Abstract

Hearing and vision loss is common among people with dementia (PwD) in long-term care (LTC), affecting quality of life and dementia-related outcomes. Up to 90% of PwD in LTC have hearing loss and over 40% vision loss, yet detection and management are often inadequate. Staff often lack training, environments may be ‘sensory unfriendly’, and trial evidence is limited. The SENSE-Cog Residential Care pilot trial evaluated the feasibility of a structured sensory intervention and its potential for a future definitive trial. This cluster-randomised feasibility study was conducted across nine LTC facilities in Ireland, randomised to care as usual or an intervention comprising personalised sensory support, staff training, environmental audit, and mapping sensory care provision. Feasibility outcomes included recruitment, retention, uptake, safety, and data collection. Potential efficacy outcomes included quality of life, cognition, frailty, comorbidity, behavioural symptoms, and sensory health. Of 10 invited facilities, 9 participated, recruiting 27 PwD within 2 months; 26 remained at 3 months. Twelve residents received sensory assessments, leading to 12 glasses, 4 hearing aids, and 6 listening devices. Training was delivered to 42 staff, including sensory champions, and was rated highly acceptable. At follow-up, 67% wore glasses, 75% used hearing aids, and 17% used listening devices. Findings support progression to a full-scale RCT. Trial registration: ISRCTN, ISRCTN14462472. Registered 24 February 2022, https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN14462472.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In Ireland, nearly 65,000 people are estimated to have dementia, with over 30% residing in long-term care facilities (LTCFs)1. LTCFs are residential care settings providing 24-h nursing and personal care on a long-term basis, commonly referred to as nursing homes in Ireland. Throughout this paper, we use the term ‘people with dementia in long-term care’ (PwD in LTC) to refer to this group, distinguishing them from community-dwelling PwD. Among PwD in LTC, sensory impairments are highly prevalent, with research showing that 75–90% experience significant hearing loss2 and over 40% have substantial vision loss3. These rates far exceed those seen in PwD living at home3.

Hearing loss among PwD in LTC is influenced by ageing, concurrent health conditions, and the LTC environment4. It exacerbates social isolation, communication difficulties, and cognitive decline5. Similarly, vision loss, affecting over 40% of PwD in LTC, is three times as prevalent as among PwD living at home, hinders daily activities, increases fall risk, and accelerates cognitive and physical decline6. PwD in LTC with dual sensory impairments fare worse, experiencing greater communication challenges, loneliness, neuropsychiatric symptoms, reduced quality of life, and less independence in activities of daily living7,8.

Despite the high prevalence of sensory impairments, detection and management in LTC are inadequate due to insufficient sensory health screenings, limited staff training, and challenges in identifying sensory deficits in cognitively impaired individuals3,9,10. Additionally, many LTC environments are ‘sensory unfriendly,’ characterised by poor lighting and noise levels that negatively impact residents’ cognitive, behavioural, and emotional well-being11,12. Barriers to optimal sensory care include under-detection of hearing and vision loss, insufficient use of hearing aids and other assistive devices, a lack of staff confidence in providing ear and eye care, and the need for improved staff training and environmental adjustments13,14. Poor maintenance of sensory aids and a lack of support due to staff unawareness and unclear referral pathways further exacerbate these issues15,16,17. Additionally, identifying sensory deficits in PwD can be challenging due to their limited awareness, poor reporting of deficits, and symptom overlap with dementia (Aldridge and Newsome)18.

An international study revealed that while LTC staff were aware of sensory health issues in PwD in LTC, there were significant gaps in care practices. Staff expressed a desire to improve sensory care19. A systematic review also highlighted the scarcity of large-scale randomised controlled trials (RCTs) on sensory interventions for PwD in LTC20. Existing evidence suggests that sensory devices alone are insufficient without personalised rehabilitation plans, as emphasised by international guidelines21,22.

The SENSE-Cog RCT23 recently evaluated a Sensory Support Intervention (SSI) for 252 community-dwelling individuals with mild-to-moderate dementia and sensory impairments across five European countries. The SSI included home-based hearing and vision rehabilitation supported by a sensory therapist. The study demonstrated short-term improvements in quality of life but no sustained long-term benefits. These findings give us information about people living at home and provide a foundation for testing sensory support for PwD in LTC, where evidence remains limited.

In this study, we adapted the SENSE-Cog SSI, initially designed for people with dementia living at home24, to address the specific needs of PwD in LTC. Compared with community-dwelling PwD, PwD in LTC are typically older, have more comorbidities, and present with more advanced dementia25. Thus, the adapted intervention shifted focus beyond individual-level behavioural change to also encompass staff, environmental, and organisational levels informed by our theoretical framework, the Sensory Cognitive Model of Place26. We therefore omitted the goal-setting component aimed at developing sensory self-management skills (e.g., cleaning hearing aids) and added staff-focused components, including sensory-cognitive training to create intervention buy-in and amelioration of environmental sensory challenges. Table 1 summarises the modifications to the SSI.

