Abstract

Parametric amplification offers a route to overcoming intrinsic damping in spin-wave systems, a key challenge in the development of magnonic signal processing and computing technologies. Here, we demonstrate the sustained amplification of coherent forward volume magnetostatic spin waves in a yttrium-iron-garnet thin film using a traveling surface acoustic wave as a nonstationary pump. A gain of up to 6 dB is achieved under continuous pumping below the threshold for parametric instability. The interaction generates an idler wave at a distinct frequency, consistent with three-wave mixing governed by energy and momentum conservation. This approach enables stable, frequency- and wavevector-selective spin-wave gain using practical pump power levels, establishing acoustic wave pumping as a viable mechanism for realizing active components in integrated magnonic circuits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Spin waves—coherent, collective excitations of magnetization in ordered magnetic materials—are attracting increasing interest as information carriers for wave-based signal processing and computation devices1,2,3,4. Their quasi-particle analogues, known as magnons, represent the quantized energy and momentum carried by these waves. Practical applications of spin-wave-based or “magnonic” devices have, however, been limited by intrinsic magnetic damping, which causes rapid decay of spin-wave amplitude during propagation. Even in the lowest loss materials, based on yttrium-iron-garnet (YIG), the lifetime of magnons is at most a few microseconds5.

One promising approach to compensating spin-wave damping is parametric pumping, a nonlinear process in which energy from an external oscillating field, typically at twice the spin-wave frequency, is transferred to existing spin-wave modes. Parametric amplification of spin waves has been demonstrated in YIG6,7,8,9 as well as other, higher-loss materials10,11. However, these demonstrations employed spatially uniform magnetic pumping—effectively a stationary, near-field electromagnetic drive—which excites a broad range of modes and often leads to parametric instability once the pump exceeds a critical amplitude. To suppress this instability, previous studies have employed pulsed pumping schemes to limit the duration of energy transfer. In contrast, this work employs a nonstationary, time- and space-periodic pump in the form of a traveling surface acoustic wave (SAW). This configuration provides wavevector-selective gain while remaining below the instability threshold, enabling continuous and stable amplification of coherent spin waves.

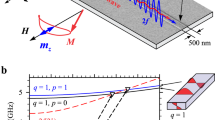

As was recently shown by Geilen et al., the same parametric process also amplifies stochastic spin-waves modes populated by thermal fluctuations12. Using Brillouin light scattering (BLS), they observed the “generation” of spin waves pumped from the thermal background by a SAW. In contrast, we show here the sustained, SAW-pumped parametric amplification of coherent spin waves introduced using inductive transducers. This distinction is critical for signal processing and computational applications, where amplification of deterministic, information-bearing waves is required.

Operating below the threshold for parametric instability13, we demonstrate continuous-wave gain exceeding 6 dB, accompanied by the generation of an idler wave, consistent with three-wave mixing. This approach achieves stable, frequency- and wavevector-selective amplification at practical power levels, offering a scalable mechanism for realizing active functionality in magnonic devices.

Results

Acoustic parametric amplification of spin waves

The acoustic wave and spin wave interact via magnetoelastic coupling in YIG, by which the strain in the acoustic wave modulates the magnetic anisotropy. This time- and space-periodic modulation of the anisotropy can, under the conditions outlined below, result in the parametric amplification of an existing spin wave. In the process, energy and momentum are transferred from the acoustic wave to the spin wave. In the quasi-particle interpretation, the process is described as a stimulated down-conversion of a phonon from the acoustic pump into two lower-energy magnons, one with frequency and wave vector matching the existing “signal” spin wave and the other contributing to a secondary wave, conventionally called the “idler” wave. The idler wave must exist to satisfy the conservation of energy, \(\hslash \omega\), and momentum, \(\hslash {\boldsymbol{k}}\), in the three-wave mixing process. Specifically, the energy of the pump phonon lost must equal the sum of the energies of the two resulting magnons, giving the relation,

in which ωp, ωs, and ωi are the radian frequencies of the pump, signal, and idler waves, respectively. Likewise, the momenta of the created magnons must add up to the momentum of the pump phonon lost, giving,

where kp, ks and ki are the respective wave vectors.

