Abstract

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) exchanges with the central nervous system’s immediate environment and interfaces with systemic circulation at the blood-CSF barrier. CSF composition reflects brain states, contributes to brain health and disease, is modulated by circadian rhythms and behaviors, and turns over multiple times per day, enabling rapid signal relay. Mechanisms of how CSF elements change over circadian time and influence function can be harnessed for diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic intervention.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Time-of-day is a critical biological variable1. Dysfunction in circadian rhythms is associated with neurodegenerative diseases, including Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia (reviewed in ref. 2), and interventions to correct circadian disruptions in these disorders are attractive ways to relieve symptoms. Further, a number of neurologic conditions co-present with circadian disruptions, including hydrocephalus, autism spectrum disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Sleep disruption is integral to many of these neurologic conditions and is a diagnostic criterion for major depression, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalized anxiety, and other mood disorders11. Many of these neurodegenerative and neurologic disorders also show abnormal CSF components that serve as disease biomarkers3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. Thus, harnessing the circadian nature of the CSF system in health and disease is an intersectional field ripe for new discoveries with the potential to inform interventions for neurologic disease.

More than a century of investigations indicate that the CSF contains biomarkers for circadian rhythmicity and can relay diurnal signals to target brain tissues. CSF production robustly varies across the 24-h light–dark cycle as measured by MRI12. CSF distribution between brain parenchyma interstitial fluid, ventricles, and cervical lymph nodes also varies across the 24-h day13,14,15. CSF oscillations occur during sleep and wakefulness and are driven in part by neural activity both in humans and mice16,17,18. Classic CSF transfusion studies showed that CSF can carry circadian cues for drowsiness19,20 and satiety21, and experimental models indicate that diffusible factors released from the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus into the CSF may contribute to the circadian rhythmicity of locomotion22,23,24,25,26.

The brain’s SCN “master clock” is entrained by daily light–dark cycles27. While humans, macaques, and pigs are active during the light phase, other common laboratory animals like rodents can be diurnal, nocturnal, or crepuscular28,29,30. Under laboratory conditions, common laboratory rat strains and laboratory mice, including C57BL/6, sighted C3H (corrected rd1 mutation and melatonin competent31), and CD1, are primarily active in the first half of the dark phase, and many are characterized as crepuscular. These distinct periods of activity require careful interpretation of results from such laboratory animals and indicate a need to correlate any findings from different temporal behavior patterns with diurnal animals or human samples before proceeding with therapeutic recommendations.

Importantly, daily rhythmic changes can be influenced by discrete time-of-day inputs or the interaction among these timekeeping signals. Thus, entrainment to the day includes photic entrainment (i.e., the light clock) and non-photic entrainment cues, like the molecular clock or behavioral clocks that include activity and feeding cues. The molecular clock keeps time at the cellular level and dominates in the absence of photic entrainment30. In mammals, the molecular clock is a negative feedback loop in which a heterodimer of the master circadian regulator BMAL1 and its partners CLOCK (or NPAS2) activate transcription of clock-controlled genes, including Period (Per) and Cryptochrome (Cry) that code for repressors of BMAL1 heterodimer activity, thus closing the loop that generates rhythms of approximately 24 h32,33. The light clock is the SCN of the hypothalamus. The SCN is entrained by daily light–dark cycles, and SCN output includes circuits and release of neuropeptides that communicate this light information to the rest of the body23,24,34. Finally, behavioral input, including locomotion, stress, and feeding, can modulate metabolism and shift or disrupt daily rhythms35,36.

Progress toward understanding bi-directional daily CSF regulation and signaling remains an active field of study (previously reviewed in refs. 37,38,39,40,41). However, because of the diagnostic and treatment capacity of CSF, the goal of this review is to characterize the actions, dynamics, and composition of this biofluid as a promising way to better understand the interactions between circadian rhythms and central nervous system (CNS) function and health.

Overview of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) system

CSF

CSF is an aqueous solution of ions (Na+, Cl−, K+, Ca2+, Mg2+, HCO3−), glucose, metabolites, proteins, neurotransmitters, cytokines, nanovesicles, and hormones (including thyroid hormone, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), serotonin (5-HT), melatonin, insulin, leptin, ghrelin, and cortisol). Its traditionally assigned roles include providing a buoyant fluid cushion and pH and ion balance for the CNS. CSF also plays critical roles in regulating the CNS throughout life, including the distribution of essential health and growth-promoting factors42,43,44,45,46,47. It also removes waste byproducts that reflect CNS state and have, therefore, been harnessed as disease biomarkers for conditions including injury like traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, metastasis, degenerative diseases (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease), neurological diseases (autism spectrum disorders, schizophrenia), and neuroinflammation. Although there is not free exchange between CSF and the interstitial fluid of the brain parenchyma in adulthood48 or during brain development49,50, these compartments do exchange solutes. This exchange happens in a diffusion-limited way at the ependyma ventricular surface in adult brains and along permissive routes, including perivascular spaces, white matter tracts, and subependymal spaces perivascular spaces after they mature51. Perivascular exchange of solutes between CSF and parenchyma is well-characterized52,53,54, although directionality, especially dominant parenchymal CSF outflow routes, and the question of convective flow through the parenchyma remains under active study51,55. One hypothesis proposes a glymphatic system of directional CSF influx along perivascular spaces lined by astroglial endfeet with polarized aquaporin4 (Aqp4) expression, directional parenchymal convective flow, and venous clearance. The polarized Aqp4 expression is implicated as a critical component of glymphatic exchange and reduction in this expression reduces solute eliminate rates between CSF and brain parenchyma55,56. Why Aqp4 reduces parenchymal solute clearance remains an active field of study. Further, brain solutes that originate in parenchyma are found in lymph nodes prior to entering the blood, implicating multiple routes of parenchymal solute clearance. Continuing to generate a more complete understanding of CSF exchange with brain parenchyma and solute efflux is important to a holistic model of CSF circadian rhythmicity, as parenchymal solute clearance rates and CSF solute parenchymal influx rates do change with respect to time of day and activity15,18,41,57,58.

Choroid plexus

Choroid plexus tissues are located in each of the four brain ventricles, or cisterns—two lateral ventricles, the 3rd ventricle, and the 4th ventricle (Fig. 1A). Transcriptomics from mouse has identified molecular differences among lateral ventricle choroid plexuses vs. 3rd ventricle choroid plexus, vs. 4th ventricle choroid plexus59, but the overall structure is similar. Choroid plexus is a specialized tissue of neural origin whose structure includes fenestrated capillaries interfacing with a fibroblast and mesenchymal core that is surrounded by a monolayer of specialized epithelial cells with highly articulated CSF-facing apical structures, including microvilli and tight junctions at the apico-lateral interface. These tight junctions, along with polarized transporters and enzymes, form the blood-CSF barrier that actively regulates exchange between CSF and systemic circulation. The choroid plexus also contains resident immune cells, including macrophages, T cells, B cells, and Th17 cells. During immune challenge, the choroid plexus can become populated by neutrophils and other markers of inflammation60,61, including barrier changes like closing endothelial fenestrae after inflammation in the adult gut62. Choroid plexus epithelial cells (Fig. 1A) exhibit a very high apical surface area for interacting with the CSF63 and these epithelial cells are highly energetic/ metabolically active. They contain a cohort of ion and water channels64, detoxifying transporters65,66,67, and apparatus for vesicular transport and paracrine/apocrine signaling59,68,69. Of potential relevance for daily signaling, choroid plexus epithelial cells of the mouse lateral ventricle choroid plexus are depleted for insulin signaling compared with 3rd and 4th ventricle choroid plexus tissues, with lower expression of Ins2 than the other two tissue types59,70,71; and 4th ventricle choroid plexus epithelial cells express neuropeptides like endogenous opioid proenkephalin (Penk) that are not expressed by the lateral or 3rd ventricle choroid plexus tissues59. These examples of key differences among choroid plexus tissues reinforce the importance of treating each choroid plexus tissue separately when measuring diurnal changes and functions. Changes in choroid plexus epithelial cell barrier, ion transport, enzyme expression, or secretion apparatus are key elements that can change CSF composition. Thus, the choroid plexus regulates CSF composition both through its barrier and secretory roles. The choroid plexus is also innervated by the sympathetic, parasympathetic, cholinergic, and peptidergic systems, which have been shown to contribute to regulating CSF production or composition in mammalian models72,73,74. Since the autonomic nervous system coordinates circadian functions throughout the body75, this innervation is likely upstream of some choroid plexus daily changes. Since the choroid plexus plays discrete key roles in CNS health, fluctuations in choroid plexus CSF production, solute secretion, or barrier functions are likely the most important to consider when including it in a discussion of the circadian system.

