Abstract

The Co2FeSi/Fe/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 interface exhibits the strong magnetoelectric coupling arising from the magnetocrystalline anisotropy (MCA) of Co2FeSi. To enable the design of the MCA based on crystal structures and plane orientations, we examined the relationship between the atomic configurations and the MCA of Co2FeSi under strain within the (001) and (422) planes. Despite exhibiting similar MCA under strain within the (001) and (422) planes, the MCA origin differs. Under strain within the (422) plane, the MCA arises from the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the 3d orbitals extended in the plane perpendicular to the magnetization direction. In contrast, under strain within the (001) plane, Fe atoms are coordinated by Si atoms within the (100) and (010) planes, which suppresses the orbital magnetic moments of Fe and their contributions to the MCA. Furthermore, under strain within the (422) plane, Co and Fe atoms contribute oppositely to the MCA due to differences in the behavior of the orbital magnetic moments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Electric-field control of magnetization based on the magnetoelectric (ME) coupling observed in multiferroics1 is expected to become a key component for realization of energy-efficient magnetoresistive random access memory (MRAM). As a promising non-volatile magnetic memory device, MRAM has been extensively investigated for power reduction and miniaturization2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. The energy required to generate an electric field is lower than that needed for a magnetic field2,3,4, because electric-field control reduces energy loss due to Joule heating in conventional current-driven methods, enabling power saving5,6,7. Magnetization can be controlled by methods such as adjusting the perpendicular magnetic anisotropy at the tunnel junction interface8,9 or generating pure spin currents in magnetic tunnel junctions (MTJs)10.

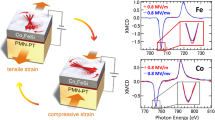

A strong converse ME coupling is observed in Co2FeSi/Fe/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 (PMN-PT) heterostructures attributed to the strain-induced magnetocrystalline anisotropy (MCA) of the Co2FeSi23,24. The ME coupling and its origin have been investigated in various system beyond this system24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. In Co2FeSi/Fe/PMN-PT heterostructures, an electric field applied to the PMN-PT substrate induces strain via the inverse piezoelectric effect. The strain is transferred to the Co2FeSi layer across the interface, thereby enabling control of the MCA through magnetoelastic coupling23,24,70,71. The strength of this coupling of Co2FeSi depends on the plane orientation, exhibiting a high ME coupling coefficient α = 1.8 × 10−5 s m−1 when oriented along the (422) plane on the substrate24. This value exceeds the practical requirement of α > 10−5 s m−172,73,74. Additionally, Co2FeSi is a ferromagnetic Heusler alloy with high spin polarization and the Curie temperature, making it a promising candidate for spintronics applications75,76,77,78,79,80,81. Heusler alloys have been studied for their magnetic properties due to their potential for spintronics82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89. Spin polarization and the Curie temperature in Heusler alloys depend on structural order. For example, Co2CrAl shows a rapid decrease in spin polarization due to Co-Cr disorder86. In contrast, Co2FeSi maintains high spin polarization at room temperature and has the high Curie temperature of about 1100 K75,76.

The MCA arises from spin-orbit coupling (SOC). By affecting electronic structure and magnetism25,26,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111, SOC plays a key role in spintronics. In several transition metal-based systems, second-order perturbation with respect to the SOC Hamiltonian112 is valid25,26,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104, since the first-order perturbation term vanishes113. Based on perturbative approximations, the MCA of Co2FeSi has often been described by the Bruno and van der Laan terms from each atom. The Bruno term arises from spin-conserving virtual excitations from occupied down-spin to unoccupied down-spin states and is related to the orbital magnetic moments90. Alternatively, the van der Laan term arises from the spin-flip virtual excitations from occupied up-spin to unoccupied down-spin states and is related to the quadrupole moments of the spin density91,92,93. The contributions of these terms were examined for the energy difference for magnetization along the 〈100〉 directions under a highly symmetric (001) in-plane strain. Here, the MCA arises mainly from the van der Laan term from Co, i.e., the quadrupole moments of the spin density at the Co site enhance the MCA. The Bruno term from Co and the contributions from Fe have little effect on or suppress the MCA25,26. In the system exhibiting a high ME coefficient α = 1.8 × 10−5 s m−1, Co2FeSi is epitaxially grown on the PMN-PT(011) substrate following the relation of Co2FeSi(422)∥PMN-PT(011)24. Therefore, the contributions were also examined for the energy difference between magnetization along the \([01\bar{1}]\) and \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\) directions within the (422) plane under in-plane strain. In this case, the orbital magnetic moments at the Fe site are modulated and enhance the MCA70. The Bruno and van der Laan terms have not been explicitly evaluated for the (422) plane.

Despite the dependence of the MCA and the ME coupling on the plane orientation, the relationship between the atomic configurations and the MCA remains unclear. In this study, we investigate the MCA and its origin in Co2FeSi under strain within the (001) and (422) planes based on first-principles calculations. The purpose is to reveal the effects of the atomic configurations on the MCA by comparing these results. This understanding is expected to enable the design of the MCA based on crystal structures and plane orientations. In particular, Co2MnSi and Co3Mn exhibit the MCA and the ME coupling similar to Co2FeSi25,68,114,115, indicating their potential for applications.

