Abstract

Topological defects play a crucial role across various fields, mediating phase transitions and macroscopic behaviors as they propagate through space. Their role as robust information carriers has also generated much attention. However, controlling their motion remains challenging, especially towards achieving motion along well-defined paths, which typically require predefined structural patterning. Here, we demonstrate the tunable, unidirectional motion of topological defects in a laterally unconfined thin film. The motion of these defects—specifically magnetic dislocations—is shown to mediate the overall continuous rotation of the stripe pattern in which they are embedded. We determine the connection between the unidirectional motion of dislocations and the underlying three-dimensional (3D) magnetic structure by performing 3D magnetic vectorial imaging with in situ magnetic fields. A minimal model for dislocations in stripe patterns that encodes the symmetry breaking induced by the external magnetic field reproduces the motion of dislocations that facilitate the 2D rotation of the stripes, highlighting the universality of the phenomenon. This work establishes a framework for studying the field-driven behavior of topological textures and designing materials that enable well-defined, controlled motion of defects in unconfined systems, paving the way to manipulate information carriers in higher-dimensional systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Topological defects1 are ubiquitous across various physical systems. From vortex–antivortex pairs in superconductors2 to dislocations in crystals3,4, topological defects emerge even in active matter5, where in contexts as biology, they are found to mediate fundamental processes such as tissue regeneration and cell death6. In magnetism, topological defects not only mediate processes that influence the macroscopic behavior of materials but, at the nanoscale, they can be used to carry information7, opening the door to fascinating fundamental physical phenomena and technological applications. Indeed, topological defects can be considered to have a double role: as mediators of processes as well as information carriers.

As mediators, topological defects can be studied as quasi-particles that can be created and destroyed, and that move through space8. For instance, controlling the creation of structural dislocations can enhance the performance of non-rare-earth permanent magnets9 used in technology and energy generation. Another example is magnetic dislocations in helimagnets, which facilitate skyrmion and bubble nucleation under a magnetic field, mediating the transition between stripe and skyrmionic phases10. To control these mediated processes, it is crucial to understand how topological defects respond to external excitations, such as magnetic fields or electric currents.

On the other hand, as information carriers, topological defects have attracted recent attention since they can be propagated and controlled, and represent an energy-efficient alternative to conventional computing devices. For instance, in magnetic racetracks, information is carried by domain walls as they move along a patterned nanostrip7. This one dimensional (1D) motion is achieved by the geometric confinement of the track, enabling precise control over the transfer of information from one point to another. Going beyond confined systems promises higher complexity, density, and reconfigurability needed for non-traditional computing and logic devices11. However, achieving such controlled motion of defects in unconfined systems can be more challenging. In the case of skyrmions, for instance, it requires the cancellation of the skyrmion Hall effect to move in straight lines within two-dimensional (2D) planes12,13. Indeed, when realizing topological defects as information carriers, the main challenge resides in achieving precise control over their motion, raising the question of whether the 1D motion of defects in an unconfined system is possible. Recently, unidirectional motion of defects has been achieved without the need for nanopatterning of materials, but rather by promoting the “gliding” of defects along the direction of straight stripe domain patterns14,15. Although in those cases, the motion is restricted to the stripe direction, this prospect of achieving controllable, unidirectional motion in unconfined systems offers new possibilities for future information transport devices.

Here, we present a laterally unconfined system where topological defects exhibit a well-defined lateral 1D motion, the direction of which can be chosen within the two dimensional plane, mediating a continuous transition of the system order parameter. The system consists of a magnetic thin film hosting weak stripe domains that rotate continuously when subjected to an external in-plane magnetic field. Intriguingly, the 1D motion is not confined to the direction of the stripe background but occurs in the 2D plane of the system and it is defined by the combination of the stripe orientation and the magnetic field. We demonstrate that the continuous behavior of the rotation transition is enabled by topological defects, specifically magnetic dislocations, which propagate in a well-defined 1D direction despite the unconfined nature of the film. The direction of motion of these defects can be controlled using a magnetic field, opening the possibility to propagate defects along arbitrary paths in 2D planes. To determine the mechanism behind the motion of the dislocations, we perform high-resolution magnetic imaging with synchrotron X-rays, revealing the multidimensional nature of the system: the 1D motion of the magnetic defects mediates a 2D rotation process, that relies on the underlying three dimensional (3D) magnetic structure. Furthermore, we reproduce the unidirectional motion of defects driving the rotation transition using a minimal model that generally describes an ordered stripe pattern containing defects. This minimal model is relevant beyond magnetism, thus highlighting the universality of this phenomenon. Altogether, the understanding gained with this multidimensional approach opens the door to the design of controlled motion of topological defects within unconfined systems.

