Abstract

Climate change is worsening coastal hazards, elevating the need to mitigate and adapt to future warming and sea-level change. A key question is how future warming relates to coastal impacts in terms of adaptation costs and economic damages, and the potentially unequal distribution of these impacts globally. We use an integrated modeling framework to generate estimates of future coastal adaptation costs and damages, discounted through the year 2150, at multiple global warming thresholds. As warming crosses the 1.5 °C threshold, we find that high-end (95th percentile) coastal damages nearly double, from 1.3 T to 2.3 T US$. Beyond 2.5 °C warming, low-end (5th percentile) damages increase from 1.2 T to 1.6 T US$ and the Global South faces disproportionately high damages as a percentage of regional GDP. Given the plausibility of 2.5 °C warming in even SSP2-4.5, these results highlight the importance of emissions reductions to avoid sizable and inequitable increases in coastal impacts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change poses severe risks to people and property around the world, driven in part by warming temperatures, increasing frequencies of extreme weather, and rising sea levels1. Sea-level rise poses an existential threat to millions of people worldwide, as previous work has found that tens of millions of coastal residents will be displaced by sea-level rise2, with one estimate projecting that more than 1% of the global population will be displaced by sea-level rise even in the moderate Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP) 4.5 scenario3. These studies considered a broad range of socioeconomic and sea level scenarios and model structural assumptions for the conditions under which coastal populations relocate in response to sea-level rise. The level of population and asset exposure to coastal hazards are also likely to rise, as the frequency and severity of coastal extreme sea levels are also expected to increase with climate change1,4,5. These exacerbating hazards lead to severe risks for coastal areas, and highlight the importance of stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions to limit the negative impacts from global warming6.

Given the extreme hazards driven by sea-level rise over the coming decades, there is a need to examine how coastal communities can mitigate future damages through adaptation. Large-scale studies of coastal adaptation and impacts decompose these costs and damages across different categories, generally including costs associated with constructing new flood defenses (e.g., dikes, levees, or seawalls, here generally referred to as “seawalls” for simplicity), costs associated with relocating and potentially constructing new infrastructure further inland, and losses or damages associated with flooding, inundation, and wetland loss (including losses of property and lives) (e.g., refs. 7,8,9,10).

Many climate impact studies employ a common set of paired socioeconomic/emissions scenarios (e.g., the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Representative Concentration Pathways, SSP-RCP11,12). For example, ref. 9 uses global mean sea-level projections for RCP4.5 and RCP8.5 to find that, without additional adaptation, global coastal damages will increase 150-fold between 2010 and 2080. Similarly, Diaz7 and Wong et al.10 use a coastal impacts and adaptation model and SSP1-2.6, 2–4.5, and 5–8.5 to quantify the benefits of coastal adaptation measures on a global scale, and characterize the importance of accounting of uncertainty in their simulations. Other studies of climate impacts have been framed in terms of temperature thresholds (e.g., the 1.5 °C or 2 °C limits established in the Paris Climate Agreement13), often in conjunction with the SSP-RCP scenarios. For example, recent studies have used warming scenarios of 1.5 °C and 2 °C to examine heat-related mortality14, and have used both temperature thresholds and the SSP-RCP scenarios to find that damages of nearly 3% of total global GDP can result from the sea-level rise associated with warming in excess of 2 °C15.

Many more studies have examined both the feasibility of and impacts from limiting warming to different global warming thresholds. This can be framed in terms of how much warming “inertia” is locked into the climate system based on greenhouse gas emissions to date (e.g., refs. 16,17,18,19). For example, Dvorak et al.20 find that we are likely already committed to warming of at least 1.5 °C. And even if warming is limited to 1.5 or 2 °C, extreme sea levels are poised to become much more common21. In the optimistic case of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions until 2300, we may still be committed to global sea-level rise between 0.7 and 1.2 m22. Further, those authors find that sea-level rise of more than 1.5 m is possible with only 2 °C of warming. Relatedly, even if nations adhere to the pledged Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement until 2030, these greenhouse gas emissions would still lead to an additional 1 m of sea-level rise by 230023. These results for committed sea-level rise beyond the next century have important implications for adaptation needs on a multi-century timescale, as even 0.5 m of sea-level rise can pose an extreme threat to low-lying coastal areas24,25. Our study only considers hazards and adaptation to the year 2150, but we emphasize the need for continued monitoring and adaptive action.

These previous studies provide ample evidence as to the global warming and sea-level commitments from past greenhouse gas emissions. A number of foundational works that estimate coastal impacts, including adaptation costs and population exposure under climate warming thresholds (e.g., refs. 15,21,26). However, key gaps remain, including allowing planned relocation as an adaptation strategy and examining a range of temperature thresholds that includes high-end warming27. This work fills this gap by using a coastal impacts and adaptation model to estimate the coastal economic losses and adaptation costs at a variety of plausible global warming thresholds. While sea-level thresholds (e.g., 0.25 m of local sea-level rise) can be more directly interpretable in terms of adaptation policy development, local sea-level change and hazards are subject to numerous complexities and uncertainties. Instead, we use global warming thresholds to relate higher-level policy goals to coastal impacts that are interpretable in as local costs and damages. Further, projections of global temperature change are readily available based on either presumed emissions trajectories and/or carbon cycle modeling. Finally, as argued by ref. 15, linking global warming thresholds to coastal economic impacts can be useful to explore the relationship between climate drivers of hazard and coastal risks.

In this work, we address these research needs by using a modular modeling framework to generate a large ensemble of future states-of-the-world (SOW), accounting for carbon cycle, global mean surface temperature (GMST), global mean sea level (GMSL, downscaled to local sea-level rise (LSLR)), and socioeconomic uncertainties. We bin these SOW into groups at different global warming thresholds and examine overall coastal adaptation costs and expected damages using the MimiCIAM coastal impacts and adaptation model10. In reporting our results, we use the general term “adaptation costs and losses/damages” or simply “costs” to refer to the main outputs of interest from MimiCIAM, and our overall model chain. This includes both true costs for adaptation implementation (e.g., constructing a seawall) as well as potential future damages (e.g., flood damages), as both are a form of cost incurred as a result of adaptation, or a lack thereof. These computational experiments offer important insight into how climate policy decisions and efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions and consequent warming can reduce—but not eliminate—damaging effects to coastal areas.

