Abstract

Frequency-dependent elastic parameter determination for noise control materials remains challenging due to variable installation conditions. Material response depends on temperature, loading, and deformation, complicating test standardization. While multiple experimental methods exist, none are universally adopted. This study estimates the complex modulus of isotropic viscoelastic materials using stress relaxation tests. A sample between parallel plates undergoes fixed deformation while opposite-side stress is recorded. The stress-strain ratio (relaxation function) is calculated, then transformed via Laplace analysis and fractional derivative modeling to obtain frequency-dependent moduli (1 Hz–100 kHz). Results for various acoustic materials show reproducibility consistent with literature standards when compared to established techniques. The proposed method offers reliable characterization across broad frequency ranges under controlled strain conditions, addressing gaps in current testing approaches. Key advantages include simultaneous multi-frequency analysis and compatibility with typical laboratory equipment. Discrepancies with reference methods fall within expected variation ranges, validating the technique’s accuracy for engineering applications in material development and quality control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Viscoelastic and poroelastic materials are widely used in noise and vibration control applications. The micro-structural cells inherent in these materials form a complex mechanical system. To accurately evaluate their acoustic performance, it could be necessary to measure their elastic parameters, namely and for an isotropic material, the storage modulus, loss factor and Poisson’s ratio. It has been observed that these elastic parameters can vary significantly with frequency; therefore, a simple low-frequency measurement technique may not be sufficiently accurate to fully capture the viscoelastic behavior of a certain material. The experimental determination of frequency-dependent mechanical properties of viscoelastic solids can be carried out using a variety of techniques. These methods are typically categorized as either quasi-static or dynamic and generally provide measurements over a limited frequency range. The choice of the most appropriate technique depends on several factors, such as sample geometry, damping characteristics, frequency range of interest, and the presence of static preload. A comprehensive review of existing methods for determining the mechanical properties of materials used in noise and vibration control was presented by Bonfiglio et al.1 and Jaouen et al.2. In those studies, various quasi-static3,4,5 and dynamic6,7,8,9,10 techniques were discussed and compared. A common limitation of these methods is that the maximum reliable frequency is generally below 1000 Hz. Furthermore, the inter-laboratory study1 revealed a major issue: poor reproducibility among the participating laboratories. The aim of this paper is to propose a stress relaxation test method for determining the storage modulus and damping loss factor (hereafter referred to as G1 [Pa] and LossG [-], respectively) over a wide frequency range. This is achieved by measuring the time-domain relaxation function and applying a five-parameter linear viscoelastic model. The following section outlines the proposed methodology, including an innovative measurement test rig and details on the test samples. Section 3 presents a comparison of results obtained from several acoustic materials using the proposed method and alternative dynamic techniques. The influence of different static preloads and compression rates is also discussed, followed by concluding remarks.

Results

Preliminary results

Before analyzing the results of the tested materials, the procedure was validated using simulated R(t) curves generated with the fourth-order fractional derivative Zener’s model. Comparing constitutive equations, models are identical if α = β6. Model parameters are reported in Table 1.

As described in Guo et al. paper11, the function R(t) and the complex modulus can be calculated using the following expressions:

with Eα being the Mittag-Leffler function. Figure 1 depicts the comparison both for storage modulus and loss factor for simulated materials defined in Table 1.

Storage and Loss modulii for materials defined in Table 1 and generated with the fourth-order fractional derivative Zener’s model.

The agreement between the curves is very satisfactory, indicating that the model accurately captures the behavior observed in the experimental data. For both materials, the relative error is lower than 2% and 9% for storage modulus and loss factor, respectively. Table 2 summarizes values of model parameters retrieved applying proposed methodology.

Results for tested materials

As an example, Fig. 2 shows the comparison in terms of experimental and fitted relaxation functions (normalized to R(t = 0)) for all tested materials in the first 10 s of relaxation test. As mentioned in section “Results for tested materials”, the relaxation function was calculated starting from set of model parameters in the Laplace transform (Eq. (9)) and converted into the time domain using a Talbot inversion algorithm.

In Fig. 3, results in terms of the real part of the complex modulus and loss factor are shown for materials from A to D. Experiments were carried out at an ambient temperature of 24 ∘C. In addition, as discussed in the next session, the complex modulus can exhibit a dependency due to the initial static preload. To this end, tests were executed at the minimum applicable load which was around 300 Pa. The fixed strain was chosen between 5% and 7% for all test samples. From the curves in Fig. 3 it was possible to observe that, apart from material A (showing an almost negligible dependency of the complex modulus versus frequency) the remaining materials exhibited a strong variation when compared to the low frequency limit of the complex modulus.

