Abstract

Apolipoproteins are structural components of lipoproteins involved in assembly, enzyme regulation, structural integrity, and receptor binding. Apoprotein(a) forms lipoprotein(a), apolipoprotein A-I drives reverse cholesterol transport, apolipoprotein B reflects atherogenic particle number, and apolipoprotein C-III regulates triglycerides. This review highlights the clinical significance of these apolipoproteins in coronary plaque characteristics detected by imaging modality. Additionally, we summarize the current clinical status of therapeutic agents targeting these apolipoproteins and its future potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The impacts of apolipoproteins in vivo may seem more esoteric compared to lipoproteins due to these multifaceted functions; however, a basic appreciation of their functions is essential for not only a deeper understanding of lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, but also considering the risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide1. There have been many reports that lipoproteins represented by low-density lipoproteins cholesterol (LDL-C) strongly relate to development of coronary artery plaques that affects ASCVD occurrence2,3; however, apolipoproteins also influence atherosclerotic profiles. In this review, we discuss the clinical significance of apolipoprotein(a) [Apo(a)], apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I), apolipoprotein B (ApoB), and apolipoprotein C-III (ApoC-III) among serum apolipoproteins that would be particularly relevant to atherosclerotic coronary plaques. Furthermore, we summarize the insights into novel agents that target specific apolipoproteins to reduce the risk of ASCVD and attenuate the atherosclerotic coronary plaques.

Methods

To be included in this review, studies needed to meet the following criteria; (1) explore apolipoproteins influencing atherosclerotic coronary plaques as a primary aim; (2) qualitative methodology (e.g., data-collection, method of analysis); (3) usage of imaging modality (intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), optical coherence tomography (OCT), and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA)) or histopathological examination; (4) focus on adults (i.e., ≥18 years); and (5) published in English. We searched the electronic database of PubMed, SCOPUS, EBSCO, and Cochrane Library from January 2000 until November 2025 for studies that evaluated the association between apolipoproteins and atherosclerotic coronary plaques. The terms used for searching were “lipoprotein(a)”, “apolipoprotein(a)”, “apolipoprotein A-I”, “apolipoprotein B”, “apolipoprotein C-III”, “coronary plaques”, “intravascular ultrasound”, “optical coherence tomography”, and “coronary computed tomography angiography”, and we searched for these combinations. Randomized controlled trials, observational studies, including case control studies, prospective cohort study, retrospective observational study, reviews, and meta-analysis were including if reference was made to apolipoproteins and atherosclerotic coronary plaques. Studies were selected by co-authors by screening the title and abstract. As results, 986 studies were found. Of these, only 34 met the inclusion criteria, and we finally reviewed the full text for the selected studies as shown in Fig. 1. The association of each apolipoprotein with plaques is summarized in Table 1, and section of “Imaging correlates” provided details of major and large clinical studies on the association of each apolipoprotein with atherosclerotic coronary plaques. The unknown confounding factors may have influenced the outcomes despite statical adjustments in each study, and the studies with small sample size may have limited the statistical power.

PRISMA-style flow diagram illustrating the systematic literature search and selection process. The initial database search yielded 1195 records. After duplicate removal, 946 records were screened at the title and abstract level. Of these, 876 records were excluded. 70 full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, 34 studies finally included in qualitative synthesis.

Pathophysiological roles and genetic insights

Apolipoproteins are essential components of plasma lipoproteins, which have complex macromolecular structures composed of an envelope of phospholipids and free cholesterol, and a core of cholesteryl ester and triglyceride (TG). The term “apolipoprotein” is made up of two words: “apo,” a Greek word that means “away from,” and “lipoprotein,” which refers to the lipid-protein complex4. Clinically important apolipoproteins such as apolipoprotein ApoA-I, apolipoprotein A-II, apolipoprotein B-100 (ApoB-100), apolipoprotein B-48 (ApoB-48), apolipoprotein C-II (ApoC-II), ApoC-III, apolipoprotein E (ApoE), and Apo(a) are associated with several disease conditions, including dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease and neurodegenerative disorders. Figure 2 shows the illustrative diagram of lipid transport and metabolic pathway. Among them, ApoB is the only non-exchangeable apolipoprotein; it’s β-sheet secondary structure enables stable binding with lipoprotein particles5. The other apolipoproteins are exchangeable, and they can dissociate from one lipoprotein and reassociate with another lipoprotein6. Apolipoproteins have four major roles: (1) assembly and secretion of the lipoprotein (ApoA-I, ApoB-100, and ApoB-48)7,8; (2) coactivators or inhibitors of enzymes (ApoA-I, ApoC-II, and ApoC-III)9,10; (3) structural integrity of lipoprotein (ApoB, ApoE, and ApoA-I)11; and (4) binding or docking to specific receptors and proteins for cellular uptake of the entire particle or selective uptake of the lipid component (ApoA-I, ApoB-100, and ApoE)11. Among these, we will highlight and review apolipoproteins, which are thought to be closely related to atherosclerotic coronary plaques. The structure, function, and pathophysiological role in ASCVD of each apolipoprotein are summarized in Table 2.

In the small intestine, chylomicrons are assembled to transport dietary fats from the enterocytes into the lymphatic system, which subsequently then delivers them to the bloodstream. Dietary lipids are digested, re-esterified, and packaged together with apolipoproteins such as ApoB-48, ApoC-II, ApoC-III, and ApoE into chylomicrons. These particles distribute fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins to peripheral tissues before their remnants are cleared by the liver. The endogenous lipoprotein pathway begins in the liver with the secretion of VLDL. TG carried in VLDL are hydrolyzed in muscle and adipose tissue by LPL, releasing free fatty acids and generating IDL. IDL particles are further metabolized to by LPL and HL to form LDL, which delivers cholesterol to peripheral tissues and is cleared primarily by LDL receptors in the liver. Lp(a) is structurally similar to LDL, consisting of ApoB-100 covalently bound to Apo(a), but functions independently and is recognized as a distinct atherogenic lipoprotein. Reverse cholesterol transport is the pathway by which excess peripheral cholesterol is returned to the liver. ApoA-I, secreted by the liver and intestine, acquires free cholesterol from peripheral cells, including macrophages and endothelial cells, via ABCA1, forming the nascent HDL. This nascent HDL is converted into mature HDL by LCAT, which esterifies free cholesterol into CE that are sequestered into the particle core. HDL delivers cholesterol to the liver either directly, through interaction with hepatic SR-B1, or indirectly, via CETP-mediated exchange of TG with other atherogenic lipoproteins (chylomicron, VLDL, IDL, and LDL). ABCA1 ATP-binding cassette transporter A1, ApoA-I apolipoprotein A-I, Apo(a) apolipoprotein (a), ApoB-48 apolipoprotein B-48, ApoB-100 apolipoprotein B-100, ApoC-II apolipoprotein C-II, ApoC-III apolipoprotein C-III, ApoE apolipoprotein E, CE cholesterol ester, CETP cholesteryl ester transfer protein, HDL high-density lipoprotein, HL hepatic lipase, IDL intermediate-density lipoprotein, LCAT lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase, LDL low-density cholesterol, Lp(a) lipoprotein (a), LPL lipoprotein lipase, SR-B1 scavenger receptor B1, TG triglyceride, VLDL very low-density lipoprotein.

