Abstract

Neuromorphic (brain-inspired) photonics accelerates AI1 with high-speed, energy-efficient solutions for RF communication2, image processing3,4, and fast matrix multiplication5,6. However, integrated neuromorphic photonic hardware faces size constraints that limit network complexity. Recent advances in photonic quantum hardware7 and performant trainable quantum circuits8 offer a path to more scalable photonic neural networks. Here, we show that a combination of classical network layers with trainable continuous variable quantum circuits yields hybrid networks with improved trainability and accuracy. On a classification task, these hybrid networks match the performance of classical networks nearly twice their size. These performance benefits remain even when evaluated at state-of-the-art bit precisions for classical and quantum hardware. Finally, we outline available hardware and a roadmap to hybrid architectures. These hybrid quantum-classical networks demonstrate a unique route to enhance the computational capacity of integrated photonic neural networks without increasing the network size.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Neuromorphic photonics is a promising accelerator for artificial intelligence and brain-inspired computing1, capable of real-time signal processing of radio and optical signals2,9, image processing3,4, and fast matrix multiplication5,6. Neuromorphic networks consist of layers of interconnected neurons, as illustrated in Fig. 1. Like the brain, the complexity of these networks is primarily determined by the number of connections between these neurons. In neuromorphic photonic platforms, such as silicon10, silicon nitride11, and lithium niobate6, neurons are implemented using photonic resonators, waveguides, modulators, and detectors12,13, resulting in high bandwidth, low loss, and ultra-low latency networks1,14. However, the relatively large size of these optical components, particularly in comparison with their electronic counterparts, limits the scalability and complexity of neuromorphic photonic networks.

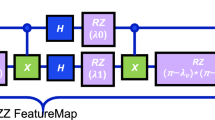

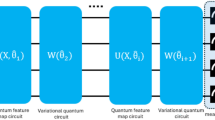

a A one-layer two-qumode hybrid neural network, network A, consisting of input, encoding, a CV neural network15, and output layers. Data is fed into the classical input layer. Outputs from this layer are then input into the encoding gates21,22. A single CV neural network layer is labeled as \({{\mathcal{L}}}^{(h)}\). This specific network contains 120 parameters. The gates in the quantum neural network are described in Section “Hybrid continuous variable neural networks” and Supplementary Note Simulation and Cutoff Dimension. b A corresponding all-classical network equivalent to the hybrid network, network B. Here, the hidden layer W(h) is a classical layer with two neurons. In the lower right, a mathematical description illustrates the operations occurring at each layer of the network. This network has 124 parameters. c Feature 1 and Feature 6 from the validation set of the classification dataset are shown. The shaded region in each subplot surrounds all the samples of the corresponding class. d The number of parameters in both the hybrid and classical networks as a function of the number of modes. The inset shows the scaling of the input, hidden, and output layers for the two-qumode hybrid network.

Here, we explore a new route to increasing the network complexity, namely by replacing layers of classical neurons with a quantum neural network. Specifically, we envision using a continuous variable (CV) photonic network15,16,17, which is built on the same platforms and employs the same devices as typical neuromorphic photonic systems. Here, using an exemplary classification task, we show that hybrid quantum-classical neuromorphic networks can outperform fully classical networks in both training efficiency and overall accuracy, consistent with previous information-theoretic analysis8. This advantage is particularly pronounced in smaller networks with ≲250 weights (for reference, a state-of-the-art 3-layer 6 × 6 × 6 × 6 integrated photonic network has 132 weights18). Finally, we show that within this size range, hybrid neuromorphic networks are sufficiently robust to noise, reinforcing that hybrid quantum-classical photonics may play an important role in unlocking the full potential of brain-inspired hardware.

Results

Hybrid continuous variable neural networks

We begin by constructing models of both hybrid and fully classical neural networks, as illustrated in Fig. 1a, b, respectively. The difference between the two is that the hidden layer of the classical network (shaded region of Fig. 1b) is replaced by a CV quantum neural network (CVQNN)15 as indicated in the shaded region of the hybrid network (Fig. 1a). Both networks have identical input \(\left({W}^{(i)}\right)\) and output \(\left({W}^{(o)}\right)\) layers, which are standard fully-connected classical feed-forward networks—the most ubiquitous network type in deep learning19—whose dimensions depend on the task to be performed. The CVQNN was used as it mimics the key operations of classical artificial neurons: matrix multiplication, bias, and non-linearity (see ref. 15 for more information). For our study, we select a classification task which, while challenging, is well-suited to feed-forward neural networks. Specifically, we synthetically generate 1000 samples20 (700 for training and 300 for validation) evenly distributed across four classes, each with eight features (see Methods Synthetic Dataset). An example of this distribution, for two of the eight features, is shown in Fig. 1c, where shaded regions represent the area encompassed by each class for the two selected features. The overlap of these regions demonstrates that it is impossible to classify each sample simply based on two features, necessitating the use of all eight features. Consequently, our input layer has eight neurons, while the output layer contains four neurons.

