Abstract

In the Arctic, amplified climate change enables increased human activity, adding to sounds in the ocean. Future guidelines need to know local baselines and how best to measure anthropogenic impacts. The EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive uses “shipping bands”, third-octave bands centred on 63 Hz and 125 Hz. Addressing the lack of measurements, acoustic models often use satellite recordings of ship tracks, We investigate sound levels in Cambridge Bay (Nunavut, Canada) between 2015 and 2024, comparing May (full ice cover, no shipping) and August (little to no ice, shipping activity). We show “shipping bands” should include frequencies up to several kHz and sounds include snowmobiles, aircraft and small vessels untracked by satellites. This will need addressing in future guidelines. This is particularly important because of the development of Arctic shipping routes, increasing resource exploration and tourism, amplified by current plans for the expansion of mining, drilling and other geostrategic pressures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change happens three times faster in the Arctic1, with declining sea ice and changing ecosystems2, against a background of ocean temperatures increasing3 in the upper 2000 m. This affects its natural soundscapes4, as easier and increasing access to the Arctic waters introduces additional sounds which can be heard hundreds of kilometres away5. It is therefore important to design relevant guidance on the introduction of anthropogenic sounds, and the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD6) is often cited as a model. It has been the first legislation globally to address underwater noise pollution explicitly7. Its Descriptor D11C2 for “continuous low-frequency sound” emphasizes the use of third-octave bands centred on nominal frequencies of 63 Hz and 125 Hz6,8, generally associated with shipping and more generally with anthropogenic noise. Later studies (summarised in7) reported that ship noise may peak at higher frequencies (up to several kHz) and the 2014 TG Noise monitoring guidance recommended that frequencies of up to 20 kHz be considered in the monitoring of this indicator6. Originally developed for open waters around Europe, the MSFD also applies to its Arctic regions. Its “shipping bands” have been used to model human impacts in the Arctic, but ambient sounds decrease in the presence of ice5 whereas sound propagation varies with ice thickness and roughness9,10. For these reasons, it is appropriate to investigate how the MSFD recommendations could be adapted to the dynamic and variable Arctic environments.

Shipping is the largest source of anthropogenic sounds. It has steadily and significantly increased global contributions to underwater sounds worldwide11,12 and models13 suggest that at the current rate, the global shipping noise emissions would double every 11.5 years. As sea ice decreases and sailing seasons expand, shipping is due to expand along the Northwest Passage, the Northern Sea Route and ultimately the Transpolar Sea Route directly across the North Pole14,15. Analyses of shipping in Arctic Canada for the 26-year period of 1990 to 201516 already show the distances travelled by ships nearly tripled. The most common ships were general cargo vessels, government icebreakers and research ships, whereas pleasure crafts (yachts) were the fastest growing vessel type. Arctic expedition cruise vessels are also an emerging source of underwater sounds, including icebreaking activities, speedboat deployments17 and mooring in ecologically sensitive areas (Ekaluktutiak Hunters & Trappers Organization, pers. comm., 2023). Fishing vessels are less visible, partly because fishing is limited by the International Agreement to Prevent Unregulated Fishing in the High Seas of the Central Arctic Ocean (which entered into force in 2021, for 16 years), partly because community-based fishing uses smaller vessels, closer to shore18. Spatial shifts in shipping during 1990–2015 have also favoured active mining areas and the more sheltered southern route of the Northwest Passage16. Driven by economic developments and geostrategic imperatives, offshore construction (harbours, resource extraction facilities, cable and pipeline laying) is also expected to increase over the coming years. Mining is expected to develop across the Arctic, in particular in Nunavut (Canada), Russia and Greenland19 and this will often include marine shipping of the resources extracted. Underwater sounds from near-shore activities and shipping lanes are known to affect local wildlife and subsistence hunting/fishing20,21 and they are considered important challenges22. In some countries, regulators are investigating how best to manage expected increases in sound levels underwater23, but there is still some debate on the methodology, in particular the choice of frequency bands.

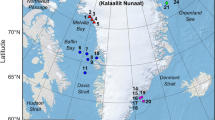

Here, we use long-term continuous acoustic measurements24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 from the Community Observatory installed in 2012 by Ocean Networks Canada (ONC) in Cambridge Bay (Nunavut). Cambridge Bay (69°06’51.24”N; 105°03’32.28”W), also known in Inuinnaqtun as Ekaluktutiak (“good fishing place”), hosts a community of less than 2,000 people. It is the largest stop for passenger and research vessels along the southern route of the Northwest Passage (Fig. 1). Independent, recent measurements in the outer Dease Strait32 recorded very few ships, with their higher source levels belonging to large ships like tankers and bulk carriers, and the lower levels associated with smaller vessels like tugs and research ships. Cambridge Bay Airport is located approximately 2 km southwest from the ONC hydrophone. In season, it operates scheduled flights (including large planes like Boeing-737) as well as charter and cargo. The Cambridge Bay Water Aerodrome is located east, less than 2 km away from the ONC site. Because of the presence of ice, it is generally operated only from mid-July until mid-September, although ice may be encountered well into August.

This map shows individual ship traffic information, provided by the Arctic Ship Traffic Database (ASTD) of the Arctic Council’s working group on Protection of the Marine Environment (PAME), using Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). AIS positions are recorded every six minutes and the present map shows August traffic, cumulated from 2015 to 2024, The main shipping lane passes in front of Cambridge Bay and there is regular traffic going into the bay itself.

Cambridge Bay is therefore a good case study to assess how human activities affect the local underwater soundscape, and we aim to address the following research questions:

-

1.

How do the MSFD “shipping bands” fare in polar environments? What are the differences between seasons?

-

2.

