Abstract

Cavity magnonics, a hybrid platform bridging photonics and spintronics, faces a fundamental challenge in reconciling ultra-strong light-matter interactions with nonreciprocal signal control. By introducing a yttrium iron garnet defect into a photonic crystal, we demonstrate ultra-strong coupling with a coupling strength of 1.18 GHz and 10.9% energy transfer efficiency at room temperature. Time-reversal symmetry breaking via gyromagnetic and Faraday effects induces nonreciprocal microwave transmission within the photonic bandgap, achieving 20 dB isolation over a 1.2 GHz bandwidth. Crucially, the emergent isolation functionality originates from fundamental magnon-photon coupling control rather than engineered device optimization, providing a phenomenological framework for coherent signal manipulation in hybrid quantum systems. Our simultaneous realization of ultra-strong and nonreciprocal coupling at room temperature establishes a new paradigm for scalable quantum transducers and reconfigurable microwave isolators, overcoming the cryogenic limitations of superconducting systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the past few decades, light-matter interactions have been extensively studied. The strength of interactions is typically described by the coupling strength. When the coupling strength reaches the order of the bare frequency of the system, the system enters the ultra-strong coupling (USC) regime1,2,3,4. In this regime, the dynamical behaviors of the system undergo significant changes, providing a new platform for quantum information processing and quantum calculation5,6,7,8,9.

As a prominent example of such interactions, cavity magnonics has emerged as a versatile platform for exploring hybrid systems10,11,12,13,14. In this regime, information is encoded and transmitted through polariton quasiparticles that arise from the strong coupling between magnons and photons. Since the pioneering work of Soykal and Flatté in 2010, who first proposed the concept of magnon-photon coupling15,16, significant progress has been made in both experimental realizations and theoretical developments, including coherent coupling17,18,19, dissipative couplings20,21,22, indirect couplings23,24,25, long-Distance Coherence26,27, nonreciprocal couplings (NRC)28,29,30,31,32,33.

Particularly, NRC plays a crucial role in enabling unidirectional signal transmission28,29. This is of great importance for designing novel isolation devices based on cavity magnonics, as it can prevent interference from reflected signals, thereby enhancing the stability and efficiency of the system. However, to achieve nonreciprocity over a broader frequency range, it is necessary to maximize the coupling strength. In previous studies, nonreciprocal magnon-photon coupling required the introduction of significant external dissipation, achieved through the cooperation between coherent and dissipative coupling28. However, high dissipation tends to constrain the coupling strength, making it challenging for the system to reach the USC regime. As a result, the simultaneous realization of NRC and USC in cavity magnonics has remained a persistent challenge for researchers. Since Zhang et al. proposed realizing USC at high frequencies by increasing the size of the yttrium iron garnet (YIG) sphere while reducing the microwave cavity dimensions18, several researchers have successively demonstrated USC at both low34,35,36,37,38,39 and room temperatures40. In previous work, we realized the USC in a two-dimensional (2D) photonic crystal (PC) with a YIG cylinder defect at room temperature, achieving the coupling strength of 1.05 GHz and an energy transfer efficiency of 11.7%41. In addition, we achieved the nonreciprocal strong coupling in a system composed of an irregular cavity and large-scale YIG wafer by the gyromagnetism and Faraday effect, enabling the control of unidirectional microwave transmission29. These works provide new insights and methodologies for achieving simultaneous NRC and USC in cavity magnonics.

In this work, we firstly demonstrate the simultaneous realization of USC and NRC within the photonic bandgap of a PC. We achieve an ultra-strong coupling strength of 1.18 GHz, with an energy transfer efficiency of 10.9%. The breaking of time-reversal symmetry (TRS) in the system, induced by the gyromagnetic and Faraday effects, enables nonreciprocal microwave transmission within the bandgap. Specifically, by tuning the strength and direction of the applied magnetic field, microwaves are allowed to propagate preferentially along single direction, while transmission in the opposite direction is significantly suppressed. This work not only advances the understanding of cavity magnonics in photonic crystals but also provides a foundational framework for developing novel nonreciprocal devices, such as a kind of functional wideband microwave isolation, in hybrid cavity magnonics systems.