Results

Unit cell and total density of states

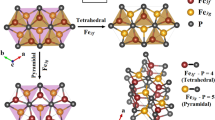

Co2FeSi crystallizes in the L21-ordered structure with space group \(Fm\bar{3}m\), as shown in Fig. 1(a) and (b). The Fe, Si, and Co atoms occupy the 4a, 4b, and 8c Wyckoff sites, respectively. The system is ferromagnetic, as all other antiferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic configuration within the 1 × 1 × 1 unit cell were unstable, which is consistent with results reported in ref. 81. The systems with in-plane strain applied within the (001) and (422) planes are denoted as CFS(001) and CFS(422), respectively. For CFS(001), the [100], [010], and [001] directions are set as the a-, b-, and c-axes, while for CFS(422), the \([0\bar{1}1]\), \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\), and [211] directions are set, respectively. For both systems, strains εa and εb ranging from −2% to + 2% were independently applied along the a- and b-axes, respectively. Here, εa = (a − a0)/a0 and εb = (b − b0)/b0, where a0 and b0 are the unstrained lattice constants. Figure 1(c) shows the total density of states (DOS) of unstrained Co2FeSi, which exhibits half-metallicity.

a a-, b-, and c-axes are set to [100], [010] and [001], respectively. b a-, b-, and c- axes are set to \([0\bar{1}1],[1\bar{1}\bar{1}],{\rm{and}}[211]\), respectively. These cells (a) and (b) were generated using VESTA124. c Total density of states (DOS) per atom of unstrained Co2FeSi.

Magnetocrystalline anisotropy energy

Figure 2 shows the diagram of the magnetization easy axes and the MCA energy of the Co2FeSi alloy as a function of the in-plane strains, εa and εb. The magnetization easy axis in unstrained Co2FeSi is 〈110〉 direction. Except for εa ≈ εb in CFS(001), either the a- or b-axis is the magnetization easy axis under strain. Therefore, the MCA energy EMCA is defined as the difference between \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}\), i.e., \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}={E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}-{E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\). Here, \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}\) denote the energy arising from the SOC with magnetization aligned along a- and b-axes, respectively. For CFS(422), the a- and b-axes are inequivalent; therefore, EMCA ≠ 0 holds even for the unstrained CFS(422). We evaluated the partial derivative of the MCA energy with respect to strain, based on an ordinary least squares (OLS) method. For CFS(001), ∂EMCA/∂ε[100] = − ∂EMCA/∂ε[010] = 0.7732 meV atom−1. In the case of CFS(422), \(\partial {E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}/\partial {\varepsilon }^{[0\bar{1}1]}=0.8634\,{\rm{meV}}\,{{\rm{atom}}}^{-1}\) and \(\partial {E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}/\partial {\varepsilon }^{[1\bar{1}\bar{1}]}=-0.8644\,{\rm{meV}}\,{{\rm{atom}}}^{-1}\). These results show that the tensile strain in the a-axis decreases EMCA and the tensile strain in the b-axis increases EMCA, in both CFS(001) and CFS(422). By the definition \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}={E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}-{E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\), the decrease in MCA energy makes the state with magnetization along the a-axis lower in energy than that along the b-axis. Conversely, the increase in MCA energy makes the state with magnetization along the b-axis lower in energy than that along the a-axis. Those indicate that tensile strain makes the strained axis the magnetization easy axis. Considering compressive strain as well, compressive strain makes the strained axis the magnetization hard axis. Furthermore, the strain within the (422) plane induces a larger change in the MCA energy than the strain applied within the (001) plane. This trend is consistent with previous studies under different strains or interface configurations24,25,26.

Contributions to the MCA can be decomposed into four terms, based on the spin orientations of unperturbed occupied and virtual states in the second-order perturbation theory94,98,100,103:

Here, \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}{\sigma }_{2}}\) denotes the MCA energy due to the virtual excitation from the occupied spin σ1 state to the unoccupied spin σ2 state. When the up-spin states are essentially fully occupied, the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \uparrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \uparrow }\) can be considered negligible. Applying additional approximations, \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) are related to the van der Laan and Bruno terms, respectively90,91,92,93. In a previous study of CFS(001)25,26, the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \uparrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \uparrow }\) have small values because there are few unoccupied up-spin bands. The \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) from Co 3d states mainly enhance the MCA, whereas the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) terms have little effect on or suppress the MCA. In contrast, The \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) from Fe 3d states have little effect on the MCA25,26.

For CFS(422), we analyze the site-decomposed EMCA given by Eq. (1), as shown in Fig. 3. Similar to CFS(001)25,26, the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \uparrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \uparrow }\) contribute little to the MCA because there are few unoccupied up-spin bands as shown in Fig. 1(c). For Co, the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) change significantly under strains. However, their opposite dependence on the strain causes partial cancellation, resulting in a small net contribution. In contrast, for Fe, the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) change significantly and same dependence on the strain. Unlike CFS (001), Fe plays a significant role in the enhancement of the MCA.

The partial derivatives of the site-decomposed MCA energy per atom \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \uparrow },{E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \uparrow },{E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow },{\rm{and}}\,{E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) with respect to (a) a-axis strain \({\varepsilon }^{[0\bar{1}1]}\) and (b) b-axis strain \({\varepsilon }^{[1\bar{1}\bar{1}]}\).

Orbital magnetic moment

We focus on the spin-conserving term \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }={E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }(b)-{E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }(a)\). The \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }(\zeta )\) is related to the Bruno terms90,94,103:

Here, ζ is the magnetization direction, μB is the Bohr magneton, and ξ is the SOC constant. Equation (2) indicates that \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\propto {m}_{{\rm{orb}}}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\propto \Delta {m}_{{\rm{orb}}}={m}_{{\rm{orb}}}(b)-{m}_{{\rm{orb}}}(a)\), where Δmorb denotes the anisotropy of the orbital magnetic moment. Furthermore, ESOC(EMCA) decreases with increasing morb(Δmorb).