Circulating lipoprotein (a) [Lp(a)] levels are primarily determined by the LPA gene locus12. Apo(a) is synthesized almost exclusively in the liver, but the site of assembly of Lp(a) has not been confirmed, and may be within the hepatocyte, the space of Disse, or the plasma compartment13. Lp(a) assembly begins with Apo(a) docking to low-density lipoprotein (LDL), followed by formation of a covalent disulfide bond between Kringle IV-type 9 of Apo(a) and ApoB of LDL, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3. The LDL component is thought to be derived from a newly synthesized ApoB-10014. LPA contains multiple Kringle domains, including a hypervariable Kringle IV-type 2 region of ~5500 bp, which occurs in tandem from fewer than six copies to at least 40 times, and higher KIV-2 copy number generally associates with decreased Lp(a) protein abundance15,16. Lp(a) levels are determined almost exclusively by variants in the LPA gene, without significant dietary or environmental influences; thus, Lp(a) measurement is recommended at least once in a lifetime in several guidelines17,18. Lp(a) levels in humans are primarily measured by immunoassays using polyclonal antibodies against Apo(a). There are two common approaches for reporting results. The first is based on the assignment of target values to the assay calibrators in terms of total Lp(a) mass (Apo(a), ApoB and the lipid components). The values are expressed in mg/dL and there is no traceability of the various calibrators to any established reference material. The second approach, used in several commercial methods, is to assign the target values to assay calibrators traceable to the World Health Organization and the International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine secondary reference materials. The values are expressed in nmol/L of Apo(a), reflecting the number of circulating particles rather than the variable mass of Apo(a) or lipid component19. The assay calibration in mg/dL of total Lp(a) mass should be discontinued considering that only Apo(a) is measured by the antibodies and that the mass of Apo(a) is highly variable; thus, it is recommended that standardized Lp(a) assays report values in Apo(a) particle number, as nmol/L.

Lp(a) is composed of two parts; LDL-like particles with ApoB-100 and Apo(a) covalently bound by disulfide bounds. Apo(a) contains 10 types of KIV subtypes: one copy of KIV1 and KIV3-10, and variable KIV2 repetition. Apo(a) apolipoprotein (a), ApoB-100 apolipoprotein B-100, KIV kringle IV, LDL low-density cholesterol, Lp(a) lipoprotein (a).

ApoA-I encoded by APOA1 is a protein composed of 243 amino acids with a molecular weight of approximately 28,400 Da, and is synthesized and secreted by the small intestine and liver20. ApoA-I is a major structural and functional protein component of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) as shown in Fig. 4, constituting approximately 70% of its composition21. Through this role, ApoA-I is central to lipid metabolism, mediating cholesterol transport, and inflammatory, immunological, and vasodilatory pathways22. In particular, ApoA-I is crucial for HDL maturation, and two sequential lipidation steps are required, shown in Fig. 220. ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1) loads ApoA-I with phospholipids and cholesterol to form nascent HDL. Nascent HDL incorporating ApoA-I is secreted into the blood, and then matured by lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT). The most important function of ApoA-I is the activation of LCAT, an enzyme that converts free cholesterol on lipoproteins to cholesterol ester (CE). This reaction is essential for the maturation of nascent HDL and for the esterification of cholesterol derived from peripheral tissues. The rapid CE accumulation and phospholipid transfer convert the lipid-poor discoidal HDL into CE-rich spherical HDL particles; however, defects in either ABCA1-mediated lipidation or LCAT activity result in reduced HDL ApoA-I levels23,24. Mature HDL particles mediate cholesterol efflux from foam cells after interacting with ATP-binding cassette transporter G1/4 and scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1). Subsequently, cholesterol-laden mature HDL delivers CE to the liver via hepatic SR-B125,26. Therefore, ApoA-I, the main carrier protein of HDL, is critical to reverse the cholesterol transport process which is the pathway by which excess peripheral cholesterol is returned to the liver, and plays a crucial role in the cellular cholesterol efflux capacity (CEC) mechanism.

ApoB is an essential component of very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL), and its metabolites, IDL and LDL as shown in Fig. 5, as well as chylomicron and their remnants27. The ApoB particle serves as a structural scaffold, crucial for lipoprotein stability28. There are two circulating forms of ApoB. ApoB-100 is mainly synthesized and expressed in the liver and is an integral component of VLDL, IDL and LDL29, whereas ApoB-48 together with ApoC-II, ApoC-III, and ApoE is primarily synthesized and expressed within the small intestine and is present in chylomicron and its remnant, shown in Fig. 230. Both ApoB-100 and ApoB-48 are encoded by APOB. ApoB-100 consists of 4536 amino acids (molecular weight ~540 kDa), while ApoB-48 consists of 2152 amino acids (molecular weight ~264 kDa)31. ApoB-48, found on chylomicron and their remnants, is cleared primarily by the heparin sulfate proteoglycan pathway because they lack an LDL-receptor (LDLR) biding domain32. Elevated ApoB-48 levels may result from obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia, genetic disorders, or high-fat diets. ApoB-48 is unique to intestinal chylomicron-derived remnant cholesterol particles and contribute to non-fasting remnant cholesterol concentration33. While chylomicron itself is too large to penetrate the arterial wall, its remnant may do so and is thought to contribute to lipid accumulation in atherosclerotic plaque34. In addition, fasting ApoB-48 is associated with the incidence of coronary artery disease, and elevated ApoB-48 levels, together with risk factors for metabolic syndrome, exacerbate the risk of coronary artery disease35; however, of the two forms, ApoB-100 is more clinically relevant in determining the level of circulating atherogenic lipoproteins36. ApoB measurement can be considered a powerful tool for assessment of atherogenic lipid status, such as VLDL cholesterol, IDL cholesterol, LDL-C, and Lp(a) particle because each particle contains exactly one molecule of ApoB-100. Nascent ApoB-100 particles are lipidated in the endoplasmic reticulum by microsomal TG transfer protein to form TG-rich VLDL particles. After they are secreted into the circulation, lipoprotein lipase (LPL) metabolizes VLDL to produce IDL, which is further metabolized by LPL and hepatic lipase to form cholesteryl ester-rich LDL. LDL carries the majority of the circulating cholesterol, and can be oxidatively modified and taken up by macrophages which leads to excess accumulation and the formation of foam cells37. As such, more than 90% of circulating ApoB resides in LDL particles38.

One molecule of ApoB-100 encircles VLDL, LDL, and Lp(a) particles; whereas, one molecule of ApoB-48 encircles a chylomicron or chylomicron remnant particles. Apo(a) apolipoprotein (a), ApoB-48 apolipoprotein B-48, ApoB-100 apolipoprotein B-100, CE cholesterol ester, LDL low-density cholesterol, Lp(a) lipoprotein (a), TG triglyceride, VLDL very low-density lipoprotein.

