Abstract

Biofilms, notorious for their recalcitrance and dynamic behavior, pose a persistent threat to public health. However, existing diagnostic tools fall short in providing in situ, spatiotemporal biochemical insights into dynamic biofilm behavior. To address this, we have developed zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes that combine the antifouling attributes of zwitterionic L-cysteine, the biocompatibility of polymeric meshes, and the ultrasensitive, uniform, and stable surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) response of plasmonic nanocavity arrays. This platform delivers improved SERS performance in human serum compared to controls without L-cysteine functionalization, achieving a clinically-relevant limit of detection of 5.6 nM for pyocyanin in undiluted human serum. Moreover, the platform enables real-time, in situ spatiotemporal SERS monitoring of P. aeruginosa biofilms over 48 h in culture media-agar backgrounds, revealing distinct pyocyanin secretions dynamics in wild-type and hyperbiofilm mutant strains. We envision that this capability to non-invasively monitor biofilm metabolite secretion dynamics can empower next-generation biofilm diagnostics and anti-biofilm therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biofilms, microbial communities embedded in a self-produced extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) matrix1, pose a persistent threat across healthcare, industry, and the environment2,3. Their recalcitrance to conventional antimicrobial therapies enables them to establish chronic infections, leading to substantial clinical and economic repercussions2,3,4. Consequently, development of advanced monitoring tools that provide real-time, in-depth information about biofilm behavior is essential for creating effective control and treatment strategies5. For instance, real-time monitoring of secreted metabolites (e.g., phenazines such as pyocyanin), can help to correlate metabolite levels with interdependent bacterial mechanisms such as genetic mutations6, signaling7,8, and biofilm development9,10 for developing targeted therapies. Furthermore, the dynamic and heterogeneous nature of biofilms necessitates monitoring techniques capable of non-invasively and spatiotemporally capturing their system-level biochemical activities in situ. This capability is pivotal for understanding complex interactions within biofilm communities and their interplay with host tissues and therapeutic interventions11,12,13.

Conventional laboratory methods, such as microbial culture and molecular diagnostics, while valuable, often lack real-time, in situ data indispensable for effective clinical management of biofilm infections14. These techniques typically involve invasive sampling, time-consuming bioanalysis workflows, and disruption of the biofilm’s natural environment. The advent of bio-interfaced, biocompatible, and label-free biosensor technologies has enabled real-time, in situ biofilm monitoring in clinically relevant settings, utilizing electrical, optical, or mechanical readouts5,15. However, these techniques often lack the molecular specificity and continuous detection capabilities required to distinguish and track specific molecular constituents and their production over time, thus constraining their ability to fully elucidate the dynamic molecular landscape of biofilms.

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS)16, known for its exceptional nanoplasmonic sensitivity and biochemical specificity, has shown promise for real-time, in situ detection of specific biomolecules within biofilms, potentially offering insights into their composition and biochemical dynamics17,18,19,20,21. However, translating SERS to in situ spatiotemporal biochemical monitoring of biofilms in clinically relevant settings faces several obstacles, including: (i) fabricating large-area, high-density arrays of biocompatible and mechanically robust nanoplasmonic hotspots, (ii) developing flexible and porous device form factors that can seamlessly interface with living systems, and (iii) mitigating protein biofouling at hotspots to ensure long-term SERS sensitivity during in situ spatiotemporal monitoring.

To address these challenges, this study introduces zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes that combine the antifouling attributes of zwitterionic L-cysteine22,23, the biocompatibility of polymeric meshes (Supplementary Text 1)24, and the ultrasensitive, uniform, and stable SERS response of plasmonic nanocavity arrays25. We demonstrate the capability of our zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-mesh platform by effectively detecting pyocyanin, a signaling molecule and pathogenicity factor secreted by the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, at clinically relevant concentrations (5.6 nM) in undiluted human serum. Moreover, the platform empowers real-time, in situ spatiotemporal SERS biochemical monitoring of P. aeruginosa biofilms over 48 h, providing insights into biofilm growth and pyocyanin production dynamics in wild type and a hyperbiofilm mutant.