Circumventricular organs and tanycytes

Circumventricular organs are midline structures contacting the ventricular system that are open to neuro-hemal exchanges largely for endocrine purposes. They include the median eminence, organum vasculosum, laminae terminalis, subfornical organ, subcommissural organ, pineal gland, and area postrema76. These organs can directly impact CSF composition and even dynamics, for example subcommissural organ ependymal cell cilia motility in response to CSF glucose can alter local flow rates and secrete Wnt5a-positive vesicles77 in rodents. In humans, the subcommissural organ is only present in fetuses and can be distinguished from 7 weeks to 5 months, playing the role of an active secretory structure into the CSF77,78. Some of the roles of the subcommisural organ in humans may be taken on by ependymal cells of the hypothalamic median eminence and choroid plexus77. Of key importance to the circadian system, the pineal gland is a neuroendocrine circumventricular organ where information about photoperiods and ambient temperature or food availability is transduced into the chemical signal, melatonin, which is observed in the CSF79. In the median eminence, tanycytes—specialized radial glial cells— line the third ventricle and regulate of broad range of hypothalamic functions80. The apical side of median eminence tanycytes harbors tight-junction complexes, thereby preventing the passage of blood-borne molecules into CSF. On the basal side, tanycytes contact fenestrated vessels in the median eminence and capillaries in neighboring hypothalamic nuclei81. Relevant to time-of-day signaling, insulin receptors in tanycytes of the mediobasal hypothalamus are necessary to regulate insulin access and control systemic insulin sensitivity82.

CSF dynamics and outflow routes

CSF is estimated to turn over ~every 5 h in humans and ~every 2 h in mice83,84,85, as calculated by total volume/production rate. But a third variable, CSF outflow, also contributes effective turnover. As CSF is produced, it moves throughout the brain ventricles, subarachnoid space, and spinal canal and is drained into the blood or extracranial lymphatic system84. Several putative CSF clearance routes include arachnoid villi and granulations in human (and only arachnoid villi in non-human mammalian species), perineural and perivascular pathways, and meningeal lymphatics44,55,86,87. It has been shown in rats, pigs, and sheep that lymphatic vessels contribute to CSF clearance by connecting with CSF around the cribriform plate and olfactory nerve roots during perinatal brain development88,89,90. Meningeal lymphatics play key roles in clearing CSF. In fact, CSF components, including cellular debris after injury, can be found in the cervical lymph nodes. Recently, roles of the pressure-sensitive Piezo1 channel have been identified to regulate meningeal lymphatic CSF clearance and the chemical agonist Yoda1 is sufficient to increase CSF outflow91,92. Other activities that change across the time of day including breathing, sleeping, and physical activity93 can impact CSF mixing and outflow in humans.

Development

The CSF system functions distinctly as it matures. Since the adult mechanisms of generation and outflow only arise later in development, other processes govern this system early. CSF composition is quite distinct in early development with protein46,47,94 and ion compositions95,96,97 maturing throughout development. CSF composition governs some of the active roles of the CSF in maintaining early brain health. For example, the unique composition of proteins like growth factors and morphogens46,47,98,99,100,101,102, neurotransmitters71,103,104,105, nanovesicles/endosomes106,107,108,109,110, non-coding RNA106,107,111, metabolites112, and hormones112 confer CSF the ability to maintain developing neural progenitors. Further, CSF composition can reflect key brain developmental stages, as CSF proteins match the changing gene expression of normal early CNS parenchymal development113,114. The CNS developmental timeline informs which CSF components are present and how they mature as the brain develops. CSF arises after neural tube closure (~E9 in mice), and the brain ventricles begin to form and develop. Meninges also interact with CSF and are present early (~E8 in mice) and mature later (~birth in mice)115. Choroid plexus begins to emerge after CSF is detectable (~E11 in mice) and continues maturing its ability to transport ions and other functions during the first postnatal weeks44,59,96,102,116,117,118. Perivascular components begin to arise with endothelial tight junctions emerging as the choroid plexus matures (~E12 in mice) and blood-brain barrier function is evident at E15.5119. Ependymal cells that line the mature brain ventricles are generated by radial glia beginning at E14 in mice and mature around P5 to display fully functional motile multi-cilia120. The arachnoid barrier is formed by E17 in mice121, but the precise developmental functional timeline of arachnoid villi and their relative contribution to CSF outflow remains less clear. The larger arachnoid granulations are not recognized in rodents. In humans, they appear after 39 gestational weeks they are not fully formed until 2 years of age122. Meningeal lymphatic vessels sprout from existing vessels at the base of the skull around E18 or birth in mice, and this system continues to mature throughout the first postnatal month115. Maturation and polarization of perivascular astrocytes, including the hindfoot-basal lamina junctional complex and Aqp4 (implicated in the glymphatic model) occur ~P7 in mice123, after the arachnoid barrier forms, and mature perivascular CSF infiltration and parenchymal exchange emerge by P14 in mice124. As natural aging proceeds, changes to CSF composition94,125, CSF production and turnover126, choroid plexus function59,127, meningeal lymphatics87, glymphatic exchange56, and other systems begin to occur. Whether these changes with aging are affected by or impact the overall reduction in circadian regulation observed with ageing128 remains an important open question.

Daily rhythms of CSF solutes

As highlighted above, CSF solutes are complex and dynamic (Fig. 1B). They can arise from multiple source tissues, be the result of CNS waste clearance, brain barrier function, or actively regulated transport, detoxification, or secretion processes. The production of some diurnally regulated CSF solutes cycle in their source tissues including cortisol production by peripheral adrenal glands, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) release by hypothalamus and melatonin from the pineal gland23,25,79,129,130,131. The light-entrained SCN pacemaker can interact directly with the CSF through release of diffusible factors26. The SCN diurnally releases vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP), arginine vasopressin (AVP), and gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) which can be observed cycling in CSF. Lesioning the SCN abolishes the orexin A (hypocretin-1) concentration rhythmicity in CSF132,133. Further, the caudal dorsal raphe of the hypothalamus maintains serotonergic axons that directly reach the CSF in both nocturnal and diurnal animals73,74. Using a fluorescently tagged cholera toxin beta subunit retrograde tracer injected into the CSF of nocturnal and diurnal animals, the location and pattern of labeling was localized in the hypothalamus to the cluster of serotonergic neurons in the caudal dorsal raphae in both subtypes134. This consistency between diurnal and nocturnal model organisms suggests that it is the downstream interpretation of these dorsal raphe-to-CSF serotonergic signals that are modified for the differential needs of diurnal vs. nocturnal animals rather than this circuitry itself.

Other key CSF solutes, like thyroid hormones, show diurnal differences in CSF concentrations that correspond with systemic thyroid hormone and the expression of CSF thyroid hormone carrier protein transthyretin (TTR) in choroid plexus135. Modulating systemic thyroid hormone has recently been implicated in coordinating thyroid hormone gene programs that drive daily behavioral changes, including feeding and exploratory behavior136, with the potential to directly interface with CSF thyroid hormone and thyroid hormone transport into the CSF as regulated by choroid plexus transporters and carriers135. Further, circadian variations in metabolism induce differential CSF metabolites135,137. The CSF and choroid plexus both reflect a more oxidative signature during the active phase135. Modulating brain interstitial ions has been shown to alter sleep-wake state138, opening the possibility of functional roles of CSF ions throughout the day. Studies of human and animal CSF ions find that CSF K+, Na+, and Cl− decrease during sleep phases138,139,140 and can change during seizure activity140. While CSF Na+ and Cl− remain at intermediate concentrations during sleep deprivation, CSF K+ is low both during healthy sleep and during wakeful sleep deprivation139, suggesting a circadian, rather than sleep, induced modulation of CSF K+, which may reflect any combination of choroid plexus ion modulation, neuronal activity, and glial K+ buffering.

Because solute concentrations in fluids like CSF are dependent on dilution, there is the possibility that the observed cycling of CSF protein or ion levels is an emergent property of fluid production dynamics. However, this is not the case for all solutes because CSF solute cycling peaks and nadirs are specific to select solutes. For example, no significant circadian fluctuations were found in CSF levels of klotho, a key CSF component141 or other CSF ions like calcium or magnesium. Thus, it is a reasonable conclusion that circadian rhythms of individual CSF solutes are actively regulated and reflect specific changes in the CNS, act as key functional signaling components of CNS circadian output, or both.

