Abstract

Water adsorption in nanoporous carbons is a complex process due to the interplay between pore structure and surface chemistry. Sending an ultrasound wave through a nanoporous sample allows for the retrieval of a wealth of information, including the properties and spatial distribution of nanoconfined fluid. We used a novel adsorption-ultrasonic experimental setup to analyze the characteristics of ultrasound propagation through a xerogel sample while measuring its sorption isotherm by controlling relative humidity. The adsorption followed a type V isotherm, characteristic of weakly interacting carbon micropores and mesopores. Analysis of the elastic moduli revealed that confined water in mesopores deviates from bulk-like behavior. Additionally, the increase in ultrasonic attenuation during micropore filling suggested spatial heterogeneity in the water-filled pore space. This study demonstrates the utilization of non-destructive ultrasonic testing to probe both the fluid adsorption mechanism and the properties of an adsorbed phase in nanoporous materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acoustic studies of vapor-sorbing porous materials go back at least four decades, to the experiments by Murphy, who investigated the attenuation of low-frequency acoustic waves (300 Hz to 14 kHz) as a function of water saturation for Massilon sandstone and Vycor glass samples1. Subsequent work focused on various aspects of the complex behavior exhibited by the fluid-porous medium composite. For instance, Warner and Beamish2 studied ultrasound propagation in a Vycor glass sample during nitrogen adsorption at 77 K, proposing ultrasound as an alternative tool for measuring adsorption isotherms. Page et al.3,4 used Vycor glass to measure the propagation speed and attenuation of an ultrasound wave during adsorption and desorption of n-hexane, to explore pore-filling and pore-emptying mechanisms, and relate them to optical measurements on the same Vycor material. More recently, Schappert and Pelster published a series of works, reporting ultrasound propagation in Vycor glass in the course of adsorption/desorption of various vapors at ambient and cryogenic temperatures5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Combined adsorption-acoustic experiments were also used to study the change in mechanical properties caused by water sorption in real rock samples, including sandstone, limestone, shale, and granite, along with model glass-bead based porous medium12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20. Lastly, the authors of this paper obtained a wealth of information by combining water sorption with ultrasound propagation for a diverse set of samples represented by sandstone21, Vycor glass22, and macroporous polymer composites23. This body of work has brought attention to the behavior of acoustic waves during vapor sorption in nanoporous materials, since fluids in nanopores show many unique properties24,25,26, some of which can be retrieved from the ultrasound-based measurements. Vycor glass is the only nanoporous material that has been studied by combined adsorption-ultrasonics in great detail. This is due to its availability in the form of monolithic samples, its accessible and well-defined pore space (7–8-nm diameter), and its hydrophilic pore wall surface.

Similar to Vycor, nanoporous carbons show a complex adsorption behavior that has been widely studied to understand the mechanism and governing factors in order to utilize these carbons in materials applications27, such as adsorption and separation, energy storage, catalysis, hydrogen storage, and environmental remediation28,29,30. The adsorption mechanism and the characteristics of isotherms depend on the properties of the vapor being adsorbed and also vary between the materials with different pore structures and surface chemistries, which are made available by modern synthesis methods. Indeed, nowadays nanoporous carbon materials with unique physical and chemical properties can be prepared, including well-controlled porous structure, high specific surface areas, electronic and ionic conductivity, and enhanced mass transport and diffusion.

For water vapor, the sorption isotherms at low to intermediate humidities are S-shaped with a hysteresis loop following type V classification, corresponding to relatively weak adsorbent-adsorbate interactions31. To unveil the detailed mechanisms of water adsorption on carbons, additional experimental techniques are widely utilized. For instance, Iiyama et al.32 and Kaneko et al.33, based on X-ray diffraction measurements and electron radial distribution function analysis, reported the formation of an ordered assembly structure of water adsorbed in carbon micropores. Bahadur et al.34 studied the kinetics of water adsorption in ultramicroporous carbon using in-situ small-angle neutron scattering, confirming that the adsorption of water occurs via cluster formation and showing the variations of geometry and the concentration of the clusters over the adsorption process. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies conducted by Wang et al.35 proposed a two-step filling mechanism from the measured variation of spin-lattice relaxation time. To our knowledge, there have not been attempts to complement water adsorption experiments in nanoporous carbons with ultrasound propagation measurements.

Here, we used the combined ultrasonic pulse transmission–vapor adsorption technique to investigate the characteristics of ultrasound wave propagation through water-sorbing carbon xerogel, a synthetic nanoporous carbon with tunable material properties, available as a monolithic sample. The xerogel in this study had a bimodal pore size distribution (PSD), comprised of micropores and mesopores, giving rise to two-step pore filling during water adsorption, as shown previously36. The unique characteristics of ultrasonic wave propagation allowed us to shed light on the mechanism of water adsorption, associated adsorption-induced sample deformation, and the bulk modulus of the water confined in nanopores.

Results

Xerogel material properties

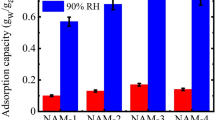

Figure 1a shows a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image and a schematic depiction of the carbon xerogel microstructure, which consists of a network of interconnected particles with an average size, dpart of 8.1 nm. The cavities in the pore network between the particles fall within the range of the mesopores (~8 nm), but there are also intraparticle micropores (~1 nm). These micropores are formed during sample carbonization, where the organic polymer precursor undergoes thermal decomposition, leading to the formation of small, interconnected voids inside the resulting carbon particles. The presence of both micropores and mesopores in the sample can be seen in the N2 sorption isotherm (Fig. 1b), which is clearly divided into two regions. The micropore region corresponds to a steep rise at low relative pressure p/p0 just above zero, and capillary condensation in mesopores corresponds to a steep rise at p/p0 ~0.6. Figure 1c, d show calculated PSDs for mesopores and micropores, respectively, and the material properties of the xerogel used in this study are listed in Table 1.

a Monolithic synthetic carbon xerogel sample used in this study, its SEM image, and a schematic depiction of its microstructure. b Nitrogen sorption isotherm at 77 K. c Differential and cumulative mesopore size distributions obtained from a non-local DFT (NLDFT) Kernel for nitrogen on carbon with cylindrical pore geometry, and d differential and cumulative micropore size distributions obtained using a combination of two NLDFT models from CO2 and N2 sorption measurements (CO2 at 273 K in carbon and N2 at 77 K on carbon slit pores) using the “NLDFT advanced PSD” tool of Microactive by Micromeritics, GA, USA. The observed peak of the differential micropore volume at ~0.5 nm is a typical artifact that could result from the monolayer step in the NLDFT approach, or other imperfections of the DFT methods79,80.