Results

Zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-mesh fabrication, characterization, and antifouling demonstration

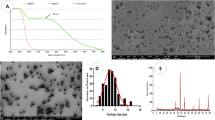

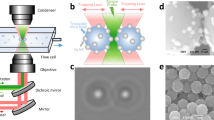

Fig. 1A illustrates the fabrication process of our zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes using high-throughput soft reverse nanoimprint lithography18 (Supplementary Text 2). Briefly, the process involves two key parts: (1) transferring a nanohole array pattern onto lithographically defined polymeric meshes, and (2) depositing alternating layers of gold and SiO2, followed by resist stripping and partial etching of the SiO2 layers. This process results in the formation of nanolaminate plasmonic nanoantenna (NLPNA) arrays with metal-insulator-metal nanocavities, which are firmly attached to the polymeric mesh. To confer antifouling properties, the Au surfaces of NLPNAs were functionalized with L-cysteine. At physiological pH, this naturally occurring amino acid is zwitterionic, possessing both positive (amino) and negative (carboxyl) charges. This inherent charge balance minimizes non-specific electrostatic attraction with proteins and concurrently facilitates the formation of a tightly bound hydration layer through strong electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding with surrounding water molecules26,27. This hydration layer constitutes a physical and energetic barrier; proteins must overcome a significant energetic penalty to displace these structured water molecules, effectively hindering protein adsorption23. The small thickness of the L-cysteine monolayer (<1 nm)28 and its associated hydration layer should permit sufficient spatial access for small analytes to access the 8–12 nm wide plasmonic nanogap hotspot openings. Consequently, this mechanism preserves the accessibility of the SERS-active surface for the detection of small target analytes (Fig. 1A). Additionally, its strong thiol bond to gold surface promotes stability (Fig. 1A)22. Fig. 1B shows characteristic images illustrating the uniform distribution of multilayered NLPNA arrays on the biocompatible polymeric mesh. These nanoplasmonic bio-meshes exhibit high SERS enhancement factors (~107) with good spatial uniformity (relative standard deviation = 12.3%) (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Text 1), along with biocompatible mechanical properties (Supplementary Text 1 and 4), making them well suited for bio-interfaced spatiotemporal SERS monitoring applications (Supplementary Text 1 and 4).

A Schematic illustration of the zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-mesh fabrication process, highlighting the use of reverse nanoimprint lithography and the mechanism by which L-cysteine self-assembled monolayers on nanolaminated plasmonic nanoantennas (NLPNAs) confer antifouling properties. B Visual and microscopic characterization of zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes: Oblique-angle and top-down camera images showcasing macroscopic features, top-down bright-field and SEM images revealing surface morphology, and cross-sectional SEM image alongside a schematic illustrating the NLPNA structure. C Experimental timeline depicting the sequential exposure of SERS devices to serum, water, and R6G-spiked serum, with green regions indicating active SERS measurement periods. D Comparative ERS-normalized SERS spectra of L-cysteine-functionalized and bare SERS devices in serum, water, and R6G-spiked serum, highlighting the impact of L-cysteine on protein fouling and R6G detection. Shaded regions represent standard deviations from 50 individual spectra. E Time-resolved ERS-normalized intensities of characteristic Raman peaks for serum protein (1245 cm⁻¹) and R6G (1507 cm⁻¹) in different solutions, further demonstrating the antifouling efficacy of L-cysteine functionalization. Error bars represent standard deviations from 50 datapoints. *** represents p values < 0.001, indicating statistically significant difference. F Time-resolved 2D maps of the characteristic ERS-normalized Raman peak for serum protein (1245 cm⁻¹) in different solutions.

To highlight the crucial role of zwitterionic L-cysteine functionalization in protein-rich environments, we employed Rhodamine 6G as a model analyte to assess SERS hotspot accessibility (Supplementary Text 1). As outlined in Fig. 1C, both L-cysteine-functionalized and bare SERS devices were sequentially exposed to undiluted human serum (10 min), deionized water (10 min), and human serum spiked with 10 μM R6G (10 min). Time-dependent SERS area maps were acquired throughout the 30 min experiment. Fig. 1D shows the SERS spectra at 10, 15, and 30 min, showcasing the spectral evolution in serum, water, and R6G-spiked serum, respectively. Raman peak signal intensities were calibrated with the electronic Raman scattering (ERS) internal standard throughout this paper29. In the bare devices, prominent peaks from serum proteins such as albumin (730, 845, 1000, 1082, 1110, 1185, 1245, 1289, 1360, 1462, 1540, and 1589 cm-1) indicated protein occupation at hotspots (Supplementary Table 1). These peaks persisted even after water rinsing, confirming protein fouling of bare SERS devices. In contrast, the cysteine-functionalized SERS devices exhibited weaker serum protein peaks. Upon exposure to R6G-spiked serum, R6G peaks at 1191, 1310, 1365, and 1507 cm-1 were detected in both samples (Fig. 1D)30. Fig. 1E, F and Supplementary Fig. 2B further quantify these effects by tracking the spatiotemporal evolution of the protein peaks (1245 and 1000 cm⁻¹) and the R6G peak (1507 cm⁻¹). In the bare device, the intensity of the protein peak continued to increase over time and persisted even after rinsing, indicating fouling. However, the cysteine-functionalized device maintained a stable baseline, with a reduction in intensity after washing and upon the introduction of R6G. This suggests that the R6G molecules could freely compete for hotspots due to the minimized protein fouling. Additionally, the cysteine-functionalized device exhibited stronger R6G peaks, which intensified over time, indicating enhanced access and adsorption of R6G at the SERS hotspots. These results collectively suggest that L-cysteine has antifouling properties against serum proteins over 30 min, crucial for preserving SERS sensitivity and enabling reliable biochemical detection in complex biological milieux.