Figure 4 shows the comparison of the complex modulus between the resonant method and the proposed technique limited to the same frequencies obtained with the latter approach. In terms of storage modulus, it was possible to observe non negligible variation mainly for material C (around 40% of relative error), while the maximum deviations for loss factor were observed to be around 0.1. Although relevant, it was concluded that deviations were within the maximum relative reproducibility standard deviation found in ref. 1 both for storage modulus and damping loss factor.

Additional tests

In this section, three different applications of the proposed methodology are presented and discussed. The first concerns the investigation of the effects of compression rate and/or static preload on the mechanical response of a given material. The second demonstrates the benefits of using a frequency-dependent complex modulus when evaluating the airborne sound transmission loss of multilayer panels in automotive applications. The third represents an attempt to determine the static Poisson’s ratio using two samples of the same material with different diameters. In this context, it should be noted that all experiments pertain to uniaxial compression conditions. Consequently, anisotropy is not accounted for in this study, despite its potential fundamental role in material behavior. In various industrial applications, fibrous materials are widely used primarily for their moldability and excellent sound-absorbing properties. In automotive applications, for example, engine encapsulations and firewalls are common uses. Due to the highly complex geometries involved, the molding process often results in significant variations in the thickness and density of the original material. To investigate how the elastic modulus varies with compression rate (and consequently with density), material E was subjected to successive compressions (from 45 mm to 10 mm). For each compression rate n, the static storage modulus G0 was calculated. The results are shown in Fig. 5. The same figure includes a fitted curve described by the empirical relation \({G}_{0}^{(n)}={G}_{0}^{(1)}{n}^{2.54}\). It is worth noting that this fitted curve is consistent with results reported in ref. 12.

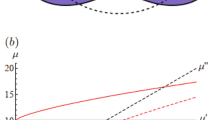

In applications where vibration dampers are used to isolate machinery from the ground, the response of the materials under varying loads is of critical importance (particularly when the machine weight may be on the order of hundreds of kilograms or more). In this study, Material D was subjected to various compression rates under different static preloads. The resulting values of the static storage modulus were measured and are shown in Fig. 6(a). These values are limited to static conditions, as such materials are typically designed to have resonance frequencies below 10 Hz. Figure 6(b) illustrates the natural frequencies of a single-degree-of-freedom vibratory system composed of a mass supported by an elastic bearing made of Material D. The analysis considers three different thicknesses of the bearing (10 mm, 25 mm, and 50 mm) placed on a rigid surface.

Regarding the application of frequency dependent mechanical properties to numerical simulation of sound transmission loss, Material B was tested when coupled to solid elastic layers. In particular, a multilayer system was made of steel plate (0.7 mm)—Material B plus a rubber mass layer (5 kg/m2–2.6 mm thick). Experimental tests were carried out according to ISO 15186-1:2003 Standard13. Rectangular panels (size equal to 1.2 × 1 m2) were mounted on a frame between two rooms. A sound source (emitting a stationary white noise) was located within a highly reverberant room with a volume of 250 m3; the averaged spatial and temporal sound pressure level Lp,s was measured using six half inches microphones. The hemi-anechoic receiving room (with a volume of 243) had highly absorbing walls, ceiling and a reflective floor. The received spatially averaged sound intensity field was measured at a distance of 15 cm from the sample surface using a BK 3547 sound intensity probe. According to ISO Standard 15186-1:2003 the sound transmission loss was calculated as TL = Lp,s − LI,r − 6[dB]. Tests were carried out in the frequency range between 100 Hz and 5000 Hz. Finally, the transfer matrix method14 was used for numerical simulations and an analytical correction was applied to consider the finite size of the panel15. Comparison between experimental test and simulations obtained using results from both resonant method and the proposed methodology is shown in Fig. 7. When the frequency dependent complex modulus was used the average of the absolute differences with respect to experimental data was lower than 2 dB, whilst differences increased up to 4 dB when the single value elastic parameters were utilized.

The final application of the method investigated in this paper is an attempt to determine the static Poisson’s ratio of a certain material. It is critically important to emphasize that variations in Poisson’s ratio resulting from static deformation are not accounted for in this study. Simultaneously, such deformation may induce significant changes in the cellular microstructure, which could substantially influence Poisson’s ratio value16.