Equilibration of the xerogel sample at different vapor saturations

Due to the high specific surface area and large sample pore volume, the equilibration between the sample and its water vapor environment was slow. To determine the equilibration time, a combination of ultrasonic and gravimetric measurements was performed. Thus, while we are primarily interested in equilibrium properties, our measurements allowed us to evaluate adsorption kinetics as well. Figure 2a shows the variation of the measured travel time of the longitudinal wave with the exposure time for the sample that started at ambient relative humidity (RH) of 48% and then was exposed to 12% RH. Based on the variation of the travel time, the estimated equilibration time at 12% RH was ~60 hrs. After the equilibration, the sample was exposed to progressively higher RH in steps. Figure 2b shows the variation of the travel time with the exposure time at each RH level, ranging from 30% to 88%. The starting point of each of curves is the end point obtained at the previous RH. Notably, when RH is raised to 93%, the evolution in travel time does not show a monotonic behavior. Instead, as illustrated in Fig. 2c, there is an increase in travel time during the first ~150 hrs of water adsorption, followed by a relatively sharp drop in travel time nearly to its initial level, and then the travel time remains constant after 200 hrs. Contrary to the ultrasound measurement, the mass measurement does not indicate an equilibration of the sample with water vapor, and even after 15 days of exposure at 93% RH the sample mass continues to increase (Fig. 2c). Figure 2d shows the corresponding percent change in the longitudinal wave speed, along with the estimated sample density and longitudinal modulus, as a function of time after changing the RH from 88% to 93%. In agreement with the trends in travel speed and mass gain, the relative change in the ultrasound speed is much smaller than the change in the sample density. After 360 hours (15 days), the target humidity was adjusted to 98% RH, and after additional ~100 hrs of exposure, both travel time and mass reached a plateau (Fig. 2c). At this point, the adsorption experiment was deemed completed, and the desorption route was initiated.

Variation of the travel time of the longitudinal wave with the exposure time of the sample a after changing RH from 48% to 12% and b to each RH level from 30% to 88%. c Variation of the travel time of the longitudinal wave and the sample mass with the exposure time of the sample at 93% RH (filled markers) and 98% RH (empty markers). d % Change of longitudinal speed (vL), bulk density (ρb) and the longitudinal modulus (M) with the exposure time of the sample at 93% RH. Note: the base time, t = 0 is taken when the sample is exposed to 93% RH after equilibration at 88% RH. e Cracks observed along the axial direction of the sister sample at (I) 84% RH and (II) 77% RH during desorption (similar cracks were observed on the sample used for ultrasonic measurements after the experiment was completed). f Growth of additional longitudinal peak in the waveforms measured over the time at 84% RH.

During desorption, the sample cracking along both axial and circumferential directions was visually noted at 84% RH, and during further desorption, partial healing of the sample crack was observed at 77% RH (Fig. 2e). This sample cracking was also detected by the ultrasound measurement from the growth of an additional longitudinal peak in the waveforms obtained at 84% RH as shown in Fig. 2f (day 2). The origin of the additional peak may be due to creating an additional path for wave propagation or reflection of the waveform at the crack surface of the sample. Based on the time delay between the peaks P1 and P2, the estimated additional path length for the second peak is ~1.52 mm. Therefore, the second peak may arise due to the wave reflection at circumferential cracks, which are ~1 mm apart. The shear peak disappeared after the sample cracking. The observed loss of shear wave amplitude can be due to the discontinuity of the ultrasonic pathway for the shear waves at the crack interface. However, the measurements were continued with the cracked sample.

Water sorption isotherms

The water sorption isotherm measured for the monolithic xerogel sample by the sorption-ultrasonic setup is shown in Fig. 3a, along with the isotherm obtained for the granulated xerogel sample with a commercial water sorption balance, as described in the “Material characterization” section. Below 70% RH, both isotherms show type V character31 that corresponds to water adsorption on a weakly interacting nanoporous material. Thus, water vapor condenses in the micropores first, and this process continues with the increase of RH until most of the micropore volume is filled at ~70% RH, and the isotherms start to level off. When RH exceeds 90%, mesopores begin to fill, i.e., water is adsorbed in the interparticle spaces. Both monolithic and granulated samples do not reach the full saturation, and the observed discrepancy between the maximum saturation levels for each sample will be discussed in the “Water adsorption by nanoporous carbon” section. Desorption occurs following a type H1 hysteresis loop,31 which arises due to water-carbon interactions coupling with surface heterogeneity and confined geometry effects. At low RH, isotherm loop opening is observed for both granulated and monolithic samples. Figure 3b shows the sample saturation with water, defined as percentage of volume of water adsorbed with respect to both the total pore volume, \({V}_{{\rm{pores}}}\) (left axis) and total micropore volume, \({V}_{{\rm{micropore}}}\) (right axis). Sample saturation with respect to the micropore volume reaches 100% at the RH when the mesopore volume filling begins. However, the total sample saturation reaches only ~78% of the theoretical pore volume present, despite the sample mass change reaching a plateau at 98% RH (Fig. 2c), indicating that the mesopores are not filled fully on the timescale of our experiment.

a Sorption isotherm measured using the custom made setup for the monolithic sample (green) and sorption isotherm measured using a commercial water sorption balance for the granulated sample (brown). Error bars represent the errors associated with the mass measurements by the balance. The size of error bars in the y axis is 0.04% and they are smaller than the markers. b Estimated % sample saturation based on the ratio of the adsorbed water volume to the total pore volume (left scale) and to the micropore volume (right scale) of the monolithic sample. Solid lines with filled markers: adsorption, and dashed lines with empty markers: desorption.

Elastic properties of the xerogel-water composite

In our experiments, it was necessary to record both longitudinal and shear waves at each point of the adsorption isotherm using the same set of transducers. We could not swap longitudinal and shear transducers during measurements because this would have affected their alignment, introducing time and amplitude artifacts in the measured waveforms. To determine which combination of transducers was the best at discriminating between longitudinal and shear waves in a single measurement, we explored the use of four different transducer combinations, LL, SS, LS, and SL, as shown in Fig. 4a. In these two-letter combinations (L is for longitudinal and S is for shear), the first letter in a sequence corresponds to the transmitter and second to the receiver. We found that the SL transducer combination provided the best discrimination, which is consistent with the conclusion by Yurikov et al.37, and so this combination was used to measure the waveforms in water sorption experiments. The waveforms recorded after reaching an equilibrium at each RH level are shown in Fig. 4b. The travel times for both longitudinal and shear waves were calculated relative to the reference waveform (waveform measured for transducer-couplant-transducer system without sample) (Fig. 7c), and those travel times were used to calculate the respective wave speeds.

a Waveforms measured using different XY transducer combinations, where X is the transmitter and Y is the receiver, representing L and S, longitudinal and shear transducers, respectively. b Waveforms measured using SL combination at each RH during the adsorption route. c Variations in longitudinal and shear wave speeds during water adsorption (solid lines with filled markers) and desorption (dashed line with empty markers), where the error bars represent the errors associated with the measurements of the sample length and the travel time. The measurements at 0% RH were performed in a vacuum (2 Torr). d Moduli obtained during water adsorption (solid lines with filled markers) and desorption (dashed line with empty markers). Attenuation of the longitudinal wave propagation through the sample during water adsorption is shown as a function of e RH and f sample saturation.

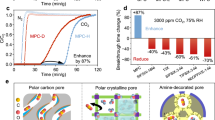

The variations of both longitudinal, vL and shear, vS wave speeds with RH are shown in Fig. 4c. During adsorption, both longitudinal and shear waves exhibit a speed decrease, consisting of two distinct regions. In the lower RH region (12% ≤ RH ≤ 84%), vL and vS decrease nearly linearly by ~58 and ~48 m s−1, respectively, over a 72% ΔRH span. Then in the range of 84% ≤ RH ≤ 93%, both vL and vS follow a much steeper decrease, ~41 and ~280 m s−1 over a 14% ΔRH span, and reach a plateau at 98% RH. The initial region in the wave speed plot (Fig. 4c) corresponds to the initial region in the sorption isotherm (Fig. 3a), where water is adsorbed mainly in micropores while the mesopores remain empty. Therefore, the initial decrease of the wave speeds at lower RH is related to the micropore filling. A steeper decrease in the speed is seen in the second region above 84% RH, as the micropore filling is completed and adsorption takes place in mesopores. When the desorption route is started, the observed sudden drop of longitudinal speed and the complete loss of the shear signal are likely an indication of sample cracking, which was also visually confirmed.

