Abstract

The deterministic and stochastic control of nonlinear dynamics in magnetic solitons is crucial for future information processing technologies. Yet, the transition to chaos in such systems remains largely unexplored. Here, we demonstrate that a confined magnetic vortex, when driven by a rotating in-plane magnetic field under low excitation, follows well-defined trochoidal trajectories in its core motion. We classify these trajectories using a trochoidal constant that captures the competition between the intrinsic gyrotropic frequency and the frequency of the external drive. This parameter determines both the rotational symmetry of the orbit and the number of core-trajectory revolutions required for closure. Beyond a critical excitation threshold, the underlying trochoidal symmetry breaks down, giving rise to a vortex-core reversal process that evolves into fully chaotic dynamics. We construct a dynamic phase diagram identifying distinct regimes of locked, quasi-periodic, and chaotic reversals. Importantly, the vortex core functions as a field-driven binary oscillator with extreme sensitivity to initial conditions, enabling deterministic yet unpredictable switching behavior. Our findings reveal a mechanism of driving-induced chaotic dynamics in topological magnetic textures, with potential applications in unconventional computing platforms such as stochastic spintronic logic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nonlinear dynamics of topologically protected magnetic textures, such as magnetic vortices and skyrmions, have attracted considerable attention due to their rich responses to external stimuli1,2,3. These solitonic structures serve as versatile platforms for energy-efficient, logic-capable spintronic devices4,5. While the gyrotropic motion of vortex cores has been widely studied under linear excitation6,7, their behavior under strongly nonlinear driving conditions remains largely unexplored, particularly in regimes where core trajectories become deformed and polarity reversals emerge2,6,7,8.

Magnetic nonlinear systems are known to exhibit rich dynamics ranging from periodic oscillations to deterministic chaos, with implications for emergent information processing schemes such as chaos computing5 and random-bit generation9,10. Despite this promise, most prior studies have focused on steady-state or weakly nonlinear vortex dynamics6,7,8, leaving the chaotic regime and its transition mechanisms largely unaddressed.

In this study, we show that a magnetic vortex confined in a single nanodot or cross-shaped nanostructure exhibits trochoidal trajectories with well-defined rotational symmetries and traversal patterns. Beyond a critical field threshold, these symmetric orbits break down, leading to chaotic core reversals that depend on the applied field amplitude and frequency. By introducing a geometric descriptor, the trochoidal constant, we classify orbital symmetries and closure behavior in the weak-field excitation regime. Furthermore, we identify a rich phase space consisting of locked, quasi-periodic, and chaotic regimes of vortex-core reversals. This system also exhibits SDIC, a hallmark of deterministic chaos9,11,12, thereby demonstrating stochastic unpredictability under infinitesimal perturbations. By bridging geometric orbital dynamics with chaotic switching phenomena, this study lays the groundwork for experimentally accessible, chaos-engineered nanomagnetic systems for unconventional computing architectures.

Results

Model geometries and spin textures

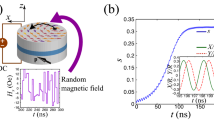

Our model system comprises either a circular Permalloy (Py, Ni80Fe20) disk or a cross-shaped Py nanostructure, which support magnetic vortices and antivortices, respectively (see Fig. 1). Using zero-temperature micromagnetic simulations performed with MuMax3 software13, we obtained ground states, characterized by the vorticity (V = +1 for vortices and V = –1 for antivortices). Each state is further defined by the in-plane curling magnetization, the chirality C, where C = +1 corresponds to counterclockwise (CCW) and C = –1 to clockwise (CW), and by the core polarity P, with P = +1 for upward core magnetization and P = –1 for downward.

a Geometry and spin structure of two nanostructures used in this study: a circular disk (300 nm in diameter, 10 nm thick) and a cross-shaped element composed of two orthogonal arms (600 nm arm length, 200 nm width, 10 nm thick), each supporting either a magnetic vortex (vorticity V = +1) or an antivortex (V = −1). Colors indicate the in-plane magnetization orientation, while the brightness of the central region represents the out-of-plane core magnetization. b Four possible ground states defined by chirality (C = ±1) and polarity (P = ±1). Circular panels depict vortex configurations in the disk, while square panels represent antivortex configurations in the cross. White arrows indicate the direction of magnetization circulation.