To construct the hybrid neural network, the classical hidden layers \(\left({W}^{(h)}\right)\) are replaced by an encoding layer21,22 followed by a CV quantum neural network (\({{\mathcal{L}}}^{(h)}\), CVQNN)15 (Fig. 1a). CVQNNs can be trained via backpropagation23 (see Supplementary Note Parameter Shift Rule) and, along with the encoding layer, can be realized with photonic elements on-chip7,24,25,26. As shown in Fig. 1a, both the encoding layer and the CVQNN are made of the same photonic elements. In addition to the linear unitary layers, \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{\{1,2\}}\)5,7, the CVQNN is comprised of a series of displacement \({\mathcal{D}}\), squeezing \({\mathcal{S}}\) and non-Gaussian Φ gates. See Supplemental Notes II and IV for more information on the quantum gates.

Although quantum gates impose more stringent requirements than their classical counterparts, particularly with respect to losses or noise, both squeezing7,24,25 and displacement27,28 elements can now be routinely fabricated on-chip. Non-Gaussian elements have also been proposed using conditional measurement protocols17, opto-mechanical systems29, photon addition/subtraction30,31, and temporal pulse traps32, though a deterministic non-Gaussian operation has yet to be demonstrated. Here, we employ a Kerr nonlinearity15,33,34,35 as it is known to lead to highly trainable and performant networks8.

Once encoded into qumodes, the information (represented as amplitude and phase of few-photon electromagnetic fields) propagates through the CVQNN before exiting through the classical output layer. As shown in Fig. 1a, the CVQNN is comprised of \({\mathcal{D}}\), \({\mathcal{S}}\), and Φ gates, parameterized by s (\(s\in {\mathbb{C}}\)), α (\(\alpha \in {\mathbb{C}}\)), and κ (κ ∈ [0, π]), respectively. These gates are interspersed with linear interferometers \({\mathcal{U}}\), which are controlled by phase shifters, \({\overrightarrow{\theta }}_{i}\) and \({\overrightarrow{\phi }}_{i}\), enabling arbitrary unitary operations on the qumodes. In our simulation, the complex values s and α are parameterized by a separate amplitude and phase, mirroring an experimental implementation. Altogether, the parameters of the CVQNN–s, α, κ, \(\overrightarrow{\theta }\), and \(\overrightarrow{\phi }\)–along with the weights of the classical input and output layers, are trained using conventional gradient descent.

In summary, each network is characterized by P parameters, which depend on its architecture and type. For a classical network, P is simply the sum of weights in weight matrices W and bias vectors b summed over all layers. In contrast, for a hybrid network with input and output dimensions (I and O, respectively), M qumodes and L layers, the total number of parameters is given by:

Here, the first and third terms represent the number of parameters in the input and output layers, while the middle term represents the number of parameters in the quantum layer. Note that each layer of the CVQNN is identical, and each can be described by 2M(M − 1) parameters due to the MZI phase shifters, an additional 2M from post-unitary phase shifters, 2M squeezing parameters, 2M displacement parameters and M Kerr parameters. Fig. 1d shows the scaling of P as a function of the number of qumodes in the CVQNN (hidden classical layer), for 1-, 3-, and 5-layer networks. Within this range, we find classical and hybrid networks with P values between approximately 100 and 600. We are therefore able to identify networks of both types with comparable parameter counts (and hence, expected complexity) and, in what follows, we set out to compare their performance. This comparison is based on the complexity of their respective connectivity, though we acknowledge that quantum hardware poses greater implementation challenges.

Training and validation

We begin by constructing neural network models, implementing classical layers using Tensorflow36 and quantum layers with Pennylane and Strawberry Fields37,38 (see Sections “Hybrid model” and “Classical model”). We evaluate each network’s accuracy, before, during and after training, by comparing the predicted class (i.e., the output neuron oi with the highest activation) to the true class for each of the 700 training (and 300 validation) samples. The network accuracy is calculated as the ratio of correctly classified samples to the total size of the training or validation set.