Results

Role of dislocations in the rotation process

To investigate topological defects as mediators of processes, we select a model system exhibiting a spontaneous symmetry breaking resulting in a stripe pattern. Such a stripe pattern can be found in various contexts, including surface wrinkles16, diblock copolymers17 and magnetic domain configurations (see Fig. 1a). In all of these systems, defects known as dislocations occur when stripes bifurcate into two branches (Fig. 1b). Here we focus on weak magnetic stripes, where elongated domains of canted out-of-plane magnetization form, with a net in-plane magnetic moment. When imaging the magnetic stripe pattern, we find more than one hundred dislocations in the 15 × 15 μm2 field of view, highlighted with yellow dots in Fig. 1a, making this an ideal system to study the motion of topological defects, and how they influence magnetic behavior.

a,c,d The projection of the out-of-plane magnetization mz in a 400 nm-thick Py film is imaged across a 15 × 15 μm2 field of view by scanning transmission X-ray microscopy. The average orientation of the stripes α (blue arrow) rotates as an external magnetic field B (black arrow) is applied perpendicular to the initial orientation of the stripes. Scale bar represents 2.5 μm. b Magnetic dislocations appear when the stripes bifurcate into a left (L) and a right (R) branch. More than a hundred magnetic dislocations (yellow dots) are present in the system (a). e The average orientation of the stripes α increases continuously with the field B. f Comparison between the derivative of the angle of the stripes α with respect to the magnetic field B (blue stars)—i.e., the rate of rotation—and the number of dislocations (red dots). The peak ∂α/∂B matches the maximum in the number of dislocations, suggesting a connection between the rotation and the defects.

This system not only exhibits a high density of defects but also allows the manipulation of the stripes’ orientation through an external in-plane field, a property observed in several magnetic materials18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 known as rotatable anisotropy27,28. To visualize the weak stripe pattern, we probe the out-of-plane magnetization component in a 400 nm-thick permalloy (Py) film using scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM) with X-ray magnetic circular dichroism. The sample is prepared by initially applying a saturating vertical (y) magnetic field that aligns the stripes vertically. Subsequently, we apply a horizontal (x) magnetic field B at 90° to the stripe direction, causing the stripes to rotate, as demonstrated in Fig. 1c, d. The magnitude of the field is slowly increased step wise, and an image of the magnetic configuration taken for each field value. Each image is captured at equilibrium on the order of seconds, allowing us to study the evolution of the magnetic pattern in a quasi-static manner. As the magnetic field B increases, we observe a continuous transition in the average stripe orientation α (see Fig. 1e). Notably, since the orientation of the stripes remains stable at remanence, the continuous character in the transition suggests that non-volatile analog information could be potentially encoded in α.

A correlation between the rotation of the stripes and the behavior of dislocations is observed when comparing the derivative of the angle of the stripes α with respect to the magnetic field B (blue) to the number of dislocations (red). This effectively compares the rate of rotation to the dislocation population, as shown in Fig. 1f. The number of dislocations indeed does not remain constant with field but rather increases to a maximum before decreasing again, indicating that dislocations are created and annihilated during the rotation process. Notably, both the number of dislocations and the rate of rotation peak at the same field, meaning that the stripes rotate at a higher rate when the number of dislocations is higher. When we consider the rate of rotation, we can identify two regimes: below B < 21.1 mT, as the dislocations are created, the rotation rate increases, which is translated into a steeper slope for α vs B, while above B > 21.1 mT the predominant annihilation of defects reduces the rotation rate, resulting in a lower slope (see Fig. 1e, and Supplementary Fig. 1).

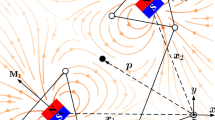

To delve deeper into the role of defects in the rotation process, we highlight changes in the stripe configuration by subtracting images measured at two consecutive fields, as shown in Fig. 2a. The resulting difference image exhibits zero contrast except along alternating black and white lines that are predominantly oriented in one direction. The orientation of these lines, plotted against the applied field in Fig. 2b, averages a constant −50° ± 4° relative to the initial stripe orientation at lower fields and then increases to −30° ± 4° at higher fields. Performing the experiment for different in-plane orientations yields consistent angular behavior, indicating that the system is isotropic. Remarkably, these lines are not aligned with the average orientation of the stripes, and therefore indicate the presence of 1D phenomena occurring within the unconfined 2D plane of the system. The lines are narrower and better defined at lower fields, and become less well defined at higher fields, indicating the presence of multiple regimes of the phenomenon (see Supplementary Figs. 2–5 for all difference images).

a The path taken by the defects can be detected by subtracting two images of consecutive field steps. b The average orientation of these lines is approximately constant for fields below 21.1 mT (gray vertical line) regardless of the average orientation of the stripes, and increases from −50(4)° to −30(4) ° for higher fields. Four different types of events are identified: c A dislocation with its two branches extending down moves diagonally with the horizontal component of its motion parallel to the magnetic field, acting as a positive particle. d A dislocation with its two branches extending up moves diagonally with the horizontal component of its motion antiparallel to the magnetic field, acting as a negative particle. e A pair of positive and negative dislocations are created. f A pair of positive and negative particles annihilate each other.

To understand the origin of these lines, we compare the two magnetic configurations in the vicinity of the lines. For line 1 (green box in Fig. 2a), a dislocation (shaded in red in Fig. 2c) moves diagonally from one end of the line to the other, with the horizontal component of its motion parallel to the magnetic field, acting as a “positive” particle. In contrast, for line 2 (red box), a dislocation (shaded in blue in Fig. 2d) moves in the opposite direction, hence behaving as a “negative” particle. Dislocations behave as positive or negative particles depending on the direction of the bifurcation, regardless of their net out-of-plane magnetization (black or white contrast). Such behavior was observed for all dislocations imaged during the rotation transition, as shown in detail in Supplementary Figures 2–5. They exhibit indeed a well-defined 1D motion, as suggested by the difference images. Remarkably, the motion orientation is not solely defined by the orientation of the stripes, but instead by the combination of the field direction with respect to the stripes, as seen in Fig. 2b where the direction of motion is constant despite the changing orientation of the stripes. Indeed, as shown in Supplementary Figures 6 and 7, even when one simply reverses the sign of the applied field, the defects are not propagated in the opposite direction, but in a different, well defined direction defined by the relative orientation of the in plane component of the magnetization and the reversed magnetic field. This property would allow one to propagate the defects along different directions with respect to the stripe orientation, opening the possibility to propagate defects along arbitrary paths in 2D planes controlled by external stimuli.