Which human activities (other than shipping) could contribute to the underwater soundscape?

-

3.

Beyond the MSFD shipping bands, should other frequency bands be used to assess human impacts and up to which frequency?

-

4.

Are satellite records of shipping (using the Automatic Identification System) enough to assess and/or model human contributions to soundscapes?

Results

This section presents answers to these four research questions, based on ten years of acoustic measurements. See the Methods section for details of the processing.

MSFD “Shipping Bands” in Different Arctic Seasons

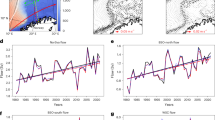

The Arctic seasons are very contrasted, with little to no ice in summer and full ice cover in winter. Figure 2 shows the mean local ice cover in each month, from January 2015 to December 2024, and the summer seasons are easily identifiable. They vary slightly from year to year, at least if defined only by the local ice cover (regional ice cover from satellite ice charts was also assessed). These summer seasons also correspond to the highest numbers of AIS entries for the region of Cambridge Bay, identified with sharp and narrow peaks, except in late 2015. AIS positions are logged every 6 min, meaning that 1800 entries in a month correspond to at least 180 h of shipping activities (or longer if ships transmit sound when entering or leaving the area but their last/next AIS position is outside the zone). The total number of ship entries in each period can also be affected by the same ship re-entering the area several times. It is therefore better to consider the number of days where shipping has been recorded. This leads us to compare the months of May (full ice cover, no shipping) and August (little to no ice cover, highest shipping). This contrast in seasons aligns with the community observations of marine transportation compiled in18.

Figure 3 compares variations in the “shipping bands”, third-octave levels centred on 63 Hz and 125 Hz, with the broadband (10 Hz – 32 kHz) Sound Pressure Levels for the months of May and August (for years when enough data is available in both months). Broadband levels are generally louder in average by approximately 10 dB in August (with a standard deviation of 5.7 dB) than in May (with a standard deviation of 2.8 dB). Louder outliers are 10 times more present than quieter ones (respectively 1.95% and 0.18% of all events). The mean levels are generally louder as the month progresses and navigation becomes easier. With only 5 AIS entries (Fig. 2), August 2020 is an exception, because of the COVID lockdown, and its broadband levels are generally similar to those of May. The Sound Pressure Levels for the months of May between 2015 and 2024 are generally similar and smaller, with much less variation from year to year or from week to week.

Boxplots showing the variation of Sound Pressure Levels, broadband (10 Hz–32 kHz, top) and for the third-octave bands of 63 Hz (middle) and 125 Hz (bottom), for the months of August (left) and May (right). Months with not enough acoustic data are not represented. The red lines go through the mean values of each plot. For statistical reasons, only the first four weeks of each month are represented.

The individual “shipping bands” follow each other and the broadband Source Pressure Levels (SPLs) in August, and a Pearson’s correlation test shows r values of 0.87 (63-Hz band) and 0.90 (125-Hz band), with 95% confidence intervals CI of [0.85, 0.89] and [0.89, 0.91], and p values of 1.1 × 10-8 and 2.3 × 10-10 respectively. These very strong correlations show the main contributions to broadband impacts are indeed mostly coming from the “shipping bands”. But week-to-week variations do not follow the distribution of AIS-recorded traffic (Fig. 4). Levels lower than expected can be attributed to propagation losses if the ships are further away, whereas higher levels mean that non-AIS ships or other sources of sound are adding to these sound levels.

No AIS shipping has been recorded in some weeks and this can be contrasted with the sound levels in Fig. 3.

Conversely, for the months of May, the 63-Hz band is less well correlated with the broadband values (r = 0.68, 95% CI [0.64, 0.72] and p = 1.5 × 10-5) whereas the 125-Hz has correlation values similar to the months of August (r = 0.88, 95% CI [0.86, 0.90] and p = 1.9 × 10-11). The years 2020, 2023 and 2024 also show a near-absence of the quieter outliers. The correlation with broadband levels is still relatively strong but it cannot be explained by the presence of shipping, non-existent at this time of year (Fig. 2).

Other Human Contributions to Soundscapes

The ice cover in May isolates the hydrophone from weather events, and ice processes are associated with different sounds33, shorter or at different frequencies. Thermal cracking is generally broadband and melting is associated with higher frequencies, as also measured by34. This section highlights some of the longer and louder sounds identified in the data selected for this study (months of May and August).

Sounds associated to human activities include small and large ships in summer: some of them are audible for a long time as they enter Cambridge Bay and reach the harbour, whereas smaller ships are audible for shorter periods. Their frequency signatures are concentrated below 125 Hz but can extend higher for short periods (Fig. 5).

Activities from the Cambridge Bay Airport and the Cambridge Bay Water Aerodrome are evidenced by the regular hearing of aircraft (Fig. 6). The fact that aircraft sounds above water can be measured underwater has been documented by a series of thorough studies35. The sound from a light aircraft in flight is generated primarily by the propeller, which produces a sequence of harmonics in the frequency band between about 80 Hz and 1 kHz. Aural examination of the present measurements confirms that most of the sound comes from the propeller(s), spanning 40 Hz to 8 kHz (Fig. 6). The number of aircraft audible at the ONC site varies, presumably based on approach paths and aircraft types.

In icy seasons, if the ice cover is thick and stable enough, this allows a range of anthropogenic activities, including transportation using snowmobiles and All-Terrain Vehicles18. Cambridge Bay is also famed for its Omingmak Frolics, a week-long spring festival featuring snowmobile races (and usually held in May). Figure 7 shows a typical snowmobile spectrogram. Loud tonals (below a few hundred Hz) are associated with higher frequencies as the vehicle passes above the hydrophone. These results are in line with other studies of snowmobile sounds (36; Cook, pers. comm., 2023).