As an example, we analyze the accuracy of hybrid and classical neural networks with 120 and 124 parameters, respectively, corresponding to the 1-layer, 2-qumode, and 2-hidden neuron networks shown in Fig. 1a, b. First, we examine the classification performance of the hybrid network at the start of training by plotting the predicted class for each sample (color-coded by the true class) along with the assigned success probability (i.e., value of the highest output neuron). We observe an almost-random distribution mapping of true vs predicted class for the unoptimized hybrid network, with an overall accuracy of only 0.58. Similarly, the maximum output activation for this unoptimized hybrid network is low, peaking at 0.61 for class 3 (see inset), but generally remaining well below 0.4. That is, before training, the hybrid network is both “hesitant” and inaccurate. The results of the untrained classical network, shown in Fig. 2b, are qualitatively similar but poorer, with an overall accuracy of only 0.47 and peak output probability of 0.38.

a The maximum output activations for an untrained 120-parameter hybrid network, network A. The x-axis represents the predicted class, while the color indicates the true class. The inset shows the maximum output activations for all samples predicted as class three. b The maximum output activations for an untrained 124-parameter classical network, B. c The maximum output activations for network A after training. d The maximum output activations for a trained network B. e The training and validation accuracy curves for networks A and B.

We train the network parameters over 200 epochs, updating the weights 22 times per epoch. After each epoch, we compute the network accuracy using both the training (solid curves) and validation (dashed curves) sets, as shown in Fig. 2e. The overlap of the training and validation accuracy curves indicates that no overfitting occurs. As expected, the network accuracy improves throughout the training, reaching 0.87 for the hybrid network and 0.79 for the classical network, demonstrating the advantage of incorporating quantum layers.

The advantage of incorporating quantum layers becomes more evident when examining the classification performance of both hybrid and classical networks after training (at epoch 195), as shown in Fig. 2c, d, respectively. The hybrid network consistently classifies all samples correctly, with maximum output probabilities exceeding 0.80 across all four classes. In contrast, while the fully classical network correctly classifies classes one and four with output probabilities reaching 0.91, it struggles with classes 2 and 3. Notably, for class 3, the trained fully-classical network is already outperformed by the untrained hybrid network.

Larger networks

To further investigate the differences between hybrid and classical photonic neural networks, we extend our analysis to networks with varying numbers of qumodes/neurons and layers (c.f., Fig. 1d). In total, we train 342 hybrid networks and 518 classical networks, grouped into sets of 10–30 for hybrid networks and sets of 20–30 for classical networks, with each group’s network size ranging from 69 to 590 parameters. For classical devices, this approximately corresponds to single-layer 8 × 8 and 24 × 24 classical networks with estimated photonic footprints of 0.168 mm2 and 1.656 mm2, respectively (see Supplementary Note Implementations of Quantum Gates for details). To establish a threshold for well-trained networks, we fit a non-probabilistic linear support vector machine to the data, achieving an accuracy of 0.72 (see Supplementary Note PCA and Linear Fitting). Networks exceeding this threshold are considered well-trained, while those with an accuracy of around 0.25 are considered failed, as random selection would yield an accuracy of 0.25. The aggregate results for the 120-parameter hybrid networks and 124-parameter classical networks are shown in Fig. 3a. This analysis further highlights the advantages of quantum layers, demonstrating that significantly more highly accurate hybrid networks are trained compared to classical ones. More specifically, the average well-trained hybrid network achieves an accuracy of 0.85 ± 0.01, whereas fully classical networks have an average accuracy of only 0.79 ± 0.03, with the larger variance reflecting the difficulty of training. Notably, for this network size, only 6.9% of hybrid networks had an accuracy below 72%, and none failed in training. In contrast, 50% of classical networks fell below the threshold, with 4.2% failing entirely. As expected, the inclusion of quantum layers significantly improves network performance and trainability, attributed to increased informational capacity and improved optimization landscape8.

a Annotated violins of the 120-parameter hybrid network and 124-parameter classical network. The shaded blue and orange region shows the region of well-trained networks that scored better than 72% (accuracy of linear support vector machine model). The point on each violin represents the average accuracy of these well-trained networks, with error bars denoting one standard deviation from the mean. The red-shaded region represents poorly trained networks, while networks below the solid red line failed to optimize entirely. The white line is networks A and B seen in Fig. 2 and Fig. 1a, b. b Violin plot of all networks trained in this study. Each violin represents a statistical fit (kernel density estimation) of all networks with a given number of parameters, where each gray horizontal line marks the maximum accuracy achieved by an individual network during training. The line is the mean of the upper of the well-trained networks, and the shaded region is the standard deviation of that mean. c Bar plot showing the percentage of networks which failed to beat the non-probabilistic linear model (<72% accuracy, poorly trained).

