Abstract

Extreme heat events in the Middle East have become increasingly frequent and intense due to human-driven climate change. During the Hajj pilgrimage in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, in June 2024, temperatures soared to a record-breaking 51.8 °C, resulting in the tragic deaths of at least 1300 pilgrims and over 2700 non-fatal injuries. Our analysis of future projections, tailored for the region, indicates that in a warmer climate, such hazards may become a regular occurrence. Addressing these challenges through effective climate mitigation and adaptation is essential to building resilience against future extreme heat risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Middle East is warming nearly two times faster than the global average rate1. At the same time, the region is emerging as one of the most prominent global emitters of greenhouse gases1. Another distinct feature of the Middle East is that warming trends are more robust during the already scorching summer season2, while extremely high temperatures are increasing particularly rapidly3. The Arabian Peninsula is a climate change hotspot where heat extremes are emerging as a new normal, and this trend is expected to continue for the coming decades4. Longer and more intense heatwaves will likely pose the greatest challenge imposed by climate change1,5. This implies significant impacts on ecosystems and various socio-economic activities6. Due to the extreme and often degraded environmental conditions7, human health risks have been the focus of many regional assessments8,9,10,11,12.

The Muslim pilgrimage of Hajj, one of the five pillars of Islam, takes place mostly outdoors in and around Mecca in Saudi Arabia13. It is performed over five to six days, specifically from the 8th to the 12th or 13th of Dhul Hijjah, the twelfth month of the Islamic lunar calendar. The series of rites requires good mental and physical health due to the nature of outdoor rituals such as Wuquf, an afternoon of prayer and contemplation at Mount Arafat, which for some pilgrims follows a 15-kilometer walk from Mina14. During this and other rites, pilgrims often encounter stressors due to prolonged walking amidst large crowds, traversing rough terrain, wearing specific outfits, and exposure to weather conditions. Nearly half of Hajj pilgrims are older than 56 years, and about half have preexisting health conditions15. Extreme hot conditions represent a health risk to elderly people, since sweating capacity and skin blood flow reduce with age, reducing the ability to dissipate heat16. Heat exhaustion and, heatstroke, along with infectious diseases, including respiratory viral infections, are health hazards often associated with the Hajj pilgrimage17,18,19,20.

The total number of pilgrims in 2023 exceeded 1.8 million, while in 2024, a similar number of pilgrims were registered. During that year’s Hajj, local and international media reported that at least 1300 pilgrims lost their lives due to the extreme heat, which at Mecca’s Grand Mosque reached a scorching high of 51.8 °C20. According to media reports, about 83% of the deceased were pilgrims who had embarked on the journey without the necessary permits. That left them with little protection from the heat (e.g., access to air-conditioned facilities or food and water stations).

A rapid attribution study was published by ClimaMeter21 a few days after the event22. It suggested that extreme temperatures were up to 2.5 °C higher than those recorded during the hottest heatwaves previously observed in the country. By comparing similar cases from the past (1979–2001) with those in the recent period (2001–2023), the analysis concluded that the exceptional characteristics of the event could largely be attributed to human-induced climate change. Extreme temperatures were exacerbated by a high-pressure system (heat dome) over the northern Arabian Peninsula, augmented by warm air advection from southern latitudes. A noteworthy feature of the ClimaMeter analysis is a shift in the seasonality of similar events. For instance, in the present period, similar events tend to occur mostly in June, while previously occurring in May22. Additionally, an increasing trend in the occurrence of analogues at a rate of two events per decade was identified. Considering the unprecedented nature of the heatwave, natural variability had a less pronounced impact, reinforcing the view that human-driven climate change is the primary factor behind this event’s severity22.

Given the impact of this extreme event, we present a statistical analysis that integrates station-based observations, satellite information, reanalysis data, and regional climate projections tailored to the region’s specificities. Our goal is to raise awareness about future occurrences by investigating whether human-induced climate change has contributed to this event and assessing if, and when, life-threatening hot weather conditions might become more likely. We also aim to encourage further studies on the causes and predictability of these record heat extremes, which are occurring earlier than previously projected. Finally, for bridging the gap between hazard characterization and actionable risk reduction strategies, we also discuss practical mitigation solutions for further consideration by policymakers.