Identification of loud, continuous sounds of human origin is not always straightforward, as some acoustic signatures can be very similar (e.g. machinery above the ice or in neighbouring open water) and some sound sources can happen in conjunction (e.g. several snowmobiles or several ships). Aural identification of all sound sources has been compared for the months of May 2018 and August 2018 (Fig. 8, from33). In May, no ships were identified (which is logical). There were 77 instances of various unequivocally anthropogenic sounds (e.g. machinery) and 1,966 recordings of snowmobiles. In August, 147 individual recordings were interpreted as ship sounds, 1 as unambiguously airborne (from the propeller sound), 39 as generic anthropogenic sounds and 13 as “unattributed”. The single detection of a snowmobile is explained by the presence of a persistent ice patch in Cambridge Bay, identified from satellite ice charts of the same period. In May, anthropogenic sounds can be as loud as 90 dB up to 1 kHz and snowmobiles can be as loud as 80 dB between 40 Hz and 1 kHz. Conversely, in August, the different sounds are more varied. Sounds from ships show higher mean SPLs at frequencies lower than 63 Hz and higher than 125 Hz and anthropogenic sounds extend up to 700 Hz. Aural identification of sound sources in other years (Table 1) could be used but it is limited by the accuracy of qualitative identification of all sound sources in an extremely large dataset. The main conclusion is that there are many anthropogenic sources of sound, from the expected (ships, snowmobiles) to the less expected (aircraft, machinery, idling vessels), and that they all contribute significantly to the MSFD “shipping bands” as well as other bands.

Sound identification. Aural identification of the different sounds in May and August 2018, showing the mean sound levels (lines), percentiles (points for each third-octave band) and the numbers of individual events identified (for example 1966 snowmobile recordings in May). From33.

Frequency Content of Loud, Continuous Sounds

To match MSFD Descriptor D11C2 for “continuous, low-frequency sounds”, we restrict the analyses to measurements where the weekly mean SPL is exceeded by at least 10 dB for at least 1 min (see Methods). For each month of May and August between 2015 and 2024, we calculate the average SPL of all loud events, in third-octave bands (blue bins, Fig. 9). This can be related to the mean SPL (for both loud and quiet periods) of the entire month (black line, Fig. 9). We also looked at the difference between the months of August and May for each year (bottom plots, Fig. 9).

Frequency contributions of loud, continuous events for August (top) and May (middle). The blue bins show the mean SPL for each third-octave band. The MSFD bands of 63 Hz and 125 Hz are highlighted in red. For reference, the mean SPL for all measurements across the entire month is indicated with a black line. For each month, the numbers in the top right of each subplot correspond to the mean, corrected ice draft above the hydrophone (in metres), the number of loud, continuous events identified (in red) and the number of measurements available for the month. For example, for August 2015, the mean ice draft was 0.0 m and there were 108 loud, continuous events identified in measurements covering 60.7% of the entire month (for May 2015, the mean ice draft was 1.7 m and 128 loud, continuous events were identified in measurements covering 92.0% of the entire month). Bottom: difference between the frequency contributions of August and May.

For the months of August, when shipping is present, the sound levels of the louder events are systematically lower (by up to 5 dB) in the 63-Hz band than the 125-Hz band. The same is true for the mean sound levels (black lines in Fig. 9), for most summers (a few dB, up to ca. 10 dB in 2015). For the months of May, when there is no shipping, both bands show relatively similar levels. Interestingly, the 63-Hz band is somewhat louder (a few dB) than the 125-Hz band for the average sound levels (for all measurements during the month), but generally a bit less loud (a few dB) when considering only the louder events. The study of shipping levels in Falmouth Bay (UK) showed that the 125-Hz levels were higher (3.4 dB) than the 63-Hz ones37. This was attributed to the increased presence of smaller, recreational vessels, and the effects of acoustic propagation in water depths similar to those of Cambridge Bay ( < 40 metres and < 20 metres, respectively).

In the months of August, the number of loud events increases regularly from year to year, with 2024 going back to the 2019 (pre-pandemic) level. The frequency distributions of these louder events are significantly higher than the mean SPL (up to 40 dB in some cases), extending well into the kHz range. Interestingly, the sound levels of loud, continuous events are lower in 2018 (which is understandable, as only 1 ship was tracked by AIS) and 2019 (which is more difficult to interpret, as this month had the highest number of individual ships tracked by AIS) (Figs. 2 and 4). These sound levels are similar to those of August 2020 (during the COVID lockdowns) and they increase again in 2024.

Conversely, in the months of May, the MSFD bands are amongst the loudest (although there are no ships). The frequency distributions of loud events tail off steeply above 1 kHz, and the number of loud events is relatively similar in most years (apart from May 2020, at the peak of the COVID lockdown). By using the arbitrary threshold of 1 min, these loud events might not include all snowmobile events (Table 1), but they nonetheless represent the most significant additions to underwater soundscapes.

The differences between sound levels in August and May (Fig. 9, bottom row) clearly show that the mean SPLs (black lines) are always higher in August than in May. However, the differences in frequency contributions are very variable. In August 2015 and August 2016, all third-octave bands contribute higher sound levels (close to 20 dB for some bands) than in May. In August 2018, 2019, and 2020, however the frequency contributions are lower than in May, except above 1 kHz. In August 2024, the contributions from frequencies below 1 kHz are again louder, and so are the contributions above 1 kHz, up to the maximum frequency of 32 kHz.