We repeat this analysis for all network sizes and present the results in Fig. 3c. Across all networks with 316 parameters or fewer, we observe that the average accuracy of well-trained hybrid networks exceeds that of classical networks, while the accuracy distribution for hybrid networks remains significantly narrower than that of the classical devices. Additionally, hybrid networks are also much more likely to optimize beyond the 0.72 accuracy threshold, with 95.9% of all trained hybrid networks reaching this level, compared to the 76.3% of classical networks (the rate of poorly trained networks is shown in Fig. 3b). This further indicates that hybrid networks are much more likely to optimize successfully. Furthermore, the average accuracy of 0.85 ± 0.03 for the 120-parameter hybrid network is only matched by classical networks at 235 parameters (0.86 ± 0.04). That is, the inclusion of quantum layers consistently enables smaller hybrid networks to outperform not only similarly sized classical networks but also those that are significantly larger. The largest classical networks (590 parameters) were able to achieve an average well-trained accuracy of 0.89 ± 0.04 (for larger networks see Supplementary Note Equally Distributed Classical Networks). However, large classical networks pose significant implementation challenges and are beyond the capabilities of current photonic hardware. Finally, to ensure the benchmark architecture does not bias the classical baseline, we validate its performance by comparing it to an alternative classical architecture of equally distributed neurons. Both classical architectures achieve very similar average well-trained accuracies (see Supplementary Note Equally Distributed Classical Networks), further confirming the observed hybrid advantage.

Although Fig. 3c appears to suggest that quantum layers provide no benefit for networks with more than 316 parameters, this is likely not the case. Rather, this may be a direct consequence of the challenges associated with simulating large quantum networks. Each qumode is simulated in the Fock basis, including all Fock states up to a chosen cutoff dimension D (here D = 5, 9, 11). The maximum average number of photons in the network at any time is therefore D × M, and the total dimension of all qumodes in the quantum network is then given by DM, where M is the number of qumodes. A larger dimension allows the network to encode more information, optimize more freely, and perform more complex tasks. However, due to computational constraints large CVQNNs were simulated to a cutoff dimension of only 5, while smaller networks were simulated up to a cutoff of 11, limiting the performance of larger networks (see Supplementary Note Simulation and Cutoff Dimension and Cutoff Sweep for more details). We note, however, that the cutoff dimension is purely a simulation constraint and not a physical parameter, implying that our results are a lower bound on the performance of an ideal hybrid network. Experimentally, the Fock basis is infinite (D = ∞), with the state space and network performance being limited by the input power, detector resolution, loss, and noise.

Robustness to noise

Photonic neural networks are inherently analog systems of which precision is ultimately limited by noise39. This noise comes from a combination of thermal fluctuations, noise in the weight control currents, vibrational changes in input coupling, or detector noise. Regardless of the source, noise will ultimately determine how well a given weight in the neural network can be actuated. For convenient comparison to digital bit precision, noise is often converted to an effective number of bits (ENOB), which is determined according to the Shannon–Hartley theorem as,

Here, wmax and wmin are the respective allowed maximum and minimum values of the given weight w, and σ is the standard deviation of the noise on w. Thus, the ENOB represents the signal-to-noise ratio for an analog signal.

For a classical layer of a photonic neural network, all parameters have the range [wmin, wmax] = [−1, 1] due to optical transmission in a balanced photo detection scheme being fully in one detector, +1, or fully in the other detector, −110,40,41. In contrast, a quantum layer has both amplitude and phase parameters, where for phase [wmin, wmax] = [0, 2π] and for amplitude parameters [wmin, wmax] = [0, amax], where amax is the maximum amplitude parameter in the whole network. Thus, we can choose a σ for the noise and, from that, calculate the ENOB for the network and, by rerunning our simulations, calculate the network accuracy in the presence of noise.

Figure 4a shows exemplary curves for the network accuracy as a function of the ENOB for both the 120-parameter hybrid network (blue) and the 124-parameter classical network. For each ENOB value, the validation accuracy was calculated ten times for different randomized noise values, with the mean shown by the dark curve and the shaded region representing one standard deviation. The classical network achieves near ideal accuracy, 10% worse than ideal performance, at 5.5 bits of precision, while the hybrid network requires 6.3 bits of precision. This analysis was repeated for networks with more qumodes and layers (see Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10), showing no increase for more qumodes but a slight increase in required ENOB for networks with more layers (same maximum accuracy as networks with fewer layers). Both of these bit precision values, 5.5 and 6.3, are below the state-of-the-art 9 bits of precision that are achievable with classical photonic neurons42.

a The validation accuracy of a 120-parameter hybrid network and 124-parameter classical network as a function of the ENOB of the parameters. b The validation accuracy of a 120-parameter hybrid network with different ENOB on the different gate parameters. Kerr and interferometer gates are the most sensitive to bit precision.