Results

Experiment

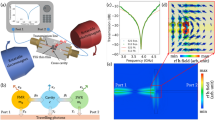

Figure 1 shows our measurement for the hybrid system. our system consists of a 2D PC with a point defect by substituting a YIG cylinder for a copper cylinder. A vector network analyzer (VNA, Agilent E8363B) is employed to feed microwaves by connecting it to two antennas. Meanwhile, a static magnetic field along the z direction is applied by an electromagnet.

a The 2D copper cylinder PC with a point defect of a YIG cylinder. All cylinders have a diameter of 5 mm and a height of 5 mm. The lattice constant is 20 mm. Two aluminum plates are applied to be the two-dimensional chamber with 5 mm of separation and surrounded by some microwave absorbing materials. Microwave signals are supplied by a VNA through two microwave cables with two antennas. The static magnetic field is applied in the z direction. b Experimental data. Microwave transmission coefficients S21 of the PC and YIG defect PC as a function of frequency without applied magnetic field. c and d represents the simulation result (by the finite element method) of the strength of microwave magnetic field distribution along z direction of the PC and YIG defect PC at 11.03 GHz, respectively. Black circle stands for the position of the YIG cylinder.

The scatter parameter Sij (i, j = 1, 2) is measured to characterize the experimental phenomena discussed later. Sij represents the microwave transmission signal from port j to port i. Figure 1b shows the transmission coefficients S21 of the copper cylinder PC and the YIG defect PC as a function of frequency. The microwave magnetic field distribution at 11.03 GHz in the PC and the YIG defect PC is illustrated in Fig. 1c, d, respectively. It reveals that a strong concentration of the magnetic energy can be observed at the position of the YIG cylinder [black circle on Fig. 1d]. This implies that a defect mode at 11.03 GHz within the band gap is excited, as observed in Fig. 1b. This mode is primarily determined by the geometrical structure of the PC with a YIG cylinder. Its resonant frequency reflects the localized electromagnetic state created by the point defect. Focusing on this defect mode, we swept the applied static magnetic fields over a frequency range between 10.0 and 11.5 GHz.

Nonreciprocal couplings in the band gap

Figure 2a, b displays the magnitude of the microwave transmission coefficients S21 and S12, respectively. The spectra were measured by altering the static magnetic field H from −9000 to 9000 Oe with a step size of 18 Oe. An anticrossing behavior arises because of the coupling between magnons and photons. According to our experiments, magnons are supplied by the FMR mode, and photons are introduced by the defect mode of the YIG defect. The FMR mode (black dashed line in Fig. 2 can be calculated using the Kittel equation42:

Here, γ is the gyromagnetic ratio with a value of 2.8 MHz/Oe. The demagnetizing factors cannot be calculated analytically, as the demagnetizing field is not uniform in cylindrically-shaped magnetized bodies. We used the experimental results of the demagnetizing factors of the cylinder with the same dimensional ratio from the textbook43. Consequently, the demagnetizing factors Nx, Ny, and Nz are set to values of 0.365, 0.365 and 0.27, respectively. It should be noted that the photon frequency ωP/2π is 10.8 GHz (red dashed line in Fig. 2) rather than 11.03 GHz. When the applied magnetic field H is 0, the YIG defect is in a demagnetized state. In this state, YIG exhibits a high effective relative permeability μr due to disordered magnetic domains. As H increases, μr decreases. The refractive index n can be expressed as \(n=\sqrt{{\mu }_{r}{\varepsilon }_{r}}\), therefore, as μr increases, n increases nonlinearly. When H is 480 Oe, the YIG cylinder is fully saturated magnetized, with magnetization aligned along +z or −z. According to photonic crystal theory44, the lower n decreases the resonant frequency of a point defect mode. Hence, we observe the fundamental defect mode at a higher frequency with 11.03 GHz and the real photon mode ωP at a lower frequency with 10.8 GHz.