Results

Analysis of the June 2024 Hajj heat event

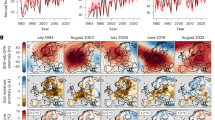

Our analysis of station observations shows the June 2024 event was record-breaking (Fig. 1e–f) and its peak was nearly 8 °C warmer than June’s climatology for 1985–2024 (average maximum temperature of 44.1 °C). Based on these observations, the expected return period of such an event is approximately once every 70 years (Fig. 1c). The ERA5-Land reanalysis data, available from the 1950s, substantially underestimate the daily maximum temperature and associated anomalies during the 2024 Hajj period when compared with station observations, despite their high resolution (Fig. 2a–d).

Projections of absolute daily maximum temperature (tasmax) in Mecca, Saudi Arabia, for the warm season (May to September), according to bias-adjusted MENA-CORDEX simulations presented as the multi-model ensemble mean and range under pathways RCP4.5 (a) and RCP8.5 (b). Blue bars in a, b indicate periods with Hajj in the warm season. Absolute maximum temperature and projected return periods of events analogous to the June 2024 case (c, d). Probability density functions (PDFs) of daily maximum temperature based on GSOD observations, raw and bias-adjusted (BC) MENA-CORDEX regional climate models (RCMs) for various periods (e, f). In e, f GSOD and RCM-BC HIST PDFs are overlapped.

Daily maximum temperature (a, b) and maximum temperature anomalies with respect to the 1951-2024 period, (c, d). Locations of Hajj primary sites are presented in (a) and (c). Humidex values (e) based on daily (+) and hourly (⨀) humidity and temperature values, as well as daily averaged Humidex from hourly values (⨁). Data source: ERA5-Land reanalysis data.

Atmospheric humidity can aggravate heat stress, reducing the effectiveness of the body’s evaporative cooling mechanism. Although Mecca generally experiences dry summer conditions, it is situated within the circulation zone of the Red Sea breeze, which frequently brings moisture. Relying on daily averages for atmospheric humidity, may lead to under- or overestimating thermal stress indicators23. Consequently, due to the lack of sub-daily data from observations, we calculated the Humidex index for thermal comfort, based on the ERA5-Land reanalysis. Despite the overall temperature underestimation, hourly Humidex values exceeded the “Dangerous Conditions” threshold on several days during the Hajj period (Fig. 2e). Notably, Humidex values calculated from daily average temperature and humidity (Daily Humidex) are substantially lower than those derived from hourly data (Hourly and Hourly-to-Daily Humidex).

Future temperature extremes in Mecca

By analyzing a set of bias-adjusted climate projections optimized for the region, we explored whether such extreme heat events may become more frequent and similarly intense. For this, we explored an intermediate (RCP4.5) and a business-as-usual pathway (RCP8.5). While some RCP8.5 projections indicate that during the most extreme years, temperatures nearing 52 °C could be reached within the coming two decades, such events will become more common in the second half of the century (Fig. 1b). The longer-term projections indicate that around 2070, there is a high probability that on an annual basis the absolute maximum temperature in Mecca could exceed the June 2024 record, which is used here as a benchmark. For comparison, the intermediate greenhouse gas emission pathway (RCP4.5) suggests that for the remainder of the century, exceedance is expected only during the hottest years and in the most extreme projections (Fig. 1a).

Relative to our reference period (1985–2024), future projections indicate that the mean value of daily maximum temperatures will further rise by an average of 1.4 °C between 2021 and 2060 (Fig. 1b), and by 3.6 °C towards the latter part of the century (2061–2100). In addition to these changes, an increase in the standard deviation of maximum temperatures (i.e., from 1.1 to 1.6 °C) indicates greater year-to-year variability and more pronounced extremes. By the end of the 21st century and during the extended summer season from May to September, the business-as-usual scenario indicates a 3.4% probability of individual summer days exceeding 51.8 °C (Fig. 1f). For pathway RCP4.5, this probability is only 0.3% (Fig. 1e).