Focusing on just the noise in the quantum neural network, we show how the hybrid network accuracy depends on the ENOB of the different gate parameters in Fig. 4b. To achieve near ideal accuracy, in this case 0.78, the displacement, squeezing, Kerr, and interferometer gates must have 5.0, 3.5, 6.0, and 5.0 (±0.5) bits of precision, respectively. This demonstrates that the network performance is most sensitive to the operation of \({\mathcal{U}}\), which provides the same functionality as the weights of a classical layer, and Φ, which provides the non-linearity. The relatively low required bit precision on the squeeze gate indicates that the precise magnitude of the squeezing is not important, only that the required squeezing is present (agreeing with current opinions in the field43). In our circuit, for example, the maximum squeezing parameter required is r = 0.441 with only 3.5 effective bits to reach near-ideal performance. This corresponds to a precision of δr = 0.042 or, alternatively, in dB, a maximal squeezing of VdB = −3.83 dB, with an uncertainty δVdB = 0.036 dB is required (see Supplementary Note Squeezing for details), commensurate with experimental realizations. Using similar analysis, experimentally achievable amplitude and bit precision for each of the quantum gates are summarized in Table 1 (see also Supplementary Note Implementations of Quantum Gates), showing that all operations, except Kerr, are possible with present hardware.

It is also important to consider the impact of losses and probabilistic measurement on network performance, particularly since photon losses and quantum uncertainty are unavoidable. For CV circuits, the primary consequence of loss is a reduction of the photonic space (lost photons lead to lower average photon number), leading to reduced effective squeezing and coherent state amplitude. The probabilistic nature of photon loss also means that more measurements might be required to accurately estimate the expectation value of the CVQNN output. We observe optimal CVQNN accuracy of 0.87 with 3.6 dB of squeezing, which decreases to 0.71 when an additional −1.5 dB of losses are added (resulting in a maximum squeezing of only 2.2 dB). Linearly extrapolating to current integrated CV photonic losses of −8 dB7 would correspondingly result in a lower average accuracy of only 0.28 (see Supplementary Fig. 11). Conversely, a fully integrated platform with optimized unitary design, ~2 dB of loss7,25 and a larger initial squeezing of ~8 dB, could maintain an ideal accuracy of ~0.87. It is also important to consider the imperfect measurement of quantum states and determine the number of measurements required to estimate the expectation value of the quantum circuit outputs. For exemplary network A, ~100 measurements are required to achieve peak performance (see Supplementary Fig. 7).

Discussion

Here, we have demonstrated that hybrid neural networks based on the continuous variable quantum formalism can offer tangible improvements in performance and trainability over fully classical networks of the same size, providing a pathway to increased computational complexity with fewer photonic resources. As an example, we showed that for a complex classification task, a small hybrid network with 120 trainable parameters achieved an average well-trained accuracy of 0.85 ± 0.03, comparable to a significantly larger 235-parameter classical network. Across a range of network sizes, hybrid networks consistently exhibited greater trainability and, in most cases, superior performance. Importantly, because our simulations are limited by a finite cutoff dimension, these results represent a lower bound on the true performance of an ideal hybrid network. Encouragingly, hybrid networks achieved peak performance with only 6.3 effective bits of precision, well within the capabilities of current photonic platforms42,44. We anticipate that such networks could also be trained in the presence of noise to explore the potential benefits of noise-aware training.

The hybrid networks, we propose, are compatible with integrated photonic platforms and seamlessly interface with existing photonic communication systems7,45. As summarized in Table 1, most of the required components for these networks have already been successfully implemented on-chip with sufficient bit control. For example, the displacement, squeezing and N-port interferometer have been demonstrated experimentally, and the technology to integrate these operations already exists7,28, though a practical realization remains challenging. In particular, on-chip squeezing up to 8 dB has been demonstrated using spontaneous four-wave mixing in a silicon nitride ring resonator25, well above what is required for the photonic neural networks we envision. In contrast, realizing efficient Kerr non-linearities on-chip remains a grand challenge, though promising approaches have recently emerged. These include non-linear measurement collapse46, photon addition/subtraction31, electromagnetically induced transparency35, or temporal trapping32. Additionally, future work could explore models with simplified encoding schemes, or network layers with less or more restricted (i.e., Kerr phase limited to <π/8) non-linear operations, thereby reducing network dependence on this challenging operation, and further relaxing the requirements of an experimental implementation. Beyond demonstrating the required quantum gates, the components must also be miniaturized if we are to scale CVQNNs. This is particularly critical for the squeeze gate and temporally trapped Kerr non-linearity, both of which require large resonators that would make the CVQNN layer nine times larger than similarly sized classical photonic neural networks (see Supplementary Note Implementations of Quantum Gates). Finally, our model suggests that photonic loss rates of approximately −1.5 dB are required for accurate network performance (see Supplementary Note Loss). While current CV photonic platforms have yet to achieve this threshold7, tremendous progress has been made in reducing losses, bringing this goal within reach47.