The longitudinal, M and shear, G moduli, calculated from Eqs. (4) and (5) (described in “Ultrasonic measurements” section) using the respective wave speeds and the materials bulk density adjusted for the adsorbed water mass gain, are shown in Fig. 4d, using the same vertical span. Both M and G show a gradual, slight increase of 5.2% and 3.2%, respectively, between 12% and 88% RH. Afterwards, at higher RH between 88% and 98%, M follows a steep increase by ~55%, mimicking the water adsorption, while G shows only a slight increase by ~6%.

The amplitude of measured waveforms varies significantly with the change in RH (Fig. 4b), and this is attributed to the ultrasonic attenuation. Ultrasonic attenuation, a measure of the acoustic energy loss per one wave period during the wave propagation through a medium, can be quantified by the inverse of the quality factor (Q−1). In this study, the spectral ratio method38, which compares the amplitudes of the waveform in the frequency domain with the low-loss reference waveform, was used to determine the ultrasonic attenuation as a function of water saturation. Figure 4e shows the measured change of attenuation (ΔQ−1) of the longitudinal wave during the adsorption process with respect to the attenuation of the waveform measured at 12% RH (a reference waveform). Since the sample cracked on desorption, and the shape of the waveform changed, the attenuation data is not reported for the desorption process. At a low RH ( < 30%) the attenuation remains almost constant, but it continuously increases over the range 30% < RH < 88%, exhibiting a sharp peak at 88% < RH < 98%. Figure 4f shows the attenuation as a function of the sample saturation.

Discussion

Based on the production process, and chemical and physical post-treatments, carbon materials own their surface chemistry to various functional groups, such as surface oxides, which promote the adsorption of water39,40. The oxygen atoms in the surface oxide groups are the primary adsorption centers where the water molecules attach via hydrogen bonds. The concentration of the surface functional groups correlates with the adsorption capacity41,42,43. At low pressures, water adsorption in micropores is initiated by attaching water molecules to the functional groups, and as the pressure increases, further water adsorption occurs on top of the adsorbed water molecules, growing water clusters near the functional groups. Indeed, for the range of 12% < RH < 60%, the measured isotherm follows type III character, describing the water clustering process. As shown in Fig. 3a, water uptake by the granulated sample is slightly higher (by ~3%) than that of the monolithic sample at RH < 70%. This higher initial uptake on the granulated sample could be because it was initially degassed at 300 °C, and only N2 was used as the carrier gas in the commercial water adsorption balance. The monolithic xerogel sample was not degassed by heating and hence may have contained a small amount of adsorbed water. Additionally, during the experiment, it was exposed to water vapor in ambient air, possibly resulting in the presence of co-adsorbed CO2, reducing the micropore volume accessible for water filling. Hence, the maximum volume adsorbed in the micropore range of the isotherm obtained on the monolithic sample is below the value measured on the granulated sample. However, at the highest RH, the observed discrepancy of maximum saturation (~80% vs ~60%) of monolithic and granulated samples is the other way around. This difference is primarily due to the monolithic sample being exposed to a higher RH level (98%) compared to the maximum exposure of the granulated sample, which was at 95% RH. Additionally, the expected water saturation may deviate from the value calculated using the pore volume measured from N2 isotherms due to the difference in packing of H2O and N2 molecules in the pore space. Adsorption of other molecules from the atmosphere, such as CO2, may also lower the saturation level below 100%. During water adsorption, the surface chemistry of the pore walls can be irreversibly modified by the water interaction with the surface functional groups (chemisorption), and it may cause the isotherm loop opening observed at low RH. Due to the differences in the maximum RH values (95% vs 98%) during the adsorption experiments on granulated and monolithic samples, a slight mismatch is observed between the desorption portions of the two isotherms.

Sample cracking observed in our experiments during water desorption indicates the occurrence of a plastic deformation in the carbon xerogel, as it takes up and releases water. Notably, although the water sorption isotherm was not affected during cracking, the shape, amplitude, and speed of ultrasonic waveforms changed significantly. Adsorption-induced deformation, i.e., structural change of the solid adsorbent during the fluid adsorption, is a widely studied effect in nanoporous materials44. During adsorption, fluid exerts pressure on the solid by varying surface stress or a change in the solvation pressure inside the pores, and this pressure leads to the deformation of the solid phase. Balzer et al. reported contraction of microporous synthetic carbons during the initial adsorption of N2, Ar, CO2, and H2O in micropores, followed by expansion as the micropores became fully filled45. The magnitude of contraction and expansion in that study depended on the adsorbate, with water showing a significant contraction. At the initial water adsorption in micropores at low pressures, the formation of a water cluster bridge between the pore walls leads to the material contraction, while the material expansion takes place with the further increase of relative pressure. This phenomenon of nonmonotonic deformation can be further explained by the positive and negative solvation pressure determined by the pore size and molecular packing. Typically, the deformation of porous carbons and glasses due to adsorption is elastic, and the measured strain is in the range of 10−3−10−4 6,46,47,48. However, cracking can occur when local strains exceed the fracture limit, similar to other nanostructured carbon materials–fractal soot particles, which restructure upon vapor condensation. Soot particles are aggregates of primary carbon spherules chemically fused together by carbon necks, and their lacey fractal morphology becomes compact due to the capillary forces exerted by liquid condensates49 that induce the fracturing of carbon necks. In a recent study50, using our discrete element method (DEM) model51 we have shown that that shear stress is much higher (by three orders) than tensile stress due to a combination of torques and levers in a fractal aggregate, and most of that stress is focused on a few necks, resulting in their fracture. A similar process may have occurred in the xerogel sample, producing a single long crack.

The elastic moduli of the composite xerogel-water sample can be used to retrieve the modulus of confined water, given known values of the moduli of the solid carbon and the porous sample. The poroelastic theories proposed by Gassmann52,53 and Biot54,55 describe the elastic properties of the fluid-saturated porous medium and their dependence on the elasticity of the pore fluid. The Gassmann equation relates the effective bulk modulus of the fluid-saturated porous medium to its porosity ϕ and the bulk moduli of the dry porous medium K0, solid phase Ks, and the fluid Kf as,

where the Biot-Willis coefficient \(\alpha =1-\frac{{K}_{0}}{{K}_{{\rm{s}}}}\). This relation clearly reflects the effect of the elastic properties of the fluid on the effective elastic properties of the fluid-filled porous medium. Previous studies utilized the Gassmann equation to explore the elastic properties of fluids confined in nanoporous media and observed deviation of their elastic properties from those in the bulk4,22,25,56,57. The deviation is due to the interplay between the solid-fluid interactions and the pore structure, including the size, shape, and connectivity of the pores in the material. These experimental observations are backed by recent density functional theory calculations and molecular simulations24,26. However, since the Gassmann equation was derived for fully saturated porous media, the fluid bulk modulus Kf parameter in the equation must be redefined for the partially saturated porous media.