Experimentally, we consider here only the degenerate case, where ωs = ωi (i.e., the energies of the two magnons are the same) and the acoustic pump frequency is therefore twice the spin wave frequency. With a perpendicular magnetic bias field, the YIG film supports forward volume magnetostatic spin-wave modes with nearly isotropic in-plane propagation characteristics. Thus, for ωs = ωi we also have |ks| = |ki| and, to satisfy the vector sum in (2), the idler will travel away from the interaction region with angle13

where θs is the angle of incidence of the signal wave with respect to the pump and θi is the angle at which the idler leaves the pumping region (see Fig. 1a). Accordingly, for degenerate pumping at a given angle of incidence, the magnitudes of the wave vectors must be related by

The parametric interaction can thus occur if the spin-wave dispersion curve is adjusted, by means of the bias field, to pass through the point \({\omega }_{p}/2\), \(|{{\boldsymbol{k}}}_{{\boldsymbol{p}}}|/2\cos {(\theta }_{s})\), as illustrated in Fig. 1b.

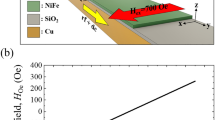

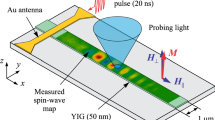

a Illustration of the parametric interaction between a spin wave and a SAW pump. b Calculated dispersion curves for forward volume spin waves in a 1 µm-thick YIG film and surface acoustic waves in a layered medium of ZnO (425 nm) on YIG. In the parametric pumping interaction, a pump phonon splits into two magnons of half the pump frequency, and the wave vectors must satisfy the conservation relation in Eq. (2). c Experimental configuration. Spin waves are excited and detected in the YIG film by inductive transducers. The surface acoustic wave pump is generated using an interdigitated transducer (IDT) on piezoelectric ZnO. The bias magnetic field is oriented perpendicular to the film plane. d Optical micrograph of a fabricated device showing the layout of the transducers. (The L-shaped features near the spin wave transducers are inadvertent artifacts of the lithography process and do not impact the experiments).

As we have previously shown theoretically14 and by micromagnetic modeling15, the strength of the parametric interaction of forward volume waves pumped by SAWs depends on the angle of incidence, a consequence of the elliptical polarization of the spin waves and the phase difference between the longitudinal and perpendicular strain components of the SAW. The parametric coupling strength in the YIG film has a minimum around 20° and increases with increasing angle of incidence. Therefore, we use as large an angle as practical in the experiments, limited by the transducer linewidths that can be reliably patterned.

The device shown in Fig. 1d was fabricated to experimentally investigate the SAW pumping of spin waves. SAWs with a wavelength of 1.5 µm and a frequency of approximately 2 GHz are generated using an Al interdigitated transducer (IDT) on a thin film of piezoelectric ZnO. The acoustic waves penetrate the ZnO as well as the underlying 1-µm-thick YIG film (see Fig. S5). Inductive spin wave transducers were arranged to launch a beam of spin waves to intersect the SAW at an angle, θs = 30°. The spin-wave transducers were designed for wavelengths of 2.6 µm in accordance with (4). The parametrically pumped signal spin wave is detected on the opposite side with an identical transducer. A third transducer was arranged to detect the idler spin wave at the symmetrical angle, θi = −30°.

Experimental results

To investigate the acoustic parametric amplification of spin waves, the signal transmitted between the opposing transducers was measured using a vector network analyzer, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The transmission spectra, S21, without pumping and at two different pump power levels are plotted in Fig. 2b. The central peak, arising from the transmitted signal spin wave, grows with increasing pump power. (The transmission spectrum is displaced slightly to the right with increasing pump power as the acoustic wave shifts the spin-wave dispersion curve by reducing the average magnetization in the film.) The peak received signal power is plotted in Fig. 2c as a function of SAW pump power for different levels of signal input power. To better visualize the amplification, the same data are replotted in Fig. 2d to show the gain in signal power relative to the unpumped baseline. Clear gain is observed for pump powers exceeding 0 dBm, rising monotonically to a maximum gain of approximately 6 dB near 10 dBm pump power. Beyond this point, the gain begins to decline, likely due to higher-order nonlinear processes or the onset of parametric instabilities generating unwanted spin-wave modes that scatter energy away from the desired signal. The gain is independent of input signal power until the spin waves are driven into the nonlinear regime around -20 dBm.