In conclusion, the comparison of sound levels for the months of May and August between 2015 and 2024 shows that the MSFD shipping bands are not the loudest or most representative. In summer, levels in the 63-Hz band are generally much lower than in the 125-Hz band, both in general (all sounds) and for the louder sounds only. In winter, the 63-Hz and 125-Hz bands are at generally similar levels. Other frequency bands should therefore be considered. This is in line with the observations of7, who mention the use of the 2-kHz third-octave band by38 and highlight a study39 showing that the higher-frequency components of boat noise may be poorly correlated with the MSFD bands. Similarly, another study40 showed the sounds of small personal watercraft in Australia contributed to frequencies in the range of 100 Hz to 10 kHz, with an additional peak at 15 Hz. Anthropogenic impacts measured in Croatia41 showed third-octave levels were louder (up to ~ 4 dB) between 350 Hz and 2 kHz in summer, but smaller (negligible to 1.5 dB) between 60 Hz and 250 Hz. Other studies42 also found that the noisiest band level was centred on 200 Hz, therefore showing that sound levels need monitoring across a wider range of frequencies. And a systematic survey of small vessels on controlled paths43 showed their acoustic signatures extending well into the kHz range too. In the present case, another observation is the seasonal difference: the frequencies most representative of loud events extend well above 1 kHz in open-water season whereas they do not extend beyond 1 kHz at the maximum extent of ice cover. The extension to higher frequency bands should depend on the ice cover (and therefore also the type of human influences, from snowmobiles and ATVs in winter to large and small ships in summer).

AIS ship tracking and soundscape contributions

Satellite tracking of ships is enabled by the Automatic Identification System (AIS). AIS transponders are only compulsory on ships of 300+ gross tonnage engaged on international voyages, cargo ships of 500+ gross tonnage not engaged on international voyages and all passenger ships irrespective of size. AIS measurements have been very useful to assess the importance of shipping-related sounds in areas like the North Sea44,45 and to model potential impacts of ships with known source levels in the NE Atlantic46 and across the Arctic47.

In the environment of Cambridge Bay, AIS records show the main shipping lane is at the far end of the bay (Fig. 1). The largest number of AIS entries (Fig. 4) occurs in 2019 (7 unique vessels) and 2024 (4 unique vessels). The largest numbers of ships identified aurally (Table 1) however occur in 2015 (260 measurements) and 2020 (212 measurements). In general, the numbers of ships heard is much larger than the numbers of ships tracked by AIS. These spectrograms also show many ship sounds extend into the kHz range (e.g. Figure 5). AIS-based measurements are therefore greatly underestimating the amount of overall traffic. This is in line with the in-depth study48 of 5 years of shipping around Scotland, showing 67% of the traffic was made of non-AIS vessels.

Soundscape contributions are often modelled based on AIS records46,47,49. The benchmarking of different models and the comparison with available measurements show general agreement in deeper waters (e.g. in the NE Atlantic46). In coastal waters, more accessible to non-AIS traffic, soundscape contributions can differ by up to 10 dB because of these smaller vessels and other anthropogenic sources. At Arctic latitudes, AIS is more susceptible to satellite coverage limitations, along with potential failures in vessel infrastructure and data flow (present at all latitudes). As pointed out most recently48, capturing non-AIS contributions is very important for the management of activities and impacts in coastal environments, and the present article shows the importance of small vessels and other contributors like snowmobiles, aircraft and machinery in the Cambridge Bay environment.

Discussion

In summer, the louder sounds are strongly correlated with their expression in the MSFD bands, but week-to-week variations do not follow the distribution of AIS-recorded traffic (Fig. 4). For example, lower sound levels are observed in August 2018 (with only 1 ship tracked by AIS) and 2019 (with the highest number of individual ships tracked by AIS) (Figs. 2 and 4). Non-AIS ships or other sources of sound are adding to these sound levels. In winter, the 63-Hz band is less correlated with the broadband values and the 125-Hz band has correlations similar to summer, although there is no shipping (Fig. 2). The last winters (2020–2024) also show a near absence of the quieter outliers in both bands. The MSFD bands are therefore including many loud, non-shipping sources. These sounds could come from geophony (mainly weather, here), cryophony (ice dynamics), biophony (vocalising animals) and anthropophony (sounds of human origins but not necessarily associated with shipping).

In line with5, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient r for hourly wind speeds and corresponding mean sound levels (720 to 744 points for 30- and 31-day months respectively), along with their 95% confidence intervals (CI).The louder ambient sound levels are more significantly correlated with wind speeds (r > 0.5, 95% CI [0.44, 0.55]) in August 2018 (for frequencies > 200 Hz), August 2019 ( > 1.2 kHz), August 2020 ( > 500 Hz) and May 2020 ( > 5 kHz), all frequencies above the MSFD bands. Conversely, they are anti-correlated with external temperatures (r < –0.5, 95% CI [-0.55, -0.44]) for all years except 2023–2024 and not correlated with first-derivative changes in temperature (which would influence ice dynamics). Specifically, both MSFD bands are poorly correlated with wind speeds (r < 0.35, 95%, CI [0.28, 0.41]) in summer and not correlated with wind speeds (r < 0.3, CI [0.23, 0.36]) and temperatures (r < 0.5 and generally close to zero) in winter. Using the Ainslie model50 benchmarked in49, we checked that the contribution of wind to the soundscapes was always well below the levels of Fig. 9. This verifies that sounds audible in the MSFD bands are not related to external weather and sea state.

There is extensive literature on sounds from ice dynamics, summarised inter alia in33. Collisions between ice blocks last a few seconds at most, with energies concentrated at frequencies < 1 kHz; fracturing is associated with broadband, transient sounds, at frequencies < 3 kHz and thermal cracking is a broadband transient sound with low-frequency peaks. Processes likely to last one minute or longer are shearing (mostly tonal, with a main frequency dependent on ice properties) and melting (continuous, broadband sound with high frequencies, sometimes lasting for hours34), but they are generally less loud than the 10-dB threshold chosen here. A full identification of ice sounds in the present dataset is beyond the scope of this study, which focused on man-made sounds, but it should provide useful information about the effects of climate change in Cambridge Bay.