Specifically, the procedure used follows the approach described by Langlois et al. in ref. 4. The authors proposed a method for determining mechanical properties based on the measurement of the mechanical stiffness of two disc-shaped samples with different diameters, combined with the use of polynomial relations to simultaneously calculate Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio. The compression test must be performed on two samples with different shape factors (defined as half the radius-to-thickness ratio, R/2L). For high shape factors, the Poisson effect and boundary conditions induce lateral deformations that cannot be neglected. In such cases, Young’s modulus is corrected by applying a factor that relates the apparent modulus to the true value. In the present study, the method is applied under static conditions to determine the storage modulus. Tests were carried out using two samples with diameters of 45 mm and 29 mm, respectively. The results are summarized in Fig. 8, where the intersection of the calculated curves allows for the determination of both Poisson’s ratio and the true static storage modulus, as described in ref. 4. The value of ν = 0.3 obtained for Material A is consistent with the results reported in Ref. 1.

Discussion

This paper has presented and discussed a novel method for determining the complex modulus as a function of frequency for homogeneous, isotropic, linear viscoelastic materials through a standard stress relaxation test. This approach is coupled with a curve-fitting procedure based on a fractional derivative model for linear viscoelastic solids, enabling the extraction of both storage and loss moduli across a wide frequency range. The proposed methodology was applied to a variety of open- and closed-cell materials, and the resulting data were compared with those obtained from well-established dynamic measurement techniques. The comparison showed good agreement, demonstrating the reliability and robustness of the method. Furthermore, the procedure was employed to investigate the influence of varying static preload conditions on the mechanical response, highlighting the sensitivity of viscoelastic properties to initial compression states. Significantly, the accuracy of numerical simulations for airborne sound transmission loss (particularly in multilayer systems) was improved when using frequency-dependent moduli obtained via the proposed method. This confirms the method’s value not only for material characterization but also for predictive modeling in practical engineering applications. In addition, the approach has shown potential for determining the static Poisson’s ratio, provided that two samples of the same material, differing in diameter, are tested. This represents a non-standard yet effective route for characterizing lateral strain effects in viscoelastic materials. Despite these promising results, several open questions remain. Further research is needed to fully understand the coupling between the solid and fluid phases in bi-phasic or poroelastic materials, especially under varying dynamic and static loading conditions. Moreover, the influence of the relaxation process on lateral deformation (i.e., the time-dependent behavior of Poisson’s ratio) requires deeper investigation. Extending the methodology to non-cylindrical geometries, such as cubic samples, could enable the study of anisotropy in complex materials, thereby broadening the scope of this approach for the characterization of direction-dependent properties. Overall, the method offers a versatile and practical tool for characterizing viscoelastic materials and could contribute meaningfully to improved acoustic, mechanical characterization, and numerical modeling strategies in fields such as automotive, aerospace, and materials science.

Methods

Theoretical background

Consider the function ϵ(t) as a causal application (i.e. strain in solids) acting on a material, and the function σ(t) the effect (i.e. the stress) resulting from this inducement. Boltzmann17 proposed that a variation in strain, occurring at a certain instant of time would produce a transformation during a subsequent time. According to the classical theory proposed by Volterra18, it follows that stress-strain deformation can be expressed in terms of a relaxation function:

The function R(t), also known as the memory function, is a property of the material and is a function of the time delay (t-τ) between the cause and the effect within the material. In particular, R(t) is defined for (t-τ) ≥0 and is fixed at zero elsewhere. Within this context, fractional derivative models have been used to describe the dynamic behavior of materials as they offer more flexibility in the description of their visco-elastic characteristics. In fact, starting from the relevant model constitutive equation and replacing the integer order time derivatives of stress and strain with fractional order derivatives, then the general form of the ‘constitutive equation’ for the conventional viscoelastic model can be expressed as:

where 0 < α1 < α2 < ⋯ < αm < 1 and 0 < β1 < β2 < ⋯ < βn < 1 are material constants.

