Abstract

Super Typhoon Doksuri caused severe damage to Fujian Province, a core region of subtropical forest distribution along the southeastern coast of China. This study utilized MODIS reflectance data and the Google Earth Engine platform to quantify the extent of forest damage and post-typhoon recovery. Results showed that approximately 38.93% of forests were affected to varying degrees. After controlling for seasonal and interannual variability, NDVI during the typhoon period declined by 0.0241 compared to the same period in 2022 and by 0.0282 compared to the multi-year average. Considering the spatial heterogeneity of wind effects, regression models combined with Shapley Additive Explanations were used to analyze the regulatory roles of topography, precipitation, runoff, and forest type. The results indicate that elevation and runoff are key factors influencing damage severity, with high-elevation and low-runoff areas suffering the most. This remote sensing-based framework aids forest vulnerability assessment and supports disaster management and ecological conservation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Super-typhoons/hurricanes are among the most severe natural disasters in coastal regions globally, due to their extreme wind speeds and heavy rainfall, causing significant impacts on forest ecosystems and socioeconomic systems1,2,3. In recent years, with global climate warming, typhoon intensity has significantly increased in the Northwest Pacific region, leading to more severe disturbances to forest ecosystems2,4,5,6,7. Fujian Province, as a high-frequency typhoon landfall area along Southeast China’s coast, due to its unique geographical location and extensive forest coverage, has become a disaster-prone region for typhoon events. Typhoon Doksuri (International designation: 2305), the fifth named storm of the 2023 Pacific typhoon season, made landfall in Fujian with wind speeds reaching 50 m/s, making it one of the strongest typhoons to hit the province in recent years and causing significant impacts on local forests.

The direct impacts of super typhoons on forests include various forms of physical damage such as tree uprooting, bole/stem breakage, branch breakage, canopy damage, and defoliation. These are often accompanied by secondary disasters like soil erosion, pest outbreaks, and flooding. These combined effects disrupt forest carbon cycling, ecosystem services, and overall forest health8,9,10. Existing studies mainly focus on several aspects: first, field measurements based on established forest inventory plots to assess typhoon damage, mainly addressing the direct physical impacts such as tree tipping, branch loss, and canopy damage8,11; second, direct quantitative evaluations of typhoon damage, such as canopy destruction area and carbon loss estimates12,13,14,15; and third, analyses of forest resilience, including the effects of species composition, tree age, and density16,17,18. These studies still have limitations: firstly, most research focuses on small-sample field observations or single forest types, with only a few studies attempting to model the effects across entire landscapes. Secondly, typhoon-induced forest damage patterns are influenced not only by factors such as wind speed and forest structure but also by environmental characteristics like topography and precipitation, as well as the combined effects of various drivers19,20,21,22. However, this spatial heterogeneity and its driving mechanisms have not been systematically or comprehensively quantified23. Moreover, ground-based assessments of typhoon impacts are limited by time and spatial coverage, making it challenging to comprehensively capture the extent and intensity of disturbances on a large scale.

With the rapid advancement of remote sensing technology, large-scale dynamic monitoring of typhoon disasters and their spatial variability has become possible24,25,26,27. For instance, time-series analysis of vegetation indices can be used to assess post-disaster recovery dynamics, while optical imagery provides a basis for studying the spatial distribution of forest impacts at the landscape scale28,29,30. However, most existing studies remain focused on quantifying forest damage using different remote sensing vegetation indices, although this serves as a foundation for subsequent research31. There is still a lack of in-depth exploration of the mechanisms influencing the spatial distribution of typhoon damage to forests30,32,33. Therefore, further research is needed to quantify disaster dynamics and analyze their environmental driving mechanisms.

This study investigates the impact of Typhoon Doksuri (2023) by integrating multi-source remote sensing data using the Google Earth Engine (GEE) platform, with a focus on MODIS reflectance data due to its high temporal resolution and broad spatial coverage, combined with topography, land cover, and precipitation datasets. It quantifies damage to subtropical forests in China and analyzes the heterogeneity of its driving factors. The findings provide scientific evidence for the dynamic assessment of typhoon-induced disasters and ecological restoration, offering theoretical support for the protection and recovery strategies of subtropical coastal forests in the context of climate change.

Results

Forest loss in Fujian due to typhoon Doksuri

According to statistical data, within one month after the passage of Typhoon Doksuri, the total forest area affected in Fujian Province accounted for 38.93% of the province’s total forest coverage. Based on the extent of damage, the net canopy loss caused by the typhoon was estimated at 2.36%. As shown in the spatial distribution of canopy loss (Fig. 1), the most severe and concentrated damage occurred near the typhoon’s landfall point. In other areas, although wind speeds along the typhoon’s path gradually weakened from the coast to the inland, neither the affected forest area nor the degree of damage showed a significant decrease accordingly. The impacted areas exhibited a fragmented distribution pattern, with significant canopy loss observed in both coastal and inland regions. Forest patches located at the forest edges were especially vulnerable.

Figure 1 further illustrates the changes in forest loss one, two, and three months after the typhoon. Overall, the condition of the forests showed a trend of gradual recovery. The proportion of healthy forests increased from 61.07% in the first month to 68.12% in the second month, and further rose to 82.11% by the third month. Notably, the rate of recovery was faster in the third month compared to the second. In addition, the proportion of damaged forest areas (including negligible, minor, moderate, and severe damage) steadily declined over time, and by the third month, the area classified as severely damaged had dropped to just 0.1% of the province’s total forest area.

