Abstract

While humans and AI-powered machines are expected to complement each other—for example, leveraging human creativity alongside AI’s computational power to achieve synergy (“1 + 1 > 2”)—the extent to which human–machine teaming (HMT) realizes this potential remains uncertain. We investigated this issue through reliability analysis of data from 52 empirical studies in clinical settings. Results show that medical AI can augment clinician performance, yet HMT rarely achieves full complementarity. Two factors matter: (1) teaming mode, with the simultaneous mode (clinicians review diagnostic cases and AI outputs concurrently) yielding greater benefits than the sequential mode (clinicians make initial judgments before reviewing AI outputs); and (2) clinician expertise, with juniors benefiting more than seniors. We also addressed two practical questions for medical AI deployment: how to predict or explain HMT reliability, and how to achieve clinically significant improvements. These findings advance understanding of human–AI collaboration in safety-critical domains.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) systems are transforming professional domains, ranging from medical diagnosis and surgery to driving and piloting1,2. These AI-powered machines sometimes surpass human capabilities in computational and analytical efficiency, accuracy, consistency, and scalability. We focus on their role in healthcare, where AI is poised to address critical challenges, such as clinician errors—a major contributor to medical accidents and patient harm3. Powerful AI machines like predictive analytics and surgical robots are expected to reduce clinician errors and enhance patient safety, thereby revolutionizing healthcare delivery worldwide4,5. In fact, clinicians have utilized computer-based clinical decision support systems (CDSS) since the 1970s. Recent technological breakthroughs in machine learning, deep learning, and multimodal large language models6,7,8 have expanded these machines’ capacity to process diverse medical data, including images, text, and phenotypic information.

Despite these promising developments, significant debate surrounds the integration of AI into clinical practice. One pathway involves using AI to “automate” certain human tasks and substitute human professionals in these tasks. Proponents, including researchers and AI companies, argue that AI outperforms human doctors in specific areas such as image-based diagnostics9,10, suggesting that automating these tasks could reduce patient harm from a utilitarian perspective11. However, this radical pathway faces economic, regulatory, ethical, and legal hurdles12,13. For instance, removing humans from the decision-making loop complicates liability issues when AI systems err. Clinicians may resist such changes due to concerns about job displacement, while healthcare organizations might hesitate to fully trust AI-driven clinical practice14. Another pathway is to “augment” human professionals by keeping them in the loop. This mode, usually referred to as “human-machine augmentation”, “human-machine collaboration”, “human-machine partnership”, “human-in-the-loop”, “human-machine hybrid”, “human-machine symbiosis”, or “human-machine teaming” (HMT), involves clinicians using machines to support decision-making and other tasks. Clinicians emphasize that machines should act as partners and that the joint human-machine system must remain fundamentally clinician-directed or human-centered15,16,17.

HMT is expected to achieve human-machine complementarity. Complementarity, sometimes used interchangeably with synergy and symbiosis, refers to that “the quality of being different but useful when combined”18 or “the quality of a relationship between two people, objects, or situations such that the qualities of one supplement or enhance the different qualities of the others”19. The distinct nature of humans and machines gives HMT its potential for complementarity20,21,22—for example, by combining human creativity and intuition with machine computational power, thereby overcoming their respective limitations and achieving a “1 + 1 > 2” effect, where the joint team produces outcomes greater than the sum of its individual parts. For further conceptual underpinnings of complementarity and its synonyms in HMT across different domains, please refer to works22,23,24,25,26. However, their distinct nature may also imply potential incompatibilities27,28. In particular, the opaque and data-driven features of AI make it difficult for humans to understand and explain its outputs. Empirical research from human factors, human-AI interaction, and psychology highlights deeper issues arising from the interaction process. One notable issue is that AI systems may induce significant clinician biases (e.g., over-reliance, misuse, or even inheriting machine biases) in real or simulated clinical diagnostic tasks29,30,31. AI machines, as well as clinicians, have their own biases and far from perfect32, and both inexperienced and experienced clinicians are prone to being misled by biased and imperfect machines29,33. As a result, findings regarding HMT’s impact in healthcare are mixed and non-conclusive: while many individual and review studies34,35,36,37 reported encouraging results, others38,39 did not. In the long term, over-reliance on or continuous use of machines may have negative effects on clinicians, such as deskilling or dethrilling12,40, which may also produce uncertain impacts on patient safety and healthcare quality. Therefore, whether HMT can achieve satisfactory synergy or perfect complementarity remains uncertain, despite its growing adoption in healthcare. Given that certain medical AI devices have been approved in USA, Europe, China, among others35, it is important to better understand HMT in clinical settings. For this reason, our current work aims to advance understanding of human-AI collaboration and provide insights into AI implementation in healthcare and other safety-critical domains.

We focus on a special type of HMT: machines act as a “co-pilot” or second clinician41. They provide independent suggestions that humans can incorporate into their suggestions to derive a final judgment or decision. This type of HMT structurally resembles a system with two parallel units. According to traditional reliability analysis, the joint system fails only when both units fail. Probabilistically, the system’s reliability (Rsystem) is one minus the product of the unreliabilities of its two parallel units (see Fig. 1A). In other words, the system’s error rate is the product of its two units’ error rates. Reliability (i.e., the number of successes divided by the number of patient cases or tasks) is conceptually identical to accuracy, a common metric for diagnostic performance in healthcare (other metrics include sensitivity, specificity, etc.). Compared with the parallel system illustrated in Fig. 1A, the human–machine joint system may follow a similar reliability logic but can also violate the independence assumption and deviate for cognitive, social, or structural reasons. We next discuss these potential deviations and propose four HMT scenarios (see Fig. 1B): Utopia, Ideal, Complementary, and Conflict.

In the Utopia scenario (1 + 1 > 2 or H + M > 2), HMT achieves a reliability higher than the calculated system reliability through the equation in Fig. 1A. When the two units in the system work in parallel and independently, or when they do not influence each other, the Utopia scenario is, of course, impossible in traditional reliability terms. However, if humans and machines possess self-learning and co-learning abilities, along with perfect human-machine co-evolution, the Utopia scenario could be realized in the long term. More specifically, humans and machines in the Utopia scenario continuously learn and improve through mutual feedback and outputs during their interaction42. In this scenario, humans and machines enhance each other through a reciprocal learning process.

In the Ideal scenario (1 + 1 = 2 or H + M = 2), humans and machines can work together and fully leverage their complementary strengths and weaknesses. Notably, this Ideal scenario does not imply that HMT will never fail. Instead, it means that HMT fails only when both agents fail (see Fig. 1A). Humans make the final decisions and retain ultimate authority. Thus, the Ideal scenario requires a kind of “perfect” human: when clinicians make correct judgments, they are confident in their own judgments, even if their machine partners provide conflicting or misleading judgments. Conversely, when they make incorrect judgments, they recognize their errors when machine partners offer inconsistent judgments and can correct their previous judgments. In other words, clinicians in the Ideal scenario are able to evaluate machine outputs and are not misled by incorrect machine outputs. Of note, the assumption of “perfect” humans does not always hold, as demonstrated in the cognitive psychology and human-computer interaction literatures27,28,29,43. Machines such as medical AI are often used by imperfect human partners44.

In the Complementary scenario (1 < 1 + 1 < 2 or H < H + M < 2), machines assist humans and HMT outperforms humans alone. There is no widely accepted metric for complementarity in the HMT literature22. The human-human team literature45 distinguishes weak complementarity (i.e., the team outperforms its average member, also called “weak synergy”) from strong complementarity (i.e.,., the team outperforms its best member, also called “strong synergy”). Even if HMT does not surpass machines alone, outperforming humans still represents progress over the status quo and demonstrates complementarity to some degree46. Also, for a stricter criterion, Steyvers et al.47 proposed that HMT should outperform the best performer between machines and humans, expressed mathematically as Max (H, M) < H + M < 2. The Ideal scenario represents a special case of complementarity—full complementarity or perfect complementarity.