Because \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}\downarrow }\) arises from the virtual excitation from the occupied spin σ1 state to the unoccupied down-spin state, the modulation of unoccupied down-spin density of states (DOS) contributes to \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}\downarrow }\). This modulation also contributes to morb since morb arises from the virtual excitation from the occupied down-spin state to the unoccupied down-spin state, as indicated in Eq. (2). In a previous study of CFS(422)70, for Fe, the local DOS of the unoccupied down-spin 3d states is modulated by strain, which primarily corresponds to the modulation of Δmorb70. This strain-induced modulation of DOS also corresponds to \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) and \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) as shown in Fig. 3. For Co, the strain-induced modulation of \(\Delta {m}_{{\rm{orb}}}={m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}-{m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}\) is small because \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}\) and \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}\) vary similarly with strain70.

To examine these contributions, we analyzed the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the d orbitals of Co and Fe in Co2FeSi. The orbital angular momentum eigenstate \(\left\vert \zeta ,l,m\right\rangle\) is defined with ζ, l, and m denoting the quantization axis, azimuthal quantum number, and magnetic quantum number, respectively. It can be expressed as a linear combination of the d-orbital basis states \(| \mu \rangle =| {{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\rangle ,| {{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\rangle ,| {{\rm{d}}}_{yz}\rangle ,| {{\rm{d}}}_{zx}\rangle ,| {{\rm{d}}}_{xy}\rangle\) defined with the quantization axis along the z-axis:

The d orbitals corresponding to the \(\left\vert \zeta ,2,\pm 2\right\rangle\) states have the maximum magnitude of the azimuthal orbital angular momentum, i.e., ∣m∣ = 2, extending in the ζ-plane perpendicular to the magnetization direction ζ. Based on the relationship the d orbitals and the states given by Eqs. (3–8), the d orbitals corresponding to the \(\left\vert x,2,\pm 2\right\rangle\) states are \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\), \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), and dyz, whereas the d orbitals corresponding to the \(\left\vert y,2,\pm 2\right\rangle\) states are \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\), \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), and dzx. Therefore, significant contributions to the MCA are expected from the \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\), \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), and dyz(dzx) orbitals when magnetization is aligned along the a(b)-axis.

Figure 4 shows the partial derivatives of the anisotropy in the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the d orbitals with respect to strains. For Co, the anisotropy of the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the d orbitals with m = ± 2 generally increases (decreases) under tensile strain along the a(b)-axis in both CFS(001) and CFS(422). This likely suppresses the MCA shown in Fig. 3. In contrast, for Fe, the change in the anisotropy appears to be opposite to that of Co, indicating its enhancement of the MCA. As for CFS(001), this change is relatively minor and makes only a small contribution to the MCA.

The partial derivatives of anisotropy in the orbital magnetic moment projected onto the d orbitals of Co and Fe with respect to the (a) a-axis strain εa and (b) b-axis strain εb. The anisotropy in the orbital magnetic moment Δmorb(μa, μb) is defined as a difference between \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}({\mu }^{a})\) and \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}({\mu }^{b})\). Here, \({\mu }_{{\rm{orb}}}^{\zeta }({\mu }^{\zeta })\) is the orbital magnetic moments projected onto orbital μ with magnetization aligned along ζ-axis.

D03-ordered Co3Mn exhibits a similar atomic configuration and the MCA as Co2FeSi. By identifying Co atoms at the 8c sites (CoI) and 4b sites (CoII), the structure can be considered as the L21 structure. Similar to Co2FeSi, the axis under tensile strain becomes the magnetization easy axis68. However, when strain is applied within the (001) plane, both the CoI and the Mn atoms enhance the MCA, while the CoII atoms suppress it68. In contrast, in Co2FeSi, only the Co atoms at the 8c site enhance the MCA under the same conditions.

Figure 5 (a) shows the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the d orbitals of Co and Fe in unstrained Co2FeSi. Figure 5(b) and (c) show the partial derivatives of the orbital magnetic moments with respect to strains. Except for Fe in CFS(001), the orbital magnetic moments projected onto the d orbitals with m = ± 2 of unstrained Co2FeSi are large. As a result, the orbital magnetic moments change is also enhanced, indicating a large change in this anisotropy. In contrast, for Fe in CFS (001), the orbital magnetic moments with m = ± 1 is relatively large, whereas that with m = ± 2 is small. This can be attributed to Fe atoms coordinated by covalently bonded Si atoms in the (100) or (010) planes. This difference between CFS(001) and CFS(422) affects the partial DOS of Fe \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\) states in unstraind Co2FeSi as shown in Fig. 5(d). The partial DOS of occupied down-spin \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\) bands in CFS(422) are larger than those in CFS(001), which increases the contributions from the couplings \(\langle {{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}^{\downarrow }| {\hat{L}}_{x}| {{\rm{d}}}_{yz}^{\downarrow }\rangle\), \(\langle {{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}^{\downarrow }| {\hat{L}}_{x}| {{\rm{d}}}_{yz}^{\downarrow }\rangle\), \(\langle {{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}^{\downarrow }| {\hat{L}}_{y}| {{\rm{d}}}_{zx}^{\downarrow }\rangle\), and \(\langle {{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}^{\downarrow }| {\hat{L}}_{y}| {{\rm{d}}}_{zx}^{\downarrow }\rangle\) in CFS(422). As a result of these contributions, the orbital magnetic moments \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}\) of \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\), dyz in CFS(422) are larger than that of CFS(001), whereas the orbital magnetic moments \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}\) of \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\), \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\), dzx in CFS(422) are larger than that of CFS(001).

a The orbital magnetic moments in unstrained Co2FeSi. The partial derivatives of the orbital magnetic moments with respect to (b) a-axis strain εa and (c) b-axis strain εb. Each orbital magnetic moment is projected onto the d orbitals of Co and Fe. d The partial DOS of Fe \({{\rm{d}}}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) and \({{\rm{d}}}_{{z}^{2}}\) states in unstraind CFS(001) and CFS(422).