The alternating contrast in these difference images indicates that dislocations oscillate between black and white states, requiring one branch to break for a dislocation to switch states and therefore move. This diagonal motion combines a parallel (climbing) and perpendicular (gliding/slipping) movement with respect to the stripes. Such motion combining climbing and gliding has previously been observed occurring stochastically in magnetic materials8,29, and represents a universal mechanism for dislocations in general to move in different directions3. However, this is the first time that such combined motion has been observed following a deterministic well-defined 1D trajectory while mediating a continuous process such as the rotation of the stripes.

As well as observing the motion of dislocations in the system, we also find that these dislocations, akin to charged particles, are also created and annihilated in pairs. For instance, in Fig. 2e, a pair of positive and negative defects emerges from a previously uniform stripe phase when the field increases, while in Fig. 2f, a pair annihilates in the next field step. These observations demonstrate that the dislocations undergo processes of creation, annihilation and propagation during the rotation of the stripes, thus exhibiting particle/ antiparticle behavior.

To determine how the movement of defects relates to the overall rotation of the stripes, we examine the local orientation of the stripes in the vicinity of the propagation lines. In Fig. 2c, the area within the dashed-green frame is notably the only region where the stripes have rotated with respect to the previous orientation. This behavior is consistent across other propagation lines, indicating that dislocation movement drives local stripe rotation, leading to a continuous global reorientation. This mechanism resembles that of dislocation motion known in crystals where the motion of dislocations promotes the local reorientation of the crystal lattice30.

Dislocations are crucial mediators in the rotation process, moving in a well-defined direction even without geometric constraints, particularly in the lower field regime. Their unidirectional motion in a two-dimensional system suggests potential as information carriers. However, understanding the underlying mechanism behind this unidirectional movement is essential to harness this phenomenon.

Effect of the 3D magnetic configuration

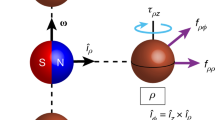

To determine the underlying mechanism for the movement of the dislocations, we consider the multidimensional nature of the system. While in the previous section only the out-of-plane magnetization component was probed, the stripe domains exhibit a more complex 3D magnetic structure26. To determine this 3D configuration under the application of magnetic fields, we perform X-ray magnetic laminography31,32, as illustrated in Fig. 3a, to obtain full 3D vectorial reconstructions of the magnetization configuration of the sample (Fig. 3b). While 3D X-ray magnetic imaging is now well established33,34,35,36, the incorporation of external stimuli is challenging due to the fact that the environment must rotate with the sample. Previous studies demonstrate dynamic imaging of the magnetic response to weak magnetic fields31, while insight into the 3D morphology of skyrmion strings under fields has been gained with scalar 3D imaging of a single magnetic component37. However, tracking the 3D vectorial configuration under the application of larger magnetic fields has not been possible. Here, we develop a dedicated sample holder (Fig. 3a) with which we can combine X-ray magnetic laminography with in situ magnetic fields to follow the evolution of the 3D configuration of the stripes and defects.

a Circularly polarized X-rays are focused on the sample surface which is tilted at 45° with respect to the beam, and the transmitted light is measured by a photodiode. The sample is moved in the direction of the green arrows to perform scanning transmission X-ray microscopy (STXM). By rotating the sample around the laminography axis, which corresponds to the surface normal of the sample, a set of 2D STXM images is obtained that can be used to reconstruct the 3D vectorial magnetization. To measure laminography while applying in situ magnetic fields, a special sample holder with stacking permanent magnets is used. This design ensures that the magnetic field follows the sample as it rotates, maintaining the same magnetic configuration during the laminography measurement. b As a result of the laminography measurement, a 3D vectorial magnetic image is obtained showing the magnetic configuration in a 5 μm-diameter cylindrical field of view of the sample. Three holes are milled into the sample to facilitate normalization of the illumination and alignment of the image set.

The 3D magnetic configuration of the stripes at zero field, shown in Fig. 4a, b, reveals out-of-plane domains (red and blue) and vortex-like domain walls with a core that points along the direction of the domain wall, known as Bloch cores. These Bloch cores are all oriented in the same direction (as seen by the my component in Fig. 4a), resulting in a net in-plane magnetization, consistent with macroscopic magnetometry measurements27 (see hysteresis loop in Supplementary Fig. 8). As a magnetic field perpendicular to the initial stripe orientation is applied, this in-plane magnetization prefers to align with the field to reduce the Zeeman energy. This breaks the symmetry between the rotation of the stripes clockwise and counterclockwise, promoting a counter clockwise rotation as seen in our experimental 2D images.

Top views (a,c,g) show in red-blue contrast the out-of-plane magnetization mz in a section through the middle of the sample, and the full vector field in the Bloch cores. The Bloch cores are estimated as isosurfaces of higher vorticity with respect to the rest of the magnetic structure (gray tubes). These tubes appear as white circles in the cross sections (b,d). When a magnetic field B = 16 mT is applied, the stripes rotate. The in-plane magnetization also rotates and, as a result, an envelope of magnetization (pink streamlines) passing over and under the Bloch cores is formed, expelling the Bloch cores towards the surface of the sample. Near the dislocations (e), the upper illustration shows the in-plane magnetization in the domain walls of a dislocation. The cut on the right (R) is facilitated by the envelope as illustrated in (f). The lower illustration in (e) represents the final state after the branch R is cut, resulting in the dislocation (shaded in blue) moving upwards. g The experimental configuration confirms the presence of the envelope in the right branch.