In the Conflict scenario (1 + 1 < 1 or H + M < H), there exist human-machine conflicts and antagonism in judgments and control. A more severe version occurs when HMT underperforms both humans and machines individually, that is, H + M < Min (H, M). Such conflicts often stem from, or are indicated by, inconsistent judgments between humans and machines48. In clinical settings, it is not rare to find that machines’ judgments frequently conflict with humans’ initial judgments14. Sometimes, this may also be because human professionals highly value unaided performance and perceive machines as challengers, competitors, or adversaries49, leading to explicit conflicts. Notably, that HMT underperforms both is not only due to human-machine conflicts. For instance, Wies et al.50 reported that 3.9% of cases in their dataset involving explainable AI are that both the clinician and AI diagnosis are correct but the clinician subsequently switches to an incorrect diagnosis, which they explained that “might be caused by unrealistic explanations” from AI. Particularly, improper HMT design can lead to unexpected conflicts and struggles. In some cases, when machines are given human-level or independent decision-making or control authority, their miscommunications can result in extreme conflicts. Although rare, such cases have led to tragedies in history. For example, two Boeing 737 MAX 8 accidents in October 2018 and March 2019 were caused by control conflicts between the pilots and the automated system known as the Maneuvering Characteristic Augmentation System51. These human-machine conflicts in the two accidents resulted in the tragic loss of 346 human lives. While severe conflicts of this nature may not yet occur in current clinical settings, they remain a possibility in other safety-critical domains.

In addition to the inherent reliability of humans and machines, various other human, machine, and teaming factors (referred to as “moderators” in statistical terms) may influence HMT effectiveness52,53. We focus on two key factors: teaming mode and human expertise. Teaming mode pertains to how humans and machines should work together. Effectively integrating medical AI into existing workflows is highly complex for healthcare organizations due to the significant heterogeneity of these workflows. However, a basic question to consider is whether human professionals should review machine outputs after making their own independent judgments (i.e., the sequential mode) or access patient cases and machine outputs simultaneously (i.e., the concurrent mode)54. From a cognitive perspective, this minor difference may lead to distinct clinician errors and involve different ethical and legal considerations. The sequential mode is more susceptible to confirmation bias and anchoring bias55, potentially preventing clinicians from accepting more correct outputs from opaque machines56. However, it requires humans to think independently before incorporating AI outputs, which is expected to reduce overreliance57, but of course, can come at the cost of efficiency (e.g., more time needed). It is currently implemented and legally required in some clinical practices14 and preferred in certain works55,58, at least in the present and near future. But some studies directly or indirectly comparing the two modes59,60 have favored the concurrent mode and reported that this mode not only saves time for human professionals but has also been shown to improve accuracy. Thus, more research is needed to further explore the impact of teaming mode.

Not all humans benefit equally from AI in HMT25,26. Their expertise, pertains to who should be, and will be, augmented by machines25. As a multidimensional concept, expertise can refer to different characteristics, including years of clinical experience, trainee status (e.g., interns vs. consultants), professional rank (e.g., residents vs. attending physicians), task-specific expertise (e.g., specialization in the relevant task), and prior experience with AI tools. Theoretically, senior professionals may gain more benefits than juniors, as they are more adept at evaluating AI outputs and integrating them into their own work. Vaccaro et al.21 provided evidence supporting this notion, showing that when humans outperform machines, their collaboration leads to performance gains, whereas when humans underperform machines, their teaming results in performance losses. In contrast, certain studies35,61,62,63 in healthcare suggest the opposite: senior professionals often gain less from collaboration with AI teammates compared to their junior counterparts. Tschandl et al.36 found that the net improvement from AI usage has a negative relationship with clinicians’ years of experience in skin cancer recognition tasks. This intriguing finding may partly stem from the challenge of further improving the already high diagnostic accuracy of senior clinicians. However, it also raises a deeper cognitive question: it might indicate that juniors appear more likely to exhibit a tendency known as “algorithmic appreciation”, while seniors are more prone to “algorithmic aversion”64. Notably, other empirical studies have reported conflicting findings. For example, years of expertise were identified as a poor predictor of AI’s assistive impact in chest X-ray diagnostic tasks65 and knee osteoarthritis diagnostic tasks66. Therefore, the heterogeneous effects of AI augmentation across expertise levels remain unclear, highlighting the need for further investigations.

Here, we aim to examine HMT through reliability analysis based on current empirical studies that provide human reliability, machine reliability, and their teaming reliability. Several reviews have discussed medical AI’s impact on clinician performance. They used narrative reviews38,39,67 and meta-analysis35 to answer certain key questions, such as whether HMT outperforms its individual components and whether medical AI can help clinicians. However, we recognize that reliability analysis provides more nuanced insights into various HMT scenarios in clinical settings. More importantly, reliability analysis, unlike standard meta-analysis methods used in previous reviews, can address questions with strong practical relevance, such as whether HMT reliability can be predicted or explained. More specifically, we addressed four key research questions (RQs). It is theoretically essential to determine whether HMT can improve reliability compared to individual agents (RQ1) and whether humans and machines can achieve complementarity (RQ2). Our investigation of RQ1 and RQ2 will largely extend existing narrative reviews and meta-analysis35,38,39,67. Practically, while HMT reliability in healthcare is context-specific, it is critical for organizations and regulatory bodies to predict HMT reliability before implementing medical AI (RQ3) and to understand how to achieve clinically significant improvements through its deployment (RQ4). To the best of our knowledge, these two practical questions have not yet been explored in the literature.

-

RQ1: Does HMT outperform humans? We want to measure the added value of HMT over humans in terms of reliability analysis. If HMT cannot outperform human professionals, it would indicate the presence of human-machine conflicts in their judgments. Previous studies34,68 have reported mixed findings on this question. One potential explanation is that the added value of HMT might be constrained by factors such as teaming modes (sequential vs. simultaneous) and human expertise (non-expert vs. expert, junior vs. senior). Therefore, we will also evaluate the added value of HMT across different teaming modes and varying levels of clinician expertise.

-

RQ2: Can HMT achieve perfect complementarity? Even if HMT statistically outperforms human professionals, it does not necessarily achieve ideal or sufficient complementarity. The current literature provides limited insights into this issue. Ideal HMT only fails when both agents fail. We will compare observed HMT reliability with calculated ideal HMT reliability and introduce a metric called the “complementarity ratio” (observed HMT reliability divided by ideal HMT reliability). We will then explore the factors influencing this ratio.

-

RQ3: How can we explain or predict HMT? Can we develop empirical models to explain or predict HMT reliability? Deploying AI to support clinicians is not only resource-intensive but also raises significant ethical and legal challenges. For example, HMT could lead to clinicians being unfairly held accountable for errors made by medical AI69. Healthcare organizations seeking to integrate AI tools into clinical workflows must carefully weigh potential benefits against risks. Here, we aim to explain or predict HMT reliability for their informed decision-making.

-

RQ4: How to achieve an improvement of clinical significance from HMT? Again, deploying medical AI is resource-intensive, disrupts established workflows, and requires significant maintenance costs. Healthcare organizations are often uncertain whether AI integration will lead to clinically meaningful improvements70. Even if HMT achieves statistically significant reliability gains, these gains may not translate into practical benefits67. Organizations often have specific criteria for meaningful improvements; for example, certain clinical settings may require a 5% or 10% increase in accuracy71. We will investigate the level of machine reliability needed to achieve such accuracy improvements.

Results

We extracted eligible journal articles (N = 52; see “Methods”) in clinical settings to answer the four RQs. These journal articles provided all reliability data for humans, machines, and their teaming. We coded these papers in terms of teaming mode, clinician expertise, AI type, and other study characteristics (see Table 1). Each article might contain a single experimental condition or multiple conditions and thus it may contribute a single data point or multiple data points at the condition level. Here, a “condition” refers to the combination of a teaming mode (sequential vs. simultaneous vs. unclear) and an expertise level (junior vs. senior vs. unclear). We finally had 54 study-level and 87 condition-level data points for further reliability analysis (see Table 2).

In our included conditions (n = 87), none of them reported the Utopia or Ideal scenarios (see Table 3). Among them, 83 conditions fell into the Complementary scenario, where HMT reliability exceeded human reliability. Within this scenario, fewer than 50% of the conditions (n = 38) showed evidence of strong complementarity (i.e., observed HMT reliability > both human and machine reliability). Four conditions offered evidence of the Conflict scenario, indicating that human reliability decreased with AI assistance. HMT reliability was lower than both human and machine reliability in two conditions.