Starting from Eq. (3), Pritz suggested a five-parameter model assuming that all parameters are zero except for a0, a1, a2, b1, α1, α2, and β119. Moreover, in analogy with the fractional Zener’s model, the author assumes α1 = β1 = β and α2 = α, with α > β. With such assumptions and setting b1 = τβ, a0 = G0, a1 = G1τβ, and a2 = (G∞ − G0)τα, it follows that Eq. (3) can be written as:

In the previous equation, G0 is the static modulus of elasticity, G∞ is related to the high-frequency limit value of the dynamic modulus and τ is the relaxation time. The complex modulus of the model is derived by transforming Eq. (4) into the frequency domain using a Fourier transform operator. The derivation results in the following expression for the complex modulus in the frequency domain:

From a practical point of view, it is possible to solve viscoelasticity problems as elasticity problems combined with a complex modulus that is frequency dependent. This property is known as the elastic/viscoelastic equivalence principle20. The time domain relaxation function R(t) and the frequency domain complex modulus G*(jω) can be linked using a Laplace Transform. In which case, Eq. (2) can be written as follows:

If a direct variable transform (G(jω) to s) is introduced into Eq. (6), then the Laplace transform of the relaxation function can be written as:

where m=G0, a = τβ, b = G0τβ and c = (G∞ − G0)τα.

Proposed methodology

The problem of interconversion between linear viscoelastic material functions in time, Laplace-transform and frequency domains has been fully investigated in published literature21,22,23,24 and most of the approaches recall the fitting of a “Prony” series. This paper presents an approach that makes use of the five-parameter model and related constitutive relation in Eq. (4). The starting point of the proposed methodology, hereinafter referred to as ‘MechRelax’, requires the determination of the relaxation function R(t) using a well-established relaxation test assuming small deformations of lower than 10%. Stress relaxation is a time-dependent decrease of the stress under a constant strain that is studied by applying a fixed amount of deformation to a specimen and measuring the load required to maintain it as a function of time. At the beginning of the experiment, the strain is applied to the specimen at a given rate to reach the desired compression and maintained constant for a predefined time. The stress decay, which occurs because of stress relaxation, is observed as a function of time.

Considering standard relaxation experiments the imposed strain can be written as ϵ(t) = ϵ0H(t), where H(t) is the Heaviside function and ϵ0 the constant strain. Once the relaxation test has been carried out a fitting procedure for the inverse estimation of model parameters (i.e. G0, G∞, τ, α and β) is implemented. The minimization procedure is based on a bounded nonlinear best-fit scheme25. In particular:

-

for each set of model parameters, starting from experimental values of stress and strain, fractional derivatives in Eq. (4) are calculated using following expression:

$$\frac{{d}^{n}f}{d{t}^{n}}=\frac{1}{\Gamma (n)}\mathop{\int}\nolimits_{0}^{t}{(1-\tau )}^{n-1}f(\tau )\,d\tau$$(8) -

the procedure continuously runs until the following cost function is minimized:

$$\begin{array}{r}CF=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{t=0}^{N}\left\vert \sigma (t)+{\tau }^{\beta }\frac{{d}^{\beta }}{d{t}^{\beta }}\sigma (t)-\right.\\ {G}_{0}\epsilon (t)-{G}_{0}{\tau }^{\beta }\frac{{d}^{\beta }}{d{t}^{\beta }}\epsilon (t)-\\ \left.({G}_{\infty }-{G}_{0}){\tau }^{\alpha }\frac{{d}^{\alpha }}{d{t}^{\alpha }}\epsilon (t)\right\vert \end{array}$$(9) -

once the model parameters have been determined, the frequency dependent complex modulus can be calculated for any frequency of interest using Eq. (5).

An initial estimate for the static modulus G0 is obtained by preliminarily fitting the long-time portion of the relaxation function (after 3 minutes, ensuring a correlation coefficient r2 ≥ 0.99) using a homographic function of the form (x1t + x2)/(x3t + x4). Notably, the ratio x1/x3 represents the horizontal asymptote of the curve. An initial estimate of the relaxation time τ is derived from theoretical considerations presented in ref. 26. Specifically, when the relaxation function is expressed in terms of a generalized Mittag-Leffler function, it can be shown that the intersection point of the asymptotes (representing the short- and long-time behaviors) corresponds to the characteristic relaxation time. As an additional check of the proposed procedure using the same set of parameters the Laplace transform in Eq. (9) is converted into the time domain relaxation function using a Talbot inversion algorithm27 and compared with experimental data. In this research the duration of the tests was fixed at 10 minutes and the complex modulus calculated in the frequency range between 1 Hz and 100 kHz. The main hypotheses of the proposed methodology were:

-

Materials were considered as homogeneous and isotropic linear viscoelastic solids (i.e. a low coupling between the material fluid and solid phases for poroelastic materials was assumed in this regime).