At the city level, the areas most significantly affected by the typhoon were Putian, Quanzhou, and Xiamen, all located near the typhoon’s landfall point. Within the first month following the typhoon, the proportions of forest damage in these cities were 61.03% (with healthy forests accounting for 38.97%), 48.25% (healthy forests: 51.75%), and 53.25% (healthy forests: 46.75%), respectively. In terms of damage severity, Longyan, Sanming, and Xiamen ranked highest in the proportion of forests with moderate to severe damage. This ranking differs from that based on total damaged area, indicating a degree of spatial heterogeneity in both the extent and structure of forest damage across cities (Table 1).

Post-typhoon forest greenness dynamics in Fujian

The MODIS-NDVI analysis quantifies the temporal impact of Typhoon Doksuri on forests in Fujian Province (as shown in Fig. 2). During the 2023 typhoon period, the NDVI for Fujian Province displayed a sharp decline in forest canopy greenness (red line in Fig. 2b), noticeably lower than the average NDVI level since 2010 (black line in Fig. 2b). Specifically, the average NDVI in September 2023 was 4.73% lower than the same month in 2022 and fell below the 4.30% average NDVI level for September since 2010. Despite the severe short-term damage caused by the typhoon, NDVI data show that forests in Fujian began a rapid recovery within three months post-typhoon, with noticeable short-term gains in greenness. However, the overall greenness levels did not fully recover to the normal range since 2017 (green line in Fig. 2a). Further 2024 NDVI data indicate that, although an initial rapid recovery of forest greenness occurred after the typhoon, the long-term recovery of forests post-typhoon remains significantly delayed, with NDVI values even reaching the lowest greenness level since 2017 (blue line in the Fig. 2a). Notably, since 2017, Fujian Province has ceased commercial logging in state-owned forests and increased the ban on logging to 100%, significantly enhancing the overall greenness level of its forests. Therefore, using the greenness levels since 2017 as a baseline provides a more accurate reference for assessing forest greenness changes and recovery after typhoon disturbances.

Further time-based DiD analysis revealed a notable decline in NDVI from August to October 2023 compared to both the corresponding period in 2022 and the multi-year average from 2017 to 2022 (as shown in Fig. 3). Specifically, NDVI during the typhoon-affected period decreased by 0.0241 relative to 2022, and by 0.0282 relative to the multi-year average. This decline, having controlled for seasonal and interannual variations, confirms the disruptive impact of Typhoon Doksuri on the canopy greenness of subtropical forests in Fujian.

a Shows the monthly NDVI changes in 2023 (red solid line) compared to those in 2022 (blue solid line). b compares the 2023 NDVI (red solid line) with the multi-year average from 2017 to 2022 (blue solid line). The red dashed line represents the NDVI trend in 2023 fitted using the DiD model, while the blue dashed line represents the fitted trend for the control group. The gray shaded area indicates the net NDVI loss from August to October 2023.

Impact of topography on forest loss

In the previous results, we showed that wind speed alone does not fully determine the severity of forest damage, and that there are notable differences in damage extent and structural characteristics across different cities. We believe that these patterns are likely influenced by intrinsic characteristics of terrestrial forests, such as topographic variation, forest types, and tree height. These factors interact with typhoon disturbances in complex ways, collectively shaping the forest’s resistance and recovery potential.

Figure 4 presents the relationship between forest loss and various topographic features, further exploring this hypothesis. Specifically, elevation shows a significant effect on forest loss: as elevation increases, the extent of forest damage gradually becomes more severe, with a marked increase in loss observed above 1000 m. In contrast, slope exerts a relatively smaller influence. Violin plots do not reveal a clear pattern, and the distribution of forest loss does not show significant differences across slope classes. However, slightly higher median losses are observed for slopes between 10° and 20° and above 40°. Regarding slope aspect, although no consistent trend is apparent, median forest loss is slightly higher on windward slopes compared to leeward slopes, suggesting greater exposure and damage on windward faces. Simple linear regression analysis shows a statistically significant positive correlation between forest loss and elevation (p < 0.001), with elevation alone explaining 5.9% of the variance in forest disturbance.

Impact of precipitation and runoff on forest loss

Figure 5 illustrates the impact of cumulative precipitation and runoff on forest loss. For precipitation, the severity of forest loss increases with cumulative rainfall up to 350 mm, but becomes lighter when cumulative rainfall reaches 350–400 mm. In contrast to precipitation, runoff shows a negative correlation with forest loss. Higher runoff values are associated with a decreasing trend in forest loss severity. Particularly in areas with greater runoff, forest loss severity is significantly reduced. Simple linear regression analysis shows a statistically significant negative correlation with runoff (p < 0.001), with runoff explaining 1.7% of the variance in forest disturbance.

Impact of forest conditions on forest loss

Figure 6 shows the impact of different forest types and canopy cover on forest loss. The results indicate that deciduous broadleaf forests experience the most severe loss, with a significantly higher level of damage compared to evergreen broadleaf forests and evergreen coniferous forests, which are the predominant forest types in Fujian Province. Additionally, there is no expected negative correlation between canopy cover and forest loss. However, when canopy cover is below 20%, forest loss is the most severe, whereas when canopy cover exceeds 40%, the severity of forest loss significantly decreases.

Impact of typhoon proximity and wind speed on Forest Loss

Figure 7 indicates that forest loss is most severe in areas located within 40 km and between 80 km and 120 km from the typhoon track, as well as within 80 km and between 160 km and 240 km from the landfall point. In addition, maximum wind speed shows a clear positive relationship with forest loss under certain conditions. When wind speeds exceed 20 m/s, forest loss intensifies with increasing wind velocity, and particularly above 40 m/s, the upper quartile of the violin plots surpasses 0.2, indicating extremely high losses in some regions. Notably, even at wind speeds below 20 m/s, the median forest loss remains relatively high, which may be related to the spatial distribution of forests or their wind resistance characteristics.

