Abstract

This perspective discusses the future role of all-optical label-free single-molecule sensing. After summarizing the core working principles of the different detection modalities we discuss future research directions in terms of technology development and applications. In terms of future technologies we address research directions in the areas of multi-parametric and interaction free sensors, integration and miniaturization, and advanced data analysis. We further describe potential applications towards probing of protein interactions, DNA and protein sequencing, and molecular diagnostics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biomolecules such as proteins and nucleic acids play essential roles in various biological processes, including metabolism, genetic replication, molecular transport, and the maintenance of cellular and tissue structure. Their functional mechanisms are intricately linked to their chemical composition and structural characteristics, such as sequence and three-dimensional conformation. Moreover, the concentrations of these biomolecules often fluctuate in pathological conditions, offering valuable biomarkers for disease diagnosis when accurately quantified. Consequently, the detection and analysis of biomolecules represent a critical area of scientific research, with biomolecular sensors serving as indispensable tools for elucidating molecular function and enabling clinical diagnostics.

Optical sensors play a central role in the field, which started in 1941 when Albert Coons developed methods to fluorescently label antibodies and detect them by immunofluorescence1. This discovery revolutionized the field of biomolecular detection because it led to the development of Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA) in 19712,3. ELISA in its current form sensitively detects nearly any protein with unrivaled sensitivity because the signal is amplified by fluorescently labeled antibodies or enzymes. Similarly, a new method was developed for the highly sensitive detection of nucleic acids which was termed Polymerase Chain Reaction4 and has since become the gold standard for nucleic acid detection.

Around the same time, methods for biomolecular detection were developed that do not require fluorescent (or other) labels. In the late sixties, optical excitation of surface plasmon resonances (SPR) by means of attenuated total reflection was demonstrated by Kretschmann and Raether5 and Otto6. The use of such SPR for biomolecular detection was demonstrated in 1983 by Liedberg et al.7. Local changes in refractive index in the vicinity of a gold film induce a resonance shift, a sensing mechanism that relies solely on the optical density of the biomolecule. Combined with fluidics, SPR sensors enable the quantification of binding kinetics and equilibria, and have become a workhorse technology.

The above technologies are all so-called ensemble-averaged methods: the signal is accumulated across many molecules, in some cases up to a trillion. An increasing number of studies shed light on the importance of monitoring individual biomolecules, a notion that was further amplified by the first detection of the optical absorption by a single molecule at cryogenic temperatures in 1989 by Moerner and Kador8. 1 year later, Orrit and Bernard detected a fluorescence signal from a single molecule, also at cryogenic temperatures9. Yet a few years later, single-molecule fluorescence was detected at room temperature10, thereby opening the window to biological applications. Since then, fluorescence has been the main tool for single-molecule detection and has become indispensable in the fields of life- and materials science.

Although widely employed, single-molecule fluorescence is fundamentally restricted to species that exhibit a sizeable quantum yield (typically > 0.1). Detection of weakly and non-emitting species is thus often done by fluorescently labeling the molecule of interest. However, such labeling is not always possible (e.g., in applications like biosensing) and not always desired (e.g., because fluorescence labeling perturbs the molecule under study)11. Starting in the 2010s, this has sparked major efforts to achieve so-called “label-free” sensors with single-molecule sensitivity.

Label-free single-molecule detection has been demonstrated using two broad classes of sensors: resonator-based sensors (plasmonic and photonic) and interferometry-based sensors (interferometric scattering). Several excellent reviews have been published in the past years that provide an overview of these approaches and highlighted the technology behind these detection methods12,13,14,15,16. In this perspective, we take a different approach and will only shortly highlight the different detection methods and thereafter focus on future perspectives. We discuss the future perspectives along two directions: the further development of the technology to increase its capabilities, and the integration of the technology in relevant application areas.

Before continuing, it is pertinent to wonder which advantages single-molecule detection brings over ensemble-averaged approaches. The advantages are threefold: first, single-molecule sensors provide digital signals, enabling the direct counting of molecules and/or interactions. This has particular advantages in diagnostics where low concentrations of biomarker need to be quantified, sometimes against slowly varying background signals. Second, it enables the detection of molecular processes that are not synchronized in time. Examples are conformational dynamics, equilibrium interaction kinetics, biomolecular folding, and the vast majority of complex biomolecular mechanisms. Third, it enables the analysis of heterogeneity within a seemingly homogeneous sample because the characteristics of each single-molecule event are directly resolved (e.g., the signal amplitude or the state-lifetime). This enables the distinction between different populations of biomolecules caused by, e.g., sequence or conformational heterogeneity.

Sensing modalities

Several technologies have been reported in the past 15 years that achieve all-optical label-free single-molecule detection. We restrict ourselves to technologies that resolve local changes in refractive index at ambient temperature: these are the most generic single-molecule detection methods because they do not rely on a strong absorption17,18, fluorescence10, or Raman scattering19,20 of the molecule. We also restrict ourselves to describing only their main features to give the reader a flavor of the working principles, allowing us to focus on the future perspectives of the techniques. We refer the reader to two recent reviews for an exhaustive overview of the state-of-the-art15,21.

Resonator-based sensing

Plasmonics

In the early 2000s, the field of label-free plasmon sensing focused on the optical detection of the plasmon wavelength shift of single biofunctionalized metallic particles for biosensing22. Advances in wet-chemical synthesis then lead to a major step in sensitivity because the plasmon resonance of nanorods and bipyramids23 is narrower and exhibits higher field enhancements due to sharper geometrical features24. True single-molecule resolution without statistical averaging was demonstrated in 2012 simultaneously by Ament et al.25 and by Zijlstra et al.26. Initial implementations used single-particle microscopy to probe the plasmon wavelength shift of a single particle at a time, but in 2015, the use of wide-field microscopy enabled the interrogation of hundreds of sensors in parallel27.

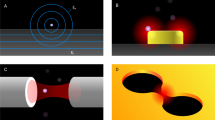

In a different approach, propagating plasmon resonances on metallic films are exploited for single-molecule detection. Such platforms do not monitor resonance shifts of plasmonic nanostructures, but rather exploit the strong evanescent field associated with the propagating plasmon on a metallic film that polarizes a nearby molecule28. Early implementations are coined SPR imaging, wherein the reflected intensity of a metallic film is monitored on a camera29, see Fig. 1b. This reveals nanoscale scattering objects on the film as a perturbation of the propagating plasmon and was first employed to detect single viruses30 and later single proteins31. It is worth noting that in these plasmonic microscope sensors the single-molecule sensitivity arises from both SPR and interferometric mechanisms which will be discussed below. In a different approach, plasmon-enhanced fluorescence in the UV has been demonstrated for the detection of single proteins by their autofluorescence that is induced by tryptophan residues32.

Approaches based on a, b optical microscopy of single plasmonic nanoparticles and metallic films, c, d optical transmission probing of nanometric apertures in a metal film, e, f optical spectroscopy of whispering gallery modes and Fabry Perot resonances in dielectric microcavities, g, h interferometric scattering microscopy, and i, j interferometric nanofluidic scattering microscopy. a Reproduced with permission from27. Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society. b Adapted with permission from28,165. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society and 2018 National Academy of Sciences. e Adapted with permission from75. Copyright 2021 The Authors. f Adapted withpermission from80. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. h Adapted with permission from84,90,93. Copyright 2004 American Physical Society. Copyright 2014 Springer Nature. “This is an unofficial adaptation of an article that appeared in an ACS publication. ACS has not endorsed the content of this adaptation or the context of its use.” j, k Reproduced with permission from96. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature.