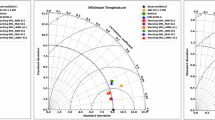

An extreme value analysis shows that even after bias adjustment, the MENA-CORDEX projections remain conservative in predicting the absolute extremes. For instance, during the historical simulations, extreme daily temperatures comparable to the June 2024 event are expected to occur once every 80 to 200 years, with most models indicating a return period of about 100 years (Fig. 1d). In the upcoming decades (2021–2060), this return period will significantly decrease to once every one or two decades. An indicative example is presented in Fig. 3. For RCP8.5, in the latter part of the century (2061–2100), the current record of 51.8 °C is likely to occur annually or even multiple times each year (Figs. 1d and 3f). Even considering the stabilization pathway (RCP4.5), the expected return period of such events will be reduced to once every 3 to 12 years (Figs. 1c and 3e).

Based on the Generalized Extreme Value distribution (GEV) and Maximum Likelihood (ML) statistical approaches (see Methods) for the GSOD observations (a) and CESM-WRF-CYI (RCM4) historical simulation (b) and projections for pathways RCP4.5 (c, e) and RCP8.5 (d, f). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) are also indicated. The orange star symbols denote the expected return periods of events with temperatures similar to the June 2024 extreme record (51.8 °C).

Since the Islamic calendar is lunar, the Gregorian calendar dates of Hajj vary each year17, meaning it does not always take place during the warmest months (Fig. 1a–b). For the next several years, up to 2028, Hajj will occur in May, a time that is typically considered part of the extended summer period. Therefore, it is crucial to exercise extreme caution and avoid situations similar to the 2024 case. During 2048–2061, the Hajj will again be within the extended summer season. However, under both pathways, the average conditions during that period are unlikely to exceed those observed in June 2024. In contrast, towards the end of the century (2081–2094), daily maximum temperatures during Hajj could reach or even far exceed 51.8 °C. According to the high-end scenario and models, the most extreme temperatures can reach or slightly exceed 57 °C.

Discussion

Our analysis suggests that the exceptional event of June 2024 represents typical extreme conditions towards the second half of the century if current trends continue. The record-breaking temperature of nearly 52 °C illustrates the potential threats climate change could pose to major outdoor gatherings, such as the Hajj pilgrimage, under business-as-usual scenarios. Considering that the intensity and persistence of this heatwave exceed all recorded analogues in the available historical record, it may be considered statistically unprecedented within the context of the observed climate. Nonetheless, rare extremes may still occur under natural variability, and attribution analysis using ClimaMeter21 aims precisely to quantify the relative contributions of anthropogenic forcing versus natural variability. For example, while there is strong evidence that anthropogenic warming contributed to the severity of this event22, other analyses indicate that the 2023–24 El Niño may have also increased the risk of record-breaking temperatures in the Arabian Peninsula and other locations worldwide24.

Given the overall underestimation of temperatures in the MENA-CORDEX simulations5, the present results may represent a lower limit for the business-as-usual future. Compared to some studies25, the present results rely on a relatively small set of climate models. However, this regional ensemble is tailored to the Middle East and offers invaluable guidance for future climate assessments. The comparison with the more optimistic pathway RCP4.5 highlights the importance of timely climate mitigation actions.

The current analysis on future projections did not consider the effect of humidity on exacerbating thermal discomfort, an aspect that has been assessed previously13,19,26. This omission was due to data limitations and findings from the 2024 case study, analyzed here, which demonstrate that using daily averages in such extreme environments significantly underestimates discomfort.

Besides the extreme heat, excess dust loadings (Supplementary Fig. 1) may have increased discomfort and played a synergistic role in augmenting the heat impact. In these environments, poor air quality significantly worsens health risks alongside extreme heat. Τhe Middle East has become a hotspot for air pollution due to increasing human-made emissions, which rival the natural desert dust7. Air pollution is a leading health risk factor in the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, where approximately 15% of mortality can be attributed to poor air quality7. High air pollution levels adversely affect the respiratory and cardiovascular systems, especially affecting vulnerable populations such as the elderly and individuals with pre-existing health conditions.