Some marine animals, like narwhals or seals, are known to vocalise at frequencies sometimes overlapping the MSFD bands. Although the aural identification of loud sounds in May and August 2018 (Fig. 8) does not show any, these sounds might still be present in other months, if longer than 1 min and loud enough. Anthropophony is however the predominant contributor to the louder sounds in these measurements.

Human-made sounds include those from ships large enough to have an AIS transponder. In and around Cambridge Bay, they are cruise and passenger ships, general cargo and offshore supply ships, and chemical tankers, all in small numbers. In summer, smaller ships are audible, including at frequencies beyond the MSFD “shipping bands” into the kHz range. These observations match those of other studies of coastal environments37,41,42. Some of these ships show constant sound levels, most likely because they are stationary in the harbour of Cambridge Bay. In summer, aircraft can occasionally be heard, although this is most likely modulated by their approach patterns, passing close above the ONC hydrophone, low enough to be readily detected. In winter, snowmobiles or All-Terrain Vehicles moving across the ice are a significant part of the underwater soundscapes (Table 1). The exact numbers are hard to ascertain, as the same vehicle might be heard several times depending on its route, and sometimes several vehicles can be heard together. This also matches anecdotal reports (e.g. snowmobile races during the local spring festival in May) and community observations of marine transportation18. Along with machinery sounds, they form an important broadband contribution to the louder sounds in winter.

Quantifying the impacts of human-made sounds onto the underwater soundscape of Cambridge Bay requires the assessment of frequencies beyond the “shipping bands” as well as the definition of baseline levels, as also recommended by Halliday et al.51. Both endeavours should consider all months, because of the variations in ice cover and sound types. This study used the months of May (fullest extent of ice cover, no shipping) and August (little to no ice, presence of shipping) to contrast the Arctic winter and summer seasons. Loud sounds will vary as the ice fractures and melts, with different frequency ranges, and as it reforms after summer. The amounts of local shipping also vary from year to year, depending on ice cover in particular (affected by climate changes). These variations will affect the baseline levels, which might vary with the months (or with the seasons). The exact frequency ranges might also vary with the months/seasons, as different anthropogenic sources need considering (e.g. snowmobiles in winter vs. small and large ships in summer).

This extension to other frequencies, possibly varying with time of year, will affect modelling of future impacts. Martin et al.49 showed the progress in modelling shipping sounds but also the current limits, in particular in shallow waters. Accurate identification of ship types and paths is important. AIS measurements have been very useful in areas like the North Sea44,45 and to model potential impacts of ships with known source levels in areas such the NE Atlantic46 and across the Arctic47. But recent studies48,52 show that AIS is not always working, either because of technical issues (in the Arctic, this would include satellite access at these high latitudes) or because of intention. Trafficking, smuggling and IUU (Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated) fishing are not currently perceived as an issue in the Arctic52. Another important input to these models is the frequency signature of the different vessels. Information is more readily available for the larger, commercial ships, travelling mostly along shipping lanes46. There is emerging data about smaller vessels (generally without AIS) frequenting shallower, coastal areas42,43,53,54 but these signatures will also depend on specific ship attributes, like speed of travel and general state48,55. In Arctic waters, this is compounded by the lack of knowledge of the water column at the exact times and ranges of interest, affecting models of sound propagation.

In summary, long-term acoustic measurements from the Cambridge Bay Community Observatory operated by Ocean Networks Canada were used to quantify the variations of the “shipping bands” recommended by the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive, from season to season and from year to year, between 2015 and 2024. They were also used to quantify the frequency content of loud and continuous events. Acoustic data was supplemented with measurements of local weather, local and regional ice cover, satellite-tracking of ships (using AIS) and aural identification of specific events. For simplicity, we focused on the months of May (full and continuous ice cover, no shipping) and August (no ice but shipping).

How do the MSFD “shipping bands” fare in polar environments? We showed that they can be equally loud in both open-water and ice-covered months, in spite of the obvious difference between potentially contributing sound sources (ships vs. no-ships). In summer, levels in the 63-Hz are generally lower than in the 125-Hz band, an observation often made when smaller vessels are present. In winter, both bands are at generally similar levels. Year-to-year variations do not show any particular trend, in particular from climate change effects.

Which human activities (other than shipping) could contribute to the underwater soundscape? Large ships (AIS-tracked) are few in numbers but acoustic measurements reveal much larger numbers of small vessels (with no AIS capability). In winter, the sounds from ships are replaced with the sounds from snowmobiles and ATVs. In both seasons, aircraft contribute to the underwater soundscapes, along with the sounds of machinery (either off- or near-shore). The acoustic impacts to consider must therefore include a large variety of sources, depending on seasons.

Events that are loud ( > 10 dB above the weekly SPL) and continuous (lasting more than 1 min) show strong contributions at frequencies above 50 Hz, with marked seasonal differences. The frequencies most representative of loud events extend well above 1 kHz in open-water season whereas they do not extend beyond 1 kHz at the maximum extent of ice cover. These variations also affect the baseline levels for human impacts, which might vary with the months (or with the seasons).

Are satellite records of shipping (using AIS) enough to assess and/or model human contributions to underwater soundscapes? The answer is clearly negative. In summer, more ships can be heard than are tracked by AIS. In winter, the absence of ships does not preclude important soundscape contributions from other vehicles like snowmobiles. More information is necessary on the acoustic characteristics of the different sound contributors. To model acoustic propagation underwater, more information is also necessary about the local conditions at each time period (water column properties, ice cover and ice type).