Furthermore, for Co, strain causes a larger change in the orbital magnetic moments with the magnetization perpendicular to the strain than the parallel case. In contrast, for Fe, the orbital magnetic moments change more when magnetization is parallel to the strain. This difference affects both anisotropy of the orbital magnetic moments and its role in contributing to the MCA.

Figure 6 shows partial derivatives of site-decomposed spin-conserving term \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) with respect to strain applied within the (422) plane. As indicated by Eq. (2), the changes in the \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) correspond to the changes in the orbital magnetic moment. Specifically, for Co, the energy changes more when magnetization aligns perpendicular to the strain, whereas for Fe, it changes more when magnetization aligns parallel. These trends correspond to the changes observed in the orbital magnetic moment.

Discussion

Co2FeSi exhibits the MCA such that tensile strain makes the strained axis the magnetization easy axis, whereas compressive strain makes the strained axis the magnetization hard axis. However, while only the spin-flip terms \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\uparrow \downarrow }\) from Co enhance the MCA under strain within the (001) plane, Fe atoms also enhance under strain within the (422) plane. To reveal the correlation between atomic configurations of metallic and non-metallic elements and the MCA, we investigated the orbital magnetic moments projected onto structurally anisotropic d orbitals and the spin-conserving terms. The d orbitals extended in the plane perpendicular to the magnetization direction play a significant role in the MCA. Except for Fe in CFS(001), the orbital magnetic moments projected onto these orbitals are large. As a result, they change significantly under strain and contribute to the MCA. In contrast, Fe in CFS(001) is coordinated by Si atoms within the (100) and (010) planes, which suppresses these orbital magnetic moments and the contributions to the MCA. This correlation between atomic configurations and the MCA holds promise as a new design principle based on crystal structures and plane orientations. Furthermore, for CFS(422), the orbital magnetic moment and the \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{\downarrow \downarrow }\) from Co changes more significantly when magnetization aligns perpendicular to the strain. In contrast, those from Fe change more when magnetization are parallel.

Methods

First-principles calculations were performed based on density functional theory (DFT)116,117 by using pseudopotentials and pseudoatomic orbitals, as implemented in the OpenMX code118. We used the generalized gradient approximation for the exchange-correlation functional119,120. The basis sets of the s3p2d2 configuration were adopted for Co and Fe, while the s2p2d1 configuration was adopted for Si. To describe the structural and electronic properties, we employ the DFT + U method with effective Hubbard repulsion Ueff = U − J as 2.5 and 2.6 eV for Fe and Co 3d states, respectively25,26,76,121,122. The k-point grids were set to 15 × 15 × 15 and 21 × 9 × 12 for CFS(001) and CFS(422), respectively. As for convergence criteria, the maximum forces on the unit cell were 10−4 Hartree Bohr−1,while the total-energy variation was set as within 10−8 Hartree in general. For ε[100] = ε[010] in CFS(001), where \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{[100]}={E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{[010]}\approx {E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{[110]}\), the total-energy variation was set as within 10−11 Hatree in order to accurately evaluate the energy difference.

Figure 1 shows the unit cells of unstrained L21-ordered Co2FeSi. We chose the 1 × 1 × 1 and \(\sqrt{2}/2\times \sqrt{3}\times \sqrt{6}/2\) unit cells, referred to as CFS(001) and CFS(422), respectively. For CFS(001), the [100], [010], and [001] directions are set as the a-, b-, and c-axes, while for CFS(422), the \([0\bar{1}1]\), \([1\bar{1}\bar{1}]\), and [211] directions are set. For both systems, strains εa and εb ranging from −2% to + 2% were independently applied along the a- and b-axes, respectively. We apply not only uniaxial but also biaxial strain. Here, εa = (a − a0)/a0 and εb = (b − b0)/b0, where a0 and b0 are the unstrained lattice constants. Under these constraints, the length of the c-axis was optimized to minimize the total energy.

We evaluated the energy arising from the SOC ESOC, the MCA energy EMCA, the orbital magnetic moments morb, and the anisotropy of the orbital magnetic moments Δmorb by including the SOC explicitly in the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian of DFT. The MCA energy is defined as a difference between \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}\). Here, \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{a}\) and \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{b}\) denote the energy arising from the SOC per atom with magnetization aligned along a- and b-axes, respectively. Δmorb is defined as \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}-{m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}\), where the orbital magnetic moment \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{a}\) and \({m}_{{\rm{orb}}}^{b}\) are defined in the same fashion. From the energy with magnetization aligned along the 〈100〉, 〈110〉, and 〈111〉 directions within the (001) and (422) planes, we determined the magnetization easy axis. We evaluated the energy \({E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}{\sigma }_{2}}\) and its anisotropy \({E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}{\sigma }_{2}}\) using second-order perturbation theory with respect to the SOC Hamiltonian, on the basis of DFT calculations without including SOC explicitly in the Kohn-Sham Hamiltonian25,26,94,98,100,103. The SOC constants were assigned as 4.6079 Ry for Fe and 5.8063 Ry for Co, respectively123. To evaluate the effect of strain on the MCA-related quantities \(y={E}_{{\rm{MCA}}},{E}_{{\rm{MCA}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}{\sigma }_{2}},{E}_{{\rm{SOC}}}^{{\sigma }_{1}{\sigma }_{2}},{m}_{{\rm{orb}}},\Delta {m}_{{\rm{orb}}}\), an ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was performed based on the following linear model: y = y0 + (∂y/∂εa)εa + (∂y/∂εb)εb. Here, y0 denotes the y of unstrained Co2FeSi. We quantitatively extracted the strain derivatives ∂y/∂εa and ∂y/∂εb via OLS regression.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Schmid, H. Multi-ferroic magnetoelectrics. Ferroelectrics 162, 317–338 (1994).