Each ground state was then subjected to a circularly rotating in-plane field, Hrot(t) = h[(cos(2\(\pi\)ft)\(\hat{x}\) + sin(2\(\pi\)ft)\(\,\hat{y}\)), where the sign of f determines the sense of rotation: CCW for f > 0, and CW for f < 0. Hereafter, we define the normalized field amplitude as H = h/hs and the normalized frequency as F = f/fo, where hs (= 500 Oe) is the static field required to expel the vortex core, and fo (~ 0.325 GHz) is the intrinsic gyrotropic resonance frequency as obtained from simulations (see Supplementary Fig. 1). Further details of the simulation are provided in Methods and the Supplementary Materials.

Trochoidal orbits of vortex core motion under weak-field excitation

We systematically varied H from 0.01 to 1.0 and |F| from 0.1 to 10.0 for both signs, mapping vortex-core trajectories and polarity reversals across a broad parameter range, tracked over a 100 ns trace including both transient and long-term dynamics. The vortex core motion was recorded via the guiding-center position R(t)=[X(t), Y(t)]; further details are provided in Supplemental Section 1.

Figure 2 presents a systematic comparison of vortex and antivortex core trajectories across all four combinations of chirality (C = ± 1) and polarity (P = ± 1), under either CCW (F > 0) or CW (F < 0) field rotation with a fixed |F | = 1/4, in weak-field excitations (H ≲ 0.01). Each panel illustrates the trajectory of the vortex or antivortex core in the x-y plane over an initial 12 ns window, with time encoded by color from blue (early) to yellow (late). The direction of each closed orbit, indicated by green (CW) or purple (CCW) arrows, matches the external field rotation for vortices but is opposite for antivortices, reflecting the reversal of the intrinsic gyrotropic sense in the antivortex case and the resulting field-dominated dynamics. This is because the sense of a core’s gyrotropic motion is determined by the sign of the gyrovector, which is reversed for the antivortex14. When the intrinsic rotation of the vortex core (depending on P) and the applied drive rotate in the same sense (P\(\cdot\)F > 0), the resulting orbits are epitrochoid-like, when they are opposed (P\(\cdot\)F < 0) the orbits become hypotrochoid-like (for a detailed description of the trochoidal geometry, see Supplementary Fig. 2).

Trochoidal trajectories of vortex and antivortex cores under rotating in-plane magnetic fields with frequency ratio F = f/f0 = 1/4 for CCW and CW rotation fields. The panels are arranged in a 4 × 4 matrix, and each panel contains the four different [C, P] states. Epitrochoid- and hypotrochoid-type orbits appear for P \(\cdot\)F > 0 and P \(\cdot\)F < 0, respectively. Time evolution is color-coded from blue (early) to yellow (late) over a 12 ns interval. Green (purple) arrows show CW (CCW) rotation of the orbit.

For example, for either V = +1 or V = –1, three-lobed trajectories are observed when P\(\cdot\)F > 0, while five-lobed trajectories appear when P\(\cdot\)F < 0. To classify the trochoidal geometry under the weak-field excitation, we introduce the trochoidal constant \(\nu\) = |1 – P\(\cdot\)F | . This constant defines the geometric factor of the orbit, expressed as a rational number \(\nu =n/m\), where n determines the rotational symmetry of the orbit (i.e., the number of lobes), and m is the closure index, indicating how many revolutions of the guiding center are needed to complete one full closed orbit. Further geometric details and visual illustrations of n and m are provided in Supplementary Fig. 2. Specifically, in Fig. 2, when the intrinsic core gyration and field rotation are in the same sense, epitrochoid-like trajectories appear with \({\rm{\nu }}=3/4\,\left(i.e.,{n}=3,{m}=4\right).\) In this case, the direction of the orbit matches the revolution of the guiding center. In contrast, when the rotation senses are opposed, resulting in hypotrochoid-like orbits with \(\nu =5/4\,\left(i.e.,{n}=5,{m}=4\right)\), where the trajectory rotates opposite to the guiding center’s revolution. Importantly, the observed differences in lobe count, orbital symmetry, and rotation sense arise from the interplay between core polarity and the direction of field rotation. In contrast, chirality affects only the initial phase of the trajectory (i.e., the starting lobe position), without influencing its symmetry or closure properties.

Building on the fixed-drive comparison of the eight [V, C, P] states, we now systematically vary the normalized drive frequency F while keeping the vortex state [V, C, P] = [+1, +1, \(-\)1], in order to explore how a wide range of trochoidal constants \(\nu =\,|1-\,P\cdot{F|}\) produces diverse orbital geometries characterized by different rotational symmetries and closure conditions. Figure 3 shows a broad range of trochoidal geometries and symmetries for selected rational values of |F | = 1/4, 1/3, 1/2, 1, 2, 5/2, 3, and 4, while fixing the field amplitude at H = 0.01 (still in weak field region) in a 100 ns window. For a vortex with polarity P = –1 (CW intrinsic gyration), epitrochoid-like orbits emerge under CW fields (left column) since P\(\cdot\)F > 0, and hypotrochoid-like orbits under CCW fields (right column) since P\(\cdot\)F < 0. For each |F| , the trochoidal constant \(\nu\) is given by |1 – P\(\cdot\)F| and corresponds directly to the geometric factor n/m, provided that the greatest common divisor of n and m is 1. For example (top), when P\(\cdot\)F = (–1)\(\times\)(–1/4) = 1/4, the epitrochoid has ν = 3/4, yielding a 3-fold symmetry with m = 4. When P ∙ F = (–1) \(\times\) (+1/4) = –1/4, the corresponding hypotrochoid has ν = 5/4, yielding a 5-fold symmetry with the same step size m = 4. The same reasoning applies to other rational ratios, including |F| = 1/3, 1/2, 1, 2, 5/2, 3, and 4. Notably, when |F | =1 (fourth row), the epitrochoid (ν = 1) evolves into a spiral-like trajectory due to damping, resembling an Archimedean spiral. The corresponding hypotrochoid (ν = 2) yields a twofold elliptical trajectory. At |F| = 2 (fifth row), the epitrochoid corresponds to ν = 1 (n = 1, m = 1), forming a onefold limaçons of Pascal, while the hypotrochoid exhibits ν = 3 (n = 3, m = 1) resulting in a threefold symmetric shape. Other rational values of |F|, such as 1/3, 1/2, 5/2, and 3, similarly yield n-fold, multi-lobed symmetries governed by the relation ν (= n/m) = |1 – P\(\cdot\)F |. For the epitrochoid cases, v takes values of 2/3, 1/2, 3/2, and 2, while for the hypotrochoid cases, v is 3/4, 3/2, 7/2, and 4.

Guiding-center position R(X, Y) over 100 ns under rotating in-plane magnetic fields with either CW (F < 0, left column) or CCW (F > 0, right column) rotation. Time progression is color-coded from t = 0 ns (blue) to t = 100 ns (yellow). Trochoidal constant \(\nu\) (= n/m) determines the geometry of a closed trochoid: n is the number of lobes (or cusps), i.e. the curve possesses Cn rotational symmetry. m is the number of full revolutions made by the center of the rolling circle during one complete period of the curve.

Furthermore, an instructive example is provided by the same threefold symmetry (n = 3) in the P\(\cdot\)F > 0 condition, where the trochoidal constant takes values ν = 3/4, 3/2, and 3, corresponding to step size m = 4, 2 and 1, respectively. Although all three cases display three lobes, m determines both the lobe visitation sequence and the relative rotation sense of the trajectory and guiding center. The m = 4 case (ν = 3/4) is an epitrochoid with sequential lobe visitation in the same rotation sense as the guiding center. In contrast, the m = 2 (ν = 3/2) and m = 1 (ν = 3) case are hypotrochoids, with the former skipping every other lobe and the latter visiting lobes sequentially, both rotating opposite to the guiding center. A similar relationship between ν, n, and m, and traversal dynamics is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 3. These results indicate that the remainder of m mod n governs how the trajectory winds through lobes, either sequentially or with alternating skips.

By systematically sweeping ∣F∣ in the low-amplitude regime, vortex trajectories remain well described by classical trochoidal forms before nonlinear effects become significant. The variety of multi-lobed symmetries reveals how subtle variations in initial offset, damping, and rational frequency ratios collectively generate a rich spectrum of orbital patterns15. These results establish a baseline for identifying the threshold at which stronger fields induce complex or chaotic vortex dynamics, as discussed next.

Chaotic polarity reversal

The progressive deformation of trochoidal vortex-core trajectories beyond a critical threshold triggers deterministic polarity reversals, thereby linking geometric instability to the emergence of chaotic switching16,17. As the driving field amplitude H exceeds the linear-response regime, the effective gyration frequency fG deviates from its intrinsic value fo, leading to deformed or merged orbital paths6,14,15,16. Once a threshold velocity is reached, the core undergoes polarity reversal. Once the core is reversed, the core couples preferentially to the CW (or CCW) gyrotropic eigenmode allowed by the unidirectionally rotating drive field. In combination with the gyroforce, this yields an effective dynamic breaking of time-reversal symmetry, producing the strong resonance asymmetry between the two eigenmodes7,18. This leads to the onset of deterministic yet complex switching dynamics19,20,21,22,23,24. Figure 4a, b presents colormaps of the time-averaged topological charge <Q> over a 10 ns window in the [H, |F|] plane for F < 0 and F > 0, respectively, where \(Q=\frac{1}{4\pi }\int m\cdot \left({\partial }_{x}{\boldsymbol{m}}\times {\partial }_{y}{\boldsymbol{m}}\right){dx\; dy}\). Two distinct phase-locked regions, labeled IA and IB, emerge: in IA, the polarity remains down (P = − 1); in IB, it remains up (P = +1) after a single polarity reversal occur. No chaotic switching occurs within IA and IB, although the IB region (F > 0) exhibits mild sensitivity to initial states. Near F = − 1, resonant excitation enables polarity reversal at relatively low amplitudes (as early as H ≈ 0.09), typically producing a single flip from epitrochoid (P\(\cdot\)F > 1) to hypotrochoid (P\(\cdot\)F < 0) motion. At higher field amplitudes, chaotic switching and bifurcations emerge across broader parameter ranges. For the F > 0 case, multiple polarity reversals occur within region IB of the F < 0 case. In fact, in higher-amplitude regimes an alternative pathway, vortex–antivortex (V-AV) pair creation and annihilation, can also flip the polarity within sub-nanoseconds25. Outside the IA and IB regions, repeated polarity reversals signal entry into a chaotic regime. For ∣F∣ > 4 (magenta-dotted boxes), 〈Q〉 gradually shifts from −0.5 to +0.5 as H increases when F < 0, and in the opposite direction when F > 0. When F is varied at fixed H (green-solid boxes), a comparable polarity drift occurs, indicating that drive parameters can bias the final polarity state.

a, b Maps of 〈Q〉 over 10 ns, and c, d maps of LLE as functions of the normalized field amplitude H (horizontal axis) and the normalized frequency ∣F∣ (vertical axis). Panels (a) and (c) correspond to F < 0, while panels (b) and (d) correspond to F > 0. Regions IA and IB denote phase-locked states. The magenta-dotted and green-solid boxes mark zones exhibiting abrupt polarity transitions under small parameter variations26. In (c) and (d), red areas (\(\lambda\) > 0) marks deterministic chaos; blue (\(\lambda\) ≤ 0) indicates regular or quasi-periodic motion. The \(\lambda =0\) contour reproduces the phase boundaries.

To quantitatively confirm the presence of chaos, we computed the largest Lyapunov exponent (LLE, \(\lambda\)) from the time series of the topological charge Q(t), using the Rosenstein method26. The LLE provides a direct measure of sensitivity to initial conditions: positive values indicate exponential sensitivity to infinitesimal perturbations, while near-zero or negative values correspond to quasi-periodic or periodic motion. Figure 4c, d shows the resulting two-dimensional maps of \(\lambda\) over the [H, |F | ] plane with both F > 0 and F < 0. Red regions (\(\lambda\) > 0) correspond to chaotic regimes, while blue regions (\(\lambda\) < 0) denote ordered motion. Importantly, the \(\lambda\) = 0 contour matches the boundaries between phase-locked and chaotic regions identified in Fig. 4a, b, thereby quantitatively validating our dynamic phase classification. These results reveal that chaotic vortex dynamics remain deterministic and strongly influenced by system parameters, with polarity outcomes biased, not random, due to the underlying attractor structure.

Sensitive dependence on initial conditions

While the λ diagrams confirm the presence and boundaries of chaos in parameter space, we next turn to a time-domain analysis to illustrate how the SDIC manifests across these regions. To this end, we first quantify the system’s instability by evaluating how small perturbations in the initial vortex state affect the subsequent evolution of Q(t) under the same driving conditions. We define the first core polarity reversal time tc1 as the earliest time when Q(t) changes its initial sign (i.e., the moment of first core reversal). Figure 5a presents a phase map of tc1 values over the [H, | F | ] parameter space for F < 0, subdividing the chaotic domain into three distinct regions, IIA, IIB, and IIC.

a Phase diagram showing the subdivision of the chaotic regime by the first core-reversal time tc1 for F < 0, with subregions labeled IIA, IIB, and IIC. White regions (upper left) correspond to no reversals (region IA). The dotted line indicates the boundary of region IB. Each subregion exhibits a different level of chaotic sensitivity: higher tc1 (yellow) corresponds to delayed first flips, whereas lower tc1 (blue) indicates earlier and more frequent reversals. Five red dots mark the representative [H, F] values. b Time traces of Q (t) for two nearly identical initial conditions (IC1: purple, IC2: cyan) with the same vortex configuration [V, C, P] = [+1, +1, \(-\)1]. The chosen field parameters [H, F] are, from top to bottom, [0.5, \(-\)5], [0.8, \(-\)2], [0.4, \(-\)1], [0.6, \(-\)8], and [0.9, \(-\)8], as marked by red dots in (a).

To analyze specific features in these regions, we calculated the time evolution of Q(t) under each of five representative [H, F] drive conditions, marked as red dots, for two nearly identical initial vortex states. Both trajectories, IC1 (purple) and IC2 (cyan), differ only by a minute perturbation in initial conditions (ΔQ0 ≈ 10−9) for the same vortex topology [V, C, P] = [+1, +1, −1]. At [H, F] = [0.5, −5] in regime IA, both trajectories remain locked near Q ~ −0.5 throughout the 10 ns window, showing no divergence (first panel in Fig. 5b). At [H, F] = [0.8, −2] in region IB (second panel), both ICs flips coherently from –0.5 to +0.5 with no divergence, consistent deterministic reversal. At [H, F] = [0.4, −1] in region IIA (third panel), the two trajectories remain identical until ~6 ns, after which they bifurcate, marking the onset of chaos. At [H, F] = [0.6, –8] in region IIB (fourth panel), divergence begins earlier ( ~ 4 ns), followed by multiple switching events. At [H, F] = [0.9, –8] in IIC (last panel), the trajectories bifurcate within ~2 ns followed by irregular switching behavior, occasionally exceeding Q > 0.5, consistent with strong chaos or transient multi-vortex states. These large Q excursions in region IIC reflect the temporary formation of V–AV pairs or topological defects. Such multi-core states typically decay via annihilation, restoring a single vortex configuration. This chaotic behavior is consistent with prior simulation studies25,27.

Together, these time-domain results demonstrate how deterministic chaos emerges gradually from stable, polarity-locked motion to strongly sensitive and irregular switching across well-defined regions of parameter space, illustrating the system’s SDIC, a hallmark of deterministic chaos9,11,12,28,29. These results highlight the tunable nature of vortex-core chaos under rotating magnetic fields and sets the stage for understanding its functional implications in the discussion that follows.

Discussion

Our findings present a unique physical realization of deterministic chaos in a minimal topological system under purely field-driven excitation. Unlike prior studies that rely on spin-transfer torques or feedback loops to induce chaotic dynamics, the use of rotating in-plane fields provides a more intuitive and geometrically transparent means to control symmetry breaking and state transitions.

This work highlights the potential of using magnetic vortex cores as nonlinear oscillators whose polarity encodes binary information. The deterministic yet highly sensitive dynamics resemble the behavior of stochastic bits (probabilistic bits)10,16, which are foundational components in probabilistic computing and physical reservoir computing frameworks. With vortex gyration frequencies in the gigahertz range, the demonstrated polarity reversals can support high-speed bit generation for unconventional information processing.

Furthermore, the use of a trochoidal constant to classify and predict multi-lobed orbital symmetry provides a universal geometric language applicable not only to magnetic vortices but also to other solitonic entities such as skyrmions, chiral domain walls, and optical vortices1,5. These results suggest a broader universality of nonlinear geometric motion across different physical platforms.

Importantly, the simulated configurations and field conditions are experimentally accessible with current nanofabrication and magnetic excitation technologies. Rotating fields can be implemented via orthogonal electrodes or phase-shifted waveforms, and vortex states can be reliably initialized and detected using magnetic force microscopy or time-resolved magneto-optical techniques. These factors enhance the feasibility of translating our predictions into functional spintronic elements.

Taken together, this work advances the fundamental understanding of nonlinear topological dynamics while opening new directions for information processing using chaos-engineered nanomagnetic systems.

In summary, we demonstrate a dynamical transition from structured trochoidal orbits to irregular, chaotic polarity reversals in confined magnetic vortices, driven purely by rotating in-plane magnetic fields. This transition arises from the interplay between intrinsic gyrotropic motion and external rotational forcing, breaking time-reversal symmetry and destabilizing the vortex core. The onset of chaos is geometrically captured by a trochoidal constant, which classifies the orbit symmetry and closure conditions via rational frequency locking16. Our findings reveal a fully deterministic yet tunable route to vortex-core chaos, offering a robust physical mechanism for generating pseudo-random switching in spin-based devices. This controlled chaos enables practical implementations in probabilistic logic, neuromorphic computing, and hardware random-number generation, all within experimentally accessible nanomagnetic platforms.

Methods

Micromagnetic simulation

Micromagnetic simulations were performed using MuMax3 to solve the Landau–Lifshitz–Gilbert (LLG) equation13. A fixed cell size of 2 × 2 × 10 nm³ was chosen to balance computational accuracy and efficiency, with a Dormand–Prince solver used to maintain an error threshold of 10−5. To prepare ground states, each magnetic configuration was initialized in the designated vortex geometry of [V, C, P] and relaxed. To extract the intrinsic gyration frequency, we applied a sinc-pulse field along the y-direction, and performed a fast-Fourier transformation (FFT) of the vortex-core’s guiding center. Details regarding simulation parameters, vortex state preparation, frequency extraction, topological charge evaluation, and dynamic phase mapping are provided in the accompanying Supplementary Materials.

Data availability

Data supporting this study's findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Guslienko, K. Y. et al. Nonlinear gyrotropic vortex dynamics in ferromagnetic dots. Phys. Rev. B 82, 014402 (2010).

Moon, K.-W. et al. Duffing oscillation-induced reversal of magnetic vortex core by a resonant perpendicular magnetic field. Sci. Rep. 4, 6170 (2014).

Shen, L. et al. Nonlinear dynamics of directly coupled skyrmions in ferrimagnetic spin torque nano-oscillators. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 48 (2024).

Luo, S. et al. Reconfigurable Skyrmion logic gates. Nano Lett. 18, 2 (2018).

Park, G. & Kim, S.-K. Reconfigurable all-in-one chaotic computing with skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 174420 (2024).

Yoo, M.-W., Mineo, F. & Kim, J.-V. Analytical model of the deformation-induced inertial dynamics of a magnetic vortex. J. Appl. Phys. 129, 053903 (2021).

Lee, K.-S. & Kim, S.-K. Two circular-rotational eigenmodes and their giant resonance asymmetry in vortex gyrotropic motions in soft magnetic nanodots. Phys. Rev. B 78, 014405 (2008).

Lee, K.-S. & Kim, S.-K. Gyrotropic linear and nonlinear motions of a magnetic vortex in soft magnetic nanodots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 132511 (2007).

Yoo, M.-W. et al. Pattern generation and symbolic dynamics in a nanocontact vortex oscillator. Nat. Commun. 11, 601 (2020).

Phan, N.-T. et al. Unbiased random bitstream generation using injection-locked spin-torque nano-oscillators. Phys. Rev. Appl. 21, 034063 (2024).

Taniguchi, T. Chaotic magnetization dynamics driven by feedback magnetic field. Phys. Rev. B 109, 214412 (2024).

Hamadeh, A. A. et al. Diverse dynamics in interacting vortices systems through tunable conservative and non-conservative coupling strengths. Commun. Phys. 8, 204 (2025).

Vansteenkiste, A. et al. The design and verification of MuMax3. AIP Adv. 4, 107133 (2014).

Guslienko, K. Y. et al. Eigenfrequencies of vortex state excitations in magnetic submicron-size disks. J. Appl. Phys. 91, 8037–8039 (2002).

Carvajal, D. A., Riveros, A. & Escrig, J. Orbit-like trajectory of the vortex core in ferrimagnetic dots close to the compensation point. Results Phys. 19, 103598 (2020).

Yamada, K. et al. Electrical switching of the vortex core in a magnetic disk. Nat. Mater. 6, 270–273 (2007).

Park, G. Chaos dynamics in topologically nontrivial spin textures and its applications to chaos and probabilistic computing. PhD thesis, Seoul National University (2024).

Guslienko, K. Y., Lee, K.-S. & Kim, S.-K. Dynamic origin of vortex core switching in soft magnetic nanodots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 027203 (2008).

Petit-Watelot, S. et al. Commensurability and chaos in magnetic vortex oscillations. Nat. Phys. 8, 682–687 (2012).

Devolder, T. et al. Chaos in magnetic nanocontact vortex oscillators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 147701 (2019).

Lee, K.-S., Yoo, M.-W., Choi, Y.-S. & Kim, S.-K. Edge-soliton-mediated vortex-core reversal dynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 147201 (2011).

Abdizadeh, S., Abouie, J. & Zakeri, K. Dynamical switching of confined magnetic skyrmions under circular magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. B 101, 024409 (2020).

Chen, Y.-F. et al. Nonlinear gyrotropic motion of skyrmion in a magnetic nanodisk. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 458, 123–128 (2018).

Park, G. & Kim, S.-K. Emergence of chaos in magnetic-field-driven skyrmions. Phys. Rev. B 108, 174441 (2023).

Lee, K.-S., Guslienko, K. Y., Lee, J.-Y. & Kim, S.-K. Ultrafast vortex-core reversal dynamics in ferromagnetic nanodots. Phys. Rev. B 76, 174410 (2007).

Rosenstein, M. T., Collins, J. J. & De Luca, C. J. A practical method for calculating largest Lyapunov exponents from small data sets. Phys. D65, 117–134 (1993).

Lee, K.-S., Kang, B.-W., Yu, Y.-S. & Kim, S.-K. Vortex–antivortex pair driven magnetization dynamics studied by micromagnetic simulations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 85, 1547–1549 (2004).

Imai, Y., Nakajima, K., Tsunegi, S. & Taniguchi, T. Input-driven chaotic dynamics in vortex spin-torque oscillator. Sci. Rep. 12, 21651 (2022).

Holmes, P. Poincaré, celestial mechanics, dynamical-systems theory and “chaos. Phys. Rep. 193, 137–163 (1990).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT, South Korea (Grant No. RS-2024-00347921). and Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (Grant No. IO201229-08274-01). The Institute of Engineering Research at Seoul National University provided additional research facilities for this work. S.-K.K. appreciates B.K. for assistance in finalizing the manuscript during the revision stage.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.P. conceived the main idea and designed and analyzed the micromagnetic simulations under the supervision of S.-K.K. S.-K.K. guided the project throughout G.P.’s Ph.D and wrote this manuscript based on G.P.’s dissertation17, which was received in August 2024. B.K. contributed to performing the LLE calculations and to finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, G., Kim, B. & Kim, SK. From trochoidal symmetry to chaotic vortex-core reversal in magnetic nanostructures. npj Spintronics 3, 42 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00108-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00108-w