The European Marine Strategy Framework Directive and its criteria for Good Environmental Status (related to third-octave bands centred on 63 Hz and 125 Hz) are very good examples of how to monitor and ultimately manage anthropogenic impacts on underwater soundscapes. But they are not adapted to Arctic conditions like in the shallow-water environment of Cambridge Bay. MSFD guidelines, and any guidelines to be developed for and used in Arctic regions, need to address the presence of ice, its thickness and extent, with distinct assessments depending on the seasons. These guidelines need to incorporate the contribution of smaller vessels and other sources of sounds like snowmobiles on ice. The results from Cambridge Bay show for example that frequencies should be considered well above 1 kHz in open-water season but below 1 kHz at the maximum extent of ice cover.

The effort to “go beyond the shipping bands” and define adequate baselines is particularly pressing as climate change and geopolitical challenges are bound to greatly increase access to the Arctic and its marine (and terrestrial) resources. As pointed out by Halliday et al. (2020), the Arctic currently has very low ambient sound levels, and its marine life will therefore be more sensitive to any increase. Measurements in these remote and challenging regions need to include a variety of environments, from the High Arctic to transcontinental shipping lanes and coastal communities, with variable ice cover and other sound sources than just large vessels. As demonstrated at lower latitudes48, underestimating current impacts and their developments will lead to inadequate policies, management and mitigation efforts. It is therefore increasingly urgent to define an “Arctic Marine Strategy Framework Directive”.

Method

Acoustic data processing

Ambient sounds are measured at the Cambridge Bay Community Observatory operated by Ocean Networks Canada24 using an Ocean Sonics icListen HF hydrophone positioned 8 m deep (for a mean water depth of 13 m). Measurements from the months of May and August 2015 to 2024 were downloaded in lossless audio formats WAV and FLAC. They were sampled at 64 kHz and recorded with 24-bit depths. There were some gaps in data coverage, due to occasional instrument issues and the effects of COVID lockdowns on data recovery. The processing was done with PAMGuide56, using the hydrophone sensitivity of -170 dB re. 1 V/μPa and the frequency range of 10 Hz – 32 kHz. Time windows of 1 second, with a Hann filter and 50% overlap, were used to calculate broadband sound pressure levels (SPLs), power spectral densities (PSDs) using Welch’s method and third-octave band levels (TOLs), aggregated every 5 min.

We defined as “loud, continuous event” any series of measurements where the SPL exceeded the weekly mean SPL, centred on the event, by at least 10 dB for a continuous duration of at least 1 min (filtering out most ice-related processes but keeping most anthropogenic sound sources like ships).

Measurements of ice cover

To assess the impact of shipping on soundscapes, we wanted to compare times with more shipping (when there is less to no ice) and times without shipping (when ice cover is maximum). Local ice cover is measured with an ice profiler, operated by ONC, showing ice thickness close to the hydrophone (with a few data gaps, in particular in spring 2021). Regional ice cover is available from weekly ice charts provided by the Canadian Ice Service (https://iceweb1.cis.ec.gc.ca/Archive/page1.xhtml), showing amounts of ice cover and ice types. They are based on analysis and integration of data from satellite imagery, weather and oceanographic information, and visual observations from ship and aircraft.

Weather information

Wind speeds and air temperatures were measured hourly at neighbouring weather station Cambridge Bay A (69°06'29“N; 105°08'14“W, WMO ID:71925), currently operated by NAV Canada. The records were downloaded from the Canadian Government website https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html. They were converted to the same time zone as the ONC acoustic measurements. Times with no acoustic measurements were omitted. The mean sound levels in each third-octave band were correlated with wind speeds for every hour using the Pearson correlation, in line with similar calculations5, as an indicator of Sea State. Hourly temperatures and their first derivatives were used to assess possible changes in ice dynamics.

Satellite tracking of shipping

Ship traffic information is provided by the Arctic Ship Traffic Database (ASTD) of the Arctic Council’s working group on Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME), using the Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). ASTD Level 3 data includes ship position (every 6 min), ship type and activity, extracted for the area within the line of sight of Cambridge Bay. The number of AIS entries for each month gives a strong indication of how much traffic was in Cambridge Bay, even if the number of unique ships might be small and they might be re-entering the area several times. The number of days with shipping in each month indicates how busy it was overall. Over the years, AIS records show the main categories present around Cambridge Bay include cruise and passenger ships, general cargo and offshore supply ships, and chemical tankers. These records are however limited to AIS-using ships.

Data Availability

The acoustic data that support this study are available from the Oceans 3.0 Data Portal of Ocean Networks Canada ([https://data.oceannetworks.ca/home)). Local ice cover is available from the Ocean 3.0 Data Portal. Regional ice data is provided by the Canadian Ice Service ([https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/ice-forecasts-observations/latest-conditions/products-guides/chart-descriptions.html)). Wind speeds from the Cambridge Bay A weather station were downloaded from the Canadian Government website [https://climate.weather.gc.ca/historical_data/search_historic_data_e.html). The AIS records of ship types and movements are available from the Arctic Ship Traffic Database (ASTD), coordinated by the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) Working Group of the Arctic Council ([https://pame.is/ourwork/?it=projects/arctic-marine-shipping/astd)).

References

Zhou, W., Leung, L. R. & Lu, J. Steady threefold Arctic amplification of externally forced warming masked by natural variability. Nat. Geosci. 17, 508–515 (2024).

Moon, T. A., Druckenmiller, M. L. & Thomas, R. L. (eds.), Arctic Report Card 2024 – Executive Summary, NOAA technical report OAR ARC 24-01, https://doi.org/10.25923/b7c7-6431 (2024).