For a porous medium saturated with a mixture of two fluids distributed uniformly within the pore space, where one of the fluids could be air or vapor, the mixture can be considered as a single fluid with an effective bulk modulus Kf given by,

where S1 and S2 are the volume fractions of each fluid with bulk moduli Kf1 and Kf2, respectively. The combination of Eqs. (1) and (2) are defined as the Gassmann-Wood (GW) limit58.

However, if the characteristic size of the pore clusters saturated with two fluids is much larger than the hydraulic diffusion length, the equilibration of fluid pressure between clusters of pores with different levels of saturation is not reached within one time period of the wave. This saturation is known as the patchy saturation where clusters of pores are fully saturated by fluid 1 while the rest of pores are saturated by fluid 2 (Fig. 5a). The bulk moduli, \({K}_{{\rm{G}}}^{1}\) and \({K}_{{\rm{G}}}^{2}\) of the pore clusters saturated with each fluid can be obtained from the Gassmann equation using the respective fluid bulk moduli, Kf1 and Kf2. The effective bulk modulus, KGH of the medium represented by a mixture of pore clusters can be expressed by the volume fraction-weighted longitudinal moduli of each pore cluster, as given by Hill theorem59.

This relation is known as Gassmann-Hill (GH) limit, and it considers the shear modulus to be independent of the saturating fluid and equal to the shear modulus of the dry porous medium, G0. Both GW and GH approximations allow the expression of the dependence of material’s effective bulk modulus on the fluid saturation of the sample60. Figure 5b shows the effective bulk modulus of carbon xerogel plotted against its water saturation as obtained from ultrasonic measurements (indigo) and as estimated using GH (teal) and GW (maroon) approximations. A point obtained by the Gassmann equation, assuming a 100% saturation (magenta) is also shown. To obtain these estimations, we used the bulk modulus of the dry sample measured in a vacuum K0 = 2.11 GPa, bulk modulus of solid phase Ks = 48.2 GPa estimated from the Kuster and Toksöz (KT) effective medium theory61, water bulk modulus at 20 °C KW = 2.2 GPa, and the bulk modulus of water vapor Kv = 2.2 kPa62. Since Kv ≪ KW, the effective fluid bulk modulus in the pores, Kf defined by Eq. (2) is almost equal to the vapor bulk modulus, Kv, until the water saturation, S1 reaches the limit of S1 = 1 − Kv/KW, and then it rises sharply to Kf = KW when S1 ≃ 160. This variation of Kf with the water saturation reflects the variation in the GW limit as shown in Fig. 5b.

a Schematic illustration of the spatial distribution of the fluid-filled pores during the uniform saturation and the patchy saturation. b The effective bulk modulus of the xerogel sample, obtained from ultrasonic measurements and estimated from Gassmann, GW, and GH approximations (indigo dashed line with an empty marker: extrapolation of experimental data to find the bulk modulus at full saturation).

Experimentally measured effective bulk modulus shows a good agreement with GH approximation, where the bulk modulus increases with the water saturation. This agreement confirms the spatial heterogeneity of the water-filled pore space in xerogel that leads to a patchy saturation. In the case of Kv ≪ KW ≪ Ks, the GH limit is linear with water saturation, S1 as given by \({K}_{{\rm{GH}}}={K}_{0}+\frac{{\alpha }^{2}}{\phi }({S}_{1}({K}_{{\rm{W}}}-{K}_{{\rm{v}}})+{K}_{{\rm{v}}})\)60. Therefore, we used the linear approximation to extrapolate the experimental data as shown in Fig. 5b (indigo dashed line with empty markers) and obtained an estimation for the bulk modulus of the fully saturated xerogel sample as KG = 5.91 GPa. Then, using this value we estimated the bulk modulus of water, KW in mesopores at 100% saturation by the Gassmann relation (Eq. (1)). Since here we consider the water filled in mesopores, we used mesopore porosity, ϕ = 0.59 and effective bulk modulus of the solid phase including the water-filled micropores as Ks = 11.27 GPa. Ks was calculated from the KT effective medium theory for cylindrical pore geometry using K0 = 2.39 GPa and G0 = 1.84 GPa (bulk modulus and shear modulus of the xerogel sample with completely filled micropores). The estimated KW reaches 4.08 GPa at full saturation, which is 85% higher than that of bulk water (2.2 GPa). While the linear extrapolation used to obtain this value should be used for quantitative predictions with caution, this result is consistent with the reported positive deviation of bulk modulus of water (KW = 3.85 GPa) confined in nanoporous Vycor glass22. The deviation of the bulk modulus of adsorbed water from that of bulk water can be due to the interactions between the water molecules and the carbon surface. Previous molecular simulation studies on the bulk modulus of liquid argon63, nitrogen25 confined in silica nanopores, and methane64 confined in carbon nanopores reveal that the deviation of the elastic properties of nanoconfined fluids from those of bulk fluids is determined by the nanopore size. Specifically, these studies show that, at a given pressure, the bulk modulus of these fluids increases linearly with the reciprocal pore size. Here, we obtained ~6% higher water bulk modulus in carbon mesopores (~8.3 nm pore size) compared to that of mesoporous Vycor glass (~7.5 nm pore size). Although we estimated the water bulk modulus specifically in the mesopores of the xerogel, the presence of water confined in micropores with typically higher bulk modulus may contribute to a higher estimated bulk modulus in the mesopores in carbon xerogel vs Vycor glass. The nature of the solid–fluid interaction at the adsorption interface also affects the deviation in the elastic properties of nanoconfined fluids65,66. Therefore, the difference in the measured water bulk modulus between xerogel and Vycor may arise from the distinct water interactions with each material. Finally, the discrepancy can be due to the uncertainties associated with the calculation of the bulk modulus of water in carbon xerogel.

KT effective medium theory is typically used to estimate the effective bulk, K and shear, G moduli of a porous medium, using the porosity, bulk, Ks, and shear, Gs moduli of the solid phase, and the pore geometry. Here we follow the opposite path, relying on KT effective medium theory derived for cylindrical pore geometry to calculate Ks using experimentally measured elastic properties of dry porous material, M0 and G0, and the porosity, ϕ (for more details, see refs. 22,57). Since the estimated Ks can deviate from the actual value, an estimation of the effect of Ks on the calculated materials effective bulk modulus and the water bulk modulus is important. Previous studies have reported the dependence of the bulk modulus of amorphous carbons on the hybridization and the materials density, and the reported bulk moduli range from 80 to 516 GPa over the density variation from 2.4 to 3.3 g/cm367. Since the pores in xerogel have a disordered structure, the pore geometry used for the KT effective medium theory will affect the estimated Ks68,69, and it will reflect in the estimated water bulk modulus. We estimated Ks for cylindrical pores (Ks = 11.27 GPa) and spherical pores (Ks = 9.11 GPa), and we observed that a relative uncertainty in Ks by ~21% results in a ~12% uncertainty in the calculated water bulk modulus KW.