When the 3D configuration under the application of field is mapped in Fig. 4c, d, we observe that the field shifts the cores of the domain walls towards the surface, as predicted in22,23, resulting in a net undulating flow of the magnetization in the direction of the field that is not present at zero field, referred to here as the “envelope” (dark-pink streamlines).

To understand the effect of this change in the 3D magnetic configuration on the movement of the defects, we consider the magnetization in the domain walls in the vicinity of a negative dislocation, as shown in Fig. 4e. Here the magnetization of the domain walls in the dislocation’s right branch is less aligned to the magnetic field than that of the left branch, meaning that the right branch has higher energy than the left one. In order for the dislocation to move, one of the branches must break which, due to its higher energy, is more likely to be the right branch. This would result in the upward-branching dislocation moving in the opposite direction of the field, akin to a negatively charged particle, as observed in Fig. 2d. Conversely, downward-branching dislocations move towards the direction of the field, resembling positively charged particles.

Having determined the cause of the sense of rotation of the stripes and the sense of propagation of the dislocations, we next delve deeper into the underlying mechanism of their motion, specifically focusing on the breaking of the branch. We consider the right branch and take a cross section near the core (orange line in Fig. 4e). In Fig. 4f, we represent schematically the magnetic structure of this cross section and illustrate how the closure domains, Bloch cores, and the envelope may evolve as the field increases. At zero field B = 0 (1), up and down magnetic domains are separated by Bloch cores (black circles). As B increases, the global state becomes energetically unfavorable, leading the magnetization to begin to align along the field (2). Consequently, the magnetization locally rotates into the plane forming an envelope (pink line) that pushes the Bloch cores toward the surface. With higher fields, the magnetization aligns more strongly with the field, straightening the envelope as if it were a rope (3). While this phenomenon occurs globally, in the vicinity of the dislocations, the in-plane tilting acts to expel two domain walls and merge the domains, as shown in Fig. 4e, effectively breaking the branch and shifting the dislocation. This behavior is confirmed by the mapping of the 3D magnetization field in the vicinity of the dislocation, where we indeed observe an envelope forming across the right branch of a negative dislocation shown in Fig. 4g, as in Fig. 4f(2) (see more details on the magnetic structure of the branches in Supplementary Fig. 9). This effectively guides the dislocation motion and facilitates the rotation of the stripes. By visualizing the 3D configuration, we gain a deeper understanding of the rotation of the stripes and the motion of the defects, highlighting the multidimensional nature of the system. Specifically, the underlying 3D structure and its response to magnetic fields reveals the mechanism of motion of dislocations and their charged-particle nature.

Modeling defect motion and stripe rotation

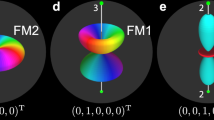

Having understood the 3D mechanism by which dislocations move, we now focus on the universality of this phenomenon. Specifically, we consider a minimal approach based on the Swift-Hohenberg (SH) model38—or non-conservative phase field crystal (PFC) model39,40—supporting the modeling of stripe phases and dislocations. This approach builds on a free energy density

where the smooth order parameter ψ ≡ ψ(r) mimics the out-of-plane magnetization component mz. The parameter ϵ is a phenomenological temperature parameter that governs the phase minimizing the free energy. Specifically, it controls the transition between an ordered phase (ϵ > 0), characterized by a periodic ψ, and a disordered phase (ϵ < 0) where ψ remains constant. Here, it is set to 0.5 to represent fully out-of-plane magnetization, typical of magnetic systems with perpendicular anisotropy, in an ordered phase. The last term of Eq. (1) promotes the formation of stripes with a periodicity of 2π/q040, as shown in Fig. 5a (see Methods for more details).

a Stripe pattern described by ψ as minimizer of the free energy, representing the out-of-plane magnetization. b The term ∣ ∇ψ∣2 mimics the domain walls. c To account for the in-plane magnetization min-plane, we introduce the vector τ. d A setting featuring the deviation of τ from the direction of (unperturbed) stripes due to the action of the magnetic field B. e Introducing a pair of positive (red) and negative (blue) dislocations disrupts the ideal stripe ordering. f The external field induces motion of the defects, which also allows for rotation of stripes (see shaded red regions). g Adding more dislocations reveals a difference image similar to the experiments where the lines correspond to dislocation paths.