LPL, synthesized in adipocytes, skeletal myocytes, and cardiomyocytes, is an essential enzyme for the lipolytic processing of TG in chylomicron and VLDL. ApoC-II is a critical LPL cofactor that promotes TG hydrolysis by facilitating substrate entry into the enzyme’s active site, whereas ApoC-III and angioproietin-related protein 3 (ANGPTL3) function as an inhibitor39. ApoC-III is primarily synthesized by the liver and to a lesser extent by enterocytes, where the human APOC3 gene is expressed. Mature ApoC-III protein consists of 79 amino acids, with a molecular mass of 8.8 kDa40. Recent research has demonstrated that ApoC-III impacts TG-rich lipoproteins (TRL) metabolism, inflammation, atherosclerosis progression, glucose metabolism, and cardiovascular diseases41. ApoC-III inhibits hepatic uptake of TRL remnants uptake by displacing ApoE from the lipoprotein surface. This prevents ApoE from interacting with the LDLR and LDL-related protein 1 on hepatocytes. Consequently, ApoC-III influences atherosclerosis by promoting LDL retention and aggregation in the subendothelial space, as well as triggering inflammatory cascades and smooth muscle cell proliferation in the arterial wall39.

Imaging correlates

Our search yielded multiple studies with divergent conclusions as shown in Table 1. We finally selected 17 clinical studies on the association between Lp(a) levels and atherosclerotic coronary plaques. LDL and remnant enter the intima and become trapped partly due to pressure gradient and their binding to glycosaminoglycans. Both lipoproteins can be internalized by macrophages to produce foam cells, which are a principal component of early atherosclerotic lesions. Lp(a) similarly enters to the intima; however, it remains unclear whether macrophages internalized Lp(a) to form foam cells. High plasma levels of LDL, remnants and possibly Lp(a) promote accumulation of inflammatory cells, including foam cells, enhancing atherosclerotic plaque formation. As a major study on the Lp(a) and coronary plaques detected by IVUS, post hoc analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials was divided into the two groups; 683 subjects (17.3%) had Lp(a) ≥ 60 mg/dL and 3260 subjects (82.7%) had Lp(a) < 60 mg/dL, and showed that percentage atheroma volume (PAV) measured by IVUS was significantly higher in the high Lp(a) group in unadjusted (38.2% [32.8, 43.6] vs. 37.1% [31.4, 43.1], p = 0.01) and risk-adjusted analyses (38.7% ± 0.5 vs. 37.5% ± 0.5, p < 0.001). There was a significant association of increasing risk-adjusted PAV across quintiles of Lp(a) (Lp(a) quintiles 1–5; 37.3 ± 0.5%, 37.2 ± 0.5%, 37.3 ± 0.5%, 38.0 ± 0.5%, 38.5 ± 0.5%, p = 0.002)42. In addition, some clinical studies have reported that elevated baseline Lp(a) levels in patients with ASCVD are associated with accelerated plaque progression assessed by CCTA43,44,45,46,47,48, high-risk plaque features detected by OCT49,50,51, and plaque burden and necrotic core progression on IVUS42,52,53. Additionally, Shishikura, et al. has reported that LDL-C levels and Lp(a) levels are independent strong risk factors for large lipid-rich plaques detected by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS)-IVUS. Patients with both LDL-C < 70 mg/dL and Lp(a) < 50 mg/dL have an approximately 70% lower risk of large lipid-rich plaques compared with patients with both LDL-C ≥ 70 mg/dL and Lp(a) ≥50 mg/dL, at the de-novo target lesion level54. However, the SATURN has shown that Lp(a) levels (predominantly below the 50 mg/dL threshold) do not associate with coronary atheroma progression55. It may occur that the 60% of patients in SATURN were already taking maximally intensive statin therapy, so there is a possibility that regression of focal large vulnerable plaque may have been potentially achieved. In addition, this may be due to the fact that the plaque burden reported in SATURN was tended to be smaller compared with other studies42,52,53. The PROSPECT II substudy has recently revealed that LDL-C were associated with pancoronary plaque volume and lipid core; conversely, Lp(a) was associated with the presence of focal large plaque burden and vulnerable plaque56. In summary, the difference in their effects on plaque localization demonstrates that Lp(a) may pose a residual risk not only at the patient level but also at the vessel level in an era when LDL-C lowering therapy is the mainstay of ASCVD treatment. Thus, therapeutic intervention targeting Lp(a) would be valid at strict LDL-C lowering therapy-treated patients with low LDL-C and high Lp(a).

As for the anti-atherosclerotic properties of apolipoproteins, some studies have reported on the relationship between ApoA-I and coronary plaques. A histopathological study revealed that ApoA-I levels correlated positively with tissue collagen and inversely with metalloproteinase-9 and macrophage contents in patients stable angina who underwent directional coronary atherectomy57. Also, ApoA-I levels were associated with less progression of atheroma volume58. As a prospective study on the ApoA-I and coronary plaques detected by IVUS showed that increasing levels of achieved HDL-C/ApoA-I ratio (p = 0.04), but not HDL-C (p = 0.18) or ApoA-I (p = 0.67), were associated with less progression of PAV measured by IVUS. Similar results were seen for change in total atheroma volume, with less progression seen with increased HDL-C/ApoA-I ratio (p = 0.002) but not with increases in HDL-C (p = 0.09) or ApoA-I (p = 0.19)59. In a basic research, it has been reported that poor regression of atherosclerotic plaques after LDL-C lowering in mice with diabetes mellitus can be overcome by raising levels of HDL particles by increasing expression of ApoA-I60. Whereas, oxidized HDL, which exhibited reduced CEC and anti-inflammatory properties, has been linked to high-risk plaques and significant stenosis detected by CCTA, as a marker of oxidized HDL/ApoA-I ratio61. HDL and ApoA-I recovered from human atheroma are dysfunctional and are extensively oxidized by myeloperoxidase. Myeloperoxidase accumulates within the subendothelial compartment, and mechanistically links to the formation of vulnerable plaques by mechanisms including catalytic consumption of nitric oxide, activation of matrix metalloproteinase pathways, and promotion of endothelial cell apoptosis and superficial erosions within culprit lesions62.

All ApoB-containing lipoproteins <70 nm in diameter, including Lp(a), LDL, smaller TRL, and their remnant particles, can cross the endothelial barrier, especially in the presence of endothelial dysfunction, where they can become trapped by interactions with extracellular structures such as proteoglycans63. Atherosclerotic plaques grow over time as ApoB-containing lipoprotein particles are retained. The total plaque burden is therefore influenced by the concentration of circulating LDL-C and other ApoB-containing lipoproteins, and by the total duration of exposure to these lipoproteins. Therefore, a person’s total atherosclerotic plaque burden is likely to be proportional to the cumulative exposure to these lipoproteins64. Eventually, the plaque burden and compositional changes may reach a critical point, leading to plaque disruption and formation of an overlying thrombus, which can obstruct blood flow resulting in unstable angina, myocardial infarction, or death. As a prospective study on the ApoB and coronary plaques detected by IVUS showed that multivariable analysis revealed that independently associated risk factors of progression in patients with LDL-C ≤ 70 mg/dL included baseline IVUS-derived PAV (p = 0.001), presence of diabetes mellitus (p = 0.02), increase in systolic blood pressure (p = 0.001), less increase in HDL-C (p = 0.01), and a smaller decrease in ApoB levels (p = 0.001)65. In addition, some studies have revealed that patients with high ApoB levels had longer lesion length, greater plaque volume, and a greater proportion of necrotic core as well as a lower proportion of calcified plaques in the culprit lesions using a virtual-histology IVUS compared with patients with low ApoB levels66,67. The association between ApoB and atheroma progression may highlight the potential importance of LDL particle concentration in patients with optimal LDL-C control. In addition, all the cholesterol within atheroma originates from ApoB particles, which enter and are trapped within the arterial wall, and ApoB particle is the basic unit of injury to the arterial wall. Thus, incorporating ApoB and Lp(a) into routine clinical care will improve assessment of cardiovascular risk due to the ApoB lipoproteins, and therapeutic intervention targeting ApoB may be able to achieve stronger lipid control.