Analysis of variable importance in damage detection

In addition, we further employed a multiple linear regression model to systematically evaluate the explanatory power and significance of various factors affecting forest loss. Before interpreting the regression results, we first assessed the potential issue of multicollinearity among the explanatory variables. By calculating the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF), we found that all variables had VIF values below the commonly used threshold of 5 (Fig. 8), indicating no moderate or severe multicollinearity in the model. Therefore, the regression coefficients are stable and interpretable.

As shown in Table 2, the results of the multiple linear regression indicate that most factors in the model have a significant impact on variations in forest loss caused by the typhoon (all p < 0.001), except for forest type, which was excluded from the regression framework as it is a categorical variable. Among these factors, elevation exhibits the highest standardized coefficient (SC = 0.184), making it the most important variable in explaining forest loss. Cumulative runoff shows a significant negative correlation with forest loss (SC = −0.114), reflecting its critical role as a moderating factor. Maximum wind speed (SC = 0.102), cumulative precipitation (SC = 0.080), windwardness (SC = 0.037), and slope (SC = −0.034) also contribute to forest loss, though their effects are relatively weaker. Collectively, these factors account for 38.1% of the variance in forest loss (R² = 0.391).

Further SHAP analysis results were consistent with the findings of the multiple regression analysis (as shown in Fig. 9), with elevation having the highest median Shapley value, clearly indicating that elevation is one of the most important contributing variables in predicting forest loss. Cumulative runoff and cumulative precipitation ranked as the second and third most important variables, respectively.

a Shows the importance ranking of all variables. b–d present the scatter plots of SHAP values and their dependence on the three most important variables identified in (a): b the dependence relationship between elevation and its SHAP values, c the dependence relationship between cumulative runoff and its SHAP values, and d the dependence relationship between cumulative precipitation and its SHAP values.

The SHAP dependence plots further revealed the nonlinear influence of key variables on forest loss prediction. Specifically, the SHAP values for elevation showed a significant upward trend with increasing elevation, indicating that the model predicts a higher risk of forest loss in high-elevation areas. Similarly, the impact of runoff on SHAP values was evident, particularly in low-runoff regions where SHAP values were higher, reflecting the model’s prediction of higher forest loss risk in these areas. For precipitation, SHAP values were influenced by interactions with the distance from the typhoon landfall point. High precipitation areas near the typhoon landfall point exhibited higher SHAP values, suggesting an increased risk of forest loss in these regions according to the model predictions.

Sentinel-2 cross-validation results

To cross-validate the MODIS ΔNDVI and to examine the influence of spatial resolution on forest damage assessment, we conducted a comparative analysis using Sentinel-2-derived ΔNDVI (Fig. 10). The results show that the ΔNDVI calculated from MODIS imagery on August 13, 2023, had a mean of 0.095 and a standard deviation of 0.132. In contrast, the ΔNDVI derived from Sentinel-2 imagery acquired 5, 10, and 15 days after the typhoon (August 2, 7, and 12, respectively) had means of 0.090, 0.082, and 0.101, and standard deviations of 0.115, 0.091, and 0.116, respectively. After gap-filling and compositing the three Sentinel-2 ΔNDVI (Sentinel_composite), the mean and standard deviation were 0.090 and 0.099, respectively.

At the spatial scale, when Sentinel-2 ΔNDVI was aggregated to MODIS resolution, pixel-wise ΔNDVI showed significant positive correlations with the MODIS results. The correlation coefficients for the imagery acquired 5, 10, and 15 days after the typhoon were 0.74, 0.76, and 0.74, respectively (p < 0.01). These findings indicate that forest disturbance patterns caused by the typhoon can be consistently identified using both high-resolution Sentinel-2 and MODIS data, thereby validating the reliability of the MODIS results and highlighting the robustness of forest damage assessments across spatial scales.

Discussion

This study systematically assessed the forest loss and recovery processes in Fujian Province following Typhoon Doksuri. By integrating remote sensing observations, statistical analysis, and machine learning methods, it revealed the short-term disturbances caused by extreme storms and the heterogeneous responses of subtropical forest ecosystems. Results showed that within one month after the typhoon, approximately 38.93% of forest areas experienced varying degrees of disturbance, with a net canopy loss of 2.36%. After controlling for seasonal and interannual variability, NDVI during the typhoon period declined by 0.0241 compared to the same period in 2022 and by 0.0282 relative to the multi-year average. The most severely affected regions were concentrated around the landfall areas, including Putian, Quanzhou, and Xiamen. Despite the evident damage, the forests exhibited strong resilience, with significant greenness recovery observed within three months. The proportion of healthy forests increased from 61.07% in the first month to 82.11% in the third month, and severely damaged areas decreased significantly, indicating a clear trend of ecological recovery.

The spatial heterogeneity of forest loss was driven by multiple environmental factors. Regression and SHAP analysis identified elevation as the most critical factor influencing forest loss, with areas above 1000 m particularly affected. This may be due to stronger winds and lower vegetation stability in high-altitude regions34. Runoff showed a negative correlation with forest loss, suggesting that areas with higher runoff faced a lower risk of damage—likely due to better soil moisture conditions and more stable hydrological environments that support post-typhoon vegetation regeneration. This finding contrasts with some studies that argue high runoff intensifies erosion and destruction, highlighting the complexity of hydrological processes35. It also suggests that local soil properties, vegetation types, and topography may modulate the effects of runoff. Precipitation did not exhibit a consistent positive or negative correlation with forest loss; however, its interaction with the typhoon path caused significant damage in landfall regions, indicating that the spatial distribution and extremity of precipitation also play a critical role in the disturbance process. Moreover, forest type and canopy cover significantly influenced the degree of damage. Deciduous broadleaf forests suffered the most, followed by evergreen coniferous forests, while the widely distributed evergreen broadleaf forests in Fujian were relatively less affected. Forests with lower canopy cover were more susceptible to disturbance, whereas those with higher coverage demonstrated stronger resistance. These results emphasize the importance of considering multiple environmental variables and their interactions when assessing forest loss risk.