Mapping of the amplitude of the microwave transmission as a function of frequency ω/2π and the applied static magnetic field H. The closer the color to blue, the larger is the microwave transmission loss. Black dashed line indicates the FMR mode, calculated with the Kittel equation [Eq. (1)] and red dashed line represents the photon mode. a S21 mapping. b S12 mapping.

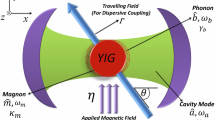

Unlike nonreciprocal microwave transmission induced by the cooperative effect of coherent and dissipative coupling in an open cavity-magnon system28, the nonreciprocity arises from the gyromagnetism effect and the Faraday effect in this work. As shown in Fig. 2, the closer the color to blue, the loss of microwave transmission.

First, we observe that before coupling, when the magnetic field is applied in the positive direction (z+), the photon mode manifests as a resonance peak in S12 and an antiresonance dip in S21. This behavior leads to a more efficient transmission of S12 when the FMR mode couples with the photon mode, with the coupled polariton modes manifesting as resonance peaks. In contrast, the transmission of S21 is significantly suppressed, and the coupled polariton mode exhibits an antiresonance dip. Then, we simulated the distribution of the microwave magnetic field along the z-direction in the YIG at a frequency of 10.8 GHz under an applied magnetic field of 490 Oe for both the S12 and S21 directions, using the finite element method. The results show that the energy diverges outward in the S12 direction, while it converges inward in the S21 direction, which agrees well with our experimental results (simulation details are provided in part II of the Supplemental Material45.). Furthermore, the direction of the applied magnetic field also significantly influences microwave transmission. For instance, in S21, when the applied magnetic field is negative (−z), the microwaves in the coupling region transmit more efficiently, whereas transmission is markedly suppressed when the field is positive. Conversely, the results observed in S12 exhibit the opposite behavior to those in S21.

To better understand the aforementioned phenomena, we present the permeability of the material. Note that the magnetic anisotropy of the YIG cylinder is induced by the applied magnetic field. When fully magnetized, the permeability μ will turn into a second-rank tensor μ as the microwave magnetic field is perpendicular to H. μ is given by46:

where \({\mu }_{r}=1+{\omega }_{K}{\omega }_{m}/({\omega }_{K}^{2}-{\omega }^{2})\), \({\mu }_{i}=-\omega {\omega }_{m}/({\omega }_{K}^{2}-{\omega }^{2})\). Here, ωm/2π = γMs is the characteristic frequency. The off-diagonal element in the permeability tensor is induced by the non-zero applied static magnetic field. It can be concluded that the permeability tensor μ is asymmetric (μxy ≠ μyx), leading to different effective medium parameters experienced by microwaves propagating in the S21 and S12 directions. When the magnetic field is applied along the +z direction, the energy propagating in the S12 direction is more efficiently enhanced by the resonance of the YIG, whereas the microwaves in the S21 direction cannot effectively couple back to port 1. In this case, the TRS of the system is broken47. The degree of TRS breakage is characterized as u = μi/μr46. For example, u comes to a value of 98.9% as H = 2000 Oe and ω/2π = 11.0 GHz. This implies a near-complete breaking of the TRS. Furthermore, the isolation ratio (ISO)28 can be calculated with a value of 20 dB in the coupling regime of Fig. 2, demonstrating a highly effective transmission of a unidirectional signal (calculation details are provided in part II of the Supplementary Material45.).

Additionally, it is important to note that, in previous studies of cavity-magnonics, small-scale YIG spheres (with diameters less than or equal to 1 mm) were commonly used as magnetic materials to excite magnons. However, in this work, the diameter of the YIG cylinder reaches 5 mm. Within the frequency range of 10–11 GHz, the effective wavelength of microwaves passing through the YIG is ~7.7–6.7 mm, which is comparable to the size of the YIG. When microwaves propagate through the YIG, the Faraday rotation angle accumulates linearly with the propagation distance due to the Faraday effect. The larger the YIG diameter, the more pronounced this cumulative effect becomes. This cumulative effect is the core mechanism behind the non-reciprocal microwave transmission: When the rotation direction of the polarization plane aligns with the applied magnetic field, energy is transmitted efficiently; conversely, when the rotation direction opposes the applied magnetic field, a mode mismatch occurs at the ports, leading to energy loss.