Results

Mitigating warming dramatically reduces potential for high-end damages

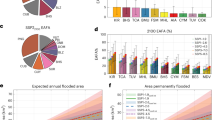

We find that median coastal adaptation costs and damages are substantially lower in a world with no more than 2.5 °C of warming relative to pre-industrial, as compared to greater than 2.5 °C of warming (Fig. 1). There are two large-scale changes relative to a ≤1.5 °C world as global warming levels increase. First, when warming reaches the 2 °C threshold (1.5–2.5 °C), the high-end adaptation costs increase dramatically to $2.3 trillion from $1.3 trillion in a ≤1.5 °C world (where high-end costs are given by the upper 95th percentile). At these lower warming levels, however, the high-end costs are primarily affected by warming, whereas the median costs only increase gradually. Median damages in the lowest two temperature bins are $1.2 trillion (≤1.5 °C) and $1.5 trillion (2 °C). In the second large-scale change, with warming at the 3 °C (2.5–3.5 °C) or >3.5 °C levels, all costs are substantially higher than the ≤1.5 °C world. The median total costs at these higher warming levels are $2.1 trillion (3 °C) and $2.6 trillion (>3.5 °C).

Sea-level rise and associated adaptation costs at different warming levels

Sea-level rise is a critical link between warming levels and future coastal hazards. To better understand the changing distributions of coastal adaptation costs and damages at different warming levels, we plot the distributions of the costs and losses relative to the distributions of global mean sea-level rise, pooled by the warming thresholds (Fig. 2). Unsurprisingly, there is a clear positive relationship between global mean sea-level change and future coastal adaptation costs. The marginal distributions for total damages in Fig. 2 show distributions of costs/losses that have similar lower tails between the ≤1.5 °C and 2 °C thresholds (5th percentiles are $1 trillion and $1.2 trillion, respectively). At the 3 °C and >3.5 °C levels, however, these lower tails dramatically increase ($1.6 trillion and $2.2 trillion). Furthermore, the marginal distributions of damages at or above the 3 °C threshold are relatively symmetric and centered much higher than the heavily right-skewed distribution of damages for the 2 °C threshold. This result demonstrates that at warming >2.5 °C, sizable damages are no longer an unlikely tail event, they are the norm. On the other hand, restricting warming to ≤2.5 °C greatly increases the relative odds of lower coastal adaptation costs and losses.

The substantial overlap between the distributions of sea-level rise and adaptation costs at different warming thresholds indicates that we cannot necessarily rely on global mean surface temperature as a direct signpost of impending damages. This is particularly true of high-end damages. Among the SOW with total NPV of costs greater than the 95th percentile overall of $2.7 trillion (250 SOW out of 5000 total; Supplementary Fig. 7), unsurprisingly, many are from the >3.5 °C threshold (125 SOW), but a sizable number are from the 3 °C threshold (109 SOW). This is attributable to the fact that there are many more simulations in the 3 °C threshold than the >3.5 °C one (Table 1). The probabilities of exceeding $2.7 trillion in global costs, conditioned on each temperature threshold, are 1% (2 °C), 5% (3 °C), and 32% (>3.5 °C); no simulations with warming below 1.5 °C exceeded $2.7 trillion in global damages. Critically, the presence of 2 °C SOW in the upper-right of Fig. 2 illustrates that high-end adaptation costs are possible even in a 2 °C warming world.

Unequal distribution of damages

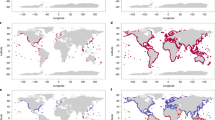

A picture of inequality emerges by decomposing the projected coastal adaptation costs and damages across different global regions (Fig. 3). At warming levels below 1.5 °C, all seven of the global regions incur coastal adaptation costs between about 1–3% of their regional GDP (Fig. 3, left-most cluster of bars). However, above 2.5 °C, three regions consistently suffer disproportionately higher damages: Sub-Saharan Africa (1.2× and 1.1× global average damages as a percentage of GDP at the 3 °C and >3.5 °C levels), Latin America and the Caribbean (1.6× and 1.5× global average), and East Asia and the Pacific (1.4× at both thresholds). These higher-damage regions are predominantly in the Global South and include many developing countries. While the Global South tends to suffer higher-than-global-average coastal damages and adaptation costs at elevated warming levels, Europe and Central Asia see much lower damages (0.8× at both thresholds). The remaining three regions experience adaptation costs and damages that are roughly equal to global average: North America (1.1× and 1× global average), Middle East and North Africa (0.9× and 1× global average), and South Asia (1× and 1.1× global average).

The regional inequality in coastal adaptation costs and damages increases as the global warming threshold increases from a 2 °C world to a 3 °C one. Damages for Europe and Central Asia, North America, and Sub-Saharan Africa increase by less than the global average of 0.85% of their regional GDP, while South Asia faces an increase about equal to global average. The remaining regions (Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and the Pacific, and Middle East and North Africa) face additional damages of about 1% or more of regional GDP at the 3 °C temperature threshold as compared to the 2 °C threshold. Two regions—Latin America and the Caribbean and East Asia and the Pacific—both face disproportionately higher costs as a proportion of their regional GDP and face disproportionately higher increases in costs as the level of global warming increases.

Discussion

Here, we have related future climate changes at different global warming thresholds to their corresponding coastal impacts and adaptation costs. We find that there is a dramatic increase in high-end coastal damages, as seen by the increase in the length of the upper error bars in Fig. 1 for temperature thresholds above 1.5 °C. This increase in the upper tail of the distribution of coastal damages corresponds to the potential onset of rapid Antarctic ice sheet disintegration, as there is evidence that this tipping point can be triggered even below 2 °C28,29. In addition, above 2.5 °C warming, not only do high-end damages increase, but the median damages increase as well (Fig. 1). This demonstrates that (i) coastal damages at the 1.5 °C warming level are already locked in, (ii) a 2 °C future (1.5–2.5 °C warming) commits us to more severe high-end coastal damages, and (iii) warming above that commits us to a harsh future of increased coastal damages all-around. Such levels of warming are well within the latest set of Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) projections, particularly for SSP3–7.0 and SSP5–8.5, but also for the more moderate scenario SSP2–4.530. This illustrates our societal choice between paying now to reduce warming and mitigate future damages or paying later for a lack of mitigation through high-end coastal damages, including losses of both assets and lives.