RQ1: Does HMT outperform humans?

Using the lme4 package in R72 (version: v1.1-35.5), we applied a weighted linear “intercept-only” mixed-effects model based on conditional-level data: lmer (reliability difference ~1 + (1 | ArticleID) + (1 | Expertise) + (1 | Teaming mode)). Here, “reliability difference” represents observed HMT reliability minus human reliability, with a positive intercept indicating that HMT reliability, on average, exceeds human reliability. We included ArticleID as a random effect to account for dependencies within articles and added expertise level and teaming mode to capture variability in clinician expertise and teaming impacts (the impacts of clinician expertise and teaming mode are examined later). Condition weights, calculated by multiplying clinician participants by diagnostic cases/tasks (see Table 2), were included in the model. The model showed that its coefficient for reliability difference was positive and deviated from zero (β = 0.071, SE = 0.018, t = 3.973, p = 0.024). Three robustness checks were performed. First, a similar analysis on study-level data (with ArticleID included as a random effect) yielded a comparable result (β = 0.076, SE = 0.007, t = 10.180, p < 0.001). Second, a weighted paired-t test on reliability difference (which did not, or cannot, account for random effects) confirmed the result (condition-level data: △M = 0.072, t = 11.405, p < 0.001). Third, excluding condition-level data labeled as “unclear” for teaming mode or expertise (n = 63) yielded a similar result (β = 0.080, SE = 0.011, t = 7.117, p < 0.001; both teaming mode and expertise were removed sequentially from the model due to convergence failures). Thus, regarding RQ1, observed HMT reliability, on average, was greater than human reliability (see Fig. 2A). In addition, excluding condition-level data labeled as “unclear” for teaming mode or expertise did not affect our findings in other statistical analyses, and these results are reported in Supplementary Table 5.

Observed HMT reliability was higher than human reliability (A), but not higher than machine reliability (B) or the reliability of the better of humans and machines (C), and was lower than ideal HMT reliability (D). Condition-level data are used. Weights = the number of clinicians * the number of diagnostic cases.

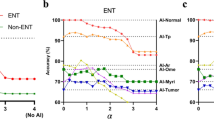

Next, a weighted linear mixed-effects model was used to investigate the impacts of expertise level and teaming mode on reliability difference between observed HMT reliability and human reliability. Conditions labeled “unclear” for expertise level or teaming mode were excluded. The model included clinicians’ expertise level (senior vs. junior), teaming mode (simultaneous vs. sequential) and their interaction as fixed effects, with ArticleID as a random effect: lmer (reliability difference ~ Teaming mode * Expertise + (1 | ArticleID)). Clinician expertise significantly influenced the reliability difference (β = 0.047, SE = 0.010, t = 4.621, p < 0.001), with juniors showing a greater reliability improvement than seniors (see Table 4). Teaming mode significantly affected the reliability difference (β = 0.044, SE = 0.021, t = 2.099, p = 0.040). Clinicians working with AI through the simultaneous versus sequential modes had a greater reliability improvement (see Table 4). The interaction effect was not significant (β = 0.011, SE = 0.023, t = 0.472, p = 0.639). As shown in Table 4, HMT in the sequential mode showed minimal improvements for senior clinicians.

Similarly, we compared observed HMT reliability with the best performer between humans and AI alone through the same model. Due to singular fits, we simplified the model for condition-level data (with expertise and ArticleID as random effects), as described earlier, which revealed no significant difference in reliability between HMT and the best of humans or AI alone (β = –0.018, SE = 0.013, t = –1.422, p = 0.243); see Fig. 2C. However, while using study-level data, HMT had a lower reliability level than the best performer (β = –0.019, SE = 0.007, t = –2.872, p = 0.006). Thus, caution should be exercised when determining the reliability difference between HMT and the best of its two agents.

For exploratory purposes, we compared observed HMT reliability with machine reliability using the same weighted linear “intercept-only” mixed-effects model, applied to both condition-level data (with the three random effects) and paper-level data (with ArticleID as the random effect). During this analysis, a singular fit issue was encountered with conditional-level data. We addressed this issue by stepwise removal of random effects with the least variance73, which yielded a model that excluded teaming mode as a random effect. We found non-significant differences between observed HMT reliability and machine reliability (condition-level data: β = –0.007, SE = 0.015, t = –0.437, p = 0.686; study-level data: β = –0.008, SE = 0.009, t = –0.945, p = 0.349); see Fig. 2B. Thus, HMT was not better than machines alone.

RQ2: Can HMT achieve complementarity?

The quantitative metric for complementarity is not yet well-established. From a reliability analysis perspective (see Fig. 1), we proposed two metrics and conducted two tests. First, we compared observed HMT reliability with ideal HMT reliability. Intuitively, if observed reliability was not lower than ideal one, it would indicate full complementarity. Using a weighted linear mixed-effects model similar to that for RQ1, with their reliability difference as the outcome variable. Due to convergence failures, random intercepts were stepwise removed from the model based on condition-level data, starting with the terms contributing the least variance74, finally yielding a simplified model with ArticleID and expertise as random effects. Observed HMT reliability was lower than ideal HMT reliability (condition-level data: β = –0.123, SE = 0.015, t = –8.465, p = 0.003; study-level data: β = –0.125, SE = 0.009, t = –14.210, p < 0.001). Thus, HMT did not achieve full complementarity in terms of reliability (see Fig. 2D).

Second, we proposed a continuous, quantitative metric called the “complementarity ratio”: observed HMT reliability divided by ideal HMT reliability. Its greater value means greater complementarity and its value of 1 means full complementarity. We explored its linear relationship with reliability gap between machines and humans (i.e., MR – HR). We used a weighted linear mixed-effects model with three random effects and found a significant negative relationship between complementarity ratio and reliability gap (β = –0.291, SE = 0.055, t = –5.252, p < 0.001). Figure 3A shows the model with fixed effect estimates. As reliability gap between machines and humans increases, their complementarity ratio decreases.

A describes the significant negative relation between complementarity ratio (observed/ideal HMT reliability) and reliability gap (machine reliability – human reliability). B describes the significant positive relation between relative improvement (observed HMT reliability/human reliability – 1) and reliability gap. These models are exploratory rather than explanatory.

RQ3: How to explain or predict HMT?

To explain or predict HMT, we had two attempts. We first built a weighted linear mixed-effects model, treating human reliability, machine reliability, and their interaction as fixed effects to capture their direct influences on teaming reliability. Expertise level, teaming mode, and ArticleID were included as random intercepts. However, this model failed the multi-collinearity check. Using the variance inflation factor (VIF) to assess collinearity75, we found high collinearity among machine reliability (VIF = 14.78), human reliability (VIF = 67.69), and the interaction term (VIF = 116.59). This linear regression model was problematic and thus discarded.

Second, we explored an alternative approach to explain observed HMT. Given that machine and human reliability are known, their ideal teaming reliability can be estimated in advance through the equation in Fig. 1. This allows for using ideal HMT reliability to explain or predict observed HMT reliability. We tested several models, including linear and non-linear versions, with and without teaming mode and expertise. Visual inspection (Fig. 2D) suggested that a non-linear model was more appropriate. Using the criterion of Akaike Information Criterion (AIC)76 to select the best model, we identified a weighted non-linear mixed-effects model with ArticleID as a random effect, which had the lowest AIC score (see Supplementary Table 4 for all information). Figure 2D shows the model’s fixed effect estimates. Notably, this quantitative model is exploratory rather than explanatory. Future research should formulate directional hypotheses to test the empirical relationships it implies.

RQ4: How to achieve an improvement of clinical significance from HMT?