The above plasmonic approaches have been applied for the detection IgG, IgM, and IgA, which are relevant biomarkers for diagnostic applications. The strongly confined field associated with plasmon resonances has also enabled the tracking of translational and rotational diffusion of single particles and single molecules through the near-field of the nanoparticle on nanosecond timescales33,34,35. Probing of conformational dynamics has also been demonstrated using e.g., nanoparticle dimers where the molecule of interest is sandwiched between two particles36,37,38, a nanoparticle-on-film sensor where the molecule is sandwiched between a planar film and a particle39,40, or for a tethered molecule above a metallic film31.

Nano-apertures

In an alternative approach, single proteins can be trapped and detected by laser light focused on a double nanohole aperture in a metal film41, see Fig. 1c. Strong electric field gradients in the aperture region induce protein trapping in a range of nanoaperture shapes, e.g., coaxial42,43 or bowtie44 geometries. The transmission of the aperture is modulated upon biomolecular trapping, which can be exploited to detect short single stranded DNA45, proteins or peptides46. The Brownian motion of the trapped molecule induces signal fluctuations that allow for characterizing hydrodynamic properties of the protein47. In addition, the amplitude of the scattering signal fluctuations scales linearly with the protein mass and is less dependent on the hydrodynamic properties.

The trapping with nanoapertures has been attributed to the self-induced back-action effect, where the presence of a nanoparticle shifts the resonance of the aperture to increase the local electromagnetic field intensity and thereby enhance the trapping efficiency48,49. There is also an interferometric component to the sensing signal (like interference scattering in Section “Interference-based sensing”), which enhances the ability to detect proteins even before trapping50. An important feature of nanoaperture optical tweezers is that the gold film is a good thermal conductor that limits typical temperature increases to a Kelvin per milliwatt of laser power51,52,53.

As such, nanoaperture optical tweezers resolve the dynamics of single proteins for hours54. Conformational dynamics of proteins and binding events give rise to changes in the detected laser signal55,56, which has been quantified theoretically through changes in the polarizability of the protein57 and experimentally by the observation of the disassembly of molecular complexes58,59. Nanoaperture optical tweezers can also be combined with Raman systems to get information about the trapped nanoparticle60,61,62,63, or with nanopores for simultaneous optical and electrical signal characterization of biomolecules and their interactions52,64,65,66.

Microcavities

Optical microcavities of different shapes (Fig. 1e) confine electromagnetic waves through internal reflection, thereby generating resonance conditions at specific frequencies. A notable example, the whispering gallery mode (WGM) microcavity, is named after an acoustic phenomenon described by Lord Rayleigh in the 19th century when he heard whispers travelling around the dome of London’s St Paul’s Cathedral. In one implementation, glass microspheres of ~100 µm in diameter are used because they exhibit quality factors as high as ~1011 67 thereby enabling sensitive probing of resonance shifts due to local refractive index changes68,69 for biological and physical sensing70.

A further improvement in sensitivity can be gained by modifying the cavity with plasmonic nanostructures, such as gold nanorods. Such optoplasmonic approaches enhance the sensitivity due to further field confinement at the nanorod’s tips (similar to the plasmon sensing modality described above)71. These platforms have enabled label-free detection of a variety of biomolecules such as proteins, oligonucleotides and small molecules72,73,74. In addition, the activity of enzymes and conformational dynamics75 can be probed by exploiting the motion of the biomolecule in the strong field gradient near the nanoparticle’s surface. Recently, mode-splitting76 and photoacoustic effects have been exploited to detect single nanoparticles and cells using WGM sensors77.

A promising emerging optical microcavity for single-molecule sensing is the Fabry–Pérot (FP) cavity, formed by the ends of two optical fibers that face each other to create a water-filled open-access78 sensing cavity (Fig. 1f). When higher optical powers are coupled, the thermo-optical effect induced by water absorption provides single-molecule sensitivity down to single small peptides. The signal generation mechanism is highly non-linear: the added polarizability of a non-absorbing single molecule slightly shifts the (thermally locked) cavity which triggers a cooling cascade. This cascade causes a rapid shift of the cavity resonance79 and results in large signal amplitudes even for small molecules like peptides80. Unlike the WGM resonators discussed above, this scheme does not require biofunctionalization of the sensor surface but rather detects properties (e.g., size) of freely diffusing molecules.

Interference-based sensing

The above detection modalities exploit resonances and their shifts for biomolecular detection. Here, we describe single-molecule sensing strategies that rather use interference for signal amplification.

Interferometric scattering microscopy

In microscopy-based detection the challenge to achieve (label-free) single-molecule sensitivity arises from detecting the small changes to an image resulting from the presence of the molecule. One means to achieve this is to take advantage of interference between (the very weak) light intensity that is scattered from the molecule, and a reference beam. The interference signal is maximized if scattered and reference light fields are adjusted such that they interfere destructively. This approach has been originally popularized in the form of phase contrast microscopy81, and further refined in various implementations such as reflection imaging82,83.

In terms of raw sensitivity, interference microscopy entered the nanoscale with the advent of nanoscience, demonstrating interference-based detection of 5 nm metallic nanoparticles84,85,86. The work by Lindfors et al. in particular launched what is now known as interferometric scattering microscopy (iSCAT) that has been used for the detection, imaging and spectroscopic investigation of nanoparticles16. In iSCAT, the analyte is usually detected in reflection at a glass water interface that provides the reference light field by its reflection. Importantly, static imaging background87 can be mitigated by using atomically flat surfaces88 or by using background subtraction to achieve near shot noise limited detection89,90.

Simultaneously with others18,91, this approach led to the first extinction-based imaging and detection of single molecules at room temperature92. Further improvements then demonstrated label-free detection, imaging, localization and tracking of single unlabeled proteins93 down to 60 kDa89. The application of machine learning to iSCAT has recently reported detection of polypeptides as small as 9 kDa94.

Nanofluidic scattering microscopy

Nanofluidics enables control of fluids at length scales <100 nm95 by utilizing tiny channels or “tunnels” embedded into a solid-state substrate (often Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) or SiO2) using nanofabrication techniques (Fig. 1i). Nanofluidic scattering microscopy (NSM) exploits the interference between light scattered by the nanofluidic channel itself, and a biomolecule inside the channel. The optical contrast is proportional to the molecular weight of the imaged molecule (Fig. 1j), which can be determined from a differential image as described in the section on iSCAT above. The diffusive motion of an object, on the other hand, can be tracked along the nanofluidic channel to obtain hydrodynamic properties (Fig. 1k) of single biomolecules and larger biological nanoparticles such as extracellular vesicles96.

In terms of size and mass resolution, the integrated optical contrast of an imaged molecule or nano-object is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area, A, of the nanochannel96. This means that smaller channels, in principle, can resolve smaller objects or molecules. However, since smaller nanochannels scatter less light and thus require higher laser power there is a tradeoff between nanochannel size and required optical power. To date, NSM has demonstrated the label-free detection and analysis of single proteins down to 66 kDa.

The integrated optical contrast of a nanofluidic channel also depends on the refractive index of the solution inside the nanochannel97. This enables measurements of the absolute solute concentration in a liquid, or the conversion of reactant molecules to a product by a single catalyst nanoparticle localized inside the channel97,98. Finally, it is possible to add a spectroscopic dimension to NSM by measuring the spectrally resolved light scattering intensity to determine the molar extinction coefficient of a solute99. Reliable and easy to use surface passivation schemes have been reported, such as the supported lipid bilayer used by Spačková et al.96 or alternative solutions100 that render the method compatible with biological species with varying physicochemical properties.