Our results for how varying levels of climate warming affect future coastal damages (Fig. 3) use the lens of coastal adaptation to affirm previous results that show that those who stand to suffer the most from climate change are often those who did the least to cause it24,31,32. This is consistent with the results of Jevrejeva et al.15, who found that high-income countries tended to have lower projected flood costs, and attributed this to those countries’ relatively higher current levels of coastal adaptation. Indeed, the temperature threshold at which the unequal impacts become most apparent (3 °C) is well in line with recent work by the IPCC regarding the distribution of climate impacts as a reason for concern (ref. 24, their Fig. SPM.3) and past work that highlights the need for improved knowledge of ice sheet contributions to future sea levels to better constrain the sea-level projections associated with these high-warming scenarios33. We can better understand the regional inequality in 2 °C versus 3 °C damages by varying the underlying socioeconomic scenario. By changing from SSP4 (main text) to SSP2, the differences in 2 °C to 3 °C changes in %GDP damages track the changes in long-term GDP per capita for each region (Supplementary Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. 9; also, e.g., Supplementary Material of ref. 10). GDP and GDP per capita are tied tightly to damages within the MimiCIAM model structure, for example, through value of statistical life for flood losses, or through capital stock valuation, which affects the relocation costs and storm damages. This explanation is consistent with the argument made by Jevrejeva et al.15 that higher-income regions have greater existing adaptation measures and greater ability to implement new adaptation measures, as compared to lower-income regions.

While the simulations presented here are focused on century-scale warming, temperature stabilization over the course of multiple centuries or millennium timescales are important considerations22,34,35,36,37. However, modeling coastal impacts over such long timescales would involve many strong and interrelated assumptions regarding such climate changes, socioeconomic and technological development, climate change mitigation policies, and coastal adaptation decision-making. For example, this model structure misses any feedbacks between coastal damages and subsequent changes in policies surrounding mitigation or further adaptation. Furthermore, while the sea level response to global warming has a multi-century timescale19,38,39, the economic discounting in MimiCIAM means that climate impacts that occur centuries or more in the future hold almost no present-day economic value. For example, using MimiCIAM’s default discount rate of 4%, costs incurred 100 years from now are valued at 2% of their present-day value. While there are deep uncertainties surrounding future emissions and socioeconomic development, sea-level rise poses an existential threat, particularly for Arctic and low-lying coastal communities, even in low-emissions future scenarios such as RCP2.624. Indeed, the greenhouse gas emissions over the 21st century will lead to potentially multi-meter sea-level contributions from the major ice sheets over the next several centuries40, driving the need for adaptation responses that consider multi-century timescales19,41. Given the sizable uncertainties involved, robust decision-making and dynamic adaptive pathways approaches offer a way to navigate the need for decision-making under deeply uncertain conditions2,42.

Despite the inherent limitations and assumptions surrounding socioeconomic uncertainties in assessments of future coastal impacts from climate change, our results are in line with previous work. Hinkel et al.43 examined cases in which coastal areas construct seawalls to maintain constant levels of protection and in which coastal areas construct enhanced protection to account for changing demand for safety (e.g., changes in assets or population). With enhanced adaptation, that work finds annual coastal flood damages of between about 10–75 billion 2005$US (cf. their Fig. 3). Further, without additional adaptation, Jevrejeva et al.15 report annual flood costs by 2100 of 10.2 trillion $US per year with 1.5 °C of warming, and up to 11.7 trillion $US per year with 2 °C of warming. As might be expected, our results fall between these two studies, with annual flood costs in our analogous enhanced adaptation pathway of about 49 billion 2010$US per year (with 330 $US overall annual costs and damages in 2100). Our main text results use a discount rate of 4%, but this number is not discounted for parity with the two studies cited in this paragraph. That our results are in agreement with, though on the high side, Hinkel et al.43 is unsurprising, given that both studies employ DIVA and the GMSL projections in our work are higher. The maximum 2100 GMSL among their ensemble was about 1.2 m (relative to 1985–2005), while the maximum in our ensemble is about 2.8 m (relative to 1995–2014; 95th percentile is 1.4 m). Our GMSL projections are consistent with those in IPCC AR6 (Supplementary Fig. 4), reflecting updated knowledge since the groundbreaking work of ref. 43. Specifically, the increased upper tail in the distribution for GMSL is driven by high-end, low-confidence estimates of future Antarctic ice sheet contributions to sea-level change44. Importantly, while our results for overall numbers of sea level-driven migrants by the year 2100 (13–45 million people) match results from a similar recent study (17–72 million people)2, the prospect of triggering rapid, widespread Antarctic ice sheet disintegration drives a bifurcation in possible futures for coastal migration. Specifically, in a supplemental analysis, we find that triggering the tipping point for rapid Antarctic ice sheet disintegration is associated with more than doubling the number of coastal residents who migrate to avoid hazards from coastal flooding (17 million migrants compared to 36 million migrants; Supplementary Fig. 10). This result underscores the need to develop adaptation signposts of impending sea-level rise (e.g., monitoring the rate of sea-level change) and continually update coastal adaptation plans as new information becomes available.

As with all modeling studies, the results presented here are conditioned on the models employed, the data used to calibrate those models, and the assumed pathways of socioeconomic change and greenhouse gas emissions. This work avoids the issue of assigning implicit and subjective prior probabilities to the SSP-RCP scenarios, but still relies on the SSP4 population and GDP pathways. This was chosen to best match the output from our stylized model for greenhouse gas emissions45. The assumptions underlying our modeled geophysical change yield projections of sea-level rise commitment that are broadly consistent with the work of Mengel et al.22. That work found that even when global warming is limited to below 2 °C, median GMSL by 2300 can still exceed 1.5 m. In our ensemble, among the SOW where warming is below 2 °C, about 4% of these scenarios yield GMSL that exceeds 1.5 m by 2300. While this is notably lower than the median (50%) found by ref. 22, this is explained by our use of a probabilistic model for greenhouse gas emissions, instead of pooling SSP-RCP scenarios. Specifically, our modeling framework accounts for the relatively lower likelihood of high-end scenarios like SSP5–8.5 as compared to more moderate scenarios like SSP2–4.5.