In addition to Hajj, another minor pilgrimage known as Umrah attracts pilgrims to Mecca throughout the year. According to the Saudi Government’s Vision 2030, the number of Umrah pilgrims alone will reach 30 million by 203027. Although the rituals of Umrah are generally less physically demanding, they can draw significant crowds, especially during the holy month of Ramadan. The increasing number of pilgrims, combined with warmer conditions and more frequent, longer-lasting and intense heatwaves5, could further increase the health burden.

In 2025, the number of casualties and non-fatal injuries was highly reduced thanks to milder weather conditions and new rules. In this context, understanding historical and future heat extremes is essential for sustained adaptation. Recommended measures should evolve with climatic trends through regular reassessments, technological upgrades, and alignment with long-term projections. A dual approach—addressing immediate risks during upcoming hot periods while preparing for future high-risk cycles—supports climate-resilient and sustainable Hajj management. Adaptation measures also differ in their timelines: operational responses can be implemented quickly, whereas large-scale infrastructure and urban design improvements require longer planning and investment horizons.

For example, heat exposure risks could be addressed by a combination of cooling solutions specifically designed for large-scale outdoor pilgrim events such as the Hajj28. Cool pavement technologies, including reflective coatings and permeable water-retentive systems, have demonstrated significant mitigation potential in urban environments and could be adapted for pilgrim sites29,30. Super cool paints with high solar reflectance and strong mid-IR emissivity can also be employed for large-scale built surfaces and shading elements to reduce heat loads31. These materials could be applied to ritual site pavements, temporary structures, and pilgrimage pathways, providing immediate thermal relief for pedestrians. For vulnerable groups, e.g., pilgrims with limited access to air-conditioned facilities, targeted interventions could include strategically placed shaded rest areas utilizing high-emissivity canopy materials, evaporative cooling systems for public spaces, and hydration stations equipped with cooling infrastructure. The integration of these passive cooling technologies with adaptive work-rest scheduling and heat stress monitoring protocols, as successfully implemented for outdoor workers in extreme climates32, can provide an additional approach to protecting pilgrims during peak heat exposure periods.

Despite major progress in reducing heat-related mortality and morbidity during the Hajj through infrastructure improvements33, medical preparedness34, and operational coordination, the rising frequency and intensity of heat extremes in the Arabian Peninsula calls for the optimization and evaluation of these measures. Existing interventions—such as shading networks, misting systems, and air-conditioned facilities—should be systematically evaluated using microclimate, health, and behavioral data. Although operational early warning systems exist, their effectiveness can be improved by enhancing predictive capability and user integration. Saudi Arabia’s health authorities have made remarkable advances in Hajj medical planning; the next step is to integrate real-time health analytics. Linking hospital admission data, emergency calls, and field clinic reports in real time can allow proactive resource allocation and faster case detection. Future strategies should emphasize co-designed risk communication campaigns developed with scholars of Islamic jurisprudence, ensuring messages align with religious observance.

Many of the heat mitigation measures discussed can be effectively applied to other mass religious gatherings—including the Kumbh Mela in India and Arba’in pilgrimage in Iraq—where extreme weather also poses significant challenges, and the uniquely harsh desert environment of Mecca may serve as an important testbed for adapting to future climate conditions that other regions may increasingly encounter as global temperatures rise. While mitigation measures and technological advancements can moderate impacts, several challenges remain and are likely to worsen as greenhouse gas concentrations continue to rise. This is relevant for outdoor labor activities or cultural and religious events, such as the Hajj, especially when they occur during the hottest months. To effectively assess and address the impacts of climate change in a region characterized by extreme environmental conditions, limited resources and diverse cultural backgrounds, it is essential to raise awareness and enhance research and dissemination.