Using a feasibility pilot cluster RCT, we evaluated the adapted SSI for residential care settings (SSI-RC) to inform a subsequent full-scale RCT. Following the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for developing complex interventions27, the study aimed to: (i) assess the operational aspects of the study, including recruitment, retention, data collection and design; (ii) evaluate the feasibility, acceptability and fidelity of the intervention; (iii) test a battery of potential efficacy outcomes; and (iv) determine whether progression to a full trial is warranted.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the PwD in LTC include dementia type, dementia diagnosis and sensory profile, as shown in Table 2.

To gain insight into the care provided for sensory health in long-term care (LTC) facilities for PwD in LTC in Ireland, a survey was conducted with facility managers and directors of nursing. A total of 39 responses were received, with 34 included in the analysis. Five responses were excluded due to incomplete information. Among the 34 valid responses, 68% (n = 26) were from facility owners or managers, 36% (n = 6) were from senior nursing staff (assistant directors of nursing and clinical nurse managers), and 18% (n = 3) were from care assistants. Most facilities (70%, n = 23) were in rural areas, while 30% (n = 10) were in urban locations28,29.

Regarding sensory care practices, staff in most facilities reported checking the functionality of hearing aids. Specifically, 100% (n = 27) asked residents directly, 96% (n = 26) checked the aids themselves, and 89% (n = 24) consulted family members. For vision care, similar practices were observed: 100% (n = 27) of staff asked residents if their glasses were correct, 93% (n = 25) checked the glasses directly, and 85% (n = 23) consulted family members. However, dedicated staff for these tasks were limited. A staff member specifically assigned to manage hearing aids was reported in 64% (n = 18) of facilities, but only 13% (n = 3) had someone designated to oversee residents’ glasses.

The provision of professional hearing care was limited. Only 27% (n = 7) of facilities reported visits from hearing professionals for hearing aid maintenance, while 48% (n = 13) received visits for hearing screening or testing. Most facilities (75%, n = 20) reported that residents underwent hearing assessments outside the facility. In contrast, vision care was more readily accessible: 54% (n = 14) of facilities received visits from vision professionals for glasses maintenance, and 88% (n = 23) had access to vision screening or testing. Despite this, 85% (n = 24) of facilities indicated that residents received vision tests off-site.

Environmental management to support hearing needs was notably lacking. Only 15% (n = 4) of facilities had a staff member responsible for monitoring the environment for hearing-related challenges, and just over half (54%, n = 15) made environmental modifications to reduce the impact of hearing loss. In contrast, vision care measures were stronger: nearly all facilities (96%, n = 26) implemented environmental adjustments to mitigate the effects of vision loss, and 46% (n = 12) had dedicated staff overseeing environmental factors impacting residents’ vision28,29.

Feasibility of the study procedures

Based on the modified ACCEPT checklist (Table 3), 16 of 24 metrics exceeded the targets, 5 required modifications and 2 were rejected due to local contextual issues.

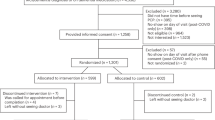

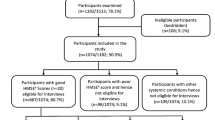

The recruitment target of 10 LTCFs was met within 8 months, before final approvals, with most facilities being urban and publicly operated, which resulted in limited geographic and facility-type diversity (1 rural, 2 private, and 2 voluntary sector facilities). Twenty-seven PwD in LTC (mean, n = 3 per facility) were recruited, exceeding the rate target of 13.5/month yet falling short of the target of five PwD in LTC per facility (see supplementary material 5). Twenty-seven staff (mean, n = 3 per facility) were also recruited (see supplementary material 7 for staff demographics), and all facilities consented to randomisation. Retention was high: 100% facility retention (all 9 randomised facilities completed the protocol), 96% participant retention at 3 months (26 remained; 1 death unrelated to the study), and 95% retention of sensory champions (16 of 17 remained). Thus, randomisation, recruitment, and retention targets were met or exceeded for LTCFs, PwD in LTC and staff.

Intervention fidelity

As shown in Table 3, 100% (n = 4) of the facilities completed Levels 1, 2, and 4 of the intervention, while 25% (n = 1) completed Level 3.

In the intervention arm, 12 persons with dementia (PwD) in LTC were enroled. As part of the resident-level component, level 1, hearing aids were provided to 33% (n = 4) of PwD in LTC, while 50% (n = 6) received listening devices. The audiologist did not recommend hearing aids for 75% (n = 8) of residents—due to poor test responses (63%, n = 5), anticipated acclimatisation issues (25%, n = 2), and minimal hearing deficits (13%, n = 1). At 3-month follow-up, 75% (n = 3) of those with hearing aids continued using them (one was misplaced), whereas only 17% (n = 1) persisted with listening devices. All 12 residents were prescribed glasses, with 67% (n = 8) still using them at follow-up (see supplementary material 8).

The staff-level component, level 2, involved four general staff training sessions with 42 care staff. Additionally, six sensory champion training sessions were conducted, with eight sensory champions participating. Five of these sessions were conducted in person at the LTC facility, while one was conducted online. The average duration of each sensory champion session was 100 min, with 60% (n = 3) of the sessions completed without breaks. The sensory champions included nine care assistants and one nurse. Adherence to the personal sensory plan (PSP) as outlined in the training was observed in 80% (n = 8) of the champions.

