Abstract

Analog processing has re-emerged as a mode of computing complex real-time algorithms since it consumes less power. Analog circuits are susceptible to mismatches, and onboard training could mitigate variations. In this study, we are presenting the use of analog floating-gate MITE-based circuits for various computations. Analog computation can provide a significant advantage in applications where signals are in the analog domain. The study uses a neural decoding task to demonstrate an application where input neural data are mapped to kinematics. The study demonstrates a real-time neural decoding task with an analog adaptive circuit. The on-chip learning algorithm is developed to adapt the parameters of the analog adaptive circuit. On-chip learning improves the overall Pearson correlation coefficient from 0.07 to 0.69 for a neural decoding task. On-chip learning and adaptation can significantly reduce the need for off-chip communication in implantable devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The energy consumption of traditional digital circuits is linked to advancements in scaling technology and the manipulation of supply voltages1. As the progression of Moore’s law begins to stagnate, the search for novel computing methodologies has intensified. Among these, analog computing has re-emerged as a significant area of interest. The interest in analog computing is driven by the need for energy-efficient solutions in continuous-time signal processing, a domain where analog techniques excel due to their lower power requirements and inherent parallelism. These attributes position analog computing as a transformative technology, particularly in applications constrained by power availability, such as edge computing devices and biomedical instrumentation2.

Historically, analog computing was primarily utilized in circuits designed for specific applications, such as front-end circuits interfacing with sensors3. Examples of such applications include neural interfaces4, biosensing readouts5, and low-power readouts for MEMS6. Recent work has expanded the use of analog circuits for computation, demonstrating their applicability in basic arithmetic operations like addition and multiplication, nonlinear computations, and solving complex operations such as differential equations7,8. This study employs translinear circuits9 to showcase various analog operations while consuming significantly low power. Field Effect Transistor-based translinear circuits operating in the subthreshold domain have shown higher energy efficiency10.

Although analog computing is noted for its energy efficiency, it suffers from mismatch and variation issues. Mismatch refers to the time-independent random variations in physical properties of identically designed devices11. Various techniques are employed to mitigate mismatches, including using larger devices, common centroid layouts, and symmetrical designs. From a circuit design perspective, strategies such as chopping, correlated double sampling, and auto zeroing are used to reduce mismatch12.

In this study, we utilize programmable translinear circuits to mitigate the variations typically associated with device fabrication. Specifically, we deploy Floating Gate (FG)-based Multiple Input Translinear Element (MITE) devices, enabling a broad spectrum of analog operations13. This research demonstrates essential analog functions such as multiplication, division, and squaring operations. Additionally, we also demonstrate complex analog computations such as neural decoding. Traditionally, decoding neural data in neural implants has required the use of multiple ADCs in the front-end or a multiplexed ADC system to digitize multiple neural channels, leading to significant power consumption, particularly in devices that employ several hundred electrodes14. Our approach, however, uses MITE-based adaptive circuits to decode broadband intracortical neural data from non-human primates performing reach-to-grasp tasks. By integrating analog computations directly into the front end, we eliminate the need for an ADC for each neural channel, significantly enhancing processing efficiency and reducing system complexity. Figure 1 shows the overall concept of neural decoding and the use of analog computation for mapping neural data to kinematics. The analog adaptive filtering technique presented in this paper would not have ADC for each of the electrodes and will not be using the DSP in inferencing mode. The mixed signal system presented in this paper could potentially remove or reduce the amount of ADC used in inferencing kinematics from neural decoding.

The mixed signal system only requires the digital processor to be active at the time of weight updates in the analog adaptive filter, minimizing the overall power consumption. Further, the proposed system uses a lesser number of ADC than a digital processor. The brain is adapted from “Human Brain.png” by Injurymap, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0. Modifications were made.

Neural data exhibits significant day-to-day variability, which presents a substantial challenge for maintaining consistent decoding accuracy15. To address this, we have developed an on-chip non-linear learning algorithm that dynamically adjusts the weights on the MITE devices. This capability enables quick calibration against the daily variations in neural data, significantly improving the resilience and accuracy of neural decoding. Such adaptive learning is crucial for the long-term, reliable operation of neural implants, as it compensates for both variations in neural data and mismatches inherent in analog circuits. All circuits were prototyped and evaluated using a Field Programmable Analog Array (FPAA)16, fabricated using a 350 nm CMOS process, which demonstrates the feasibility and effectiveness of our approach.