Cheng, L. et al. Record High Temperatures in the Ocean in 2024. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 42, 1092–1109 (2025).

Dingwall, J. T. et al. The Arctic marine soundscape of the Amundsen Gulf, Western Canadian Arctic. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 204, 116510 (2024).

Bonnel, J., Kinda, G. B. & Zitterbart, D. P. Low-frequency ocean ambient noise on the Chukchi Shelf in the changing Arctic. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 149, 4061–4072 (2021).

Dekeling, R., Tasker, M., Ferreira, M. & Zampoukas, N. (eds) Monitoring Guidance for Underwater Noise in European Seas, Part I: Executive Summary, JRC Scientific and Policy Report EUR 26557 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, https://doi.org/10.2788/29293 (2014).

Merchant, N. D. et al. A decade of underwater noise research in support of the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. Ocean Coast. Manag. 228, 106299 (2022).

Dekeling, R. P. A. et al., Monitoring Guidance for Underwater Noise in European Seas - Executive Summary, 2nd Report of the Technical Subgroup on Underwater Noise (TSG Noise), https://www.cbd.int/doc/meetings/mar/mcbem-2014-01/other/mcbem-2014-01-submission-msfd-03-en.pdf (2013).

Collins, M. D., Turgut, A., Menis, R. & Schindall, J. A. Acoustic recordings and modeling under seasonally varying sea ice. Sci. Rep. 9, 8323 (2019).

Chotiros, N. P. Simulation of under-ice acoustic propagation loss due to ice keels. Proc. OCEANS 2023, 1–5 (2023).

Hildebrand, J. A. Anthropogenic and natural sources of ambient noise in the ocean. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 395, 5–20 (2009).

Ainslie, M. A., Andrew, R. K., Howe, B. M. & Mercer, J. A. Temperature-driven seasonal and longer-term changes in spatially averaged deep ocean ambient sound at frequencies 63–125 Hz. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 149, 2531–2545 (2021).

Jalkanen, J.-P., Johansson, L., Andersson, M. H., Majamäki, E. & Sigray, P. Underwater noise emissions from ships during 2014–2020. Environ. Pollut. 311, 119766 (2022).

Stephenson, S. R. & Smith, L. C. Influence of climate model variability on projected Arctic shipping futures. Earth’s Future 3, 331–343 (2015).

Melia, N., Haines, K. & Hawkins, E. Sea ice decline and 21st century trans-Arctic shipping routes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 9720–9728 (2016).

Dawson, J., Pizzolato, L., Howell, S. E. L., Copland, L. & Johnston, M. E. Temporal and Spatial Patterns of Ship Traffic in the Canadian Arctic from 1990 to 2015. Arctic 71, 15–26 (2018).

Mannherz, F., Knol-Kauffman, M., Rafaly, V., Ahonen, H. & Kruke, B. I. Noise pollution from Arctic expedition cruise vessels: understanding causes, consequences and governance options. npj Ocean Sustain 3, 51 (2024).

Carter, N. A. et al. Arctic Corridors and Northern Voices: governing marine transportation in the Canadian Arctic (Cambridge Bay, Nunavut community report), University of Ottawa, https://doi.org/10.20381/RUOR37325 (2018).

Bagger, A. M. T., Blockley, D., Gustavson, K., Mosbech, A. & Zinglersen, K. B., Marine mining in Greenland - A strategic assessment of potential impacts, Aarhus University, Danish Centre for Environment and Energy, Scientific Report No. 640 https://dce.au.dk/fileadmin/dce.au.dk/Udgivelser/Videnskabelige_rapporter_600-699/SR640.pdf (2025).

Kochanowicz, Z. et al. Using western science and Inuit knowledge to model ship-source noise exposure for cetaceans (marine mammals) in Tallurutiup Imanga (Lancaster Sound), Nunavut, Canada. Mar. Policy 130, 104557 (2021).

Godin, P. & Daitch, S. (eds), Proceedings of the Workshop: Arctic Mining: Environmental issues, mitigation and pollution control for marine and coastal mining, Arctic Council’s Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment (PAME) Working Group, https://pame.is/images/03_Projects/Mining/Arctic_Mining_-_Environmental_Issues_-_Proceedings_of_the_Workshop_June_2023.pdf (2023).

Riisager-Simonsen, C. & Stedmon, C. (eds.), Ocean Decade - Arctic Action Plan, Danish Center for Marine Research”, https://backend.orbit.dtu.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/279078829/Ocean_Decade_AAP_version_H_1_1_.pdf (2021).

DFO, Evaluation of a Proposed Approach for Offsetting Increases in Underwater Noise from Marine Shipping, Using Information on Southern Resident Killer Whales. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Sci. Advis. Rep. 2025/001 (2025).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2014-09-26, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/cedce586-98c7-4548-afb6-beace76fd486 (2014).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2017-09-14, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/b195c0a6-8249-4665-8a15-30992ac39bbc (2017).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2018-07-26, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/76b96820-c9fa-44a3-9d34-d7c08f887a18 (2018).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2019-08-01, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/c866e384-2bc3-49d2-ac60-e590f355d77a (2019).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2021-09-15, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/b8535f9f-fe6a-4c97-8bca-b6abddfbcbe1 (2022).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2022-09-12, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/d8c4bbc8-f9ab-4591-bc9c-996281aaba58 (2023).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2023-08-03, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/cfa875d8-8f0a-470e-aedd-bda1924d28e2 (2023).

Ocean Networks Canada Society, Cambridge Bay Hydrophone Deployed 2024-08-29, Ocean Networks Canada Society, https://doi.org/10.34943/59a7863e-3c15-4d62-93fa-4f9717e04582 (2024).