Although the SH model successfully leads to the presence of stripe phases reminiscent of our weak magnetic stripes, to model the magnetic field induced motion of the stripes, we introduce further terms into the free energy that consider the net in-plane direction of the domain walls. Specifically, we introduce the unit vector \({\boldsymbol{\tau }}\equiv {\boldsymbol{\tau }}(\theta )=[-\sin (\theta ),\cos (\theta )]\) with θ an additional model variable that represents the direction of the in-plane magnetization. This direction is modulated by ∣ ∇ψ∣2 to reflect the enhanced in-plane magnetization in the domain walls (see Fig. 5b, c). Our model is then described by the free energy F[ψ, θ] = ∫Ωfdr with

The second term mimics the Zeeman energy and is minimized when ∣ ∇ψ∣2τ is parallel to the magnetic field B. The third term promotes the Bloch-type nature of the domain walls, coupling τ to the direction parallel to the stripes (perpendicular to ∇ψ). The last term avoids sharp gradients in the orientation of τ, similar to an exchange energy within the domain wall. Similar terms in PFC models have been previously introduced to investigate the influence of the underlying crystallographic microstructure on magnetic ordering and responses in materials41,42,43. Here, to model the rotation of the stripe phase in response to an external magnetic field, we retain the minimal energy terms to directly describe (magnetic) stripes, and focus on the role of magnetic dislocations. To enable the dynamic relaxation of our system, modeled by ψ and τ, we evaluate non-conservative coupled gradient flow equations, as described in the Methods.

In the absence of an external magnetic field (B = 0), the Bloch-type wall energy terms enforce the in-plane magnetization modeled by τ to be aligned with the stripes, which are perpendicular to ∇ψ (see Fig. 5a–c). When increasing B, the Zeeman energy would favor the alignment of the in-plane magnetization to B, consequently favoring the alignment of the stripes themselves to B. We find, however, that the absence of perturbations in the system hinders the rotation of stripes, with τ rotating away from the domain wall direction as shown in Fig. 5d.

The importance of defects in mediating the rotation of the stripes becomes clear when they are introduced into our minimal model. The pair of positive and negative dislocations shown in Fig. 5e create perturbations in the orientation of the stripes. These perturbations result in a symmetry breaking when an external field B is applied, which leads to the motion of the defects, as shown in Fig. 5f, and causes the stripes to rotate as the dislocations move. The positive (negative) dislocation moves to the left (right), in the (opposite) direction of B, resulting in the counterclockwise rotation of the stripes, as observed in our 2D experiments (Fig. 2c, d). This movement of the dislocations enables the alignment of the in-plane component with B, as observed in the 3D experiments (Fig. 4c, d).

Having determined that defects facilitate the rotation of the stripes, we next consider a system with a higher number of defects, as in the experiments, and we calculate the difference image between consecutive configurations, as shown in Fig. 5g. This image reveals clear paths of unidirectional motion for the dislocations as observed experimentally. It is worth noting that in our simulations, dislocations can move indefinitely over time (or until they annihilate with another dislocation), since they lack any arresting force provided, for example, by quenched disorder44. In contrast, in our experiments the dislocations stop at seemingly random positions due to pinning in the sample, leading to finite paths that we measure in our quasi-static measurements, as shown in Fig. 2a. The unidirectional movement of the dislocations is observed in both (quasi-static) experiments and (dynamic) simulations, suggesting that pinning does not play a significant role in the motion direction.

When comparing Fig. 5g to Fig. 2a, we also observe a slight difference in the angle of the 1D motion with respect to the experiments which may be ascribed to the more complex 3D magnetic configuration that is not considered in the model. Indeed, the model considers only the simple 2D configuration, meaning that the observed results—the 1D motion, dislocation-mediated stripe rotation and the charged particle behavior—are not limited to our magnetic stripe system, but can be considered in the context of a much wider variety of stripe-hosting systems.

The order parameter ψ and the vector field τ can represent different physical quantities depending on the system, such as the amplitude of out-of-plane deformation in wrinkled elastic bilayers16, or local concentration differences in diblock copolymers17. While fSH stabilizes a stripe pattern, the additional terms in the free energy density provide a minimal and general mechanism for coupling the stripe order to a preferential orientation set by, for example, an external magnetic field, or anisotropic strain.

With analogous phenomena in surface wrinkles16, polymer assembly17,45, and grain rotation in polycrystalline materials30,46, the motion of defects mediating continuous transitions plays an important role in the physics of a number of systems. By being able to reproduce the 1D motion of charged particles within a magnetic system with a minimal model, this work paves the way to a universal understanding of dislocation motion in striped systems influenced by in-plane fields, and their manipulation leveraging simple coupling effects. This understanding will inform a number of phenomena, from mechanical properties of materials, to the self assembly of polymers, as well as information-carrying defects in magnetic systems.

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrate the unidirectional propagation of topological defects in a laterally unconfined system that mediates a continuous transition of the order parameter, where the defects can be propagated in different directions in a 2D plane. Using a comprehensive approach that combines 2D and 3D X-ray magnetic imaging with phenomenological modeling, we reveal that the motion of magnetic dislocations is multidimensional: their one-dimensional movement facilitates a two-dimensional rotation of magnetic stripes, driven by the three-dimensional magnetic configuration.

Our results show that magnetic dislocations rotate the stripes locally as they move, enabling the system to gradually adjust its average orientation in response to an external magnetic field. We find that the in-plane magnetization, characteristic of weak magnetic stripes, dictates the positive or negative charge behavior of the dislocations. This robust motion, reproducible in a simple phenomenological model, enhances our understanding of topological defects in unconfined systems and opens avenues for controlled defect motion beyond nanostructured materials.

From a technical standpoint, we establish field-dependent X-ray magnetic laminography by developing a dedicated sample holder with stackable permanent magnets, which allows for a tunable magnetic field, up to 100 mT in magnitude, and full vectorial reconstruction without disrupting the magnetic configuration. This capability opens new possibilities to study the field-driven evolution of magnetic configurations, to explore a broader range of materials and phenomena.