The paper is organized as follows. Section “Floating Gate Multiple Input Trans-linear Element (FG MITE)” describes the overall Floating Gate MITEs and presents analog how this element is used in analog computations like additional multiplications. Section “Analog Adaptive Filtering” presents an adaptive filtering system using the MITE.

Floating Gate Multiple Input Trans-linear Element (FG MITE)

Floating-gate-based multiple Input Translinear Elements (MITE) are Field-Effect Transistors (FET), which have a polysilicon gate surrounded by an insulator like silicon dioxide, which isolates the gate, which means no DC path exists from the gate terminal to the actual gate of the transistor. Multiple inputs are coupled into the floating terminal via a capacitor, as seen in Fig. 2a. Each of these inputs linearly affects the transconductance of the device. In this study, a version of 2 input MITEs is used, which has inputs coupled via capacitor C1 and C2, where the third input V3 is held constant.

To capture the non-linear behavior of the FG-based MITE devices, this study uses the EKV model17 that accurately models all the regions of operations, sub-threshold, and above the threshold. This modeling allows an accurate and smooth transition between these two regions of operation. The general form of the EKV model for a floating gate MITE device with n inputs can be written by (2) where VFG is given by (1).

The model allows designing algorithms on software while accounting for the non-linearity observed in the MITE elements. Further, it enables comparing the hardware results with the ideal results obtained from the software:

Figure 2b shows the measurement performed on an MITE device and its fit to the above equation (2) with different programming voltages (\({V}_{F{G}_{prog}}\)). In these equations, VTP represents the threshold voltage for a pMOS transistor, Ith denotes a device-specific parameter determined, and W and L are the width and length of the pMOS device, respectively. The thermal voltage is represented by UT, while CT denotes the total capacitance at the floating node, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The input voltages V1, V2, and V3 are coupled through capacitance C1, C2, and C3, respectively. The stored charge on the floating node is represented by the \({V}_{F{G}_{prog}}\). A detailed description of each device parameter can be found in refs. 13,18,19.

Programming FG MITE

The stored charge on the floating node can be precisely controlled by adding electrons to the floating node via hot-electron injection and removing trapped electrons using Fowler-Nordheim tunneling, as described by ref. 20. This process affects \({V}_{F{G}_{prog}}\).

In Fowler-Nordheim tunneling, the voltage across the tunneling capacitance Ctun is increased. This effectively increases the electric field across the oxide, allowing trapped electrons to escape through the voltage barrier across Ctun. As a result, the stored charge on the floating gate device increases, leading to a reduction in the effective threshold voltage and conductance.

Hot-electron injection in MOSFETs occurs when a sufficiently large source-to-drain voltage is applied while an adequate current flows through the device21. This process reduces the stored charge on the device, thereby increasing the effective threshold voltage and conductance. The silicon dioxide insulator acts as a voltage barrier, trapping electrons on the polysilicon floating gate permanently, which ensures long-term, non-volatile memory storage. The trapped electrons remain on the floating node without external power, contributing to the non-volatile nature of the memory.

Hot-electron injection is widely used for fine programming due to its lower variability and higher resolution compared to Fowler-Nordheim tunneling. While tunneling is used to erase the FPAA device globally, hot-electron injection is utilized for data storage on the FG MITE device, which can be employed in analog circuits.

In this work, the weights are fine-programmed using hot-electron injection, chosen for its efficiency and the ability to program individual floating gate devices effectively.

Basic arithmetic operation

Addition

Current mode addition can be performed by simply adding the drain terminals of PMOS devices together, as shown in Fig. 3a. Each PMOS device should have a Vsd > 0.2 V be on subthreshold saturation, where drain current will become independent of Vsd. An n-channel current mirror can be used in the output of an application that needs to source the summation current by providing the output current at the bias of the current of the n-mirror.

Subtraction

Similar to an addition circuit, multiple current sources can be connected at the bias and output terminals of the n-channel current mirror, as shown in Fig. 3b. The resultant output current is equal to the difference between the bias current and the output terminal input current.

Multiplication in current domain

Multiplication is a crucial operation in analog circuits, particularly in signal processing and machine learning applications. FG MITE devices enable multiplication in the format of I ∝ I1 × I2, which is essential for weighted multiplications often required in neural network computations.

The general form of the EKV model for an FG MITE, given in (2), can be simplified for a two-input FG MITE under the conditions VFG < VTP and Vds > 4∣VTP∣, known as the subthreshold saturation region. In this model, α denotes the proportionality constant, Vprog corresponds to the stored charge, VDD represents the source voltage, and \({w}_{i}=\frac{{C}_{i}}{{C}_{T}}\). The term Ci represents the input capacitance of i th input.