Chandra, P., Dawber, M., Littlewood, P. B. & Scott, J. F. Scaling of the coercive field with thickness in thin-film ferroelectrics. Ferroelectrics 313, 7–13 (2004).

Manipatruni, S., Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Beyond CMOS computing with spin and polarization. Nat. Phys. 14, 338–343 (2018).

Spaldin, N. A. & Ramesh, R. Advances in magnetoelectric multiferroics. Nat. Mater. 18, 203–212 (2019).

Maruyama, T. et al. Large voltage-induced magnetic anisotropy change in a few atomic layers of iron. Nat. Nanotechnol. 4, 158–161 (2009).

Wu, T. et al. Electrical control of reversible and permanent magnetization reorientation for magnetoelectric memory devices. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 262504 (2011).

Taniyama, T. Electric-field control of magnetism via strain transfer across ferromagnetic/ferroelectric interfaces. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 27, 504001 (2015).

Wang, W.-G., Li, M., Hageman, S. & Chien, C. L. Electric-field-assisted switching in magnetic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 11, 64–68 (2012).

Wang, W. G. & Chien, C. L. Voltage-induced switching in magnetic tunnel junctions with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 46, 074004 (2013).

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555–558 (2012).

Berger, L. Emission of spin waves by a magnetic multilayer traversed by a current. Phys. Rev. B 54, 9353 (1996).

Slonczewski, J. C. Current-driven excitation of magnetic multilayers. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 159, L1–L7 (1996).

Akerman, J. Toward a universal memory. Science 308, 508–510 (2005).

Khvalkovskiy, A. V. et al. Basic principles of STT-MRAM cell operation in memory arrays. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 46, 074001 (2013).

Kent, A. D. & Worledge, D. C. A new spin on magnetic memories. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 187–191 (2015).

Devolder, T. et al. Material developments and domain wall-based nanosecond-scale switching process in perpendicularly magnetized STT-MRAM cells. IEEE Trans. Magn. 54, 1–9 (2018).

Lee, A. et al. A dual-data line read scheme for high-speed low-energy resistive nonvolatile memories. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 26, 272–279 (2018).

Lin, I.-C., Law, Y. K. & Xie, Y. Mitigating BTI-induced degradation in STT-MRAM sensing schemes. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. (VLSI) Syst. 26, 50–62 (2018).

Pan, W. et al. Electrical-current-induced magnetic hysteresis in self-assembled vertically aligned La2/3Sr1/3MnO3: ZnO nanopillar composites. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 021401(R) (2018).

Varghani, A., Peiravi, A. & Moradi, F. Perpendicular STT_RAM cell in 8 nm technology node using Co1/Ni3(111)∣∣Gr2∣∣Co1/Ni3(111) structure as magnetic tunnel junction. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 452, 10–16 (2018).

Yoon, I. & Raychowdhury, A. Modeling and analysis of magnetic field induced coupling on embedded STT-MRAM arrays. IEEE Trans. Comput. -Aided Des. Integr. Circuit Syst. 37, 337–349 (2018).

Kim, K.-W., Park, B.-G. & Lee, K.-J. Spin current and spin-orbit torque induced by ferromagnets. npj Spintronics 2, 8 (2024).

Usami, T. et al. Giant magnetoelectric effect in an L21-ordered Co2FeSi/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3−PbTiO3 multiferroic heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 142402 (2021).

Fujii, S. et al. Giant converse magnetoelectric effect in a multiferroic heterostructure with polycrystalline Co2FeSi. NPG Asia Mater. 14, 43–45 (2022).

Yatmeidhy, A. M. & Gohda, Y. Strain-induced magnetic anisotropy in Heusler alloys studied from first principles. Appl. Phys. Express 16, 053001 (2023).

Yatmeidhy, A. M. & Gohda, Y. Magnetic-anisotropy modulation in multiferroic heterostructures by ferroelectric domains from first principles. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 25, 2391268 (2024).

Duan, C.-G., Jaswal, S. S. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Predicted magnetoelectric effect in Fe/BaTiO3 multilayers: ferroelectric control of magnetism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 047201 (2006).

Laukhin, V. et al. Electric-field control of exchange bias in multiferroic epitaxial heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 227201 (2006).

Eerenstein, W., Wiora, M., Prieto, J. L., Scott, J. F. & Mathur, N. D. Giant sharp and persistent converse magnetoelectric effects in multiferroic epitaxial heterostructures. Nat. Mater. 6, 348–351 (2007).

Lebeugle, D., Mougin, A., Viret, M., Colson, D. & Ranno, L. Electric field switching of the magnetic anisotropy of a ferromagnetic layer exchange coupled to the multiferroic compound BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 257601 (2009).

Liu, M. et al. Giant electric field tuning of magnetic properties in multiferroic ferrite/ferroelectric heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 19, 1826–1831 (2009).