Daily rhythms of CSF volume and pressure

Daily changes in human CSF dynamics were first observed by Nilsson12 who measured CSF production by magnetic resonance imaging of net CSF flow through the cerebral aqueduct at distinct circadian times (Fig. 1B). In this study, the average CSF production in six healthy volunteers indicated circadian variation, with minimum production at 6 p.m. of ~12 mL/h which was ~30% of the maximum observed values at a nightly 2 a.m. peak with production of ~42 mL/h. These findings were corroborated in an independent set of intensive care unit patients over 30 years later142. In Sprague-Dawley rats, a 30% increase in intracranial pressure was observed during the night, which is the active phase for these rodents142. These findings of peak CSF production/pressure at orthogonal phases of activity in humans and rats raise the possibility of independent control of CSF pressure (perhaps by light-based clocks) versus CSF metabolites, which were more alike at equivalent active phases (perhaps by feeding). Further, Sprague-Dawley rats are crepuscular rather than nocturnal, so the daily activity differences between these models and humans may further complicate the comparisons between light vs. dark phases, active vs. rest phases, or sleep vs. wake periods. This study also suggests that the daily increase in intracranial pressure is independent of vascular parameters142 that could influence the perivascular CSF influx57 that changes between day and night14,15 and after sleep deprivation18,143,144. Together, these findings indicate that circadian rhythms of CSF volume and pressure may be at least partially independently regulated from the circadian rhythms of parenchymal CSF influx.

The mechanisms of circadian changes to CSF volume or intracranial pressure are still under investigation. Such changes could be downstream of activity-dependant buildup of solutes in the interstitial fluid that, when cleared, drives water into the CSF system through osmosis. It could also be more specifically regulated by glucocorticoids, whose levels cycle over circadian times and can increase intracranial pressure in rat models145. Observed changes in CSF dynamics may also be directly driven by the choroid plexus, which is specialized to secrete CSF in adults through ion transport and water secretion. The rhythmic cycling of both expression and activation of the carboxylic anhydrase (CAII) in the choroid plexus has been observed in rats with a drop in activity during the light phase146, and this rhythm could alter CSF secretion. Carbonic anhydrases enzymatically convert HCO3− and H+ from H2O and CO2, and while they are not directly involved in ion transport, they have important roles in CSF secretion as carbonic anhydrase expression is a key event in early choroid plexus differentiation147. While a slight rhythm for the major apical water transporter on choroid plexus epithelial cells, aquaporin1 (Aqp1), has been reported in some systems, Aqp1 is likely not robustly regulated at the circadian level in rodents135,148. Therefore, the major drivers of these circadian changes in CSF dynamics remain to be defined.

Daily rhythms of choroid plexus

Cycling elements of the molecular clock have been identified in all mature tissues in the body where they have been investigated149,150,151, including the major CSF-producing tissue, the choroid plexus135,152,153. Each molecular clock in the body responds to systemic synchronizing cues, however the peak phases of these rhythms vary among individual brain tissues and the periphery, which, in turn, differ between diurnal and nocturnal animals154. These circadian cycles include general and tissue-specific changes in the choroid plexus. Since the choroid plexus has some rhythmic gene expression elements throughout the day, validated stable (non-cycling) gene products like beta actin (Actb) and hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (Hprt1) represent important reference genes when normalizing circadian data in these tissues155.

One of the earliest reports of rhythms in the choroid plexus is the observation of circannual (seasonal) rhythmicity in the antidiuretic effect of choroid plexus extracts (elevated in Sept–Dec), vesicle load (elevated in winter), and the glycogen load/mitochondria abundance (elevated in winter) in toads (Bufo bufo) in the U.K.156. Further, choroid plexus shows a striking rhythmic seasonal pattern of activation (by c-fos expression) in a hibernating squirrel—the thirteen-lined ground squirrel157. With strong c-fos activation reported in choroid plexus epithelial cells and 3rd ventricle tanycytes that peaks as arousal from hibernation initiates. In arousal, c-fos activity in choroid plexus epithelial cells diminishes along with diminished activity in SCN and reticular thalamic nuclei, however activity in ependymal cells increased during the arousal phase, indicating complex independent regulation of choroid plexus from other ventricular structures throughout these hibernation cycles157.

Circadian clock gene expression in the choroid plexus was observed in a study investigating the effects of sex hormones on the choroid plexus by microarray on male and female sham vs. gonadectomized mice. This study identified significant changes in clock genes among these populations158. In light of these observations, circadian findings in the choroid plexus were expanded to better understand roles of sex hormones on choroid plexus rhythmicity159, finding that choroid plexus rhythmicity is modulated by estrogens153. Ex vivo choroid plexus circadian rhythmicity is sensitive to exogenous application of a synthetic glucocorticoid analog (dexamethasone) both when applied ex vivo135 or in vivo160. In animals lacking glucocorticoids (corticosteroids that bind to the glucocorticoid receptor) due to the removal of adrenal glands, the rhythmicity of Per1, Per2, Nr1d1, and Bmal1 expression in choroid plexus were all dampened161 and conversely rhythmic administration of dexamethasone reinforced these transcriptional rhythms in choroid plexus161. Sex hormones and glucocorticoids are broadly implicated in both choroid plexus function and CSF homeostasis88,145,162. Indeed, the circadian choroid plexus response to both sex hormones and glucocorticoids remains one of the more deeply studied aspects of choroid plexus circadian rhythmicity.

The developmental timing of this rhythmicity emergence in rodents was investigated using a Per2-Luciferase mouse135,152,163 and in rats162. Stable exogenous choroid plexus Per2 rhythmicity is evident at birth in mice, but the zenith and nadir remain desynchronized between young animals and the period is variable. Per2 rhythmic expression synchronizes across animals to a 24-h oscillation period around P11152. Choroid plexus circadian rhythmicity results in substantial changes in protein translation, including secreted proteins, mitochondrial proteins, and barrier components135. These cycles in protein expression correlated with altered choroid plexus secretome, metabolome, and barrier structure. Diurnal rhythms in choroid plexus transcription have been observed in rats that are consistent with metabolic and secretome changes shown in mouse137. Further detailed analysis of coordinated choroid plexus rhythmic gene expression classified suites of gene expression with the predominance of peaks around CT17-21 and other sets of genes that peak in expression around CT8-15160. The core clock component Bmal1 and feeding cues mediate choroid plexus rhythmicity135,152, and intact SCN activity is required for choroid plexus diurnal translation responses135 and circadian gene expression160. Melatonin is synthesized by porcine choroid plexus explants, although no circadian pattern has been observed in choroid plexus melatonin synthesis164. However, melatonin can reset the choroid plexus circadian clock in an immortalized cell line derived from primary rat choroid plexus epithelial cells (Z310 cells)165. In contrast, choroid plexus circadian rhythmicity has been shown to be resistant to lipopolysaccharide immune challenge, which dampens, but does not abolish, rhythmicity in the choroid plexus, unlike the strong supression of the liver circadian clock in response to immune challenge166.

Functional assays of choroid plexus circadian roles remain an open field of study. Circadian changes in transporter function can regulate transport across an in vitro model of the choroid plexus barrier167,168. Co-culture of choroid plexus and SCN implicate a factor secreted by the choroid plexus that can influence SCN rhythmicity, but whose identity is not yet elucidated152. After removing core clock component Bmal1 from the choroid plexus and other multiciliated cells using the Foxj1-cre mouse line, large-scale diurnal changes in choroid plexus translation were observed along with altered CSF contents and disruptions in diurnal behaviors104. However, in a different mouse model with a substantial reduction of the choroid plexus in adults—the ROSA diphtheria toxin receptor (DTR) mouse line—no circadian behavioral disruptions are observed169, indicating that the behavioral disruptions observed after Foxj1-cre induced Bmal1 conditional loss of function are either due to non-choroid plexus functions, differences in mouse lines, or are compensated for in the DTR model. Laboratory approaches that specifically modulate the choroid plexus in vivo to enable circadian behavioral readouts remain under development170, but harnessing the viral tropism of AAV2/5 or developing new transgenic lines that are specific to the tissue will be crucial to advancing this field that ultimately requires integrated whole body readouts.

Implications of daily rhythms in the CSF system for chronopharmacology and disease

The blood-brain barrier and blood-CSF barrier are key considerations for successful pharmaceutical targeting to the CNS because they limit access of systemic substances to the CNS. While the blood-brain barrier has been increasingly studied, detailed knowledge of the blood-CSF barrier and the cell types involved in both of these barriers remain less-well understood (Fig. 2). The blood-brain barrier is regulated at the level of cerebral vasculature, pericytes, and astrocytic endfeet sealed by tight junctions and low rates of transcytosis. The choroid plexus maintains the blood-CSF barrier, bridging systemic circulation to the CSF, through tight junctions at the apical aspect of epithelial cells, transcytosis, active transport, metabolism135, and regulation of endothelial fenestration62. Both of these brain barriers change across time-of-day, although even less is known about the circadian responses in these barrier functions and their cellular components (Fig. 2). Therefore, considering daily change in these barriers will be key for access and control over brain borders, including actively bypassing them, as a goal of pharmacology171,172.