Although this study effectively captured forest greenness dynamics using MODIS-NDVI data, NDVI is less sensitive to structural damage such as trunk breakage or treefall. NDVI declined rapidly after the typhoon but returned to multi-year average levels within two months. This quick recovery may reflect the regrowth of partially damaged trees and compensatory growth of understory vegetation36,37. However, despite the rebound in greenness, NDVI time series indicated that forest conditions had not fully returned to pre-disturbance trajectories even one year later—consistent with previous studies suggesting structural and functional recovery after severe damage can take 5–10 years38,39. Additionally, in some regions, NDVI continued to decline in the second month post-typhoon and did not rise significantly until October. This may indicate the effects of secondary disturbances such as pest outbreaks, nutrient loss, or anthropogenic activities like logging23,40,41,42. These observations highlight the high temporal sensitivity of remote sensing and reveal the limitations of relying solely on a single vegetation index to reflect complex ecological responses43.

Meanwhile, the overall greening trend driven by ecological policies may obscure localized forest mortality caused by typhoons44,45. Our findings show that although NDVI in 2023 was lower than in the previous year and below the six-year average, it still exceeded levels observed before 2017. This suggests that forest damage from extreme typhoons may be “diluted” within a broader greening trend, especially when using medium- to low-resolution remote sensing data46. This further underscores the necessity of multi-source and multi-scale observations.

To improve the accuracy and ecological interpretability of typhoon disturbance studies, future research should strengthen the integration of remote sensing and ground-based observations. While remote sensing provides broad coverage and frequent updates, it has limitations in explaining structural damage and ecological processes. In contrast, field observations—though spatially limited and temporally lagged—can offer irreplaceable insights into ecological mechanisms. Currently, our post-disturbance field data remain insufficient. In future work, we will aim to incorporate more data types (e.g., EVI, NBR, which are more sensitive to structural changes) and scales (including ground-based measurements) for comparative analysis, combined with ecological process models to uncover the real impact of localized forest mortality within broader trends.

In conclusion, this study identifies elevation and runoff as key drivers of forest loss during typhoon events in Fujian Province. It underscores the importance of multi-factor coupled analysis and multi-scale data integration in assessing forest disaster impacts. Moving forward, it is essential to build a data-driven predictive framework based on multi-source observations, integrating remote sensing technologies and ecological models to provide scientific support for regional ecological restoration, adaptation strategies, and sustainable forest management in the context of extreme climate events.

Methods

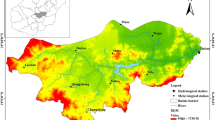

Study area

Fujian Province is situated in the southeastern coastal region of China, extending approximately from 23° 31′ to 28° 18′ N and 115° 50′ to 120° 43′ E. It is bordered by the East China Sea to the east and the Taiwan Strait to the south, positioning it as one of the mainland provinces with the closest proximity to the Pacific Ocean (as shown in Fig. 11). The province exhibits a complex and heterogeneous topography, predominantly characterized by mountainous and hilly terrain, with flatlands primarily confined to coastal areas and river basins. Fujian possesses extensive forest resources, boasting the highest forest coverage rate in China at 65.12%, and supports a diverse array of forest types. Climatically, Fujian falls within the subtropical monsoon climate zone, experiencing hot and humid summers and mild, precipitation-rich winters. According to the 2023 Climate Bulletin of Fujian Province published by China Weather Network (https://fj.weather.com.cn/zxfw/qhgb/07/3797835.shtml), the average annual precipitation ranged from 1600 mm to 1800 mm during the period from 2000 to 2023, and the mean annual temperature ranged between 15 °C and 21 °C. Typhoons constitute a significant climatic feature of Fujian, particularly during the summer and autumn months, exerting profound ecological impacts and posing considerable socio-economic challenges.

The study area is Fujian Province, China. The track of Typhoon Doksuri is shown as the blue line, with variations in wind speed represented by points in different colors. Forest types include evergreen broadleaf (EB), evergreen needleleaf (EN), deciduous broadleaf (DB), shrubland, and wetlands. The typhoon track data were obtained from the Typhoon Network of the China Meteorological Administration (http://typhoon.nmc.cn/web.html), and forest type information was derived from the MODIS Land Cover Type product (MCD12Q1, Version 6.1).

Typhoon Doksuri

The super typhoon Doksuri formed on July 21, 2023, in the northwest Pacific Ocean, reaching its peak intensity on July 25 with a maximum sustained wind speed of 62 m/s. On the morning of July 28 at approximately 9:55 AM, Doksuri made landfall in Jinjiang, Fujian Province, as a strong typhoon, becoming the strongest typhoon to hit mainland China in 2023 and the second strongest typhoon to make landfall in Fujian since 1949. The storm had a wide-reaching impact, affecting five provinces, including Fujian, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, and Guangdong, resulting in approximately 2.95 million people being affected and direct economic losses amounting to 14.95 billion yuan. Particularly in eastern Fujian, local gusts reached levels between 11 and 16, causing severe damage. In Fujian cities such as Quanzhou, Putian, and Fuzhou, five meteorological observation stations recorded historical record-breaking daily rainfall, significantly impacting local ecosystems, infrastructure, and public transportation systems.