Pyocyanin detection in human serum

To highlight the clinical potential of L-cysteine antifouling strategy, we assessed the detection limit of pyocyanin, a key pathogenicity factor secreted by P. aeruginosa, in undiluted human serum using the zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes. Pyocyanin’s resonant Raman behavior at the 785 nm laser excitation21, coupled with the plasmonic nanocavity field enhancement, enables exceptional detection sensitivity. Fig. 2A presents the ERS-calibrated averaged SERS spectra of human serum spiked with increasing pyocyanin concentrations (10-5 to 10-9M). We observed distinct pyocyanin Raman peaks (e.g., 410, 545, 590, 676, 1249, 1350 cm-1), alongside peaks at 845, 1000, 1082, 1185 and 1245 cm-1 attributed to serum proteins (Supplementary Table 1). Notably, at lower pyocyanin concentrations, we observe an increase in the serum protein peak intensity at 1000 cm-1 which lies in a pyocyanin-silent spectral region and a corresponding decrease in the intensity of pyocyanin peaks at 545 and 1350 cm-1 (Fig. 2B, C, Supplementary Fig. 3). This inverse relationship highlights the competitive occupancy between unadsorbed pyocyanin and serum protein molecules at the limited number of SERS hotspots. The 2D Raman maps (Fig. 2D) provide visual evidence of this competitive interaction, revealing an anti-correlated yet heterogeneous spatial distribution between pyocyanin and serum proteins. This heterogeneity in molecular 2D maps, despite the homogeneous distribution of the plasmonic nanogap hotspots indicated by the 2D maps of the plasmon-enhanced ERS peak from gold (Supplementary Fig. 4), underscores the dynamic molecular interactions occurring at the nanoscale. A four-parameter sigmoidal fit applied to the pyocyanin calibration curve (Fig. 2B) yielded an excellent R² value of 0.999. Based on this calibration curve, the limit of detection (LoD) and limit of quantification (LoQ) for pyocyanin was determined to be 5.6 nM and 138 nm, respectively.

A Averaged ERS-normalized SERS spectra obtained using zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes for human serum spiked with varying pyocyanin concentrations (10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁹ M), with shaded regions representing standard deviations. Control spectra of 10⁻6M pyocyanin aqueous solution and human serum without pyocyanin are provided. B Quantitative analysis of pyocyanin detection: intensity of the ERS-normalized pyocyanin peak at 545 cm⁻¹ as a function of concentration, with the error bars representing standard deviations and the red curve representing the four-parameter sigmoidal fit for calibration. C Intensity of the ERS-normalized serum protein peak at 1000 cm⁻¹, demonstrating the competitive interaction between pyocyanin and serum proteins at the SERS hotspots. * represents p-values < 0.05, indicating statistically significant difference. D 2D Raman maps corresponding to the pyocyanin concentration determined using the calibration curve and the ERS-normalized serum protein peak (1000 cm⁻¹), visually illustrating their anti-correlated spatial distribution and competitive adsorption behavior.