Future perspectives: technology development

Multi-parametric sensing

While raw detection sensitivity is a pre-requirement for sensing applications, especially at the single-molecule level, significant additional information or control is required to convert detection into a more broadly useful measure. If a biomolecular sample has been optimally purified and is perfectly homogeneous, then single-molecule detection does not provide additional information over what is already known from the bulk. However, when the sample is heterogeneous—be that in terms of mass, assembly, or conformation—single-molecule information can help.

An important source of heterogeneity is mass: as a result mass spectrometry has become one of the most used bioanalytical technologies. Optical approaches have recently been introduced in the form of mass photometry (MP)101. MP uses the linear relationship between the optical signal and the mass of the object to not only detect, but also “weigh” the object. Recent developments96 have added information on additional properties, such as size, and conformation, enabled by detection in solution, rather than on a glass surface.

Another important source of heterogeneity is caused by assembly, which is at the basis of almost all cellular function and regulation. Most proteins are oligomeric and held together by non-covalent interactions, which implies that they will form a heterogeneous mixture of different oligomers dictated by thermodynamics. Characterizing the oligomeric state is thus of immense value, in particular when that is done as a function of concentration, environment (pH, temperature, ionic strength) or the presence of substrates and interaction partners102.

Additionally, there is significant potential in detecting conformational changes that appear heterogeneously even in purified samples. Single-molecule measurements are ideal in this context because they remove the need for synchronization and can resolve heterogeneity naturally103. Label-free detection of conformational changes, however, requires a higher optical power density to achieve sufficient signal-to-noise ratio to detect minute changes in polarizability of the protein56,57. Having said that, exploiting near-field gradients104 or interferometric detection schemes could alleviate this105.

Even more information could be obtained by using correlative detection technologies that integrate complementary optical techniques106. Since the 1980s, various non-destructive optical tools such as optical tweezers107, surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy108, surface enhanced infrared absorption109, and circular dichroism spectroscopy110 have been developed to probe mechanical, optical, and structural properties of biomolecules. Combining different detection modalities will provide richer information and may enable the correlation between e.g., chemical structure and conformation, or mechanical properties and interaction kinetics as shown in Fig. 2a. Combining these technologies is an exciting challenge: some have not yet reached single-molecule sensitivity, while their integration requires advances in optics, protein engineering, and data analysis to extract truly meaningful information.

Interaction-free analysis

Nonlinear FP cavities, plasmonic sensor platforms, and NSM offer exciting prospects for interaction-free single-molecule detection, mass photometry and protein dynamics (see Fig. 2b). For example, in high-finesse FP microcavities with a very small mode volume, freely diffusing molecules cause

detectable resonance shifts as discussed above. Unlike other single-molecule sensing approaches, FP sensing does not require surfaces for signal enhancement or immobilization, allowing the detection and quantification of molecular properties in free solution. Nonlinear FP sensing has already shown distinct responses to different molecular weights and conformations of single proteins and DNA, with a mass limit and measurement bandwidth approaching 1 kDa and 500 kHz, respectively80. This allows extraction of meaningful molecular information, including size and diffusional properties, from mixtures of multiple molecular species without being perturbed by surfaces.

Towards micro- and nanosecond sensing of freely diffusing species, another exciting direction is the use of near-field enhancement by plasmonic nanoparticles and interferometric measurements33,35. This technique enables detection of rapid LSPR resonance shifts from scattering signals induced by freely diffusing molecules passing through the plasmonic near fields. These measurements have enabled single-molecule detection in nanoseconds, which has already been used to resolve the diffusion of larger proteins35. With purpose-tailored plasmonic nanostructures to further enhance and confine near-field, it is envisioned that fast changes in protein structures could be resolved.

There is much potential to further advance interaction-free sensing technologies. Experimental advancements, such as further suppression of external noise sources, are expected to lead to marked improvements, including detection of even smaller molecules. A combination with quantitative modeling taking into account molecular polarizabilities57 may enable selectively gathering information from different diffusional populations79. In addition, it may enable the extraction of more complex processes such as conformation, interactions, and enzymatic cleavage that are all expected to affect the diffusion properties of biomolecules.

Integration and miniaturization

The Covid-19 pandemic has underscored the urgent need for rapid and accurate diagnostic technologies, prompting governments and healthcare sectors to prioritize innovation in biomolecular detection. As of 2025, commercial single-molecule sensors span both fluorescence-based and label-free technologies, enabling high-resolution analysis of biomolecular interactions. Fluorescence-based systems from companies like LUMICKS111, Luminex112, and Pacific Biosciences113 allow real-time visualization and sequencing at the single-molecule level by integrating optical and biochemical workflows. In contrast, fluorescence-free platforms from Envue Technologies114, Oxford Nanopore Technologies115, Refeyn116, and Helia Biomonitoring117 detect molecules without fluorescent tags, using techniques such as light scattering, particle tracking, and NSM.

These table-top solutions are largely geared towards research and development applications. Nevertheless, a growing demand for precision treatment has accelerated the development of even smaller (portable), user-friendly, and point-of-care based devices118, see Fig. 2c. Portable microscopes, including those integrated with smartphone cameras, have shown potential in biosensing applications but require further improvements in sensitivity for use at the single-molecule level119. Signal-enhancement techniques provided by plasmon resonances have demonstrated promising results in miniaturized devices120,121 and have even pushed the detection limit to the single-molecule level122.

Looking ahead, the integration of photonic circuits could revolutionize biosensor miniaturization, enabling millimeter-scale devices for continuous health monitoring. These circuits can integrate excitation sources, detectors, and sensors onto a single chip, paving the way for smart pills, wearables, and implantable devices123. The fusion of semiconductor and optical sensor technologies is crucial for this progress. Additionally, incorporating artificial intelligence and machine learning into diagnostic systems can facilitate real-time decision-making and personalized treatments, as seen in theranostic applications like automated insulin delivery in glucose sensors124.

For biomedical research and development applications, it is also crucial to integrate single-molecule sensing technologies into existing laboratory workflows and environments. To this end, minimizing the level of expertise required for operation by non-expert users is essential. This can be achieved through several approaches, such as improving sensor designs for easy installation and replacement without optical alignment, developing low-cost, replaceable sensor materials and platforms that maintain single-molecule sensitivity and incorporating automated systems for sample preparation and streamlined data collection. These advancements will not only enhance instrument operability and data reproducibility but also enable broader adoption of single-molecule analysis in biomedical research.

Data analysis

Label-free single-molecule sensing has made impressive progress on the hardware and sample side in terms of evermore sophisticated microscopes and micro- or nanostructured surfaces being used. At the same time, it is also clear that key common underlying challenges in this field, irrespective of the used sensing method, are (i) to extract tiny signals from noise in the low S/N regime, (ii) to extract a specific component from a complex signal, e.g., if multiple analytes are present in a complex mixture sample and (iii) to enable real time analysis. Data analysis is a cornerstone of label-free single-molecule sensing already today and will be even more so in the future as the field further advances and investigated samples will become more complex, see Fig. 2d.

The first two challenges identified above are well-suited for deep learning algorithms. Neural networks already enabled cross-modality transformations in optical microscopy to e.g., transform simple bright-field (transmission) images to fluorescence images using so-called virtual staining125. In the field of label-free sensing neural networks have been employed for the analysis of iSCAT images to push the limit of detection to polypeptides as small as 9 kDa94, while a related approach enabled the accurate quantification of hydrodynamic radius and molecular weight in NSM down to 66 kDa96 and later down to 5.8 kDa126. In addition, the use of machine learning for data analysis can alleviate the requirements on the optical designs and enable lower-cost sensors127. These advancements have been inspired by the breathtaking development of computer vision algorithms and their application in optical microscopy128,129. It is therefore both desirable and expected that tailored machine-learning algorithms will play a key role in pushing the limits of label-free single-molecule sensing on all fronts. One particularly powerful approach would be to enable label-free single-molecule sensing in complex samples, which may encompass mixtures of many different analytes and/or high analyte concentrations with an overwhelming background.