The presence of a bimodal PSD in nanoporous carbons, consisting of micropores and mesopores, typically produces a characteristic two-step water sorption isotherm with initial micropore filling at lower pressures and mesopore filling at high pressures36. In this study, a clear transition from micropore filling to mesopore filling is reflected not only in the water sorption isotherm but also in the variations of wave speeds, ultrasonic attenuation, and elastic moduli. Figure 6 shows the % change of mass density and elastic properties relative to their values at 12% RH expressed as a function of RH and % saturation during adsorption. In the RH range from 12% to 88%, density increases by 12% while vL and vS decrease by 3.3% and 4.3%, respectively. From 12% RH to 30% RH (between the first two data points), both longitudinal and shear moduli increase relatively sharply by ~2.5%. This material stiffening can be related to the pre-stress arising during the material contraction at initial micropore filling45. The material contraction can be viewed as a porosity reduction, which leads to an increase in material stiffness. After that, from 30% RH to 88% RH, the shear modulus remains constant while the bulk modulus increases steadily by another ~4.7%, and this is an indication of patchy saturation of water with complete micropore filling. At higher RH (from 88% to 98%), the sample gains a significant amount of water with the mesopore filling, and the density increases steeply by 65%. With this steep density increase, vS decreases by 17%, and therefore the shear modulus, G remains constant while the longitudinal and bulk moduli follow a sharp increase, further confirming the patchy saturation.

Ultrasonic attenuation in porous materials primarily results from the acoustic impedance mismatch between the solid matrix and the fluid-filled pore space. The heterogeneity of the fluid-filled pore space, such as variations in pore saturation or patchy fluid distribution, creates additional impedance mismatches. The greater the heterogeneity in the pore structure or the degree of fluid saturation variation, the more pronounced the impedance mismatch and, consequently, the higher the attenuation. At low RH levels (<30%), water cluster formation occurs uniformly within both micropores and mesopores. As a result, the measured ultrasonic attenuation remains relatively constant in this region. From 30% RH to 88% RH, the micropores become fully saturated with water, while the mesopores remain empty, creating a spatial heterogeneity in the water-filled pore space. This heterogeneity of the water-filled pore space leads to the observed increase of the attenuation in the RH region from 30% to 88%. The attenuation peak at 93% RH reflects the highest heterogeneity of the water-filled pore space, where almost all the micropore space is completely filled, and the mesopores begin to fill. The decrease of attenuation from 93% RH to 98% RH reflects the transition of heterogeneous filling to homogeneous filling as the sample reaches full saturation with fully filled micropores and mostly filled mesopores. Note that in order to make the discussion more quantitative, more RH points are needed in the range 90-100%, so that the peak is represented by more than a single point. Also, the attenuation measured at 93% RH provides the attenuation of a non-equilibrated system as discussed in Fig. 2c, and further equilibration will lead to changes in the attenuation peak. Previous ultrasonic studies of hexane4 and water22 adsorption on Vycor glass related the sharp attenuation peak to the capillary condensation. In mesoporous Vycor glass, both hexane and water adsorption occur uniformly at lower vapor saturation until the capillary condensation starts to fill the pores completely. At the onset of the capillary condensation, adsorption becomes non-uniform as the sample contains both completely and partially filled pores, and later it becomes uniform again with the full saturation of all the pore volume. The attenuation is attributed to the relaxation of fluid pressure, causing viscous dissipation as the wave propagates through the sample with different levels of liquid saturation. Hence, our study demonstrates the utilization of acoustic attenuation measurements to evaluate the spatial distribution of the water-filled pore space within the overall sample volume.

In this study, we relied on the ultrasonic wave propagation characteristics, such as wave speed and amplitude, to retrieve the sample elastic modulus and wave attenuation, gaining a deeper understanding of the water adsorption and filling mechanism of nanoporous carbon xerogel. To achieve this, the ultrasonic wave speeds were measured concurrently with water sorption isotherm using a novel adsorption-ultrasonic experimental setup. Overall, water sorption follows a type V isotherm with a type H1 hysteresis loop. The observed distinct trends in the variation of wave speeds and elastic moduli demonstrate a clear correlation with the density variation obtained from the adsorption isotherm. In the low RH region, sorption follows a type III isotherm corresponding to the clustering of water molecules and micropore filling. When the micropores are filled, water continues to adsorb in mesopores, suggesting a two-step filling mechanism. The observed variation in acoustic attenuation with the increase in water saturation reflects the transformation from spatially heterogeneous towards spatially homogeneous fluid-filled pore space, as the adsorption proceeds from micropore to mesopore filling. Using the GH relation, we estimated the bulk moduli of water confined in micropores and mesopores that reflect the configuration of water molecules inside those pores and the interaction of water molecules with the carbon surface. Overall, water adsorption is governed by both the surface chemistry and the PSD of the carbon xerogel. Our study thus demonstrates the utilization of ultrasonic testing as a non-destructive tool for probing the fluid adsorption mechanism in nanoporous media, and overall characterization of porous materials using acoustical techniques70. Our future research will focus on the application of ultrasonic-adsorption techniques to granular adsorbents, such as binderless zeolite. The elastic properties of these materials are heavily dependent on their granular structure, which can be altered by fluid adsorption. Consequently, the elastic properties of both the solid and fluid phases in these materials are sensitive to the adsorption process, making them difficult to assess using conventional mechanical testing methods. Ultrasonic techniques provide a promising, non-destructive alternative for evaluating the granular materials, offering insights into both their elastic properties and adsorption behavior.

Methods

Carbon xerogel synthesis

Carbon xerogel samples were synthesized by pyrolysis of organic precursors (Fig. 7a)71,72. The carbon xerogel precursor was prepared by polycondensation reaction from a mixture of resorcinol (1,3-dihydroxybenzene) and formaldehyde (1:2 molar ratio) diluted by deionized water. Sodium carbonate was added as a catalyst. The solution was poured into analytical glass vials (1.6 cm in diameter) and sealed airtight using screw caps. Then, the solution was exposed to 50 °C for 24 hrs and 85 °C for 24 hrs for gelation and curing. After the gelation step, the water in the pores of the wet gel was replaced by ethanol by a solvent exchange step, and the samples were dried under supercritical conditions (CO2, 45 °C, 100 bar, 24 hrs). The dry samples were then carbonized at 900 °C for 60 minutes under an argon atmosphere (heating rate was 3 K/min). In this study, granulated samples were used for material characterization, and water sorption measurements using a commercial water sorption balance, while monolithic samples from the same batch were used for ultrasound-adsorption measurements. Since both the granulated and monolithic samples originated from the same batch, their microstructure remained identical.

a Schematic illustration of carbon xerogel synthesis procedure. The precursor solution (sol) is allowed to undergo polycondensation by heat treatment to form a gel. The water medium is then replaced by ethanol and followed by supercritical drying with carbon dioxide to remove the liquid phase. The dried sample is then carbonized by pyrolysis. b Schematic of the experimental setup for the ultrasonic pulse transmission method. c A typical waveform measured for the carbon xerogel sample and the determination of the time of flight relative to the reference waveform. d Schematic of the adsorption-ultrasonic experimental setup.