Since the parameters α and VDD are constant for a device, (3) can be rewritten by combining καwi as Wi and \({I}_{th}\frac{W}{L}{e}^{\frac{\kappa ({V}_{DD}-\alpha {V}_{prog})}{{U}_{t}}}\) as Io(Vprog):

By connecting three FG MITEs as shown in Fig. 4a, where two MITEs serve as inputs for the multiplication and the output is produced by a third MITE with its gates connected to the input FG MITE blocks. The current through the two input MITEs can be represented by (5), and the output current is given by (6). This can be further simplified by substituting the current equations from (5) into (6), resulting in the multiplication form Iout ∝ I1 × I2. This output current can be effectively used in multiplication calculations and perform a multiply-accumulate operation.

Figure 4b presents results from the hardware. It shows the linearity of the multiplication for I1, I2 ∈ [10, 50] currents in the range from 10 nA to 50 nA. This linearity offers more accurate multiplication results. The precision of multiplication results is limited by the driving and measuring circuits.

Division in current domain

The division is the inverse operation of multiplication, which is performed to find the quotient of two numbers. Analog current domain division could be achieved with the circuit topology shown in Fig. 5a. The circuit could be analyzed as similar to the multiplication circuit, simplified relationship between input currents I1 and I2 the output current is given in (11). Figure 5b shows the measurement results obtained from the circuit shown in Fig. 5a for I1 ∈ [20, 30] and I2 ∈ [50, 70]. These results show that linear division is achievable with MITE devices.

Square

Square and Square root operations are another useful computation that could be simply approximated with analog MITE devices. In a digital counterpart, this computation must have floating point operations to produce reasonably accurate results, requiring higher power consumption and complex dedicated circuits. A straightforward method of computing squares is using multiplication. However, to reduce the number of circuits used, the power computation circuit could be realized by connecting FG MITEs as shown in Fig. 6a.

Measured square value from hardware implementation is shown in Fig. 6b which further shows curve fitted to 2nd order polynomial in the form a(x−b)2 − c with the coefficients a ≈ 1.089 × 10−9, b ≈ 6.49A, c ≈ 1.523 × 10−7A With this circuit configuration, a square root operation could be performed by simply interchanging the inputs and outputs. Further, having n input MITEs instead of the 2 input MITEs used in this work enables computation of various powers rather than being limited to squares.

One of the advantages of FG MITES devices is that they perform general computations without having different specialized circuits for each of the computations shown. Further, these devices can be individually programmed by changing the charge of the floating node, which can reduce the mismatches and function as memory.

Analog adaptive filtering

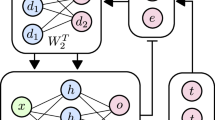

Adaptive filters are essential in signal processing and control systems due to their ability to adjust their response to changes in signal characteristics. These systems are particularly useful when signal properties are non-stationary or unknown. Unlike fixed filters, which have constant parameters, adaptive filters can dynamically update their coefficients to optimize an error criterion in real-time. Figure 7a presents a high-level block diagram of a general adaptive filter.

In this study, we focus on the adaptive filter system illustrated in Fig. 7b, where the output is given by linear combinations of convolution kernels as described by the following equation:

During the adaptive filter learning phase, the objective function used to update the coefficients is given by:

We utilize the Least Mean Square (LMS) algorithm, which iteratively updates Wi,j with a learning rate μ to minimize the error function in (16):

The charge storage capability of FG-based MITEs makes them particularly suitable as both weight storage elements and multiplicative components in an analog adaptive filter. In this study, we implement a hardware adaptive filter, as shown in Fig. 7c, utilizing FG MITE at each tap. Currently, system inputs are provided via built-in Digital to Analog Converters (DACs). In the final design, these will be replaced by analog front-end circuits that preprocess sensor inputs. Each input channel is passed through several low-pass filters, which introduce a time delay to the input signal. The delayed inputs and outputs from each low-pass filter are then fed into an array of weight storage cells. Each weight storage cell comprises two FG MITEs and a channel current mirror. This configuration allows for precise adjustment of the weight of each input by selectively increasing the current through the FG MITEs connected to the appropriate n-mirror branch via hot-electron injection. The accumulated output currents from all weight storage cells are then connected to a RAMP ADC, which charges a capacitor and triggers when the voltage across the capacitor reaches a specific value. The RAMP ADC has 10 bits of resolution and a measurement range of 18–38 nA. The resulting signal is digitized by an MSP430-based microcontroller, which processes the current output from the adaptive filter.