a Experimental setup for measuring signal transmission and gain. b Transmission spectra from input to output transducer for various pump powers. c Peak signal output power measured as a function of SAW power for different levels of input signal power. d Gain in transmitted signal power normalized to the unpumped transmission. e Experimental setup for measuring idler power. f Spectra observed at the idler output showing the generated idler signals at fi, along with feedthrough of the signal frequency at fs and spin waves pumped from the thermal background at \({f}_{p}/2\). g Detected idler power as a function of SAW pump power for different levels of input signal power. h Signal detected at exactly \({f}_{p}/2\), resulting from the pumping of spin waves from the thermal background.

The idler wave is detected at the third transducer using a spectrum analyzer as illustrated in Fig. 2e16. For this measurement, the signal frequency was detuned from the degenerate condition by 1 kHz (0.0001%) so that the idler frequency is slightly different and can be distinguished from feedthrough of the input signal as seen in Fig. 2f. The signal observed at \({f}_{s}=\frac{{f}_{p}}{2}-1\text{kHz}\) is due to electromagnetic feedthrough between the spin-wave transducers. The idler observed at \({f}_{i}=\frac{{f}_{p}}{2}+1\text{kHz}\) is a new frequency generated in the parametric interaction consistent with (1). The detected idler power as a function of SAW power is plotted in Fig. 2g for varying levels of signal input power. The appearance of the idler at very low pump power confirms that the threshold-less parametric interaction with the coherent signal wave is occurring even though the power added to it does not result in an appreciable amplification.

The idler appears only when the bias magnetic field is tuned to position the spin wave dispersion curve as shown in Fig. 1b, allowing for the three-wave interaction (see Fig. S2). In the absence of either signal input or pump, no idler is detected above the background noise level of −165 dBm. The idler peak increases bilinearly with both input signal power and pump power (Fig. 2g), as expected17 for the three-wave mixing process stimulated by the signal wave. Above 10 dBm pump power, the idler also shows deviation, again suggesting the onset of higher-order effects or instability.

In addition to the signal and idler, a third spectral component appears in Fig. 2f at exactly \(\frac{{f}_{p}}{2}\), the degenerate condition. As seen in Fig. 2h, the power detected at this frequency is independent of the input signal power but grows with pump power. This new component is attributed to the parametric amplification of thermally populated magnon modes to levels detectable above the noise floor of the spectrum analyzer. This process occurs initially at the degenerate condition and broadens at higher pump power to include nearby frequencies (Fig. 2f). The broadband excitation of spin waves at the higher pump powers may also be responsible for the increase in signal output power observed in Fig. 2c above 13 dBm SAW power.

Similar results, consistent with (1) and (4), were obtained with separate experimental devices having spin-wave transducers arranged at angles varying from 0° to 45° with respect to the SAW propagation (see Fig. S1).

Discussion

The experimental results summarized in Fig. 2 demonstrate sustained parametric amplification of coherent forward volume spin waves in a YIG film. The traveling SAW pump provides both temporal and spatial modulation, enabling frequency- and wavevector-selective coupling to spin-wave modes. This spatiotemporal selectivity allows continuous-wave operation without triggering parametric instability, a key limitation of conventional spatially-uniform magnetic field pumping. The detection of an idler wave at the expected frequency and angle, with bilinear power dependence, confirms the underlying three-wave mixing mechanism.

To evaluate whether the amplification truly overcomes intrinsic magnetic damping, we estimate the spin-wave decay length based on typical values of damping in these types of films. Using a Gilbert damping parameter of α = 0.000618, the decay length for 2.6 µm spin waves is about 780 µm19. Over the 140 µm propagation distance between the transducers, this corresponds to an intrinsic loss of about 1.6 dB. The observed amplification of up to 6 dB exceeds the loss, providing a net gain of more than 4 dB. The SAW strain amplitude required to achieve this gain is estimated to be ~60 ppm (see Fig. S5), which is well within the operating range of standard SAW devices20. Larger signal gains could, in principle, be achieved by increasing the path length over which the spin wave is pumped by the SAW.

