig. 14), 2015-04-15 (Supplementary Fig. 16), and 2015-09-15 (Supplementary Fig. 21)). In patterns of the second type, the KCA is far from the Bayonnaise Rocks. With few exceptions, these cases exhibit diffuse patterns and no significant directional movement (for example, 2014-09-15 (Supplementary Fig. 9), 2015-01-15 (Supplementary Fig. 13), and 2015-11-15 (Supplementary Fig. 23)). The outputs reasonably predict the overall drifting patterns in both types of cases.

In the 2015-08-15 scenario (Fig. 13a), the KCA shifted significantly southward near the Izu Islands before passing Bayonnaise Rocks and then turning northward along the Izu Islands. Many virtual particles drifted and landed near Hachijojima, Miyakejima, and the Boso Peninsula, the region of high-density maritime traffic, within 7 days. Therefore, this pattern is a critical pattern for hazard assessment. Even in cases of few similar KCA patterns (Fig. 13b–h), the top-ranked patterns drifted toward inhabited islands in the northern Izu Islands or the coastal areas of Honshu, suggesting that the method can effectively estimate hazards in such scenarios.

Application to the latest ocean condition

Bayonnaise Rocks (Myojinsho), the target volcano of this study, has been continuously active since January 20238, necessitating marine warnings and highlighting the importance of the proposed method. Here, we demonstrate the practical application of our model in a case study under the latest conditions. Figure 14 shows the predicted pumice drift from Bayonnaise Rocks when the input comprises the KCA data issued by the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) on December 12, 202432.

On 12 December 2024, the KCA followed a significantly meandering path (Fig. 14a), moving southward from the southern coast of the Kii Peninsula, approaching 30∘N latitude, then flowing northward west of the Izu Islands. Passing just north of Miyakejima, it crossed the Izu Islands and continued northeast off the Boso Peninsula coast. Subsequently, the Kuroshio current exhibited a highly unusual pattern called the Kuroshio extension, traveling further northward to the Sanriku region before turning southward.

Panels (b)–(h) of Fig. 14 display seven similar KCA patterns, identified using the method described in the validation experiments. The estimated KCA patterns do not well match the actual current patterns, as also evidenced by comparing the average DTW distances with those of the validation experiments. Two features dominantly distinguish the estimated paths from the true Kuroshio meandering pattern: (1) the estimated paths are slightly shifted eastward by up to approximately 1 degree longitude from that of the actual KCA, which meanders further west, and (2) the estimated paths do not follow the significant northward movement of the actual Kuroshio current, which extends to the Sanriku off region.

The simulated pumice drifting patterns of all outputs generally indicate a northward movement of the particle clusters, roughly along the Izu Islands. Many of these patterns directly affect the regions near Hachijojima and Miyakejima. Although the low similarity in the KCA patterns suggests limited reliability of the solutions, the outputs highlight a scenario requiring considerable attention during a large-scale pumice release.

Discussion

The proposed KCA-based similarity search method offers considerable advantage in terms of the speed and cost as it eliminates the need for resource-intensive physical simulations. While advanced drifting simulations themselves can generate results within several minutes to hours under optimal computational conditions—such as having preconfigured parameters, sufficient processing power, and minimal data preprocessing requirements—the time required for data integration, validation, and logistical coordination in real-world settings often extends the total time required for the preparation and simulation processes. This highlights the value of the proposed method as a rapid, low-cost solution for initial drift pattern predictions, which can complement detailed simulations when needed. The proposed system performs predictions in <1 min on a standard consumer-grade laptop. Notably, over 95% of this computation time is spent generating visual outputs, primarily rendering extensive particle cloud distributions. Meanwhile, similarity searches, including distance metric calculations, require only few seconds.

In the application to the latest ocean condition, we discussed a recent Kuroshio current path with atypical meandering patterns, called the Kuroshio Large Meander, and a significant northward movement. The latter aberrant current flow, called the Kuroshio extension, reaches the Sanriku off region and is potentially influenced by global warming33. In this extreme case, the low pattern similarity of the KCAs between the input and outputs from past reference datasets, further indicated by the high average DTW distance, suggests that the latest ocean condition is underrepresented in the simulation dataset. As a result, the drift patterns of pumice under these recent ocean conditions cannot be accurately predicted. To resolve this problem, we must enhance the robustness of the drift simulation dataset against variable ocean-current situations. Our present study uses the reanalysis ocean current data up to 2015 according to our previous study17, but increasing the number of drift simulations of recent ocean current patterns-especially during the ongoing Kuroshio meandering-will likely improve the prediction accuracy.