Satellite image data

In this study, we employed the MODIS Terra 16-day composite Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) product (MOD13A1 V6.1) to assess the impact of Typhoon Doksuri on forest vegetation in Fujian Province. This product provides vegetation indices at a 500 m spatial resolution and has undergone atmospheric correction and bidirectional reflectance distribution function (BRDF) normalization during generation, along with pixel-level quality assurance (QA) information. In our analysis, pixels were strictly filtered based on the QA mask to exclude clouds, shadows, and low-quality data, retaining only high-quality pixels with atmospheric and BRDF correction for the calculation of ΔNDVI. Taking the landfall date of the typhoon (28 July 2023) as the reference point, we selected the image from 12 July 2023 (the closest cloud-free image prior to landfall) as the pre-event baseline representing forest health conditions, and the image from 13 August 2023 (the earliest available image after landfall) as the post-event impact state of initial vegetation damage. This selection minimizes the influence of seasonal phenological variations on the analysis and allows a more accurate characterization of canopy condition changes before and after landfall. All remote sensing data processing and analysis were conducted on the GEE platform to ensure efficient computation and precise extraction of NDVI time series, thereby quantifying the direct impact of the typhoon on vegetation.

To supplement the MODIS analysis and enable cross-validation, we further employed Sentinel-2 Level-2A surface reflectance imagery (with a temporal resolution of approximately 5 days) to evaluate forest canopy changes. NDVI was calculated using the red band (Band 4, 665 nm) and near-infrared band (Band 8, 842 nm), both with a spatial resolution of 10 m. Due to persistent cloud cover in Fujian before and after the typhoon, the pre-event baseline image was generated by compositing multiple scenes around 12 July 2023, in order to best capture the forest health conditions prior to landfall. To monitor post-typhoon vegetation dynamics and short-term recovery, three images were selected on 2 August, 7 August, and 12 August 2023. Within this time window, we prioritized the least cloud-contaminated scenes, even if partial data gaps remained. All Sentinel-2 images were atmospherically corrected using the Sen2Cor processor and further refined with the s2cloudless algorithm for cloud and shadow masking, ensuring high-quality surface reflectance data for ΔNDVI calculation. With its higher spatial and temporal resolution, Sentinel-2 provides a more detailed depiction of the spatial distribution of typhoon-induced disturbances and offers validation for the MODIS-based results.

Terrain data

Typhoon wind speed is a key factor affecting the extent of forest disturbance, and local topographic conditions such as elevation, slope, and windwardness can significantly influence wind speed after typhoon landfall. The elevation data used in this study were obtained from the Global Multiresolution Terrain Elevation Data 2010 (GMTED2010), released by the United States Geological Survey (USGS), which provides a global Digital Elevation Model (DEM) based on the reference year 2010. The data were acquired using the ‘ee.Terrain.products()‘ function on the GEE platform. Slope and aspect were calculated using the ‘ee.Terrain.slope‘ and ‘ee.Terrain.aspect‘ functions, respectively.

To further characterize the impact of topography on wind speed, we developed a windwardness index, combining aspect with typhoon path direction to quantify the degree to which terrain faces the direction of the typhoon. Assuming maximum wind speed occurs in the direction of the typhoon path, the highest windwardness index is defined as 180 for regions directly facing southeast toward the strongest wind, while regions on the leeward side have an index of 0. This index helps precisely assess how terrain affects typhoon wind speed and its impact on forest damage.

Wind, precipitation, and runoff

This study also examines the impact of typhoon-related precipitation, surface runoff, and wind speed on forest damage. To match the time window used for ΔNDVI detection (from typhoon landfall to post-event: July 28 to August 13, 2023), precipitation and runoff were calculated as cumulative values, and the maximum wind speed was extracted over the same period. All three datasets were obtained from the ERA5-Land Hourly dataset, a climate reanalysis product provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). The dataset has a spatial resolution of 11,132 m and provides hourly land-surface meteorological and hydrological variables, including precipitation, runoff, and surface wind speed, allowing for continuous, long-term regional-scale analysis and modeling. ERA5-Land is generated by re-running the land surface component of the original ERA5 reanalysis, offering high-accuracy and temporally consistent representations of terrestrial hydrological and meteorological variables, making it well-suited for evaluating typhoon-induced extreme precipitation, runoff, and wind speed impacts on forests.

Specifically, ERA5-Land provides the U component of 10 m wind (eastward) and V component of 10 m wind (northward). These two components were combined to calculate the horizontal 10 m wind speed and direction, and the maximum wind speed used in this study corresponds to the peak value derived from this calculation during the July 28–August 13 period.

Forest types and coverage

In addition, forest type and forest cover play a complex role in determining the extent of typhoon-induced disturbances. Different forest types and varying levels of canopy cover may exhibit different degrees of wind resistance during typhoon events47. In this study, forest type data were obtained from the Terra and Aqua combined MODIS land cover type product (MCD12Q1, Version 6.1), which includes a range of forest cover classifications. Forest cover data were derived from the Terra MODIS vegetation continuous fields (VCF) product. Designed to provide continuous representation of the Earth’s land surface, the VCF product offers proportional estimates of three surface cover components: percent tree cover, percent non-tree vegetation, and percent bare ground. The detailed information of all the aforementioned data is provided in Table 3.

Distance from typhoon track or landfall point

This study also assessed the impact of the typhoon on forests using the distance from forests to the typhoon track and landfall point. Specifically, we used the Euclidean distance analysis tool in ArcGIS 10.6 to generate distance data from the typhoon landfall point and track. First, a multi-layer buffer was set around the typhoon landfall point, categorizing distances into five ranges: 0–80 km, 80–160 km, 160–240 km, 240–320 km, and over 320 km. Additionally, distance buffers were generated along the typhoon track, dividing distances into six categories: 0–40 km, 40–80 km, 80–120 km, 120–160 km, 160–200 km, and over 200 km. This layered approach allows for a more detailed analysis of how wind speed changes with distance from the track and landfall point, assessing its impact on forest damage.