Niranjan, M. K., Burton, J. D., Velev, J. P., Jaswal, S. S. & Tsymbal, E. Y. Magnetoelectric effect at the SrRuO3/BaTiO3 (001) interface: An ab initio study. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 052501 (2009).

Wang, K. F., Liu, J.-M. & Ren, Z. F. Multiferroicity: the coupling between magnetic and polarization orders. Adv. Phys. 58, 321–448 (2009).

Garcia, V. et al. Ferroelectric control of spin polarization. Science 327, 1106–1110 (2010).

Geprägs, S., Brandlmaier, A., Opel, M., Gross, R. & Goennenwein, S. T. B. Electric field controlled manipulation of the magnetization in Ni/BaTiO3 hybrid structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 142509 (2010).

He, X. et al. Robust isothermal electric control of exchange bias at room temperature. Nat. Mater. 9, 579–85 (2010).

Vaz, C. A. F. et al. Temperature dependence of the magnetoelectric effect in Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O3/La0.8Sr0.2MnO3 multiferroic heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 97, 042506 (2010).

Wu, S. M. et al. Reversible electric control of exchange bias in a multiferroic field-effect device. Nat. Mater. 9, 756–761 (2010).

Brandlmaier, A., Geprägs, S., Woltersdorf, G., Gross, R. & Goennenwein, S. T. B. Nonvolatile, reversible electric-field controlled switching of remanent magnetization in multifunctional ferromagnetic/ferroelectric hybrids. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 043913 (2011).

Skumryev, V. et al. Magnetization reversal by electric-field decoupling of magnetic and ferroelectric domain walls in multiferroic-based heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 057206 (2011).

Lahtinen, T. H. E., Franke, K. J. A. & van Dijken, S. Electric-field control of magnetic domain wall motion and local magnetization reversal. Sci. Rep. 2, 258 (2012).

Pantel, D., Goetze, S., Hesse, D. & Alexe, M. Reversible electrical switching of spin polarization in multiferroic tunnel junctions. Nat. Mater. 11, 289–293 (2012).

Lei, N. et al. Strain-controlled magnetic domain wall propagation in hybrid piezoelectric/ferromagnetic structures. Nat. Commun. 4, 1378 (2013).

Liu, M. et al. Voltage tuning of ferromagnetic resonance with bistable magnetization switching in energy-efficient magnetoelectric composites. Adv. Mater. 25, 1435–1439 (2013).

Cherifi, R. O. et al. Electric-field control of magnetic order above room temperature. Nat. Mater. 13, 345–351 (2014).

Heron, J. T. et al. Deterministic switching of ferromagnetism at room temperature using an electric field. Nature 516, 370–373 (2014).

Staruch, M., Li, J. F., Wang, Y., Viehland, D. & Finkel, P. Giant magnetoelectric effect in nonlinear Metglas/PIN-PMN-PT multiferroic heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 152902 (2014).

Wang, J. J. et al. Effect of strain on voltage-controlled magnetism in BaTiO3-based heterostructures. Sci. Rep. 4, 4553 (2014).

Bauer, U. et al. Magneto-ionic control of interfacial magnetism. Nat. Mater. 14, 174–181 (2015).

Franke, K. J. A. et al. Reversible electric-field-driven magnetic domain-wall motion. Phys. Rev. X 5, 011010 (2015).

Hu, J.-M. et al. Purely electric-field-driven perpendicular magnetization reversal. Nano Lett. 15, 616–622 (2015).

Shirahata, Y. et al. Electric-field switching of perpendicularly magnetized multilayers. NPG Asia Mater. 7, e198 (2015).

Molinari, A. et al. Hybrid supercapacitors for reversible control of magnetism. Nat. Commun. 8, 15339 (2017).

Peng, B. et al. Deterministic switching of perpendicular magnetic anisotropy by voltage control of spin reorientation transition in (Co/Pt)3/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3−PbTiO3 Multiferroic Heterostructure. ACS Nano 11, 4337–4345 (2017).

Zhong, G. et al. Deterministic, reversible, and nonvolatile low-voltage writing of magnetic domains in epitaxial BaTiO3/Fe3O4 heterostructure. ACS Nano 9558–9567 (2018).

Fujita, K. & Gohda, Y. First-principles study of magnetoelectric coupling at Fe/BiFeO3(001) interfaces. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 024006 (2019).

Kudo, K. et al. Great differences between low-temperature grown Co2FeSi and Co2MnSi films on single-crystalline oxides. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 1, 2371 (2019).

Hamazaki, Y. & Gohda, Y. Enhancement of magnetoelectric coupling by insertion of Co atomic layer into Fe3Si/BaTiO3(001) interfaces identified by first-principles calculations. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 233902 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Giant non-volatile magnetoelectric effects via growth anisotropy in Co40Fe40B20 films on PMN-PT substrates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 092401 (2019).

Costa-Amaral, R. & Gohda, Y. First-principles study of the adsorption of 3d transition metals on BaO- and TiO2-terminated cubic-phase BaTiO3(001) interfaces. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 204701 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Electric-field-driven non-volatile multi-state switching of individual skyrmions in a multiferroic heterostructure. Nat. Commun. 11, 3577 (2020).

Costa-Amaral, R. & Gohda, Y. Role of ferroelectricity, delocalization, and occupancy of d states in the electrical control of interface-induced magnetization. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 064014 (2021).

Meisenheimer, P. B. et al. Engineering new limits to magnetostriction through metastability in iron-gallium alloys. Nat. Commun. 12, 2757 (2021).