In situ spatiotemporal SERS analysis of P. aeruginosa biofilms

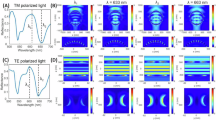

To demonstrate the capability of our zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes for continuous, real-time monitoring of biofilm dynamics, we performed spatiotemporal SERS molecular fingerprinting of P. aeruginosa lawn biofilms over 48 h. Zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes were placed on top of the lawn biofilm, prior to incubation. High-throughput SERS measurements were conducted across a 40 × 40-pixel grid, with an acquisition time of 0.1 s per pixel (Fig. 3A). We investigated three P. aeruginosa samples: wild type strain PAO1 grown on (i) LB media supplemented with 1.5% agar (LA) or (ii) on Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA), which promotes the overproduction of pyocyanin and (iii) a hyperbiofilm PAO1 mutant that overproduces the secondary messenger cyclic di-GMP (PAO1ΔwspF) grown on LA. Cyclic di-GMP is an intracellular signaling molecule in P. aeruginosa known to promote biofilm formation and enhance P. aeruginosa pathogenicity31,32. Due to the lower protein content and different protein composition and secretion dynamics in P. aeruginosa samples compared to human serum, we anticipate that the zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes can enable in situ, time-resolved monitoring of pyocyanin secretion over significantly longer durations than the 30 min observed in serum backgrounds (Supplementary Text 6).

A Schematic illustration and images of the experimental setup for biofilm monitoring. B Temporal evolution of average ERS-normalized SERS spectra over 48 h of the three P. aeruginosa samples: wild-type strain grown on LA (PAO1;LA), wild-type strain grown on PIA (PAO1;PIA), and cyclic di-GMP overproducing mutant strains grown on LA (PAO1ΔwspF;LA). C, D ERS-calibrated Raman intensities at C 545 cm–1 and D 1350 cm–1 for the three P. aeruginosa samples over 48 h, revealing distinct pyocyanin production dynamics. *** represents p values < 0.001, indicating statistically significant difference between the pyocyanin signals at 0 and 6 h. E Time-resolved 2D maps of the ERS-calibrated Raman intensities at 545 cm–1 for the three P. aeruginosa samples, visualizing the spatiotemporal evolution of pyocyanin distribution within the biofilms.

Fig. 3B presents the ERS-calibrated SERS spectra recorded between 0 and 48 h, with peak assignments detailed in Supplementary Table 2. The initial spectrum (0 h) displayed peaks at 732 and 1000 cm–1 from the background media (upplementary Fig. 5). By 6 h, peaks associated with purines (676, 732 cm–1) and tyrosine emerged (835 cm–1), indicating the secretion of bacterial metabolites. Notably, strong peaks attributed to pyocyanin were detected in all three samples within 6 h, with intensity increasing over time.

To quantitatively analyze biochemical changes during biofilm growth, we plotted the ERS-calibrated Raman intensities of pyocyanin peaks at 410, 545, 1350, and 1605 cm–1 (Fig. 3C, D, Supplementary Fig. 6). Compared to the wild type strains, the PAO1ΔwspF exhibited significantly elevated pyocyanin levels at early time points (6–24 h), followed by saturation. Previous studies have linked increased cellular cyclic di-GMP levels in hyperbiofilm PAO1ΔwspF strains to global gene expression changes, which explain our findings32. Specifically, the increase in cyclic di-GMP in the PAO1ΔwspF strains, which drives the hyperbiofilm phenotype, also leads to elevated quorum-sensing transcript levels, which regulate pyocyanin production32. Within the wild type strains, the PAO1 grown on LA showed a slower increase in pyocyanin signals, while PAO1 grown on PIA displayed a consistent pyocyanin increase over 48 h, consistent with this media promoting increased pyocyanin production33,34. Fig. 3E presents 2D Raman maps of the pyocyanin Raman band at 545 cm⁻¹ over 48 h. These maps reveal a non-uniform and dynamically evolving spatial distribution of pyocyanin, highlighting the heterogeneous structure of biofilms.

Discussion

We developed zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes that integrate L-cysteine’s antifouling capability introduced via simple click chemistry with the biocompatibility of polymeric meshes and ultrasensitive SERS performance of plasmonic nanocavity arrays. This platform allows improved SERS performance in protein-rich human serum compared to controls without L-cysteine functionalization, with an LoD of 5.6 nM for pyocyanin in undiluted human serum. This LoD falls at the lower end of the typical pyocyanin concentration range (3–25 nM) found in P. aeruginosa infected burn wounds35,36, underscoring the potential of platform for early detection of this pathogenicity factor in clinical settings. Moreover, the platform enables in situ spatiotemporal SERS monitoring of P. aeruginosa biofilms over 48 h in culture media-agar backgrounds, providing insights into biofilm growth and pyocyanin production dynamics in wild-type and hyperbiofilm mutant strains. While the biofilm growth dynamics can vary significantly across strains and environmental conditions37, the 48 h monitoring window in our study corresponds to critical stages of biofilm development characterized by key phenotypic transitions, intercellular signaling, and active metabolic secretion, providing important insights for developing treatment strategies38,39,40. Notably, we observed elevated pyocyanin levels in hyperbiofilm mutants compared to wild-type strains, underscoring the complex interplay between pyocyanin secretion, hyperbiofilm behavior and cyclic-di GMP signaling32. This in-situ spatiotemporal molecular profiling capability can open the door to correlating metabolite levels (e.g., pyocyanin) with interdependent bacterial mechanisms such as genetic mutations6, signaling7,8, and biofilm development9,10, facilitating the development of targeted therapies.