Material characterization

The microstructure of the synthesized samples was imaged by SEM. The bulk (apparent) density, ρb was obtained from the volume and mass measurements of a cylindrical sample. The N2 and CO2 sorption data were obtained using a volumetric sorption analyzer (ASAP 2020 from Micromeritics Inc., USA). Before analysis, the sample was degassed under vacuum at 300 °C for at least 5 hours. Evaluation of the BET surface from the N2 sorption data was performed following the IUPAC technical report to select the correct pressure range for this microporous material31. Determination of PSD was carried out using Micromeritics Microactive software. For the PSD of the mesopores, a non-local density functional theory (NLDFT) Kernel for nitrogen on carbon with cylindrical pore geometry was used (N2-2D-NLDFT). The micropore distribution was obtained using a combination of two NLDFT models for CO2 and N2 sorption measurements (CO2 at 273 K in carbon and N2 at 77 K on carbon slit pores) using the “NLDFT advanced PSD” tool of Microactive73. The pores in xerogel have disordered structures, and neither a cylindrical nor spherical model would describe it precisely. However, use of a DFT model for carbon spherical pores74 will shift the mesopore size peak to a somewhat higher value, ~10 nm in diameter. At the same time, the other properties, such as the water bulk modulus, will be affected by a 10 nm spherical pore similarly to an 8 nm cylindrical pore75.

Before conducting ultrasound-adsorption experiments, the water sorption isotherm was obtained using a commercial sorption balance (SPS11-10μ from ProUmid GmbH Co. KG, Germany). The device uses a humidified carrier gas stream (nitrogen) to expose the sample to a defined RH at constant temperature. The humidity is measured by a calibrated capacitive humidity sensor. The amount of water adsorbed is determined from the sample mass gain. Before the measurement, the sample was crushed into granules of ~3 mm size to accelerate the sorption process. Further, we refer to this sample as “granulated sample". The measurement was performed at 25 °C in the RH range from 0% to 95% RH with steps of 5% RH for adsorption and desorption. As a condition for equilibrium of each step, the mass change of the sample had to be lower than 0.01% per 130 minutes. To determine the mass of the empty sample, the granules were pre-dried in an oven under vacuum and subsequently conditioned at 50 °C and 0% RH inside the sorption balance chamber.

Ultrasonic measurements

Xerogel samples used in this study are quite brittle and unable to withstand mechanical loads. Therefore, ultrasonic non-destructive measurements are more suitable for determining the elastic moduli of such brittle materials, offering a significant advantage over the conventional tensile testing method. Ultrasonic pulse transmission technique was used in this study to obtain both longitudinal, vL and shear, vS sound speeds through the monolithic xerogel sample76,77,78. In this method, propagation of ultrasonic waves is observed by transmitting an ultrasonic pulse from a transducer (transmitter) attached to one end of the test sample and receiving the propagated pulse by the transducer (receiver) attached to the opposite end of the sample (Fig. 7b). For porous materials, the use of conventional fluid couplants is limited as they tend to diffuse into pores of the material. Therefore, a thin nitrile rubber sheet was used as the coupling medium between the sample and transducers, following Ogbebor et al.22. The time for the ultrasonic wave propagation through the material (time of flight), Δt is obtained from the transmitted waveform captured by a digital oscilloscope. In solid materials, ultrasound propagates in the form of longitudinal and shear waves. Since the shear wave travels slower and arrives later than the longitudinal wave, both longitudinal and shear wave propagation can be captured in a single waveform (Fig. 7c). The signal amplitude (strength) of each waveform depends on the type of transducer used, as the transducers of specific types (longitudinal or shear) produce and respond best to their native type of waveform. Nevertheless, shear transducers will respond to longitudinal waves and vice versa37. By selecting the right combination of transducers, it is possible to obtain both longitudinal and shear waveforms from a single measurement. In this study, test sample was sandwiched between a longitudinal (Olympus, V1091) and a shear (Olympus, V157-RM) transducer with fundamental frequency 5 MHz and diameter 6.35 mm (Fig. 7b). Here, high frequency (5 MHz) waves with shorter wavelength (~0.5 mm) were used to achieve a better resolution in ultrasonic measurements of samples ranging from millimeter to few-centimeter in size. Ultrasonic waveforms were recorded using the longitudinal transducer as the transmitter and the shear transducer as the receiver. Then, another waveform was recorded by using the shear transducer as the transmitter and the longitudinal transducer as the receiver. In this way, the weak shear waveform can be identified accurately. Longitudinal and shear wave speeds were calculated using the measured respective times of flight (ΔtL, ΔtS), and the path length of the wave propagation through the sample (sample length). The time of flight of each longitudinal and shear waves were measured as the time gap between the highest peak position of the reference waveform (transducer-nitrile-nitrile-transducer combination) and the respective peak positions of sample waveform (transducer-nitrile-sample-nitrile-transducer combination) as shown in Fig. 7c. The longitudinal, M and shear, G moduli were derived from the respective wave speeds and material’s bulk density, ρb as,

and the bulk modulus, K is related to the above moduli as

Adsorption-ultrasonic experimental setup and procedure

Figure 7d shows the adsorption-ultrasonic experimental setup (inspired by Yurikov et al.21 and used earlier by Ogbebor et al.22) employed to obtain water sorption isotherms simultaneously with the ultrasonic measurements under humid air conditions. Water sorption by the sample was measured at discrete values of RH = p/p0, the ratio of the partial vapor pressure, p, to the saturation vapor pressure of water, p0. A series of salt solutions was used to control the RH level, ranging from 12% to 98%. In the experimental setup, the sample-transducer assembly, a sister sample, and the salt solution were placed inside a vacuum-tight container (AnaeroPack™ rectangular jar, Thermo Scientific™ R681001) held at ambient pressure. During ultrasonic measurements, it was important to maintain a constant clamping force and sample orientation between the transducers, as any variations of those could lead to errors in the measurements of signal amplitude and travel time. Nearly 1.7% decrease in travel time and ~300% increase in signal amplitude were observed due to the variation of the clamping force from relaxed position to tight position. Therefore, the sample used for ultrasonic measurements was locked in position, and the sister sample was used for the gravimetric measurements. A 40 mm box fan was used inside the container to mix the vapor-air continuously. The humidity in the container was recorded using a Vernier™ sensor with an accuracy of ±2% RH, and a resolution of 0.01% RH. The container was placed inside a thermally insulated box (a cooler box) equipped with a finned shell-and-tube heat exchanger and a large box fan. Temperature-controlled water was pumped through the heat exchanger by a Fisherbrand™ Isotemp™ bath circulator, model 6200 R20, with the temperature set to 20.00 ± 0.03 °C. Two cylindrical monolithic carbon xerogel samples of lengths 15.65 and 16.81 mm, and a diameter of 9.88 mm were used for ultrasonic and gravimetric measurements, respectively.

Repeated measurements of ultrasonic waveforms were used to monitor the water adsorption equilibration at each RH level, and the equilibration was further confirmed by comparing the mass measurements within a sufficiently long period (~24 hrs). After the RH equilibration, the target ultrasonic waveform was recorded, and the sister sample was weighed. Then the salt solution was replaced to adjust to the next RH value, and these steps were repeated to obtain the complete sorption isotherm through adsorption and desorption routes. At 93% RH, a significantly long equilibration time was observed compared to lower RH levels. Additionally, the ultrasonic data did not show a monotonic behavior as shown in Fig. 2c. Therefore, mass measurements were taken several times during the adsorption at 93% and 98% RH levels in order to monitor the equilibration. The dry mass, mdry, and the dry elastic properties of the sample were measured in vacuum (2 Torr). The dry mass and the density of the sister sample (and the sample used for ultrasonic measurements) were 0.9932(0.9448) ± 0.0002 g and 0.769(0.767) ± 0.001 g/cm3, respectively.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary Information files.