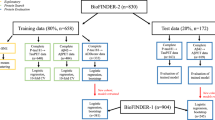

Despite large increases in studies about CSF (A) and circadian systems (B), only the blood-brain barrier is deeply studied at the intersection of systemic circulation, the brain, and circadian rhythms (C, D). This emphasis on blood-brain barrier overshadows choroid plexus, blood-CSF barrier, and cellular components of the blood-brain barrier like cerebral vasculature. Thus, representing a scientific opportunity to increase the study of the CSF system across diurnal changes. Search terms on PubMed of “cerebrospinal fluid,” “circadian,” “blood brain barrier,” “choroid plexus,” blood CSF barrier,” “cerebral vasculature,” “blood brain barrier + circadian,” “choroid plexus+ circadian,” blood CSF barrier+ circadian,” “cerebral vasculature+ circadian.” Data exported 4 September 2024 and plotted until 2023.

Inherent variation across the day in the blood-CSF barrier have been identified at the level of tight junctions, drug transport, and metabolism. In mice, tight junctions at the apical aspect of choroid plexus epithelial cells widen during the rest phase and pull epithelial membranes tighter together during the active phase, which correlated with changes in gene expression of barrier-associated genes like integrins, cadherins, and sorting nexins135. Further, drug transporters may also be differentially expressed across the day like ABCC4 (MTX transporter)168 and ABCG2 (Donepezil transporter)167. Other diurnally regulated transporters may interact with pathogens or toxins like ABCF3 (flavivirus antiviral transporter) and SLC7A8 (thyroid hormone and methylmercury transmembrane transporter)135. The daily change in choroid plexus metabolic processes, including an increase in oxidative metabolism during the active phase135, can interface with both ATP-dependent active transport across the barrier and drug pharmacology. More broadly, metabolism and mitochondrial function are disrupted in the brains of individuals at high risk for psychosis173,174 and altered bioenergetics profiles are hallmarks of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease175, suggesting broad overlap in daily metabolism change and long-term brain health. Aβ uptake capacity of the choroid plexus may also depend on appropriate daily cycling as rhythmicity is observed in genes or gene products that interface with amyloid-β (Aβ), including ACE and TTR135,176, and apolipoprotein J and gelsolin177. Increased CSF Aβ during sleep deprivation in healthy middle-aged adults has been shown to be dependent on sleep disruption and not due to stress or a more general circadian disruption178. Cycling Aβ uptake was observed in a human choroid plexus papilloma cell line that was incubated with Aβ-488176 and FACS purified across 24 h, although direct measures of choroid plexus Aβ uptake across the day remain to be measured in vivo. Further, in the Alzheimer’s model (APP/PS1), choroid plexus Per2 rhythmicity has been shown to change in some rodents (year-old males), but not in others (females, young males) or even in other core circadian gene expression like Cry2165, so the effects of Alzheimer’s disease and CSF Aβ on choroid plexus rhythmic gene expression and function remain an active field of study.

Pharmaceutical interventions can also directly change the circadian rhythms of the choroid plexus and brain ventricular system. As noted earlier, dexamethasone can resynchronize the choroid plexus molecular clock135,160,161. Anesthetics interface with diurnal behaviors, including arousal and diurnal processes in the brain like the CSF exchange with brain parenchyma or clearance of brain tracers to the periphery that are implicated in glymphatic function58,179,180. Sevoflurane is an inhaled anesthetic that induces hypnosis, amnesia, analgesia, akinesia, and autonomic blockade. When sevoflurane is administered to animals, changes in choroid plexus Per2 rhythmicity, but not SCN Per2 rhythmicity, were observed181 by explant readouts from Per2-Luciferase mice. Intriguingly, this shift was detectable up to 30 days after treatment, indicating long-term modulation of choroid plexus rhythmicity181. When LiCl was applied to choroid plexus explants, it delayed the in vitro circadian clock phase and prolonged the period, circadian disruptions that were opposite from those observed after CHIR-99021 (a glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor) application182. The LiCl-induced phase delay and period lengthening were lessened by the additional application of chelerythrine (a protein kinase C (PKC) inhibitor), suggesting a PKC-involved mechanism182. Thus, attention to time of day is recommended when administering circadian-disrupting drugs at the brain CSF barrier, like dexamethasone, LiCl, or anesthetics.

Conclusions and open questions

From the experiments inducing behavioral changes by transplanting CSF between sleep-deprived or food-restricted animals over 100 years ago, the CSF system is emerging anew as a critical component of daily brain health and function. Our ability to understand daily changes in this system is growing as modern tools emerge like CSF fiber photometry135 and intravital choroid plexus imaging183 enable real-time monitoring CSF and choroid plexus in animal models coupled with the availability of large-scale sequencing. The daily changes summarized here that have been observed in CSF composition, CSF volume/pressure, choroid plexus activity, and brain barrier permeability and metabolism solidify the CSF system as a key circadian element.

The field remains very active and key open questions remain as to both upstream influences on the rhythmicity and downstream functions of rhythmic components of the CSF system. For example, any observation of diurnal changes does not always implicate true circadian rhythmicity— thus, functional dependence on light cues and the molecular clock should be validated for diurnal observations. This question of true circadian rhythmicity and entrainment stimuli is important for intervention, as the answer to it provides details on how best to manipulate the system in disease or to harness CSF for drug delivery. Some signals, like CSF TTR have been shown to continue to cycle in total darkness for multiple days and in ex vivo explants135, however this isn’t the case for all diurnal components of the CSF system and activity, feeding, hormones, and sleep can all interact with and tune the system. Some studies have begun to separate these components by removing Bmal1135,152, lesioning the SCN160, modulating hormones153,159, inverting feeding times135, measuring changes that continue in the dark135,152, and comparing CSF pressure between diurnal humans and crepuscular rodents142. The challenge of metabolism, in particular, is complex as it can directly interact with mechanisms of active transport due to its influence on ATP availability and direct interface with translation184. New studies should continue to work to separate sleep, the cellular clock, feeding, activity, and light cues when reporting daily changes in CSF and choroid plexus properties so that interventions that take advantage of the blood-CSF barrier or CSF production/clearance can be appropriately timed to extrinsic cues. Modulation of diet, light exposure, or activity could enhance pharmacologic interventions, as has been shown relevant for immunology, cancer progression, and cognition (e.g., refs. 2,185).

Further, additional functions ascribed to the CSF system, including the CSF solutes that support the developing and adult neural stem cell niches, are likely to be affected by circadian rhythmicity. Age-dependent differences in circadian regulation of the CSF system, from the inception of CSF rhythmicity to natural aging, likely respond to the developing and aging body clock and may contribute to changes in neurological function across the lifespan. The reduced CSF production associated with aging126 could, for example, result from overall lessened circadian regulation with age. The crossover of brain development and aging, including brain stem cells, with circadian regulation could inform regenerative strategies and complement the understanding of the cognitive effects of circadian disruption.

Continued collaboration among circadian experts, those in the brain borders fields, and clinicians is critical for the rigorous study of circadian changes in the interfaces between the brain and systemic rhythmicity. Large-scale human studies of CSF imaging via MRI, CSF component analysis (like harnessing time stamps from emergency department visits with banked CSF from lumbar puncture), and analysis of postmortem choroid plexus or CSF samples with time-of-day information will further enable more translational conclusions from controlled studies in models, including identifying common principles among model organisms with diverse photic periods28,29,30. The most critical functions of the choroid plexus and CSF system, including CSF production and turnover, solute control like release of factors that support the brain or clearance of waste products, and maintenance of the blood-CSF barrier are crucial to understand from the perspective of circadian rhythms.

Ultimately, considering the circadian nature of the choroid plexus and CSF system complements current efforts to harness this system for therapeutic intervention. For example, harnessing natural daily variation in the blood-CSF barrier could aid efforts to time approaches that bypass the blood-CSF or blood-brain barrier for drug delivery186,187,188. Further, approaches that target gene therapy to the blood-CSF barrier, e.g., AAV transduction of ependymal or choroid epithelial cells, which has been shown to improve neurologic symptoms in rodent models of Huntington’s disease, lysosomal storage disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease189,190,191,192, could restore any circadian functions that are ultimately determined to be key for behavioral readouts. In addition to restoring healthy circadian function, the ability of the choroid plexus to secrete proteins into the CSF can be harnessed to restore CSF solute composition regardless of the endogenous source or to add metabolic function to neutralize toxins or locally convert an inactive prodrug to an active drug. While many correlates of CSF and choroid plexus with circadian rhythm have been determined as described here, the next frontier is functional evaluation of which of these molecular or radiological biomarkers are reporting circadian state vs. those that are controlling circadian output or brain phenotypes. Careful functional evaluation will then open the possibility of harnessing the choroid plexus and CSF system to both monitor circadian changes and intervene to restore or supplement function.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

Nelson, R. J., DeVries, A. C. & Prendergast, B. J. Researchers need to better address time-of-day as a critical biological variable. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2316959121 (2024).