Furthermore, we observed detectable pyocyanin signals within 6 h, highlighting the potential of our approach for early P. aeruginosa infection diagnostics. Looking ahead, the platform’s potential to non-invasively and biocompatibly monitor biofilm secretion dynamics in biological tissues needs to be evaluated. This approach offers a promising avenue for real-time diagnostics and personalized treatment at complex biological interfaces, such as biofilm-infected wounds41. To fully realize this potential, future work must address long-term monitoring in physiologically relevant protein-rich environments (e.g., blood), where rapid and robust protein corona formation is likely42. This will require the development of advanced sensor regeneration strategies, such as the use of external stimuli to desorb adsorbed foulants at regular intervals, in tandem with the zwitterionic antifouling layer43. If successfully implemented, coupling this platform with artificial intelligence models44 could allow real-time correlation of spatiotemporal secretion dynamics with underlying biofilm mechanisms (e.g., signaling, mutation, or therapeutic response), enabling closed-loop, personalized and targeted biofilm management.

Methods

Fabrication of the zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes

The nanoplasmonic bio-meshes were fabricated using a soft reverse nanoimprint lithography procedure, previously developed and documented in prior works18,45, and schematically depicted in Fig. 1A. Briefly, perfluoropolyether (PFPE) (Fluorolink PFPE, Solvay, Belgium) nanopillar array templates were first replicated from a silicon master mold (pillar diameter: 120 nm, height: 300 nm, periodicity: 400 nm) using UV nanoimprint lithography. The UV nanoimprint process involved curing under 2 bar pressure for 3 min, a second curing step under vacuum for 3 min, and post-annealing at 100 °C for 45 min. A 16% (w/w) solution of polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) (molecular weight 15,000 g/mol) was spin-coated onto the PFPE nanopillar templates at 5000 rpm for 30 s. Solvent removal was achieved by baking at 180 °C for 2 min, forming PMMA nanohole arrays on the PFPE template. These PMMA nanohole arrays were then transferred onto SU-8 (SU-8 2002, Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., USA) microwell arrays (diameter: 16 m, height: 2 μm, periodicity: 64 μm) patterned on silicon wafers coated with an Omnicoat sacrificial layer (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., USA) via thermal reverse nanoimprint lithography (10 min, 2 bar, 170 °C). The SU-8 microwell arrays were fabricated through masked photolithography (MA6 Mask Aligner, SUSS MicroTec, Germany). Residual PMMA was removed using reactive ion etching (RIE-1C, Samco, Japan) with O₂ plasma (30 sccm, RF power 30 W, 50 s), thereby opening the nanoholes. Subsequently, alternating layers of Au (25 nm) and SiO₂ (8 nm and 12 nm from bottom) were deposited via electron beam evaporation (PVD250, Kurt J. Lesker, USA) through the PMMA nanohole mask. A 0.7 nm titanium adhesion layer was inserted between the Au and SiO₂ layers, and a 1 nm chromium adhesion layer was deposited between the Au layer and the substrate. Following deposition, the PMMA mask was dissolved in anisole at 70 °C. Residual anisole and PMMA were removed by a second round of reactive ion etching (O₂ plasma, 30 sccm, RF power 30 W), followed by rinsing with ethanol and DI water. The dielectric nanogaps were subsequently opened by immersion in buffered oxide etchant (BOE 10:1, Transene Inc., USA) for 10 s at room temperature without agitation.

To generate the zwitterionic surface layer, the substrates were incubated in a 100 μM aqueous solution of L-cysteine (Sigma Aldrich, USA) for 1 h, then sequentially rinsed with ethanol and deionized water to remove unbound molecules. To release the nanoplasmonic bio-meshes, the devices were immersed in Remover PG (Kayaku Advanced Materials Inc., USA) for 15 min at 70 °C. The released meshes were rinsed three times with deionized water using a Pasteur pipette to remove residual Remover PG, sterilized in ethanol for 30 min, and then transferred to target substrates using sterilized polyethylene terephthalate sheets as the transfer medium.