References

Murphy, W. F. Effects of partial water saturation on attenuation in Massilon sandstone and Vycor porous glass. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 71, 1458–1468 (1982).

Warner, K. L. & Beamish, J. R. Ultrasonic measurement of the surface area of porous materials. J. Appl. Phys. 63, 4372–4376 (1988).

Page, J. H., Liu, J., Abeles, B., Deckman, H. W. & Weitz, D. A. Pore-space correlations in capillary condensation in Vycor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 71, 1216 (1993).

Page, J. H. et al. Adsorption and desorption of a wetting fluid in Vycor studied by acoustic and optical techniques. Phys. Rev. E 52, 2763 (1995).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Elastic properties of liquid and solid argon in nanopores. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 25, 415302 (2013).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Influence of the Laplace pressure on the elasticity of argon in nanopores. Europhys. Lett. 105, 56001 (2014).

Schappert, K., Gemmel, L., Meisberger, D. & Pelster, R. Elasticity and phase behaviour of n-heptane and n-nonane in nanopores. Europhys. Lett. 111, 56003 (2015).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Temperature dependence of the longitudinal modulus of liquid argon in nanopores. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 5537–5544 (2018).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Liquid argon in nanopores: the impact of confinement on the pressure dependence of the adiabatic longitudinal modulus. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 27425–27432 (2018).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Distinct enhancement of the longitudinal modulus of liquid nitrogen in nanoporous Vycor glass. J. Phys. Chem. C. 126, 21745–21750 (2022).

Schappert, K. & Pelster, R. Evaluating the pressure dependence of the longitudinal modulus of an adsorbate in nanopores using ultrasound: a novel procedure taking the effect of emptying pore ends into account. J. Phys. Chem. C. 128, 21081–21089 (2024).

Pimienta, L., Fortin, J. & Guéguen, Y. Investigation of elastic weakening in limestone and sandstone samples from moisture adsorption. Geophys. J. Int. 199, 335–347 (2014).

Ilin, E., Marchevsky, M., Burkova, I., Pak, M. & Bezryadin, A. Nanometer-scale deformations of berea sandstone under moisture-content variations. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 024043 (2020).

Khajehpour Tadavani, S., Poduska, K. M., Malcolm, A. E. & Melnikov, A. A non-linear elastic approach to study the effect of ambient humidity on sandstone. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 244902 (2020).

Tiennot, M. & Fortin, J. Moisture-induced elastic weakening and wave propagation in a clay-bearing sandstone. Géotech. Lett. 1–20 (2020).

Mikhaltsevitch, V., Lebedev, M., Pervukhina, M. & Gurevich, B. Seismic dispersion and attenuation in mancos shale–laboratory measurements. Geophys. Prospect. 69, 568–585 (2021).

Ògúnsàmì, A. et al. Elastic properties of a reservoir sandstone: a broadband inter-laboratory benchmarking exercise. Geophys. Prospect. 69, 404–418 (2021).

Gao, L., Shokouhi, P. & Rivière, J. Effect of relative humidity on the nonlinear elastic response of granular media. J. Appl. Phys. 131, 055101 (2022).

Gao, L., Shokouhi, P. & Rivière, J. Effect of grain shape and relative humidity on the nonlinear elastic properties of granular media. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL103245 (2023).

Wu, R. et al. Laboratory acousto-mechanical study into moisture-induced changes of elastic properties in intact granite. Int. J. Rock. Mech. Min. Sci. 170, 105511 (2023).

Yurikov, A., Lebedev, M., Gor, G. Y. & Gurevich, B. Sorption-induced deformation and elastic weakening of bentheim sandstone. J. Geophys. Res. Solid Earth 123, 8589–8601 (2018).

Ogbebor, J. et al. Ultrasonic study of water adsorbed in nanoporous glasses. Phys. Rev. E 108, 024802 (2023).

Karunarathne, A. et al. Effects of humidity on mycelium-based leather. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 7, 6441–6450 (2024).

Gor, G. Y. Adsorption stress changes the elasticity of liquid argon confined in a nanopore. Langmuir 30, 13564–13569 (2014).

Maximov, M. A. & Gor, G. Y. Molecular simulations shed light on potential uses of ultrasound in nitrogen adsorption experiments. Langmuir 34, 15650–15657 (2018).

Dobrzanski, C. D., Gurevich, B. & Gor, G. Y. Elastic properties of confined fluids from molecular modeling to ultrasonic experiments on porous solids. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 021317 (2021).

Liu, L. et al. Water adsorption on carbon-a review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 250, 64–78 (2017).

Benzigar, M. R. et al. Recent advances in functionalized micro and mesoporous carbon materials: synthesis and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 2680–2721 (2018).

Memetova, A. et al. Nanoporous carbon materials as a sustainable alternative for the remediation of toxic impurities and environmental contaminants: a review. Sci. Total Environ. 838, 155943 (2022).

Kostoglou, N. et al. Nanoporous polymer-derived activated carbon for hydrogen adsorption and electrochemical energy storage. Chem. Eng. J. 427, 131730 (2022).

Thommes, M. et al. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 87, 1051–1069 (2015).

Iiyama, T., Nishikawa, K., Otowa, T. & Kaneko, K. An ordered water molecular assembly structure in a slit-shaped carbon nanospace. J. Phys. Chem. 99, 10075–10076 (1995).

Kaneko, K., Hanzawa, Y., Iiyama, T., Kanda, T. & Suzuki, T. Cluster-mediated water adsorption on carbon nanopores. Adsorption 5, 7–13 (1999).

Bahadur, J., Contescu, C. I., Rai, D. K., Gallego, N. C. & Melnichenko, Y. B. Clustering of water molecules in ultramicroporous carbon: In-situ small-angle neutron scattering. Carbon 111, 681–688 (2017).

Wang, H.-J., Kleinhammes, A., McNicholas, T. P., Liu, J. & Wu, Y. Water adsorption in nanoporous carbon characterized by in situ NMR: measurements of pore size and pore size distribution. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 8474–8480 (2014).

Thommes, M., Morell, J., Cychosz, K. A. & Fröba, M. Combining nitrogen, argon, and water adsorption for advanced characterization of ordered mesoporous carbons (cmks) and periodic mesoporous organosilicas (pmos). Langmuir 29, 14893–14902 (2013).

Yurikov, A., Nourifard, N., Pervukhina, M. & Lebedev, M. Laboratory ultrasonic measurements: shear transducers for compressional waves. Lead. Edge 38, 392–399 (2019).

Sears, F. M. & Bonner, B. P. Ultrasonic attenuation measurement by spectral ratios utilizing signal processing techniques. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote GE-19, 95–99 (1981).

Boehm, H. Some aspects of the surface chemistry of carbon blacks and other carbons. Carbon 32, 759–769 (1994).

Boehm, H. P. Surface oxides on carbon and their analysis: a critical assessment. Carbon 40, 145–149 (2002).

Emmett, P. H. Adsorption and pore-size measurements on charcoals and whetlerites. Chem. Rev. 43, 69–148 (1948).

Dubinin, M. et al. Adsorption of water and the micropore structures of carbon adsorbents communication 5. pore structure parameters of thermally treated carbon adsorbents and the adsorption of water vapor on these materials. Bull. Acad. Sci. USSR Div. Chem. Sci. 31, 2133–2137 (1982).