Furthermore, it is clear that machine learning approaches offer the tantalizing possibility to distinguish the molecular components of complex sample mixtures with single-molecule resolution and quantitatively characterize the single-molecular properties of said components. Training algorithms to classify single molecules, determine protein aggregation states, and more. This may enable the real-time analysis data while simultaneously rejecting background signals. One step further, one can envision the use of digital twins alongside AI to interpret real-time sensing data. This approach leverages extensive information on static structures, molecular dynamics simulations and may provide the ability to predict and interpret sensor signals.

Detection of multiple single-molecules

For single-molecule sensing, the capability to detect and analyze multiple molecules simultaneously is crucial. For example, dynamic interactions among different molecular species underpin many biological processes, and single-molecule technologies hold great promise for unraveling these mechanisms with molecular precision.

In wide-field approaches, simultaneous tracking of multiple molecules can be achieved relatively straightforwardly, though typically with a trade-off between field of view and spatial resolution27,130. Achieving high-throughput detection without compromising single-molecule sensitivity will require advanced image processing and rapid machine-learning–based classification. Indeed, nanopore sensing and flow cytometry have already demonstrated high accuracy and throughput through the use of such methods131,132, and similar advances are anticipated for wide-field single-molecule imaging. For WGM and plasmonic sensors, multiplexed detection could be realized using frequency combs133, where each spectral line exhibits a distinct evanescent decay length and polarization, enabling 100 s of parallel sensing channels. Another promising strategy is to exploit spatial variations in field intensity across different cavity modes, as demonstrated in WGM sensing134. In NSM, throughput may be further enhanced by employing multiple nanochannels in parallel. Ongoing progress in multiplexed sensing strategies is poised to expand the throughput, precision, and versatility of single-molecule sensing technologies.

Future perspective: applications

Protein interaction pathways

Single-molecule sensing is particularly suited to resolve biomolecular interaction kinetics, see Fig. 3a. Compared to ensemble-averaged approaches like SPR and biolayer interferometry, single-molecule resolution has three distinct advantages that promise exciting applications in the kinetic profiling of biomolecular interactions:

(1) In contrast to ensemble-averaged approaches, single-molecule sensitivity gives access to ultralow-affinity interactions because every binding event is resolved, even if it is short. Recent efforts have therefore focused on improving the temporal resolution of single-molecule sensors to access nano- to microsecond timescales using WGM sensors75,135 and plasmon sensors35,136,137. In the future, the study of interaction pathways of intrinsically disordered proteins138,139 may be particularly exciting because their lack of tertiary structure induces fast and heterogeneous kinetic pathways that can be modulated with small-molecule drugs140.

(2) Single-molecule sensitivity gives access to underlying sample heterogeneity by e.g., analyzing the signal amplitude or bound-state lifetime of each interaction. This has recently been employed to distinguish specific from non-specific interactions in fluorescence141 and plasmonic biosensors142, to quantify heterogeneous binding kinetics in solid-state nanopores143 and WGM sensors144, and for kinetics-based protein sequencing using zero-mode waveguide sensors145. Single-molecule technologies are ideally positioned to study heterogeneities arising from e.g., post-translational modifications or conformational dynamics, where label-free sensors would further reduce the effects of fluorescent labels on the interaction kinetics11.

(3) Single-molecule sensitivity gives access to multi-step interaction pathways that are not synchronized across molecules and thereby inaccessible by ensemble-averaged approaches. Recent results on the assembly and disassembly of ferritin in nanohole sensors show the potential of single-molecule technologies to reveal every step in the assembly process58. In addition, the dynamic cooperation between multiple species is key to many processes including chaperone-mediated protein folding, signal transduction, and metabolism. They remain largely unknown due to a lack of technologies that can resolve multi-protein interactions in real-time. For these applications, the collection of sufficient statistics is crucial. Technology advances such as multiplexed and/or high-throughput sensing as discussed above will be a key enabler on this front.

Protein and DNA sequencing

DNA/RNA sequencing technology (illustrated in Fig. 3b) has advanced rapidly with the advent of single-molecule approaches, including single-molecule fluorescent synthesis labeling techniques involving zero-mode waveguides and label-free nanopore sequencing115,146,147. Some early proposals suggested combining Raman spectroscopy with nanoaperture optical tweezers and nanopore translation to achieve specific base identification without the need for labels64. However, a high level of specificity was achieved with the nanopore itself so the Raman-based approaches did not gain traction at that time.

Newer technologies are attempting to sequence proteins, including identifying post-translational modifications148. This is considerably more complicated than a 4-base alphabet; and Raman-based approaches are re-emerging as candidates. For example, peptide identification with nanophotonic/plasmonic resonators used to enhance the Raman signal to the single-molecule level has been demonstrated149. This has applications related to the immune response, including immunotherapy. An ambitious goal is to perform single-cell proteomics—mass spectrometry is one of the key tools in this field; however, truly single-molecule approaches, such as nanopores115, are also aimed at solving this problem. It is possible that label-free optical approaches may also have impact in this application since they are well-suited for small populations (particularly for cases where there is a large dynamic range), as well as for problems where the proteins to be identified are not necessarily known beforehand.

High throughput SPR150, dielectric resonators151,152, and biolayer interferometry153 are used widely for identifying antibody–antigen interactions and mapping out the epitopes (binding regions) associated with antigens of interest. Single-molecule approaches offer the potential to interrogate antibodies from single cells, measure on and off binding kinetics at the single-molecule level for a wide range of affinities. This is not only highly sensitive and potentially cost-saving (requiring growing fewer cells in less time, and quickly eliminating weak candidates), but also can reveal multi-step kinetics not readily accessible from ensemble measurements. In the future, optical tweezer methods may monitor these interactions without the need for surface immobilization that is typically used65.

Molecular diagnostics

In disease diagnostics and biomedical research, sensitive biosensors already offer transformative capabilities by enabling the detection of disease biomarkers at extraordinarily low concentrations (see Fig. 3c). Workhorse technologies in the diagnostics sector are currently focused on PCR, ELISA, electrochemistry, and lateral flow assays. These are all highly sensitive and/or specific and employ ensemble-based sensing approaches to accumulate sufficient signal. Going forward, developing single-molecule sensing capabilities for diagnostics is a particularly promising area. Recent results already demonstrate single-molecule diagnostic assays for ssDNA154,155, protein156,157,158 and miRNA142. From an application perspective, diagnostic assays with single-molecule sensitivity have two clear advantages over ensemble assays:

First, a wide range of diseases, including sepsis and heart failure, involve fluctuating biomarker levels, making continuous monitoring valuable for early diagnosis. Continuous glucose monitors have notably improved life for diabetic patients. Low-affinity capture probes offer promise for continuous sensing, but their sensitivity is limited by the need to use low-affinity (reversible) capture probes with micromolar dissociation constants. Single-molecule techniques overcome this because they enable the detection of biomarkers even at concentrations far below the dissociation constant of the capture probe. Recent advances use particle mobility to monitor low-affinity interactions at picomolar levels155,159, and combine this with electromagnetic forces to actively tune binding kinetics and accelerate mass transport160, while single-molecule plasmon sensing has achieved femtomolar detection in complex fluids142,154.