Throughout the 12-week study period, sensory champions had an average of seven contacts (both planned and ad hoc) with the research therapist via in-person meetings, video calls, telephone calls, and email exchanges. These interactions occurred with 80% (n = 8) of the champions. Common issues raised during these interactions included: delays in completing the PSP due to delays in the fitting of sensory devices (38%, n = 3), miscommunication between sensory champions and facility managers regarding sensory device delivery dates (38%, n = 3), and difficulty finding time to complete intervention tasks (13%, n = 1). Additional challenges included difficulty communicating with the second sensory champion due to opposite shifts (25%, n = 2) and challenges implementing changes recommended by the sensory environment audit (SEA-NH), such as structural changes (25%, n = 2). Champions in some facilities found these changes impractical or prohibited (e.g., painting walls for better colour contrast). Another 25% (n = 2) of champions cited busy work schedules as a barrier to adhering to the intervention.

For the environmental component, level 3, all four facilities completed the initial sensory environment audit after sensory champion training, with 75% (n = 3) completing a 3-month follow-up. Champions found the audit straightforward. Only one facility implemented changes—staff spoke more quietly in groups to reduce noise for sensitive residents—while another considered, but did not enact, dishware colour changes for improved food contrast. In the three facilities with no changes, champions cited a lack of facility ownership (notably in two publicly operated sites) as a barrier.

Finally, the organisational-support level, all four facilities had access to a vision care provider for regular check-ups; however, only one facility (25%) had a dedicated hearing care provider, with publicly operated facilities offering hearing care on an as-needed basis (see supplementary material 9).

Acceptability of the intervention

Care notes recorded the rates of deaths, hospitalisations, and falls among participating PwD in LTC. Two falls occurred in intervention LTCFs, while CAU facilities reported one hospitalisation and one death. No adverse events were attributed to the intervention.

Key elements of trial design

The study provided essential data for designing a definitive trial. As shown in Table 3, recruitment targets for facilities, staff, and residents met acceptability thresholds, indicating that recruitment methods can be scaled. Regarding the logistics circuit, the study outlined the timeline from baseline to receiving sensory devices. On average, it took 6 days to randomise facilities (SD 2.5, range 5); hearing aids and listening devices were received in 76.7 days (SD = 16.2, range = 34); and glasses in 59.5 days (SD = 7.7, range = 19). This meant that for some residents, particularly those awaiting hearing aids, there was limited time to acclimatise before the 3-month follow-up. This was largely due to temporary service and supply chain delays. Clinical recommendations indicate that acclimatisation typically takes 6 to 12 weeks, and up to 4 months for some individuals30,31,32. To account for this, a future definitive trial will incorporate a 6-month follow-up period to ensure adequate acclimatisation and assessment of intervention impact. With data completion rates exceeding targets, the outcomes battery was validated for relevance and reliability. The study also identified local contextual issues, such as low implementation rates of environmental audit changes. Additionally, it informed sample size estimates and confirmed the suitability of staff training materials for effective intervention delivery.

Data missingness

At baseline, most measures were complete, except for 6.7% missing data on the Veterans’ Affairs Low Vision Visual Functioning and Global Deterioration Scale in the CAU group, and 16.7% missing on DEM QoL-Everyday Activities in the intervention group. By follow-up, missing data in the control group increased to 6.7% across several measures, while quality of life in the intervention group had 25.0% missing data (see supplementary material 10).

Exploratory efficacy outcomes

Table 4 displays exploratory efficacy outcomes for PwD in LTC. At 3 months, the intervention group demonstrated significant improvements in DEM-QOL-Feelings, DEM-QOL-Memory, DEM-QOL-Everyday, and DEM-QOL-Total scores, while changes in Qol-AD, Engagement and Independence in Dementia Questionnaire (EID-Q), Hearing Handicap Inventory for the Elderly—Proxy version (HHIE-P), and Veteran’s Affairs Low Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire—Proxy version (VA-LV-VFQ-P) were not significant.

Staff outcomes

Data completion rates for the KAP and Training Acceptability Rating Scale (TARS) met the ACCEPT criteria, as shown in Table 3. Due to the small number of participants, significance testing was not conducted, however, descriptive statistics are presented in supplementary material 11.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and tolerability of a hearing and vision support intervention for PwD in LTC, referred to as SSI-RC, while assessing the operational aspects for a future RCT. Most feasibility and acceptability criteria were met, supporting the viability of a definitive RCT, with some adjustments to address identified challenges.

The trial design proved feasible, with minor protocol deviations such as missing data for one sensory champion and version control issues with consent forms. These deviations were quickly resolved without compromising data integrity. However, delays in follow-up assessments due to structural changes in audiology services and technical issues with listening devices highlighted a need for improved scheduling in future trials. While these delays did not affect data validity, refined time management strategies, including robust scheduling procedures, will be necessary to prevent disruptions to follow-up timelines and ensure timely delivery of equipment33,34,35,36.