Assessment of forest loss caused by Doksuri

To quantitatively assess the extent of forest damage caused by typhoon, this study employs a univariate image differencing (UID) method based on NDVI, which effectively detects and quantifies the impact of typhoon disturbances48. First, forest areas are extracted to define the scope of typhoon disturbance evaluation. The NDVI image before the typhoon reflects the condition of healthy forests unaffected by the typhoon, while the NDVI image after the typhoon captures the vegetation changes caused by typhoon disturbance. Subsequently, ΔNDVI is calculated using Eq. (1) to quantitatively assess forest damage. Changes in ΔNDVI reveal the intensity of vegetation loss caused by typhoon disturbances, providing a remote sensing-based evaluation method. After standardization, ΔNDVI results illustrate the spatial distribution characteristics of forest damage.

To systematically assess the percentage of forest damage, canopy loss ratios (0–100%) were classified into four equal-interval categories, following thresholds informed by field surveys: <5%, 5–10%, 10–20%, and >20%49,50. The area and severity of forest damage were then analyzed at the grid-cell, city, and provincial levels.

Temporal analysis of typhoon impact and forest recovery

To comprehensively evaluate the impact of Typhoon Doksuri on forests in Fujian and its recovery progress, we conducted both short-term (three months) and longer-term (2010–2024) analyses using various methods to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the results. For short-term monitoring, forest loss and recovery were consecutively tracked using the most recent available imagery after the typhoon, as well as imagery within two and three months following the event. The area affected in the most recent post-typhoon imagery was defined as the initial damage extent, and short-term recovery was observed only within this area. This approach aims to exclude new forest loss that may occur due to seasonal changes or other factors, providing a more accurate assessment of the direct impact of Typhoon Doksuri and its short-term recovery dynamics.

To further quantify changes in forest conditions before and after the typhoon, we constructed a monthly NDVI time series from 2010 to 2024 using MODIS imagery on the GEE platform, covering the entire forest area, which may include secondary damage or new vegetation growth following the disturbance. By comparing the NDVI time series of the typhoon-affected years with those of unaffected years, we assessed the severity of forest disturbance caused by Typhoon Doksuri and conducted a cross-comparison of its relative impact level in recent events across Fujian Province.

Furthermore, to isolate the impact of the typhoon from temporal trends and other confounding factors and thus obtain more reliable estimates of its effects, we introduced a time-based difference-in-differences (DiD) model. In this design, the year 2023 was treated as the treatment year, with January–July defined as the pre-typhoon period and August–October as the typhoon-affected period. Two temporal baselines were selected as controls: (1) the corresponding months in 2022, representing a recent year unaffected by Typhoon Doksuri; and (2) the monthly averages from 2017 to 2022 for the same periods, serving as a multi-year reference. By comparing NDVI changes before and after the typhoon in 2023 with the corresponding changes in the control years, we identified the net NDVI loss attributable specifically to the typhoon.

Effects of parameters on forest disturbance

To explore the potential causes of differences in forest damage within areas with similar wind speeds and to explain the reasons for high damage in distant regions, we systematically analyzed various key influencing factors within the study area. First, to ensure consistency among multi-source data with different spatial resolutions, we resampled all datasets to a 500 m resolution using bilinear interpolation. Subsequently, we conducted a preliminary exploration using a simple linear regression model to examine the relationship between variables such as elevation, slope, aspect, wind exposure index, cumulative precipitation, cumulative runoff, forest type, canopy coverage, maximum wind speed, distance from the typhoon path and landfall point, and forest loss. The results were visualized using violin plots, providing a clear presentation of how each factor influences the degree of forest damage and highlighting differences in their effects, which helps to reveal the relationships and distribution characteristics between different factors and forest loss.

In addition, a multiple linear regression model was constructed using the least squares method to comprehensively analyze the combined effects of various factors on forest loss. The model used forest loss as the dependent variable, with all influencing factors as independent variables, including categorical variables such as forest type treated with dummy variables. Student’s t-tests were conducted to assess the significance of each variable (significance level α = 0.05), and the direction and strength of each variable’s impact on forest loss were quantified based on the size and sign of the regression coefficients, revealing the relative importance of each factor in the model.

Furthermore, SHAP analysis was employed to quantitatively assess the importance of variables in the model51. SHAP calculates Shapley values to measure the contribution of each variable to the prediction results, ranking their significance. Higher absolute SHAP values denote greater importance in predicting forest loss. Positive SHAP values indicate that the variable contributes to increased predicted damage, while negative values suggest a suppressing effect. Moreover, SHAP provides visualization tools such as dependence plots, which were used in this study to illustrate how changes in key variable values affect prediction trends, as well as to reveal interaction effects between variables.

Cross-validation using Sentinel-2 data

To cross-validate the MODIS-based analysis and assess potential scale effects, we further employed Sentinel-2 surface reflectance data to calculate the forest loss index (ΔNDVI). First, we compared the value distributions of ΔNDVI derived from MODIS and Sentinel-2 and visualized the results using bar charts with standard deviations. Subsequently, the Sentinel-2 ΔNDVI was aggregated to the spatial resolution of MODIS, and a pixel-level correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the comparability and robustness of the results across different spatial resolutions.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Chang, Y.-P., Yang, S.-C., Lin, K.-J., Lien, G.-Y. & Wu, C.-M. Impact of tropical cyclone initialization on its convection development and intensity: a case study of Typhoon Megi (2010). J. Atmos. Sci. 77, 443–464 (2020).