The weight adaptation process begins by measuring the output of the adaptive filter and evaluating the error relative to the expected output. Based on the inputs to each FG MITE, an error value is generated for each device. The weight adaptation algorithm, presented in Algorithm 1, describes the steps used to update the weights using the Hot Electron Injection process described in 2.1. During the hot electron injection fine-tuning, each FG MITE device is selected, and the tunneling terminal kept fixed at 5 V and input terminals at 3.5 V and 1 μs pulses of 5 V VDS is applied based on the number of pulses determined in Algorithm 1.

For additional details on the supporting analog circuit, including the OTA-C Supplementary Fig. 1 and RAMP ADC Supplementary Fig. 2 used in this work, see Supplementary information.

Algorithm 1

Analog Adaptive Filter Coefficient Updating Algorithm

i ← N ⊳ Number of Samples

while i > 0 do

Y[i] ← ADC ⊳ Measure ADC

i ← i − 1

end while

i ← C × T ⊳ Number of Channels (C), No. of Taps (T)

e ← 2 × μ × (D − Y) × X ⊳ Desired Signal(D), Learning rate(μ), Input Vector (X)

while i > 0 do

if e[i] < 0 then Select Switches connected to (-) ;

else Select Switches connected to (+) ;

end if

while \(\left\vert e[i]\right\vert\, > \,0\) do Inject Switch with 1us pulse

\(e[i]\leftarrow \left\vert e[i]\right\vert -1\)

end while

i ← i − 1

end while

Neural decoding using adaptive filter technique

This study employs an analog adaptive filter composed of FG MITEs to perform neural decoding. Neural decoding is the process of mapping kinematic variables (such as velocity or displacement) from the information contained in neural signals, such as action potentials. In this work, we use time-domain adaptive filtering to decode neural signals recorded from the motor cortex of a macaque monkey during an instructed delayed reach-to-grasp task, as described in ref. 22.

The dataset includes recordings from two non-human primates, a female and a male. For this study, we focus on a single trial involving the male primate and decode y component of displacement. The neural data was acquired using a Utah array with 10 × 10 electrodes. Given the significant overlap of information between multiple electrodes, reducing the input data to a lower-dimensional space can substantially decrease the complexity and cost of processing. To achieve this, we apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA), an unsupervised algorithm that transforms the original input vectors into a new coordinate system based on their principal components. PCA identifies the directions (principal components) in which the data varies the most and projects the data onto these axes, effectively reducing the dimensionality while preserving as much variance as possible.

This study uses PCA to transform the input neural signals into their principal components, thereby reducing the number of inputs to the adaptive filter. By focusing on the most significant components, PCA simplifies the data and helps retain the most relevant information for decoding. This reduction in input dimensionality leads to more efficient processing, enabling the adaptive filter to perform neural decoding more effectively. Figure 8 illustrates the signal processing chain used for decoding neural data into kinematic information. This study performs PCA offline using a software platform while the adaptive filter is implemented on analog hardware. Figure 7c shows the overall block diagram of the adaptive filter implemented on the hardware.

The brain is adapted from “Human Brain.png” by Injurymap, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0. Modifications were made. a Local Field Potential (LFP) obtained from Utah Array. b Most significant principal components extracted from LFP dataset. c After low pass filtering and normalizing the dataset using a 6-th order Butterworth filter with 25 Hz cutoff frequency and normalized by computing the z-score. d Results from the proposed adaptive filter.

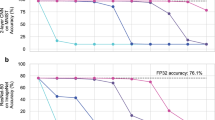

To determine the optimal number of principal components (PCA elements) that would provide high accuracy while minimizing the number of channels, this study modeled the non-linear components, such as the FG-based MITE, in Matlab using the EKV equation (Eq. (2)). Figure 9a shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predicted and reference kinematics (y-displacement) for different numbers of principal components. The results indicate that the accuracy improves with increasing principal components up to a certain point, specifically around four components. Beyond this point, the accuracy gains become marginal while the complexity of the system and power consumption increases significantly. Therefore, selecting four principal components strikes a balance between achieving high accuracy and maintaining a manageable number of analog components and power efficiency. The four principal components were passed through low-pass filters to add time delays. The sum of these weighted time delays makes a temporal convolution filter. Figure 9a presents the Pearson correlation coefficient between the predicted and reference kinematics as we increase the size of the convolution kernel. However, increasing the convolution kernel size results in higher power and complexities the analog circuit adds. Simulation results suggest that the four principal components with three time-delayed signal results offer a better correlation coefficient to the current experiment while keeping power consumption and complexity minimal. Figure 9b further illustrates the predicted and reference y-displacement over time, demonstrating the effectiveness of this approach.

a Prediction correlation from adaptive filtering with the number of principal components accounted and correlation with the number of time delays added (while keeping the PCA count to 4). b Predicted displacement from adaptive filtering with different number of principal components. c Presents results from hardware filter and the Matlab model against the reference signal. Hardware filter archive ρ = 0.69).