Using KCA similarity as a predictive metric is justified as an initial, low-cost approach for real-time pumice drift prediction. As the dominant oceanographic feature in the region, the KCA strongly influences general drift patterns, enabling rapid predictions without the computational burden associated with incorporating multiple complex variables. However, relying solely on the KCA similarity presents limitations. It does not account for additional oceanographic factors, such as wind, waves, and flow speed, which can substantially affect pumice drift trajectories. Additionally, it may not fully capture local eddy formations or mesoscale oceanic variability, leading to discrepancies between the predictions and observed drifting patterns. Future research will focus on integrating these factors to improve prediction accuracy. This includes incorporating the wind and wave effects for surface drift and using higher-resolution ocean current data to capture mesoscale and submesoscale dynamics. While such multifactor models will be more computationally intensive and logistically demanding, they can provide a more comprehensive representation of pumice drift dynamics.

A critical limitation of the current model is discrepancies between the simulated results and real pumice drift patterns. These discrepancies arise because predictions rely entirely on the drift simulation outcomes.

The proposed system currently uses the drift simulation dataset17, which is based on reanalysis ocean current data with relatively low spatial resolution (0. 1∘ × 0. 1∘) and imposes simple assumptions on pumice behavior.

To improve drift prediction accuracy, future efforts should focus on refining the associated simulations by enhancing the spatial resolution of ocean current datasets, integrating the wind and wave effects at appropriate scales, and accounting for the physical properties of pumice, such as the size distribution and settling dynamics34,35. Bridging the gap between simulations and real-world conditions also necessitates better constraints on physical parameters. This can be achieved through a combination of laboratory experiments on the pumice drift behavior35, satellite-tracked pumice trajectories1,14, and field observations of pumice beaching extents36,37. Systematic validation of the simulation results against these empirical data sources will substantially enhance the reliability of the prediction framework.

The proposed method evaluates the KCA similarity based solely on a single-day observation. While this static approach is effective for short-term predictions (up to approximately several to 10 days), its reliability for longer-term predictions may be limited owing to the dynamic and evolving nature of the KCA. Longer-term predictions are particularly challenging as temporal variations in the KCA affect pumice drift patterns over extended periods. To address this limitation, future research will focus on incorporating sequential KCA data over multiple days, allowing the model to account for temporal trends in the KCA’s trajectory. By integrating such time-series data, the model can better capture changes in KCA dynamics, improving the accuracy and reliability of its longer-term predictions. This dynamic framework represents a notable step toward extending the applicability of the proposed method to long forecast periods while maintaining computational efficiency.

The current model presents only the top-ranked scenarios as the prediction results, without assigning probabilistic confidence levels. However, for quantitative hazard assessments, it is desirable to incorporate uncertainty and perform probabilistic evaluations of prediction reliability. To achieve this, rather than relying solely on ranking criteria, such as the KCA similarity and drift pattern similarity (Dpum), the analysis must account for the complex, nonlinear behaviors and statistical correlations of these similarity measures.. Additionally, the spatial relationship between potential pumice-erupting volcanoes and the KCA can substantially influence drift patterns and prediction accuracy. Therefore, incorporating additional factors, such as the degree of KCA–volcano separation into the input variables, can improve prediction accuracy and reliability. Future research will integrate advanced statistical techniques to assess uncertainty and improve the interpretability of the prediction results. This step will enable the development of a probabilistic framework for drift prediction, enhancing the robustness and reliability of the proposed method.

While the proposed system shows potential for accurately predicting pumice drift in the Izu Islands, its applicability to other regions may be limited. For instance, in areas far removed from the Kuroshio current, such as certain volcanic islands outside its influence, using the KCA as a key feature may not be appropriate. Nevertheless, the system is currently applicable to regions in which the Kuroshio current plays a dominant role in ocean circulation, such as the submarine volcano near Iriomote Island in the Nansei Islands. In such cases, the system can provide valuable predictions; especially, it can assess the potential impact of pumice drift on critical infrastructures along the Honshu coastline.

To mitigate pumice drift damage, the proposed method must be integrated into a broader framework including continuous monitoring and countermeasures. The following steps could be implemented at different levels of urgency: (1) Prior to any volcanic eruptions (normal phase), hazard assessments should be conducted using tools such as the visualization systems developed by us17,38, providing a solid understanding of future potential risks. (2) Once an eruption occurs (emergency phase), the proposed proactive prediction system can provide immediate, real-time estimates of the pumice drift distribution. (3) For large-scale eruptions (severe disaster phase), tandem physical drift simulations would further refine the predictions and guide mitigation efforts. Such a systematic multi-tiered response approach would guide the preparation of countermeasures, thus reducing the impact of pumice drift on coastal areas and maritime traffic.