Nassan, M. & Videnovic, A. Circadian rhythms in neurodegenerative disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 18, 7–24 (2022).

Poltorak, M. et al. Monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia are discordant for N-CAM and L1 in CSF. Brain Res. 751, 152–154 (1997).

Poltorak, M. et al. Increased neural cell adhesion molecule in the CSF of patients with mood disorder. J. Neurochem.66, 1532–1538 (1996).

Poltorak, M. et al. Disturbances in cell recognition molecules (N-CAM and L1 antigen) in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia. Exp. Neurol. 131, 266–272 (1995).

Mobarrez, F. et al. Microparticles and microscopic structures in three fractions of fresh cerebrospinal fluid in schizophrenia: case report of twins. Schizophr. Res. 143, 192–197 (2013).

Johansson, V. et al. Microscopic particles in two fractions of fresh cerebrospinal fluid in twins with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder and in healthy controls. PLoS ONE 7, e45994 (2012).

Walker, W. H. 2nd, Walton, J. C., DeVries, A. C. & Nelson, R. J. Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health. Transl. Psychiatry 10, 28 (2020).

Wulff, K., Dijk, D. J., Middleton, B., Foster, R. G. & Joyce, E. M. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in schizophrenia. Br. J. Psychiatry200, 308–316 (2012).

Wulff, K., Gatti, S., Wettstein, J. G. & Foster, R. G. Sleep and circadian rhythm disruption in psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 589–599 (2010).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Nilsson, C. et al. Circadian variation in human cerebrospinal fluid production measured by magnetic resonance imaging. Am. J. Physiol. 262, R20–R24 (1992).

Boespflug, E. L. & Iliff, J. J. The emerging relationship between interstitial fluid-cerebrospinal fluid exchange, amyloid-beta, and sleep. Biol. Psychiatry 83, 328–336 (2018).

Xie, L. et al. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. Science 342, 373–377 (2013).

Hablitz, L. M. et al. Circadian control of brain glymphatic and lymphatic fluid flow. Nat. Commun. 11, 4411–4411 (2020).

Fultz, N. E. et al. Coupled electrophysiological, hemodynamic, and cerebrospinal fluid oscillations in human sleep. Science 366, 628–631 (2019).

Williams, S. D. et al. Neural activity induced by sensory stimulation can drive large-scale cerebrospinal fluid flow during wakefulness in humans. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002035 (2023).

Jiang-Xie, L. F. et al. Neuronal dynamics direct cerebrospinal fluid perfusion and brain clearance. Nature 627, 157–164 (2024).

Ishimori, K. Sleep-inducing substance(s) demonstrated in the brain paranchyma of sleep-deprived animals—a true cause of sleep. Tokyo Igakkai Zasshi 23, 429–457 (1909).

Pappenheimer, J. R., Miller, T. B. & Goodrich, C. A. Sleep-promoting effects of cerebrospinal fluid from sleep-deprived goats. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 58, 513–517 (1967).

Martin, F. H., Seoane, J. R. & Baile, C. A. Feeding in satiated sheep elicited by intraventricular injections of CSF from fasted sheep. Life Sci. 13, 177–184 (1973).

Carmona-Alcocer, V. et al. Ontogeny of circadian rhythms and synchrony in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J. Neurosci. 38, 1326–1334 (2018).

Freeman, G. M. Jr & Herzog, E. D. Neuropeptides go the distance for circadian synchrony. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 13883–13884 (2011).

LeSauter, J. & Silver, R. Output signals of the SCN. Chronobiol. Int. 15, 535–550 (1998).

Maywood, E. S., Chesham, J. E., O’Brien, J. A. & Hastings, M. H. A diversity of paracrine signals sustains molecular circadian cycling in suprachiasmatic nucleus circuits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108, 14306–14311 (2011).

Silver, R., LeSauter, J., Tresco, P. A. & Lehman, M. N. A diffusible coupling signal from the transplanted suprachiasmatic nucleus controlling circadian locomotor rhythms. Nature 382, 810–813 (1996).

Kornhauser, J. M., Nelson, D. E., Mayo, K. E. & Takahashi, J. S. Photic and circadian regulation of c-fos gene expression in the hamster suprachiasmatic nucleus. Neuron 5, 127–134 (1990).

Campi, K. L. & Krubitzer, L. Comparative studies of diurnal and nocturnal rodents: differences in lifestyle result in alterations in cortical field size and number. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 4491–4512 (2010).

Cuesta, M., Clesse, D., Pevet, P. & Challet, E. From daily behavior to hormonal and neurotransmitters rhythms: comparison between diurnal and nocturnal rat species. Horm. Behav. 55, 338–347 (2009).

Hut, R. A., Mrosovsky, N. & Daan, S. Nonphotic entrainment in a diurnal mammal, the European ground squirrel (Spermophilus citellus). J. Biol. Rhythms 14, 409–419 (1999).

Qian, K. W. et al. Altered retinal dopamine levels in a melatonin-proficient mouse model of form-deprivation myopia. Neurosci. Bull. 38, 992–1006 (2022).

Bass, J. & Takahashi, J. S. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science 330, 1349–1354 (2010).

Lowrey, P. L. & Takahashi, J. S. Genetics of circadian rhythms in mammalian model organisms. Adv. Genet. 74, 175–230 (2011).

Chauhan, S. S. et al. Cloning, genomic organization, and chromosomal localization of human cathepsin L. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 1039–1045 (1993).

Marcheva, B. et al. Circadian clocks and metabolism. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25950-0_6 (2013).

Tahara, Y., Aoyama, S. & Shibata, S. The mammalian circadian clock and its entrainment by stress and exercise. J. Physiol. Sci. 67, 1–10 (2017).

Christensen, J., Li, C. & Mychasiuk, R. Choroid plexus function in neurological homeostasis and disorders: the awakening of the circadian clocks and orexins. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab.42, 1163–1175 (2022).

Quintela, T. et al. The role of circadian rhythm in choroid plexus functions. Prog. Neurobiol. 205, 102129 (2021).

Bitanihirwe, B. K. Y., Lizano, P. & Woo, T. W. Deconstructing the functional neuroanatomy of the choroid plexus: an ontogenetic perspective for studying neurodevelopmental and neuropsychiatric disorders. Mol. Psychiatry 27, 3573–3582 (2022).

Myung, J., Wu, D., Simonneaux, V. & Lane, T. J. Strong circadian rhythms in the choroid plexus: implications for sleep-independent brain metabolite clearance. J. Exp. Neurosci. 12, 1179069518783762 (2018).

Vizcarra, V. S., Fame, R. M. & Hablitz, L. M. Circadian mechanisms in brain fluid biology. Circ. Res. 134, 711–726 (2024).

Chang, J. T., Lehtinen, M. K. & Sive, H. Zebrafish cerebrospinal fluid mediates cell survival through a retinoid signaling pathway. Dev. Neurobiol. 76, 75–92 (2016).

Chau, K. F. et al. Progressive differentiation and instructive capacities of amniotic fluid and cerebrospinal fluid proteomes following neural tube closure. Dev. Cell 35, 789–802 (2015).

Fame, R. M. & Lehtinen, M. K. Emergence and developmental roles of the cerebrospinal fluid system. Dev. Cell 52, 261–275 (2020).

Jang, A. et al. Choroid plexus-CSF-targeted antioxidant therapy protects the brain from toxicity of cancer chemotherapy. Neuron 110, 3288–3301.e3288 (2022).

Lehtinen, M. K. et al. The cerebrospinal fluid provides a proliferative niche for neural progenitor cells. Neuron 69, 893–905 (2011).

Silva-Vargas, V., Maldonado-Soto, A. R., Mizrak, D., Codega, P. & Doetsch, F. Age-dependent niche signals from the choroid plexus regulate adult neural stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 19, 643–652 (2016).

Pardridge, W. M. CSF, blood-brain barrier, and brain drug delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 13, 963–975 (2016).