The study successfully recruited LTCFs, meeting the pre-specified rate of 1.5 facilities per month, with 12 facilities recruited over 8 months37. Despite one facility closing before randomisation, the study met recruitment targets, consistent with previous LTC trials38.

Staff recruitment exceeded targets, crucial for implementing the intervention and highlighting the importance of strong staff engagement. Similarly, resident recruitment surpassed the goal, with 13.5 participants enroled per month, demonstrating the feasibility of engaging residents in such interventions. Randomisation was well-accepted by facilities, reflecting their willingness to participate in the trial structure.

Intervention fidelity was high, with 100% engagement with key components (e.g., device delivery and staff attendance). However, environmental modifications per the sensory environment audit were implemented in only 25% of cases; publicly operated facilities faced structural barriers (e.g., wall painting restrictions requiring external approval). Future audits will be adapted to focus on practical, non-structural recommendations to enhance feasibility across both publicly and privately operated facilities. In addition, to improve staff training uptake in a definitive trial, each facility will be consulted on optimal scheduling to ensure coverage of staff working on both day and night shifts.

Device adherence was good overall—75% for hearing aids and 67% for vision aids—yet maintaining consistent use was challenging. As adherence was based on sensory champion reports of general device wear, this pragmatic approach provided a consistent measure but did not capture detailed patterns of use. With no agreed definitions of optimal hearing aid use for PwD, and even less for PwD in LTC, thresholds remain undefined. Evidence from community-dwelling PwD suggests consistent hearing aid use is linked with better quality of life39,40, but further work is needed to establish LTCF-specific thresholds. Participants and staff also struggled to integrate devices into daily routines, echoing prior studies41. For hearing aids specifically, Hooper et al.42 demonstrated that adherence is best conceptualised as a multidimensional construct combining objective wear-time with subjective data (e.g., diaries and logbooks). Building on these insights, a definitive trial will seek to establish adherence thresholds specific to LTCFs and adopt a multidimensional approach to measuring hearing aid use. To further support adherence, future trials should also include family care partner training and regular follow-ups to help integrate devices more effectively into daily routines.

The intervention’s tolerability was good, with no serious adverse events (SAEs), demonstrating its safety for use in this population and supporting its potential for broader implementation in future trials.

Several limitations were identified. Study start-up (SSU) delays significantly shortened the trial duration, affecting scheduling and participant involvement. Although data integrity remained intact, more realistic study start-up timelines are needed to prevent similar issues in future trials.

Recruitment was predominantly skewed toward public, urban LTCFs, limiting the findings’ generalisability43. Future recruitment efforts may use stratified recruitment of facilities (by ownership type and location) to improve the representativeness and applicability of results44. Moreover, the lack of standardised eligibility criteria may have contributed to recruitment variability; future trials should adopt clearer eligibility guidelines to ensure recruitment consistency and transparency.

Challenges with environmental modifications and device usage also indicated the need for additional caregiver involvement and flexible intervention components to enhance sustainability.

The findings suggest that the hearing and vision support intervention is suitable for a definitive RCT, with adjustments. Key improvements include refining scheduling procedures, adapting the sensory audit for more feasible recommendations, and expanding recruitment strategies for greater diversity among LTCF types. Enhanced caregiver training and follow-up support could improve intervention adherence and sustainability.

A future trial should address these limitations, particularly study start-up delays45 and incorporate strategies to overcome barriers to environmental modifications and device use. Moreover, innovative approaches to address the multi-component nature of the intervention and understand the relative contribution of each component should be considered, such as a multiphase optimisation strategy (MOST). MOST is a framework for developing, optimising, and evaluating multicomponent behavioural interventions using principles from engineering and experimental design46. These adjustments will improve the efficiency and generalisability of the trial, yielding more robust findings.

Specifically, in the first phase of MOST, the preparation phase, we will focus on synthesising findings from this study to prioritise candidate intervention components, including sensory assessment and device prescription, staff training, environmental modifications, and organisational change, each targeting different aspects of the outcomes. We will clarify the theoretical mechanisms to explain how each component is expected to influence outcomes. Practical considerations, such as participant adherence, severity of sensory impairment, intervention dosage, feasibility of multi-modal delivery, and resource constraints, will also be addressed.

In sum, this feasibility study supports advancing the hearing and vision support intervention to a definitive RCT, with modifications to trial procedures, recruitment strategies, and scheduling. The intervention demonstrated high feasibility, acceptability, and tolerability; addressing challenges will improve trial efficiency and impact. With these changes, the intervention has strong potential to enhance care for people with dementia in long-term care.

Methods

This three-month pilot feasibility cluster RCT (cRCT) shortened from 6 months due to approval delays45, compared nine LTC facilities (LTCFs) randomised to either care as usual (CAU) or a multi-component SSI for Residential Care (SSI-RC) plus CAU. The SSI-RC, adapted from the home-based SENSE-Cog SSI41, comprised four components: (1) personalised hearing and vision support for residents, led by sensory champions; (2) staff training in sensory-cognitive health; (3) the creation of a sensory-friendly environment; and (4) an assessment of existing care pathways with hearing and vision care providers (see Table 5). The SSI-RC was developed via systematic mapping and stakeholder workshops21. Ethical approval was obtained, and reporting adhered to CONSORT and TIDieR guidelines (see supplementary materials 1 and 2). Study flow is provided in Fig. 1 below. The study was reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at Trinity College Dublin on 09/04/2024 (Reference: 240101).