Additionally, ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was a more sensitive predictor of the change in coronary plaque volume, than ApoB levels under strict lipid control using statins68. Also, an elevated ApoB/ApoA-I ratio was associated with OCT-derived presence of vulnerable plaques and thin-cap fibroatheroma69,70, and degree of coronary stenosis and increased non-calcified plaques detected by multidetector computed tomography71. ApoB/ApoA-I ratio reflects the balance between the “bad cholesterol particles and the good cholesterol particles”. Actually, the AMORIS study showed that ApoB, ApoB/ApoA-I ratio, and ApoA-I should be regarded as highly predictive in evaluation of fatal myocardial infarction risk72. Thus, the relationship between ApoB and ApoA-I could be of greatest value in diagnosis and treatment, and simultaneous quantitative correction of ApoB and qualitative improvement of ApoA-I through therapeutic intervention might lead to further advancement in ASCVD event avoidance.

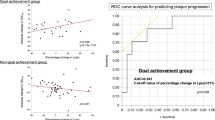

ApoC-III, either alone or with VLDL, promotes monocytes activation and adhesion to endothelial cells, playing a causal role in the development of atherosclerotic lesions73,74. ApoC-III levels are positively correlated with inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-1β75,76. These cytokines induce the expression of adhesion molecules such as vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, contributing to atherosclerosis and promoting calcification progression77,78. Also, ApoC-III increases vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression in human coronary artery endothelial cells; whereas, statins attenuate ApoC-III-induced monocyte adhesion79. As a randomized controlled trial on the ApoC-III and coronary plaques detected by NIRS-IVUS showed that both ApoC-III levels and NIRS-IVUS images at baseline and week 48 were analyzed in type 2 diabetic patients. Serial changes in IVUS-derived atheroma volume were similar between two groups (−0.7 ± 2.2 vs. −2.4 ± 1.6 mm3, p = 0.51); however, greater progression in NIRS-derived maxLCBI4mm was observed in those with any increase in ApoC-III levels (91.2 ± 24.8 vs. −44.2 ± 23.5, p < 0.001)80. In addition, some studies have investigated the relationship between ApoC-III and coronary artery calcification (CAC). These studies have found that elevated ApoC-III levels are associated with increased CAC detected by CCTA81, and elevated ApoC-III levels are associated with severe CAC and progression to calcified nodules82. Considering these reports, the main cause of atherosclerotic coronary plaque formation is LDL-C, and ApoC-III may synergistically promote plaque calcification and destabilization. Thus, it should be suggested ApoC-III as a residual risk that requires therapeutic intervention added to strict LDL-C lowering therapy.

Therapeutic advances

The current guidelines recommend that patients with ASCVD should receive LDL-C lowering therapy to target LDL-C levels <55 mg/dL, or at least <70 mg/dL in Japan17,83,84. LDL-C levels are mostly and directly involved in the development of atherosclerotic coronary plaques, and LDL-C lowering therapies, such as statins, ezetimibe, and proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors have contributed to coronary plaque regression85,86,87. We summarize the current clinical status of therapeutic agents targeting these apolipoproteins, as shown in Table 3.

Therapeutic agents targeting lipoprotein(a)

The treatments targeting Lp(a) have been gaining attention in recent years. The first Lp(a) studies in this field reported that lovastatin dose dependently increased Lp(a) levels by 33% or more88. The findings provided an initial indication that Lp(a), regardless of its structural similarity to LDL, may be cleared from plasma via a different pathway, and that statins may impact Lp(a) metabolism independent of its effect on LDLR. However, subsequent studies produced mixed results ranging from ineffectiveness to significant increases in Lp(a) levels with statins, raising questions regarding the consistency of findings89,90. In contrast, treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors reduces Lp(a)-associated Apo(a) production91, and contributes to reduction in NIRS-derived lipid rich plaques and CCTA-derived non-calcified necrotic plaques and pericoronary adipose tissue density92,93. The FOURIER trial revealed that PCSK9 inhibitors significantly reduced Lp(a) levels (median reduction 27%), and patients with higher baseline Lp(a) levels experienced greater absolute reductions and appeared to derive more pronounced coronary benefits94. In addition, several novel therapies, including oligonucleotide-based agents, are also in development, such as pelacarsen, olpasiran, zerlaciran, lepodisiran, and muvalaplin95,96,97,98,99. A phase II trial has shown that these agents can reduce plasma Lp(a) levels by >80–95% or more. These investigations are expected to reduce ASCVD risk and promote coronary plaque regression by targeting elevated Lp(a) levels.

Therapeutic agents targeting apolipoprotein A-I

Many large-scale clinical trials regarding drugs against ApoA-I have been conducted; however, there are many difficulties in applying them to clinical practice. The large-scale randomized clinical trials targeting pharmacological agents such as niacin and cholesteryl ester transfer protein inhibitors have shown that rising endogenous HDL-C does not improve cardiovascular outcomes or all-cause mortality100,101,102. These findings shifted the focus of research on HDL from quantity to quality, emphasizing the function of HDL particles rather than simply their cholesterol content. Against this background, ApoA-I, with its anti-arteriosclerotic effects, has been investigated as a therapeutic agent. One such example of this is recombinant ApoA-I Milano103, and ETC-216 contributed to the regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque in patients with acute coronary syndrome104; whereas, MDCO-216 had a no significant regression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque105. Recently, CSL112, a purified wild type ApoA-I preparation from human plasma, was developed. Infusion of CSL112 enhanced LCAT activity, increased plasma HDL-C levels, accelerated cholesterol esterification, and improved CEC in patients with acute myocardial infarction106. The AEGIS-II trial has demonstrated that four weekly infusions of CSL112 did not result in a lower risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes than a placebo after 90 days107. Although this trial did not meet its primary endpoint, exploratory analysis suggests that CSL112 may reduce cardiovascular death and myocardial, particularly in high-risk subgroups108. These findings support a potential clinical role for enhancing CEC in the management of coronary plaques.

Therapeutic agents targeting apolipoprotein B

The decreasing ApoB levels by statin therapy were associated with NIRS-derived lipid-rich plaques regression and IVUS-derived plaque burden regression109,110. Recently, the subanalysis of the HUYGENS has demonstrated that lower achieved ApoB levels (<65 mg/dL) associated with evidence of greater plaque stabilization even after controlling for LDL-C levels using PCSK9 inhibitors111. Although LDL-C and ApoB levels are usually closely correlated, LDL-C can underestimate ApoB in some cases, leaving residual cardiovascular risk. Therefore, when LDL-C and ApoB levels are discordant despite optimal lipid-lowering therapy, ApoB-targeted treatment targeting may be warranted. Mipomersen is a synthetic, single-stranded antisense oligonucleotide that binds the mRNA encoding ApoB-100, inhibiting its translation. Binding of mipomersen to ApoB-100 mRNA activates RNase H, which cleaves the RNA and prevents ApoB-100 protein synthesis, thereby lowering circulating ApoB levels112. The efficacy and safety of mipomersen have been studied in randomized clinical trials evaluating patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, or severe hypercholesterolemia113,114,115. However, due to its mechanism of blocking VLDL lipidation and secretion, which can cause hepatic TG accumulation, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black box warning for hepatotoxicity, and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) did not approve use of mipomersen. Thus, mipomersen is no longer available for clinical use.