Fossan, G. et al. CSF-brain permeability in the immature sheep fetus: a CSF-brain barrier. Brain Res. 350, 113–124 (1985).

Whish, S. et al. The inner CSF-brain barrier: developmentally controlled access to the brain via intercellular junctions. Front. Neurosci. 9, 16 (2015).

Hladky, S. B. & Barrand, M. A. The glymphatic hypothesis: the theory and the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS 19, 9 (2022).

Weed, L. H. Studies on cerebro-spinal fluid. No. IV : The dual source of cerebro-spinal fluid. J. Med. Res. 31, 93–118 (1914).

Weed, L. H. Studies on cerebro-spinal fluid. No. III : The pathways of escape from the subarachnoid spaces with particular reference to the arachnoid villi. J. Med. Res. 31, 51–91 (1914).

Woollam, D. H. & Millen, J. W. The perivascular spaces of the mammalian central nervous system and their relation to the perineuronal and subarachnoid spaces. J. Anat. 89, 193–200 (1955).

Louveau, A. et al. Understanding the functions and relationships of the glymphatic system and meningeal lymphatics. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 3210–3219 (2017).

Bohr, T. et al. The glymphatic system: current understanding and modeling. iScience 25, 104987 (2022).

Holstein-Ronsbo, S. et al. Glymphatic influx and clearance are accelerated by neurovascular coupling. Nat. Neurosci. 26, 1042–1053 (2023).

Hablitz, L. M. et al. Increased glymphatic influx is correlated with high EEG delta power and low heart rate in mice under anesthesia. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav5447 (2019).

Dani, N. et al. A cellular and spatial map of the choroid plexus across brain ventricles and ages. Cell 184, 3056–3074.e3021 (2021).

Xu, H. et al. The choroid plexus synergizes with immune cells during neuroinflammation. Cell 187, 4946–4963.e4917 (2024).

Cui, J., Xu, H. & Lehtinen, M. K. Macrophages on the margin: choroid plexus immune responses. Trends Neurosci. 44, 864–875 (2021).

Carloni, S. et al. Identification of a choroid plexus vascular barrier closing during intestinal inflammation. Science 374, 439–448 (2021).

Keep, R. F. & Jones, H. C. A morphometric study on the development of the lateral ventricle choroid plexus, choroid plexus capillaries and ventricular ependyma in the rat. Brain Res. Dev. Brain Res. 56, 47–53 (1990).

Praetorius, J. & Damkier, H. H. Transport across the choroid plexus epithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 312, C673–C686 (2017).

Ghersi-Egea, J. F. et al. Molecular anatomy and functions of the choroidal blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier in health and disease. Acta Neuropathol.135, 337–361 (2018).

Strazielle, N. & Ghersi-Egea, J. F. Efflux transporters in blood-brain interfaces of the developing brain. Front. Neurosci. 9, 21 (2015).

Strazielle, N., Khuth, S. T. & Ghersi-Egea, J. F. Detoxification systems, passive and specific transport for drugs at the blood-CSF barrier in normal and pathological situations. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 56, 1717–1740 (2004).

Mazucanti, C. H. et al. Release of insulin produced by the choroid plexis is regulated by serotonergic signaling. JCI Insight 4, e131682 (2019).

Courtney, Y. et al. A choroid plexus apocrine secretion mechanism shapes CSF proteome and embryonic brain development. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.01.08.574486 (2024).

Mazucanti, C. H. et al. AAV5-mediated manipulation of insulin expression in choroid plexus has long-term metabolic and behavioral consequences. Cell Rep. 42, 112903 (2023).

Mazucanti, C. H. et al. Insulin is produced in choroid plexus and its release is regulated by serotonergic signaling. JCI Insight. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.131682 (2019).

Lindvall, M., Owman, C. & Winbladh, B. Sympathetic influence on transport functions in the choroid plexus of rabbit and rat. Brain Res. 223, 160–164 (1981).

Lindvall, M. & Owman, C. Autonomic nerves in the mammalian choroid plexus and their influence on the formation of cerebrospinal fluid. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab.1, 245–266 (1981).

Lindvall, M., Edvinsson, L. & Owman, C. Sympathetic nervous control of cerebrospinal fluid production from the choroid plexus. Science 201, 176–178 (1978).

Garcia-Garcia, A. & Mendez-Ferrer, S. The autonomic nervous system pulls the strings to coordinate circadian HSC functions. Front. Immunol. 11, 956 (2020).

Bouchaud, C. & Bosler, O. The circumventricular organs of the mammalian brain with special reference to monoaminergic innervation. Int. Rev. Cytol. 105, 283–327 (1986).

Nualart, F. et al. Hyperglycemia increases SCO-spondin and Wnt5a secretion into the cerebrospinal fluid to regulate ependymal cell beating and glucose sensing. PLoS Biol. 21, e3002308 (2023).

Rodriguez, E. M., Rodriguez, S. & Hein, S. The subcommissural organ. Microsc. Res. Tech. 41, 98–123 (1998).

Tan, D.-X., Manchester, L. C. & Reiter, R. J. CSF generation by pineal gland results in a robust melatonin circadian rhythm in the third ventricle as an unique light/dark signal. Med. Hypotheses 86, 3–9 (2016).

Garcia-Caceres, C. et al. Role of astrocytes, microglia, and tanycytes in brain control of systemic metabolism. Nat. Neurosci. 22, 7–14 (2019).

Mullier, A., Bouret, S. G., Prevot, V. & Dehouck, B. Differential distribution of tight junction proteins suggests a role for tanycytes in blood-hypothalamus barrier regulation in the adult mouse brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 518, 943–962 (2010).

Porniece Kumar, M. et al. Insulin signalling in tanycytes gates hypothalamic insulin uptake and regulation of AgRP neuron activity. Nat. Metab. 3, 1662–1679 (2021).

Poplack, D. G. et al. A primate model for study of methotrexate pharmacokinetics in the central nervous system. Cancer Res. 37, 1982–1985 (1977).

Cutler, R. W., Page, L., Galicich, J. & Watters, G. V. Formation and absorption of cerebrospinal fluid in man. Brain 91, 707–720 (1968).

Rubin, R. C., Henderson, E. S., Ommaya, A. K., Walker, M. D. & Rall, D. P. The production of cerebrospinal fluid in man and its modification by acetazolamide. J. Neurosurg. 25, 430–436 (1966).

Ahn, J. H. et al. Meningeal lymphatic vessels at the skull base drain cerebrospinal fluid. Nature 572, 62–66 (2019).

Ma, Q., Ineichen, B. V., Detmar, M. & Proulx, S. T. Outflow of cerebrospinal fluid is predominantly through lymphatic vessels and is reduced in aged mice. Nat. Commun. 8, 1434 (2017).

Koh, L. et al. Development of cerebrospinal fluid absorption sites in the pig and rat: connections between the subarachnoid space and lymphatic vessels in the olfactory turbinates. Anat. Embryol. 211, 335–344 (2006).

Nagra, G., Koh, L., Zakharov, A., Armstrong, D. & Johnston, M. Quantification of cerebrospinal fluid transport across the cribriform plate into lymphatics in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. 291, R1383–R1389 (2006).

Papaiconomou, C., Bozanovic-Sosic, R., Zakharov, A. & Johnston, M. Does neonatal cerebrospinal fluid absorption occur via arachnoid projections or extracranial lymphatics? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr.Comp. Physiol. 283, R869–R876 (2002).

Choi, D. et al. Piezo1 regulates meningeal lymphatic vessel drainage and alleviates excessive CSF accumulation. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 913–926 (2024).

Matrongolo, M. J. et al. Piezo1 agonist restores meningeal lymphatic vessels, drainage, and brain-CSF perfusion in craniosynostosis and aged mice. J. Clin. Invest. 134, e171468 (2023).

Miyazaki, M. et al. Physical exercise alters egress pathways for intrinsic CSF outflow: an investigation performed with spin-labeling MR imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 23, 171–183 (2024).

Zappaterra, M. D. et al. A comparative proteomic analysis of human and rat embryonic cerebrospinal fluid. J. Proteome Res. 6, 3537–3548 (2007).

Fame, R. M., Xu, H., Pragana, A. & Lehtinen, M. Age-appropriate potassium clearance from perinatal cerebrospinal fluid depends on choroid plexus NKCC1. Fluids Barriers CNS 20, 45 (2023).

Xu, H. et al. Choroid plexus NKCC1 mediates cerebrospinal fluid clearance during mouse early postnatal development. Nat. Commun. 12, 447 (2021).

Saunders, N. R., Dziegielewska, K. M., Møllgård, K. & Habgood, M. D. Physiology and molecular biology of barrier mechanisms in the fetal and neonatal brain. J. Physiol. 596, 5723–5756 (2018).