Sense-Cog Residential Care study flow. Data on national LTC facility statistics from Health Information and Quality Authority47 and Dementia Services Information and Development Centre (2015)48.

Study setting/clusters

We aimed to recruit 8–15 LTCFs in Ireland caring for PwD in LTC, facilitated by Nursing Homes Ireland (NHI) and the HRB Clinical Trials Network. This number of facilities was pragmatically chosen to accommodate the duration and size of the study while ensuring representation across facility types. Previous feasibility studies have included ten LTCFs29. Facilities were pre-screened using Health Information and Quality Authority quality reports, with eligibility criteria detailed in supplementary material 3. Although the original goal was to randomise 8–15 facilities over 8 months, SSU delays reduced the recruitment window to 2 months, shifting the focus to recruitment rate evaluation45.

Participants and recruitment

After screening residents, the Director of Nursing (DON) facilitated researcher discussions with staff, residents, and families about study participation. The DON assessed and verified residents’ eligibility to participate according to the study criteria. Written informed consent was obtained from participants with capacity, and assent was provided by a consultee for those lacking capacity.

Outcome measures

A range of measures assessing health, cognition, and quality of life were used to evaluate the acceptability and feasibility of a potential outcome battery for a definitive trial. Quality of life was assessed with the Quality of Life for Adults with Dementia (QoL-AD) scale35 and DEM-QOL suite36, cognitive and functional status with the 6-item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT)49, Functional Assessment Staging Tool50, and Global Deterioration Scale51. While the 6-CIT has been primarily validated in memory clinic and hospital settings, it was chosen here as a brief and pragmatic screening tool as it minimises burden on residents and indirectly on staff by reducing administration time. The test was administered verbally by the researcher. The 6-CIT does not require reading or writing, so vision is not critical. However, to accommodate residents’ hearing loss, residents were asked to wear their sensory devices during testing, with instructions repeated and written prompts provided as needed. Frailty and comorbidities were assessed with the Clinical Frailty Scale52 and Modified CIRS53; and behavioural symptoms with the Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home54. Sensory function was assessed with the HHIE-P55 and VA-LV-VFQ-P56. General health was measured with the EQ-5D-5L57, yielding utility scores for Quality-Adjusted Life Years calculations, and engagement and independence with the EID-Q58. A pilot-specific tool collected data on residents’ healthcare use for cost analysis.

Randomisation

Facilities were randomly allocated 1:1 using a computer-generated minimisation programme after all eligible residents had consented, been registered, and completed baseline assessments. No stratification criteria were applied due to the small sample size. Facility staff and researchers were unblinded, as the study focused on feasibility, but future trials should consider an observer-blind design.

Data collection and outcomes

To systematically guide decisions on whether to accept, modify, or reject components of our study protocol for informing a definitive trial, we used a modified version of the ACCEPT checklist59, following the guidelines provided by Thabane et al. for reporting feasibility60. A priori criteria and operational definitions for feasibility, acceptability, and tolerability are outlined in Table 3. To facilitate decision-making regarding progression to a definitive RCT, we applied a traffic light system (green/amber/red), as recommended by the MRC Hubs for Trials Methodology Research. Since there are no predefined meanings assigned to each colour within the traffic light system61, the decision to recommend a definitive RCT was based on a careful evaluation of both the feasibility and acceptability outcomes indicated by the system, alongside an assessment of pragmatic and methodological factors. To explore the feasibility of trial-based cost-effectiveness analysis and to inform a power calculation for a decision economic evaluation, feasibility and acceptability of economic outcomes (i.e., EQ-5D-5L and measures of resource use) are assessed.

Feasibility was operationalised by asking the question: ‘Can it work?’62. The feasibility parameters included: eligibility criteria, recruitment and retention rates, overall trial design (specifically how well the protocol balanced scientific and practical considerations), willingness to be randomised, and data collection completion rates.

Intervention fidelity was assessed through the questions (1) ‘Can the intervention, as designed, be delivered to care staff and PwD in LTC?’ (delivery); and (2) ‘Did the LTC facilities, care staff, and PwD in LTC receive the intervention as intended?’ (receipt).

For Level 1, the intervention implementation process was tracked, including the time taken to access hearing and vision assessments, receipt and uptake of sensory aids, and adherence to the PSP (data available on request).

For Level 2, records were kept on training sessions with care staff and sensory champions, noting the date, duration, location, attendance, and staff designations. Additional records included planned and ad hoc staff contact (implementation enhancement) and reviews of sensory champions’ actions regarding PwD in LTC sensory health at each follow-up to assess adherence to the protocol.

For Level 3, changes made to the sensory environment were documented from the week after sensory champion training until the follow-up visit. Lastly, for Level 4, existing care provision was mapped across LTC facilities and community-based hearing and vision care providers.