Barton, S. S. & Koresh, J. E. Adsorption interaction of water with microporous adsorbents. Part 1.—water-vapour adsorption on activated carbon cloth. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1: Phys. Chem. Condens. Phases 79, 1147–1155 (1983).

Gor, G. Y., Huber, P. & Bernstein, N. Adsorption-induced deformation of nanoporous materials – a review. Appl. Phys. Rev. 4, 011303 (2017).

Balzer, C., Braxmeier, S., Neimark, A. V. & Reichenauer, G. Deformation of microporous carbon during adsorption of nitrogen, argon, carbon dioxide, and water studied by in situ dilatometry. Langmuir 31, 12512–12519 (2015).

Amberg, C. H. & McIntosh, R. A study of adsorption hysteresis by means of length changes of a rod of porous glass. Can. J. Chem. 30, 1012 – 1032 (1952).

Balzer, C., Wildhage, T., Braxmeier, S., Reichenauer, G. & Olivier, J. P. Deformation of porous carbons upon adsorption. Langmuir 27, 2553–2560 (2011).

Ludescher, L. et al. Adsorption-induced deformation of hierarchical organised carbon materials with ordered, non-convex mesoporosity. Mol. Phys. 119, e1894362 (2021).

Chen, C. et al. Single parameter for predicting the morphology of atmospheric black carbon. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 14169–14179 (2018).

Karunarathne, A., Demidov, E. V., Hasani, A. & Khalizov, A. F. Mechanical properties of bare and coated soot aggregates probed by atomic force microscopy. J. Aerosol. Sci. 185, 106523 (2025).

Demidov, E. V., Gor, G. Y. & Khalizov, A. F. Discrete element method model of soot aggregates. Phys. Rev. E 110, 054902 (2024).

Gassmann, F. Über die Elastizität poröser medien. Viertel. Naturforsch. Ges. Zürich. 96, 1–23 (1951).

Berryman, J. G. Origin of Gassmann’s equations. Geophysics 64, 1627–1629 (1999).

Biot, M. A. Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid-saturated porous solid. I. Low-frequency range. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 168–178 (1956).

Biot, M. A. Theory of propagation of elastic waves in a fluid-saturated porous solid. ii. higher frequency range. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28, 179–191 (1956).

Gor, G. Y. & Gurevich, B. Gassmann theory applies to nanoporous media. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 146–155 (2018).

Sun, Y., Gurevich, B. & Gor, G. Y. Modeling elastic properties of Vycor glass saturated with liquid and solid adsorbates. Adsorption 25, 973–982 (2019).

Johnson, D. L. Theory of frequency dependent acoustics in patchy-saturated porous media. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 682–694 (2001).

Hill, R. Elastic properties of reinforced solids: some theoretical principles. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 11, 357–372 (1963).

Gurevich, B., Nzikou, M. M. & Gor, G. Y. Modeling patchy saturation of fluids in nanoporous media probed by ultrasound and optics. Phys. Rev. E 109, 064801 (2024).

Kuster, G. T. & Toksöz, M. N. Velocity and attenuation of seismic waves in two-phase media: part I. Theoretical formulations. Geophysics 39, 587–606 (1974).

Wagner, W. & Pruß, A. The IAPWS formulation 1995 for the thermodynamic properties of ordinary water substance for general and scientific use. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 31, 387–535 (2002).

Gor, G. Y. et al. Relation between pore size and the compressibility of a confined fluid. J. Chem. Phys. 143, 194506 (2015).

Corrente, N. J., Dobrzanski, C. D. & Gor, G. Y. Compressibility of supercritical methane in nanopores: a molecular simulation study. Energy Fuels 34, 1506–1513 (2020).

Gor, G. Y. & Bernstein, N. Adsorption-induced surface stresses of the water/quartz interface: ab initio molecular dynamics study. Langmuir 32, 5259–5266 (2016).

Gor, G. Y. Bulk modulus of not-so-bulk fluid. In Poromechanics VI, 465–472 (ASCE, 2017).

Jensen, B. D., Wise, K. E. & Odegard, G. M. Simulation of the elastic and ultimate tensile properties of diamond, graphene, carbon nanotubes, and amorphous carbon using a revised reaxff parametrization. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 9710–9721 (2015).

Berryman, J. G. Long-wavelength propagation in composite elastic media II. Ellipsoidal inclusions. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68, 1820–1831 (1980).

Berryman, J. G. Mixture theories for rock properties. In Rock Physics and Phase Relations: a Handbook of Physical Constants, ed. TJ Ahrens. Washington, DC: American Geophysical Union 205–228 (1995).

Horoshenkov, K. V. A review of acoustical methods for porous material characterisation. Int. J. Acoust. Vib. 22, 92–103 (2017).

Pekala, R. & Kong, F. A synthetic route to organic aerogels-mechanism, structures and properties. Rev. Phys. Appl. 24, 33 (1989).

Wiener, M., Reichenauer, G., Scherb, T. & Fricke, J. Accelerating the synthesis of carbon aerogel precursors. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 350, 126–130 (2004).

Jagiello, J., Ania, C., Parra, J. B. & Cook, C. Dual gas analysis of microporous carbons using 2d-nldft heterogeneous surface model and combined adsorption data of N2 and CO2. Carbon 91, 330–337 (2015).

Gor, G. Y., Thommes, M., Cychosz, K. A. & Neimark, A. V. Quenched solid density functional theory method for characterization of mesoporous carbons by nitrogen adsorption. Carbon 50, 1583–1590 (2012).

Dobrzanski, C. D., Maximov, M. A. & Gor, G. Y. Effect of pore geometry on the compressibility of a confined simple fluid. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 054503 (2018).

Asay, J. R., Lamberson, D. L. & Guenther, A. H. Ultrasonic technique for determining sound-velocity changes in high-loss materials. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 45, 566–571 (1969).

Brown, A. E. Rationale and summary of methods for determining ultrasonic properties of materials at lawrence livermore national laboratory. Technical Report. Lawrence Livermore National Lab. (LLNL), Livermore, CA (United States) (1995).

Kohlhauser, C. & Hellmich, C. Ultrasonic contact pulse transmission for elastic wave velocity and stiffness determination: Influence of specimen geometry and porosity. Eng. Struct. 47, 115–133 (2013).

Neimark, A. V., Lin, Y., Ravikovitch, P. I. & Thommes, M. Quenched solid density functional theory and pore size analysis of micro-mesoporous carbons. Carbon 47, 1617–1628 (2009).

Landers, J., Gor, G. Y. & Neimark, A. V. Density functional theory methods for characterization of porous materials. Colloids Surf. A 437, 3–32 (2013).

Acknowledgements

G.Y.G., A.F.K., and A.K. thank the support from the NSF CBET-2128679 and CBET-2344923 grants. B.G. thanks the sponsors of Curtin Reservoir Geophysics Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.K.: performing adsorption-ultrasonic experiments, conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing-original draft, visualization; S.B.: xerogel sample synthesis, performing N2, CO2, and H2O sorption measurements, analysis of PSD, writing; B.G. conceptualization, formal analysis; A.F.K. and G.R.: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, resources; G.Y.G: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, resources, project administration, funding acquisition. All authors: discussion, review and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Karunarathne, A., Braxmeier, S., Gurevich, B. et al. Ultrasound propagation in water-sorbing carbon xerogel. npj Acoust. 1, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00015-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00015-8