Extinction Measurements

A UV–vis–NIR spectrophotometer (Cary 5000, Agilent, USA) was used to measure the extinction spectra.

SERS Measurements

For SERS measurements, a confocal Raman microscope (alpha 300RSA + , WItec, Germany) equipped with a 785 nm diode laser (Xtra II, Toptica, Germany) was used. The backscattered photons were detected with a spectrometer (UHTS300, WItec, Germany) equipped with a CCD camera (DU401A, Oxford Instruments, UK). Signals were collected using a 300 grooves/mm grating via a 20× objective lens with 1 mW power measured using an optical power meter (Thorlabs, Inc.).

Data analysis

After the signal acquisition, baseline correction, cosmic ray removal, and spectral filtering via Savitsky Golay filtering (window size = 5, polynomial order = 3) were performed using the Project v4.1 Software (WITec, Germany). The SERS data was normalized using the plasmonic ERS signals, reflected by the pseudo peak at 77 cm–1, as the internal standards. Plasmon-enhanced ERS signals from metal can serve as an internal standard for spatial and temporal calibration of molecular Raman scattering signals from analyte molecules at the same hotspots, enabling rigorous quantitative SERS analysis29,46. To statistically assess differences between measurements, a Student’s t test was performed using MATLAB, with the resulting p-value indicating the significance of the observed differences. Independent two-sample t tests were used in Figs. 1 and 2 to compare measurements across different sample groups, while paired t tests were applied in Fig. 3 to compare Raman band intensities from the same bacterial samples at different time points.

Rhodamine 6 G (R6G) detection in blood serum

Both L-cysteine functionalized and bare SERS devices, prior to release from the silicon substrate, were attached to the bottom of 35 mm petri dishes using Norland Optical Adhesive (NOA83). We then sequentially exposed both devices to three solutions for 10 min each: (1) undiluted human serum (Sigma Aldrich, USA), (2) deionized water, and (3) human serum spiked with 10 μM R6G (Sigma Aldrich, USA). R6G solution was prepared in deionized water before spiking into human serum. Throughout the 30 min period, the devices remained under the microscope in the same position. First, 2 ml of human serum was added, and SERS measurements were taken at t = 0, 5, and 9 min. At t = 10 min, the serum was removed, the device was rinsed three times with deionized water, and replaced with 2 ml of fresh deionized water. SERS measurements were taken at t = 15 min. The water was then replaced with 2 ml of serum spiked with 10 μM R6G, and measurements were taken at t = 20, 25, and 29 min. Each SERS measurement covered 50 pixels with a 1 s integration time (total scanning time = 50 s).

Pyocyanin detection in blood serum

L-cysteine functionalized SERS devices, before release from the silicon substrate, were attached to the bottom of 35 mm petri dishes using Norland Optical Adhesive (NOA83). The devices were first incubated in 2 ml of undiluted human serum for 10 min. Following this, the serum was replaced with 2 ml of human serum spiked with varying concentrations of pyocyanin (10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁹ M). SERS measurements were then conducted, covering 25 pixels with a 1 s integration time per pixel.

LoD quantification

A four-parameter sigmoidal fit was applied to generate the calibration curve using the following equation: \(y=d+\frac{a-d}{1+{(\frac{x}{c})}^{b}}\), where x = -log10(concentration of pyocyanin in M) and y=normalized Raman peak intensity. The fitted parameters for the two Raman peaks were:

545 cm-1 Raman peak: a = 0.0138, b = −9.5267, c = 5.1581, and d = 0.3051

1350 cm-1 Raman peak: a = 0.0029, b = −13.0421, c = 5.4980, and d = 0.1209

The LoD and the LoQ were calculated using the 545 cm-1 Raman peak. Meancontrol + 3 SDcontrol and Meancontrol + 10 SDcontrol were used as the thresholds for the LoD and LoQ, respectively. Meancontrol and SDcontrol are the average intensity and standard deviation, respectively, of the 545 cm-1 peak in human serum without pyocyanin.

Growth of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lawn biofilms

Mid-log cultures of P. aeruginosa PAO147 and PAO1ΔwspF48 were normalized to OD600 0.5. Cell pellet was resuspended in a equal volume of PBS, and a 100 μL aliquot spread plated onto solidified media. PAO1 was grown on both LA (Luria-Bertani broth (pH = 7) solidified with 1.5% agar) and PIA (Pseudomonas isolation agar (pH = 7) solidified with 1.5% agar). PAO1ΔwspF was grown on LA. Once the bacterial culture had dried, the sterile zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-mesh was placed on top. Lawn biofilms were incubated at 37 °C. Three biological replicates were analyzed.

Spatiotemporal SERS analysis of P. aeruginosa biofilms

SERS measurements were performed via a 20× objective lens with 1 mW power and 0.1 s integration time over a 120 um* 120 um region containing 1600 pixels at various times. Between SERS measurements, the plate was stored at 37 °C.

Data Availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text of the paper and its supplementary information files. Additional datasets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Su, Y. et al. Biofilms: formation, research models, potential targets, and methods for prevention and treatment. Adv. Sci. 9, e2203291 (2022).

Cámara, M. et al. Economic significance of biofilms: a multidisciplinary and cross-sectoral challenge. npj Biofilms Microbiomes 8, 42 (2022).

Ali, A. et al. Microbial biofilms: applications, clinical consequences, and alternative therapies. Microorganisms 11, 1934 (2023).

Sen, C. K. Human wounds and its burden: an updated compendium of estimates. Adv. Wound Care 8, 39–48 (2019).

Saccomano, S. C., Jewell, M. P. & Cash, K. J. A review of chemosensors and biosensors for monitoring biofilm dynamics. Sens. Actuators Rep. 3, 100043 (2021).

She, P. et al. PA2146 gene knockout is associated with Pseudomonas aeruginosa pathogenicity in macrophage and host immune response. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 559803 (2020).

Wang, M. et al. Cladodionen is a potential quorum-sensing inhibitor against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mar. Drugs 18, 205 (2020).

Nadal Jimenez, P. et al. The multiple signaling systems regulating virulence in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 76, 46–65 (2012).

Das, T., Kutty, S. K., Kumar, N. & Manefield, M. Pyocyanin facilitates extracellular DNA binding to Pseudomonas aeruginosa influencing cell surface properties and aggregation. PloS One 8, e58299 (2013).

O’Loughlin, C. T. et al. A quorum-sensing inhibitor blocks Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 17981–17986 (2013).

Bisht, K. & Wakeman, C. A. Discovery and therapeutic targeting of differentiated biofilm subpopulations. Front. Microbiol. 10, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01908 (2019).

Jo, J., Price-Whelan, A. & Dietrich, L. E. Gradients and consequences of heterogeneity in biofilms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 20, 593–607 (2022).

Koo, H. & Yamada, K. M. Dynamic cell–matrix interactions modulate microbial biofilm and tissue 3D microenvironments. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 42, 102–112 (2016).

Magana, M. et al. Options and limitations in clinical investigation of bacterial biofilms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, 00084–00016 (2018).

Funari, R. & Shen, A. Q. Detection and characterization of bacterial biofilms and biofilm-based sensors. ACS Sens. 7, 347–357 (2022).

Langer, J. et al. Present and future of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. ACS Nano 14, 28–117 (2019).

Garg, A. et al. Microporous multiresonant plasmonic meshes by hierarchical micro–nanoimprinting for bio-interfaced SERS imaging and nonlinear nano-optics. Small 18, 2106887 (2022).

Garg, A., Mejia, E., Nam, W., Vikesland, P. & Zhou, W. Biomimetic transparent nanoplasmonic meshes by reverse-nanoimprinting for bio-interfaced spatiotemporal multimodal SERS bioanalysis. Small 18, 2204517 (2022).

Garg, A., Nam, W., Wang, W., Vikesland, P. & Zhou, W. In situ spatiotemporal SERS measurements and multivariate analysis of virally infected bacterial biofilms using nanolaminated plasmonic crystals. ACS Sens. 8, 1132–1142 (2023).

Ivleva, N. P. et al. Label-free in situ SERS imaging of biofilms. J. Phys. Chem. B 114, 10184–10194 (2010).

Bodelón, G. et al. Detection and imaging of quorum sensing in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm communities by surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering. Nat. Mater. 15, 1203–1211 (2016).

Lin, P., Chuang, T.-L., Chen, P. Z., Lin, C.-W. & Gu, F. X. Low-fouling characteristics of ultrathin zwitterionic cysteine SAMs. Langmuir 35, 1756–1767 (2019).

Lin, P., Ding, L., Lin, C.-W. & Gu, F. Nonfouling property of zwitterionic cysteine surface. Langmuir 30, 6497–6507 (2014).

Zhou, T. et al. Syringe-injectable mesh electronics integrate seamlessly with minimal chronic immune response in the brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114, 5894–5899 (2017).