Gregg, C. & Weiss, S. CNTF/LIF/gp130 receptor complex signaling maintains a VZ precursor differentiation gradient in the developing ventral forebrain. Development 132, 565–578 (2005).

Lamus, F. et al. FGF2/EGF contributes to brain neuroepithelial precursor proliferation and neurogenesis in rat embryos: the involvement of embryonic cerebrospinal fluid. Dev. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1002/dvdy.135 (2019).

Martin, C. et al. FGF2 plays a key role in embryonic cerebrospinal fluid trophic properties over chick embryo neuroepithelial stem cells. Dev. Biol. 297, 402–416 (2006).

Kaiser, K. et al. MEIS-WNT5A axis regulates development of fourth ventricle choroid plexus. Development 148, dev192054 (2021).

Langford, M. B. et al. WNT5a regulates epithelial morphogenesis in the developing choroid plexus. Cereb. Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhz330 (2020).

Conn, P. J., Sanders-Bush, E., Hoffman, B. J. & Hartig, P. R. A unique serotonin receptor in choroid plexus is linked to phosphatidylinositol turnover. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 83, 4086–4088 (1986).

Esterle, T. M. & Sanders-Bush, E. Serotonin agonists increase transferrin levels via activation of 5-HT1C receptors in choroid plexus epithelium. J. Neurosci. 12, 4775–4782 (1992).

Tsutsumi, M. & Sanders-Bush, E. 5-HT-induced transferrin production by choroid plexus epithelial cells in culture: role of 5-HT1c receptor. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 254, 253–257 (1990).

Tietje, A., Maron, K. N., Wei, Y. & Feliciano, D. M. Cerebrospinal fluid extracellular vesicles undergo age dependent declines and contain known and novel non-coding RNAs. PLoS ONE 9, e113116 (2014).

Feliciano, D. M., Zhang, S., Nasrallah, C. M., Lisgo, S. N. & Bordey, A. Embryonic cerebrospinal fluid nanovesicles carry evolutionarily conserved molecules and promote neural stem cell amplification. PLoS ONE 9, e88810 (2014).

Marzesco, A. M. et al. Release of extracellular membrane particles carrying the stem cell marker prominin-1 (CD133) from neural progenitors and other epithelial cells. J. Cell Sci. 118, 2849–2858 (2005).

Coulter, M. E. et al. The ESCRT-III protein CHMP1A mediates secretion of Sonic Hedgehog on a distinctive subtype of extracellular vesicles. Cell Rep. 24, 973–986.e978 (2018).

Balusu, S. et al. Identification of a novel mechanism of blood-brain communication during peripheral inflammation via choroid plexus-derived extracellular vesicles. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 1162–1183 (2016).

Stremersch, S. et al. Comparing exosome-like vesicles with liposomes for the functional cellular delivery of small RNAs. J. Control. Release 232, 51–61 (2016).

Fame, R. M., Ali, I., Lehtinen, M. K., Kanarek, N. & Petrova, B. Optimized mass spectrometry detection of thyroid hormones and polar metabolites in rodent cerebrospinal fluid. Metabolites. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo14020079 (2024).

Fame, R. M., Shannon, M. L., Chau, K. F., Head, J. P. & Lehtinen, M. K. A concerted metabolic shift in early forebrain alters the CSF proteome and depends on MYC downregulation for mitochondrial maturation. Development 146, dev182857 (2019).

Chau, K. F. et al. Downregulation of ribosome biogenesis during early forebrain development. eLife 7, e36998 (2018).

Antila, S. et al. Development and plasticity of meningeal lymphatic vessels. J. Exp. Med. 214, 3645–3667 (2017).

Saunders, N. R., Dziegielewska, K. M., Fame, R. M., Lehtinen, M. K. & Liddelow, S. A. The choroid plexus: a missing link in our understanding of brain development and function. Physiol. Rev. 103, 919–956 (2023).

Liddelow, S. A. et al. Mechanisms that determine the internal environment of the developing brain: a transcriptomic, functional and ultrastructural approach. PLoS ONE 8, e65629 (2013).

Liddelow, S. A. et al. Molecular characterisation of transport mechanisms at the developing mouse blood-CSF interface: a transcriptome approach. PLoS ONE 7, e33554 (2012).

O’Brown, N. M., Pfau, S. J. & Gu, C. Bridging barriers: a comparative look at the blood-brain barrier across organisms. Genes Dev. 32, 466–478 (2018).

Spassky, N. et al. Adult ependymal cells are postmitotic and are derived from radial glial cells during embryogenesis. J. Neurosci. 25, 10–18 (2005).

Derk, J. et al. Formation and function of the meningeal arachnoid barrier around the developing mouse brain. Dev. Cell 58, 635–644.e634 (2023).

Gomez, D. G. et al. Development of arachnoid villi and granulations in man. Acta Anat.111, 247–258 (1982).

Lunde, L. K. et al. Postnatal development of the molecular complex underlying astrocyte polarization. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 2087–2101 (2015).

Munk, A. S. et al. PDGF-B is required for development of the glymphatic system. Cell Rep. 26, 2955–2969.e2953 (2019).

Chen, C. P., Chen, R. L. & Preston, J. E. The influence of ageing in the cerebrospinal fluid concentrations of proteins that are derived from the choroid plexus, brain, and plasma. Exp. Gerontol. 47, 323–328 (2012).

Chen, C. P., Chen, R. L. & Preston, J. E. The influence of cerebrospinal fluid turnover on age-related changes in cerebrospinal fluid protein concentrations. Neurosci. Lett. 476, 138–141 (2010).

Sun, Z., Li, C., Zhang, J., Wisniewski, T. & Ge, Y. Choroid plexus aging: structural and vascular insights from the HCP-aging dataset. Fluids Barriers CNS 21, 98 (2024).

Lananna, B. V. & Musiek, E. S. The wrinkling of time: aging, inflammation, oxidative stress, and the circadian clock in neurodegeneration. Neurobiol. Dis. 139, 104832 (2020).

Garrick, N. A. et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor: a marked circadian rhythm in primate cerebrospinal fluid peaks in the evening and is inversely related to the cortisol circadian rhythm. Endocrinology 121, 1329–1334 (1987).

Hedlund, L., Lischko, M. M., Rollag, M. D. & Niswender, G. D. Melatonin: daily cycle in plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of calves. Science 195, 686–687 (1977).

Reppert, S. M., Perlow, M. J., Tamarkin, L. & Klein, D. C. A diurnal melatonin rhythm in primate cerebrospinal fluid. Endocrinology 104, 295–301 (1979).

Deboer, T. et al. Convergence of circadian and sleep regulatory mechanisms on hypocretin-1. Neuroscience 129, 727–732 (2004).

Zhang, S. et al. Lesions of the suprachiasmatic nucleus eliminate the daily rhythm of hypocretin-1 release. Sleep 27, 619–627 (2004).

Castillo-Ruiz, A., Gall, A. J., Smale, L. & Nunez, A. A. Day-night differences in neural activation in histaminergic and serotonergic areas with putative projections to the cerebrospinal fluid in a diurnal brain. Neuroscience 250, 352–363 (2013).

Fame, R. M. et al. Defining diurnal fluctuations in mouse choroid plexus and CSF at high molecular, spatial, and temporal resolution. Nat. Commun. 14, 3720 (2023).

Hochbaum, D. R. et al. Thyroid hormone remodels cortex to coordinate body-wide metabolism and exploration. Cell 187, 5679–5697.e23 (2024).

Edelbo, B. L., Andreassen, S. N., Steffensen, A. B. & MacAulay, N. Day-night fluctuations in choroid plexus transcriptomics and cerebrospinal fluid metabolomics. PNAS Nexus 2, pgad262 (2023).

Ding, F. et al. Changes in the composition of brain interstitial ions control the sleep-wake cycle. Science 352, 550–555 (2016).

Forsberg, M. et al. Ion concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid in wakefulness, sleep and sleep deprivation in healthy humans. J. Sleep. Res.31, e13522 (2022).

Amzica, F. Physiology of sleep and wakefulness as it relates to the physiology of epilepsy. J. Clin. Neurophysiol. 19, 488–503 (2002).

Semba, R. D. et al. Klotho in the cerebrospinal fluid of adults with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 558, 37–40 (2014).

Steffensen, A. B. et al. Nocturnal increase in cerebrospinal fluid secretion as a circadian regulator of intracranial pressure. Fluids Barriers CNS 20, 49 (2023).

Eide, P. K., Vinje, V., Pripp, A. H., Mardal, K. A. & Ringstad, G. Sleep deprivation impairs molecular clearance from the human brain. Brain 144, 863–874 (2021).