Second, if we are interested in detecting a particular species in a complex mixture one can potentially exploit single-molecule metrics to distinguish species. In fact, this challenge is common to other modalities such as mass spectrometry and electron microscopy, which possess immense detection sensitivities, but similarly struggle with complex environments. Kinetic fingerprinting is a powerful technique in single-molecule diagnostic technologies that leverages the unique binding and unbinding dynamics of biomolecular interactions to potentially enhance specificity and sensitivity141,142. Unlike traditional assays that rely solely on equilibrium binding, kinetic fingerprinting analyzes the temporal patterns of individual binding events (e.g., the bound-state lifetime) to distinguish between closely related targets143,161,162. This approach is particularly valuable in complex biological fluids encountered in diagnostics, where background noise and nonspecific interactions can obscure signals. These approaches are still in their infancy, but can have a large impact on the sensitivity, accuracy, and versatility of future diagnostic platforms.

Beyond diagnostics, label-free single-molecule technologies may find their way into probing intracellular dynamics. WGM barcodes have already been used for conducting multiparameter single-cell assays156,163, while iSCAT microscopy has been used for label-free tracking of organelles in living cells164. These technologies open up new possibilities for real-time, high-resolution biological monitoring within living systems, at the level of single molecules, without the requirement of fluorescent labeling.

Outlook

Label-free single-molecule biosensing represents a rapidly advancing frontier in analytical science, offering the capability to detect and characterize individual biomolecular interactions without the need for fluorescent or enzymatic labels. Recent technological progress in nanophotonics, plasmonics, and interferometry — combined with innovations in surface functionalization, fluidics, and data processing — has significantly enhanced the sensitivity and temporal resolution of these platforms. Looking forward, the convergence of label-free single-molecule detection with machine learning and lab-on-a-chip technologies is expected to yield compact, high-throughput biosensing systems capable of autonomous operation in clinical, environmental, and industrial settings, thereby redefining the scope and scalability of precision biosensing. Achieving these goals presents new challenges: the field is progressing from a monodisciplinary to a highly multidisciplinary effort where new collaborations that bridge the fields of optics, protein biology, and data science will be essential to progress.

Data availability

Not applicable.

References

Coons, A. H., Creech, H. J. & Jones, R. N. Immunological properties of an antibody containing a fluorescent group. Exp. Biol. Med. 47, 200–202 (1941).

Engvall, E. & Perlmann, P. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantitative assay of immunoglobulin G. Immunochemistry 8, 871–874 (1971).

Van Weemen, B. K. & Schuurs, A. H. W. M. Immunoassay using antigen—enzyme conjugates. FEBS Lett. 15, 232–236 (1971).

Rabinow, P. Making PCR: A Story of Biotechnology (The University of Chicago Press, 2011).

Kretschmann, E. & Raether, H. Notizen: radiative decay of non radiative surface plasmons excited by light. Z. Naturforsch. 23, 2135–2136 (1968).

Otto, A. Excitation of nonradiative surface plasma waves in silver by the method of frustrated total reflection. Z. Physik 216, 398–410 (1968).

B. Liedberg, C. Nylander, and I. Lundström, Biosensing with surface plasmon resonance — how it all started. Biosens. Bioelectron. 10, i–ix (1995).

Moerner, W. E. & Kador, L. Optical detection and spectroscopy of single molecules in a solid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2535–2538 (1989).

Orrit, M. & Bernard, J. Single pentacene molecules detected by fluorescence excitation in a p -terphenyl crystal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 2716–2719 (1990).

Macklin, J. J., Trautman, J. K., Harris, T. D. & Brus, L. E. Imaging and time-resolved spectroscopy of single molecules at an interface. Science 272, 255–258 (1996).

Liang, F., Guo, Y., Hou, S. & Quan, Q. Photonic-plasmonic hybrid single-molecule nanosensor measures the effect of fluorescent labels on DNA-protein dynamics. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602991 (2017).

Taylor, A. B. & Zijlstra, P. Single-molecule plasmon sensing: current status and future prospects. ACS Sens. 2, 1103–1122 (2017).

Subramanian, S., Wu, H., Constant, T., Xavier, J. & Vollmer, F. Label-free optical single-molecule micro- and nanosensors. Adv. Mater. 30, 1801246 (2018).

Dey, S., Dolci, M. & Zijlstra, P. Single-molecule optical biosensing: recent advances and future challenges. ACS Phys. Chem Au 3, 143–156 (2023).

Gordon, R., Peters, M. & Ying, C. Optical scattering methods for the label-free analysis of single biomolecules. Quart. Rev. Biophys. 57, e12 (2024).

Ginsberg, N. S., Hsieh, C.-L., Kukura, P., Piliarik, M. & Sandoghdar, V. Interferometric scattering microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 5, 23 (2025).

Min, W. et al. Imaging chromophores with undetectable fluorescence by stimulated emission microscopy. Nature 461, 1105–1109 (2009).

Gaiduk, A., Yorulmaz, M., Ruijgrok, P. V. & Orrit, M. Room-temperature detection of a single molecule’s absorption by photothermal contrast. Science 330, 353–356 (2010).

Nie, S. & Emory, S. R. Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science 275, 1102–1106 (1997).

Kneipp, K. et al. Single molecule detection using surface-enhanced raman scattering (SERS). Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1667–1670 (1997).

Roesel, T., Dahlin, A., Piliarik, M., Fitzpatrick, L. W. & Špačková, B. Label-free single-molecule optical detection. npj Biosensing 2, 32 (2025).

Raschke, G. et al. Biomolecular recognition based on single gold nanoparticle light scattering. Nano Lett. 3, 935–938 (2003).

Zijlstra, P. & Orrit, M. Single metal nanoparticles: optical detection, spectroscopy and applications. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 106401 (2011).

Peters, S. M. E., Verheijen, M. A., Prins, M. W. J. & Zijlstra, P. Strong reduction of spectral heterogeneity of gold bipyramids for single-particle and single-molecule plasmon sensing. Nanotechnology 27, a024001 (2016).

Ament, I., Prasad, J., Henkel, A., Schmachtel, S. & Sönnichsen, C. Single unlabeled protein detection on individual plasmonic nanoparticles. Nano Lett. 12, 1092–1095 (2012).

Zijlstra, P., Paulo, P. M. R. & Orrit, M. Optical detection of single non-absorbing molecules using the surface plasmon resonance of a gold nanorod. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 379–382 (2012).

Beuwer, M. A., Prins, M. W. J. & Zijlstra, P. Stochastic protein interactions monitored by hundreds of single-molecule plasmonic biosensors. Nano Lett. 15, 3507–3511 (2015).

Zhou, X., Chieng, A. & Wang, S. Label-free optical imaging of nanoscale single entities. ACS Sens. 9, 543–554 (2024).

Huo, Z. et al. Recent advances in surface plasmon resonance imaging and biological applications. Talanta 255, 124213 (2023).

Wang, S. et al. Label-free imaging, detection, and mass measurement of single viruses by surface plasmon resonance. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 16028–16032 (2010).

Ma, G. et al. Optical imaging of single-protein size, charge, mobility, and binding. Nat. Commun. 11, 4768 (2020).

Barulin, A., Roy, P., Claude, J.-B. & Wenger, J. Ultraviolet optical horn antennas for label-free detection of single proteins. Nat. Commun. 13, 1842 (2022).

Baaske, M. D., Neu, P. S. & Orrit, M. Label-free plasmonic detection of untethered nanometer-sized Brownian particles. ACS Nano 14, 14212–14218 (2020).

Asgari, N., Baaske, M. D., Ton, J. & Orrit, M. Exploring rotational diffusion with plasmonic coupling. ACS Photonics 11, 634–641 (2024).