These caveats notwithstanding, our results expand on previous studies that relate future global warming levels to committed changes in future sea levels (e.g., refs. 19,22) by linking the projected sea-level changes to their coastal impacts. Based on the changes seen in the 95th percentile of the distributions of adaptation costs and losses (Fig. 1), we find that as warming increases above 1.5 °C, high-end coastal impacts are more severe. Based on changes in the distributions’ medians, beyond 2.5 °C warming, all damages are dramatically higher than a world where warming was limited to 1.5 °C. These levels of warming are all plausible. We find that the impacts of continued and excessive global warming are unevenly distributed, with Latin America and the Caribbean, East Asia and the Pacific, and Sub-Saharan Africa suffering damages that are greater than the global average, while Europe and Central Asia face damages that are much lower than global average. Beyond 2.5 °C warming, these inequalities grow. In summary, at high levels of global warming, the negative coastal impacts are felt disproportionately by the Global South and many developing countries. Overall, these results further highlight the importance of mitigating future greenhouse gas emissions in order to limit warming and consequent inequity in coastal economic damages, as well as the importance of incorporating potentially high-end hazards into adaptation decision-making.

Methods

Our model chain represents (1) uncertainty in greenhouse gas emissions, (2) uncertainty in the carbon cycle, which yields atmospheric CO2 concentrations; (3) uncertainty in the climate system, which yields global surface temperatures; (4) uncertainty in the major components of global mean sea level, which is then downscaled to local mean sea level; and (5) uncertainty in socioeconomic factors related to the impacts and adaptation costs associated with rising coastal sea levels. The model chain (Fig. 4) links atmospheric CO2 emissions from an emissions emulator to estimate temperature and ocean heat uptake via SNEASY46, a simple, nonlinear carbon cycle and Earth system model. Global mean surface temperature (GMST) and ocean heat are then used by our sea-level model, MimiBRICK47, to estimate global mean sea-level (GMSL) change, which is downscaled to local sea-level rise (LSLR). Finally, local sea-level change is used as input to our coastal impacts model, MimiCIAM10, to estimate future coastal adaptation costs and losses due to coastal flooding. The main model outputs of interest in the present study are global mean surface temperature, global and local sea-level change, and local coastal adaptation decisions, costs, and losses due to coastal hazards. Some outputs also serve as inputs to other model components, such as global mean surface temperature, which is output from one model component and input to another.

All models in our model chain are coded in the Mimi integrated modeling framework48 using the Julia programming language. The Mimi framework provides a common structure for component models within a larger system model. This enables efficient, simple, and transparent exchange of information between model components, and consistent treatment of model parameters and their uncertainties. Importantly, the relatively low computational cost of running our semi-empirical models enables a detailed accounting of uncertainty, but this comes at the cost of an explicit spatial representation of the various processes that contribute to sea-level change globally and feedbacks between those processes49. However, the focus of the present work is to examine how these uncertainties affect coastal economic impacts from climate change, binned by global warming thresholds. As such, it is preferable to have a detailed statistical model and accounting of uncertainty, as compared to a more detailed physical model prescription (e.g., process-based models).

Carbon cycle uncertainties

We use a simple parametric model to represent uncertainty in the carbon cycle and future CO2 emissions45. CO2 emissions (GtCO2/yr) in year t, q(t), are parameterized by three parameters: τ, a year in which emissions are assumed to peak; γg, an emissions growth rate; and γd, an emissions decline rate. Before year τ, emissions are assumed to grow quadratically and after year τ, emissions are assumed to decrease logistically to 0.

This mathematical representation of future emissions is intended to follow the general structure of the SSP-RCP scenarios, including near-term emissions growth and an uninterrupted downward trend in emissions once they peak. The flexibility of this approach allows us to generate rapidly increasing near-term emissions trajectories (such as SSP5–8.5), trajectories that produce net-zero emissions prior to 2050, and trajectories where emissions plateau for a long time. While this framework omits negative emissions, which limits our ability to explore particularly low sea levels, our simple model is in broad agreement with the CO2 emissions pathways in the SSP scenarios (see ref. 45 Fig. 2). Specifically, the ensemble median tracks well with emissions under SSP2–4.5 and 4–6.0. SSP5–8.5 sits toward the high end of the distribution of ensemble members’ CO2 emissions pathways, which is consistent with its interpretation as a low-probability high-end scenario50. We take SSP4 as our baseline scenario for the socioeconomic pathways in the simulations presented here, because it offers the best agreement between the cumulative emissions by 2100 among the standard SSP-RCP scenarios and the underlying ensemble of ref. 45. We provide results for supplemental simulations using SSP2 because SSP2–4.5 also agrees well with our ensemble and represents a middle-of-the-road scenario. Because our model structure does not allow for negative annual net emissions, caution should be used when interpreting and comparing our results against those from SSP1–1.951,52,53,54. Our model accounts for non-CO2 greenhouse gas forcings by sampling their radiative effect from the nearest SSP trajectory.

In our model chain, we use the CO2 emissions pathways from this emulator as input into a Simple Nonlinear Earth System Model (SNEASY46). We use a sample of 5000 simulations out of the full ensemble of 100,000 simulations. Our results with a smaller ensemble of 4000 samples are unchanged relative to our sample of 5000 simulations, so we conclude that any larger of a sample would be unnecessary because our results would not appreciably change (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Our approach avoids the issue of assigning weights, implicitly or explicitly, to the various SSP-RCP scenarios. For example, a simple pooling across SSP-RCP scenarios applies an implicit equal-weighting scheme and can lead to confusion in applying a probabilistic interpretation to the results55. Further, the use of our simple parametric emissions model yields representations of global sea-level and temperature change that agree well with the latest projections in the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report (AR644; see Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 4).