These selected principal components were inputs to the adaptive filter via on-chip DACs. The adaptive filter was configured with four inputs, each having three taps, as depicted in Fig. 7c. A programmable transconductance amplifier implemented the delay elements between each tap. The weights of the adaptive filter were realized using FG-based MITE blocks, which allowed for precise control and non-volatile storage of the weights. The output currents from all MITE blocks across the four channels were summed onto a single wire, and this aggregated current was sensed using a RAMP ADC. The weights were then adapted based on the weight update algorithm described in Algorithm 1.

Figure 9c presents the output of the hardware filter, comparing it with the adaptive filter implemented in Matlab and the reference displacement. Initially, with a random set of weights, the adaptive filter achieved a Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.07. The correlation improved significantly as the weights were iteratively updated using the algorithm implemented on the MSP430 microprocessor. The adaptation algorithm took 232 iterations in the hardware to reach maximum accuracy. The final Pearson correlation coefficient reached 0.69, indicating a strong alignment between the predicted and actual kinematics, thereby validating the effectiveness of the adaptive filtering approach.

The power consumption of each FG MITE and LPF was around 3 nW and 13 nW, respectively. The 4-channel 3-tapped version of the adaptive circuit shown in the 7c consumes ~140 nW of static power from 2.5 V power supply. RAMP ADC used in this work consumes 10 μW. When measuring the power consumption, the interfacing circuit power was not taken into account. Table 1 does a comparison study of systems which does neural decoding. The table shows that digital systems tend to use significant power, which makes them harder to implant, considering the thermal properties and power requirements.

Out of the works presented in Table 1 analog neural decoding of head directions is presented in ref. 23 is very similar processing with different circuit realization. This approach uses ~300 μW per channel power consumption in SPICE simulations.

Discussion

This study primarily focused on computations with CMOS-compatible non-volatile device FG MITE elements and showed an adaptive filter implementation using computations discussed as building blocks. This adaptive filter presented is beneficial for applications that require low-power, non-stationary signal processing and for applications where it is difficult to predetermine the filter coefficients. Further, on-chip learning provides robustness over the mismatches and variations in analog systems. Otherwise, the exponential current-voltage relationship makes slight mismatches of voltage, which could result in significant variations over multiple devices, making the solutions harder to scale for multiple devices.

The proposed adaptive filtering approach can be extended by increasing the number of channels and time-delayed accounts in computations. Increasing the number of channels could support systems with a higher number of electrode systems, such as Neuropixels 2.0, and increasing the number of time-delayed elements could facilitate more complex relationships.

Further, the on-chip principal component computation can be realized with FG crossbar array to a large number of electrodes similar to the memristor implementation presented in ref. 24 The PCA components currently used in this work can be replaced by the input signals directly or by an analog vector-matrix multiplier to provide a weighted sum of input signals.

Data availability

The neural dataset used in this study is published in Brochier, T., Zehl, L., Hao, Y. et al. Massively parallel recordings in macaque motor cortex during an instructed delayed reach-to-grasp task. Sci Data 5, 180055 (2018). The relevant dataset is available at https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2018.55. The circuits and other relevant materials, including underlying codes and scripts, will be made available at the request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The circuits and other relevant materials, including underlying codes and scripts, will be made available at the request from the corresponding author.

References

Chen, Z. & Gu, J. A time-domain computing accelerated image recognition processor with efficient time encoding and non-linear logic operation. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 54, 3226–3237 (2019).

Shah, S., Toreyin, H., Gungor, C. & Hasler, J. A real-time vital-sign monitoring in the physical domain on a mixed-signal reconfigurable platform. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits. Syst. 13, 1690–1699 (2019).

Ying, D. & Hall, D. A. Current sensing front-ends: a review and design guidance. IEEE Sens. J. 21, 22329–22346 (2021).