Regarding the behavior of our model system, here we highlight the ability to stabilize and manipulate the orientation of magnetic stripes. The dense presence of magnetic defects allows for a smooth transition in stripe orientation from 0 to 90°. Previous studies have demonstrated such analog behavior in helimagnets, also known as helitronics47. However, in that case, the helical stripes are limited to vertical or horizontal orientations, meaning that analog values between 0 and 1 are obtained from the percentage of vertical stripes compared to horizontal stripes. In contrast, in our system the angle of the stripe orientation can be treated as a continuous, analog quantity. Notably, upon removal of the external magnetic field, the orientation of the stripes remains stable, enabling the encoding of non-volatile analog information, potentially relevant for neuromorphic computing48,49.

Lastly, we note that the behavior of the magnetic dislocations in this system resembles that of fractons, pseudo-particles that move in 1D within a 2D system. This controlled 1D motion in Py thin films offers a platform to explore fractionalized excitations and their restricted mobility in a well established magnetic system. Key to exploiting this behavior will be the manipulation of dislocation propagation angles, which may be achieved by inducing specific perpendicular magnetic anisotropy through tuning the film’s growth parameters. The realization of such unidirectional behavior of topological defects paves the way for further exploration into the intriguing dynamics and applications of fractons within quantum condensed matter systems, from purely magnetic systems, to superconductors and heterostructures.

Methods

Sample preparation

Permalloy (Py) films were grown at room temperature in an ultra-high vacuum magnetron sputtering deposition system, which was evacuated to a base pressure lower than 5 × 10−9 mbar prior to the growth. For the growth of Py, the partial pressure of Argon gas was set specifically to 9 × 10−3 mbar, to promote the magnetic stripe order of Py not achievable at lower Ar working pressure. The target-to-substrate distance was fixed to 20 cm, and the substrate rotated at 24 rpm to ensure a spatially homogeneous sample thickness and composition. We used a 7.62 cm in diameter Ni81Fe19 target, in a face-to-face geometry, and applied a continuous (DC) source power of 40 W, corresponding to a deposition rate of 0.47 Å s−1. The films were capped in situ by 4 nm of Au, sourcing 20 W DC power to a 5.08 cm in diameter target, at a working pressure of 3 × 10−3 mbar of Ar, corresponding to a deposition rate of 1.33 Å s−1.

STXM and laminography

The SXTM and laminography experiments were performed at the PolLux (X07DA) endstation of the Swiss Light Source. The photon energy was tuned to 722.4 eV, which corresponded to the maximum X-ray magnetic circular dichroism signal at the Fe L2 edge.

We acquired 30 projections around the laminography axis, which in turn was tilted 45° with respect to the X-ray beam direction. The sample was rotated by a regular angular step of 12° around the 360°. Each projection image was measured with 3 ms of exposure time in a field of view of 10 × 10 μm2 with 250 × 250 points, giving a pixel size of 40 nm.

A special sample holder was designed for the in situ application of the external magnetic field during the laminography measurement. This sample holder has space at both sides of the sample for stacking a number of small permanent magnets. The size of each magnet is 1 × 1 × 5 mm3 and they create an in-plane magnetic field in the center of the sample holder of approximately 5 mT each. We calibrated the intensity of the field without the sample with a Hall probe before starting the experiment. Since they are embedded in the sample holder and they do not protrude, they do not interfere with the beam nor any other part of the experimental setup.

Minimal model

The model presented in the main text results in two dynamical equations, corresponding to non-conservative gradient flows for ψ and θ

with \({\bf{n}}\equiv {\bf{n}}(\theta )={\boldsymbol{\tau }}{(\theta )}^{{\prime} }\). These equations can be numerically solved by a standard Fourier pseudo-spectral method. By rewriting the equation above as \({\partial }_{t}\psi ={\mathcal{L}}\psi +{\mathcal{N}}(\psi )\) with \({\mathcal{L}}\) and \({\mathcal{N}}\) the linear and nonlinear operators, we solve for \({\partial }_{t}\widehat{\psi }={\widehat{{\mathcal{L}}}}_{k}{[\widehat{\psi }]}_{k}+{\widehat{{\mathcal{N}}}}_{k}\) with \({[\widehat{\psi }]}_{k}\) the coefficient of the Fourier transform of ψ, \({\widehat{N}}_{k}\) the Fourier transform of N(ψ) and \({\widehat{L}}_{k}\) the Fourier transform of \({\mathcal{L}}\) resulting in an algebraic expression of the wave vector. The solution at t + Δt, with Δt the time step, is then obtained via an inverse Fourier transform of \({[{\widehat{\psi }}_{n}]}_{k}(t+\Delta t)\) computed by the following approximation

Solutions ψ(t) are obtained by an inverse Fourier transform of \({[{\widehat{\psi }}_{n}]}_{k}(t)\). We note that this method naturally enforces periodic boundary conditions.

The parameters selected for the simulations reported in Fig. 5 are the following: q0 = 1, ϵ = 0.5, κ = 1, γ = 2, σ = 0.1, and B = 0.5, with the time and spacial discretizations Δt = 0.1 and Δx = 1.25, respectively.