Qin, H., Dreyer, R., Woltersdorf, G., Taniyama, T. & van Dijken, S. Electric-field control of propagating spin waves by ferroelectric domain-wall motion in a multiferroic heterostructure. Adv. Mater. 33, 2100646 (2021).

Leiva, L. et al. Electric field control of magnetism in FePt/PMN-PT heterostructures. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 544, 168619 (2022).

Hisada, Y., Komori, S., Imura, K. & Taniyama, T. Interlayer coupling-dependent magnetoelastic response in synthetic antiferromagnets. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 222402 (2023).

Imura, K., Ishikawa, S., Komori, S. & Taniyama, T. Enhanced magnetic modulation at a border of magnetic ordering in La1−xSrxMnO3/batio3(100) heterostructure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 202402 (2023).

Murakami, Y. et al. Metastable Co3Mn/Fe/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 multiferroic heterostructures. J. Appl. Phys. 134, 224101 (2023).

Usami, T. et al. Converse magnetoelectric coupling coefficient greater than 10−6 s/m in perpendicularly magnetized Co/Pd multilayers on Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 570, 170532 (2023).

Okabayashi, J. et al. Strain-induced specific orbital control in a Heusler-alloy-based interfacial multiferroics. NPG Asia Mater. 16, 3 (2024).

Taniyama, T., Gohda, Y., Hamaya, K. & Kimura, T. Artificial multiferroic heterostructures - electric field effects and their perspectives. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 25, 2412970 (2024).

Manipatruni, S. et al. Scalable energy-efficient magnetoelectric spin–orbit logic. Nature 565, 35–42 (2019).

Hu, J.-M. & Nan, C.-W. Opportunities and challenges for magnetoelectric devices. APL Mater. 7, 080905 (2019).

Hu, J.-M., Li, Z., Chen, L.-Q. & Nan, C.-W. High-density magnetoresistive random access memory operating at ultralow voltage at room temperature. Nat. Commun. 2, 553 (2011).

Wurmehl, S. et al. Geometric, electronic, and magnetic structure of Co2FeSi: Curie temperature and magnetic moment measurements and calculations. Phys. Rev. B 72, 184434 (2005).

Kandpal, H. C., Fecher, G. H., Felser, C. & Schönhense, G. Correlation in the transition-metal-based Heusler compounds Co2MnSi and Co2FeSi. Phys. Rev. B 73, 094402 (2006).

Hamaya, K. et al. Estimation of the spin polarization for Heusler-compound thin films by means of nonlocal spin-valve measurements: Comparison of Co2FeSi and Fe3Si. Phys. Rev. B 85, 100404(R) (2012).

Kimura, T., Hashimoto, N., Yamada, S., Miyao, M. & Hamaya, K. Room-temperature generation of giant pure spin currents using epitaxial Co2FeSi spin injectors. NPG Asia Mater. 4, e9 (2012).

Yamada, A. et al. Magnetoresistance ratio of more than 1% at room temperature in germanium vertical spin-valve devices with Co2FeSi. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 192404 (2021).

Hamaya, K. & Yamada, M. Semiconductor spintronics with Co2-Heusler compounds. MRS Bull. 47, 584–592 (2022).

Huang, H.-L., Tung, J.-C. & Jeng, H. T. A first-principles study on the effect of Cr, Mn, and Co substitution on Fe-based normal- and inverse-Heusler compounds: Fe3−xYxZ (x = 0, 1, 2, 3; Y = Cr, Mn, Co; Z = Al, Ga, Si). Front. Phys. 10, 975780 (2022).

Kübler, J. First principle theory of metallic magnetism. Phys. B+C. 127, 257–263 (1984).

Dederichs, P. H., Zeller, R., Akai, H. & Ebert, H. Ab-initio calculations of the electronic structure of impurities and alloys of ferromagnetic transition metals. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 100, 241–260 (1991).

Galanakis, I., Dederichs, P. H. & Papanikolaou, N. Origin and properties of the gap in the half-ferromagnetic Heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. B 66, 134428 (2002).

Galanakis, I., Dederichs, P. H. & Papanikolaou, N. Slater-Pauling behavior and origin of the half-metallicity of the full-Heusler alloys. Phys. Rev. B 66, 174429 (2002).

Miura, Y., Nagao, K. & Shirai, M. Atomic disorder effects on half-metallicity of the full-Heusler alloys Co2(Cr1−xFex)Al: A first-principles study. Phys. Rev. B 69, 144413 (2004).

Ležaić, M., Mavropoulos, P., Enkovaara, J., Bihlmayer, G. & Blügel, S. Thermal collapse of spin polarization in half-metallic ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 026404 (2006).

Kübler, J., Fecher, G. H. & Felser, C. Understanding the trend in the Curie temperatures of Co2-based Heusler compounds: Ab initio calculations. Phys. Rev. B 76, 024414 (2007).

Sato, K. et al. First-principles theory of dilute magnetic semiconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1633 (2010).

Bruno, P. Tight-binding approach to the orbital magnetic moment and magnetocrystalline anisotropy of transition-metal monolayers. Phys. Rev. B 39, 865 (1989).

Wang, D.-s, Wu, R. & Freeman, A. J. First-principles theory of surface magnetocrystalline anisotropy and the diatomic-pair model. Phys. Rev. B 47, 14932 (1993).

Stöhr, J. & König, H. Determination of spin- and orbital-moment anisotropies in transition metals by angle-dependent X-ray magnetic circular dichroism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 75, 3748 (1995).