Adherence to sensory devices was tracked as part of intervention fidelity. In the present trial, adherence was recorded through weekly reports from the sensory champions noting if residents were generally wearing their devices.

Tolerability, as an aspect of ‘acceptability’, was defined as the ability to endure the intervention, which was assessed by recording the number of SAEs related to the intervention or non-adherence to the recommended sensory aids63.

Care as usual (CAU)

CAU was defined as the standard care provided within the setting and was maintained in both arms of the study. Participants in the CAU group received no additional intervention. Since little is known about the specifics of usual care for vision, hearing, or the sensory environment in long-term care (LTC) facilities, a survey was conducted with LTC managers and DONs to identify the key components of CAU related to sensory and cognitive health for PwD in LTC in Ireland. Separate ethical approval for this survey was obtained from the Social Research Ethics Committee (School of Clinical Therapies Subcommittee) at University College Cork (23 November 2022; ref. CT-SREC-2022-2023 (33)) and is reported below.

Demographic and clinical data

Demographic and clinical data were collected through face-to-face interviews during screening and baseline assessments, with follow-up data collected approximately 3 months post-randomisation (see supplementary material 4). PwD in LTC data were gathered through proxy reports from a designated staff informant (DSI)—a staff member within the facility who was familiar with the resident and could provide an accurate report. Each DSI received training in data collection. Data for potential efficacy outcome measures (see supplementary material 5) were collected at multiple levels and time points throughout the intervention. This structured, multi-level approach aimed to capture a comprehensive picture of the intervention’s potential effects on individuals, staff, and the facility environment.

Staff data

Sensory champions and general staff members in both arms completed the knowledge, attitudes, and practice (KAP) questionnaire at baseline and follow-up. It evaluates awareness of sensory impairments, confidence in handling sensory tools, and staff perceptions of the importance of sensory care. Sensory champions and general staff in the intervention arm also completed the TARS, which assesses their opinions on the acceptability, effectiveness, and impact of the sensory support training provided by the research therapist.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the suitability for the definitive trial. Missingness of data, variability (SD) of the outcomes (baseline and 3 months) and point estimates, and difference in outcomes at 3 months in each arm were calculated overall and by arm. To fully explore the feasibility of cost-effectiveness analysis, exploratory analysis estimated Quality-Adjusted Life Years (from participants’ responses to EQ-5D-5L) and total cost (from responses to resource tools).

Data availability

The data and materials supporting this article are available in the Open Science Framework repository: Sense-Cog Residential Care [https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/KDNZM].

References

Begley, E., Gibb, M., Kelly, G., Keogh, F. & Timmons, S. Model of Care for Dementia in Ireland. Tullamore: National Dementia Services (2023).

Lin, F. R. et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 293–299 (2013).

Bowen, M. et al. The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in People with Dementia (the PrOVIDe Study): A Cross-Sectional Study of People Aged 60–89 Years with Dementia and Qualitative Exploration of Individual, Carer and Professional Perspectives (NIHR Journals Library, 2016).

Connelly, J. et al. SENSE-Cog Residential Care: hearing and vision support for residents with dementia in long-term care in Ireland: protocol for a pilot cluster randomised controlled trial. https://www.researchsquare.com, 10.21203/rs.3.rs-2984621/v1 (2023).

Lin, F. R. & Albert, M. Hearing loss and dementia—who is listening?. Aging Ment. Health 18, 671–673 (2014).

Nagarajan, N. et al. Vision impairment and cognitive decline among older adults: a systematic review. BMJ Open 12, e047929 (2022).

Guthrie, D. M. et al. Combined impairments in vision, hearing and cognition are associated with greater levels of functional and communication difficulties than cognitive impairment alone: analysis of interRAI data for home care and long-term care recipients in Ontario. PLoS ONE 13, e0192971 (2018).

Sloane, P. D., Whitson, H. & Williams, S. W. Addressing hearing and vision impairment in long-term care: an important and often-neglected care priority. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 22, 1151–1155 (2021).

Rogers, M. A. M. & Langa, K. M. Untreated poor vision: a contributing factor to late-life dementia. Am. J. Epidemiol. 171, 728–735 (2010).

Xiao, Z. et al. Sensory impairments and cognitive decline in older adults: a review from a population-based perspective. Aging Health Res. 1, 100002 (2021).

Hubbard, H. I., Mamo, S. K. & Hopper, T. Dementia and hearing loss: interrelationships and treatment considerations. Semin. Speech Lang. 39, 197–210 (2018).

Pryce, H. & Gooberman-Hill, R. There’s a hell of a noise’: living with a hearing loss in residential care. Age Ageing 41, 40–46 (2012).

Cross, H., Armitage, C. J., Dawes, P., Leroi, I. & Millman, R. E. Improving the provision of hearing care to long-term care home residents with dementia: developing a behaviour change intervention for care staff. J. Long-Term Care, 122–138 (2024).

Andrusjak, W., Barbosa, A. & Mountain, G. Hearing and vision care provided to older people residing in care homes: a cross-sectional survey of care home staff. BMC Geriatr. 21, 32 (2021).