An unperturbed stripe phase can be initialized by \(\psi =\bar{\psi }+\eta {e}^{i{\bf{k}}\cdot {\bf{r}}}+{\eta }^{* }{e}^{-i{\bf{k}}\cdot {\bf{r}}}\) with k the principal wave vector, \(\bar{\psi }\) the mean of ψ, and η amplitudes. To consider vertical stripes, as observed in the experiments, we initially set \({\bf{k}}=\left[{q}_{0},0\right]\), and (real) amplitudes η = η0 and \({\eta }_{0}=(2/3)\sqrt{3\epsilon -9{\bar{\psi }}^{2}}\) minimizing the energy for B = 0 (we set here \(\bar{\psi }=0\)). We note that non-zero external fields slightly vary the equilibrium wave number; however, this effect does not affect the evidence discussed above.

A smooth field ψ hosting dislocations can then be initialized by imposing (complex) amplitudes \(\eta ={\eta }_{0}{e}^{-i{\bf{k}}\cdot {{\bf{u}}}^{{\rm{dislo}}}}\) with udislo the displacement field induced by a dislocation50. Defects may also be obtained by considering an initial perturbation of stripes or by letting the stripe phase nucleate from random noise. However, setting the displacement of a chosen distribution of defects allows us to control the number and position of the defects and design specific configurations such as the idealized dipole as in Fig. 2e, without loss of generality. For a dislocation in 2D with Burgers vector aligned along the x-direction with length b it reads

In all simulations, τ is initialized to be parallel to the relaxed stripes. Dislocations are initialized with b = ± 2π. ν, namely the Poisson ratio, is set to 1/3 although the elastic constant encoded in the energy functional is then obtained when relaxing the initial condition via the gradient flow (3).

Data Availability

All data associated with this manuscript is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17351258.

References

Mermin, N. D. The topological theory of defects in ordered media. Rev. Mod. Phys. 51, 591 (1979).

Langer, J. S. & Ambegaokar, V. Intrinsic resistive transition in narrow superconducting channels. Phys. Rev. 164, 498 (1967).

Anderson, P., Hirth, J. & Lothe, J.Theory of Dislocations (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Harrison, C. et al. Mechanisms of ordering in striped patterns. Science 290, 1558–1560 (2000).

Shankar, S., Souslov, A., Bowick, M. J., Marchetti, M. C. & Vitelli, V. Topological active matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 380–398 (2022).

Ardaševa, A. & Doostmohammadi, A. Topological defects in biological matter. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 354–356 (2022).

Parkin, S. S., Hayashi, M. & Thomas, L. Magnetic domain-wall racetrack memory. Science 320, 190–194 (2008).

Dussaux, A. et al. Local dynamics of topological magnetic defects in the itinerant helimagnet fege. Nat. Commun. 7, 12430 (2016).

Jia, Y. et al. L 1 0 rare-earth-free permanent magnets: The effects of twinning versus dislocations in mn-al magnets. Phys. Rev. Mater. 4, 094402 (2020).

Yu, X. et al. Magnetic stripes and skyrmions with helicity reversals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 8856–8860 (2012).

Raab, K. et al. Brownian reservoir computing realized using geometrically confined skyrmion dynamics. Nat. Commun. 13, 6982 (2022).

Litzius, K. et al. Skyrmion hall effect revealed by direct time-resolved x-ray microscopy. Nat. Phys. 13, 170–175 (2017).

Jiang, W. et al. Direct observation of the skyrmion hall effect. Nat. Phys. 13, 162–169 (2017).

Hierro-Rodriguez, A. et al. Deterministic propagation of vortex-antivortex pairs in magnetic trilayers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 262402 (2017).

Fernández, V. V. et al. Memory effects on the current-induced propagation of spin textures in NdCo5/Ni8Fe2 bilayers. Phys. Rev. Applied 23, 014023 (2025).

Ohzono, T. & Shimomura, M. Defect-mediated stripe reordering in wrinkles upon gradual changes in compression direction. Phys. Rev. E: Stat., Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 73, 040601 (2006).

Hur, S.-M., Thapar, V., Ramírez-Hernández, A., Nealey, P. F. & de Pablo, J. J. Defect annihilation pathways in directed assembly of lamellar block copolymer thin films. ACS Nano. 12, 9974–9981 (2018).

Saito, N., Fujiwara, H. & Sugita, Y. A new type of magnetic domain in thin Ni–Fe films. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 19, 421–422 (1964).

Tee Soh, W., Phuoc, N. N., Tan, C. & Ong, C. Magnetization dynamics in permalloy films with stripe domains. J. Appl. Phys. 114, 053908 (2013).

Barturen, M. et al. Crossover to striped magnetic domains in Fe1−xGax magnetostrictive thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 092404 (2012).

Lehrer, S. S. Rotatable anisotropy in negative magnetostriction Ni–Fe films. J. Appl. Phys. 34, 1207–1208 (1963).

Tacchi, S. et al. Rotatable magnetic anisotropy in a Fe0.8Ga0.2 thin film with stripe domains: dynamics versus statics. Phys. Rev. B. 89, 024411 (2014).

Fin, S. et al. In-plane rotation of magnetic stripe domains in Fe1−xGax thin films. Phys. Rev. B. 92, 224411 (2015).

Coísson, M., Barrera, G., Celegato, F. & Tiberto, P. Rotatable magnetic anisotropy in Fe78Si9B13 thin films displaying stripe domains. Appl. Surf. Sci. 476, 402–411 (2019).

Leva, E. S. et al. Magnetic domain crossover in FePt thin films. Phys. Rev. B. 82, 144410 (2010).

Hierro-Rodriguez, A. et al. Revealing 3D magnetization of thin films with soft X-ray tomography: magnetic singularities and topological charges. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020).