Sea-level change

The SNEASY model yields ocean heat uptake and global mean surface temperatures as output. These serve as inputs to our sea-level model. We use the modular Building Blocks for Relevant Ice and Climate Knowledge (BRICK) model for sea-level rise, coded in the Mimi integrated modeling framework (MimiBRICK47). MimiBRICK is a simple, mechanistically-motivated semi-empirical model for sea-level change, and includes potential rapid ice sheet warming responses that are in broad agreement with the sea-level projections in AR6 (Supplementary Fig. 4). These sea-level projections account for the major contributors to global mean sea-level change, including the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, glaciers and ice caps, thermal expansion, and land water storage. We use observational data for each of the major components of global sea level and a robust adaptive Metropolis-Hastings Bayesian statistical approach to calibrate the model. The sea-level ensemble is described in greater detail in ref. 45. The projections of global mean sea-level (GMSL) change that result from our ensemble of CO2 emissions and temperatures agree well with the center and range of the SSP-RCP scenarios presented in AR6 (Supplementary Fig. 4). Specifically, our GMSL ensemble is centered within the “likely” ranges of SSP2–4.5, SSP3–7.0, and SSP5–8.5 until 2100, and after 2100 within the likely ranges of SSP3–7.0 and SSP5–8.5. The somewhat higher positioning of our ensemble relative to the given SSP-RCP ranges toward the end of the 21st century is attributable to the representation of Antarctic ice sheet sea-level contributions tipping point in the MimiBRICK model. Thus, the tendency of our ensemble towards the SSP5–8.5 “low confidence” range in 2100 and beyond is expected.

We downscale the global sea-level components to their effects on local sea-level change using a set of sea-level fingerprints on a 1° global grid56. These fingerprints have been previously validated, including an analysis of the uncertainties in the sets of geospatial fingerprints associated with each major contributor to global sea-level change56. The magnitudes of the uncertainties for end-of-century (2081–2100) sea-level change are largest near the largest land ice melt contributors (Greenland and West Antarctica). However, all uncertainties are much smaller in comparison to the uncertainties in GMSL itself56 and extreme sea levels that are more tightly associated with coastal risks57. Due to the probabilistic nature of our greenhouse gas emissions emulator, one-to-one comparisons to specific SSP-RCP scenarios are not possible. Our ensemble median is roughly in line with middle/middle-high scenarios among IPCC AR6, namely SSP2–4.5 and SSP3–7.044,45. Spatially, our median sea-level projections are comparable to local sea-level change under SSP3–7.0 given in the IPCC AR644 (see Supplementary Fig. 5 as compared to Fig. 9.28 of ref. 44).

We account for non-climatic factors, including glacial isostatic adjustment, tectonics, and subsidence, in our local sea-level change projections58. As our study is focused on climatic effects on local sea level and its coastal impacts at different temperature thresholds, we do not address the issue of uncertainty in these non-climatic factors affecting local sea-level change. However, we acknowledge the importance of these uncertainties, as they can lead to potentially large differences in future local mean sea level59. We use extreme sea level exposure data from the Global Tide and Surge Reanalysis (GTSR) database60. Given the sizable uncertainties surrounding future extreme sea levels, we performed a supplemental set of simulations to characterize how structural uncertainty in extreme sea levels affects uncertainty in coastal impacts. We compare our main results (using GTSR data) to similar simulations that use the older DINAS-COAST extreme sea level data set. The resulting adaptation costs using GTSR are only slightly higher than when using DINAS-COAST (Supplementary Fig. 6), suggesting that our results are not overly sensitive to these uncertainties. These simulations also serve to bound the range of likely impacts on coastal adaptation costs stemming from uncertainty in the local sea level fingerprints.

Temperature thresholds

Our overall probabilistic ensemble of 100,000 simulations (from which our analysis ensemble of 5000 subsamples are drawn) spans well the range of “very likely” global warming levels throughout the twenty-first century (per the IPCC definition; Supplementary Fig. 3). Specifically, our ensemble 90% range overlaps considerably with the SSP-RCP projection ranges from AR6, in particular SSP2–4.5 in the center, and SSP1–2.6 and SSP3–7.0 in the tails of the distribution (see, e.g., Table SPM.1 and Summary for Policymakers Box B.1.1). While SSP1–1.9 is not represented in the climate and sea-level rise simulations used here, we note that the center and high end of warming in that scenario is still within the range of warming in our ensembles due to the broad sampling of parametric uncertainty in our Bayesian calibration.

We use four temperature bins to represent potential future temperature thresholds for warming in the year 2100, relative to pre-industrial: warming no greater than 1.5 °C, a “2 °C warming world” (warming between 1.5 and 2.5 °C), a 3 °C warming world, and a world with warming greater than 3.5 °C. These temperature thresholds were chosen to balance consistency with previous work15,21 against adequate sample sizes within each threshold bin. We take the pre-industrial reference period as 1850–1900 for consistency with the IPCC definitions. These warming thresholds all have suitably large sample sizes, out of the 5000 total simulations sampled here (Table 1). We repeat our analysis with equal-sized samples for all temperature thresholds and with a smaller (4000 SOW) overall ensemble to affirm that our results are not sensitive to the sample sizes used (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 2).

Coastal impacts and adaptation model

We use the downscaled local sea-level rise as input to the MimiCIAM coastal impacts and adaptation model10. MimiCIAM is an open source version of the Coastal Impacts and Adaptation Model (CIAM7) that has been updated for use in the Mimi coupled modeling framework48. For each of the 12,148 coastal segments of the Database for Impact and Vulnerability Analysis (DIVA61), MimiCIAM computes optimal (least-cost) adaptation decisions and the associated costs and damages. The model does this by considering costs for a range of levels of seawall protection and proactive retreat, or no-action, for each segment. An adaptation option consists of a combination of a strategy (protect or relocate) and level (1-, 10-, 100-, 1000-, or 10,000-year return level). For each adaptation option (including no-action), MimiCIAM computes the decision that minimizes the NPV of expected cost over a ~50-year decision horizon.

MimiCIAM assumes that decision-makers have perfect foresight of future local sea-level rise during this 50-year decision horizon. This type of “perfect foresight assumption” is typical of similar large-scale coastal impacts models (e.g., refs. 2,25,62) and the 50-year time horizon coincides approximately with the timescale on which the sea-level projections under the SSP-RCP scenarios start to significantly diverge44. We note that this model structure, and that of other similar adaptation models, also assumes that the economically-optimal adaptation decision can be/is known, and is implemented without delay. This is, of course, a necessary but stylized assumption that does not reflect the reality that even if optimal adaptation strategies were known, they would be unlikely to occur in practice due to numerous physical, psychological, and organizational barriers to widespread and timely use of (e.g.) managed retreat63. Another important limitation is that large-scale adaptation models such as MimiCIAM do not capture on-the-ground risk perceptions and responses that are taken in light of localized programs, such as the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program64. Additionally, owing to the lack of globally complete and consistent data for current adaptation measures, MimiCIAM implements a model “spin-up” step in which all segments start from an optimal (cost-minimizing) state of initial adaptation. These are optimistic assumptions but can serve as a lower bound on real-world costs and damages incurred by coastal areas.