In addition, the YIG cylinder is not located on the axis of symmetry of the PC, and the antennas are not placed symmetrically. These operations are also helpful for increasing the nonreciprocity in the system (researchers often introduce ferrites into resonant cavities with irregular shapes to break the TRS of the systems in many studies about quantum chaos)48,49,50,51.

To better validate the rationality of NRC, we performed numerical calculations using input-output theory52. Unlike systems where nonreciprocity originates from the competition between coherent and dissipative couplings28, the nonreciprocity in our system arises from gyromagnetism and Faraday rotation. This results in symmetric anticrossing for both S21 and S12 individually, but a significant difference in transmission amplitude between them. The transmission coefficients are given by:

Here, J/2π and Γ/2π are the coherent coupling strength and the dissipative coupling strength, with a value of 1.18 and 0.01 GHz, respectively. α/2π and β/2π are the intrinsic damping rate of the magnon mode and the photon mode with a value of 0.011 GHz (calculating from the linewidth of the YIG cylinder), and 0.1 GHz (fitting from the defect mode shown in Fig. 2), respectively. γ/2π and κ/2π are the external damping rates of the magnon mode and the photon mode, respectively, where γ = Γ2/κ45. The sign ± captures the direction-dependent boundary phase shift caused by gyromagnetism and Faraday rotation, where the sign + corresponds to the favored direction and the sign − corresponds to the suppressed direction. The numerical results are illustrated in Fig. 3, using J/2π =1.18 GHz, Γ/2π = 0.01 GHz, and κ/2π = 0.1 GHz. Similarly, the closer the color is to blue, the loss is the microwave transmission. It can be observed that the numerical results align well with the experiment results shown in Fig. 2. Moreover, the coherent coupling strength J/2π derived from Eq. (3) is significantly greater than the dissipative coupling strength Γ/2π, exceeding it by more than a factor of 100. This demonstrates that the nonreciprocal coupling observed in this work does not originate from the competition between coherent and dissipative coupling in the system. The coupling efficiency η is determined to be 10.9% (η = J/ωP, with dissipative coupling strength being negligible), achieving the ultra-strong coupling regime.

Microwave transmission as a function of frequency ω/2π and the applied static magnetic field H, calculated with input-output theory [Eq. (3)]. The closer the color to blue, the larger is the microwave transmission loss. a S21mapping; b S12mapping.

Ultra-strong coupling

In order to demonstrate that our system has reached the USC regime theoretically, we conducted a more in-depth analysis of the coupling based on the system’s Hamiltonian. Typically, the strong coupling between the cavity photon mode and the FMR mode can be described by two coupled harmonic oscillators, with the Hamiltonian given by the Dicke model17,18:

where \({\widetilde{\omega }}_{P}={\omega }_{P}+i\beta \), \({\widetilde{\omega }}_{K}={\omega }_{K}+i\alpha \), and \(\widetilde{g}=J+i\Gamma \). The three terms on the right-hand side of the Eq. (4) represent the photon mode, the FMR mode, and the interaction between the two modes, respectively. In the strong coupling regime, the rotating-wave approximation18 (RWA) can be employed to solve the Hamiltonian, which involves neglecting the counter-rotating terms \({\hat{c}}^{\dagger }{\hat{b}}^{\dagger }\) and \(\hat{c}\hat{b}\). This approach has been widely applied in cavity magnonics. However, when the system operates in the USC coupling regime, the RWA is no longer valid, and counterrotating terms must be taken into account3.