Cohen-Mansfield, J. & Infeld, D. L. Hearing aids for nursing home residents: current policy and future needs. Health Policy 79, 49–56 (2006).

Cohen-Mansfield, J. & Taylor, J. W. Hearing aid use in nursing homes, part 2: barriers to effective utilization of hearing aids. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 5, 289–296 (2004).

Solheim, J., Shiryaeva, O. & Kvaerner, K. J. Lack of ear care knowledge in nursing homes. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 9, 481–488 (2016).

Aldridge, Z. & Newsome, S. Dementia and sensory impairment. J. Community Nurs. 36, 56–61 (2022).

Leroi, I. et al. Sensory health for residents with dementia in care homes in england: a knowledge, attitudes, and practice survey. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 22, 1518–1524.e12 (2021).

Cross, H. et al. Effectiveness of hearing rehabilitation for care home residents with dementia: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 23, 450–460.e4 (2022).

Leroi, I. et al. Hearing and vision impairment in people with dementia: a guide for clinicians. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 101, 1667–1670 (2020).

Littlejohn, J. et al. International practice recommendations for the recognition and management of hearing and vision impairment in people with dementia. Gerontology 68, 121–135 (2022).

Leroi, I. et al. Hearing and vision rehabilitation for people with dementia in five European countries (SENSE-Cog): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. 100625, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanhl.2024.07.008 (2024).

Regan, J. et al. Individualised sensory intervention to improve quality of life in people with dementia and their companions (SENSE-Cog trial): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 20, 80 (2019).

Olsen, C. et al. Differences in quality of life in home-dwelling persons and nursing home residents with dementia – a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 16, 137 (2016).

Weisman, G., Chaudhury, H. & Moore, K. Theory and practice of place: toward an integrative model. in The Many Dimensions of Aging: Essays in Honor of M. Powell Lawton, 3–21 (Springer, 2000).

Skivington, K. et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 374, n2061 (2021).

Muller, N., Condon, A., Stanley, S. & Connelly, J. P. Care as usual for vision and hearing impairment for residents with dementia in Irish nursing homes. Int. Conf. Commun. Med. Ethics. Poster presentation. (2023).

Graham, L. et al. PATCH: posture and mobility training for care staff versus usual care in care homes: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 19, 521 (2018).

How long does it take to get used to hearing aids? The Hearing Solution https://www.thehearingsolution.com/hearing-blog/how-long-does-it-take-to-get-used-to-hearing-aids.

Is it hard to adjust to wearing hearing aids? Starkey https://www.starkey.co.uk (2025).

Farrell, B., Kenyon, S. & Shakur, H. Managing clinical trials. Trials 11, 78 (2010).

Zweben, A., Fucito, L. M. & O’Malley, S. S. Effective strategies for maintaining research participation in clinical trials. Drug Inf. J. 43, https://doi.org/10.1177/009286150904300411 (2009).

Gibbons, L., Mccurry, S. & Teri, L. Quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease: patient and caregiver reports. J. Ment. Health Aging 5, 21–32 (1999).

Smith, S. C. et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life for people with dementia: development of a new instrument (DEMQOL) and an evaluation of current methodology. Health Technol. Assess. Winch. Engl. 9, 1–93 (2005).

Cummings, J., Morstorf, T. & Lee, G. Alzheimer’s drug-development pipeline: 2016. Alzheimers Dement. 2, 222–232 (2016).

Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D. & CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 340, c332 (2010).

Adrait, A. et al. Do hearing aids influence behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and quality of life in hearing impaired alzheimer’s disease patients and their caregivers?. J. Alzheimers Dis. 58, 109–121 (2017).

Nguyen, Q. D. et al. Systematic review of research barriers, facilitators, and stakeholders in long-term care and geriatric settings, and a conceptual mapping framework to build research capacity. BMC Geriatr. 23, 622 (2023).

Hooper, E. et al. Feasibility of an intervention to support hearing and vision in dementia: the SENSE-Cog field trial. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 67, 1472–1477 (2019).

Hooper, E. et al. Enablers and barriers to hearing aid use in people living with dementia. J. Appl. Gerontol. 43, 978–989 (2024).

Walsh, B., Connolly, S., Wren, M.-A. & Hill, L. Supporting sustainable long-term residential care in Ireland: a study protocol for the Sustainable Residential Care (SRC) project. HRB Open Res. 5, 30 (2022).

Huang, G. D. et al. Clinical trials recruitment planning: a proposed framework from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative. Contemp. Clin. Trials 66, 74–79 (2018).

Leroi, I. & Miller, A.-M. Process trumps research: a root cause analysis of delays in conducting care home research in Ireland. In 7th International Clinical Trial Methodology Conference poster presentation (Edinburgh, 2024).

Collins, L. M., Murphy, S. A. & Strecher, V. The multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) and the sequential multiple assignment randomized trial (SMART): new methods for more potent ehealth interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 32, S112–S118 (2007).

Health Information and Quality Authority. Overview Report Monitoring And Regulation Of Older Persons Services In 2022. https://www.hiqa.ie/sites/default/files/2023-12/HIQA-Overview-Report-Monitoring-Regulation-Older-Persons-Services-2022.pdf (2023).