Beyond providing gain, parametric pumping with a traveling wave, when operating under nondegenerate conditions, enables spectral and spatial manipulation of spin-wave signals through the generation of an idler at frequencies and angles distinct from the input spin wave. This capability can support analog signal processing operations such as frequency translation21, channel separation, directional control, and nonreciprocal signal transmission.

In conclusion, this demonstration of directional, frequency-selective amplification under continuous pumping conditions establishes a new approach to spin-wave manipulation. The mechanism offers several advantages for the development of functional magnonic elements: it compensates intrinsic losses, preserves coherence, and permits frequency- and direction-resolved signal routing. As highlighted in prior studies2,3,4, such capabilities are essential for realizing spin-wave repeaters, logic gates, and active interconnects in wave-based signal processing and computing systems. The low power requirements and compatibility with established acoustic device structures further support integration into chip-scale circuits. Acoustic pumping thus offers a scalable and versatile tool for enabling coherent, active functionality in emerging magnonic technologies.

Methods

Transducer design

The SAW transducers are conventional IDTs using piezoelectric ZnO to mediate the electromechanical coupling22. The shortest achievable wavelength, and correspondingly highest frequency, of the SAW pump was limited by the linewidths that could be reliably patterned. The finger pitch of the IDTs was 0.75 µm (0.325 µm line and space) to obtain a SAW wavelength of 1.5 µm. With a calculated SAW phase velocity on the layered ZnO/YIG/GGG surface of around 3000 m/s this wavelength corresponds to a designed operating frequency near 2 GHz. The synchronous frequency of the fabricated transducer was measured to be 2048.2 GHz (see Fig. S5). The IDTs have 50 finger pairs of 70 µm overlapping length to produce a 70 µm wide SAW beam.

The spin wave transducers are meandering coplanar ground-signal-ground waveguides with 6 meanders of 34 µm length to produce a 34 µm wide spin wave beam. The wavelength of the spin waves excited (or detected) equals twice the conductor-to-conductor spacing, designed to satisfy λs = 2 × 1.\(5\) µm cos(30°) = 2.6 µm according to (4). The spacing loss due to the intervening ZnO results in relatively poor spin wave transduction efficiency with an estimated additional insertion loss per transducer of 30 dB. This loss was accepted over the additional fabrication complexity of removing the ZnO under the spin wave transducers.

Due to the differing spatial periodicity of the two types of transducers, inadvertent excitation of propagating spin waves by the IDT or excitation of a propagating SAW by the spin wave transducer is not possible at the designed drive frequencies.

Device fabrication

The devices were fabricated on commercially available wafers (Innovent, e.V., Jena, Germany) consisting of a 1‑μm‑thick yttrium-iron-garnet (YIG) film grown by liquid-phase epitaxy on a <111> -oriented gadolinium gallium garnet (GGG) substrate. A 425 nm layer of zinc oxide (ZnO) was deposited on the YIG by magnetron sputtering. The ZnO thickness chosen is a trade-off between achieving good crystalline texture for piezoelectric coupling and ensuring sufficient penetration of SAW strain into the YIG film.

Interdigitated and meander-line transducers were patterned by reactive ion etching of a 160-nm-thick aluminum layer evaporated onto the ZnO, with a 5 nm titanium adhesion layer. Electron-beam lithography was used to define the fine transducer features, while optical lithography was employed for the larger probe pads. Scanning electron microscope images of the fabricated transducers are shown in Fig. 3.

Bias field adjustment

The perpendicular magnetic bias field required to support forward volume spin waves was applied using a cylindrical (50 mm diameter, 25 mm thick) NdFeB permanent magnet surrounded with an electromagnet coil for tuning. For a given spin-wave excitation frequency, the magnetic field is adjusted to obtain a maximum in the transmission between the input and output transducers. At this field, the wavelength of the spin waves matches the periodicity of the meander-line transducer.