Therapeutic agents targeting apolipoprotein C-III

While statins effectively prevent atherosclerosis through LDL-C lowering, agents targeting ApoC-III may further suppress the residual lipid-rich plaque as well as development and progression of CAC, including severe calcification and calcified nodules. In terms of pharmacological interventions for reducing ApoC-III levels, there have been reports on therapeutic agents that target TRL, such as fibrates, niacin, and omega-3 carboxylic acids. These agents have shown to reduce ApoC-III gene expression and circulating levels by between 10 and 40%116,117,118. Additionally, some studies have shown that volanesorsen, an antisense oligonucleotide that inhibits ApoC-III mRNA translation, can reduce ApoC-III levels by up to 70% in healthy individuals and 80% in patients with hyperglycemia119,120. Volanesorsen was approved by the EMA for use in patients with familial chylomicronemia syndrome, but was not approved by the FDA because of the risk of thrombocytopenia. While, olezarsen which is an N-acetylgalactosamine–conjugated antisense oligonucleotide that targets APOC3 messenger RNA, is approved by both EMA and FDA, and it has reported that treatment with olezarsen resulted in significantly greater reduction in TG levels at 6 months than placebo among patients with moderate hypertriglyceridemia and elevated ASCVD risk121. In addition, it has recently reported that both olezarsen for patients with severe hypertriglyceridemia and plozasiran for patients with persistent chylomicronemia have a significantly greater reduction in the TG level and in the incidence of acute pancreatitis than placebo122,123. Furthermore, the therapeutic agents targeting ANGPTL3, which has emerged as novel regulators of TG and LDL-C levels in a similar way to ApoC-III, are also being developed. Evinacumab, which has inhibited ANGPTL3, was approved in 2021 by both the EMA and FDA for the treatment of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia124. Zodasiran, a siRNA inhibiting ANGPTL3 mRNA, has not yet received the EMA and FDA approval (phase 3 randomized controlled trial ongoing). Previous studies have shown that lipid metabolism related to ApoC-III has a strong effect on CAC and lipid-rich plaque, so it is expected that these therapeutic agents will contribute to the correction of lesion complexity and plaque instability.

Conclusions

We have reviewed the pathophysiological roles and genetic insights, imaging correlates, and therapeutic advance of Apo(a), ApoA-I, ApoB, and ApoC-III. The atherogenicity of Lp(a) is substantially greater than that of LDL on a per-particle basis, and elevated Lp(a) has been established as an independent risk factor for ASCVD, particularly in individuals with high LDL-C. Several novel therapies, including oligonucleotide-based agents, are in development to target elevated Lp(a), and are anticipated to provide significant clinical benefits. Although ApoA-I plays a central role in reverse cholesterol transport, and contributes to anti-atherosclerotic activity through CEC, therapeutic drugs targeting ApoA-I have not yet to be applied clinically, so we look forward to future developments. While, ApoB serves as a stronger indicator of necrotic core size and a potential biomarker for unstable plaque, compared to LDL-C. Thus, the European Society of Cardiology recommended ApoB measurement for risk assessment, particularly in patients with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes mellitus, obesity, metabolic syndromes, or very low LDL-C. Therefore, the establishment of a treatment targeting ApoB is thought to be of great clinical significance; however, mipomersen is unfortunately no longer available for clinical use, due to critical adverse effect of hepatotoxicity. In addition, ApoC-III acts as key determinants of intravascular lipolysis and the clearance of TG-rich chylomicron and VLDL from plasma, thereby influencing atherosclerotic function as CAC and lipid core progression under strict lipid control; thus, further research into the effects of therapeutic intervention targeting ApoC-III on atherosclerotic coronary plaques and ASCVD events is anticipated; for instance, randomized trials on the effects of therapeutic agents targeting apolipoprotein C-III on coronary plaque regression and stabilization. Taken together, the remarkable progress in understanding apolipoproteins offers the potential for more comprehensive and precise strategies to prevent plaque progression and coexisting ASCVD onset.

Data availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author with reasonable request.

References

Virani, S. S. et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2021 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 143, e254–e743 (2021).

Ference, B. A. et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 38, 2459–2472 (2017).

Doi, T., Langsted, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Lipoproteins, cholesterol, and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in East Asians and Europeans. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 30, 1525–1546 (2023).

Ahmed, S., Pande, A. H. & Sharma, S. S. Therapeutic potential of ApoE-mimetic peptides in CNS disorders: current perspective. Exp. Neurol. 353, 114051 (2022).

Gordon, S. M. et al. Identification of a novel lipid binding motif in apolipoprotein B by the analysis of hydrophobic cluster domains. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1859, 135–145 (2017).

Pownall, H. J., Rosales, C., Gillard, B. K. & Ferrari, M. Native and reconstituted plasma lipoproteins in nanomedicine: physicochemical determinants of nanoparticle structure, stability, and metabolism. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc. J. 12, 146–150 (2016).

Tao, X., Tao, R., Wang, K. & Wu, L. Anti-inflammatory mechanism of Apolipoprotein A-I. Front. Immunol. 15, 1417270 (2024).

Di, L. & Maiseyeu, A. Low-density lipoprotein nanomedicines: mechanisms of targeting, biology, and theranostic potential. Drug Deliv. 28, 408–421 (2021).

Frank, P. G. & Marcel, Y. L. Apolipoprotein A-I: structure-function relationships. J. Lipid Res. 41, 853–872 (2000).

Musliner, T. A., Herbert, P. N. & Church, E. C. Activation of lipoprotein lipase by native and acylated peptides of apolipoprotein C-II. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 573, 501–509 (1979).

Li, Y. et al. Apolipoproteins as potential communicators play an essential role in the pathogenesis and treatment of early atherosclerosis. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 19, 4493–4510 (2023).

Kronenberg, F. Human genetics and the causal role of Lipoprotein(a) for various diseases. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 30, 87–100 (2016).

Kronenberg, F. & Utermann, G. Lipoprotein(a): resurrected by genetics. J. Intern. Med. 273, 6–30 (2013).

Tsimikas, S. A test in context: Lipoprotein(a): diagnosis, prognosis, controversies, and emerging therapies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 69, 692–711 (2017).

Schmidt, K., Noureen, A., Kronenberg, F. & Utermann, G. Structure, function, and genetics of lipoprotein (a). J. Lipid Res. 57, 1339–1359 (2016).

Gaubatz, J. W., Heideman, C., Gotto, A. M. Jr., Morrisett, J. D. & Dahlen, G. H. Human plasma lipoprotein [a]. Structural properties. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 4582–4589 (1983).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 111–188 (2020).

Pearson, G. J. et al. 2021 Canadian cardiovascular society guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in adults. Can. J. Cardiol. 37, 1129–1150 (2021).