Methods

Observations and projections

Daily maximum temperature observations for the warm season of the year (May to September) were retrieved from the NOAA’s National Centers of Environmental Information Global Summary of the Day portal (GSOD). The Mecca (or Makkah) station (21.43 °N, 39.76 °E) is situated on the city’s outskirts at an elevation of 240 meters above the mean sea level and approximately 60 km from the Red Sea coast. Its location is about 5 km east of Masjid al-Haram, also known as the Sacred Mosque or the Great Mosque of Mecca. The analysis was complemented by the ERA5-Land reanalysis data35.

The IASI/Metop-A ULB-LATMOS dust optical depth dataset36 is based on a flexible and robust dust retrieval algorithm from measurements of the Infrared Atmospheric Sounding Interferometer (IASI). It is based on the calculation of a hyperspectral range index and subsequent conversion to optical depth at 10 microns via a neural network.

We considered an ensemble of nine MENA-CORDEX simulations available at 50-km horizontal resolution (Supplementary Table 1). Our ensemble is the result of combining six global and four regional climate models. The dynamical downscaling follows the CORDEX guidelines37. Future climate projections (2006–2100) are presented for the “business-as-usual” Representative Concentration Pathway RCP8.538. The scenario period for RCPs begins in the year 2005. As a result, a significant part of what we consider historical conditions (1985–2024) is influenced by scenario-driven emissions. Comparing historical emissions does not yield definitive conclusions for this period. For instance, for 2010, the RCP8.5 scenario underestimates emissions, whereas the opposite is found for 202039. Fewer MENA-CORDEX simulations were available for RCP4.5. Nevertheless, these were also used to assess whether reducing greenhouse gas concentrations has an impact on alleviating heat extremes. RCP4.5 is an intermediate scenario that implies emission reductions and stabilizes radiative forcing at 4.5 W m−2 by the year 210040.

Bias adjustment

The MENA-CORDEX ensemble tends to underestimate temperature5. For Mecca, this underestimation can be attributed to the misrepresentation of elevation at the spatial resolution of the climate models. In addition, the driving global models may have also played a role, e.g., due to their inability to simulate sea surface temperatures in the Red Sea at coarse resolution. Therefore, before any further analysis of climate model output, we have applied a bias adjustment of daily maximum temperature using the GSOD station observations as a reference. This adjustment is based on the Quantile Delta Mapping (QDM) method41. This approach uses a transfer function to equate the cumulative distribution functions of observed and modeled data series while it preserves absolute changes in quantiles, e.g., for variables like temperature42.

Extreme value analysis

To obtain the return periods of the annual absolute maximum temperature and compare them with the 51.8 °C record-high reported in Mecca, we applied the commonly used generalized extreme value (GEV) distribution43. To estimate the location, scale and shape parameters, we used the Maximum Likelihood (ML) approach44. This approach has been used in other studies to analyze heat extremes45. For this analysis, we used 40-year periods, a historical reference (1985–2024), that also allows a comparison with observations and two future periods, 2021–2060 (21C1) and 2061–2100 (21C2). Before the extreme value analysis, the time series were tested to confirm the absence of significant trends within these sub-periods.

Humidex calculations

The Thermal Comfort Index Humidex for daily or hourly data series, based on the formula purposed by Masterton and Richardson46 and ERA5-Land reanalysis data. These calculations were based on (i) average daily humidity and near-surface temperature, (ii) hourly humidity and temperature and (iii) average daily Humidex values derived from (ii).

Data availability

Data are available at https://github.com/gzittis/Hajj-2024-study.git.

References

Zittis, G. et al. Climate change and weather extremes in the eastern Mediterranean and Middle East. Rev. Geophys. 60, e2021RG000762 (2022).

Hadjinicolaou, P., Tzyrkalli, A., Zittis, G. & Lelieveld, J. Urbanisation and geographical signatures in observed air temperature station trends over the Mediterranean and the Middle East–North Africa. Earth Syst. Environ. 7, 649–659 (2023).

Almazroui, M., Islam, M. N., Dambul, R. & Jones, P. D. Trends of temperature extremes in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 808–826 (2014).

Zittis, G., Lazoglou, G., Hadjinicolaou, P. & Lelieveld, J. Emerging extreme heat conditions as part of the new climate normal. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 155, 143–150 (2024).