Of meaningful clinical significance, some clinical settings may require medical AI to deliver a 5% or 10% improvement over human performance71. We operationalized “relative improvement” as observed HMT reliability divided by human reliability minus one (i.e., observed HMT reliability/HR – 1) and examined it as a function of reliability gap between machines and humans. Machine reliability and human reliability must be known in advance; otherwise, it is hard to quantitatively estimate the added value of medical AI in practice. We first used a weighted linear mixed-effects model with three random effects, but it resulted in a singular fit. Expertise and mode were removed from random effects since values of their variance were zero. We found a positive relationship between relative improvement and reliability gap between machines and humans (β = 1.035, SE = 0.077, t = 13.360, p < 0.001). Figure 3B displays the model with the fixed effect estimates. Among the conditions, 66.7% (58 of 87), 37.9% (33 of 87), and 16.1% (14 of 87) achieved a 5%, 10%, and 20% relative improvement, respectively. Notably, these three improvement thresholds were not derived from clinical guidelines or regulatory requirements. What counts as a “clinically meaningful” improvement in medical AI applications depends on the significance of the tasks involved and the risk preferences of organizational stakeholders; thus, there is no consensus on a universal threshold.

Discussion

Despite the significant potential of AI-powered machines to augment and team with human professionals and their growing prevalence, their teaming reliability in safety-critical sectors remains largely unexplored. Here we examined HMT in healthcare using reliability analysis, representing, to the best of our knowledge, the first effort of its kind. We offer new perspectives on the key questions, including whether machines benefit human professionals such as clinicians (RQ1) and whether these distinct cognitive agents (humans and machines) can form a complementary partnership (RQ2). We also investigated the moderating effects of their teaming modes and human expertise on their teaming reliability. In particular, we explored two critical practical questions: “How to explain or predict HMT?” (RQ3) and “How to achieve an improvement of clinical significance from HMT?” (RQ4). Our findings are expected to provide insights for developing and deploying effective HMT in safety-critical sectors.

Our central finding challenges the prevailing narrative around complementary-performance claims for HMT in academia and public discourse77. In our reliability analysis, HMT did not achieve the Utopian or Ideal scenarios described in Fig. 1. It neither outperformed medical AI alone (see Fig. 2B) nor surpassed the best of clinicians or medical AI alone (see Fig. 2C). A recent meta-analysis on HMT, based on effect size metrics21, across both healthcare and non-healthcare domains reported a similar finding. Several factors may be linked to this outcome. At a surface level, clinicians and medical AI might not effectively complement each other, as they tend to fail in similar cases and cannot adequately cover each other’s mistakes. Because medical AI is trained on human data and can inherit human biases, these two agents might fail in the same cases (that is, they may have common cause failures, in the language of reliability analysis). At a deeper level, previous research suggested that clinicians may struggle to accurately assess both their own and AI’s capabilities and judgments in clinical scenarios characterized by high uncertainties and complexities28 or face other challenges in their collaboration28,78. In addition, in four out of 87 conditions, we observed potential human-machine conflicts, where the team’s performance was lower than that of humans. Given that even human-human teams often fail to achieve strong complementarity45, we conclude that we should remain cautious about the popular belief that humans and machines can seamlessly integrate and fully exploit the advantages of hybrid intelligence, particularly, in safety-critical sectors.

However, our analysis still revealed that HMT, on average, outperformed clinicians alone. This contrasts with certain reviews38,39, which, based on narrative analysis, found no clear evidence of machines effectively supporting clinicians in healthcare. But our finding is indirectly supported by a recent study by Han et al.67, which reported significant improvements from AI assistance in 46 out of 58 studies, with the remaining 10 showing non-significant improvements. Another recent review21 found that human-AI collaboration outperformed humans alone in tasks involving decision making and content generation in broader settings.

Compared to previous reviews in healthcare, our study contributes to the literature by identifying two key moderators that influence HMT and offers a nuanced understanding: teaming mode (simultaneous vs. sequential) and human expertise (juniors vs. seniors). Both moderators highlight intriguing challenges and even ironies in designing and optimizing HMT within and beyond, as discussed below.

The key difference between the simultaneous and sequential modes lies in the timing of machine outputs provided to humans. The sequential mode is usually favored55,58, as it would promote human engagement and thus reduce over-reliance and de-skilling. This mode has been implemented in clinical practice and often legally required14. Unexpectedly, our reliability analysis, based on a body of empirical studies, more supports the simultaneous mode. Certain key aspects, such as clinician burden, human factors (e.g., whether clinicians employ metacognition to evaluate and integrate AI outputs), and workflow integration79,80, can provide theoretical scaffolding for our observation of the teaming mode. For instance, is the relative advantage of the simultaneous mode due to clinicians simply following medical AI, or does it reflect clinicians’ deliberate integration of AI outputs? The former represents a kind of “unengaged” augmentation80, which will be especially harmful when AI provides incorrect outputs, whereas the latter reflects “engaged” augmentation. Further investigation is needed to clarify these theoretical conundrums and find optimal teaming processes that integrate humans and machines.

Junior clinicians, compared to seniors, experienced significant reliability improvements when working with medical AI. In particular, senior clinicians in the sequential mode showed negligible improvements. This difference would be surprising from a cognitive perspective: as senior clinicians are assumed to have greater meta-knowledge and meta-cognition for assessing AI outputs and identifying and compensating for mistakes21,25, they are expected to benefit more from AI than juniors. In fact, this surprising finding consolidates previous experimental studies that have reported that senior workers, compared to junior workers, benefit less from working with machines in healthcare61,62,63. One superficial hypothesis is that senior clinicians already possess a high level of decision reliability, making further improvements difficult. Other, more in-depth psychological hypotheses also deserve attention. For instance, senior clinicians, due to years of training and practice, may have high confidence in their judgments55 and greater resistance to machines, even when their judgments are inferior to the machine’s outputs. In contrast, junior clinicians, or non-experts, are generally more willing to value machine outputs. However, the genuine challenge is that it remains unclear whether they can truly assess both their own and the machine’s outputs and select the best one, or whether they simply follow the machine as a cognitive heuristic54 (e.g., they know that machine judgments are based on a large collection of expert annotations81 or believe that machine judgments reflect the wisdom of crowd experts). These speculations underscore the importance of better understanding the underlying mechanisms of HMT and how it can truly benefit clinicians.

In addition, while machines with a greater reliability advantage over humans lead to greater relative improvement for humans (see Fig. 3B), this advantage is also more likely to reduce complementarity potential (Fig. 3A). These two results are not contradictory; rather, they suggest that a decreasing complementarity ratio reflects the diminishing marginal effect of increasing machine reliability. This is an intriguing point that has been largely overlooked in the HMT literature: misaligned capabilities, particularly in terms of reliability, may hinder human-machine complementarity. Vaccaro et al.21 observed a related phenomenon: when AI outperformed humans, the human-AI joint system experienced greater performance losses relative to AI alone. This suggests that clinicians may struggle to fully exploit the advantages of superior machines and appropriately utilize their capabilities.

Taken together, the above findings highlight the complexity of HMT and identify three key factors that influence teaming reliability and complementarity beyond the individual reliability of humans and machines: teaming mode, human expertise, and reliability gap. Theories are the backbone of any research field. Previous work theorizing HMT in healthcare and beyond has largely focused on concepts such as trust82, collective intelligence83, and mind and social perceptions of machines84. These conceptual studies have provided valuable insights into HMT. However, they often overlook the safety and reliability of HMT, which should be the top priority in safety-critical systems like healthcare. We recommend focusing on measurable concepts, such as reliability, and developing theories based on explicit factors like teaming mode and the reliability gap between humans and machines. In addition, we call for more theoretical work to clarify how AI augments clinicians in practice and to identify the factors that limit its impact.

The above findings have practical implications. As discussed earlier, we provide empirical insights to calibrate the current hype surrounding human-AI complementarity. Specifically, we develop data-driven empirical model to assess HMT reliability and pre-determine the required machine reliability to achieve expected clinical improvement, which offering valuable guidance for informed AI implementation decisions. Our results shed light on the complexity of human-AI interactions in teaming relationships and clinical performance. For instance, senior clinicians, on average, do not derive significant benefits from medical AI in the sequential teaming mode. However, this does not imply that senior clinicians are less capable of teaming with AI or cannot be responsibly and reliably augmented by it. Instead, it raises critical practical concerns. For example, given that medical AI’s use is often legitimized based on its anticipated benefits, how should healthcare organizations grant autonomy and discretion to senior clinicians if teaming with AI cannot bring benefits to seniors? In addition, we found that the simultaneous teaming mode is more likely to “augment” clinicians in terms of reliability compared to the sequential mode, whereas the sequential mode has been implemented and legally mandated14. Evidence-based practice plays a crucial role in healthcare decision-making. Then, should healthcare organizations or authorities support the simultaneous mode over the sequential mode? All of these exemplified questions hold strong ethical and legal implications85.