Interestingly, our hybrid networks closely resemble classical neural networks with complex-valued weights, which can be realized using coherent optical neural networks7,45. However, a key distinction is that our hybrid networks incorporate both quantum squeeze and non-linear gates in addition to complex-valued weights. This crucial addition enables hybrid networks to leverage quantum properties to improve optimization landscapes8. While here our focus has been on a classification task, the increased computational power of hybrid networks suggests potential applications beyond classification. For example, when directly integrated with existing communication platforms, hybrid networks could be used for quantum repeaters48 and photonic edge computing49. Scaling to larger and more complex neural networks is essential for addressing the challenging computational tasks often encountered in these applications. Typically, several multiplexing approaches—such as wavelength, time, and spatial division multiplexing—are employed to increase processing density, thereby increasing the number of parameters, and adding more computational power50. However, multiplexing approaches come with trade-offs, including larger footprints and more complex electrical control requirements. Here, we have shown that hybrid networks offer an alternative means of scaling network complexity and solving more difficult computational tasks with fewer parameters.

Methods

Synthetic dataset

Data was generated using the Scikit-Learn20make_classification() function. As mentioned in the text, this dataset featured 8 inputs, 4 classes, and 1000 samples. All features were informative, meaning they included non-redundant information, and each class featured 3 clusters of datapoints. On average, the clusters of datapoints were separated by an eight-dimensional vector of length 3.0 (the default is 1). 2% of samples were assigned a random class to increase difficulty. The dataset was normalized to the domain [0, 1] prior to training to simulate input transmission seen in photonic circuits41. The random state to generate this data can be provided upon request.

Classical model

The classical models (and layers) were implemented in the TensorFlow framework. ReLU non-linearities were used between each of the classical layers. All classical layers were implemented using Keras Dense layers with weight clipping beyond the domain [−1, 1]41. This simulated the range of transmission values available on photonic hardware. The size of the classical hidden layers was determined using an algorithm that, for each classical layer, matched the number of parameters in the corresponding layer of the hybrid network. In this way, both the total number of layers (circuit depth) and the total number of parameters were equivalent. The final output of the network uses a softmax non-linearity to convert the output activations to a probability distribution for classification.

Hybrid model

The hybrid models were fully implemented in the Tensorflow framework36 with the Pennylane quantum machine learning Tensorflow interface37 and the Strawberryfields Tensorflow-based simulator38. This avoided array conversions between different frameworks and enabled automated gradient calculations, GPU support, and access to machine learning functions. A Fock basis simulator was used as it can simulate the non-Gaussian gate (\(\hat{O} \sim {e}^{{\hat{n}}^{2}}\)) used in a non-linear activation function. The Fock simulator, fully implemented in Tensorflow, records the amplitudes for each of the photon number states in the Fock basis as gates are applied. The cutoff dimension D specifies the number of Fock states simulated (\(\left\vert 0\right\rangle ,\left\vert 1\right\rangle ,...,\left\vert D-1\right\rangle\)) and therefore the size of the state space. The total number of states simulated is given by DN where N is the number of qumodes.

Data begins at the input layer, which, unlike the classical network, has no non-linearity. After the input layer, there is the encoding layer into the quantum circuit. The encoding layer accepts 5 inputs for each qumode in the circuit. An amplitude and phase for the squeeze gate, an amplitude and phase for the displacement gate, and a phase for the Kerr non-linearity. The inputs into the encoding layer are scaled to the domain [0, 2π], for phase parameters, and to [0, amax], for amplitude parameters, using the following functions:

Where \({\tilde{y}}_{\{i,j\}}^{(\{{\rm{amplitude}},{\rm{phase}}\})}\) is the scaled value, Sig(y) is the sigmoid function, amax is the maximum displacement/squeezing amplitude, and y{i, j} is the output from the previous layer. amax was determined using a brute force method where amax was reduced each iteration until the state remained normalized for 100 sets of random circuit parameters. Encoding layers that are difficult to simulate classically have been shown to yield greater network performance and trainability8. To meet this criterion for the CV hybrid model, we must include a non-Gaussian operation51, in this case, a Kerr gate. Following the encoding layer, the CV quantum neural network layer is made up of N-port interferometers (\({{\mathcal{U}}}_{1},{{\mathcal{U}}}_{2}\)), squeezing gates (\({\mathcal{S}}\)), displacement gates (\({\mathcal{D}}\)), and Kerr non-linearities (Φ). The first sequence of gates, \({{\mathcal{U}}}_{2}{\mathcal{S}}{{\mathcal{U}}}_{1}\), represents the matrix multiplication step, the displacement gate \({\mathcal{D}}\) represents the bias, and the Kerr non-linearity Φ acts as the activation function15. The amplitude parameters were initialized uniformly on the domain [0, amax] and phase parameters on the domain [0, 2π]. All amplitude values were L1 regularized to improve state normalization during training. Models with 2–4 qumodes and 1–5 layers were trained. Homodyne detection in the position basis (\(\hat{x}\)) is used to measure the output value of each of the qumodes. These measurements are then input into the final classical output layer, which is used to make a classification.

Training

All networks were trained using conventional gradient descent and backpropagation. The Adam optimizer with a learning rate of η = 0.001 was used with a batch size of 32. A categorical cross-entropy loss function was used to calculate the loss, as this is a multi-class classification task. Ten to thirty hybrid networks (three different cutoff dimension values, ten for each cutoff) and 20 classical networks were trained for each network size. Training was conducted on the Digital Research Alliance of Canada’s Graham cluster.

Data availability

Data that supports the findings of this study can be found on the Borealis Queen’s University Dataverse Collection under the listing for this publication.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Zhang, W. et al. A system-on-chip microwave photonic processor solves dynamic RF interference in real time with picosecond latency. Light 13, 14 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. 11 TOPS photonic convolutional accelerator for optical neural networks. Nature 589, 44–51 (2021).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Lin, Z. et al. 120 GOPS Photonic tensor core in thin-film lithium niobate for inference and in situ training. Nat. Commun. 15, 9081 (2024).

Arrazola, J. M. et al. Quantum circuits with many photons on a programmable nanophotonic chip. Nature 591, 54–60 (2021).

Abbas, A. et al. The power of quantum neural networks. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 403–409 (2021).

Huang, C. et al. A silicon photonic-electronic neural network for fibre nonlinearity compensation. Nat. Electron. 4, 837–844 (2021).

Tait, A. N. et al. Neuromorphic photonic networks using silicon photonic weight banks. Sci. Rep. 7, 7430 (2017).

Marinis, L. D. & Andriolli, N. Photonic integrated neural network accelerators. In Photonics in Switching and Computing 2021 (2021), paper W3B.1, W3B.1 https://opg.optica.org/abstract.cfm?uri=PSC-2021-W3B.1 (Optica Publishing Group, 2021).

Prucnal, P. R. & Shastri, B. J. Neuromorphic Photonics Google-Books-ID: VbvODgAAQBAJ (CRC Press, 2017).

Tait, A. N. Silicon Photonic Neural Networks Accepted: 2018-04-26T18:46:40Z (Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, 2018) https://dataspace.princeton.edu/handle/88435/dsp01vh53wz43k.

McMahon, P. L. The physics of optical computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 5, 717–734 (2023).

Killoran, N. et al. Continuous-variable quantum neural networks. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 033063 (2019).

Choe, S. Continuous variable quantum MNIST classifiers. Preprint at arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/2204.01194 (2022).

Bangar, S., Sunny, L., Yeter-Aydeniz, K. & Siopsis, G. Experimentally realizable continuous-variable quantum neural networks. Phys. Rev. A 108, 042414 (2023).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Single-chip photonic deep neural network with forward-only training. Nat. Photon. 18, 1335–1343 (2024).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Schuld, M. & Killoran, N. Quantum machine learning in Feature Hilbert spaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 040504 (2019).

Havlíček, V. et al. Supervised learning with quantum-enhanced feature spaces. Nature 567, 209–212 (2019).

Crooks, G. E. Gradients of parameterized quantum gates using the parameter-shift rule and gate decomposition. Preprint at arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1905.13311 (2019).

Vaidya, V. D. et al. Broadband quadrature-squeezed vacuum and nonclassical photon number correlations from a nanophotonic device. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba9186 (2020).

Zhang, Y. et al. Squeezed light from a nanophotonic molecule. Nat. Commun. 12, 2233 (2021).

Lvovsky, A. I. & Raymer, M. G. Continuous-variable optical quantum-state tomography. Rev. Mod. Phys. 81, 299–332 (2009).

Paris, M. G. A. Displacement operator by beam splitter. Phys. Lett. A 217, 78–80 (1996).

Brodutch, A., Marchildon, R. & Helmy, A. S. Dynamically reconfigurable sources for arbitrary Gaussian states in integrated photonics circuits. Opt. Express 26, 17635–17648 (2018).

Lü, X.-Y., Zhang, W.-M., Ashhab, S., Wu, Y. & Nori, F. Quantum-criticality-induced strong Kerr nonlinearities in optomechanical systems. Sci. Rep. 3, 2943 (2013).

Basani, J. R., Niu, M. Y. & Waks, E. Universal logical quantum photonic neural network processor via cavity-assisted interactions. npj Quantum Inf. 11, 142 (2025).

Bartley, T. J. & Walmsley, I. A. Directly comparing entanglement-enhancing non-Gaussian operations. N. J. Phys. 17, 023038 (2015).

Yanagimoto, R., Ng, E., Jankowski, M., Mabuchi, H. & Hamerly, R. Temporal trapping: a route to strong coupling and deterministic optical quantum computation. Optica 9, 1289–1296 (2022).

Steinbrecher, G. R., Olson, J. P., Englund, D. & Carolan, J. Quantum optical neural networks. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 1–9 (2019).

Ewaniuk, J., Carolan, J., Shastri, B. J. & Rotenberg, N. Realistic quantum photonic neural networks. Adv. Quantum Technol. 6, 2200125 (2023).

Liu, Z.-Y. et al. Large cross-phase modulations at the few-photon level. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 203601 (2016).

Abadi, M. et al. TensorFlow: a system for large-scale machine learning. Preprint at arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1605.08695 (2016).

Bergholm, V. et al. PennyLane: automatic differentiation of hybrid quantum-classical computations. Preprint at arXiv http://arxiv.org/abs/1811.04968 (2022).

Killoran, N. et al. Strawberry fields: a software platform for photonic quantum computing. Quantum 3, 129 (2019).

de Lima, T. F. et al. Noise analysis of photonic modulator neurons. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 26, 1–9 (2020).

Tait, A. N., Nahmias, M. A., Shastri, B. J. & Prucnal, P. R. Broadcast and weight: an integrated network for scalable photonic spike processing. J. Lightwave Technol. 32, 4029–4041 (2014).

Bangari, V. et al. Digital electronics and analog photonics for convolutional neural networks (DEAP-CNNs). IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. PP, 1–1 (2019).

Zhang, W. et al. Silicon microring synapses enable photonic deep learning beyond 9-bit precision. Optica 9, 579–584 (2022).

Pfister, O. Continuous-variable quantum computing in the quantum optical frequency comb. J. Phys. B 53, 012001 (2019).

Ashtiani, F., Geers, A. J. & Aflatouni, F. An on-chip photonic deep neural network for image classification. Nature 606, 501–506 (2022).

Martin, V. et al. Quantum technologies in the telecommunications industry. EPJ Quantum Technol. 8, 19 (2021).

Marshall, K., Pooser, R., Siopsis, G. & Weedbrook, C. Repeat-until-success cubic phase gate for universal continuous-variable quantum computation. Phys. Rev. A 91, 032321 (2015).

PsiQuantum team. A manufacturable platform for photonic quantum computing. Nature 641, 876–883 (2025).

Azuma, K. et al. Quantum repeaters: from quantum networks to the quantum internet. Rev. Mod. Phys. 95, 045006 (2023).

Sludds, A. et al. Delocalized photonic deep learning on the internet’s edge. Science 378, 270–276 (2022).

Bai, Y. et al. Photonic multiplexing techniques for neuromorphic computing. Nanophotonics 12, 795–817 (2023).

Kok, P. & Lovett, B. W. Introduction to Optical Quantum Information Processing 1 edn. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/identifier/9781139193658/type/book (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Acknowledgements

All authors acknowledge the support of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC), Digital Research Alliance of Canada (DRAC), and Queen’s University. TA and BJS acknowledge the support of the Vector Institute. BJS is supported by the Canada Research Chairs program. NR and BJS acknowledge the support of the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was originally conceived by T.A. and B.J.S. A.H. provided initial code and, with S.B., a useful discussion. T.A. performed all simulations to generate data and figures. T.A. prepared the original paper, with the help of N.R., which was then edited by B.J.S. and N.R. Research led by B.J.S. and N.R.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Austin, T., Bilodeau, S., Hayman, A. et al. Hybrid quantum-classical photonic neural networks. npj Unconv. Comput. 2, 29 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00045-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44335-025-00045-1