Zittis, G. et al. Business-as-usual will lead to super and ultra-extreme heatwaves in the Middle East and North Africa. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 20 (2021).

Waha, K. et al. Climate change impacts in the Middle East and Northern Africa (MENA) region and their implications for vulnerable population groups. Reg. Environ. Change 17, 1623–1638 (2017).

Osipov, S. et al. Severe atmospheric pollution in the Middle East is attributable to anthropogenic sources. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 203 (2022).

Hajat, S., Proestos, Y., Araya-Lopez, J. L., Economou, T. & Lelieveld, J. Current and future trends in heat-related mortality in the MENA region: a health impact assessment with bias-adjusted statistically downscaled CMIP6 (SSP-based) data and Bayesian inference. Lancet Planet Health 7, e282–e290 (2023).

Al-Bouwarthan, M., Quinn, M. M., Kriebel, D. & Wegman, D. H. Assessment of heat stress exposure among construction workers in the hot desert climate of Saudi Arabia. Ann. Work Expo. Health 63, 505–520 (2019).

Ahmadalipour, A. & Moradkhani, H. Escalating heat-stress mortality risk due to global warming in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA). Environ. Int. 117, 215–225 (2018).

Pal, J. S. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Future temperature in southwest Asia projected to exceed a threshold for human adaptability. Nat. Clim. Chang 6, 197–200 (2016).

Neira, M. et al. Climate change and human health in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East: literature review, research priorities and policy suggestions. Environ. Res 216, 114537 (2023).

Kang, S., Pal, J. S. & Eltahir, E. A. B. Future heat stress during muslim pilgrimage (Hajj) projected to exceed “extreme danger” levels. Geophys Res. Lett. 46, 10094–10100 (2019).

Aldossari, M., Aljoudi, A. & Celentano, D. Health issues in the Hajj pilgrimage: a literature review. East. Mediterranean Health J. 25, 744–753 (2019).

Memish, Z. A. Health of the Hajj. Science (1979) 361, 533–533 (2018).

Millyard, A., Layden, J. D., Pyne, D. B., Edwards, A. M. & Bloxham, S. R. Impairments to thermoregulation in the elderly during heat exposure events. Gerontol. Geriatr. Med. 6, (2020).

Gatrad, A. R. & Sheikh, A. Hajj: journey of a lifetime. BMJ 330, 133–137 (2005).

Alandijany, T. A. Respiratory viral infections during Hajj seasons. J. Infect. Public Health 17, 42–48 (2024).

Saeed, F., Schleussner, C.-F. & Almazroui, M. From Paris to Makkah: heat stress risks for Muslim pilgrims at 1.5 °C and 2 °. C. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 024037 (2021).

Haghani, M. Hajj pilgrims suffer from climate extremes. Science (1979) 385, 1426–1426 (2024).

Faranda, D. et al. ClimaMeter: contextualizing extreme weather in a changing climate. Weather Clim. Dyn. 5, 959–983 (2024).

Faranda, D. & Alberti, T. Saudi Arabia June 2024 heatwave mostly exacerbated by human-driven climate change. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14103905 (2024).

Diaconescu, E., Sankare, H., Chow, K., Murdock, T. Q. & Cannon, A. J. A short note on the use of daily climate data to calculate Humidex heat-stress indices. Int. J. Climatol. 43, 837–849 (2023).

Jiang, N. et al. Enhanced risk of record-breaking regional temperatures during the 2023–24 El Niño. Sci. Rep. 14, 2521 (2024).

Malik, A. et al. Accelerated Historical and Future Warming in the Middle East and North Africa. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos 129, e2024JD041625 (2024).

Raymond, C., Matthews, T. & Tuholske, C. Evening humid-heat maxima near the southern Persian/Arabian Gulf. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 591 (2024).

Yezli, S. et al. Umrah. An opportunity for mass gatherings health research. Saudi Med J. 38, 868–871 (2017).