Tsimikas, S. et al. NHLBI Working Group recommendations to reduce Lipoprotein(a)-mediated risk of cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 71, 177–192 (2018).

Sorci-Thomas, M. G. & Thomas, M. J. The effects of altered apolipoprotein A-I structure on plasma HDL concentration. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 12, 121–128 (2002).

Mangaraj, M., Nanda, R. & Panda, S. Apolipoprotein A-I: a molecule of diverse function. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 31, 253–259 (2016).

Toth, P. P. et al. High-density lipoproteins: a consensus statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipido. 7, 484–525 (2013).

Bojanovski, D. et al. In vivo metabolism of proapolipoprotein A-I in Tangier disease. J. Clin. Investig. 80, 1742–1747 (1987).

Sakai, N. et al. Targeted disruption of the mouse lecithin: cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) gene. Generation of a new animal model for human LCAT deficiency. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 7506–7510 (1997).

Wang, N., Lan, D., Chen, W., Matsuura, F. & Tall, A. R. ATP-binding cassette transporters G1 and G4 mediate cellular cholesterol efflux to high-density lipoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9774–9779 (2004).

Acton, S. et al. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science 271, 518–520 (1996).

Olofsson, S. O. & Borèn, J. Apolipoprotein B: a clinically important apolipoprotein which assembles atherogenic lipoproteins and promotes the development of atherosclerosis. J. Intern. Med. 258, 395–410 (2005).

Morita, S. Y. Metabolism and modification of apolipoprotein B-Containing lipoproteins involved in dyslipidemia and atherosclerosis. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 39, 1–24 (2016).

Avramoglu, R. K. & Adeli, K. Hepatic regulation of apolipoprotein B. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 5, 293–301 (2004).

Nakajima, K. et al. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism: VLDL vs chylomicrons. Clin. Chim. Acta 412, 1306–1318 (2011).

Contois, J. H. et al. Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease risk: position statement from the AACC Lipoproteins and Vascular Diseases Division Working Group on Best Practices. Clin. Chem. 55, 407–419 (2009).

Cooper, A. D. Hepatic uptake of chylomicron remnants. J. Lipid Res. 38, 2173–2192 (1997).

Sakai, N. et al. Measurement of fasting serum apoB-48 levels in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic subjects by ELISA. J. Lipid Res. 44, 1256–1262 (2003).

Vinagre, C. G. et al. Removal of chylomicron remnants from the bloodstream is delayed in aged subjects. Aging Dis. 9, 748–754 (2018).

Masuda, D. et al. Reference interval for the apolipoprotein B-48 concentration in healthy Japanese individuals. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 21, 618–627 (2014).

Doonan, L. M., Fisher, E. A. & Brodsky, J. L. Can modulators of apolipoproteinB biogenesis serve as an alternate target for cholesterol-lowering drugs?. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1863, 762–771 (2018).

Behbodikhah, J. et al. Apolipoprotein B and cardiovascular disease: biomarker and potential therapeutic target. Metabolites 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11100690 (2021).

Sniderman, A., Vu, H. & Cianflone, K. Effect of moderate hypertriglyceridemia on the relation of plasma total and LDL apo B levels. Atherosclerosis 89, 109–116 (1991).

Mehta, A. & Shapiro, M. D. Apolipoproteins in vascular biology and atherosclerotic disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 168–179 (2022).

van Dijk, K. W., Rensen, P. C., Voshol, P. J. & Havekes, L. M. The role and mode of action of apolipoproteins CIII and AV: synergistic actors in triglyceride metabolism?. Curr. Opin. Lipido. 15, 239–246 (2004).

D’Erasmo, L., Di Costanzo, A., Gallo, A., Bruckert, E. & Arca, M. ApoCIII: a multifaceted protein in cardiometabolic disease. Metabolism 113, 154395 (2020).

Huded, C. P. et al. Association of serum lipoprotein (a) levels and coronary atheroma volume by intravascular ultrasound. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e018023 (2020).

Kaiser, Y. et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) with atherosclerotic plaque progression. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79, 223–233 (2022).

Lan, Z. et al. Impact of lipoprotein (a) on coronary atherosclerosis and plaque progression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Eur. Radio. 35, 1533–1542 (2025).

Nurmohamed, N. S. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and long-term plaque progression, low-density plaque, and pericoronary inflammation. JAMA Cardiol. 9, 826–834 (2024).

Yu, M. M. et al. Association of lipoprotein(a) levels with myocardial infarction in patients with low-attenuation plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 1743–1755 (2024).

Yang, X. et al. CCTA-quantified pericornary inflammation and lipoprotein (a): combined predictive value in non-obstructive CAD. Int. J. Cardiol. 442, 133887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2025.133887 (2026).

Hikita, H. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is an important factor to determine coronary artery plaque morphology in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Coron. Artery Dis. 24, 381–385 (2013).

Wang, Y. F. et al. The Effect of Lipoprotein(a) levels on non-culprit atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndrome who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention: an optical coherence tomography study. Catheter Cardiovasc. Inter. 106, 633–643 (2025).

Di Muro, F. M. et al. Coronary plaque characteristics assessed by optical coherence tomography and plasma lipoprotein(a) levels in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Catheter Cardiovasc. Inter. 106, 64–72 (2025).

Niccoli, G. et al. Lipoprotein (a) is related to coronary atherosclerotic burden and a vulnerable plaque phenotype in angiographically obstructive coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 246, 214–220 (2016).

Nozue, T. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is associated with necrotic core progression of non-culprit coronary lesions in statin-treated patients with angina pectoris. Lipids Health Dis. 13, 59 (2014).

Matsushita, K. et al. Impact of serum lipoprotein (a) level on coronary plaque progression and cardiovascular events in statin-treated patients with acute coronary syndrome: a yokohama-acs substudy. J. Cardiol. 76, 66–72 (2020).

Shishikura, D. et al. Characterization of lipidic plaque features in association with LDL-C<70 mg/dL and lipoprotein(a) <50 mg/dL. J. Clin. Lipido. 19, 509–520 (2025).

Puri, R. et al. Lipoprotein(a) and coronary atheroma progression rates during long-term high-intensity statin therapy: Insights from SATURN. Atherosclerosis 263, 137–144 (2017).

Erlinge, D. et al. Lipoprotein(a), Cholesterol, triglyceride levels, and vulnerable coronary plaques: a PROSPECT II substudy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 85, 2011–2024 (2025).

Solem, J. et al. Composition of coronary plaques obtained by directional atherectomy in stable angina: its relation to serum lipids and statin treatment. J. Intern. Med. 259, 267–275 (2006).

Bamberg, F. et al. Differential associations between blood biomarkers of inflammation, oxidation, and lipid metabolism with varying forms of coronary atherosclerotic plaque as quantified by coronary CT angiography. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 28, 183–192 (2012).

Mani, P. et al. Relation of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol:apolipoprotein a-I ratio to progression of coronary atherosclerosis in statin-treated patients. Am. J. Cardiol. 114, 681–685 (2014).

Barrett, T. J. et al. Apolipoprotein AI promotes atherosclerosis regression in diabetic mice by suppressing myelopoiesis and plaque inflammation. Circulation 140, 1170–1184 (2019).

Suruga, K. et al. Higher oxidized high-density lipoprotein to apolipoprotein A-I ratio is associated with high-risk coronary plaque characteristics determined by CT angiography. Int. J. Cardiol. 324, 193–198 (2021).