Cahill, S., O’Nolan, C., O’Caheny, D. & Bobersky, A. An Irish national survey of dementia in long-term residential care. 54 (2014).

Katzman, R. et al. Validation of a short orientation-memory-concentration test of cognitive impairment. Am. J. Psychiatry 140, 734–739 (1983).

Reisberg, B. Functional assessment staging (FAST). Psychopharmacol. Bull. 24, 653–659 (1988).

Reisberg, B., Ferris, S. H., de Leon, M. J. & Crook, T. The Global Deterioration Scale for assessment of primary degenerative dementia. Am. J. Psychiatry 139, 1136–1139 (1982).

Mendiratta, P., Schoo, C. & Latif, R. Clinical Frailty Scale (StatPearls Publishing, 2025).

Salvi, F. et al. A manual of guidelines to score the modified cumulative illness rating scale and its validation in acute hospitalized elderly patients. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 56, 1926–1931 (2008).

Wood, S. et al. The use of the neuropsychiatric inventory in nursing home residents. Characterization and measurement. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 8, 75–83 (2000).

Ventry, I. M. & Weinstein, B. E. The hearing handicap inventory for the elderly: a new tool. Ear Hear. 3, 128–134 (1982).

Stelmack, J. A. et al. Measuring outcomes of vision rehabilitation with the Veterans Affairs Low Vision Visual Functioning Questionnaire. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 47, 3253–3261 (2006).

Whitehead, S. J. & Ali, S. Health outcomes in economic evaluation: the QALY and utilities. Br. Med. Bull. 96, 5–21 (2010).

Stoner, C. R., Orrell, M. & Spector, A. Psychometric properties and factor analysis of the Engagement and Independence in Dementia Questionnaire (EID-Q). Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 46, 119–127 (2018).

Charlesworth, G., Burnell, K., Hoe, J., Orrell, M. & Russell, I. Acceptance checklist for clinical effectiveness pilot trials: a systematic approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 13, 1–7 (2013).

Thabane, L. et al. Methods and processes for development of a CONSORT extension for reporting pilot randomized controlled trials. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 2, 25 (2016).

Mellor, K., Albury, C., Dutton, S. J., Eldridge, S. & Hopewell, S. Recommendations for progression criteria during external randomised pilot trial design, conduct, analysis and reporting. Pilot Feasibility Stud. 9, 59 (2023).

Orsmond, G. I. & Cohn, E. S. The distinctive features of a feasibility study: objectives and guiding questions. OTJR 35, 169–177 (2015).

Stanniland, C. & Taylor, D. Tolerability of atypical antipsychotics. Drug Saf. 22, 195–214 (2000).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank discussion group expert advisors, members of the Dementia Research Advisory Team (DRAT) and the Alzheimer Society of Ireland (ASI). We would also like to thank Erin Boland, Alejandro Lopez Valdes, Ann-Michelle Mullally, Gerard O’Nolan, Sarah O’Sullivan, Daniel Regan, Deirdre Shanagher, Katy Tobin, and Helen Tormey. We also thank the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI), Trinity College Dublin (TCD), for supporting the study. Finally, we would also like to thank Professor Piers Dawes and his research group at University of Queensland, Australia for their advice and collaboration. We are also grateful for support from Trinity-St James’s Clinical Research Facility, The National Charity for Deafness and Hearing Loss (CHIME), Visioncall Ireland, National Council for the Blind of Ireland (NCBI), Dementia Services Information and Development Centre (DSiDC), Nursing Homes Ireland (NHI), Health Research Board – Clinical Trials Network (HRB-CTN), Dementia Trials Ireland (DTI).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The SENSE-Cog Residential Care Trial Development Team conceptualised and designed the field trial. IL is the programme lead and chief investigator and conceived and designed the study and led the manuscript development. R.N. was the study coordinator and assisted with writing the first draft of the manuscript. J.P.C. is the Research Therapist and contributed to intervention and protocol development and reviewed, edited, and organised the final version of the manuscript. P.G., J.C., and V.R.R. are research assistants and contributed to the development of the manuscript. A.E.R. is an audiologist and assisted with study development. M.G. is a multi-disciplinary academic and assisted with study development. L.G. is a Senior Research Fellow at the Academic Unit for Ageing and Stroke Research, Bradford, UK, and assisted with intervention development. N.M. is a Professor of Speech and Hearing Sciences and assisted with study development. N.C. provided vision services and supported intervention development. B.L. provided audiological services. B.B., J.N.P., and H.R.B. are members of the Sense-Cog Residential Care Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) panel and advised the research team on intervention development, trial design and data analysis. C.O.R. supported the PPI panel to meaningfully contribute to the trial. DT is an Assistant Professor of Economics and provided health economic input and assisted in manuscript development and analysis of outcome data. M.A. and A.Y. are PhD students in health economics and supported D.T. in the construction of a health economic model. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the article and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Leroi, I., Aijala, M., Boland, E. et al. SENSE-Cog Residential Care: piloting hearing and vision support for dementia in long-term care. npj Dement. 2, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44400-025-00046-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44400-025-00046-8