Total costs are the sum of five categories of costs/losses: wetland loss, retreat/relocation costs, inundation, flood losses of property and life, and construction and maintenance costs associated with seawall protection. We give a brief description of each of these five individual damage components here, but they have been described in much greater detail in other references dedicated to the (Mimi)CIAM model structure7,10. MimiCIAM and our carbon emissions emulator do not explicitly account for the costs associated with mitigation. Our model chain does not prescribe costs associated with reducing emissions or changing energy usage.

Wetland losses are assumed to be quadratic with sea-level rise if coastal segments do not adapt or they relocate. If segments build seawall protection, then MimiCIAM assumes that all wetland area eventually succumbs to sea-level rise due to coastal squeeze. Relocation costs are a function of the amount of mobile/immobile capital and population within each coastal segment. MimiCIAM assumes that one-fourth of capital is mobile and that any relocated population and assets remain within the borders of their respective coastal segments. Inundation costs due to the loss of land unprotected against rising local mean sea level assumes that any mobile capital is reactively relocated upon inundation. Inundation costs are also a function of land value, accounting for potential depreciation over time. Flood losses are computed as the expected damage over the probability distribution for extreme levels exceeding the local level of coastal protection (e.g., a seawall built to the height of the 100-year return level). These damages include both damage to property and potential loss of life. Finally, protection costs are based on the assumption of a general seawall adaptation project and reviews of typical dike or seawall construction and labor costs65,66. Protection costs are assumed to be quadratic in seawall height and linear in seawall length, but constant over time. We note that while some authors use a model for seawall costs that is linear in height67,68, those authors also acknowledge that this is an approximation that works well for relatively small changes in seawall height. Since our model must be applied on a global scale, we retain a more general quadratic model for seawall construction cost as a compromise between a linear model and an exponential one69. While seawall protection may not be a viable strategy in every coastal area, (1) those segments may choose other adaptation strategies and (2) these computed costs provide a reasonable estimate of the overall cost and economically-efficient levels of protection needed in these areas.

We run MimiCIAM with a 10-year time step from 2010 to 2150, divided into three adaptation periods (2010–2050, 2060–2100, and 2110–2150). In the first adaptation period, for each segment, nine combinations of return level of adaptation and adaptation strategy (planned relocation or seawall protection) are considered, as well as a no-adaptation option. Based on local mean sea-level change and the exogenous data for local extreme sea level return levels, MimiCIAM computes the net present value (NPV) of expected damages (including costs) for each of the ten adaptation options. Segments are assumed to immediately implement the adaptation strategy with the minimum expected damages. At the start of each subsequent adaptation period (2060 and 2110), segments update the amount of adaptation to match any changes to the prescribed level of protection. For example, if a segment in the first adaptation period pursues protection at the 100-year return level, and the 100-year storm tide return level for this segment is 1 m, then it is assumed that seawall protection of height 1 m is constructed to protect this segment. In the start of the second adaptation period, suppose that local mean sea-level change means that the 100-year return level is now 1.2 m. Then the segment will augment the existing seawall protection by an additional 0.2 m. Similar updates to the level of protection offered by planned relocation are made if a segment chooses that as a cost-minimizing strategy in the first adaptation period.

If a coastal segment pursues planned relocation, then the associated costs are computed based on the amount of affected mobile population and capital stock, and demolition costs. When relocation is implemented in a coastal segment, whether the relocation is proactive or reactive, assets and people are assumed to stay within the boundaries of the given segment and resume full productivity after relocation. This is of course a stylized assumption by Diaz7 in light of the difficulty and limited data to estimate the proportion of migrants who remain in the segment or leave it, and the destinations and costs associated with the outgoing migrants. If coastal migrants relocated out of the segment completely, then there would be additional costs in the near-term for moving assets and people out of the segment. As pointed out by Lincke and Hinkel2, this would be offset by reduced losses in the long-term by removing these assets and people from harm’s way. Additionally, the reduction of assets and people at risk in the coastal zone means that there may be a reduced need for adaptive action in the future, based on a cost-benefit decision-making framework. If a segment does not adapt (sufficiently) and some area within the segment becomes inundated, then reactive relocation is assumed to cost five times the same level of proactive relocation7. This, too, is a stylized assumption that Diaz7 makes in light of the dearth of global data with which to estimate the relative costs of reactive and proactive relocation. However, Lincke and Hinkel2 point out that these costs in CIAM constitute a 1.2–6× GDP per capita range of migration costs per migrant. As shown in that work, these values are in rough agreement with the range of migration costs employed in other studies and technical reports, which range from 2.3× GDP per capita70 to 9.5× GDP per capita71. As noted by Diaz7, sensitivity analyses provides an important option for characterizing the impacts of these substantial uncertainties on coastal adaptation model output. Indeed, previous work has found that socioeconomic model parameters are influential in coastal impact projections, largely due to the effect of the inherently sizable uncertainties10.

Within MimiCIAM, local capital stocks are assumed to be uniformly distributed across an individual coastal segment. The value of stocks is assumed to be proportional to population density and GDP per capita within the segment, which accommodates the potential for changes in production from changes in population, productivity, or both. MimiCIAM requires exogenous forcing data for socioeconomic conditions, including GDP and population change. We use the SSP scenarios to provide these conditions12, which provides some flexibility for users to examine how changing underlying socioeconomic assumptions affects projected coastal impacts. Additionally, even though population within a given coastal segment in MimiCIAM is assumed to be uniformly distributed, the model includes an adjustment to reflect relatively higher incomes in urban coastal areas as compared to inland areas7. Further details on the MimiCIAM decision-making structure and overall model structure are available in refs. 7,10. We present results aggregated globally (for all coastal regions) as well as aggregated for coastal segments within seven regions, as defined by the World Bank72: (a) East Asia and Pacific, (b) Europe and Central Asia, (c) Latin America and the Caribbean, (d) Middle East and North Africa, (e) North America, (f) South Asia, and (g) Sub-Saharan Africa. The costs presented here are the net present value (NPV) of total adaptation costs and losses, aggregated over the 2150 time horizon. The NPV is calculated as the total discounted optimal (least-cost) adaptation costs/losses as determined by MimiCIAM, assuming that each coastal segment immediately pursues the decision that minimizes the NPV of total adaptation costs. We use a 4% constant discount rate, which is an economic tool to compare present-day costs with future benefits. Discounting accounts for the facts that (1) people generally behave with preference for near-term benefits relative to long-term future benefits and (2) money today could be invested and worth more in the future73. As a simple example in the context of MimiCIAM, future benefits one year from today valued at $1.04 or more would justify spending $1 today on adaptive action that yields those benefits (in terms of reduced losses). All monetary units are in terms of 2010 United States dollars ($), unless otherwise explicitly stated.