Huang, Y. et al. An abundant dysfunctional apolipoprotein A1 in human atheroma. Nat. Med. 20, 193–203 (2014).

Tabas, I., Williams, K. J. & Borén, J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation 116, 1832–1844 (2007).

Ference, B. A., Graham, I., Tokgozoglu, L. & Catapano, A. L. Impact of Lipids on cardiovascular health: JACC health promotion series. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 1141–1156 (2018).

Bayturan, O. et al. Clinical predictors of plaque progression despite very low levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55, 2736–2742 (2010).

Voros, S. et al. Apoprotein B, small-dense LDL and impaired HDL remodeling is associated with larger plaque burden and more noncalcified plaque as assessed by coronary CT angiography and intravascular ultrasound with radiofrequency backscatter: results from the ATLANTA I study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2, e000344 (2013).

Ohwada, T. et al. Apolipoprotein B correlates with intra-plaque necrotic core volume in stable coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE 14, e0212539 (2019).

Tani, S. et al. Relation of change in apolipoprotein B/apolipoprotein A-I ratio to coronary plaque regression after Pravastatin treatment in patients with coronary artery disease. Am. J. Cardiol. 105, 144–148 (2010).

Deng, F. et al. Association between apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio and coronary plaque vulnerability in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: an intravascular optical coherence tomography study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 20, 188 (2021).

Du, Y. et al. Association between apolipoprotein B/A1 ratio and quantities of tissue prolapse on optical coherence tomography examination in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 40, 545–555 (2024).

Jung, C. H. et al. Association of apolipoprotein b/apolipoprotein A1 ratio and coronary artery stenosis and plaques detected by multi-detector computed tomography in healthy population. J. Korean Med. Sci. 28, 709–716 (2013).

Walldius, G. et al. High apolipoprotein B, low apolipoprotein A-I, and improvement in the prediction of fatal myocardial infarction (AMORIS study): a prospective study. Lancet 358, 2026–2033 (2001).

Kawakami, A. et al. Apolipoprotein CIII induces expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 in vascular endothelial cells and increases adhesion of monocytic cells. Circulation 114, 681–687 (2006).

Kawakami, A. et al. Apolipoprotein CIII in apolipoprotein B lipoproteins enhances the adhesion of human monocytic cells to endothelial cells. Circulation 113, 691–700 (2006).

Chen, L. et al. Association of plasma apolipoprotein CIII, high sensitivity C-reactive protein and tumor necrosis factor-α contributes to the clinical features of coronary heart disease in Li and Han ethnic groups in China. Lipids Health Dis. 17, 176 (2018).

Zewinger, S. et al. Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 21, 30–41 (2020).

Luo, S. F. et al. Involvement of MAPKs and NF-kappaB in tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 expression in human rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum. 62, 105–116 (2010).

Nakahara, T. et al. Coronary artery calcification: from mechanism to molecular imaging. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 10, 582–593 (2017).

Zheng, C. et al. Statins suppress apolipoprotein CIII-induced vascular endothelial cell activation and monocyte adhesion. Eur. Heart J. 34, 615–624 (2013).

Kitahara, S. et al. Apolipoprotein CIII in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients: Its implications for plaque progression and instability: the pre-specified analysis from the OPTIMAL randomized controlled trial. Atherosclerosis 409, 120470 (2025).

Qamar, A. et al. Plasma apolipoprotein C-III levels, triglycerides, and coronary artery calcification in type 2 diabetics. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 35, 1880–1888 (2015).

Fukase, T. et al. Association between apolipoprotein C-III levels and coronary calcification detected by intravascular ultrasound in patients who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 11, 1430203 (2024).

Kinoshita, M. et al. Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) Guidelines for Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Diseases 2017. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 25, 846–984 (2018).

Grundy, S. M. et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the management of blood cholesterol: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 139, e1082–e1143 (2019).

Okazaki, S. et al. Early statin treatment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: demonstration of the beneficial effect on atherosclerotic lesions by serial volumetric intravascular ultrasound analysis during half a year after coronary event: the ESTABLISH Study. Circulation 110, 1061–1068 (2004).

Tsujita, K. et al. Impact of dual lipid-lowering strategy with ezetimibe and atorvastatin on coronary plaque regression in patients with percutaneous coronary intervention: the multicenter randomized controlled PRECISE-IVUS Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 66, 495–507 (2015).

Nicholls, S. J. et al. Effect of evolocumab on coronary plaque phenotype and burden in statin-treated patients following myocardial infarction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 15, 1308–1321 (2022).

Kostner, G. M. et al. HMG CoA reductase inhibitors lower LDL cholesterol without reducing Lp(a) levels. Circulation 80, 1313–1319 (1989).

Hunninghake, D. B., Stein, E. A. & Mellies, M. J. Effects of one year of treatment with pravastatin, an HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor, on lipoprotein a. J. Clin. Pharm. 33, 574–580 (1993).

Haffner, S., Orchard, T., Stein, E., Schmidt, D. & LaBelle, P. Effect of simvastatin on Lp(a) concentrations. Clin. Cardiol. 18, 261–267 (1995).

Watts, G. F. et al. Factorial effects of evolocumab and atorvastatin on lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation 135, 338–351 (2017).

Koskinas, K. C. et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) with changes in coronary atherosclerosis in patients treated with alirocumab. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 17, e016683 (2024).

Yu, M. M. et al. Evolocumab attenuate pericoronary adipose tissue density via reduction of lipoprotein(a) in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a serial follow-up CCTA study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 22, 121 (2023).

O’Donoghue, M. L. et al. Lipoprotein(a), PCSK9 Inhibition, and cardiovascular Risk. Circulation 139, 1483–1492 (2019).

Tsimikas, S. et al. Lipoprotein(a) reduction in persons with cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 244–255 (2020).

O’Donoghue, M. L. et al. Small interfering RNA to reduce lipoprotein(a) in cardiovascular disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1855–1864 (2022).

Nissen, S. E. et al. Zerlasiran-A small-interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a): a phase 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 332, 1992–2002 (2024).

Nissen, S. E. et al. Lepodisiran - a long-duration small interfering RNA targeting lipoprotein(a). N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 1673–1683 (2025).

Nicholls, S. J. et al. Oral muvalaplin for lowering of lipoprotein(a): a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 333, 222–231 (2025).

Barter, P. J. et al. Effects of torcetrapib in patients at high risk for coronary events. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2109–2122 (2007).

Landray, M. J. et al. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 203–212 (2014).

Schwartz, G. G. et al. Effects of dalcetrapib in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 2089–2099 (2012).

Franceschini, G., Sirtori, C. R., Capurso, A. 2nd, Weisgraber, K. H. & Mahley, R. A-IMilano apoprotein. Decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol levels with significant lipoprotein modifications and without clinical atherosclerosis in an Italian family. J. Clin. Investig. 66, 892–900 (1980).

Nissen, S. E. et al. Effect of recombinant ApoA-I Milano on coronary atherosclerosis in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 290, 2292–2300 (2003).

Nicholls, S. J. et al. Effect of infusion of high-density lipoprotein mimetic containing recombinant apolipoprotein A-I milano on coronary disease in patients with an acute coronary syndrome in the MILANO-PILOT trial: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 806–814 (2018).