Stöhr, J. Exploring the microscopic origin of magnetic anisotropies with X-ray magnetic circular dichroism (XMCD) spectroscopy. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 200, 470–497 (1999).

van der Laan, G. Microscopic origin of magnetocrystalline anisotropy in transition metal thin films. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 10, 3239–3253 (1998).

van der Laan, G. Angular momentum sum rules for X-ray absorption. Phys. Rev. B 57, 112 (1998).

van der Laan, G. Magnetic linear X-ray dichroism as a probe of the magnetocrystalline anisotropy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 640–643 (1999).

Wu, R. & Freeman, A. J. Spin-orbit induced magnetic phenomena in bulk metals and their surfaces and interfaces. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 200, 498–514 (1999).

Torbatian, Z., Ozaki, T., Tsuneyuki, S. & Gohda, Y. Strain effects on the magnetic anisotropy of Y2Fe14B examined by first-principles calculations. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 242403 (2014).

Miwa, S. et al. Voltage controlled interfacial magnetism through platinum orbits. Nat. Commun. 8, 15848 (2017).

Nakamura, S. & Gohda, Y. Prediction of ferromagnetism in MnB and MnC on nonmagnetic transition-metal surfaces studied by first-principles calculations. Phys. Rev. B 96, 245416 (2017).

Yan, S. et al. Role of exchange splitting and ligand-field splitting in tuning the magnetic anisotropy of an individual iridium atom on TaS2 substrate. Phys. Rev. B 103, 224432 (2021).

Cinal, M. Magnetic anisotropy and orbital magnetic moment in Co films and Co/x bilayers (x = Pd and Pt). Phys. Rev. B 105, 104403 (2022).

Miura, Y. & Okabayashi, J. Understanding magnetocrystalline anisotropy based on orbital and quadrupole moments. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 34, 473001 (2022).

Liu, X. B., Ryan, D. H. & Altounian, Z. Constituent contribution to the magnetocrystalline anisotropy in Mn(Al1−xGax). AIP Adv. 13, 025309 (2023).

Koroteev, Y. M. et al. Strong spin-orbit splitting on Bi surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 046403 (2004).

Bode, M. et al. Chiral magnetic order at surfaces driven by inversion asymmetry. Nature 447, 190–193 (2007).

Heide, M., Bihlmayer, G. & Blügel, S. Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction accounting for the orientation of magnetic domains in ultrathin films: Fe/W(110). Phys. Rev. B 78, 140403(R) (2008).

Zhang, H., Lazo, C., Blügel, S., Heinze, S. & Mokrousov, Y. Electrically tunable quantum anomalous hall effect in graphene decorated by 5d transition-metal adatoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 056802 (2012).

Absor, M. A. U., Kotaka, H., Ishii, F. & Saito, M. Strain-controlled spin splitting in the conduction band of monolayer WS2. Phys. Rev. B 94, 115131 (2016).

Absor, M. A. U. et al. Defect-induced large spin-orbit splitting in monolayer PtSe2. Phys. Rev. B 96, 115128 (2017).

Absor, M. A. U. & Ishii, F. Intrinsic persistent spin helix state in two-dimensional group-IV monochalcogenide 𝑀𝑋 monolayers (𝑀=Sn or Ge and 𝑋=S, Se, or Te). Phys. Rev. B 100, 115104 (2019).

Itoh, T. Derivation of nonrelativistic Hamiltonian for electrons from quantum electrodynamics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 37, 159 (1965).

Autés, G., Barreteau, C., Spanjaard, D. & Desjonquéres, M.-C. Magnetism of iron: from the bulk to the monatomic wire. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 18, 6785 (2006).

Sakuraba, Y. et al. Giant tunneling magnetoresistance in Co2MnSi/Al−O/Co2MnSi magnetic tunnel junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 88, 192508 (2006).

Usami, T. et al. Converse magnetoelectric effect in epitaxial Co2MnSi/Pb(Mg1/3Nb2/3)O3-PbTiO3 multiferroic heterostructures. IEEE Trans. Magn. 58, 2501505 (2022).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Ozaki, T. Variationally optimized atomic orbitals for large-scale electronic structures. Phys. Rev. B 67, 155108 (2003).

Perdew, J. P. & Wang, Y. Accurate and simple analytic representation of the electron-gas correlation energy. Phys. Rev. B 45, 13244 (1992).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Tsuna, S., Costa-Amral, R. & Gohda, Y. Origin of anisotropic magnetoresistance tunable with electric field in Co2FeSi/BaTiO3 multiferroic interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 132, 234101 (2022).

Khosravizadeh, S., Hashemifar, S. J. & Akbarzadeh, H. First-principles study of the Co2FeSi(001) surface and Co2FeSi/GaAs(001) interface. Phys. Rev. B. 79, 235203 (2009).

Yanase, Y. & Harima, H. Lecture on fundamental solid state physics: spin-orbit interactions and electronic states in crystals (part 1). Solid State Phys. 46, 229 (2011).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by JST CREST (Grant No. JPMJCR18J1), MEXT DXMag (Grant No. JPMXP1122715503), JSPS KAKENHI (Grant No. JP24K01144). The calculations were partly carried out by using supercomputers at ISSP, The University of Tokyo, and TSUBAME4.0, Institute of Science, Tokyo.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.W. performed numerical calculations and analyzed the results. Y.G. conceived the idea, supervised the project, and aided in interpreting the results. R.W. and Y.G. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Watarai, R., Gohda, Y. Strain-induced magnetocrystalline anisotropy in L21 Co2FeSi: first-principles study. npj Spintronics 3, 50 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00116-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44306-025-00116-w