Murakami, H. et al. Future changes in tropical cyclone activity projected by the new high-resolution MRI-AGCM. J. Clim. 25, 3237–3260 (2012).

Wang, F. & Xu, Y. J. Comparison of remote sensing change detection techniques for assessing hurricane damage to forests. Environ. Monit. Assess. 162, 311–326 (2010).

Li, K. & Li, G. S. Risk assessment on storm surges in the coastal area of Guangdong Province. Nat. Hazard. 68, 1129–1139 (2013).

Li, L., Kareem, A., Xiao, Y., Song, L. & Zhou, C. A comparative study of field measurements of the turbulence characteristics of typhoon and hurricane winds. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 140, 49–66 (2015).

Morimoto, J. et al. Risk assessment of forest disturbance by typhoons with heavy precipitation in northern Japan. For. Ecol. Manage. 479, 118521 (2021).

Webster, P. J., Holland, G. J., Curry, J. A. & Chang, H.-R. Changes in tropical cyclone number, duration, and intensity in a warming environment. Science 309, 1844–1846 (2005).

Everham, E. M. & Brokaw, N. V. Forest damage and recovery from catastrophic wind. Botan. Rev. 62, 113–185 (1996).

Lin, T.-C., Hogan, J. A. & Chang, C.-T. Tropical cyclone ecology: a scale-link perspective. Trends Ecol. Evol. 35, 594–604 (2020).

Meiya, W. & Hanqiu, X. Remote sensing-based assessment of vegetation damage by a strong typhoon (Meranti) in Xiamen Island, China. Nat. Hazard. 93, 1231–1249 (2018).

Tanner, E. V., Kapos, V. & Healey, J. Hurricane effects on forest ecosystems in the Caribbean. Biotropica 23, 513–521 (1991).

Rossi, E., Rogan, J. & Schneider, L. Mapping forest damage in northern nicaragua after Hurricane Felix (2007) using MODIS enhanced vegetation index data. GISci. Remote Sens. 50, 385–399 (2013).

Abbas, S., Nichol, J. E., Fischer, G. A., Wong, M. S. & Irteza, S. M. Impact assessment of a super-typhoon on Hong Kong’s secondary vegetation and recommendations for restoration of resilience in the forest succession. Agric. For. Meteorol. 280, 107784 (2020).

Hall, J. et al. Hurricane-induced rainfall is a stronger predictor of tropical forest damage in Puerto Rico than maximum wind speeds. Sci. Rep. 10, 4318 (2020).

Xu, S. et al. The damage of urban vegetation from super typhoon is associated with landscape factors: evidence from Sentinel-2 imagery. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 104, 102536 (2021).

Cremer, K., Borough, C., McKinnell, F. & Carter, P. Effects of stocking and thinning on wind damage in plantations. N. Z. J. For. Sci. 12, 244–268 (1982).

Martin, T. J. & Ogden, J. Wind damage and response in New Zealand forests: a review. N. Z. J. Ecol. 30, 295–310 (2006).

Gardiner, B. Wind damage to forests and trees: a review with an emphasis on planted and managed forests. J. For. Res. 26, 248–266 (2021).

Bohn, F. J. & Huth, A. The importance of forest structure to biodiversity–productivity relationships. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4, 160521 (2017).

Jucker, T. et al. Topography shapes the structure, composition and function of tropical forest landscapes. Ecol. Lett. 21, 989–1000 (2018).

Zhu, H. et al. Monoculture plantations impede forest recovery: Evidence from the regeneration of lowland subtropical forest in Hong Kong. Front. For. Global Change 6, 1098666 (2023).

Finnigan, J. et al. Boundary-layer flow over complex topography. Boundary Layer Meteorol 177, 247–313 (2020).

Lee, M.-F., Lin, T.-C., Vadeboncoeur, M. A. & Hwong, J.-L. Remote sensing assessment of forest damage in relation to the 1996 strong typhoon Herb at Lienhuachi Experimental Forest, Taiwan. For. Ecol. Manage. 255, 3297–3306 (2008).

Reppucci, A., Lehner, S., Schulz-Stellenfleth, J. & Brusch, S. Tropical cyclone intensity estimated from wide-swath SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 48, 1639–1649 (2010).

Ren, Y. et al. Effects of climate change on vegetation growth in the Yellow River Basin from 2000 to 2019. Remote Sens 14, 687 (2022).

Shalamzari, M.J. & Zhang, W. Assessing water scarcity using the water poverty index (WPI) in Golestan Province of Iran. Water 10, 1079 (2018).

Ghalehteimouri, K. J., Ros, F. C., Rambat, S. & Nasr, T. Spatial and temporal water pattern change detection through the normalized difference water index (NDWI) for initial flood assessment: a case study of Kuala Lumpur 1990 and 2021. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Thermal Sci. 114, 178–187 (2024).

Guo, X. -y, Zhang, H. -y, Wang, Y. -q & Clark, J. Mapping and assessing typhoon-induced forest disturbance in Changbai Mountain National Nature Reserve using time series Landsat imagery. J. Mountain Sci. 12, 404–416 (2015).

Macamo, C., Massuanganhe, E., Nicolau, D., Bandeira, S. & Adams, J. Mangrove’s response to cyclone Eline (2000): what is happening 14 years later. Aquat. Bot. 134, 10–17 (2016).

Negrón-Juárez, R., Baker, D. B., Chambers, J. Q., Hurtt, G. C. & Goosem, S. Multi-scale sensitivity of Landsat and MODIS to forest disturbance associated with tropical cyclones. Remote Sens. Environ. 140, 679–689 (2014).

Peereman, J., Hogan, J. A. & Lin, T.-C. Assessing typhoon-induced canopy damage using vegetation indices in the Fushan Experimental Forest, Taiwan. Remote Sens. 12, 1654 (2020).