Baaske, M. D., Asgari, N., Punj, D. & Orrit, M. Nanosecond time scale transient optoplasmonic detection of single proteins. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl5576 (2022).

Visser, E. W. A., Horáček, M. & Zijlstra, P. Plasmon rulers as a probe for real-time microsecond conformational dynamics of single molecules. Nano Lett. 18, 7927–7934 (2018).

Ye, W. et al. Conformational dynamics of a single protein monitored for 24 h at video rate. Nano Lett. 18, 6633–6637 (2018).

Velasco, L., Islam, A. N., Kundu, K., Oi, A. & Reinhard, B. M. Two-color interferometric scattering (iSCAT) microscopy reveals structural dynamics in discrete plasmonic molecules. Nanoscale 16, 11696–11704 (2024).

Armstrong, R. E., Horáček, M. & Zijlstra, P. Plasmonic assemblies for real-time single-molecule biosensing. Small 16, 2003934 (2020).

Ma, G., Wan, Z., Yang, Y., Jing, W. & Wang, S. Three-dimensional tracking of tethered particles for probing nanometer-scale single-molecule dynamics using a plasmonic microscope. ACS Sens. 6, 4234–4243 (2021).

Pang, Y. & Gordon, R. Optical trapping of a single protein. Nano Lett. 12, 402–406 (2012).

Yoo, D. et al. Low-power optical trapping of nanoparticles and proteins with resonant coaxial nanoaperture using 10 nm gap. Nano Lett. 18, 3637–3642 (2018).

Saleh, A. A. E. & Dionne, J. A. Toward efficient optical trapping of sub-10-nm particles with coaxial plasmonic apertures. Nano Lett. 12, 5581–5586 (2012).

Yang, W., Van Dijk, M., Primavera, C. & Dekker, C. FIB-milled plasmonic nanoapertures allow for long trapping times of individual proteins. iScience 24, 103237 (2021).

Kotnala, A. & Gordon, R. Double nanohole optical tweezers visualize protein p53 suppressing unzipping of single DNA-hairpins. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 1886 (2014).

Babaei, E., Wright, D. & Gordon, R. Fringe dielectrophoresis nanoaperture optical trapping with order of magnitude speed-up for unmodified proteins. Nano Lett. 23, 2877–2882 (2023).

Wheaton, S. & Gordon, R. Molecular weight characterization of single globular proteins using optical nanotweezers. Analyst 140, 4799–4803 (2015).

Juan, M. L., Gordon, R., Pang, Y., Eftekhari, F. & Quidant, R. Self-induced back-action optical trapping of dielectric nanoparticles. Nat. Phys. 5, 915–919 (2009).

Mestres, P., Berthelot, J., Aćimović, S. S. & Quidant, R. Unraveling the optomechanical nature of plasmonic trapping. Light Sci. Appl. 5, e16092–e16092 (2016).

Peters, M., McIntosh, D., Branzan Albu, A., Ying, C. & Gordon, R. Label-free tracking of proteins through plasmon-enhanced interference. ACS Nanosci. Au 4, 69–75 (2024).

Xu, Z., Song, W. & Crozier, K. B. Direct particle tracking observation and Brownian dynamics simulations of a single nanoparticle optically trapped by a plasmonic nanoaperture. ACS Photonics 5, 2850–2859 (2018).

Verschueren, D. V. et al. Label-free optical detection of DNA translocations through plasmonic nanopores. ACS Nano 13, 61–70 (2019).

Jiang, Q. et al. Adhesion layer influence on controlling the local temperature in plasmonic gold nanoholes. Nanoscale 12, 2524–2531 (2020).

Ying, C. et al. Watching single unmodified enzymes at work. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2107.06407 (2021).

Yang-Schulz, A. et al. Direct observation of small molecule activator binding to single PR65 protein. npj Biosens. 2, 2 (2025).

Peters, M. et al. Energy landscape of conformational changes for a single unmodified protein. npj Biosens. 1, 14 (2024).

Booth, L. S. et al. Modelling of the dynamic polarizability of macromolecules for single-molecule optical biosensing. Sci. Rep. 12, 1995 (2022).

Yousefi, A. et al. Structural flexibility and disassembly kinetics of single ferritin molecules using optical nanotweezers. ACS Nano 18, 15617–15626 (2024).

Yousefi, A. et al. Optical monitoring of in situ iron loading into single, native ferritin proteins. Nano Lett. 23, 3251–3258 (2023).

Kotnala, A., Wheaton, S. & Gordon, R. Playing the notes of DNA with light: extremely high frequency nanomechanical oscillations. Nanoscale 7, 2295–2300 (2015).

Wheaton, S., Gelfand, R. M. & Gordon, R. Probing the Raman-active acoustic vibrations of nanoparticles with extraordinary spectral resolution. Nat. Photon 9, 68–72 (2015).

Kerman, S. et al. Raman fingerprinting of single dielectric nanoparticles in plasmonic nanopores. Nanoscale 7, 18612–18618 (2015).

Jones, S., Al Balushi, A. A. & Gordon, R. Raman spectroscopy of single nanoparticles in a double-nanohole optical tweezer system. J. Opt. 17, 102001 (2015).

Chen, C., Dorpe, P. V., Cheng, K., Stakenborg, T. & Lagae, L. Plasmonic force manipulation in nanostructures. United States patent US9862601B2 (2018).

Peri, S. S. S. et al. Detection of specific antibody-ligand interactions with a self-induced back-action actuated nanopore electrophoresis sensor. Nanotechnology 31, 085502 (2020).

Raza, M. U., Peri, S. S. S., Ma, L.-C., Iqbal, S. M. & Alexandrakis, G. Self-induced back action actuated nanopore electrophoresis (SANE). Nanotechnology 29, 435501 (2018).

Gorodetsky, M. L., Savchenkov, A. A. & Ilchenko, V. S. Ultimate Q of optical microsphere resonators. Opt. Lett. 21, 453 (1996).

Vollmer, F. et al. Protein detection by optical shift of a resonant microcavity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 4057–4059 (2002).

Arnold, S., Khoshsima, M., Teraoka, I., Holler, S. & Vollmer, F. Shift of whispering-gallery modes in microspheres by protein adsorption. Opt. Lett. 28, 272 (2003).

Vollmer, F. & Yu, D. Optical Whispering Gallery Modes for Biosensing: From Physical Principles to Applications (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Baaske, M. D., Foreman, M. R. & Vollmer, F. Single-molecule nucleic acid interactions monitored on a label-free microcavity biosensor platform. Nat. Nanotechol. 9, 933–939 (2014).

Vincent, S., Subramanian, S. & Vollmer, F. Optoplasmonic characterisation of reversible disulfide interactions at single thiol sites in the attomolar regime. Nat. Commun. 11, 2043 (2020).

Subramanian, S., Kalani Perera, K. M., Pedireddy, S. & Vollmer, F. Optoplasmonic whispering gallery mode sensors for single molecule characterization: a practical guide. in Single Molecule Sensing Beyond Fluorescence (eds Bowen, W., Vollmer, F., & Gordon, R.) 37–96 (Springer International Publishing, 2022).

Baaske, M. D. & Vollmer, F. Optical observation of single atomic ions interacting with plasmonic nanorods in aqueous solution. Nat. Photon 10, 733–739 (2016).

Subramanian, S. et al. Sensing enzyme activation heat capacity at the single-molecule level using gold-nanorod-based optical whispering gallery modes. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4, 4576–4583 (2021).

Zhu, J. et al. On-chip single nanoparticle detection and sizing by mode splitting in an ultrahigh-Q microresonator. Nat. Photon 4, 46–49 (2010).

Tang, S.-J. et al. Single-particle photoacoustic vibrational spectroscopy using optical microresonators. Nat. Photon. 17, 951–956 (2023).

Vallance, C., Trichet, A. A. P., James, D., Dolan, P. R. & Smith, J. M. Open-access microcavities for chemical sensing. Nanotechnology 27, 274003 (2016).

Saavedra Salazar, C. A. et al. The origin of single-molecule sensitivity in label-free solution-phase optical microcavity detection. ACS Nano 19, 6342–6356 (2025).

Needham, L.-M. et al. Label-free detection and profiling of individual solution-phase molecules. Nature 629, 1062–1068 (2024).

Zernike, F. Phase contrast, a new method for the microscopic observation of transparent objects. Physica 9, 686–698 (1942).

Ploem, J. S. Reflection-contrast microscopy as a tool for investigation of the attachment of living cells to a glass surface. In Mononuclear Phagocytes in Immunity, Infection and Pathology (van Furth, R., ed.) Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 405–421 (1975).

Curtis, A. S. G. The mechanism of adhesion of cells to glass. J. Cell. Biol. 20, 199–215 (1964).

Lindfors, K., Kalkbrenner, T., Stoller, P. & Sandoghdar, V. Detection and spectroscopy of gold nanoparticles using supercontinuum white light confocal microscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 037401 (2004).

Arbouet, A. et al. Direct measurement of the single-metal-cluster optical absorption. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 127401 (2004).

Boyer, D., Tamarat, P., Maali, A., Lounis, B. & Orrit, M. Photothermal imaging of nanometer-sized metal particles among scatterers. Science 297, 1160–1163 (2002).

Lin, S., He, Y., Feng, D., Piliarik, M. & Chen, X.-W. Optical fingerprint of flat substrate surface and marker-free lateral displacement detection with angstrom-level precision. Phys. Rev. Lett. 129, 213201 (2022).

Kukura, P., Celebrano, M., Renn, A. & Sandoghdar, V. Imaging a single quantum dot when it is dark. Nano Lett. 9, 926–929 (2009).

Piliarik, M. & Sandoghdar, V. Direct optical sensing of single unlabelled proteins and super-resolution imaging of their binding sites. Nat. Commun. 5, 4495 (2014).

Kukura, P. et al. High-speed nanoscopic tracking of the position and orientation of a single virus. Nat. Methods 6, 923–927 (2009).

Chong, S., Min, W. & Xie, X. S. Ground-state depletion microscopy: detection sensitivity of single-molecule optical absorption at room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 3316–3322 (2010).

Kukura, P., Celebrano, M., Renn, A. & Sandoghdar, V. Single-molecule sensitivity in optical absorption at room temperature. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 1, 3323–3327 (2010).

Arroyo, J. O. rtega et al. Label-free, all-optical detection, imaging, and tracking of a single protein. Nano Lett. 14, 2065–2070 (2014).

Dahmardeh, M., Dastjerdi, H. M. irzaalian, Mazal, H., Köstler, H. & Sandoghdar, V. Self-supervised machine learning pushes the sensitivity limit in label-free detection of single proteins below 10 kDa. Nat. Methods 20, 442–447 (2023).

Bocquet, L. & Charlaix, E. Nanofluidics, from bulk to interfaces. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 1073–1095 (2010).

Špačková, B. et al. Label-free nanofluidic scattering microscopy of size and mass of single diffusing molecules and nanoparticles. Nat. Methods 19, 751–758 (2022).

Altenburger, B. et al. Label-free imaging of catalytic H2 O2 decomposition on single colloidal Pt nanoparticles using nanofluidic scattering microscopy. ACS Nano 17, 21030–21043 (2023).

Altenburger, B., Fritzsche, J. & Langhammer, C. Femtoliter batch reactors for nanofluidic scattering spectroscopy analysis of catalytic reactions on single nanoparticles. Small Methods 2500693 (2025).

Altenburger, B., Fritzsche, J. & Langhammer, C. Visible light spectroscopy of liquid solutes from femto- to attoliter volumes inside a single nanofluidic channel. ACS Nano 19, 2857–2869 (2025).

Andersson, J. et al. Polymer brushes on silica nanostructures prepared by aminopropylsilatrane click chemistry: superior antifouling and biofunctionality. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 10228–10239 (2023).

Young, G. et al. Quantitative mass imaging of single molecules in solution. Science 360, 423–427 (2018).

Paul, S. S., Lyons, A., Kirchner, R. & Woodside, M. T. Quantifying oligomer populations in real time during protein aggregation using single-molecule mass photometry. ACS Nano 16, 16462–16470 (2022).

Moerner, W. E. A dozen years of single-molecule spectroscopy in physics, chemistry, and biophysics. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 910–927 (2002).

Kim, E., Baaske, M. D., Schuldes, I., Wilsch, P. S. & Vollmer, F. Label-free optical detection of single enzyme-reactant reactions and associated conformational changes. Sci. Adv. 3, e1603044 (2017).

Becker, J. et al. A quantitative description for optical mass measurement of single biomolecules. ACS Photonics 10, 2699–2710 (2023).

Leake, M. C. Correlative approaches in single-molecule biophysics: a review of the progress in methods and applications. Methods 193, 1–4 (2021).

Bustamante, C. J., Chemla, Y. R., Liu, S. & Wang, M. D. Optical tweezers in single-molecule biophysics. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 1, 25 (2021).

Choi, H.-K. et al. Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman scattering as a probe of single-molecule surface reactions: promises and current challenges. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 3008–3017 (2019).

“Surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy | Nature Reviews Methods Primers” https://www.nature.com/articles/s43586-023-00261-8.

Indukuri, S. R. K. C. et al. Enhanced chiral sensing at the few-molecule level using negative index metamaterial plasmonic nanocuvettes. ACS Nano 17289–17297 (2022).

“LUMICKS,” https://www.lumicks.com/.

“Luminex,” https://www.luminexcorp.com/.

“Pacific biosciences,” https://www.pacb.com/.

“Envue technologies,” https://www.envue-technologies.com/.

“Oxford Nanopore Technologies,” https://nanoporetech.com/.

“Refeyn,” https://refeyn.com/.

“Helia biomonitoring,” https://www.heliabiomonitoring.com/.

Du Nguyen, D. et al. Recent advances in dynamic single-molecule analysis platforms for diagnostics: Advantages over bulk assays and miniaturization approaches. Biosens. Bioelectron. 278, 117361 (2025).

Quesada-González, D. & Merkoçi, A. Mobile phone-based biosensing: an emerging diagnostic and communication technology. Biosens. Bioelectron. 92, 549–562 (2017).

Soler, M., Huertas, C. S. & Lechuga, L. M. Label-free plasmonic biosensors for point-of-care diagnostics: a review. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 19, 71–81 (2019).

Semeniak, D., Cruz, D. F., Chilkoti, A. & Mikkelsen, M. H. Plasmonic fluorescence enhancement in diagnostics for clinical tests at point-of-care: a review of recent technologies. Adv. Mater. 35, 2107986 (2023).

Trofymchuk, K. et al. Addressable nanoantennas with cleared hotspots for single-molecule detection on a portable smartphone microscope. Nat. Commun. 12, 950 (2021).

Altug, H., Oh, S.-H., Maier, S. A. & Homola, J. Advances and applications of nanophotonic biosensors. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 5–16 (2022).

Steinmetz, L. M. & Jones, A. Sensing a revolution. Mol. Syst. Biol. 12, MSB166873 (2016).

Hassan, D. et al. Cross-modality transformations in biological microscopy enabled by deep learning. Adv. Photon. 6, 064001 (2024).

Langhammer, C. et al. Label-free mass and size characterization of few-kDa biomolecules by hierarchical vision transformer augmented nanofluidic scattering microscopy. Res. Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6753006/v1 (2025).

Ballard, Z. S. et al. Computational sensing using low-cost and mobile plasmonic readers designed by machine learning. ACS Nano 11, 2266–2274 (2017).

Bai, B. et al. Deep learning-enabled virtual histological staining of biological samples. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 57 (2023).

Helgadottir, S. et al. Extracting quantitative biological information from bright-field cell images using deep learning. Biophys. Rev. 2, 031401 (2021).

Stollmann, A. et al. Molecular fingerprinting of biological nanoparticles with a label-free optofluidic platform. Nat. Commun. 15, 4109 (2024).

Wang, Y., Zhao, Y., Bollas, A., Wang, Y. & Au, K. F. Nanopore sequencing technology, bioinformatics and applications. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1348–1365 (2021).

Ota, S. et al. Ghost cytometry. Science 360, 1246–1251 (2018).

Del'Haye, P. et al. Optical frequency comb generation from amonolithic microresonator. Nature 450, 1214–1217 (2007).

Eerqing, N., Zossimova, E., Subramanian, S., Wu, H.-Y. & Vollmer, F. Monitoring single DNA docking site activity with sequential modes of an optoplasmonic whispering-gallery mode biosensor. Sensors 25, 6059 (2025).

Rosenblum, S., Lovsky, Y., Arazi, L., Vollmer, F. & Dayan, B. Cavity ring-up spectroscopy for ultrafast sensing with optical microresonators. Nat. Commun. 6, 6788 (2015).

Grabenhorst, L., Sturzenegger, F., Hasler, M., Schuler, B. & Tinnefeld, P. Single-molecule FRET at 10 MHz count rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3539–3544 (2024).

Nooteboom, S. W. et al. Real-time microsecond dynamics of single biomolecules probed by plasmon-enhanced fluorescence. Nano Lett. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.4c03220 (2024).

Chowdhury, A., Nettels, D. & Schuler, B. Interaction dynamics of intrinsically disordered proteins from single-molecule spectroscopy. Ann. Rev. Biophys. 52, 433–462 (2023).

Zargarbashi, S. et al. Direct observation of conformational dynamics in intrinsically disordered proteins at the single-molecule level. Preprint at bioRxiv https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.05.26.656162v1 (2025).

Arkin, M. R., Tang, Y. & Wells, J. A. Small-molecule inhibitors of protein-protein interactions: progressing toward the reality. Chem. Biol. 21, 1102–1114 (2014).

Johnson-Buck, A. et al. Kinetic fingerprinting to identify and count single nucleic acids. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 730–732 (2015).

de Miranda, L. O. et al. A dynamic nanoparticle-on-film biosensor for sub-picomolar continuous monitoring in complex matrices with single-molecule resolution. ChemRxiv, https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/68651e62c1cb1ecda0aec9bb (2025).

Wei, R., Gatterdam, V., Wieneke, R., Tampé, R. & Rant, U. Stochastic sensing of proteins with receptor-modified solid-state nanopores. Nat. Nanotechnol. 7, 257–263 (2012).

Eerqing, N., Wu, H.-Y., Subramanian, S., Vincent, S. & Vollmer, F. Anomalous DNA hybridisation kinetics on gold nanorods revealed via a dual single-molecule imaging and optoplasmonic sensing platform. Nanoscale Horiz. 8, 935–947 (2023).

Reed, B. D. et al. Real-time dynamic single-molecule protein sequencing on an integrated semiconductor device. Science 378, 186–192 (2022).

Thompson, J. F. & Milos, P. M. The properties and applications of single-molecule DNA sequencing. Genome Biol. 12, 217 (2011).

Eid, J. et al. Real-time DNA sequencing from single polymerase molecules. Science 323, 133–138 (2009).

Alfaro, J. A. et al. The emerging landscape of single-molecule protein sequencing technologies. Nat. Methods 18, 604–617 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. From genotype to phenotype: raman spectroscopy and machine learning for label-free single-cell analysis. ACS Nano 18, 18101–18117 (2024).

Matharu, Z. et al. High-throughput surface plasmon resonance biosensors for identifying diverse therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Anal. Chem. 93, 16474–16480 (2021).

Abdollahramezani, S. et al. High-throughput antibody screening with high-quality factor nanophotonics and bioprinting. Preprint at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39650601/ (2024).

Hu, J. et al. Rapid genetic screening with high quality factor metasurfaces. Nat. Commun. 14, 4486 (2023).

Bates, T. A. et al. Biolayer interferometry for measuring the kinetics of protein–protein interactions and nanobody binding. Nat. Protoc. 20, 861–883 (2025).

Lamberti, V., Dolci, M. & Zijlstra, P. Continuous monitoring biosensing mediated by single-molecule plasmon-enhanced fluorescence in complex matrices. ACS Nano 18, 5805–5813 (2024).

Buskermolen, A. D. et al. Continuous biomarker monitoring with single molecule resolution by measuring free particle motion. Nat. Commun. 13, 6052 (2022).

Chen, Y., Schoeler, U., Benjamin Huang, C. & Vollmer, F. Combining whis pering-gallery mode optical biosensors with microfluidics for real-time detection of protein secretion from living cells in complex media. Small 14, 1703705 (2018).

Duy Mac, K. & Su, J. Optical biosensors for diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases. npj Biosens. 2, 20 (2025).

Gin, A., Nguyen, P.-D., Serrano, G., Alexander, G. E. & Su, J. Towards early diagnosis and screening of Alzheimer’s disease using frequency locked whispering gallery mode microtoroids. npj Biosens. 1, 9 (2024).

Visser, E. W. A., Yan, J., Van IJzendoorn, L. J. & Prins, M. W. J. Continuous biomarker monitoring by particle mobility sensing with single molecule resolution. Nat. Commun. 9, 2541 (2018).

Luo, Q. et al. Ultrasensitive single-molecule biosensor by periodic modulation of magnetic particle motion. Nano Lett. 24, 13998–14003 (2024).

Kuhn, T. & Hettich, J. Davtyan, R. & Gebhardt, J. C. M. Single molecule tracking and analysis framework including theory-predicted parameter settings. Sci. Rep. 11, 9465 (2021).

Li, J., Zhang, L., Johnson-Buck, A. & Walter, N. G. Automatic classification and segmentation of single-molecule fluorescence time traces with deep learning. Nat. Commun. 11, 5833 (2020).

Anwar, A. R., Mur, M. & Humar, M. Microcavity- and microlaser-based optical barcoding: a review of encoding techniques and applications. ACS Photonics 10, 1202–1224 (2023).

Wu, B.-K., Tsai, S.-F. & Hsieh, C.-L. Simplified interferometric scattering microscopy using low-coherence light for enhanced nanoparticle and cellular imaging. J. Phys. Chem. C 129, 5075–5085 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Interferometric plasmonic imaging and detection of single exosomes. Proc Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 10275–10280 (2018).

Acknowledgements

KM acknowledges EPSRC – EP/W013770/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.M., R.G., P.K., C.L., S.O., F.V. and P.Z. contributed equally to the discussions around the outline of the perspective, the writing of the manuscript, and creation of the figures. P.Z. initiated and coordinated the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.K. founded Refeyn Ltd. and is currently a scientific adviser. C.L. co-founded Envue technologies. S.O. is editor-in-chief for npj Biosensing. P.Z. is editor for npj Biosensing. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masuda, K., Gordon, R., Kukura, P. et al. Future directions in all-optical label-free single-molecule sensing. npj Biosensing 3, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00069-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44328-025-00069-4