Due to the thin-film shape anisotropy, even a small angular deviation of the external bias field from the perpendicular orientation can lead to a much larger deviation of the internal field and magnetization angle. Consequently, the results are very sensitive to the alignment of the bias field, which is adjusted by tilting the magnet assembly in the experimental setup. The perpendicular orientation is found by tuning the tilt until a minimum is obtained in the frequency spectrum of transmitted spin waves23.

Measurements

A vector network analyzer (Agilent E5071C) was used to measure the transmission and amplification of signal spin waves from the input transducer to the output transducer. The “time gating” feature24 of the network analyzer was used to eliminate electromagnetic feedthrough of the signal between the cabling and transducers. Since the spin wave signal can be distinguished from the electromagnetic coupling by its longer transit time, a time gate of 50 ns can be used to eliminate the feedthrough.

The SAW is excited by driving the IDT at its synchronous frequency, fp = 2048.2 MHz, with a continuous sinusoidal signal from a microwave signal generator (Stanford Research Systems SG384).

For the idler measurements, the input spin wave transducer is driven with a continuous sinusoidal signal from a microwave signal generator (Agilent N5183A) while the idler output signal is observed using a spectrum analyzer (Tektronix RSA3308B). In this case, the idler signal is distinguished from the feedthrough by shifting the signal frequency down by 1 kHz relative to the degenerate case, i.e., fs = 1024.099 MHz instead of 1024.1 MHz. The resulting idler is, according to (1), shifted up by 1 kHz to 1024.101 MHz, where it can be separated from the feedthrough using a 7.8 Hz resolution bandwidth on the spectrum analyzer.

All electrical connections to the device were through 50 Ω coaxial cables and coplanar ground-signal-ground microwave probes. For both the network analyzer as well as the spectrum analyzer measurements, a low-noise amplifier (Mini Circuits ZKL-33ULN-S+, not shown in Fig. 2) is used to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Dispersion calculations

The dispersion curve for forward volume waves in the YIG film, shown in Fig. 1b, was calculated using the approximate formula derived by Kalinikos and Slavin25,

for a film with thickness, d = 1 µm, using \({\omega }_{M}=-\gamma {\mu }_{0}{M}_{S}\) and \({\omega }_{0}=-\gamma {\mu }_{0}{H}_{0}\) with H0 being the perpendicular magnetic bias field. We used standard values for the gyromagnetic ratio, γ = −2π × 28 GHz/T, vacuum magnetic permeability, μ0 = 1.257×10-6 H/m, and saturation magnetization, MS = 140 × 103 A/m for YIG18.

The dispersion curve for the SAW traveling on the layered ZnO/YIG/GGG surface was calculated numerically using Green’s function analysis26 with the following material properties27: density, ρ = 5.6 g/cm3, elastic constants, C11 = 209.7 GPa, C12 = 121.1 GPa, C13 = 105.1 GPa, C33 = 210.9 GPa, C44 = 42.5 GPa for ZnO; ρ = 5.17 g/cm3, C11 = 269 GPa, C22 = 108 GPa, C44 = 76.4 GPa for YIG; and ρ = 7.094 g/cm3, C11 = 285.7 GPa, C22 = 114.9 GPa, C44 = 90.2 GPa for GGG.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study, including simulation results and experimental measurements, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Pirro, P., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Advances in coherent magnonics. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1114–1135 (2021).

Levchenko, K. O., Davídková, K., Mikkelsen, J. & Chumak, A. V. Review on spin-wave RF applications. arXiv Prepr. arXiv2411.19212 (2024).

Chumak, A. V. et al. Advances in magnetics roadmap on spin-wave computing. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58, 1–72 (2022).

Flebus, B. et al. The 2024 magnonics roadmap. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 36, 363501 (2024).

Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453–461 (2015).

Kolodin, P. A. et al. Amplification of microwave magnetic envelope solitons in thin yttrium iron garnet films by parallel pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 1976–1979 (1998).

Bagada, A. V., Melkov, G. A., Serga, A. A. & Slavin, A. N. Parametric interaction of dipolar spin wave solitons with localized electromagnetic pumping. Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 2137 (1997).