Taylor, A. R., Dracup, E., MacLean, D. A., Boulanger, Y. & Endicott, S. Forest structure more important than topography in determining windthrow during Hurricane Juan in Canada’s Acadian Forest. For. Ecol. Manage. 434, 255–263 (2019).

Feng, Y., Negrón-Juárez, R. I. & Chambers, J. Q. Multi-cyclone analysis and machine learning model implications of cyclone effects on forests. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 103, 102528 (2021).

Feng, Y., Negrón-Juárez, R. I. & Chambers, J. Q. Remote sensing and statistical analysis of the effects of hurricane María on the forests of Puerto Rico. Remote Sens. Environ. 247, 111940 (2020).

Nearing, M. et al. Modeling response of soil erosion and runoff to changes in precipitation and cover. Catena 61, 131–154 (2005).

Snyder, K. A., Scott, R. L. & McGwire, K. Multiple year effects of a biological control agent (Diorhabda carinulata) on Tamarix (saltcedar) ecosystem exchanges of carbon dioxide and water. Agric. For. Meteorol. 164, 161–169 (2012).

Chen, N. et al. The compensation effects of post-drought regrowth on earlier drought loss across the Tibetan plateau grasslands. Agric. For. Meteorol. 281, 107822 (2020).

Idris, M. H., Kuraji, K. & Suzuki, M. Evaluating vegetation recovery following large-scale forest fires in Borneo and northeastern China using multi-temporal NOAA/AVHRR images. J. For. Res. 10, 101–111 (2005).

Burton, P. J., Svoboda, M., Kneeshaw, D. & Gottschalk, K. W. Options for promoting the recovery and rehabilitation of forests affected by severe insect outbreaks. Restor. Boreal Temperate Forest. 495, (2015).

Foster, D. R., Knight, D. H. & Franklin, J. F. Landscape patterns and legacies resulting from large, infrequent forest disturbances. Ecosystems 1, 497–510 (1998).

Stanturf, J. A., Goodrick, S. L. & Outcalt, K. W. Disturbance and coastal forests: a strategic approach to forest management in hurricane impact zones. For. Ecol. Manage. 250, 119–135 (2007).

Lin, T.-C. et al. Typhoon disturbance and forest dynamics: lessons from a northwest Pacific subtropical forest. Ecosystems 14, 127–143 (2011).

Hoque, M. A.-A., Phinn, S., Roelfsema, C. & Childs, I. Tropical cyclone disaster management using remote sensing and spatial analysis: a review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 22, 345–354 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Biophysical impacts of earth greening can substantially mitigate regional land surface temperature warming. Nat. Commun. 14, 121 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Evapotranspiration on a greening Earth. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 626–641 (2023).

Yan, Y. et al. Climate-induced tree-mortality pulses are obscured by broad-scale and long-term greening. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 912–923 (2024).

Gao, Q. & Yu, M. Canopy density and roughness differentiate resistance of a tropical dry forest to major hurricane damage. Remote Sens. 13, 2262 (2021).

Liu, S., Marinelli, D., Bruzzone, L. & Bovolo, F. A review of change detection in multitemporal hyperspectral images: Current techniques, applications, and challenges. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 7, 140–158 (2019).

Yang, D. et al. Typhoon damage caused by Rammasum to trees in Haikou and its prevention measures. J. Fujian Forest. Sci. Technol. 42, 159–163 (2015).

Qiu, M., Wang, R., Ding, D., Mao, J. & Liao, B. Impact of” Rammasun” on Mangrove Communities in Dongzhaigang, Hainan. Ecol. Sci. 35, 118–122 (2016).

Chen, H., Covert, I. C., Lundberg, S. M. & Lee, S.-I. Algorithms to estimate Shapley value feature attributions. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 590–601 (2023).

Amatulli, G. et al. A suite of global, cross-scale topographic variables for environmental and biodiversity modeling. Sci. Data 5, 1–15 (2018).

Muñoz Sabater, J. ERA5-land monthly averaged data from 1981 to present. Copernicus climate change service (C3S) climate data store (CDS). Earth System Science Data 10, 4349–4383 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2023YFF0807000), the Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Natural Disasters of the Ministry of Education, Beijing Normal University (2023-KF-15), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42461144214), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Research Foundation (2024A1515030078), the Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (JCYJ20240813114013017), the Natural Science Foundation of Wuhan (2024040801020279), and the Guided Project of Hubei Provincial Department of Education (B2023246). The authors sincerely thank the Key Laboratory of Environmental Change and Natural Disasters of the Ministry of Education, Beijing Normal University, for providing valuable resources and support throughout this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Xu Zhang: writing—original draft, visualization, validation, software, methodology, formal analysis, data curation, conceptualization. Xiang Zhang: writing—review and editing, conceptualization, methodology, and visualization. Chao Yang: writing—review and editing and visualization. Aminjon Gulakhmadov: writing—review and editing and visualization. Wenying Du: writing—review and editing and visualization. Xihui Gu: writing—review and editing and visualization. Guiyu Li: writing—review and editing and visualization. Panda Rabindra Kumar: writing—review and editing and visualization. Veber Afonso Figueiredo Costa: writing—review and editing and visualization. Mahlatse Kganyago: writing—review and editing and visualization. Won-Ho Nam: writing—review and editing and visualization. Qi Wei: writing—review and editing and visualization. Yu Qian: writing—review and editing and visualization. Nengcheng Chen: writing—review and editing and visualization.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Yang, C. et al. Remote sensing and statistical assessment of the impact of typhoon Doksuri on subtropical forests in China. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 96 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00151-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00151-x