We acknowledge certain limitations in our work and discuss future opportunities. First, although we reported that HMT outperformed humans alone based on the included studies, its generalizability should be interpreted with caution for several reasons. The impact of HMT may vary across different specialties. However, the currently collected data do not allow us to perform subgroup analyses for specific specialties. Most of the included studies focused on AI applications in image-rich specialties. Another concern relates to the potential risk of publication bias in the included studies or others assessing medical AI. While some reviews (e.g., ref. 35) claimed they did not detect publication bias, others (e.g., refs. 41,67) expressed concerns about it. For example, failures or negative outcomes of medical AI are often not formally reported86, and a recent work87 revealed the high prevalence of unsubstantiated superiority claims in publications from a medical imaging AI conference. Such publication bias poses a significant threat to any review-based work aiming to extract the overall impacts and effectiveness of medical AI. This bias, of course, did not affect our central finding that HMT failed to achieve perfect complementarity, but would imply, if its prevalence is confirmed (see ref. 87), that the reliability of the observed average improvements in HMT (relative to human reliability; see Table 4) may be overestimated and that optimism about HMT should be tempered with realism. In addition, not all included studies were methodologically robust. For instance, some studies involved an insufficient number of clinician participants (see Table 1). Certain studies (e.g., ref. 88) evaluated humans with and without AI assistance simultaneously (using AI assistance in a within-subject design) but did not adopt a randomized design, likely due to implementation challenges. Also, most studies were not conducted in real-world clinical environments. In healthcare, clinician factors (e.g., time pressure, cognitive workload), institutional factors (e.g., workflows, organizational climates), and economic constraints differ substantially from simulated and controlled conditions, raising concerns about the external validity of current HMT findings89. To sum up, these methodological issues warrant further scrutiny and challenge the reproducibility and external validity of some of the involved studies, as well as others in healthcare.

Second, we focused on a specific type of HMT, where machines act as a “co-pilot” and serve as a second advisor41. This choice was motivated by dozens of studies on this type of HMT and its integration into current clinical workflows14. We did not examine other types of HMT, such as those where humans and machines perform sub-tasks that leverage their respective strengths. During our literature screening, we found limited studies addressing task division between humans and machines (see also ref. 90). However, some work has explored this approach. For instance, Lee et al.91 developed an interactive AI system that identifies key features in assessments to generate patient-specific analyses. Therapists can then provide feature-based feedback to fine-tune the model for personalized assessments. Greater attention should be given to identifying optimal teaming modes in various clinical areas.

Third, we used the lens of reliability analysis to evaluate the impacts of HMT on diagnostic reliability and its moderators. Future research could explore effect sizes in statistics21, to re-examine our key findings for RQ1 (note: RQ2–RQ4 cannot be addressed using traditional effect sizes). Future research could consider metrics such as diagnostic sensitivity and specificity or clinician workload to provide more comprehensive evaluations of the impacts of HMT on clinicians and medical practice. Also, the regression models presented in Fig. 2D and Fig. 3 are intended for exploratory purposes only, not for explanatory purposes. Our retrospective data cannot confirm their predictive utility. Future research should test the implied empirical associations in more controlled settings.

Fourth, we coded participants’ expertise in the extracted studies based on their original descriptions. However, participants grouped under the same expertise level may still differ across studies, or their expertise may have been defined along different dimensions, such as trainee status (e.g., interns vs. consultants) or professional rank (e.g., residents vs. attending physicians). To reduce potential side effects of this heterogeneity, future research would benefit from adopting a more systematic and standardized approach to defining and measuring human expertise and experience in human–AI teaming.

Fifth, we did not consider other potential moderators, such as AI explainability33 and confidence level of AI outputs35, due to insufficient data for quantitative analysis. We focus on AI explainability for further discussion, as it is widely regarded as a key requirement for fostering trustful and efficient clinician–AI teaming92,93. We noted the mixed empirical findings about AI explainability in the included studies and broader literature. Among the studies we reviewed, only Chanda et al.33 directly compared traditional and explainable AI (XAI) and found that XAI did not improve diagnostic accuracy but did increase clinicians’ confidence in their diagnoses (see also ref. 94). Similarly, Cabitza et al.95 tested a simulated medical AI tool with and without explanations and found that explanations had either no effect or a detrimental effect compared to AI without explanations. Research from other settings also suggests that explanations—particularly when imperfect or poorly designed without a human-centered approach—may merely create an illusory sense of understanding or overconfidence96, or distract professional users from central tasks97,98, and fail to deliver convincing impacts21,99. This implies that more empirical research is needed to clarify the added value of XAI and to develop evidence-based, human-centered XAI techniques within and beyond healthcare settings100.

Finally, our reliability analysis, like most of the included comparative studies or reviews, simplifies the complexity and challenges of HMT in clinical settings, including its dynamics, associated uncertainties, and long-term impacts on clinicians and healthcare organizations14,63,80. These aspects warrant continued research efforts.

Methods

Literature search and screening

We followed the process of PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) to search relevant studies published in English from the dataset of Web of Science. The publication time of studies was set from inception to the date of the last search (May 16, 2023). One researcher used the keywords in Fig. 4 to search the potential publications. We are interested in the impacts of the teaming between humans and AIs on diagnostic tasks. Thus, for machines, we used the keyword “artificial intelligence”. Given that AIs are designed to support and assist humans in HMT, thus relevant keywords such as “support” were included. For diagnostic tasks and reliability metrics, we considered the keywords such as “diagnosis”, “decision”, and “CDSS” and “accuracy”. This initial research resulted in a record of 3191 publications. It is a challenge to extract valid publications and reliability data from scanning these publications, because most of the empirical publications did not provide reliability data of humans and particularly they focused on comparing machine performance against human performance9,101. One researcher reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full-text of these retrieved records (when necessary). Most of the records were excluded for different reasons (see Fig. 4), leaving 31 publications that contain actual diagnostic data of clinicians, real AI systems (all are data-driven, machine learning/deep learning systems), and their teaming. In addition, other two researchers (including one PI) independently checked the reference list of these publications and of certain review papers about AI’s assistive performance (e.g., refs. 35,39) and the papers that cited these publications (for instance, we checked the papers that cite the influential work36 through Google Scholar for more relevant publications). This snowball search involving forward and backward citation searches, which added 21 valid journal papers, not only allows us to identify the missing papers in other databases but also to identify the relevant papers published after our last search (May 16, 2023).

Of note, although some studies provided all reliability data for humans, machines, and HMT, careful inspections indicated that they did not consider real interaction process between humans and machine (e.g., ref. 102), that their metric of accuracy (reliability) is unlike what we and others use (e.g., ref. 103), or that they used simulated AI rather than real AI (e.g., ref. 104). These studies were excluded. We finally have 52 journal papers (see Supplementary Table 2 in the Supplementary Material).

Study characteristics

Two researchers independently coded and extracted reliability data from the final 52 journal papers. Following the coding book (see Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Material) used in previous research (e.g., ref. 39), two researchers independently coded these papers in terms of site (i.e., patient data source), study cohort, disease, clinician number in HMT, clinician expertise, AI type, AI explainability, task type, teaming mode, and number of patients/tasks, as well as human reliability (HR), machine reliability (MR), and observed HMT reliability (see Table 1 and Table 2). Certain coding elements are explained here.

Regarding the teaming mode, some studies might not provide explicit information. If they required human participants to make their own judgments at first or mentioned that their participants should have initial judgments, we coded the teaming mode as “sequential”. If human participants can access the diagnostic cases and corresponding machines’ outputs before their judgments, we coded it “simultaneous”. When no information is provided, we coded it as “unclear”.