Mendrela, A. E. et al. A bidirectional neural interface circuit with active stimulation artifact cancellation and cross-channel common-mode noise suppression. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 51, 955–965 (2016).

Shenoy, V. et al. A cmos analog correlator-based painless nonenzymatic glucose sensor readout circuit. IEEE Sens. J. 14, 1591–1599 (2014).

Li, Z. et al. An analog readout circuit with a noise-reduction input buffer for mems microphone. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II: Express Briefs 69, 3983–3987 (2022).

Liang, J., Tang, X., Hariharan, S. I., Madanayake, A. & Mandal, S. A current-mode discrete-time analog computer for solving Maxwell’s equations in 2D. In Proc. IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS) 1–5 (IEEE, 2023).

Guo, N. et al. Energy-efficient hybrid analog/digital approximate computation in continuous time. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 51, 1514–1524 (2016).

Gilbert, B. Translinear circuits: an historical overview. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 9, 95–118 (1996).

Andreou, A. G. & Boahen, K. A. Translinear circuits in subthreshold MOS. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 9, 141–166 (1996).

Pelgrom, M., Duinmaijer, A. & Welbers, A. Matching properties of mos transistors. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 24, 1433–1439 (1989).

Enz, C. & Temes, G. Circuit techniques for reducing the effects of op-amp imperfections: autozeroing, correlated double sampling, and chopper stabilization. Proc. IEEE 84, 1584–1614 (1996).

Minch, B. A., Diorio, C., Hasler, P. & Mead, C. A. Translinear circuits using subthreshold floating-gate MOS transistors. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 9, 167–179 (1996).

Jun, J. J. et al. Fully integrated silicon probes for high-density recording of neural activity. Nature 551, 232–236 (2017).

Huang, G. et al. Discrepancy between inter- and intra-subject variability in EEG-based motor imagery brain-computer interface: Evidence from multiple perspectives. Front. Neurosci. 17, 1122661 (2023).

George, S. et al. A programmable and configurable mixed-mode FPAA SoC. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 24, 2253–2261 (2016).

Enz, C. C., Krummenacher, F. & Vittoz, E. A. An analytical mos transistor model valid in all regions of operation and dedicated to low-voltage and low-current applications. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 8, 83–114 (1995).

Mead, C. Analog VLSI and Neural Systems (Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., 1989).

Yang, K. & Andreou, A. G. A multiple input differential amplifier based on charge sharing on a floating-gate MOSFET. Analog Integr. Circuits Signal Process. 6, 197–208 (1994).

Hasler, P. Floating-gate devices, circuits, and systems. In Fifth International Workshop on System-on-Chip for Real-Time Applications (IWSOC'05) 482–487 (IEEE, 2005).

Kim, S., Shah, S. & Hasler, J. Calibration of floating-gate SoC FPAA system. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 25, 2649–2657 (2017).

Brochier, T. et al. Massively parallel recordings in macaque motor cortex during an instructed delayed reach-to-grasp task. Sci. Data 5, 180055 (2018).

Rapoport, B. I. et al. A biomimetic adaptive algorithm and low-power architecture for implantable neural decoders. Annu Int Conf. IEEE Eng. Med Biol. Soc. 2009, 4214–4217 (2009).

Choi, S., Sheridan, P. & Lu, W. D. Data clustering using memristor networks. Sci. Rep. 5, 10492 (2015).

Chen, Y., Yao, E. & Basu, A. A 128-channel extreme learning machine-based neural decoder for brain machine interfaces. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 10, 679–692 (2016).

An, H. et al. A power-efficient brain-machine interface system with a sub-mw feature extraction and decoding ASIC demonstrated in nonhuman primates. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 16, 395–408 (2022).

Shaeri, M. A. et al. 33.3 MiBMI: A 192/512-channel 2.46 mm2 miniaturized brain-machine interface chipset enabling 31-class brain-to-text conversion through distinctive neural codes. In Proc. IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC) Vol. 67, 546–548 (IEEE, 2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation Award #2338159.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S. conducted the experiments, collected and analyzed the data, prepared Figures 1, 3–9, A1, and wrote the manuscript. S.S. contributed to the overall conceptualization, data analysis, Figure 2 and manuscript writing. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sonnadara, C., Shah, S. Real-time analog processing with on-chip learning using multiple-input translinear elements. npj Unconv. Comput. 2, 11 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00022-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00022-8

This article is cited by

-

Edge intelligence through in-sensor and near-sensor computing for the artificial intelligence of things

npj Unconventional Computing (2025)