Melkov, G. A., Kobljanskyj, Y. V., Serga, A. A., Tiberkevich, V. S. & Slavin, A. N. Nonlinear amplification and compression of envelope solitons by localized nonstationary parametric pumping. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 6689–6691 (2001).

Serga, A. A., Demokritov, S. O., Hillebrands, B., Min, S.-G. & Slavin, A. N. Phase control of nonadiabatic parametric amplification of spin wave packets. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 8585–8587 (2003).

Brächer, T. et al. Parallel parametric amplification of coherently excited propagating spin waves in a microscopic Ni81Fe19 waveguide. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 202408 (2014).

Hanna, S. M., Murphy, G. P. & Science, C. Interactions between magnetostatic and surface Acoustic waves in garnet films. IEEE Trans. Magn. 24, 2814–2816 (1988).

Geilen, M. et al. Parametric excitation and instabilities of spin waves driven by surface acoustic waves. Adv. Phys. Res. 4, 2400086 (2025).

Rivard, C., Jander, A. & Dhagat, P. Parametric instability of forward volume spin waves pumped by surface acoustic waves in yttrium iron garnet films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 127, 042408 (2025).

Lisenkov, I., Jander, A. & Dhagat, P. Magnetoelastic parametric instabilities of localized spin waves induced by traveling elastic waves. Phys. Rev. B 99, 184433 (2019).

Rivard, C., Jander, A. & Dhagat, P. Micromagnetic modeling of parametric amplification of forward volume spin waves by noncollinear surface acoustic waves. IEEE Magn. Lett. 15, 5500205 (2024).

Jander, A., Dhagat, P. & Rivard, C. Parametric pumping of coherent spin waves by surface acoustic waves. J. Appl. Phys. 137, 073902 (2025).

L’vov, V. S. Wave Turbulence Under Parametric Excitation: Applications to Magnets. (Springer, 2012).

Dubs, C. et al. Sub-micrometer yttrium iron garnet LPE films with low ferromagnetic resonance losses. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 204005 (2017).

Stancil, D. D. & Prabhakar, A. Spin Waves: Theory and Applications. (Springer, 2009).

Abracon L. L. C. SAW Filters – Performance Characteristics, Part I. (2021). Available at: https://abracon.com/uploads/resources/Abracon-SAW-Filters-Part-I.pdf

Mohseni, M., Hamadeh, A. A., Geilen, M. & Pirro, P. Amplification and frequency conversion of spin waves using acoustic waves. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 22, 806–810 (2023).

Ryburn, F. et al. Generation of gigahertz-frequency surface acoustic waves in Y3Fe5O12 /ZnO heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 34062 (2025).

Lemons, R. A. & Auld, B. A. The effects of field strength and orientation on magnetostatic wave propagation in an anisotropic ferrimagnetic plate. J. Appl. Phys. 52, 7360–7371 (1981).

Keysight Technologies. Application note: Time Domain Analysis Using a Network Analyzer. Available at https://www.keysight.com/us/en/assets/7018-01451/application-notes/5989-5723.pdf (2024).

Kalinikos, B. A. & Slavin, A. N. Theory of dipole-exchange spin wave spectrum for ferromagnetic films with mixed exchange boundary conditions. J. Phys. C. Solid State Phys. 19, 7013 (1986).

Li, D. Surface acoustic wave techniques in laser pump-probe systems and its applications in studying mechanical properties of materials. (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017).

Slobodnik, A. J., Delmonico, R. T. & Conway, E. D. Microwave Acoustics Handbook. (Air Force Cambridge Research Laboratories, 1974).

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.R. designed and fabricated the devices, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and prepared the figures. A.J. and P. D. conceived the experiments and co-directed the project. A.J. prepared the initial draft of the manuscript. P.D. helped revise it. All authors contributed to the experimental design and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors C.R. and A.J. declare no financial or non-financial competing interests. P.D. serves as an Editor of this journal and had no role in the peer-review or decision to publish this manuscript. P.D. declares no financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rivard, C., Jander, A. & Dhagat, P. Sustained amplification of coherent spin waves by parametric pumping with surface acoustic waves. npj Spintronics 3, 49 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00115-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00115-x