Miyakoshi, L. M. et al. The state of brain activity modulates cerebrospinal fluid transport. Prog. Neurobiol. 229, 102512 (2023).

Westgate, C. S. J., Israelsen, I. M. E., Kamp-Jensen, C., Jensen, R. H. & Eftekhari, S. Glucocorticoids modify intracranial pressure in freely moving rats. Fluids Barriers CNS 20, 35 (2023).

Quay, W. B. Twenty-four-hour rhythmicity in carbonic anhydrase activities of choroid plexuses and pineal gland. Anat. Rec. 174, 279–287 (1972).

Catala, M. Carbonic anhydrase activity during development of the choroid plexus in the human fetus. Child’s Nerv. Syst.13, 364–368 (1997).

Yamaguchi, T., Hamada, T., Matsuzaki, T. & Iijima, N. Characterization of the circadian oscillator in the choroid plexus of rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 524, 497–501 (2020).

Rosbash, M. Circadian rhythms and the transcriptional feedback loop (Nobel lecture). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 8650–8666 (2021).

Gekakis, N. et al. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science 280, 1564–1569 (1998).

Vitaterna, M. H. et al. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science 264, 719–725 (1994).

Myung, J. et al. The choroid plexus is an important circadian clock component. Nat. Commun. 9, 1062 (2018).

Quintela, T. et al. The choroid plexus harbors a circadian oscillator modulated by estrogens. Chronobiol. Int. 35, 270–279 (2018).

Mure, L. S. et al. Diurnal transcriptome atlas of a primate across major neural and peripheral tissues. Science 359, eaao0318 (2018).

Szczepkowska, A., Harazin, A., Barna, L., Deli, M. A. & Skipor, J. Identification of reference genes for circadian studies on brain microvessels and choroid plexus samples isolated from rats. Biomolecules 11, 1227 (2021).

Rodriguez, E. M. & Heller, H. Antidiuretic activity and ultrastructure of the toad choroid plexus. J. Endocrinol. 46, 83–91 (1970).

Bratincsak, A. et al. Spatial and temporal activation of brain regions in hibernation: c-fos expression during the hibernation bout in thirteen-lined ground squirrel. J. Comp. Neurol. 505, 443–458 (2007).

Quintela, T. et al. Analysis of the effects of sex hormone background on the rat choroid plexus transcriptome by cDNA microarrays. PLoS ONE 8, e60199 (2013).

Quintela, T., Sousa, C., Patriarca, F. M., Goncalves, I. & Santos, C. R. Gender associated circadian oscillations of the clock genes in rat choroid plexus. Brain Struct. Funct. 220, 1251–1262 (2015).

Sladek, M. et al. The circadian clock in the choroid plexus drives rhythms in multiple cellular processes under the control of the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Fluids Barriers CNS 21, 46 (2024).

Liska, K., Sladek, M., Cecmanova, V. & Sumova, A. Glucocorticoids reset circadian clock in choroid plexus via period genes. J. Endocrinol. 248, 155–166 (2021).

Quintela, T. et al. Sex-related differences in rat choroid plexus and cerebrospinal fluid: a cDNA microarray and proteomic analysis. J. Neuroendocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jne.12340 (2016).

Yoo, S. H. et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 5339–5346 (2004).

Quintela, T. et al. Choroid plexus is an additional source of melatonin in the brain. J. Pineal Res. 65, e12528 (2018).

Furtado, A. et al. The rhythmicity of clock genes is disrupted in the choroid plexus of the APP/PS1 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.77, 795–806 (2020).

Drapsin, M. et al. Circadian clock in choroid plexus is resistant to immune challenge but dampens in response to chronodisruption. Brain Behav. Immun. 117, 255–269 (2024).

Furtado, A. et al. Circadian ABCG2 expression influences the brain uptake of donepezil across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 25, 5014 (2024).

Furtado, A. et al. The daily expression of ABCC4 at the BCSFB affects the transport of its substrate methotrexate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 2443 (2022).

Taranov, A. et al. The choroid plexus maintains adult brain ventricles and subventricular zone neuroblast pool, which facilitates poststroke neurogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2400213121 (2024).

Jang, A. & Lehtinen, M. K. Experimental approaches for manipulating choroid plexus epithelial cells. Fluids Barriers CNS 19, 36 (2022).

Mineiro, R. et al. The role of biological rhythms in new drug formulations to cross the brain barriers. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, 12541 (2023).

Saunders, N. R., Habgood, M. D., Mollgard, K. & Dziegielewska, K. M. The biological significance of brain barrier mechanisms: help or hindrance in drug delivery to the central nervous system? F1000Research 5, F1000 (2016).

Fattal, O., Link, J., Quinn, K., Cohen, B. H. & Franco, K. Psychiatric comorbidity in 36 adults with mitochondrial cytopathies. CNS Spectr. 12, 429–438 (2007).

Da Silva, T. et al. Mitochondrial function in individuals at clinical high risk for psychosis. Sci. Rep. 8, 6216 (2018).

Sonntag, K. C. et al. Late-onset Alzheimer’s disease is associated with inherent changes in bioenergetics profiles. Sci. Rep. 7, 14038 (2017).

Furtado, A. et al. Circadian rhythmicity of amyloid-beta-related molecules is disrupted in the choroid plexus of a female Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Neurosci. Res. 101, 524–540 (2023).

Duarte, A. C. et al. Age, sex hormones, and circadian rhythm regulate the expression of amyloid-beta scavengers at the choroid plexus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 6813 (2020).

Blattner, M. S. et al. Increased cerebrospinal fluid amyloid-beta during sleep deprivation in healthy middle-aged adults is not due to stress or circadian disruption. J. Alzheimer’s Dis.75, 471–482 (2020).

Miao, A. et al. Brain clearance is reduced during sleep and anesthesia. Nat. Neurosci. 27, 1046–1050 (2024).

Kroesbergen, E. et al. Glymphatic clearance is enhanced during sleep. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.24.609514 (2024).

Yamaguchi, T., Hamada, T. & Iijima, N. Differences in recovery processes of circadian oscillators in various tissues after sevoflurane treatment in vivo. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 30, 101258 (2022).

Liska, K. et al. Lithium affects the circadian clock in the choroid plexus—a new role for an old mechanism. Biomed. Pharmacother. 159, 114292 (2023).

Shipley, F. B. et al. Tracking calcium dynamics and immune surveillance at the choroid plexus blood-cerebrospinal fluid interface. Neuron 108, 623–639.e610 (2020).

Biffo, S., Ruggero, D. & Santoro, M. M. The crosstalk between metabolism and translation. Cell Metab. 36, 1945–1962 (2024).

Kim, T., Kim, S., Kang, J., Kwon, M. & Lee, S. H. The common effects of sleep deprivation on human long-term memory and cognitive control processes. Front. Neurosci. 16, 883848 (2022).

Wu, D. et al. The blood-brain barrier: structure, regulation, and drug delivery. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 217 (2023).

Barker, S. J. et al. Targeting the transferrin receptor to transport antisense oligonucleotides across the mammalian blood-brain barrier. Sci. Transl. Med. 16, eadi2245 (2024).

Strazielle, N. & Ghersi-Egea, J. F. Potential pathways for CNS drug delivery across the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier. Curr. Pharm. Des. 22, 5463–5476 (2016).

Hudry, E. et al. Gene transfer of human Apoe isoforms results in differential modulation of amyloid deposition and neurotoxicity in mouse brain. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 212ra161 (2013).

Hudry, E. & Vandenberghe, L. H. Therapeutic AAV gene transfer to the nervous system: a clinical reality. Neuron 101, 839–862 (2019).

Haddad, M. R., Donsante, A., Zerfas, P. & Kaler, S. G. Fetal brain-directed AAV gene therapy results in rapid, robust, and persistent transduction of mouse choroid plexus epithelia. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2, e101 (2013).

Kaler, S. G. Menkes disease. Adv. Pediatr. 41, 263–304 (1994).

Acknowledgements

I apologize to investigators whose work could not be referenced owing to space limitations. I thank the members of the Fame laboratory and Prof. Nanna MacAulay for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the Shurl and Kay Curci Foundation (R.M.F.), the Brain Research Foundation Seed Grant (R.M.F.), and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) R01 MH136258 (R.M.F.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.M.F.: Funding Acquisition; Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Figure preparation; Supervision; Writing—review & editing; Writing—final draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fame, R.M. Harnessing the circadian nature of the choroid plexus and cerebrospinal fluid. npj Biol Timing Sleep 2, 19 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00033-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44323-025-00033-5