Abstract

This study focuses on the development of an electrospun Poly Lactide-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) scaffold for ocular surface regeneration, specifically for the treatment of Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency (LSCD). The scaffold is designed to support the attachment, proliferation, and maintenance of induced pluripotent stem cell-derived limbal stem cells (iPSC-LSCs). To address the hydrophobic nature of PLGA and enhance biocompatibility, the scaffold surface was functionalized with extracellular matrix proteins, specifically Collagen IV and Laminin-521, through atmospheric plasma treatment. Micro-perforations were introduced using laser cutting to improve transparency and membrane permeability. Results indicate that Laminin-521 is essential for iPSC-LSC attachment and survival, with enhanced expression of LSC stemness markers and corneal epithelial differentiation markers observed on the functionalized scaffold. These findings suggest that this scaffold can serve as a viable platform for iPSC-LSC transplantation. Future work will focus on refining scaffold design parameters and conducting in vivo studies to assess therapeutic efficacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cornea, a transparent, avascular tissue located at the front of the eye, is fundamental to vision due to its role in refracting light and acting as a protective barrier1. It consists of five layers, including the epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium, with the outermost epithelium being in constant turnover, maintained by a unique population of unipotent stem cells called limbal stem cells (LSCs). These LSCs reside in the limbus, bordering the corneal circumference, separating the cornea from the conjunctiva, and are essential for the regeneration of the corneal epithelium2,3. Damage to these LSCs, either through chemical burns, infections, or autoimmune disorders, leads to a condition known as Limbal Stem Cell Deficiency (LSCD), which severely impairs corneal regeneration. LSCD results in a range of complications, including corneal opacification, vascularization, and scarring, all of which culminate in visual impairment or complete blindness4,5,6. Precise epidemiological data about LSCD is limited, and due to regional variability makes it challenging to establish accurate disease prevalence rates. Specialized referral cornea practice U.S. center has reported encountering LSCD in approximately 4.25% of patients seen for ocular surface disorders7.

LSCD presents a significant clinical challenge, as the body is unable to regenerate the corneal epithelium without functional LSCs, and this leads to persistent epithelial defects. The loss of a functional limbal region disrupts its barrier function, allowing conjunctival epithelial cells to invade the normally clear, avascular cornea. This results in conjunctivalization, neovascularization, scarring, and an irregular ocular surface, leading to significant vision impairment and potential blindness. One of the most promising treatment strategies for LSCD is the transplantation of healthy LSCs to restore corneal surface integrity5,6,8,9,10. Healthy LSCs can be either obtained from the patient’s own healthy eye (in cases of unilateral LSCD) or from donor tissue (in bilateral cases). However, this therapeutic approach hinges on the development of a suitable carrier or scaffold to deliver these cells to the affected cornea. The scaffold must not only provide structural support but also offer an environment conducive to cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation. Currently, biological scaffolds derived from natural tissues, such as amniotic membrane, collagen, or fibrin, are commonly employed in clinical settings. While these materials exhibit good biocompatibility and have been successfully used in corneal regeneration, they present several limitations, including batch-to-batch variability due to their biological origin, limited supply, and the potential for immune rejection. Moreover, biological scaffolds often lack tunable mechanical properties, which may compromise their ability to mimic the native limbal niche or support long-term stem cell function. For example, amniotic membrane’s inconsistent degradation rate can necessitate additional surgeries. These drawbacks have increased interest in synthetic or bioengineered alternatives. PLGA was selected over ophthalmic materials commonly used in contact lenses (e.g., hydrogels, PMMA) because it offers a degradable, mechanically supportable fibrous architecture that can be electrospun to mimic basement-membrane-like topography. Also, PLGA permits control of support duration via lactide:glycolide ratio. On the other hand, non-degradable PMMA and many lens-grade hydrogels lack tunable degradation and tend to provide limited structural reinforcement for transplant handling. These attributes made PLGA a suitable platform for a temporary, bioactive carrier11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

This study focuses on the development of a synthetic scaffold designed to address the limitations associated with existing biological carriers and to provide a reliable platform for LSC transplantation in the treatment of LSCD and other ocular surface disorders. The scaffold is based on Poly Lactide-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA), a biodegradable and biocompatible polymer that has been widely studied in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. PLGA is attractive for this application due to its adjustable degradation rate, mechanical stability, and ease of processing. Its degradation rate can be tailored by altering the ratio of lactide to glycolide, which allows for precise control over the duration of scaffold support in vivo18,19,20,21,22,23.

The fabrication of the scaffold is achieved through electrospinning, a versatile technique utilized high voltage to generate nano/microscale-dimension materials with a high surface-area-to-volume ratio. The porous and interconnected fibrous network produced by electrospinning can emulate the topography of the extracellular matrix (ECM) fibrils, providing a suitable 3D environment for cell growth and organization. The tailoring of fibrous structure and surface chemistry can be altered to promote cell proliferation and attachment, which are crucial for tissue repair and regeneration. Furthermore, the scaffold’s porous architecture facilitates efficient diffusion of nutrients and removal of waste products, thereby maintaining cell viability. In the case of ocular surface regeneration, the nanofibrous structure of the scaffold provides a biomimetic environment that can promote the adhesion and proliferation of LSCs, facilitating corneal epithelial repair18,19.