Nam, W. et al. Refractive-index-insensitive nanolaminated SERS substrates for label-free Raman profiling and classification of living cancer cells. Nano Lett. 19, 7273–7281 (2019).

Chen, S., Li, L., Zhao, C. & Zheng, J. Surface hydration: principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polymer 51, 5283–5293 (2010).

Chen, S., Zheng, J., Li, L. & Jiang, S. Strong resistance of phosphorylcholine self-assembled monolayers to protein adsorption: insights into nonfouling properties of zwitterionic materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14473–14478 (2005).

Franco, V. G., Rodríguez, S. J., Calaza, F. C., Passeggi, M. C. G. & Ruano, G. D. Novel mixed self-assembled monolayers of L-cysteine and methanol on gold surfaces under ambient conditions. Nanoscale 16, 15366–15380 (2024).

Nam, W. et al. Plasmonic electronic Raman scattering as internal standard for spatial and temporal calibration in quantitative surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 9543–9551 (2020).

Garg, A., Nam, W. & Zhou, W. Reusable surface-enhanced raman spectroscopy membranes and textiles via template-assisted self-assembly and micro/nanoimprinting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 56290–56299 (2020).

Kuchma, S. L. et al. BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8165–8178 (2007).

Hickman, J. W., Tifrea, D. F. & Harwood, C. S. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 14422–14427 (2005).

King, E. O., Ward, M. K. & Raney, D. E. Two simple media for the demonstration of pyocyanin and fluorescin. J. Lab. Clin. Med. 44, 301–307 (1954).

Brown, V. & Lowbury, E. Use of an improved cetrimide agar medium and other culture methods for Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Clin. Pathol. 18, 752–756 (1965).

Muller, M., Li, Z. & Maitz, P. K. Pseudomonas pyocyanin inhibits wound repair by inducing premature cellular senescence: role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Burns 35, 500–508 (2009).

Hall, S. et al. Cellular effects of pyocyanin, a secreted virulence factor of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Toxins 8, 236 (2016).

Žiemytė, M. et al. Real-time monitoring of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm growth dynamics and persister cells’ eradication. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 10, 2062–2075 (2021).

Stoodley, P., Sauer, K., Davies, D. G. & Costerton, J. W. Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56, 187–209 (2002).

Davies, D. G. et al. The involvement of cell-to-cell signals in the development of a bacterial biofilm. Science 280, 295–298 (1998).

Flemming, H.-C. & Wingender, J. The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633 (2010).

James, G. A. et al. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regener.16, 37–44 (2008).

Fernández-Iglesias, N. & Bettmer, J. Complementary mass spectrometric techniques for the quantification of the protein corona: a case study on gold nanoparticles and human serum proteins. Nanoscale 7, 14324–14331 (2015).

Sibug-Torres, S. M. et al. In situ electrochemical regeneration of nanogap hotspots for continuously reusable ultrathin SERS sensors. Nat. Commun. 15, 2022 (2024).

Bi, X. et al. Artificial intelligence-powered surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for biomedical applications. Anal. Chem. 97, 6826–6846 (2025).

Zhao, Y. et al. Voltage modulation of nanoplasmonic metal luminescence from nano-optoelectrodes in electrolytes. ACS Nano 17, 8634–8645 (2023).

Nam, W. et al. Plasmonically calibrated label-free surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for improved multivariate analysis of living cells in cancer subtyping and drug testing. Anal. Chem. 93, 4601–4610 (2021).

Holloway, B. Genetic recombination in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology 13, 572–581 (1955).

Harrison, J. J. et al. Elevated exopolysaccharide levels in Pseudomonas aeruginosa flagellar mutants have implications for biofilm growth and chronic infections. PLoS Genet. 16, e1008848 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation grants CBET-2231807 and DMR 2139317, Air Force Office of Scientific Research grant FA9550-23-1-0282, and Commonwealth Health Research Board grant 208-09-24. The funder played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. and W.Z. conceived the idea, with W.Z. supervising the project. A.G. fabricated and characterized the device, designed and performed SERS experiments, and conducted data analysis. Z.Z. assisted with SERS measurements, while E.S.G. cultured bacterial biofilms. E.S.G. and P.V. contributed comments on the manuscript. A.G. and W.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Garg, A., Zong, Z., Vikesland, P. et al. Zwitterionic nanoplasmonic bio-meshes for in situ spatiotemporal SERS monitoring of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. npj Biosensing 2, 30 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00052-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00052-z