For coding expertise level, we used original information provided by these studies’ authors, and we did not attempt to use the same standard (i.e., working experience in years) to match the expertise level across all of the involved studies. We did not contact study authors for additional or unclear information (see also ref. 67). The included studies used different labels and explanations to describe participants’ expertise levels, such as “expert” versus “nonexpert”55, “expert’ versus “novice”105, and “senior” versus ‘junior”106. Following the authors’ original descriptions, we coded groups such as “nonexpert”55, “novices”105, and “junior”106 as “junior”. In some cases, however, explicit information about expertise was not provided, which required us to make reasonable inferences. For example, in one study107, the performance of two ENT physicians (one board-certified and one in-training) was reported as a group, with or without AI assistance, without separate results for each physician. One coder classified the group as “senior”, while the other coded it as “unclear”. Because the board-certified physician could fall into either senior or junior levels, and the in-training physician clearly represented the junior level, we ultimately decided to code this group’s expertise as “unclear”. The potential limitations of our coding are discussed later.

To ensure transparency and reproducibility of our coding results, we made the middle and final coding results publically available (see “Data availability”). The (dis)agreements of the two independent coders are also given. We calculated their inter-rater reliability in certain important coding elements such as clinician expertise (Cohen’s kappa = 0.81) and teaming mode (kappa = 0.73). A senior researcher (P. Liu) reviewed their (in)consistencies, determined the final coding together with the two independent researchers through consensus, and offered suggestions for improving the coding in group meetings.

As shown in Table 1, almost half of these studies (48.1%) evaluated data from China. Among the included studies, 42 studies relied on retrospective data, and nine conducted prospective evaluations through laboratory experiments or real-world settings. The included studies, which in total recruited 1098 clinician participants and comprised a total of 34,893 decision tasks (patient cases or diagnostic tasks), varied considerably (see Table 1). Most of them (57.7%) had few clinician participants in HMT (≤ 10) (e.g., refs. 108,109), while some studies have more than 100 clinician participants (e.g., refs. 33,36). One major reason is that those recruiting few participants had the involvement of human professionals to validate their AI models rather than to focus on clinician-AI collaboration. Also, some studies considered fewer than 100 decision tasks (e.g., ref. 110), while others considered more than 1000 tasks (e.g., ref. 33).

Reliability data extraction and analysis technique

Before explaining our reliability data extraction, it is important to highlight the benefits of reliability-based aggregation approach and reliability-based metrics. Traditional meta-analysis studies adopt certain effect size measures such as Hedges’ g estimate111 to estimate the average effect size from studies addressing similar research questions (e.g., the difference between the treatment and control groups or the relationship between two variables). We chose reliability-based metrics over traditional effect size metrics because they can provide greater interpretability and clinical relevance for human-AI teaming. Whereas effect sizes often yield broad estimates (e.g., small, medium, or large effects), reliability differences and complementarity ratios (i.e., observed HMT reliability divided by ideal HMT reliability) directly indicate whether joint performance surpasses that of either agent alone and quantify the degree of their complementarity. These raw metrics are generally more intuitive for practitioners, clinicians, and decision-makers. They are also scale-independent, enabling more meaningful comparisons of teaming outcomes across diverse clinical domains. With respect to our four research questions, both effect size and reliability-based metrics can address RQ1 (i.e., Does HMT outperform humans?), and they are expected to yield convergent findings (see indirect evidence112). However, reliability-based metrics, which have explanatory and predictive utility, are more suitable for addressing RQ2–RQ4.

For each article, we extracted human reliability, machine reliability, and observed HMT reliability, and calculated ideal HMT reliability based on the equation in Fig. 1. We treated the involved articles as “independent” samples, and more specifically, extracted two levels of reliability data from each article (study-level and condition-level; each data from both datasets was treated as an “independent sample”). Each article might contain a single experimental condition or multiple conditions and thus it may contribute a single data point or multiple data points at the condition level. Here, a “condition” refers to the combination of a teaming mode (sequential vs. simultaneous vs. unclear) and an expertise level (junior vs. senior vs. unclear). For any study involving multiple conditions, we clustered their data points at the study level. Certain articles considered multiple types of medical diagnostics tasks (e.g., multiple diseases). We were not interested in whether the impact of HMT varies for multiple diseases and thus clustered them into a single reliability data point for the sake of simplifying our analysis. Among the included studies, 50 offered a single study-level data point, with two exceptional studies: Nuutinen et al.113 conducted two independent experiments with different sets of human participants and Chanda et al.33 employed two kinds of AI (normal and explainable AI) with different sets of human participants, thus contributed two study-level data points each.

Our focus is on the condition-level data set (teaming mode * expertise level). These conditions have different sets of clinician participants and thus can be treated as “independent” to each. In addition, two studies59,113 considered both teaming modes. Lee et al.59 asked their radiologists to evaluate breast ultrasonography images using the sequential and simultaneous modes, which took place 4 weeks apart for washout. Given their long washout period, we treated data from their two modes as “independent”. Nuutinen et al.113 conducted two experiments to check the two modes with different sets of participants and thus data from their different experiments (i.e., teaming modes) were treated as “independent”.

Finally, we had 54 study-level and 87 condition-level data points for further statistical analysis (using R; see “Code availability”). Study-level data will be used as a robustness check for analysis at the condition level. Also, we weighted the included studies/conditions as a function of their total number of diagnostic tasks; for instance, assuming a single study involving 10 clinicians and 100 patient cases, its weight for study-level data is 1000 (= 10 × 100). Table 2 illustrates reliability data from two articles (please see Supplementary Table 3 for reliability data from all included articles).

Data availability

All data and results are publicly available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/f5djy/?view_only=2018206d192b48b5b663d2abf25e93df.

Code availability

All R codes utilized for statistical analysis are publicly available on the Open Science Framework at https://osf.io/f5djy/?view_only=2018206d192b48b5b663d2abf25e93df.

References

Rahwan, I. et al. Machine behaviour. Nature 568, 477–486 (2019).

Yang, G.-Z. et al. Medical robotics—regulatory, ethical, and legal considerations for increasing levels of autonomy. Sci. Robot. 2, eaam8638 (2017).

Kohn, L. T., Corrigan, J. M. & Donaldson, M. S. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System (National Academies Press, 2000).

Marcus, H. J. et al. The IDEAL framework for surgical robotics: development, comparative evaluation and long-term monitoring. Nat. Med. 30, 61–75 (2024).

Lin, Q. et al. Artificial intelligence-based diagnosis of breast cancer by mammography microcalcification. Fundam. Res. 5, 880–889 (2025).

Moor, M. et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature 616, 259–265 (2023).

Liu, F. et al. A medical multimodal large language model for future pandemics. npj Digit. Med. 6, 226 (2023).

Zhou, S. et al. Large language models for disease diagnosis: a scoping review. npj Artif. Intell. 1, 9 (2025).

Tschandl, P. et al. Comparison of the accuracy of human readers versus machine-learning algorithms for pigmented skin lesion classification: an open, web-based, international, diagnostic study. Lancet Oncol. 20, 938–947 (2019).

Esteva, A. et al. Dermatologist-level classification of skin cancer with deep neural networks. Nature 542, 115–118 (2017).

Drogt, J., Milota, M., van den Brink, A. & Jongsma, K. Ethical guidance for reporting and evaluating claims of AI outperforming human doctors. npj Digit. Med. 7, 271 (2024).

Yang, H. et al. Identification of upper GI diseases during screening gastroscopy using a deep convolutional neural network algorithm. Gastrointest. Endosc. 96, 787–795.e786 (2022).

Jamjoom, A. A. B. et al. Autonomous surgical robotic systems and the liability dilemma. Front. Surg 9, 1015367 (2022).

Lebovitz, S., Lifshitz-Assaf, H. & Levina, N. To engage or not to engage with AI for critical judgments: how professionals deal with opacity when using AI for medical diagnosis. Organ. Sci. 33, 126–148 (2022).

Henry, K. E. et al. Human–machine teaming is key to AI adoption: clinicians’ experiences with a deployed machine learning system. npj Digit. Med. 5, 97 (2022).

Bienefeld, N., Keller, E. & Grote, G. Human-AI teaming in critical care: a comparative analysis of data scientists’ and clinicians’ perspectives on AI augmentation and automation. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e50130 (2024).

Calisto, F. M. G. F. Human-Centered Design of Personalized Intelligent Agents in Medical Imaging Diagnosis. PhD thesis, Universidade de Lisboa (2024).

Cambridge English Dictionary. Complementarity. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/complementarity (n.d.).

American Psychological Association. Complementarity. https://dictionary.apa.org/complementarity (n.d.).