-

The Poisson’s ratio effect was neglected as well as its time and frequency dependency.

-

The nonlinear nature of the material under large deformations and its hyperelastic behavior are not taken into account28,29.

A similar approach was proposed by Guo et al.11. The authors used a four-parameter fractional derivative Zener’s model converted into the time domain relaxation function by the application of a Mittag-Leffler function30 which is strictly defined for the selected frequency domain model. The advantage of the proposed methodology is that it does not require any explicit definition of the Mittag-Leffler function but can be extended to any viscoelastic model once the frequency domain modulus is defined as well as its constitutive equation.

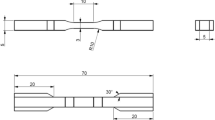

Measurement set-up and tested materials

A novel test-rig was developed for the execution of the relaxation test. The test material sample, being cylindrical with a diameter of 45 mm or lower, mounted between a bottom fixed plate and an upper moving plate. The force was measured using a load cell (S2Tech 535QD with a measurement range of 0–25 kg FS). The applied deformation was measured using a S2Tech LVDT displacement transducer (measurement range 10 mm). The static preload was adjusted using a threaded rod while the imposed deformation was adjusted using a micro-metric screw. Finally, the deformation was applied using a pneumatic cylinder (Metal Work double acting piston 40 mm diameter, stroke 10 mm) working at an operating pressure of approximately 1 bar. A scheme of the lay-out and the test rig are depicted in Figs. 9 and 10. Force and displacement data were acquired using a National Instruments acquisition device (NI USB 4431) with a sample frequency of 12500 Hz. The post-processing procedure was developed on the Labview software platform.

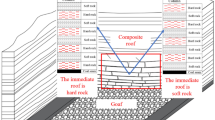

Experiments were undertaken on five materials (labeled from A to E) whose descriptions are summarized in Table 3. Material A was one of the most homogeneous and isotropic acoustic materials and exhibited a relatively low dependency of its elastic properties on temperature and frequency10. Material B was selected because it showed a strong viscoelastic behavior1. Material C was a consolidated granular material of relatively high density and strong viscoelastic behavior. Material D was a high-density closed-cell foam highly utilized as a vibration damper and thus able to resist very high static loads over time. Finally, material E (medium-density fibrous material), due to its negligible frequency dependence of elastic properties, will be used to investigate the variation of the static storage modulus as a function of compression rate. This choice of materials covered a broad range of densities typical to those found in media used for noise control and vibration insulation.

Each material was also tested by using a well-established dynamic method based on the resonance frequency and half-power estimation of a single degree of freedom transmissibility function in the frequency domain19. The top surface of the specimen was loaded with a mass. The bottom surface of the specimen was attached to a rigid plate which was excited with a shaker. This technique was based on the measurement of the amplitude of the transmissibility function that being the ratio between top and bottom plate accelerations determined over a broad frequency range. The resonance frequency and quality factor were determined from this frequency dependent transmissibility function and related to the storage modulus and loss factor of the material specimen.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bonfiglio, P. et al. How reproducible are methods to measure the dynamic viscoelastic properties of poroelastic media? J. Sound Vib. 428, 26–43 (2018).

Jaouen, L., Renault, A. & Deverge, M. Elastic and damping characterizations of acoustical porous materials: available experimental methods and applications to a melamine foam. Appl. Acoust. 69, 1129–1140 (2008).

Sahraoui, S., Mariez, E. & Etchessahar, M. Mechanical testing of polymeric foams at low frequency. Polym. Test. 20, 93–96 (2000).

Langlois, C., Panneton, R. & Atalla, N. Polynomial relations for quasi-static mechanical characterization of isotropic poroelastic materials. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110, 3032–3040 (2001).

Geslain, A., Dazel, O., Groby, J.-P., Sahraoui, S. & Lauriks, W. Influence of static compression on mechanical parameters of acoustic foams. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 130, 818–825 (2011).

Pritz, T. Dynamic Young’s modulus and loss factor of plastic foams for impact sound isolation. J. Sound Vib. 178, 315–322 (1994).

Etchessahar, M., Sahraoui, S., Benyahia, L. & Tassin, J. F. Frequency dependence of elastic properties of acoustic foams. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117, 1114–1121 (2005).