Yezli, S., Ehaideb, S., Yassin, Y., Alotaibi, B. & Bouchama, A. Escalating climate-related health risks for Hajj pilgrims to Mecca. J. Travel Med. 31, (2024).

Santamouris, M. Using cool pavements as a mitigation strategy to fight urban heat island—a review of the actual developments. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 26, 224–240 (2013).

García-Melgar, P. et al. Mitigating urban heat pains through nature-based cool pavement in extremely hot climates. Energy Build 343, 115945 (2025).

Wang, J., Yan, D., Ding, L., An, J. & Santamouris, M. On the development of super cool paints for cooling purposes. Sol. Energy 296, 113592 (2025).

Habibi, P. et al. Climate change and heat stress resilient outdoor workers: findings from systematic literature review. BMC Public Health 24, 1711 (2024).

Alghamdy, S., Alleman, J. E. & Alowaibdi, T. Cool white marble pavement thermophysical assessment at Al Masjid Al-Haram, Makkah City, Saudi Arabia. Constr. Build Mater. 285, 122831 (2021).

Nashwan, A. J., Aldosari, N. & Hendy, A. Hajj 2024 heatwave: addressing health risks and safety. Lancet 404, 427–428 (2024).

Muñoz-Sabater, J. et al. ERA5-Land: a state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 13, 4349–4383 (2021).

Clarisse, L. et al. A decadal data set of global atmospheric dust retrieved from IASI satellite measurements. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 124, 1618–1647 (2019).

Giorgi, F. & Gutowski, W. J. Coordinated experiments for projections of regional climate change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 2, 202–210 (2016).

Riahi, K. et al. RCP 8.5-A scenario of comparatively high greenhouse gas emissions. Clim. Change 109, 33–57 (2011).

Strandsbjerg Tristan Pedersen, J. et al. An assessment of the performance of scenarios against historical global emissions for IPCC reports. Glob. Environ. Change 66, 102199 (2021).

Thomson, A. M. et al. RCP4.5: a pathway for stabilization of radiative forcing by 2100. Clim. Change 109, 77–94 (2011).

Cannon, A. J., Sobie, S. R. & Murdock, T. Q. Bias correction of GCM precipitation by quantile mapping: How well do methods preserve changes in quantiles and extremes? J. Clim. 28, 6938–6959 (2015).

François, B., Vrac, M., Cannon, A. J., Robin, Y. & Allard, D. Multivariate bias corrections of climate simulations: which benefits for which losses? Earth Syst. Dyn. 11, 537–562 (2020).

Jenkinson, A. F. The frequency distribution of the annual maximum (or minimum) values of meteorological elements. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 81, 158–171 (1955).

Prescott, P. & Walden, A. T. Maximum likelihood estimation of the parameters of the generalized extreme-value distribution. Biometrika 67, 723–724 (1980).

Berghald, S., Mayer, S. & Bohlinger, P. Revealing trends in extreme heatwave intensity: applying the UNSEEN approach to Nordic countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 034026 (2024).

Masterton, J. M. & Richardson, F. A. Humidex: a method of quantifying human discomfort due to excessive heat and humidity. Environ. Can. 45, pp (1979).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the EMME-CARE project that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program, under Grant Agreement no. 856612, as well as matching co-funding by the Government of Cyprus. This publication is based upon work from COST Action FutureMed (CA22162), supported by COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.Z. conceived the study. G.Z., M.A., F.D., P.H., L.K., G.N., and T.O. carried out the MENA-CORDEX simulations and curated data. G.Z., G.L., D.Far., D.Fra., and A.T. carried out the analyses. G.Z., D.Far., P.H., S.O., T.A., M.T. and J.L. wrote the first draft. G.Z., T.A., M.A., F.D., D.Far., D.Fra., P.H., L.K., G.L., G.N., S.O., T.O., G.S., M.T., R.Z., and J.L. discussed the results. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zittis, G., Alberti, T., Almazroui, M. et al. Analysis of the 2024 Hajj heat event and future temperature extremes in Mecca. npj Nat. Hazards 2, 107 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00159-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44304-025-00159-3