In the USC regime, the Hopfield model is often used instead of the Dicke model to study the system. In this case, the Hamiltonian is given by3,53,:

where \({\rm{\Lambda }}={\widetilde{g}}^{2}/{\widetilde{\omega }}_{K}\) is the diamagnetic term to ensure gauge invariance, providing a physically consistent description of the polariton eigenfrequencies, given by the Thomas–Reiche–Kuhn sum rule40. Then, we obtain the eigenvalues by solving the Hamiltonian of the system under these conditions:

where \({\widetilde{\omega }}_{\pm }\) are frequencies of the polariton modes, and \(\widetilde{g}/2\pi \) is coupling strength. In this work, the coupling efficiency has just reached the threshold of the USC regime, and the system has not entered the superradiant phase. In addition, λ is a phenomenological prefactor to capture the different renormalizations observed in the polariton energies, which accounts for the reduction of the diamagnetic term53. The prefactor λ serves as a fitting parameter, and it is especially notable that the value obtained depends on the coupling strength53. In this work, the coupling has just reached the threshold of the USC regime. Therefore, a small value with 0.05 for λ was used to modify Λ, reflecting the suppressed diamagnetic response in our system. As shown in Fig. 4, the blue dots represent the experimental data, while the black curves correspond to the polarized modes ω± obtained by fitting Eq. (6). The coherent coupling strength and dissipative coupling strength are fit as J = 1.18 GHz and Γ = 0.01 GHz, respectively, which are consistent with the results obtained from Eq. (3). This confirms that our system has indeed reached the USC regime5. In the ultra-strong coupling region, the stronger the coupling strength, the stronger the nonreciprocity29.

a S21 direction; b S12 direction.The experimental data are described as blue dots. Black dashed line indicates the FMR mode fitting with the Kittel equation [Eq. (1)]; red dashed line indicates the photon mode located at 10.8 GHz; black curves are coupling curves calculated with modified Hopfield model model [Eq. (6)]. Bandgap is marked by dashed gray box.

Such unique dynamic behaviors enable flexible controllability. In addition, another ultra-strong magnon-photon coupling is observed at the bottom right of Fig. 2, marked by the gray solid ellipses. We designed another experiment to understand the origin of this coupling and noted that both the magnon mode and the photon mode are provided by the YIG cylinder simultaneously35,54,55. The coupling strength reaches 4 GHz, and the coupling efficiency is 32.8%. Experimental and calculation details are provided in part III of the Supplemental Material45. While we confirm the phenomenon experimentally, its full quantum implications require new models for self-resonance. This is the focus of an in-depth study where we have made significant progress, expecting to publish them separately once we have fully understood all the physical mechanisms involved.

Functional wideband microwave isolation

Our work establishes a functional example for microwave isolation by harnessing the synergy of nonreciprocal ultra-strong magnon-photon coupling. It is crucial to distinguish between the observation of a strong nonreciprocal phenomenon and the engineering of a packaged isolator device. Unlike engineered devices, this phenomenon-derived functionality manifests itself through the experimentally validated principles. First, our work achieves nonreciprocal microwave transmission through the synergistic breaking of time-reversal symmetry by gyromagnetic and Faraday effects, delivering an isolation ratio of 20 dB that meets the isolator standard. Notably, the isolation direction can be reversed by switching the magnetic field direction, which is a feature uncommon in conventional isolators. Moreover, in our USC regime, the isolation bandwidth exceeds 1.18 GHz with a coupling strength 5–70 times greater than that achievable in conventional strong coupling regimes, as shown in Fig. 5. As clearly evidenced in the comparative studies that meet the isolation standard, our work demonstrates significant superiority in coupling strength, coupling efficiency, and isolation bandwidth over existing approaches28,29,30,32,56.

It should be emphasized that while not yet a ready-made device, our framework establishes the fundamental physical basis for future isolators. Scaling down the PC cavity dimensions could shift operational frequencies to millimeter-wave bands (30–300 GHz). For instance, reducing the lattice constant from 20 mm to 2 mm would scale the defect mode frequency from 10 GHz to 100 GHz. Consequently, we can integrate the photonic crystal structure onto the circuit board to reduce the size, while maintaining the YIG defect size relative to wavelength. This aligns with 5G/6G applications, though challenges in miniaturization and magnetic field control require further study.