Halliday, W. D., Underwater noise from ship traffic near Cambridge Bay, Nunavut in 2017 and 2018. Report written for Transport Canada, Wildlife Conservation Society, Canada, https://wcscanada.org/resources/underwater-noise-from-ship-traffic-near-cambridge-bay-nunavut-in-2017-and-2018-report-written-for-transport-canada (2021).

Blondel, Ph., Bichan, F., Lewry, L., Hallett, H. & McCarthy, G. Acoustic properties of Arctic sea ice, from year-long underwater measurements in Cambridge Bay, Canada, Proc. International Conference on Underwater Acoustics (ICUA) (2022).

Mahanty, M. M. et al. Underwater sound to probe sea ice melting in the Arctic during winter. Sci. Rep. 10, 16047 (2020).

Buckingham, M. J., Giddens, E. M., Simonet, F. & Hahn, T. R. Propeller noise from a light aircraft for low-frequency measurements of the speed of sound in a marine sediment. J. Comp. Acoust. 10, 445–464 (2002).

Cook, E., Winters, J., Anthony, K., Barclay, D. R. & Oliver, E. Determining the speed dependent source level of a snowmobile traveling on sea-ice. J. Acoust. Soc. Am 152, A72 (2022).

Garrett, J. K. et al. Long-term underwater sound measurements in the shipping noise indicator bands 63 Hz and 125 Hz from the port of Falmouth Bay, UK. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 110, 438–448 (2016).

Mustonen, M. et al. Spatial and temporal variability of ambient underwater sound in the Baltic Sea. Sci. Rep. 9, 13237 (2019).

Hermannsen, L., Beedholm, K., Tougaard, J. & Madsen, P. T. High frequency components of ship noise in shallow water with a discussion of implications for harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena). J Acoust Soc Am 136, 1640–1653 (2014).

Erbe, C. Modeling Cumulative Sound Exposure Over Large Areas, Multiple Sources, and Long Durations. The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life 730, 477–479 (2012).

Rako, N. et al. Leisure boating noise as a trigger for the displacement of the bottlenose dolphins of the Cres-Lošinj archipelago (northern Adriatic Sea, Croatia). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 68, 77–84 (2013).

Picciulin, M. et al. Are the 1/3-Octave Band 63- and 125-Hz Noise Levels Predictive of Vessel Activity? The Case in the Cres–Lošinj Archipelago (Northern Adriatic Sea, Croatia). The Effects of Noise on Aquatic Life II 875, 821–828 (2016).

Wladichuk, J. L., Hannay, D. E., MacGillivray, A. O., Li, Z. & Thornton, S. J. Systematic source level measurements of whale watching vessels and other small boats. J. Ocean Tech. 14, 110–126 (2019).

Sertlek, H. Ö, Slabbekoorn, H., Ten Cate, C. & Ainslie, M. A. Source specific sound mapping: Spatial, temporal and spectral distribution of sound in the Dutch North Sea. Env. Poll. 247, 1143–1157 (2019).

Putland, R. L., De Jong, C. A. F., Binnerts, B., Farcas, A. & Merchant, N. D. Multi-site validation of shipping noise maps using field measurements. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 179, 113733 (2022).

Farcas, A., Powell, C. F., Brookes, K. L. & Merchant, N. D. Validated shipping noise maps of the Northeast Atlantic. Sci. Total Environ. 735, 139509 (2020).

Heaney, K. D., Verlinden, C. M. A., Seger, K. D. & Brandon, J. A. Modeled underwater sound levels in the Pan-Arctic due to increased shipping: Analysis from 2013 to 2019. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 155, 707–721 (2024).

Hague, E. et al. AIS data underrepresents vessel traffic around coastal Scotland. Mar. Policy 178, 106719 (2025).

Martin, S. B. et al. Verifying models of the underwater soundscape from wind and ships with benchmark scenarios. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 156, 3422–3438 (2024).

Ainslie, M. A. Principles of Sonar Performance Modeling, Springer: New York (2010).

Halliday, W. D., Pine, M. K. & Insley, S. J. Underwater noise and Arctic marine mammals: review and policy recommendations. Environ. Rev. 28, 438–448 (2020).

Welch, H. et al. Hot spots of unseen fishing vessels. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq2109 (2022).

Svedendahl, M., Andersson, M., Lalander, E. & Sigray, P. Underwater acoustic source signatures from recreation boats—Field measurement and guideline, Swedish Defence Research Agency, Technical Report No. FOI-R–5115–SE (2021).

Johansson, A. T., Lalander, E., Krång, A. S. & Andersson, M. Speed dependence, sources, and directivity of small vessel underwater noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 156, 2077–2087 (2024).

de Jong, K. et al. Trade-offs and synergies in the management of environmental pressures: a case study on ship noise mitigation. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 218, 118073 (2025).

Merchant, N. D. et al. Measuring acoustic habitats. Meth. Ecol. Evol 6, 257–265 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Ocean Networks Canada for their open-access provision of acoustic measurements and ancillary data. Access to the Arctic Ship Traffic Database was funded by the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology, as part of the United Kingdom - Arctic Council Working Groups – Research and Engagement Scheme 2024/25, working with the Arctic Council Working Groups, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the NERC Arctic Office.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.B.: conceptualisation, data curation, formal analyses (lead), visualisation, supervision and validation, writing (original draft and lead). R.B. and D.C. : formal analyses, visualisation and data curation (acoustic data), writing (review). R.B. and D.C. were final-year undergraduate students doing their research project under the supervision of P.B.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Blondel, P., Belcher, R. & Cooper, D. Marine soundscapes of the Arctic and human impacts: going beyond the “shipping bands”. npj Acoust. 2, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00038-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44384-025-00038-1