Mathias, R. A. et al. Apolipoprotein A1 (CSL112) increases lecithin-cholesterol acyltransferase levels in HDL particles and promotes reverse cholesterol transport. JACC Basic Transl. Sci. 10, 405–418 (2025).

Gibson, C. M. et al. Apolipoprotein A1 infusions and cardiovascular outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. N. Engl. J. Med. 390, 1560–1571 (2024).

Povsic, T. J. et al. Effect of reconstituted human apolipoprotein A-I on recurrent ischemic events in survivors of acute MI. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 2163–2174 (2024).

Funabashi, S. et al. Circulating apolipoprotein B levels in statin-treated type 2 diabetic patients with coronary artery disease: implications for coronary atheroma progression and instability. J. Clin. Lipido. 19, 888–898 (2025).

Arai, H. et al. More intensive lipid lowering is associated with regression of coronary atherosclerosis in diabetic patients with acute coronary syndrome–sub-analysis of JAPAN-ACS study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 17, 1096–1107 (2010).

Fujino, M. et al. Achieved levels of apolipoprotein B and plaque composition after acute coronary syndromes: Insights from HUYGENS. Atherosclerosis 403, 119145 (2025).

Wong, E. & Goldberg, T. Mipomersen (kynamro): a novel antisense oligonucleotide inhibitor for the management of homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Pharm. Ther. 39, 119–122 (2014).

Raal, F. J. et al. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, for lowering of LDL cholesterol concentrations in patients with homozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 375, 998–1006 (2010).

Stein, E. A. et al. Apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibition with mipomersen in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia: results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial to assess efficacy and safety as add-on therapy in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 126, 2283–2292 (2012).

Thomas, G. S. et al. Mipomersen, an apolipoprotein B synthesis inhibitor, reduces atherogenic lipoproteins in patients with severe hypercholesterolemia at high cardiovascular risk: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 2178–2184 (2013).

de Man, F. H. et al. The hypolipidemic action of bezafibrate therapy in hypertriglyceridemia is mediated by upregulation of lipoprotein lipase: no effects on VLDL substrate affinity to lipolysis or LDL receptor binding. Atherosclerosis 153, 363–371 (2000).

Hernandez, C., Molusky, M., Li, Y., Li, S. & Lin, J. D. Regulation of hepatic ApoC3 expression by PGC-1β mediates hypolipidemic effect of nicotinic acid. Cell Metab. 12, 411–419 (2010).

Dunbar, R. L. et al. Effects of omega-3 carboxylic acids on lipoprotein particles and other cardiovascular risk markers in high-risk statin-treated patients with residual hypertriglyceridemia: a randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. Lipids Health Dis. 14, 98 (2015).

Graham, M. J. et al. Antisense oligonucleotide inhibition of apolipoprotein C-III reduces plasma triglycerides in rodents, nonhuman primates, and humans. Circ. Res. 112, 1479–1490 (2013).

Yang, X. et al. Reduction in lipoprotein-associated apoC-III levels following volanesorsen therapy: phase 2 randomized trial results. J. Lipid Res. 57, 706–713 (2016).

Bergmark, B. A. et al. Targeting APOC3 with Olezarsen in moderate hypertriglyceridemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 393, 1279–1291 (2025).

Marston, N. A. et al. Olezarsen for managing severe hypertriglyceridemia and pancreatitis risk. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2512761 (2025).

Watts, G. F. et al. Plozasiran for managing persistent chylomicronemia and pancreatitis risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 127–137 (2025).

Raal, F. J. et al. Evinacumab for homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 711–720 (2020).

Rosenson, R. S. et al. Lipoprotein (a) integrates monocyte-mediated thrombosis and inflammation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J. Lipid Res. 66, 100820 (2025).

Björnson, E. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is markedly more atherogenic than LDL: an apolipoprotein B-based genetic analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 385–395 (2024).

Takahashi, D. et al. Impact of Lipoprotein(a) as a residual risk factor in long-term cardiovascular outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndrome treated with statins. Am. J. Cardiol. 168, 11–16 (2022).

Takahashi, N. et al. Prognostic impact of lipoprotein (a) on long-term clinical outcomes in diabetic patients on statin treatment after percutaneous coronary intervention. J. Cardiol. 76, 25–29 (2020).

James, R. W. et al. Protein heterogeneity of lipoprotein particles containing apolipoprotein A-I without apolipoprotein A-II and apolipoprotein A-I with apolipoprotein A-II isolated from human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 29, 1557–1571 (1988).

Martin, S. S. et al. HDL cholesterol subclasses, myocardial infarction, and mortality in secondary prevention: the lipoprotein investigators collaborative. Eur. Heart J. 36, 22–30 (2015).

Fukase, T. et al. Combined impacts of low apolipoprotein A-I levels and reduced renal function on long-term prognosis in patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Clin. Chim. Acta 536, 180–190 (2022).

Saleheen, D. et al. Association of HDL cholesterol efflux capacity with incident coronary heart disease events: a prospective case-control study. Lancet Diab. Endocrinol. 3, 507–513 (2015).

Sniderman, A. D., Islam, S., Yusuf, S. & McQueen, M. J. Discordance analysis of apolipoprotein B and non-high density lipoprotein cholesterol as markers of cardiovascular risk in the INTERHEART study. Atherosclerosis 225, 444–449 (2012).

Pencina, M. J. et al. Apolipoprotein B improves risk assessment of future coronary heart disease in the Framingham Heart Study beyond LDL-C and non-HDL-C. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 22, 1321–1327 (2015).

Wilkins, J. T., Li, R. C., Sniderman, A., Chan, C. & Lloyd-Jones, D. M. discordance between apolipoprotein B and LDL-cholesterol in young adults predicts coronary artery calcification: the CARDIA study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 67, 193–201 (2016).

Lawler, P. R. et al. Discordance between circulating atherogenic cholesterol mass and lipoprotein particle concentration in relation to future coronary events in women. Clin. Chem. 63, 870–879 (2017).

Welsh, C. et al. Comparison of conventional lipoprotein tests and apolipoproteins in the prediction of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 140, 542–552 (2019).

Wyler von Ballmoos, M. C., Haring, B. & Sacks, F. M. The risk of cardiovascular events with increased apolipoprotein CIII: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Lipido. 9, 498–510 (2015).

van Capelleveen, J. C. et al. Apolipoprotein C-III levels and incident coronary artery disease risk: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Arterioscler Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 37, 1206–1212 (2017).

Scheffer, P. G. et al. Increased plasma apolipoprotein C-III concentration independently predicts cardiovascular mortality: the Hoorn Study. Clin. Chem. 54, 1325–1330 (2008).

Hussain, A. et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, apolipoprotein C-III, angiopoietin-like protein 3, and cardiovascular events in older adults: Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 29, e53–e64 (2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: T.F. and T.D. Data curation: T.F. and T.D. Investigation: T.F., and T.D. Methodology: T.F. and T.D. Supervision: T.D. Drafting of the manuscript: T.F. Writing—review and editing: T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fukase, T., Dohi, T. A narrative review of impacts of apolipoproteins on atherosclerotic coronary plaques. npj Cardiovasc Health 3, 4 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-026-00104-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44325-026-00104-x