Prosen, R., Holmen, J. & Gran, B. Rotatable anisotropy in thin permalloy films. J. Appl. Phys. 32, S91–S92 (1961).

Lommel, J. & Graham Jr, C. Rotatable anisotropy in composite films. J. Appl. Phys. 33, 1160–1161 (1962).

Pamyatnykh, L., Filippov, B., Agafonov, L. & Lysov, M. Motion and interaction of magnetic dislocations in alternating magnetic field. Sci. Rep. 7, 18084 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Grain rotation mediated by grain boundary dislocations in nanocrystalline platinum. Nat. Commun. 5, 4402 (2014).

Donnelly, C. et al. Time-resolved imaging of three-dimensional nanoscale magnetization dynamics. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 356–360 (2020).

Witte, K. et al. From 2D STXM to 3D imaging: soft x-ray laminography of thin specimens. Nano Lett. 20, 1305–1314 (2020).

Donnelly, C. et al. Three-dimensional magnetization structures revealed with x-ray vector nanotomography. Nature 547, 328–331 (2017).

Hierro-Rodriguez, A. et al. 3d reconstruction of magnetization from dichroic soft x-ray transmission tomography. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 25, 1144–1152 (2018).

Di Pietro Martínez, M. et al. Three-dimensional tomographic imaging of the magnetization vector field using Fourier transform holography. Phys. Rev. B 107, 094425 (2023).

Rana, A. et al. Three-dimensional topological magnetic monopoles and their interactions in a ferromagnetic meta-lattice. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 227–232 (2023).

Seki, S. et al. Direct visualization of the three-dimensional shape of skyrmion strings in a noncentrosymmetric magnet. Nat. Mater. 21, 181–187 (2022).

Swift, J. & Hohenberg, P. C. Hydrodynamic fluctuations at the convective instability. Phys. Rev. A 15, 319 (1977).

Elder, K. R., Katakowski, M., Haataja, M. & Grant, M. Modeling elasticity in crystal growth. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 245701 (2002).

Emmerich, H. et al. Phase-field-crystal models for condensed matter dynamics on atomic length and diffusive time scales: an overview. Adv. Phys. 61, 665–743 (2012).

Faghihi, N., Provatas, N., Elder, K. R., Grant, M. & Karttunen, M. Phase-field-crystal model for magnetocrystalline interactions in isotropic ferromagnetic solids. Phys. Rev. E. 88, 032407 (2013).

Seymour, M., Sanches, F., Elder, K. & Provatas, N. Phase-field crystal approach for modeling the role of microstructure in multiferroic composite materials. Phys. Rev. B 92, 184109 (2015).

Backofen, R., Elder, K. R. & Voigt, A. Controlling grain boundaries by magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 126103 (2019).

Reichhardt, C., Reichhardt, C. J. O. & Milošević, M. Statics and dynamics of skyrmions interacting with disorder and nanostructures. Rev. Mod. Phys. 94, 035005 (2022).

Kim, Y. C., Shin, T. J., Hur, S.-M., Kwon, S. J. & Kim, S. Y. Shear-solvo defect annihilation of diblock copolymer thin films over a large area. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw3974 (2019).

Tian, Y. et al. Grain rotation mechanisms in nanocrystalline materials: Multiscale observations in PT thin films. Science 386, 49–54 (2024).

Bechler, N. T. & Masell, J. Helitronics as a potential building block for classical and unconventional computing. Neuromorphic Comput. Eng. 3, 034003 (2023).

Sander, D. et al. The 2017 magnetism roadmap. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 363001 (2017).

Olejník, K. et al. Antiferromagnetic CuMnAs multi-level memory cell with microelectronic compatibility. Nat. Commun. 8, 15434 (2017).

Salvalaglio, M. & Elder, K. R. Coarse-grained modeling of crystals by the amplitude expansion of the phase-field crystal model: an overview. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 30, 053001 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The 3D magnetic laminography was performed at the PolLux (X07DA) endstation of the Swiss Light Source, Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen PSI, Switzerland. The PolLux end station was financed by the German Ministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) through contracts 05K16WED and 05K19WE2. M. Di Pietro Martínez, L. A. Turnbull, J. Neethirajan and C. Donnelly acknowledge funding from the Max Planck Society Lise Meitner Excellence Program and funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the ERC Starting Grant No. 3DNANOQUANT 101116043. M. Di Pietro Martínez and L. A. Turnbull acknowledge the support of the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. M. Salvalaglio acknowledges the support of the Emmy Noether Program of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) project No. 447241406. A. Hierro-Rodríguez and M. Vélez acknowledge support from Spanish MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033/FEDER,UE under grant PID2022-136784NB. The authors acknowledge Markus König and Renate Hempel-Weber for their assistance during FIB and VSM-SQUID experiments, respectively. The authors thank Roderich Moessner and Frank Pollmann for fruitful discussions, their careful reading and insightful comments on this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.D.P.M. and C.D. conceived the project. E.L. and A.M. prepared the samples. M.D.P.M., L.A.T., J.N., M.B., S.F., J.R., and C.D. performed the synchrotron experiments. M.D.P.M. analyzed the data. C.D., A.H.R., and M.V. provided feedback on the data analysis. M.S. and M.D.P.M. developed the model and conducted the simulations. M.D.P.M. and C.D. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Di Pietro Martínez, M., Turnbull, L.A., Neethirajan, J. et al. Unidirectional motion of topological defects mediating continuous rotation processes. npj Spintronics 3, 47 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00111-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00111-1