On September 19, 2024, discoloration of the sea and small amounts of white pumice were observed near Sumisujima Island, ~50 km south of Bayonnaise Rocks, triggering an eruption warning by the JMA and the JCG8. We immediately prepared a report based on the proposed method and submitted it to the Headquarters for Volcanic Research Promotion in Japan, outlining potential scenarios in the event of significant pumice drift. Although no substantial eruptions involving pumice emissions have occurred since then, the proposed proactive system demonstrates effectiveness against such “false alarms” by conserving human resources, which are needed for timely physical simulations after sudden eruptions.

Methods

Distance metrics

Two curves A and B are expressed as ordered sets A = {a1, a2, …, am} and B = {b1, b2, …, bn}, respectively, where m and n are the numbers of observed points in A and B, respectively. In addition, we calculate the distance d(A, B) on the map utilizing the Haversine formula, which computes the distance between two points using differences between their latitude and longitude coordinates.

Hausdorff distance

The Hausdorff distance is defined as

where d(a, b) represents the distance between points a ∈ A and b ∈ B. The two parts of this definition are interpreted as follows:

-

\(\mathop{\max }\nolimits_{a\in {\boldsymbol{A}}}\mathop{\min }\nolimits_{b\in {\boldsymbol{B}}}d(a,b)\): For each point a in A, find the closest point b in B, then take the maximum of these minimum distances over all points in A.

-

\(\mathop{\max }\nolimits_{b\in {\boldsymbol{B}}}\mathop{\min }\nolimits_{a\in {\boldsymbol{A}}}d(b,a)\): Similarly, for each point b in B, find the closest point a in A, then take the maximum of these minimum distances over all points in B.

The Hausdorff distance dHaus(A, B) then takes the greatest of these two maximum distances, capturing the maximum proximity discrepancy between the two curves (see Fig. 3a).

Fréchet distance and average DTW distance

The DTW distance between two sequences A = {a1, a2, …, am} and B = {b1, b2, …, bn} is recursively defined as dDTW(A, B) (Fig. 3b). Let D(i, j) represent the cumulative cost of aligning the first i elements of A with the first j elements of B:

with boundary conditions

and initial condition D(0, 0) = 0. The function d(ai, bj) represents the distance between points ai ∈ A and bj ∈ B. The average DTW distance is then given by

where P is the length of the path from pair (a1, b1) to pair (am, bn). A coupling L = (l1, l2, …, l∣L∣) between the indices of A and B defines a sequence of pairs li = (pi, qi) such that:

-

1.

p1 = 1, q1 = 1 (the start points of A and B),

-

2.

pk = m, qk = n (the endpoints of A and B),

-

3.

pi+1 = pi + 1 or pi,

-

4.

qi+1 = qi + 1 or qi.

The sequence of index pairs, L, is called a dynamic warping path in the distance matrix d(ai, bj) (Fig. 3d) and is determined via dynamic programming (see Eq. (3)).

The discrete Fréchet distance dFrec(A, B) between two ordered sets of points A and B is defined in terms of the coupling L = (l1, l2, …, l∣L∣) between the indices of A and B. The discrete Fréchet distance is thus defined as

where \(d({a}_{{p}_{i}},{b}_{{q}_{i}})\) is the distance between points \({a}_{{p}_{i}}\in {\boldsymbol{A}}\) and \({b}_{{q}_{i}}\in {\boldsymbol{B}}\). Note that the Fréchet distance describes the maximum distance between two curves along the dynamic warping path (see Fig. 3b,d).

Wasserstein distance

Consider two unordered point sets A = {a1, a2, …, am} and B = {b1, b2, …, bn} and assume that m = n for simplicity (that is, both sets contain the same number of points). The Mallows distance (or 2-Wasserstein distance) dWS(A, B) is then defined as

where d(ai, bπ(i)) represents the distance (e.g., Euclidean distance) between points ai ∈ A and bπ(i) ∈ B, and Sn denotes the set of all permutations π of {1, 2, …, n}. The sum\(\mathop{\sum }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{n}d{({a}_{i},{b}_{\pi (i)})}^{2}\) computes the total squared distance over a matching π. The goal is to find the permutation π that minimizes the total squared distance between the points in A and those in B. The square root of this minimum gives the Mallows distance (see Fig. 3).

When generalized to m ≠ n, this definition is extended using a probabilistic mass transportation framework. Each point set is treated as a discrete probability distribution, where weights are assigned to points such that the total mass for each set equals one. Hereafter, we refer to the above-defined Marrows distance as the Wasserstein distance.

Pumice drift simulations

The drift simulations assume pumice ejections from seven submarine volcanoes near the Japanese archipelago17. The data contain the daily positions of virtual 49,000 pumice particles released on the 15th of each month between 1982 and 2015. Each particle is moved by a random-walk of a Lagrangian particle in a velocity field of the ocean current. This velocity field uses the ocean reanalysis dataset of the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA)31, which reproduces the historical ocean current and meteorological data. The temporal resolution is 1 day and the horizontal spatial resolution is 0.1∘ × 0. 1∘. The ocean surface layer is represented by the depth of the pumice particles (assumed constant at 0.5 m). The particle movement is influenced not only by the ocean currents but also by eddy diffusion, waves, and surface winds. To account for these additional movements, we set a diffusion coefficient of 1000 m2/s17. The computational time for each scenario (365 days after the eruption) was ~1 day using a supercomputer at JAMSTEC, called Earth Simulator 4.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Code availability

Some of the code will be available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Jutzeler, M. et al. On the fate of pumice rafts formed during the 2012 Havre submarine eruption. Nat. Commun. 5, 3660 (2014).

Jutzeler, M. et al. Ongoing dispersal of the 7 August 2019 pumice raft from the Tonga arc in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e1701121 (2020).

Tada, N., Nishikawa, H., Ichihara, H., Watanabe, H. K. & Kuwatani, T. Drift of an ocean bottom electromagnetometer from the Bonin to Ryukyu Islands: estimation of the path and travel time by numerical tracking experiments. Earth Planet Space 73, 224 (2021).

Yoshida, K. et al. Variety of the drift pumice clasts from the 2021 Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba eruption, Japan. Island Arc. 31, e12441 (2022).

Maeno, F. et al. Seawater-magma interactions sustained the high column during the 2021 phreatomagmatic eruption of Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 260 (2022).

Oikawa, T., Ikegami, F. & Watanabe, S. Eruption styles and source volcanoes for drifting pumice deposited along the Nansei Islands, Southwest Japan (in Japanese). Bull. Volcanol. Soc. Japan 68, 171–187 (2023).

Japan Coast Guard. Regarding the Floating Objects Near Torishima Observed on October 20th (in Japanese). https://www.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/info/kouhou/post-1041.html (2023).

Japan Meteorological Agency. Volcanic Warning / Forecast by Japan Meteorological Agency. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/multi/volcano/index.html?lang=en (2024).

Van Sebille, E. et al. Lagrangian ocean analysis: fundamentals and practices. Ocean Model. 121, 49–75 (2018).

Kuroda, H. History, current status, and future vision of particle-tracking simulation applied to marine biology, fisheries science, and ecological engineering around Japan. Fisheries Sci. 89, 129–146 (2023).

Bryan, S. E. et al. Pumice rafting and faunal dispersion during 2001–2002 in the Southwest Pacific: record of a dacitic submarine explosive eruption from Tonga. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 227, 135–154 (2004).

Bryan, S. E. et al. Rapid, long-distance dispersal by pumice rafting. PloS One 7, e40583 (2012).

Chang, Y.-L. K., McIntosh, I. M., Miyama, T. & Miyazawa, Y. Projection of August 2021 pumice dispersion from the Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba eruption in the western North Pacific. Sci. Rep. 13, 3945 (2023).

Iskandar, M. R. et al. Tracking the pumice rafts from the Fukutoku-Okanoba submarine volcano with satellites and a Lagrangian particles trajectory model. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 193, 115254 (2023).

Chiang, Y., Huang, P.-C. & Yang, Z.-Y. Assessment of the Fukutoku-Okanoba pumice rafts dispersion model using the daily collection data from nuclear power plants seawater intake system. Nuclear Eng. Design 427, 113448 (2024).

Miyama, T. Simulation of drifting pumice from the Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba submarine volcano (in Japanese). J. Japan S. Mar. Surveys Technol. 35, 19–21 (2023).

Nishikawa, H., Kuwatani, T., Tada, N. & Kayama Watanabe, H. Simulated distributions of pumice rafts in Japan following eruptions at volcanic islands and submarine volcanoes. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 10, 1–20 (2023).

Guttman, A. R-trees: a dynamic index structure for spatial searching. Proc. 1984 ACM SIGMOD International Conference on Management of Data 47–57 (1984).

Li, M. et al. Deep learning for approximate nearest neighbour search: a survey and future directions. IEEE Trans. Knowledge Data Eng. 35, 8997–9018 (2023).

Agrawal, R., Faloutsos, C. & Swami, A. Efficient similarity search in sequence databases. Foundations of data organization and algorithms. 4th International Conference, FODO’93 Chicago, Illinois, USA, October 13–15, 1993 Proceedings 69–84 (IEEE, 1993).

Bridson, M. R. & Hafliger, A. Metric Spaces of Non-Positive Curvature. Grundlehren der Mathematischen Wissenschaften 1st edn, Vol. 643 (Springer, Berlin, Germany, 2010).

Alt, H. & Godau, M. Computing the Fréchet distance between two polygonal curves. Int. J. Comput. Geom. Appl. 5, 75–91 (1995).

Sakoe, H. & Chiba, S. Dynamic programming algorithm optimization for spoken word recognition. IEEE Trans. Acoustics Speech Signal Proc. 26, 43–49 (1978).

Villani, C. Optimal Transport, Old and New 2009th edn, Vol. 976 (Springer, 2008).

Keogh, E. & Kasetty, S. On the need for time series data mining benchmarks: a survey and empirical demonstration. Data Mining Knowledge Discov. 7, 349–371 (2003).

Keogh, E., Chu, S., Hart, D. & Pazzani, M. Segmenting time series: a survey and novel approach. Data Mining Time Series Databases 57, 1–22 (2004).

Fu, T.-C. A review on time series data mining. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 24, 164–181 (2011).

Ren, F. et al. An objective track similarity index and its preliminary application to predicting precipitation of landfalling tropical cyclones. Weather Forecasting 33, 1725–1742 (2018).

Hokson, J. & Kanae, S. An alternative similar tropical cyclone identification algorithm for statistical TC rainfall prediction in the Western North Pacific. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 129, e2023JD040246 (2024).

Japan Coast Guard. Japanese Marine Volcano Database of the Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department of Japan Coast Guard (JHOD)). https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/kaiikiDB/list-2.htm (2023).

Japan Meteorological Agency. National Catalogue of the Active Volcanoes in Japan, 4th Edition. https://www.data.jma.go.jp/svd/vois/data/tokyo/STOCK/souran_eng/menu.htm (2013).

Japan Coast Guard. Quick Bulletin of Ocean Conditions: The Ocean Current (Kuroshio etc.) and Sea Surface Temperature Around Japan. https://www1.kaiho.mlit.go.jp/KANKYO/KAIYO/qboc/index_E.html (2024).

Sakamoto, T. T. et al. Responses of the Kuroshio and the Kuroshio Extension to global warming in a high-resolution climate model. Geophys. Res. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1029/2005GL023384 (2005).

Asami, M. & Takahashi, C. Drift prediction of pyroclasts released through the volcanic activity of Fukutoku-Okanoba into the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 186, 114402 (2023).

Takeuchi, S., Ishige, K., Uesawa, S. & Suwa, Y. Unsinkable, long-drifting, millimeter-sized pumice of the 2021 eruption of Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba submarine volcano. Prog. Earth Planetary Sci. 11, 47 (2024).

Yoshida, K., Maruya, Y. & Kuwatani, T. Chocolate-chip cookie-like pumice from the 2021 Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba eruption: views from SNS-related geology (in Japanese with English Abstract). J. Mag. Mineral. Petrol. Sci. 51, 220412 (2022).

Ishimura, D. & Hiramine, R. Dispersion, fragmentation, abrasion, and organism attachment of drift pumice from the 2021 Fukutoku-Oka-no-Ba eruption in Japan. Prog. Earth Planet. Sci. 12, 5 (2025).

Kuwatani, T., Kitao, K., Nishikawa, H., Tada, N. & Watanabe, H. K. Visualization of simulated paths of drifting pumices using point cloud PNG:towards the construction of hazard assessment system for drifting pumices (in Japanese with English Abstract). Geoinformatics 34, 61–68 (2023).

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the Editors. This work was partially supported by JST CREST (JPMJCR1761); JSPS KAKENHI (JP22K18742; 22H00251; 24K01139) and the Cooperative Research Program of the Earthquake Research Institute, University of Tokyo (ERI JURP 2022-B-06; 2024-B-01). All map figures in this study utilize MATLAB’s ’grayland’ basemap, which is based on Natural Earth data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K.: Writing—Original draft, Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal Analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization; H.H.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology; H.N.: Writing—review and editing, Data curation, Investigation, Validation, Funding acquisition,; S.A.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kuwatani, T., Hino, H., Nishikawa, H. et al. Data-driven proactive prediction of pumice drifting patterns using similarity search of the Kuroshio current axis. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 34 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00088-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00088-1

This article is cited by

-

From observation to understanding: rethinking geological hazard research in an era of advanced technologies

npj Natural Hazards (2025)