Code availability

All code required to run the simulations and generate the results shown here are available from GitHub.

References

Calvin, K. et al. IPCC, 2023: Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Core Writing Team, H. Lee, J. Romero). (IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023). https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/, https://doi.org/10.59327/IPCC/AR6-9789291691647.

Lincke, D. & Hinkel, J. Coastal migration due to 21st century sea-level rise. Earths Future 9, e2020EF001965 (2021).

Desmet, K. et al. Evaluating the economic cost of coastal flooding. Am. Econ. J. Macroecon. 13, 444–486 (2021).

Rashid, M. M., Wahl, T., Chambers, D. P., Calafat, F. M. & Sweet, W. V. An extreme sea level indicator for the contiguous United States coastline. Sci. Data 6, 1–14 (2019).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Weather and Climate Extreme Events in a Changing Climate. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. pp 1513–1766. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.013 (2021).

Hoegh-Guldberg, O. et al. The human imperative of stabilizing global climate change at 1.5°C. Science 365, eaaw6974 (2019).

Diaz, D. B. Estimating global damages from sea level rise with the Coastal Impact and Adaptation Model (CIAM). Clim. Change 137, 143–156 (2016).

Lincke, D. & Hinkel, J. Economically robust protection against 21st century sea-level rise. Glob. Environ. Change 51, 67–73 (2018).

Tiggeloven, T. et al. Global-scale benefit–cost analysis of coastal flood adaptation to different flood risk drivers using structural measures. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 1025–1044 (2020).

Wong, T. E. et al. Sea level and socioeconomic uncertainty drives high-end coastal adaptation costs. Earths Future 10, e2022EF003061 (2022).

Moss, R. H. et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010).

Riahi, K. et al. The Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and their energy, land use, and greenhouse gas emissions implications: an overview. Glob. Environ. Change 42, 153–168 (2017).

Rhodes, C. J. The 2015 Paris climate change conference: COP21. Sci. Prog. 99, 97–104 (2016).

Lüthi, S. et al. Rapid increase in the risk of heat-related mortality. Nat. Commun. 14, 4894 (2023).

Jevrejeva, S., Jackson, L. P., Grinsted, A., Lincke, D. & Marzeion, B. Flood damage costs under the sea level rise with warming of 1.5 °C and 2 °C. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074014 (2018).

Ehlert, D. & Zickfeld, K. What determines the warming commitment after cessation of CO2 emissions? Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 015002 (2017).

Hare, B. & Meinshausen, M. How much warming are we committed to and how much can be avoided? Clim. Change 75, 111–149 (2006).

Zickfeld, K. et al. Long-term climate change commitment and reversibility: an EMIC intercomparison. J. Clim. 26, 5782–5809 (2013).

Levermann, A. et al. The multimillennial sea-level commitment of global warming. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13745–13750 (2013).

Dvorak, M. T. et al. Estimating the timing of geophysical commitment to 1.5 and 2.0 °C of global warming. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 547–552 (2022).

Tebaldi, C. et al. Extreme sea levels at different global warming levels. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 746–751 (2021).

Mengel, M., Nauels, A., Rogelj, J. & Schleussner, C. F. Committed sea-level rise under the Paris Agreement and the legacy of delayed mitigation action. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–10 (2018).

Nauels, A. et al. Attributing long-term sea-level rise to Paris Agreement emission pledges. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA TBD 116, 23487–23492 (2019).

Portner, H.-O., Roberts, D., Trisos, C. & Simpson, N. Summary for Policymakers: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009325844.001 (2022).

Anthoff, D., Nicholls, R. J. & Tol, R. S. J. The economic impact of substantial sea-level rise. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 15, 321–335 (2010).

Brown, S. et al. Quantifying land and people exposed to sea-level rise with no mitigation and 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C rise in global temperatures to year 2300. Earths Future 6, 583–600 (2018).

Hartin, C. et al. Advancing the estimation of future climate impacts within the United States. Earth Syst. Dyn. 14, 1015–1037 (2023).

Nauels, A., Meinshausen, M., Mengel, M., Lorbacher, K. & Wigley, T. M. L. Synthesizing long-term sea level rise projections—the MAGICC sea level model v2.0. Geosci. Model Dev. https://doi.org/10.5194/gmd-10-2495-2017 (2017).

Wong, T. E., Bakker, A. M. R. & Keller, K. Impacts of Antarctic fast dynamics on sea-level projections and coastal flood defense. Clim. Change 144, 347–364 (2017).

IPCC. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 3−32 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.001 (2021).

Azar, C. & Sterner, T. Discounting and distributional considerations in the context of global warming. Ecol. Econ. 19, 169–184 (1996).

Dennig, F., Budolfson, M. B., Fleurbaey, M., Siebert, A. & Socolow, R. H. Inequality, climate impacts on the future poor, and carbon prices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 15827–15832 (2015).

Nicholls, R. J. et al. Sea-level rise and its possible impacts given a ‘beyond 4 °C world’ in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 369, 161–181 (2011).

Archer, D. & Brovkin, V. The millennial atmospheric lifetime of anthropogenic CO2. Clim. Change 90, 283–297 (2008).

Clark, P. U. et al. Consequences of twenty-first-century policy for multi-millennial climate and sea-level change. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 360–369 (2016).

Lenton, T. M. et al. Millennial timescale carbon cycle and climate change in an efficient Earth system model. Clim. Dyn. 26, 687–711 (2006).

Plattner, G.-K. et al. Long-term climate commitments projected with climate–carbon cycle models. J. Clim. 21, 2721–2751 (2008).

Clark, P. U. et al. Sea-level commitment as a gauge for climate policy. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 653–655 (2018).