Discussion

In this work, we successfully achieved the simultaneous realization of NRC and USC in the YIG-PC system. We demonstrated a nonreciprocal microwave transmission within the photonic bandgap by the gyromagnetism and Faraday effect and realized the USC strength of 1.18 GHz and a coupling efficiency of 10.9%. The breaking of time-reversal symmetry, combined with the system’s asymmetric design, significantly enhanced the nonreciprocal behavior. Our experimental results, corroborated by theoretical and numerical analyses, confirm that the system operates in the USC regime, where the RWA becomes invalid.

Our work distinguishes itself from previous research by integrating NRC and USC within a single system, offering new insights into cavity magnonics. Furthermore, it lays the foundation for developing advanced nonreciprocal devices, such as isolators and circulators, in hybrid quantum systems. Unlike superconducting USC devices requiring cryogenic environments, our design operates at room temperature, significantly reducing implementation costs and complexity. By leveraging the broad interaction spectrum enabled by USC, we achieve a 20 dB isolation ratio over a 1.2 GHz isolation bandwidth, surpassing conventional YIG isolators constrained by narrowband ferromagnetic resonance. The nonreciprocity of direction and strength can be dynamically tuned by applied magnetic fields, a feature absent in static geometric isolators. Future works will focus on enhancing the coupling strength, improving the quality of microwave transmission, and advancing the miniaturization of principle-based devices.

Methods

Device description

As shown in Fig. 1a, a 2D chamber is constructed by two aluminum plates with 5 mm of separation and surrounded by some microwave absorbing materials. All of the cylinders, which have a diameter and a height as 5 mm are placed in the chamber and the lattice constant of the 2D simple cubic structure is defined as 20 mm. We choose a single crystal YIG as the magnetic material because of its low microwave magnetic-loss parameter and high-spin-density57. Our YIG has a saturation magnetization Ms = 1750 G, a gyromagnetic ratio γ = 2.8 MHz/Oe, and a linewidth of 10 Oe.

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

04 December 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00120-0

References

Mabuchi, H. & Doherty, A. C. Cavity quantum electrodynamics: coherence in context. Science 298, 1372–1377 (2002).

Forn-Díaz, P., Lamata, L., Rico, E., Kono, J. & Solano, E. Ultrastrong coupling regimes of light-matter interaction. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 025005 (2019).

Frisk Kockum, A., Miranowicz, A., De Liberato, S., Savasta, S. & Nori, F. Ultrastrong coupling between light and matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 1, 19–40 (2019).

Qin, W., Kockum, A. F., Muñoz, C. S., Miranowicz, A. & Nori, F. Quantum amplification and simulation of strong and ultrastrong coupling of light and matter. Phys. Rep. 1078, 1–59 (2024).

Niemczyk, T. et al. Circuit quantum electrodynamics in the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 6, 772–776 (2010).

Todorov, Y. et al. Ultrastrong light-matter coupling regime with polariton dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 196402 (2010).

Schwartz, T., Hutchison, J. A., Genet, C. & Ebbesen, T. W. Reversible switching of ultrastrong light-molecule coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 196405 (2011).

Sundaresan, N. M. et al. Beyond strong coupling in a multimode cavity. Phys. Rev. X 5, 021035 (2015).

Yoshihara, F. et al. Superconducting qubit–oscillator circuit beyond the ultrastrong-coupling regime. Nat. Phys. 13, 44–47 (2017).

Zhang, X., Zou, C.-L., Jiang, L. & Tang, H. X. Cavity magnomechanics. Sci. Adv. 2, e1501286 (2016).

Harder, M. & Hu, C.-M. Cavity spintronics: an early review of recent progress in the study of magnon-photon level repulsion. Solid State Phys. 69, 47–121 (2018).

Bhoi, B. & Kim, S.-K. Photon-magnon coupling: historical perspective, status, and future directions. Solid State Phys. 70, 1–77 (2019).

Hu, C.-M. The 2020 roadmap for spin cavitronics. Solid State Phys. 71, 117–121 (2020).

Zare Rameshti, B. et al. Cavity magnonics. Phys. Rep. 979, 1–61 (2022).

Soykal, Ö. O. & Flatté, M. E. Strong field interactions between a nanomagnet and a photonic cavity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 077202 (2010).

Soykal, Ö. O. & Flatté, M. E. Size dependence of strong coupling between nanomagnets and photonic cavities. Phys. Rev. B 82, 104413 (2010).

Huebl, H. et al. High cooperativity in coupled microwave resonator ferrimagnetic insulator hybrids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 127003 (2013).

Zhang, X., Zou, C.-L., Jiang, L. & Tang, H. X. Strongly coupled magnons and cavity microwave photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 156401 (2014).

Hou, J. T. & Liu, L. Strong coupling between microwave photons and nanomagnet magnons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 107702 (2019).

Harder, M. et al. Level attraction due to dissipative magnon-photon coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 137203 (2018).

Bhoi, B. et al. Abnormal anticrossing effect in photon-magnon coupling. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134426 (2019).

Bourcin, G., Gardin, A., Bourhill, J., Vlaminck, V. & Castel, V. Level attraction in a quasiclosed cavity: antiresonance in magnonic devices. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 064036 (2024).

Hyde, P., Bai, L., Harder, M., Match, C. & Hu, C. M. Indirect coupling between two cavity modes via ferromagnetic resonance. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 152405 (2016).

Bai, L. et al. Cavity mediated manipulation of distant spin currents using a cavity-magnon-polariton. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 217201 (2017).

Li, J., Zhu, S.-Y. & Agarwal, G. S. Magnon-photon-phonon entanglement in cavity magnomechanics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 203601 (2018).

Rao, J. et al. Meterscale strong coupling between magnons and photons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 106702 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Anomalous long-distance coherence in critically driven cavity magnonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 206902 (2024).

Wang, Y.-P. et al. Nonreciprocity and unidirectional invisibility in cavity magnonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 127202 (2019).

Zhang, C. et al. Nonreciprocal multimode and indirect couplings in cavity magnonics. Phys. Rev. B 103, 184427 (2021).

Shi, Y., Zhang, C., Jiang, C., Ong, C. K. & Chai, G. Mirror symmetric nonreciprocity and circular transmission in cavity magnonics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 132403 (2021).

Zhao, Y., Rao, J., Gui, Y., Wang, Y. & Hu, C.-M. Broadband nonreciprocity realized by locally controlling the magnon’s radiation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 014035 (2020).

Zhang, X., Galda, A., Han, X., Jin, D. & Vinokur, V. M. Broadband nonreciprocity enabled by strong coupling of magnons and microwave photons. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044039 (2020).

Kim, J., Kim, B., Kim, B., Jeon, H. & Kim, S.-K. Magnetic-field controlled on-off switchable non-reciprocal negative refractive index in non-hermitian photon-magnon hybrid systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 9014 (2024).

Goryachev, M. et al. High-cooperativity cavity QED with magnons at microwave frequencies. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2, 054002 (2014).

Bourhill, J., Kostylev, N., Goryachev, M., Creedon, D. L. & Tobar, M. E. Ultrahigh cooperativity interactions between magnons and resonant photons in a YIG sphere. Phys. Rev. B 93, 144420 (2016).

Everts, J. R. et al. Ultrastrong coupling between a microwave resonator and antiferromagnetic resonances of rare-earth ion spins. Phys. Rev. B 101, 214414 (2020).

Ghirri, A. et al. Ultrastrong magnon-photon coupling achieved by magnetic films in contact with superconducting resonators. Phys. Rev. Appl. 20, 024039 (2023).

Golovchanskiy, I. et al. Approaching deep-strong on-chip photon-to-magnon coupling. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 034029 (2021).