Roozen, N., Labelle, L., Leclère, Q., Ege, K. & Alvarado, S. Non-contact experimental assessment of apparent dynamic stiffness of constrained-layer damping sandwich plates in a broad frequency range using a nd: YAG pump laser and a laser doppler vibrometer. J. Sound Vib. 395, 90–101 (2017).

Geslain, A. et al. Spatial Laplace transform for complex wavenumber recovery and its application to the analysis of attenuation in acoustic systems. J. Appl. Phys. 120, 135107 (2016).

Bonfiglio, P., Pompoli, F., Horoshenkov, K. V. & Rahim, M. I. B. S. A. A simplified transfer matrix approach for the determination of the complex modulus of viscoelastic materials. Polym. Test. 53, 180–187 (2016).

Guo, X., Yan, G., Benyahia, L. & Sahraoui, S. Fitting stress relaxation experiments with fractional Zener model to predict high frequency moduli of polymeric acoustic foams. Mech. Time Depend. Mater. 20, 523–533 (2016).

Campolina, B., Dauchez, N., Atalla, N. & Doutres, O. Effect of porous material compression on the sound transmission of a covered single leaf panel. Appl. Acoust. 73, 791–797 (2012).

ISO 15186-1:2003. Acoustic—measurement of sound insulation in buildings and of building elements using sound intensity. (International Organization for Standardization, 2003).

Allard, J. F. & Atalla, N.Propagation of Sound in Porous Media: Modelling Sound Absorbing Materials https://books.google.it/books?id=TlgO96VLYPYC (Wiley, 2009).

Bonfiglio, P., Pompoli, F. & Lionti, R. A reduced-order integral formulation to account for the finite size effect of isotropic square panels using the transfer matrix method. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 139, 1773–1783 (2016).

Mao, H., Rumpler, R. & Göransson, P. An inverse method for characterisation of the static elastic Hooke’s tensors of solid frame of anisotropic open-cell materials. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 147, 103198 (2020).

Boltzmann, L.Zur Theorie der Elastische Nachwirkung (On the Theory of Elastic Effects). 241 (Annalen der Physik, 1878).

Volterra, E. & Zachmanoglou, E.Dynamics of Vibrations. No. v. 2 in Dynamics of Vibrations https://books.google.it/books?id=ukK80AEACAAJ (C.E. Merrill Books, 1965).

Pritz, T. Five-parameter fractional derivative model for polymeric damping materials. J. Sound Vib. 265, 935–952 (2003).

Salençon, J.Viscoélasticité (Viscoelasticity) (Presse des Ponts et Chaussés, 1983).

Schwarzl, F. & Struik, L. Analysis of relaxation measurements. Adv. Mol. Relax. Process. 1, 201–255 (1968).

Ferry, J.Viscoelastic Properties of Polymers https://books.google.it/books?id=9dqQY3Ujsx4C (Wiley, 1980).

Tschoegl, N. W.The Phenomenological Theory of Linear Viscoelastic Behavior (Berlin, Heidelberg\: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 1989).

Park, S. & Schapery, R. Methods of interconversion between linear viscoelastic material functions. part i—a numerical method based on prony series. Int. J. Solids Struct. 36, 1653–1675 (1999).

Lagarias, J. C., Reeds, J. A., Wright, M. H. & Wright, P. E. Convergence properties of the nelder–mead simplex method in low dimensions. SIAM J. Optim. 9, 112–147 (1998).

Friedrich, C. & Braun, H. Generalized Cole-Cole behavior and its rheological relevance. Rheologica Acta 31, 309–322 (1992).

TALBOT, A. The accurate numerical inversion of laplace transforms. IMA J. Appl. Math. 23, 97–120 (1979).

William, O. R. 2large deformation isotropic elasticity - on the correlation of theory and experiment for incompressible rubberlike solids. Proc. R. Soc. Lond https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0020722519322724 (1972).

Wilkinson, A., Crété, J.-P., Job, S., Rachik, M. & Dauchez, N. Contact mechanics of open-cell foams with macroscopic asperities. Int. J. Solids Struct. 294, 112769 (2024).

Trujillo, J. J., Kilbas A. A., Srivastava H. M. Theory and applications of fractional differential equations http://lib.ugent.be/catalog/ebk01:1000000000357977 (Elsevier, 2006).

Acknowledgements

The datasets used and analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author conceived the idea, developed the methodology, performed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bonfiglio, P. A mechanical relaxation test for the determination of the frequency dependent complex modulus of linear viscoelastic materials. npj Acoust. 1, 21 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00029-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00029-2