Mengel, M. et al. Future sea level rise constrained by observations and long-term commitment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 2597–2602 (2016).

Lowry, D. P., Krapp, M., Golledge, N. R. & Alevropoulos-Borrill, A. The influence of emissions scenarios on future Antarctic ice loss is unlikely to emerge this century. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 1–14 (2021).

Haasnoot, M. et al. Long-term sea-level rise necessitates a commitment to adaptation: a first order assessment. Clim. Risk Manag. 34, 100355 (2021).

Haasnoot, M. et al. Adaptation to uncertain sea-level rise; how uncertainty in Antarctic mass-loss impacts the coastal adaptation strategy of the Netherlands. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 034007 (2020).

Hinkel, J. et al. Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3292–3297 (2014).

Fox-Kemper, B. et al. Ocean, Cryosphere and Sea Level Change. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. pp 1211–1362 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.011 (2021).

Darnell, C., Rennels, L., Errickson, F., Wong, T. & Srikrishnan, V. Impacts of emissions uncertainty on Antarctic instability and sea-level rise. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/j47ts (2024).

Urban, N. M. & Keller, K. Probabilistic hindcasts and projections of the coupled climate, carbon cycle and Atlantic meridional overturning circulation system: a Bayesian fusion of century-scale observations with a simple model. Tellus A 62, 737–750 (2010).

Wong, T. E. et al. MimiBRICK.jl: a Julia package for the BRICK model for sea-level change in the Mimi integrated modeling framework. J. Open Source Softw. 7, 4556 (2022).

Anthoff, D., Plevin, R. J., Kingdon, C. & Rennels, L. Mimi Framework. Mimi: An Integrated Assessment Modeling Framework. https://www.mimiframework.org/ (2022).

Moore, J. C., Grinsted, A., Zwinger, T. & Jevrejeva, S. Semiempirical and process-based global sea level projections. Rev. Geophys. 51, 484–522 (2013).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. Achievements and needs for the climate change scenario framework. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 1074–1084 (2020).

Anderson, K. & Peters, G. The trouble with negative emissions. Science 354, 182–183 (2016).

Kriegler, E. et al. Pathways limiting warming to 1.5 °C: a tale of turning around in no time? Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376, 20160457 (2018).

Smith, P. et al. Biophysical and economic limits to negative CO2 emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 42–50 (2016).

Vaughan, N. E. & Gough, C. Expert assessment concludes negative emissions scenarios may not deliver. Environ. Res. Lett. 11, 095003 (2016).

Morgan, M. G. & Keith, D. W. Improving the way we think about projecting future energy use and emissions of carbon dioxide. Clim. Change 90, 189–215 (2008).

Slangen, A. B. A. et al. Projecting twenty-first century regional sea-level changes. Clim. Change 124, 317–332 (2014).

Wahl, T. et al. Understanding extreme sea levels for broad-scale coastal impact and adaptation analysis. Nat. Commun. 8, 16075 (2017).

Kopp, R. E. et al. Probabilistic 21st and 22nd century sea-level projections at a global network of tide-gauge sites. Earths Future 2, 383–406 (2014).

Slangen, A. B. A. et al. The evolution of 21st century sea-level projections from IPCC AR5 to AR6 and beyond. Camb. Prisms Coast. Future 1, e7 (2023).

Muis, S., Verlaan, M., Winsemius, H. C., Aerts, J. C. J. H. & Ward, P. J. A global reanalysis of storm surges and extreme sea levels. Nat. Commun. 7, 11969 (2016).

Vafeidis, A. T. et al. A new global coastal database for impact and vulnerability analysis to sea-level rise. J. Coast. Res. 24, 917–924 (2008).

Depsky, N. et al. DSCIM-Coastal v1.0: An Open-Source Modeling Platform for Global Impacts of Sea Level Rise. EGUsphere https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-2022-198 (2022).

Siders, A. R. Managed retreat in the United States. One Earth 1, 216–225 (2019).

Elliott, R. Scarier than another storm’: values at risk in the mapping and insuring of US floodplains. Br. J. Sociol. 70, 1067–1090 (2019).

Hillen, M. M. et al. Coastal defence cost estimates: case study of the Netherlands, New Orleans and Vietnam. Commun. Hydraul. Geotech. Eng. No 2010-01 (2010).

World Bank. International Comparison Program (ICP) 2017. (2017).

Jonkman, S. N., Hillen, M. M., Nicholls, R. J., Kanning, W. & Ledden, M. Costs of adapting coastal defences to sea-level rise—new estimates and their implications. J. Coast. Res. 29, 1212–1226 (2013).

van Dantzig, D. Economic decision problems for flood prevention. Econometrica 24, 276–287 (1956).

Eijgenraam, C., Brekelmans, R., Hertog, D. D. & Roos, K. Flood Prevention by Optimal Dike Heightening. Feweb.Uvt.Nl 1–17 (2012).

Regeneris Consulting. Coastal Pathfinder Evaluation: An Assessment of the Five Largest Pathfinder Projects. Rep. Prep. Defra (2011).

State of Louisiana. National Disaster Resilience Competition Phase II Application. http://www.coastalresettlement.org/uploads/7/2/9/7/72979713/ndrc_pii_final_eximg-w_highlights.pdf (2015).

World Bank Country and Lending Groups—World Bank Data Help Desk. https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups.

Prest, B. Discounting 101. Resources for the Future https://www.rff.org/publications/explainers/discounting-101/ (2022).

Acknowledgements

We thank Frank Errickson, Radley Powers, and Lisa Rennels for fruitful conversations. This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Award No. DMS-2213432. V.S. and C.D. were supported by the MultiSector Dynamics program area of the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research as part of the multi-program, collaborative Integrated Coastal Modeling (ICoM) project. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.D. and C.D. coded and ran the initial analysis. S.D. contributed to the final analysis and contributed to writing the final paper draft. K.F. assisted in data collection and running the initial analysis, and contributed to writing the final paper draft. V.S. and T.E.W. supervised the research and contributed to writing the final paper draft. T.E.W. conceptualized the research, wrote the initial paper draft, led the final analysis, and contributed to writing the final paper draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, T.E., Dake, S., Feke, K. et al. Coastal adaptation and damage costs at different global warming thresholds. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 35 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00089-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00089-0