Golovchanskiy, I. A. et al. Ultrastrong photon-to-magnon coupling in multilayered heterostructures involving superconducting coherence via ferromagnetic layers. Sci. Adv. 7, eabe8638 (2021).

Bourcin, G., Bourhill, J., Vlaminck, V. & Castel, V. Strong to ultrastrong coherent coupling measurements in a YIG/cavity system at room temperature. Phys. Rev. B 107, 214423 (2023).

Zhang, C., Shi, Y., Zhang, W., Jiang, C. & Chai, G. Ultra-strong magnon-photon coupling induced in the photonic crystals with an YGaGeIG defect. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 022407 (2019).

Kittel, C. On the theory of ferromagnetic resonance absorption. Phys. Rev. 73, 155–161 (1948).

Chikazumi, S. Physics of Ferromagnetism. (Oxford University, 1997).

Joannopoulos, J. D., Johnson, S. G., Winn, J. N. & Meade, R. D. Photonic Crystals Molding the Flow of Light. (Princeton University Press, 2008).

Zhang, C. et al. Supplementary material for “simultaneous nonreciprocal and ultra-strong coupling in cavity magnonics". Available as part of the main paper (2025).

Poo, Y., Wu, R.-x, Lin, Z., Yang, Y. & Chan, C. T. Experimental realization of self-guiding unidirectional electromagnetic edge states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 093903 (2011).

So, P., Anlage, S. M., Ott, E. & Oerter, R. N. Wave chaos experiments with and without time reversal symmetry: GUE and GOE statistics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 2662–2665 (1995).

Dietz, B. et al. Induced violation of time-reversal invariance in the regime of weakly overlapping resonances. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 064101 (2009).

Dietz, B., Guhr, T., Harney, H. L. & Richter, A. Strength distributions and symmetry breaking in coupled microwave billiards. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 254101 (2006).

Dietz, B., Klaus, T., Miski-Oglu, M., Richter, A. & Wunderle, M. Partial time-reversal invariance violation in a flat, superconducting microwave cavity with the shape of a chaotic Africa billiard. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 174101 (2019).

Dietz, B. et al. Fullerene c60 simulated with a superconducting microwave resonator and test of the Atiyah-Singer index theorem. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 026801 (2015).

Walls, D. F. & Milburn, G. J. Quantum Optics (Springer, 2008).

Keller, J. et al. Landau polaritons in highly nonparabolic two-dimensional gases in the ultrastrong coupling regime. Phys. Rev. B 101, 075301 (2020).

Zare Rameshti, B., Cao, Y. & Bauer, G. E. W. Magnetic spheres in microwave cavities. Phys. Rev. B 91, 214430 (2015).

Krupka, J. et al. Resonances in large ferrimagnetic YIG samples-electrodynamic analysis. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 521, 167536 (2021).

Kim, M., Tabesh, A., Zegray, T., Barzanjeh, S. & Hu, C.-M. Nonreciprocity in cavity magnonics at millikelvin temperature. J. Appl. Phys. 135, 063904 (2024).

Serga, A. A., Chumak, A. V. & Hillebrands, B. YIG magnonics. J. Phys. D. 43, 264002 (2010).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Peng Yan, Prof. Jinwei Rao, and Dr. Weihua Zhang for useful discussions and suggestions. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Nos. 52471200, 12174165 and 52201219) and Scientific Research Innovation Capability Support Project for Young Faculty (ZYGXQNJSKYCXNLZCXM-l19).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.Z. and Z.H. fabricated the devices, conducted the experiment and analyzed the data. C.Z. prepared all figures and wrote the Results section. C.Z. and Y.S. contributed to building the model. X.L. and D.G. provided support and conceptual advice. C.Z. and C.J. devoted to simulation about microwave.C.Z. developed the theory in discussions with C.K.O. G.C. supervised the project and interpreted the results. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Hao, Z., Shi, Y. et al. Simultaneous realization of nonreciprocal and ultra-strong coupling in cavity magnonics. npj Spintronics 3, 45 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00110-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00110-2