Despite its favorable mechanical properties and biodegradability, PLGA is inherently hydrophobic and lacks the bioactive cues such as cell-adhesive motifs, growth factor-binding domains, and matrix-derived signaling peptides necessary for optimal cell-material interactions. These characteristics can limit the scaffold’s ability to support cell adhesion and proliferation, particularly for sensitive cell types such as LSCs. To address these limitations, surface functionalization techniques are employed to modify the scaffold and enhance its biocompatibility. In this study, we functionalize the PLGA scaffold with ECM proteins, specifically Collagen IV and Laminin-521, both of which play critical roles in maintaining the stem cell niche in the limbus. Collagen IV is a key structural component of the basement membrane, while Laminin-521 is known to support stem cell adhesion, survival, and differentiation24,25. Plasma treatment is widely used to modify polymer surfaces by introducing functional groups such as amino and carboxyl, enhancing the covalent attachment of bioactive molecules without affecting bulk material properties26. This surface functionalization improves the stability and bioactivity of immobilized proteins and enzymes, making it especially advantageous for biomedical applications. Recent research has indicated that plasma-treated surfaces significantly enhance the durability of binding for bioactive molecules, thereby improving the performance and longevity of biomaterials under physiological conditions27,28. In our case, by immobilizing the proteins mentioned above onto the scaffold surface, we aim to replicate the microenvironment of the limbal niche, providing bioactive sites that promote the attachment and maintenance of LSCs.

Another critical consideration in the design of a scaffold for ocular surface regeneration is transparency. Since the cornea is responsible for transmitting and focusing light, any scaffold used in its repair must maintain a high degree of optical clarity. Traditional electrospun scaffolds, while highly porous, are not inherently transparent due to the random arrangement of fibers, which can scatter light and reduce transmittance18,29. To overcome this issue, we incorporated micro-scale perforations into the electrospun PLGA scaffold using a picosecond laser cutting technique. This method allows for the precise creation of micro-pores without causing significant damage to the surrounding scaffold structure.

The goal of this study is to evaluate the efficacy of the surface-modified electrospun PLGA scaffold in supporting the attachment, proliferation, and differentiation of iPSC-derived LSCs (iPSC-LSCs) in vitro. iPSC-LSCs offer several advantages over traditional donor-derived LSCs, including the potential for autologous transplantation, which eliminates the risk of immune rejection, as well as the ability to generate large numbers of cells for therapeutic use. Furthermore, iPSCs can be derived from the patient’s own cells, paving the way for personalized medicine approaches to ocular surface regeneration30,31,32.

Results

The schematic illustration of the experimental process is shown in Fig. 1.

Morphology and optical properties of scaffold

Through successful optimization of electrospinning properties, electrospun membranes of consistent fiber diameter with random orientation were obtained (Fig. 2A). Scaffold characterization from SEM images reveals an average fiber diameter of 1.757 + 0.20 μm. After fabrication of the electrospun membrane, perforations were introduced using a picosecond laser cutter. The holes were introduced with minimal damage to the scaffold with desired diameter and spacing. The electrospun scaffolds were successfully perforated with holes of 200 μm and with varying distance of 100 μm (Fig. 2B) or 50 μm (Fig. 2C) between them. These perforations improve visibility as can be seen from the digital photograph when compared with non-perforated PLGA scaffold (Fig. 2D–F). Visible light absorption spectra observed using microplate, shows that decreasing distance between perforations improved light transmittance from 44 ± 0.14% to 60 ± 0.15% (Fig. 2G).

Surface characterization of scaffold

From the TOF-SIMS analysis, we observed that atmospheric plasma treatment enhanced the uniformity and density of Col-IV coating on PLGA scaffolds compared to untreated controls (Fig. 3A). The homogeneous distribution of Col-IV, as indicated by ToF-SIMS, suggested improved surface properties conducive to cell adhesion and interaction. To further validate the spatial distribution and preservation of bioactive epitopes of the adsorbed Col-IV, immunofluorescence staining was conducted (Fig. 3B). Immunofluorescence results supported the ToF-SIMS findings, confirming that atmospheric plasma treatment effectively promoted the adsorption and retention of Col-IV on the scaffold surface. This method not only enhanced surface coverage but also maintained the integrity and bioactivity of Col-IV, critical for subsequent cellular recognition and response.

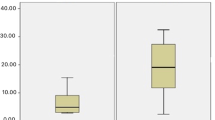

Viability and proliferation of iPSC-LSCs on scaffold

We compared the ability of electrospun PLGA scaffolds with different surface treatments to support iPSC-LSC adherence, viability, and proliferation. After 24 h, a viable cell population was observed on samples that were plasma-treated and coated with Ln-521 and both Ln-521 + Col-IV (Fig. 4A). For other plain and surface treatment conditions of PLGA, some iPSC-LSC adhered to the substrates, but many were stained as dead cells. From day 3 onward, these conditions resulted in iPSC-LSCs detached from the substrates or being mostly stained as dead cells, indicating their inability to support iPSC-LSC maintenance. Whereas samples that were plasma-treated and coated with Ln-521 and both Ln-521 + Col-IV could sustain iPSC-LSC culture for at least 7 days. A similar trend was observed when the metabolic and proliferation activity of iPSC-LSCs was observed and quantified using an alamarBlue assay (Fig. 4B). Compared to all other conditions, plasma treated and coated with Ln-521 had the highest metabolic activity. Specifically, compared to Ln-521 coated TCP on Day 3 (p < 0.001), Day 5 (p < 0.0001), and Day 7 (p < 0.0001), there was significantly higher metabolic activity for plasma treated and coated with Ln-521. Plasma-treated and coated with both Ln-521 + Col-IV also had higher metabolic activity compared to Ln-521-coated TCP. In light of these results, subsequent in vitro experiments were performed only on electrospun PLGA substrates that were plasma-treated and coated with Ln-521 and both Ln-521+Col-IV without any perforations.

A Live/Dead staining of iPSC-LSC where alive cells are shown in green and dead cells are in red. Representative images shown here. Scale bar: 275 µm. B Proliferation of iPSC-LSC on scaffolds at different time points. The error bars represent SEM and **** denotes statistical significance at p < 0.0001 between the control and PLGA-Plasma treated+Ln-521 at each timepoint using two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test.

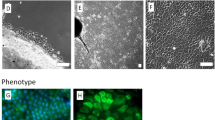

Morphology of iPSC-LSC on PLGA

Morphology of iPSC-LSCs was analyzed using both phalloidin staining and SEM imaging. In all culture conditions, iPSC-LSCs exhibited a tightly packed, cobblestone-like epithelial morphology and exhibited an extensive, well-organized network of actin filaments interconnecting adjacent cells (Fig. 5A). Compared to Ln-521 coated TCP, iPSC-LSCs cultured on PLGA surfaces appeared smaller. SEM imaging (Fig. 5B) after 7 days of culture further demonstrated that iPSC-LSCs established confluent, multilayered sheets with strong adherence to the plasma-treated PLGA substrates.

Stemness and commitment towards corneal epithelial lineage iPSC-LSC on scaffold

Finally, we investigated whether iPSC-LSC cultured on surface functionalized PLGA can maintain their stemness and their commitment towards corneal epithelial lineage. The expression of several LSC markers were evaluated through immunocytochemistry (Fig. 6). iPSC-LSCs after 7-day culture on both surface modified PLGA and Ln-521 coated TCP strongly expressed markers related to stemness and used to identify LSCs (ΔNp63, ABCG2, PAX6). Faint and very low levels of CK12 were detected in all conditions. Analysis of relative gene expression reveals that compared to Ln-521 coated TCP, there was upregulation of LSC stemness markers P63, ABCG2, and CK14 on electrospun scaffolds (Fig. 7). There was also upregulation in gene expression of CK3 and IVL, markers related to corneal epithelial differentiation and maturation on scaffolds surfaces compared to Ln-521 coated TCP. However, there was downregulation in expression of ABCB5 and CEBPd on scaffolds surfaces compared to Ln-521 coated TCP.

Discussion

In this study, we developed the optimal biomaterial that fulfills all the scaffold design essential properties required for ocular surface regeneration18,19. Randomly oriented porous nanofibrous structure obtained through electrospinning mimics the topography of basement membrane of corneal epithelium providing them with topographical cues similar to native conditions18. Based on prior literature findings we used PLGA due to its bulk structure properties, which mimics the native ECM architecture of limbal region consistently and has been used in FDA-approved devices for various clinical uses33. The native ECM architecture of the limbal region is a spatially organized, interwoven network of collagen fibrils (types IV) and laminin isoforms (e.g., laminin-521) arranged into a stratified, anisotropic matrix that mechanically stabilizes LSCs while facilitating nutrient diffusion and signaling. Prior findings show electrospun scaffolds from PLGA could support growth of LSCs and have been used in clinical trials20,23,34. Degradation and other mechanical properties can also be changed by controlling the lactic acid/glycolic acid ratio. Usually, to improve transparency and biocompatibility of a scaffold, a synthetic polymer is blended with natural polymers such as collagen. However, this increases the variability in scaffold properties as seen in our previous studies35. We wanted to create scaffolds using only a synthetic polymer and we were able to get more consistent and uniform fiber diameters in this study, we introduced micro-perforations on the scaffold membrane which improved light transmittance up to 60% (Fig. 2G). This value is less than light transmittance of native cornea which ranges from 80 to 94%36. Still, this suggests application of surface-modified scaffolds will not obstruct vision when used as a graft. Prior studies have shown that perforations can provide an additional layer of control on the mechanical and degradation properties of the developed scaffold while keeping the polymer and fabrication parameters consistent22. In our scaffolds, a major portion of the nanofiber matrix remains intact to support cell adhesion. While some migration through pores is possible, we predict most cells will remain localized on the seeded surface even though this interaction was not evaluated in this study as it focused on more on functionalizing scaffold and watch its effect on iPSC-LSC. This is consistent with prior reports where porous membranes aided nutrient and oxygen exchange without significantly disrupting cell localization during transplantation (20, 22, 23).

One of the drawbacks of using synthetic polymers such as PLGA is low cellular attachment due to its hydrophobic nature and low surface energy37. Atmospheric plasma treatment provides quick and efficient method of functionalizing the surface of electrospun PLGA with ECM proteins without affecting the bulk properties. One study demonstrated that XPS analysis revealed oxygen plasma treatment of PLGA nanofibers slightly increased the O/C ratio and significantly enhanced C–O bonding; indicative of hydroxyl or peroxyl group formation which improves surface hydrophilicity and enables biomolecule attachment38. In our study, we also observed that after the plasma treatment and protein mobilization, TOF-SIMS detected the fragment characteristics of protein side chains (-CNO). The spatial distributions of these signals are absent or minimal in untreated PLGA but consistently prominent in treated samples, confirming successful protein immobilization and enhanced attachment of bioactive molecules (Fig. 3). Due to the relatively low density of laminin (0.5 µg cm−2) deposition compared to collagen-IV (5 µg cm−2), TOF-SIMS detection was not feasible in our setup. While immunostaining was attempted, the signal intensity was not strong enough for reliable imaging. Also, comparison of protein adhesion on surface was determined qualitatively instead of using a quantitative measure which is a limitation of this study.

Adult stem cells, such as LSCs, are typically sensitive to their surrounding microenvironment, residing in a specialized niche where ECM proteins crucially regulate stemness and cellular activity39,40,41. This study explored Col-IV, an important ECM protein prevalent in the limbal niche with additional LN-521 to determine their effects on iPSC-LSCs. Our findings revealed that LN-521 was essential for supporting the attachment and survival of iPSC-LSCs on PLGA surfaces (Fig. 4). Both LN-521 alone and in combination with Col-IV effectively supported cell attachment and survival. This finding aligns with a prior study that used plasma-activated bacterial nanocellulose coated with Col-IV and Ln-52141. Prior studies have shown that LSCs maintained in the presence of LN-521 or LN-511 could be supported to adhere and proliferate without hampering stemness42. Neither plasma activation nor surface functionalization with only Col-IV could produce a favorable interaction between electrospun PLGA and iPSC-LSCs. The downward trend in metabolic signal over time likely reflects medium conditioning and known variability across iPSC-derived cultures over multi-day assays, rather than loss of scaffold support43,44.

Electrospun PLGA surfaces functionalized exclusively with Col-IV could not support iPSC-LSCs, an interesting finding considering that Col-IV is widely recognized as a critical ECM component in limbal niches and suggested to be one of the most prominent proteins within this microenvironment24,41,45. Col-IV is also considered essential for adhesion and maintaining the stemness of LSCs46. Additional studies are necessary to elucidate why Col-IV alone was insufficient for supporting iPSC-LSC attachment and survival. In our preliminary trials, an electrospun PLGA surface functionalized only with Col-IV performed significantly better than plasma-activated or plain electrospun PLGA scaffolds when seeded with a human corneal epithelial cell line (Celprogen, data not shown). To further examine this effect, Col-IV was also tested on tissue culture plastic (TCP), where iPSC-LSCs similarly failed to attach or survive. This discrepancy may suggest that preferences for adhesion moieties differ based on the differentiation state or maturation level of cells. Differentiated epithelial cells might possess broader or distinct ECM preferences compared to pluripotent stem cell-derived LSCs, likely due to differences in integrin expression profiles and reduced dependence on niche-specific signals. We also recognize that differences in adhesion between iPSC-LSCs and Celprogen cells may be related to culture adaptation of the latter, or to variability in enzymatic singularization of iPSC-LSCs prior to seeding, in addition to maturation state. Further investigation is warranted to confirm whether these preferences are specific to iPSC-LSCs relative to epithelial cell lines.

We also investigated the impact of surface functionalized electropsun scaffolds on iPSC-LSC phenotype and stemness. iPSC-LSCs showed their characteristic epithelial-like morphology and formed confluent cell sheets on the surface functionalized electropsun scaffolds. While these images suggest possible multilayer organization, more definitive confirmation will require 3D reconstruction of Z-stacked confocal images, which we highlight as an important next step for future studies. This indicates preference of iPSC-LSC for the developed substrate and its suitability to act as a carrier for transplantation. Immunofluorescence analysis showed robust expression of canonical stemness markers such as ΔNp63 and ABCG2, with only faint expression of CK12, a marker of terminally differentiated corneal epithelial cells. These findings were consistent with the expression patterns observed on LN521-coated TCP, suggesting that the scaffold supports a progenitor-like phenotype. At the gene expression level, iPSC-LSCs cultured on the functionalized electrospun scaffolds showed upregulation of ABCG2 and CK14 markers associated with stemness and basal epithelial identity. Simultaneously, there was increased expression of CK3 and IVL, which are indicative of early corneal epithelial differentiation and maturation. The expression of CEBPD, a marker linked to cellular quiescence, was downregulated compared to cells grown on LN521-coated TCP. Taken together, these results suggest that iPSC-LSCs maintained on surface-functionalized electrospun scaffolds are phenotypically heterogeneous. The expression profile reflects a dominant population of active LSCs, many of which appear to be transitioning into early transient amplifying cells (TACs), a state associated with regenerative activity rather than dormancy30,47. The distinct cytoskeletal organization and morphology observed on the nanofiber substrate, compared with TCP, further indicate that iPSC-LSCs may interact more favorably with the scaffold surface. This dynamic, yet stem-like phenotype supports the potential use of these scaffolds as effective carriers for ocular surface reconstruction therapies.

Looking forward, our future plan is to further refine the scaffold design by exploring additional parameters such as fiber stiffness, diameter, and topography, aiming to better mimic the native LSC niche. These physical characteristics are known to influence cell behavior and may enhance the scaffold’s ability to support iPSC-LSC maintenance and function; We also intend to develop more accurate in vitro models to test the scaffold’s performance under conditions that closely resemble the human ocular surface, such as air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures, co-culture systems with other limbal niche cells (e.g., limbal stromal or melanocyte populations), and dynamic flow models that simulate tear film shear stress. In parallel, future studies will incorporate quantitative image analysis, and functional assays such as barrier integrity testing to further strengthen reproducibility and translational relevance. Ethanol sterilization was used only for in vitro studies, and clinically appropriate sterilization methods (e.g., gamma irradiation, ethylene oxide) will be evaluated moving forward. Ultimately, preclinical animal studies will be essential to assess the in vivo efficacy of the scaffold in supporting corneal regeneration and restoring ocular surface integrity. Together, these future investigations will facilitate the optimization of a biomimetic, scalable scaffold platform for clinical application in LSCD and other corneal epithelial disorders.

In conclusion, this study represents a substantial advancement in the development of biomaterials for ocular surface regeneration, particularly in the treatment of LSCD. Previous research has focused on using primary LSCs on fibrous surfaces; however, this is the first study that examines iPSC-LSCs on an electrospun scaffold, opening new avenues for stem cell-based therapies. The electrospun PLGA scaffold developed in this study, with its enhanced surface properties through micro-perforations, plasma functionalization, and ECM protein coating, provides a more consistent and reliable platform for the attachment, proliferation, and maintenance of iPSC-LSCs compared to traditional natural scaffolds.

Method

Fabrication of nanofibrous PLGA scaffold

PLGA (50:50 ratio; Purasorb® PDLG 5010; Corbion Amsterdam, Netherlands) was used to make electrospun scaffolds. The electrospinning solution was created by dissolving PLGA (14% w/v) in 1,1,1,3,3,3-hexafluoro-2-propanol (HFIP) (H0424; TCI America, Portland, OR, USA) by overnight magnetic stirring. The following electrospinning conditions was used to collect nanofibers on the stationary copper shim collector: 15 cm needle collector distance; 20 G needle tip; 16 kV voltage applied to needle tip, flow rate of 4 mL/hr.

Laser perforation

The LPKF ProtoLaser R at the Northwestern University Atomic and Nanoscale Characterization Experimental Center (NUANCE) was used to make laser perforation in the electrospun scaffolds. These microscale perforations in the electrospun scaffold will improve transparency, porosity, and gas transport. Additionally, it will provide another additional layer of control on mechanical and degradation properties. The hole diameters were kept consistent at 200 μm with varying hole spacings 50 and 100 μm.

Surface functionalization

The electrospun PLGA scaffolds were functionalized with various ECM protein combinations: (1) 5 µg cm−2 Collagen-IV (Col-IV) (Col IV, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), (2) 0.5 µg cm−2 Laminin-521 (Ln-521, Biolamina, Sundbyberg, Sweden), (3) Col-IV + LN-521 in DPBS by overnight incubation at 4 °C. Plasma treatments were conducted with e-RioTM Atmospheric Pressure Plasma System Model APPR-D300-13 (APJeT, Inc. Santa Fe, New Mexico). It is a glow-discharge plasma reactor powered by radio frequency. Plasma treatment was conducted for 5 min at 300 W plasma power with 2 mm distance between electrode and sample on both sides of the sample. The plasma treatment chamber was supplied with a mixture of helium and oxygen (90:10). The plasma treated samples were immediately submerged in various ECM protein combinations as previously mentioned.

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

The samples were mounted on aluminum SEM stub carbon adhesive followed by sputter-coating (SC7620 Mini Sputter Coater; Quorum Technologies, East Sussex, UK) to achieve a layer of gold and palladium with a thickness of 10 nm prior to examination using the Hitachi TM4000 SEM (Tokyo, Japan).

Light transmittance measurement

To measure light transmittance, the samples were cut into circles with a diameter of 6.5 mm and placed into wells of 96-well plate. The blank control was 100 μm of DPBS and 100 μm of DPBS was also added to each sample. The microplate reader (Synergy HT; BioTek, Winooski, Vermont, US) was used to determine the light transmittance of the constructs under wavelengths in the range between 400 and 750 nm.

Time-of-flight secondary ion mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS)

The samples were put into the ToF-SIMS and set under vacuum overnight prior to the analysis. ToF-SIMS analyses were conducted using a TOF SIMS V (ION TOF, Inc. Chestnut Ridge, NY) instrument equipped with a Bin m+ (n = 1–5, m = 1, 2) liquid metal ion gun, Cs+ sputtering gun and electron flood gun for charge compensation. The analyzed surface area was 500 × 500 μm2 for acquisition of mass spectral images.

Immunostaining for Collagen IV on scaffold surface

To further ensure presence and bio functionality of the ECM proteins on the scaffold surface, immunostaining for ECM proteins were performed. The samples were washed with PBS thrice and blocked for 1 h using a blocking buffer composed of 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 2% goat serum. Then the samples were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C. Later, the samples were washed with PBS and incubated with secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Imaging was done using a fluorescent microscope (EVOS FL Auto 2; ThermoFisher). Antibodies used for this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1.

Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived limbal stem cell (iPSC-LSC) culture and seeding

For this study, iPSCs (iPS-DF19-9-7T, WiCell, Madison, WI) were used. The iPSCs were cultured on a 6 well plate (3506, Corning, Glendale, AZ, USA) coated as per the manufacturer’s instruction with LN-521 using E8 flex media (A2858501, ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Differentiation towards LSC was done using modified protocol from Abdalkader et al.48. In brief, the iPSCs were plated at 1 × 104 cell/cm2 density on LN-521 coated plate with E8 media supplemented with 10 µM Y27632 dihydrochloride (1254, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA). On the second day, the culture media was changed to E8 media only. For next 4 days, induction medium was used which consisted of E6 (A1516401, ThermoFisher) supplemented with Wnt pathway inhibitor (IWR-1 endo) (3532, R&D Systems), TGF-β inhibitor (A83-01) (72024, STEMCELL Technologies, Cambridge, MA, USA), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (3718-FB-025, R&D Systems) at 2.5 μM, 10 μM, 50 ng/mL, respectively. Following plating, cells were maintained in E6 only media for 6 days to obtain differentiated iPSC-LSC prior to seeding them on the scaffolds. The consistent differentiation of iPSC to LSC using the current protocol was confirmed through analysis of various protein expression markers related to pluripotency and LSC. Currently, there is no universally accepted single marker to identify LSC population instead a combination of LSC markers is used for evaluating efficiency30. We also observed that the morphology of the cells changed to polygonal epithelial cell-like characteristic of LSCs around day 10 of the differentiation with loss of expression of pluripotency marker OCT4 (Supplemental Fig. 1). Expression of PAX6, ∆Np63, and ABCG2 was evaluated through immunocytochemistry and quantified to ensure consistent differentiation with minimal batch to batch variation (Supplemental Fig. 2). Prior to seeding iPSC-LSCs on the scaffolds without any perforations, the scaffolds were sterilized by immersing in 70% ethanol for 30 min. After that, the scaffolds were washed with DPBS three times for 5 minutes each time. Then the samples were cut into 1 × 1 cm2 before placing in the wells of a non-treated 24-well plate (10861-558, VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) with sterile stainless-steel washer (In Dia: 6.4 mm, Out Dia: 12 mm placed on top of each sample. iPSC-LSCs were detached from 6-well plates using TrypLE™ Select Enzyme (12563029, ThermoFisher) after 10 days of differentiation and added to each well at a density of 0.1 × 105 cells per scaffold. Wells coated with LN-521, with cells seeded at the same density, were used as the control. The culture was maintained in E6 media.

Cell viability and proliferation assay

Both cell viability and proliferation assays were conducted on days 1,3,5, and 7 post- seeding of iPSC-LSC, as described previously35. In brief, cell viability was assessed using LIVE/DEAD™ Cell Imaging Kits (488/570) (R37601; ThermoFisher) at 1:4 dilution ratio with DPBS following the manufacturer’s recommendations. After a 25-min incubation at 37 °C, imaging was conducted using a fluorescent microscope (EVOS FL Auto 2; ThermoFisher). For measuring cell proliferation rates, alamarBlue™ Cell Viability Reagent (DAL1100; ThermoFisher) was used. iPSC-LSCs were washed once with DPBS prior to incubation with alamarBlue reagent diluted at a ratio of 1:10 v/v in cell culture medium for 3 h at 37 °C in the dark. Following incubation, supernatants were collected from each well and transferred to a 96-well plate (100 µL each well, 10861-666; VWR, Radnor, PA, USA). Fluorescence intensity was measured using a microplate reader (Synergy HT; BioTek, Winooski, Vermont, US) at 540-nm excitation and 590-nm emission wavelengths.

Morphology analysis

To analyze the morphology of iPSC-LSC on scaffolds, we utilized both f-actin filament staining and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). iPSC-LSCs were fixed after 7 days of culture on scaffolds using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and three washes with DPBS before and after. Permeabilization was carried out using 0.1% TritonX-100 for 15 min. Serum blocking was carried out using 2% bovine serum albumin + 2% goat serum for 1 hour. After that, iPSC-LSCs were stained with phalloidin (R37110; ThermoFisher) overnight at a concentration recommended by the manufacturer (2 drops/ml). Prior to imaging using fluorescent microscope, the iPSC-LSCs were washed with DPBS and counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (H3570, ThermoFisher). To prepare the scaffolds with iPSC-LSC for SEM imaging, the samples were first washed with DPBS thrice for 5 min each time followed by fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. DPBS washing step was repeated after fixing. Then, the samples were washed with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (11652, Electron Microscopy Sciences) at pH 7.2 for 10 min, followed by fixation in a solution of 2% Paraformaldehyde/2.5% Glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M Sodium Cacodylate Buffer (15960-01, Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 30 minutes. Wash with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer at pH 7.2 for 10 min was repeated. The samples were dehydrated using gradually increasing concentrations of ethanol washes (35%, 50%, 70%, 80%, and 95%) for 10 min, followed by three 10-min washes in 100% ethanol, and a final 40-min wash in 100% ethanol. Following dehydration, drying was carried out using 50% ethanol and 50% HMDS (Hexamethyldisilazane) (50-243-18, Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 20 min, followed by 100% HMDS for an additional 20 min. The samples were mounted on SEM stubs with carbon adhesive and sputter coated (SC7620 Mini Sputter Coater; Quorum Technologies, East Sussex, UK) prior to examination using the Hitachi TM4000 SEM (Tokyo, Japan).

Immunocytochemistry and fluorescent microscopy

To investigate stemness and commitment towards corneal epithelial lineage, the expression of several proteins was analyzed using immunocytochemistry. The steps including fixing, permeabilizing, and blocking, were carried out as described in the prior sections. Primary antibodies, diluted in blocking buffer, were applied and left to incubate overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the samples were washed thrice with DPBS and incubated with the secondary antibody diluted in 10% blocking buffer (prepared as a 1:10 dilution of the BSA/goat serum blocking solution described above) for 1 h at room temperature. Antibodies used for this study are listed in Supplemental Table 1. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (1:1000 dilution ratio, H3570, ThermoFisher) and imaged with a fluorescent microscope. Immunofluorescence staining was repeated on at least three independent iPSC-LSC batches (biological replicates).

Real-time quantitative polymerase chain (RT-qPCR) reaction

To analyze relative gene expression, RT-qPCR was used. Total RNA was extracted and purified using Total RNA Purification Plus Micro Kit (48500, Norgen Biotek, ON, Canada) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and purity of the RNA was determined using Nanodrop (ND-ONE-W, ThermoFisher). Reverse-transcription was performed using High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (4368814, ThermoFisher) as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The synthesized cDNA was then amplified and analyzed using TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (4331182, ThermoFisher), as listed in Supplemental Table 2 using QuantStudio 3 (A28567, ThermoFisher) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were conducted with at least three biological replicates. Each biological repeat is defined as a unique passage of cells and includes a minimum of three technical replicates, unless otherwise stated. Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean. For imaging-based assays (e.g., ToF-SIMS, ECM immunostaining, Live/Dead, cytoskeletal staining), representative images are shown from ≥3 independent experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using GraphPad Prism version 9.4.1 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) by one or two-way analysis of variance followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison post hoc test, and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and summarized as * = <0.05, ** = <0.01, *** = <0.0001 for the calculated p-values.

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

DelMonte, D. W. & Kim, T. Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. J. Cataract. Refract. Surg. 37, 588–598 (2011).

Osei-Bempong, C., Figueiredo, F. C. & Lako, M. The limbal epithelium of the eye–a review of limbal stem cell biology, disease and treatment. Bioessays 35, 211–219 (2013).

Dua, H. S. & Azuara-Blanco, A. Limbal stem cells of the corneal epithelium. Surv. Ophthalmol. 44, 415–425 (2000).

O’Callaghan, A. R. & Daniels, J. T. Concise review: limbal epithelial stem cell therapy: controversies and challenges. Stem Cells 29, 1923–1932 (2011).

Ghareeb, A. E., Lako, M. & Figueiredo, F. C. Recent advances in stem cell therapy for limbal stem cell deficiency: a Narrative Review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 9, 809–831 (2020).

Kate, A. & Basu, S. A review of the diagnosis and treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. Front. Med. 9, 836009 (2022).

Goldberg, J. S., Fraser, D. J. & Hou, J. H. Prevalence of limbal stem cell deficiency at an academic referral center over a two-year period. Front. Ophthalmol. 4, 1392106 (2024).

Vazirani, J. et al. Surgical management of bilateral limbal stem cell deficiency. Ocul. Surf. 14, 350–364 (2016).

Singh, V., Tiwari, A., Kethiri, A. R. & Sangwan, V. S. Current perspectives of limbal-derived stem cells and its application in ocular surface regeneration and limbal stem cell transplantation. Stem. Cells Transl. Med. 10, 1121–1128 (2021).

Shanbhag, S. et al. Simple limbal epithelial transplantation (SLET): review of indications, surgical technique, mechanism, outcomes, limitations, and impact. Indian. J. Ophthalmol. 67, 1265–1277 (2019).

Protzman, N. M. et al. Placental-derived biomaterials and their application to wound healing: a review. Bioengineering 10, 829 (2023).

Mamede, A. C. et al. Amniotic membrane: from structure and functions to clinical applications. Cell. Tissue Res. 349, 447–458 (2012).

Rama, P. et al. Autologous fibrin-cultured limbal stem cells permanently restore the corneal surface of patients with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Transplantation 72, 1478–1485 (2001).

Marangon, F. et al. Incidence of microbial infection after amniotic membrane transplantation. Cornea 23, 264–269 (2004).

Zhou, Z. et al. Nanofiber-reinforced decellularized amniotic membrane improves limbal stem cell transplantation in a rabbit model of corneal epithelial defect. Acta Biomater. 97, 310–320 (2019).

Connon, C. J. et al. The variation in transparency of amniotic membrane used in ocular surface regeneration. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 94, 1057–1061 (2010).

Hopkinson, A., Mcintosh, R. S., Tighe, P. J., James, D. K. & Dua, H. S. Amniotic membrane for ocular surface reconstruction: Donor variations and the effect of handling on TGF-β content. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 4316–4322 (2006).

Kong, B. & Mi, S. Electrospun scaffolds for corneal tissue engineering: a review. Materials 9, 614 (2016).

Ahearne, M., Fernández-Pérez, J., Masterton, S., Madden, P. W. & Bhattacharjee, P. Designing scaffolds for corneal regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1908996 (2020).

Ortega, I., McKean, R., Ryan, A. J., MacNeil, S. & Claeyssens, F. Characterisation and evaluation of the impact of microfabricated pockets on the performance of limbal epithelial stem cells in biodegradable PLGA membranes for corneal regeneration. Biomater. Sci. 2, 723–734 (2014).

Sefat, F. et al. Production, sterilisation and storage of biodegradable electrospun PLGA membranes for delivery of limbal stem cells to the cornea. Procedia Eng. 59, 101–116 (2013).

Kong, B. et al. Tissue-engineered cornea constructed with compressed collagen and laser-perforated electrospun mat. Sci. Rep. 7, 970–13 (2017).

Ramachandran, C. et al. Proof-of-concept study of electrospun PLGA membrane in the treatment of limbal stem cell deficiency. Bmj. Open. Ophthalmol. 6, e000762 (2021).

Kabosova, A. et al. Compositional differences between infant and adult human corneal basement membranes. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48, 4989–4999 (2007).

Torricelli, A. A. M., Singh, V., Santhiago, M. R. & Wilson, S. E. The corneal epithelial basement membrane: structure, function, and disease. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 54, 6390–6400 (2013).

Hegemann, D., Brunner, H. & Oehr, C. Plasma treatment of polymers for surface and adhesion improvement. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B. 208, 281–286 (2003).

Lotz, O. et al. Reagent-free biomolecule functionalization of atmospheric pressure plasma-activated polymers for biomedical applications: pathways for covalent attachment. Appl. Surf. Sci. 662, 160101 (2024).

He, F., Li, J. & Ye, J. Improvement of cell response of the poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)/calcium phosphate cement composite scaffold with unidirectional pore structure by the surface immobilization of collagen via plasma treatment. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces 103, 209–216 (2013).

Wu, Z., Kong, B., Liu, R., Sun, W. & Mi, S. Engineering of corneal tissue through an aligned PVA/collagen composite nanofibrous electrospun scaffold. Nanomaterials 8, 124 (2018).

Mahmood, N. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived corneal cells: Current status and application. Stem. Cell. Rev. Rep. 18, 2817–2832 (2022).

Ye, L., Swingen, C. & Zhang, J. Induced pluripotent stem cells and their potential for basic and clinical sciences. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 9, 63–72 (2013).

Theerakittayakorn, K. et al. differentiation induction of human stem cells for corneal epithelial regeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21, 7834 (2020).

Blasi, P. Poly (lactic acid)/poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)-based microparticles: an overview. J. Pharm. Investig. 49, 337–346 (2019).

Deshpande, P. et al. Simplifying corneal surface regeneration using a biodegradable synthetic membrane and limbal tissue explants. Biomaterials 34, 5088–5106 (2013).

Mahmood, N., Sefat, E., Roberts, D., Gilger, B. C. & Gluck, J. M. Application of noggin-coated electrospun scaffold in corneal wound healing. Transl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 12, 15 (2023).

Beems, E. M. & Van Best, J. A. Light transmission of the cornea in whole human eyes. Exp. Eye. Res. 50, 393–395 (1990).

Asadian, M. et al. Fabrication and plasma modification of nanofibrous tissue engineering scaffolds. Nanomaterials 10, 119 (2020).

Park, H., Lee, K. Y., Lee, S. J., Park, K. E. & Park, W. H. Plasma-treated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanofibers for tissue engineering. Macromol. Res. 15, 238–243 (2007).

Gattazzo, F., Urciuolo, A. & Bonaldo, P. Extracellular matrix: a dynamic microenvironment for stem cell niche. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1840, 2506–2519 (2014).

Li, S., Sun, H., Chen, L. & Fu, Y. Targeting limbal epithelial stem cells: master conductors of corneal epithelial regeneration from the bench to multilevel theranostics. J. Transl. Med. 22, 794–26 (2024).

Anton-Sales, I., Koivusalo, L., Skottman, H., Laromaine, A. & Roig, A. Limbal stem cells on bacterial nanocellulose carriers for ocular surface regeneration. Small 17, e2003937–n/a (2021).

Polisetti, N. et al. Laminin-511 and -521-based matrices for efficient ex vivo-expansion of human limbal epithelial progenitor cells. Sci. Rep. 7, 5152–15 (2017).

Huang, H., Ye, K. & Jin, S. Cell seeding strategy influences metabolism and differentiation potency of human induced pluripotent stem cells into pancreatic progenitors. Biotechnol. J. 20, e70022 (2025).

Teslaa, T. & Teitell, M. A. Pluripotent stem cell energy metabolism: an update. Embo. J. 34, 138–153 (2015).

Schlötzer-Schrehardt, U. et al. Characterization of extracellular matrix components in the limbal epithelial stem cell compartment. Exp. Eye. Res. 85, 845–860 (2007).

Li, D. et al. Partial enrichment of a population of human limbal epithelial cells with putative stem cell properties based on collagen type IV adhesiveness. Exp. Eye. Res. 80, 581–590 (2005).

Vattulainen, M. et al. Modulation of Wnt/BMP pathways during corneal differentiation of hPSC maintains ABCG2-positive LSC population that demonstrates increased regenerative potential. Stem. Cell. Res. Ther. 10, 236 (2019).

Abdalkader, R. & Kamei, K. An efficient simplified method for the generation of corneal epithelial cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Hum. Cell. 35, 1016–1029 (2022).

Acknowledgements

Schematics and TOC Graphic were created with BioRender. This work was performed in part at the Analytical Instrumentation Facility (AIF) at North Carolina State University, which is supported by the State of North Carolina and the National Science Foundation (award number ECCS-2025064). The AIF is a member of the North Carolina Research Triangle Nanotechnology Network (RTNN), a site in the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI). This work made use of the NUFAB facility of Northwestern University’s NUANCE Center, which has received support from the SHyNE Resource (NSF ECCS-2025633), the IIN, and Northwestern’s MRSEC program (NSF DMR-1720139). The research was partially supported by the Wilson College Research Opportunity Seed Funding program (JMG), the NCSU Laboratory Research Equipment Program (JMG), the Wilson College of Textiles (JMG), the Department of Textile Engineering, Chemistry and Science (NM, JMG), the North Carolina Textile Foundation—Wilson College Fellowship (NM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M.: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, analysis, data curation, writing original draft; D.Z.: investigation and methodology; S.G.: investigation; M.R.E.: investigation and methodology; U.M.J.: investigation, methodology, and analysis; A.E.: supervision, writing review and editing; B.C.G.: supervision, writing review and editing; J.M.G.: conceptualization, supervision, writing review and editing, funding acquisition and resources

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mahmood, N., Zha, D., Gullion, S. et al. Surface modified electrospun scaffold supports iPSC-derived limbal stem cell function. npj Biomed. Innov. 3, 14 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-026-00066-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44385-026-00066-w