Dellermann, D., Ebel, P., Söllner, M. & Leimeister, J. M. Hybrid intelligence. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 61, 637–643 (2019).

Vaccaro, M., Almaatouq, A. & Malone, T. When combinations of humans and AI are useful: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nat. Hum. Behav. 8, 2293–2303 (2024).

Hemmer, P., Schemmer, M., Kühl, N., Vössing, M. & Satzger, G. Complementarity in human-AI collaboration: concept, sources, and evidence. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2025.2475962 (in press).

Litvinova, Y., Mikalef, P. & Luo, X. Framework for human–XAI symbiosis: extended self from the dual-process theory perspective. J. Bus. Anal. 7, 224–255 (2024).

Jarrahi, M. H. Artificial intelligence and the future of work: human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making. Bus. Horiz. 61, 577–586 (2018).

Ren, Y., Deng, X. & Joshi, K. D. Unpacking human and AI complementarity: insights from recent works. SIGMIS Database 54, 6–10 (2023).

Man, P. M. et al. When conscientious employees meet intelligent machines: an integrative approach inspired by complementarity theory and role theory. Acad. Manag. J. 65, 1019–1054 (2022).

Monteith, S. et al. Differences between human and artificial/augmented intelligence in medicine. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 2, 100084 (2024).

Tikhomirov, L. et al. Medical artificial intelligence for clinicians: the lost cognitive perspective. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e589–e594 (2024).

Dratsch, T. et al. Automation bias in mammography: the impact of artificial intelligence BI-RADS suggestions on reader performance. Radiology 307, e222176 (2023).

Jabbour, S. et al. Measuring the impact of AI in the diagnosis of hospitalized patients: a randomized clinical vignette survey study. JAMA 330, 2275–2284 (2023).

Vicente, L. & Matute, H. Humans inherit artificial intelligence biases. Sci. Rep. 13, 15737 (2023).

Gichoya, J. W. et al. AI pitfalls and what not to do: mitigating bias in AI. Br. J. Radiol. 96, 20230023 (2023).

Chanda, T. et al. Dermatologist-like explainable AI enhances trust and confidence in diagnosing melanoma. Nat. Commun. 15, 524 (2024).

Kiani, A. et al. Impact of a deep learning assistant on the histopathologic classification of liver cancer. npj Digit. Med. 3, 23 (2020).

Krakowski, I. et al. Human-AI interaction in skin cancer diagnosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. npj Digit. Med. 7, 78 (2024).

Tschandl, P. et al. Human–computer collaboration for skin cancer recognition. Nat. Med. 26, 1229–1234 (2020).

Wang, Z., Wei, L. & Xue, L. Overcoming medical overuse with AI assistance: an experimental investigation. J. Health Econ. 103, 103043 (2025).

Vasey, B. et al. Association of clinician diagnostic performance with machine learning–based decision support systems: a systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open 4, e211276 (2021).

Dan, Q. et al. Diagnostic performance of deep learning in ultrasound diagnosis of breast cancer: a systematic review. npj Precis. Oncol. 8, 21 (2024).

Nakagawa, K. et al. AI in pathology: what could possibly go wrong?. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 40, 100–108 (2023).

Rajpurkar, P. & Lungren, M. P. The current and future state of AI interpretation of medical images. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 1981–1990 (2023).

Te’eni, D. et al. Reciprocal human-machine learning: a theory and an instantiation for the case of message classification. Manag. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2022.03518 (in press).

Goddard, K., Roudsari, A. & Wyatt, J. C. Automation bias: a systematic review of frequency, effect mediators, and mitigators. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 19, 121–127 (2012).

Kostick-Quenet, K. M. & Gerke, S. AI in the hands of imperfect users. npj Digit. Med. 5, 197 (2022).

Almaatouq, A., Alsobay, M., Yin, M. & Watts, D. J. Task complexity moderates group synergy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2101062118 (2021).

Bansal, G. et al. Does the whole exceed its parts? The effect of AI explanations on complementary team performance. In Proc. 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 81 (ACM, 2021).

Steyvers, M., Tejeda, H., Kerrigan, G. & Smyth, P. Bayesian modeling of human–AI complementarity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2111547119 (2022).

Rosenbacke, R., Melhus, Å & Stuckler, D. False conflict and false confirmation errors are crucial components of AI accuracy in medical decision making. Nat. Commun. 15, 6896 (2024).

Beck, H. P., McKinney, J. B., Dzindolet, M. T. & Pierce, L. G. Effects of human—machine competition on intent errors in a target detection task. Hum. Factors 51, 477–486 (2009).

Wies, C., Hauser, K. & Brinker, T. J. Reply to: False conflict and false confirmation errors are crucial components of AI accuracy in medical decision making. Nat. Commun. 15, 6897 (2024).

Jamieson, G. A., Skraaning, G. & Joe, J. The B737 MAX 8 accidents as operational experiences with automation transparency. IEEE Trans. Hum. -Mach. Syst. 52, 794–797 (2022).

Calisto, F. M. et al. Assertiveness-based agent communication for a personalized medicine on medical imaging diagnosis. In Proc. 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 13 (ACM, 2023).

Zhang, S. et al. Rethinking human-AI collaboration in complex medical decision making: a case study in sepsis diagnosis. In Proc. 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 445 (ACM, 2024).

Steyvers, M. & Kumar, A. Three challenges for AI-assisted decision-making. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 19, 722–734 (2024).

Rondonotti, E. et al. Artificial intelligence-assisted optical diagnosis for the resect-and-discard strategy in clinical practice: the artificial intelligence BLI Characterization (ABC) study. Endoscopy 55, 14–22 (2022).

Han, P. et al. Improving early identification of significant weight loss using clinical decision support system in lung cancer radiation therapy. JCO Clin. Cancer. Inform. 944–952 (2021).

Buçinca, Z., Malaya, M. B. & Gajos, K. Z. To trust or to think: cognitive forcing functions can reduce overreliance on AI in AI-assisted decision-making. Proc. ACM Hum. -Comput. Interact. 5, 188 (2021).

Agarwal, N., Moehring, A., Rajpurkar, P. & Salz, T. Combining Human Expertise with Artificial Intelligence: Experimental Evidence from Radiology (MIT Blueprint Labs, 2024).

Lee, S. E. et al. Differing benefits of artificial intelligence-based computer-aided diagnosis for breast US according to workflow and experience level. Ultrasonography 41, 718–727 (2022).

Barinov, L. et al. Impact of data presentation on physician performance utilizing artificial intelligence-based computer-aided diagnosis and decision support systems. J. Digit. Imaging 32, 408–416 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. Clinical value of artificial intelligence in thyroid ultrasound: a prospective study from the real world. Eur. Radiol. 33, 4513–4523 (2023).

Wei, X. et al. Artificial intelligence assistance improves the accuracy and efficiency of intracranial aneurysm detection with CT angiography. Eur. J. Radiol. 149, 110169 (2022).

Wang, W., Gao, G. & Agarwal, R. Friend or foe? Teaming between artificial intelligence and workers with variation in experience. Manag. Sci. 70, 5753–5775 (2024).

Logg, J. M., Minson, J. A. & Moore, D. A. Algorithm appreciation: people prefer algorithmic to human judgment. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 151, 90–103 (2019).

Yu, F. et al. Heterogeneity and predictors of the effects of AI assistance on radiologists. Nat. Med. 30, 837–849 (2024).

Brejnebøl, M. W. et al. Interobserver agreement and performance of concurrent AI assistance for radiographic evaluation of knee osteoarthritis. Radiology 312, e233341 (2024).

Han, R. et al. Randomised controlled trials evaluating artificial intelligence in clinical practice: a scoping review. Lancet Digit. Health 6, e367–e373 (2024).

Lehman, C. D. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of digital screening mammography with and without computer-aided detection. JAMA Intern. Med. 175, 1828–1837 (2015).

Ranisch, R. Scapegoat-in-the-loop? Human control over medical AI and the (mis)attribution of responsibility. Am. J. Bioeth. 24, 116–117 (2024).

Boor, P. Deep learning applications in digital pathology. Nat. Rev. Nephrol 20, 702–703 (2024).

Rajpurkar, P. et al. CheXaid: Deep learning assistance for physician diagnosis of tuberculosis using chest x-rays in patients with HIV. npj Digit. Med. 3, 115 (2020).

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B. & Walker, S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 67, 1–48 (2015).

Kim, J. S., Colombatto, C. & Crockett, M. J. Goal inference in moral narratives. Cognition 251, 105865 (2024).

Barr, D. J., Levy, R., Scheepers, C. & Tily, H. J. Random effects structure for confirmatory hypothesis testing: Keep it maximal. J. Mem. Lang. 68, 255–278 (2013).

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J. & Anderson, R. E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th edn (Pearson, 2014).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 19, 716–723 (1974).

Anthony, C., Bechky, B. A. & Fayard, A.-L. “Collaborating” with AI: taking a system view to explore the future of work. Organ. Sci. 34, 1672–1694 (2023).

Schmutz, J. B., Outland, N., Kerstan, S., Georganta, E. & Ulfert, A.-S. AI-teaming: redefining collaboration in the digital era. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 58, 101837 (2024).

Yin, J., Ngiam, K. Y., Tan, S. S.-L. & Teo, H. H. Designing AI-based work processes: how the timing of AI advice affects diagnostic decision making. Manag. Sci. 71, 8995–9868 (2025).

Jussupow, E., Spohrer, K., Heinzl, A. & Gawlitza, J. Augmenting medical diagnosis decisions? An investigation into physicians’ decision-making process with artificial intelligence. Inf. Syst. Res. 32, 713–735 (2021).

Le, E. P. V., Wang, Y., Huang, Y., Hickman, S. & Gilbert, F. J. Artificial intelligence in breast imaging. Clin. Radiol. 74, 357–366 (2019).

Barnes, A. J., Zhang, Y. & Valenzuela, A. AI and culture: culturally dependent responses to AI systems. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 58, 101838 (2024).

Gupta, P., Nguyen, T. N., Gonzalez, C. & Woolley, A. W. Fostering collective intelligence in human–AI collaboration: laying the groundwork for COHUMAIN. Top. Cogn. Sci. 172, 189–216 (2025).

Vanneste, B. S. & Puranam, P. Artificial intelligence, trust, and perceptions of agency. Acad. Manage. Rev. 50, 726–744 (2025).

Banja, J. D., Hollstein, R. D. & Bruno, M. A. When artificial intelligence models surpass physician performance: medical malpractice liability in an era of advanced artificial intelligence. J. Am. Coll. Radiol. 19, 816–820 (2022).

Pearce, F. J. et al. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in trials of artificial intelligence health technologies: a systematic evaluation of ClinicalTrials.gov records (1997-2022). Lancet Digit. Health. 5, e160–e167 (2023).

Christodoulou, E. et al. False promises in medical imaging AI? Assessing validity of outperformance claims. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.04720 (2025).

Kim, T. et al. Transfer learning-based ensemble convolutional neural network for accelerated diagnosis of foot fractures. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 46, 265–277 (2023).

Wekenborg, M. K., Gilbert, S. & Kather, J. N. Examining human-AI interaction in real-world healthcare beyond the laboratory. npj Digit. Med. 8, 169 (2025).

Susanto, A. P., Lyell, D., Widyantoro, B., Berkovsky, S. & Magrabi, F. Effects of machine learning-based clinical decision support systems on decision-making, care delivery, and patient outcomes: a scoping review. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 30, 2050–2063 (2023).

Lee, M. H., Siewiorek, D. P., Smailagic, A., Bernardino, A. & Badia, S. B. B.i. A human-AI collaborative approach for clinical decision making on rehabilitation assessment. In Proc. 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 392 (ACM, 2021).

Hadweh, P. et al. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in intensive care medicine: critical recalibrations from rule-based systems to frontier models. J. Clin. Med. 14, 4026 (2025).

Calisto, F. M., Abrantes, J. M., Santiago, C., Nunes, N. J. & Nascimento, J. C. Personalized explanations for clinician-AI interaction in breast imaging diagnosis by adapting communication to expertise levels. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. St. 197, 103444 (2025).

Dong, Z. et al. Explainable artificial intelligence incorporated with domain knowledge diagnosing early gastric neoplasms under white light endoscopy. npj Digit. Med. 6, 64 (2023).

Cabitza, F. et al. Rams, hounds and white boxes: Investigating human–AI collaboration protocols in medical diagnosis. Artif. Intell. Med. 138, 102506 (2023).

Ostinelli, M., Bonezzi, A. & Lisjak, M. Unintended effects of algorithmic transparency: the mere prospect of an explanation can foster the illusion of understanding how an algorithm works. J. Consum. Psychol. 35, 203–219 (2025).

Paleja, R., Ghuy, M., Arachchige, N. R., Jensen, R. & Gombolay, M. The utility of explainable AI in Ad Hoc human-machine teaming. In Proc. 35th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 610–623 (NeurIPS, 2021).

Spitzer, P. et al. Imperfections of XAI: phenomena influencing AI-assisted decision-making. ACM Trans. Interact Intell. Syst. 15, 17 (2025).

Rieger, T., Onnasch, L., Roesler, E. & Manzey, D. Why highly reliable decision support systems often lead to suboptimal performance and what we can do about it. IEEE Trans. Hum.-Mach. Syst. 55, 736–745 (2025).

Herrera, F. Reflections and attentiveness on eXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI). The journey ahead from criticisms to human–AI collaboration. Inf. Fusion. 121, 103133 (2025).

Reverberi, C. et al. Experimental evidence of effective human–AI collaboration in medical decision-making. Sci. Rep. 12, 14952 (2022).

He, L.-T. et al. A comparison of the performances of artificial intelligence system and radiologists in the ultrasound diagnosis of thyroid nodules. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 18, 1369–1377 (2022).

Lin, Z.-W., Dai, W.-L., Lai, Q.-Q. & Wu, H. Deep learning-based computed tomography applied to the diagnosis of rib fractures. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 16, 100558 (2023).

Goddard, K., Roudsari, A. & Wyatt, J. C. Automation bias: empirical results assessing influencing factors. Int. J. Med. Inform. 83, 368–375 (2014).

Tang, D. et al. A novel model based on deep convolutional neural network improves diagnostic accuracy of intramucosal gastric cancer (with video). Front. Oncol. 11, 622827 (2021).

Yuan, X.-L. et al. Artificial intelligence for diagnosing gastric lesions under white-light endoscopy. Surg. Endosc. 36, 9444–9453 (2022).

Chen, Y.-S. et al. Improving detection of impacted animal bones on lateral neck radiograph using a deep learning artificial intelligence algorithm. Insights imaging 14, 43 (2023).

Cho, E., Kim, E.-K., Song, M. K. & Yoon, J. H. Application of computer-aided diagnosis on breast ultrasonography: evaluation of diagnostic performances and agreement of radiologists according to different levels of experience. J. Ultrasound Med. 37, 209–216 (2018).

Choi, J. S. et al. Effect of a deep learning framework-based computer-aided diagnosis system on the diagnostic performance of radiologists in differentiating between malignant and benign masses on breast ultrasonography. Korean J. Radiol. 20, 749–758 (2019).

He, X. et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence for diagnosing early gastric cancer by magnifying image-enhanced endoscopy: a multicenter diagnostic study (with videos). Gastrointest. Endosc. 95, 671–678.e674 (2022).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T. & Rothstein, H. R. Introduction to Meta-Analysis (Wiley, 2021).

Wickens, C. D., Hutchins, S., Carolan, T. & Cumming, J. Effectiveness of part-task training and increasing-difficulty training strategies: a meta-analysis approach. Hum. Factors 55, 461–470 (2013).

Nuutinen, M. et al. Aid of a machine learning algorithm can improve clinician predictions of patient quality of life during breast cancer treatments. Health Technol. 13, 229–244 (2023).

Hu, H.-T. et al. Artificial intelligence assists identifying malignant versus benign liver lesions using contrast-enhanced ultrasound. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 36, 2875–2883 (2021).

Lu, J. et al. Identification of early invisible acute ischemic stroke in non-contrast computed tomography using two-stage deep-learning model. Theranostics 12, 5564–5573 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Major Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant numbers T2192933, T2192932, and T2192931).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions