Abstract

Perovskite materials have received a lot of attention due to their distinctive structural, electronic, and optical characteristics, particularly in photocatalytic water splitting applications. This work aims to explore structural, electronic, optical, elastic, and mechanical properties of cubic-phase A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) double perovskites using DFT within the GGA-PBE framework. All compounds exhibit negative formation energies (−1.45, −1.14, and −1.07 eV) along with the tolerance factors ranging from 0.820 to 0.896, which fall within the perovskite stability domain. In the phonon dispersion analysis of all compounds, no imaginary frequencies appeared, confirming their dynamic stability. The materials possess a bandgap 1.891–2.014 eV (GGA-PBE) and 1.896–2.038 eV (YS-PBE0), appropriate for visible light absorption, with band gap energies increasing systematically with A-site ionic radius (Na < K < Rb). Dielectric function analysis reveals stable dispersion across the visible spectrum, with static dielectric constants ranging from 3.9 to 4.7, indicating a high degree of polarizability. Mechanical assessments, including positive shear modulus (G) values and Pugh’s ratio (B/G > 1.75), confirm their ductile and stable nature. This work lays the groundwork for designing cost-effective photocatalytic materials for hydrogen evolution reaction (HER).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The accelerating worldwide energy consumption, exacerbated by the gradual depletion of limited fossil-based energy reserves, emphasizes an immediate necessity to adopt sustainable and carbon-neutral energy alternatives. Currently, non-renewable energy sources account for approximately 90% of global energy needs, with the majority of this energy being utilized in the industrial and transportation sectors1. Nevertheless, the sustained use of these substances is becoming progressively untenable due to environmental degradation, climate change, and resource scarcity. Consequently, the necessity to decarbonize global energy systems has generated considerable interest in renewable energy technologies. Hydropower, wind, and geothermal energy have each demonstrated potential for generating clean energy2,3. However, their deployment is constrained by site-specific availability, intermittency, and integration challenges4. Conversely, solar energy offers a universally accessible and effectively inexhaustible resource. According to theoretical estimates, harnessing just 0.01% of the solar irradiance reaching Earth could potentially meet global energy demand5,6,7.

Nevertheless, despite significant advances in photovoltaic materials and device architectures, limitations in efficiency, energy storage, and scalability continue to impede widespread adoption8. To address these limitations, the utilization of hydrogen energy, particularly when produced via solar-driven or photoelectrochemical water splitting, has proven to be a compelling alternative9. Due to its high-energy-density, carbon-free emission, hydrogen is a promising option for long-term energy storage and integration with intermittent renewable resources, developing a framework for long-term resilience and sustainability in the energy sector10. Hydrogen has emerged as a versatile, storable, and carbon-free energy carrier, possessing considerable potential to streamline the global transformation of energy infrastructure towards sustainability. A salient benefit of this approach is absolute reliance on no fossil fuels, a factor that positions it as a feasible strategy for achieving deep decarbonization. In the context of combustion engines or fuel cells, hydrogen reacts with oxygen, yielding water as the sole product. This process generates significant thermal or electrical energy with no concomitant release of CO2, NOx, or other pollutants. Hydrogen offers several operational advantages in addition to its environmental benefits, including geographic flexibility, compact system design, benign reaction products, and compatibility with both centralized and distributed energy systems. These characteristics render hydrogen a desirable component in future clean energy portfolios. Consequently, global research endeavors are currently being augmented to formulate effective, scalable, and sustainable hydrogen production pathways, with a particular emphasis on solar and catalytic water-splitting technologies.

As indicated in the existing literature, hydrogen can be produced using various technological approaches, including thermochemical reforming, photobiological conversion, high-temperature electrolysis, photoelectrochemical water splitting, and photocatalytic methods11. Among those above, solar-driven hydrogen, particularly via photocatalytic water splitting, is gaining widespread recognition for its capability to deliver clean, large-scale, and sustainable hydrogen production. To function efficiently, photocatalysts must fulfill various critical standards12. Initially, materials must demonstrate a robust capacity for absorbing solar radiation, thereby facilitating effective creation of electron-hole pairs. Secondly, the locations of conduction bands (CB) and valence bands (VB) with the redox potential are imperative. This enables thermodynamically favorable evolution of H2 and O2. In conclusion, photocatalysts must facilitate rapid charge carrier dynamics to reduce the charge recombination rate and maximize quantum yield. These requirements have guided the design of advanced semiconductor systems, including those based on perovskite and titanate materials, with enhanced stability, light-harvesting ability, and catalytic performance.

Perovskites are a structurally and chemically diverse family of materials with exceptional potential for various practical applications, including photocatalysis, photovoltaics, and energy storage13,14,15. In the current decade, perovskite-based systems have gained significant recognition for their potential applications in catalytic water splitting, particularly under visible-spectrum illumination. This attention is primarily credited to their tunable band structures, efficient charge carrier dynamics, and strong light-harvesting capabilities. A specific subclass within the perovskite family is double perovskite, typically represented using the formula A2BB′X6, where A is a monovalent cation (commonly an alkali metal), B and B′ are two different metal cations, and X corresponds to a halide anion. The compositional diversity inherent in this structure offers a rich platform for tailoring properties to meet the demands of specific functional applications. The structural versatility of this material allows for precise control over its lattice parameters, electronic properties, and photocatalytic activity. These characteristics render perovskites a promising platform for designing advanced functional materials for solar-driven hydrogen evolution and other energy conversion applications16. Bi3+ cations provide a non-toxic and environmentally benign alternative to Pb2+ in halide perovskites, directly addressing the toxicity concerns associated with Pb-based photocatalysts17. Incorporation of Li+ at the B-site strengthens lattice stability through strong ionic bonding with the halide octahedra, while the presence of larger alkali cations (Na+, K+, Rb+) at the A-site stabilizes the Fm3̅m double-perovskite framework by filling the cuboctahedral cavities and preserving cubic symmetry18. Bi-based halide double perovskites are further distinguished by defect-tolerant electronic structures and band gaps within the visible range; for instance, alloying in Cs2AgBiBr6 has been shown to reduce its band gap and generate long-lived charge carriers, reflecting high defect tolerance19. While compounds such as Cs2AgBiX6 and related Bi-based halides have been widely investigated, the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) family has remained virtually unexplored. The present work provides the first systematic investigation of their structural, elastic, electronic, and photocatalytic properties, thereby addressing this critical knowledge gap and establishing their potential as stable, lead-free materials for clean energy applications. Both experimental and theoretical approaches have demonstrated that Bi-based double perovskites, such as Cs2AgBiBr6 and Cs2NaBiCl6, exhibit excellent optoelectronic properties, long carrier lifetimes, and enhanced environmental stability20,21,22,23. Experimentally, Cs2AgBiBr6 possesses an indirect band gap of ~2.0 eV and strong defect tolerance, enabling efficient absorption in the visible spectrum22. On the theoretical side, high-throughput screening and first-principles calculations have elucidated structural stability and defect chemistry of numerous Bi-based perovskites, further confirming their potential as lead-free candidates for energy applications24. Beyond photovoltaics, halide double perovskites are increasingly being explored for photocatalytic water splitting25.

Despite advances in halide double perovskites, the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) family remains largely unexplored. The choice of A-site cation plays a pivotal role in tuning structural stability, lattice parameters, and overall electronic properties of these materials. Incorporation of Li+ at the B-site reinforces structural robustness through strong ionic interactions, while the Bi3+-I- framework enables visible-light absorption and defect-tolerant band edges. Systematic exploration of A2LiBiI6 perovskites with different A-site cations, therefore, can provide an opportunity to identify stable, non-toxic photocatalysts optimized for solar-driven water splitting and other renewable energy applications. This study examines the potential of the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) double perovskite family toward photocatalytic water splitting, focusing on its structural, electronic, optical, elastic, and mechanical properties. A detailed analysis of material properties was performed using density functional theory (DFT) with the GGA-PBE functional, as implemented in the CASTEP simulation environment. The electronic properties were investigated through evaluations, including total and partial density of states (DOS) and band structure. Following structural optimization, an in-depth analysis of optical characteristics was conducted to determine their light-harvesting potential. Several mechanical properties were determined, including elastic constants, bulk and shear moduli, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio, to ensure a comprehensive assessment of their mechanical stability and ductile-brittle behavior. Based on the combined analysis, a predictive framework can be established to understand the multifunctional behavior of A2LiBiI6 perovskites, demonstrating their potential for applications in renewable energy, particularly in the production of hydrogen using solar energy.

Results and discussion

Structural stability

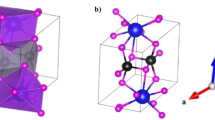

The analysis of a crystalline material’s crystal lattice is imperative for comprehending its crystal symmetry, lattice parameters, space group, stability, and other fundamental characteristics. The accuracy of structural information is critical to the development of subsequent computational investigations26. In this study, A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskites in the cubical phase (Fm3m, #225) were optimized. At the start of the geometry optimization iteration process, the following Wykoff positions were considered: A-site atoms (Na/K/Rb) positioned at 8c (0.25, 0.25, 0.75), Li-atoms positioned at 4b (0.5, 0.00, 0.00), Bi-atoms positioned at 4a (0.00, 0.00, 0.00), and I-atoms positioned at 24e (0.254653, 0.00, 0.00)27. As a result of volume optimization, both crystal structures were fully relaxed, allowing determination of their equilibrium geometries and corresponding minimum ground-state energies. The optimized crystal units for each composition are depicted in Fig. 1.

Across the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na→K→Rb) perovskite series, the lattice expands systematically with the substitution of progressively larger alkali-metal cations at the A-site. The lattice constants (a = b = c) increase from 11.997 Å (Na) to 12.189 Å (Rb), with the unit cell volume correspondingly rising from 1726.921 Å3 to 1811.180 Å3. Systematic volumetric growth is a result of the A-site cation’s steric influence, which exerts an expansive chemical pressure on the crystal lattice. A significant aspect of the series is that cubic symmetry is preserved throughout, highlighting the structural robustness of the double perovskite framework, despite the substantial mismatch in ionic size. With such tunable lattice dimensions, electronic bandwidth and structural tolerance can be engineered without compromising phase stability.

The Goldschmidt’s tolerance factor (\({{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{G}}}\)) and octahedral factor (μ), both are pivotal parameters in representing the stability of a compound in the perovskite structural frame28. The following relations, Eqs. 1–2, are utilized to facilitate calculation:

In the case of A2LiBiI6 compounds, an increase in the tolerance factor is observed with larger A-site cations. The tolerance factor and octahedral factor were calculated using Shannon’s ionic radii29, with values of Na+ (1.39 Å), K+ (1.64 Å), Rb+ (1.72 Å), Li+ (0.76 Å), Bi3+ (1.03 Å), and I- (2.20 Å), respectively. The compounds in this study, namely Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6, exhibited \({{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{G}}}\) of 0.820, 0.877, and 0.896, respectively. A \({{\rm{\tau }}}_{{\rm{G}}}\) approaching one generally signifies a more optimal and symmetrical perovskite cubic structure. Consequently, all the designed compounds possess a tolerance factor of approximately 1, indicating stability within the cubic perovskite framework; however, slight distortions may still occur.

It is imperative to note that the octahedral factor (μ), signifying the proportion between B-site cation radius and X-site radius, functions as a pivotal parameter that exerts a distinct influence on stability and distortion of the octahedra within perovskite structures. For adequate photocatalytic water splitting, stable and well-connected octahedra are essential for efficient charge separation and transport. For the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) series, all compounds exhibit the same octahedral factor values (0.407).

The enthalpy of formation for A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskite is represented by Eq. 3.

The enthalpy of formation is a critical parameter of a material’s thermodynamic stabilization, with more negative values indicating greater stability. In the context of photocatalytic water splitting, thermodynamic stability is essential to prevent decomposition under light and aqueous conditions. Among the A2LiBiI6 compounds, Na2LiBiI6 exhibits the most negative enthalpy of formation (−1.45 eV/formula unit), followed by K2LiBiI6 (−1.14 eV/formula unit) and Rb2LiBiI6 (−1.07 eV/formula unit). This trend suggests that Na2LiBiI6 is the most stable phase, making it more resistant to degradation during prolonged exposure to water and light. Therefore, its higher thermodynamic stability makes Na2LiBiI6 a more promising candidate for durable water-splitting applications compared to the K and Rb analogues, as presented in Table 1.

Electronic properties

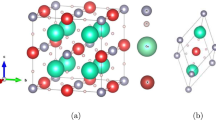

The intricate electronic landscape of a material reveals the quantum mechanical basis of its functional behavior, providing a compass to guide the development of next-generation energy technologies. In this context, electronic band structure, and density of states (DOS) provide crucial insight into charge carrier mobility, the band gap characteristics, and energy absorption and conversion capabilities. Through DFT calculations, we reveal the fundamental electronic features of the proposed perovskite compounds, thereby gaining a deeper understanding of how atomic-scale interactions govern macroscopic properties relevant to optoelectronic and clean energy applications30. The electronic structures of the A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) compounds were systematically investigated using firstly band structure and then DOS and PDOS analysis, adopting the methodology described in Section 2. The computed band structures reveal that all three compounds exhibit indirect band gaps (G→R) in the first Brillouin zone. It prevents electrons from passing directly (without a phonon) from the VB to the CB (lattice vibration) to conserve momentum. Developing indirect band gaps stems from the interplay between lattice symmetry, orbital hybridization, and relativistic effects, illustrating the complex quantum dynamics that govern halide-based perovskites31. Figure 2a–c illustrates computed band structure dispersion and corresponding DOS of Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6. Band gap of Na2LiBiI6 is 1.891 eV, K2LiBiI6 is 1.989 eV, whereas Rb2LiBiI6 is 2.014 eV.

To further validate these findings, hybrid functional YS-PBE032 calculations were performed, as shown in the right-side panels of Fig. 2. The corrected band gap values increased to 1.906 eV for Na2LiBiI6, 2.004 eV for K2LiBiI6, and 2.038 eV for Rb2LiBiI6, confirming the semiconducting nature of all three compounds. The modest upshift in band gaps relative to GGA-PBE underscores the improved treatment of electronic exchange–correlation effects within hybrid functionals, offering a more realistic estimate for optoelectronic applications. Notably, the corrected values remain well-positioned within the visible light regime, reinforcing their suitability for solar-driven photocatalysis and water splitting.

As a result, all three compounds are semiconducting materials with indirect band gaps in the visible range, rendering them conductive to applications in photocatalysis and optoelectronics. These values situate the materials within the visible light spectrum, which is critical for efficient solar energy harvesting33. The indirect bandgap character may contribute to reduced radiative recombination rates, potentially enhancing carrier lifetimes and charge separation, which are essential factors for photocatalytic applications. These bandgap values fall within the optimal range of 1.6–2.2 eV for visible-light-driven photocatalysis, striking a balance between sufficient redox driving force and photon absorption efficiency34. The band gaps of these materials exceed the thermodynamic minimum energy requirement of 1.23 eV for water splitting, thereby providing room to overcome overpotentials in practical applications. Together, the combination of suitable bandgap magnitude, indirect bandgap nature, and favorable band dispersion highlights the promise of A2LiBiI6 compounds as photocatalysts, particularly for hydrogen production from water splitting, when driven by solar energy.

In the calculated band structure, a well-defined indirect band gap is evident, indicating momentum-dependent charge carrier transitions that require phonon assistance. While the band dispersion outlines the relation between energy and momentum, it does not provide a complete understanding of the orbital contributions that determine these electronic states. This gap can be bridged by the DOS, which calculates possible states at each energy level, thereby deciphering the electronic fingerprint of the system. Both total and partial DOS provide evidence of the existence of a band gap and illuminate the specific atomic and orbital constituents that make up the VB and CB34.

PDOS of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskites are presented in Fig. 3a–c, respectively. These figures indicate the influence of sodium, potassium, and rubidium on the A-site of the crystal structure. Figure 3a demonstrates that VBM of Na2LiBiI6 consists primarily of iodine 5p orbitals, with minor contributions from Bi-6p and I-5s states. CBM is chiefly derived from Bi-6p and I-5p orbitals. In the case of K2LiBiI6 (Fig. 3b), VBM is similarly dominated by I-5p states, accompanied by hybridized contributions from I-5s and Bi-5p orbitals. CBM is primarily influenced by Bi-6p and I-5p states, with a comparatively minor contribution from I-5s character in the higher conduction region. For Rb2LiBiI6 (Fig. 3c), the VBM primarily rises from I-5p and Bi-6p states, with secondary contributions from I-5s and Bi-6s orbitals. The CBM, as observed in the other compounds, is mainly governed by Bi-6p and I-5p states. Orbital states around the Fermi level influence a significant part of the optical response, since these states support electron excitation from VB to CB when photons are interacted with them.

Dynamical stability

A phonon analysis is imperative for assessing dynamical stability and understanding the lattice dynamics of materials, which significantly affect their thermal, mechanical, and transport properties35. Dynamic stability is pivotal for the real-world application of photocatalyst materials as they enable them to undergo multiple cycles without losing efficiency or functionality. As well as providing insight into the vibrational stability of materials, phonon dispersion band plots are also helpful in determining the lattice vibrational characteristics of materials36. An analysis of phonon dispersion was conducted on Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6 materials to determine their vibrational characteristics. A2LiBiI6 (A= Na, K, Rb) phonon dispersion graphs are displayed in Fig. 4a–c in Brillouin zone symmetry-defined directions. A lack of evidence of imaginary phonon frequencies in the Brillouin zone of all three compounds, which confirms their dynamic stability36,37. A comparison of Na2LiBiI6 and Rb2LiBiI6 reveals a similar maximum phonon frequency of approximately ~8 THz, while K2LiBiI6 displays a slightly lower phonon frequency ceiling of approximately ~6 THz. In all compounds, flat optical branches indicate low phonon group velocities, which may result in low thermal conductivity at the lattice, which is a desirable property for thermoelectric materials38. As well, the distinct separation between the acoustic and optical branches, particularly in K2LiBiI6, indicates differences in vibrational behavior that may affect phonon scattering mechanisms. As a result of these phonon spectra, we have developed important insights into the lattice dynamics and potential functional applications of these halide double perovskites. To complement the dispersion curves, the phonon density of states (PhDOS) was also evaluated, as shown in the right-hand panels of Fig. 4. The Phonon DOS spectra reveal that Na2LiBiI6 exhibits a relatively broad vibrational distribution with dominant modes below 6 THz, while K2LiBiI6 displays sharper peaks concentrated below 5 THz, consistent with its lower phonon cutoff. Rb2LiBiI6, in contrast, shows a wider spread of vibrational modes with distinct peaks extending toward 6 THz, highlighting stronger lattice interactions.

These Phonon DOS features corroborate the phonon dispersion trends and provide additional insight into vibrational contributions to thermal transport. In particular, the concentration of low-frequency modes suggests pronounced acoustic phonon activity, which is likely to enhance phonon–phonon scattering and further suppress lattice thermal conductivity. This vibrational landscape underlines the potential of A2LiBiI6 halide double perovskites for thermoelectric and optoelectronic applications, where controlled phonon transport is crucial.

Optical characteristics

When assessing the applicability of a substance for optoelectronic and other applications, its optical behavior is of vital importance, as it governs its interaction with electromagnetic radiation. To assess the potential of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) double perovskites for specifically solar-assisted water splitting applications, we computed their key optical parameters, like dielectric function, absorption, reflectivity, refractive index, conductivity, and loss function. These optical key parameters were obtained using the GGA-PBE approximation.

The dielectric function is a fundamental parameter for understanding and designing optical and electronic devices39. According to the Ehrenreich-Cohen formalism40, optical response of a material is determined by its complex dielectric function (Eq. 4).

Where \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) and ɛ2 (ω) represent real part and imaginary part of dielectric function. For A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskites, \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\) was directly calculated, while \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) was derived using Kramer-Kronig relation. The electronic band structure of a crystal fundamentally determines optical properties and dielectric response.

ɛ1(ω) describes material’s ability to store electric energy and is directly related to polarization phenomena41. As illustrated in Fig. 5a, \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) exhibit significant optical activity across the UV-visible spectrum. The calculated static dielectric constants are \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(0\right)\,\) \(\approx 1.0\) for Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6. From Fig. 5a, the peak values of the real part in the visible region are \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) ≈5.5 for Na2LiBiI6, ≈5.4 for K2LiBiI6, and ≈5.3 for Rb2LiBiI6 (around~520–560 nm). All compounds exhibit a similar dispersion profile, characterized by positive values across most of the visible range, which confirms their dielectric stability and polarizability. However, Rb2LiBiI6 displays a slightly higher \({\varepsilon }_{1}\left(\omega \right)\) magnitude in the longer wavelength region, indicative of stronger polarization effects. This phenomenon is presumably attributable to the augmented ionic radius of Rb+, which results in a modest alteration of the lattice polarizability.

Further insight into the optical absorption behavior of A2LiBiI6 (A=Na, K, Rb) perovskites is provided by \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\)41. As shown in Fig. 5a, \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\) exhibits strong peaks in the wavelength region of ~300,600 nm, reflecting significant optical transitions within the UV-visible spectrum. The dominant peaks in ε2 between 400 and 600 nm suggest strong absorption, which facilitates the electron-hole pairs creation that are important for redox reactions in water splitting phenomena39. Furthermore, the peak intensity of \({\varepsilon }_{2}\left(\omega \right)\) is highest for Rb2LiBiI6, highlighting its superior photon absorption capacity in the visible range. This behavior underscores Rb2LiBiI6’s greater feasible for optoelectronic and photocatalytic applications, predominantly in visible-light-driven processes.

The optical absorption coefficient, \(\alpha \left(\omega \right)\) describes the lessening of light intensity per unit distance as it spreads through a material, providing a quantitative measure of how rapidly the intensity diminishes with thickness42. It can be derived from the dielectric function using Eq. 5.

The absorption coefficient, depicted in Fig. 5b, shows that absorption spectra of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskites exhibit a sharp absorption edge in the ultraviolet (UV) region, with a pronounced rise beginning near ~250–80 nm, corresponding to strong interband transitions from the hybridized I(5p) and Bi(6 s) states in VB to the Bi(6p)-dominated CB. This intense absorption in the UV range indicates efficient photon-matter interactions, enabling the creation of electron-hole pairs necessary for photocatalysis. Beyond the UV region, the absorption gradually decreases but maintains a broad tail extending into the visible range (~400–700 nm), with nearly overlapping behavior for Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6. Activity under visible light is especially advantageous for solar-driven water splitting, as it enables capture of a broader range of the solar spectrum. In photocatalytic water splitting, a high absorption coefficient is essential because it promotes the efficient production of a large number of photogenerated charge carriers. Photogenerated electrons in the conduction band can reduce protons (H+) to hydrogen (H2), while VB holes oxidize water molecules (H2O) to oxygen (O2). The efficient overlap of the absorption range with the solar spectrum, combined with strong absorption intensities, positions these A2LiBiI6 perovskites, particularly Rb2LiBiI6, as promising candidates for visible-light-assisted water splitting applications42.

In the reflectivity spectra’s (infrared to visible) region, calculated using the relation (Eq. 6).

The calculated spectra exhibit a pronounced ultraviolet peak at ~200 nm with maximum reflectivity of 0.92 (Na2LiBiI6), 0.93 (K2LiBiI6) and 0.94 (Rb2LiBiI6). Beyond ~250 nm, the reflectivity drops sharply; by 300 nm, it is ~ 0.20 and continues to decay to ~ 0.15–0.18 across the visible range (400–700 nm). This behavior indicates a strong interband transition in the deep-UV and a low, nearly flat reflectance in the visible, consistent with the onset of absorption near the band edge, as shown in Fig. 5c42. Due to its low overall reflectivity, A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskites may be beneficial as an anti-reflective coating or a transparent electrode for UV–Vis devices.

In order to explain plasmonic behavior, the energy loss function describes how electrons interact with the material and is determined by Eq. 743.

All studied compounds exhibit a pronounced energy-loss peak near 180 nm, corresponding to a plasmon energy of approximately 6.9 eV (Fig. 5d). This energy loss peak is associated with bulk plasmonic oscillations, signifying the transition from a dielectric to a metallic-like optical response. Such plasmon resonances are consistent with reported values for halide perovskites44. Such behavior is crucial in electron energy loss spectroscopy and in the fabrication of plasmonic devices.

The optical conductivity (\(\sigma =\frac{{\rm{\omega }}{\varepsilon }_{i}}{4\pi }\)) spectra of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) double perovskites exhibit distinct absorption onsets and prominent peaks within the visible region, indicating strong light-matter interaction crucial for optoelectronic and photocatalysis applications45. A steep rise in conductivity just above the bandgap (typically ~1.5–2.5 eV for halide perovskites) confirms efficient electronic transitions, facilitating electron-hole generation under solar illumination. Notably, the emergence of pronounced peaks in the mid-visible range reflects interband transitions, which are essential for harnessing solar photons effectively. These features indicate the material’s potential to support high carrier mobility and rapid charge separation, which are crucial for sustaining the water oxidation and proton reduction half-reactions. The sharp increase in σ(ω) suggests minimal recombination losses and supports the hypothesis of favorable excitonic dissociation. Taken together, the observed conductivity response under photon excitation substantiates the suitability of the investigated perovskite systems as visible-light-active photocatalysts, aligning with the thermodynamic and kinetic requirements for solar-driven water splitting.

Refractive index, (\(n({\rm{\omega }})=\frac{{\left[{[{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{1}\left(\omega \right)+{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{2}^{2}\left(\omega \right)]}^{1/2}+{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{1}\left(\omega \right)\right]}^{1/2}}{\sqrt{2}}\)), is a measure of how much light velocity is reduced in a medium as compared to its velocity in a vacuum46. The electromagnetic field interacts with the electrical charges in the material to modify the velocity of light. By measuring the extinction coefficient (\(k({\rm{\omega }})=\frac{{\left[{[{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{1}^{2}\left(\omega \right)+{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{2}^{2}\left(\omega \right)]}^{1/2}-{{\rm{\varepsilon }}}_{1}\left(\omega \right)\right]}^{1/2}}{\sqrt{2}}\)) of the material, we can determine the amount of attenuation the material causes to the incident electromagnetic wave due to absorption47. Dielectric functions associated with the optical refractive index (n) and extinction coefficient (k) are presented in Eq. 8a, b48.

The wavelength-dependent refractive indices of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb), as illustrated in Fig. 5f, reveal significant optical responses pertinent to solar-driven water splitting. The real part of the refractive index exceeds 2.0 across the visible spectrum (300–700 nm), indicating strong light confinement and potential for enhanced photon absorption. Simultaneously, the imaginary part exhibits prominent peaks in the UV region (200–350 nm), indicating efficient absorption that is critical for initiating photochemical reactions49. A red shift in the absorption onset from Na to Rb suggests a tunable band gap, attributable to the increasing ionic radii of A-site cations, which facilitates improved visible-light harvesting essential for efficient photocatalysis. Among the studied materials, Rb2LiBiI6 exhibits the highest refractive index, implying superior light-matter interaction and greater photocarrier generation39. Collectively, these optical properties position A2LiBiI6 compounds as promising candidates for visible-light-responsive photocatalysts in solar water splitting applications. These materials could be utilized for transparent window layers and UV-optical components in optoelectronic devices, making them an attractive option for optoelectronics and photovoltaics.

Elastic and mechanical responses

Elastic constants and derived mechanical moduli are indispensable for assessing structural robustness and mechanical behavior of halide perovskites under external stress50. Table 2 shows elastic constants C11, C12, and C44 computed for the cubic A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) perovskite in the framework of GGA-PBE51. These elastic constants provide insight into the resistance to various deformation modes, longitudinal (C11), lateral (C12), and shear (C44), and lay the basis to calculate key elastic and mechanical moduli.

All three perovskites, i.e., Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, Rb2LiBiI6, satisfy Born stability criteria for cubic systems52, specifically C11 > 0, C44 > 0, and C11-C12 > 0, confirming their mechanical stability. Among these compounds, K2LiBiI6 exhibits the highest elastic constants, suggesting superior mechanical rigidity compared to Na and Rb compounds. The calculated bulk modulus (B), shear modulus (G), and Young’s modulus (E) further support this trend, with K2LiBiI6 showing the highest values (B = 45.70 GPa, G = 7.68 GPa, E = 21.82 GPa), followed by Na2LiBiI6, and finally Rb2LiBiI6₆, which has the lowest moduli (B = 12.31 GPa, G = 7.24 GPa, E = 18.17 GPa). These parameters can be calculated by using Eq. 934. This trend reflects a systematic decrease in mechanical stiffness with an increasing ionic radius of A-site cation from K to Rb.

The Pugh ratio (B/G), a metric of ductile or brittle behavior, further delineates the mechanical characteristics53. Na2LiBiI6 and K2LiBiI6 exhibit exceptionally high B/G values (6.10 and 5.94, respectively), far exceeding the ductile threshold of 1.75. For Rb2LiBiI6, the calculated B/G ratio is 1.70, which lies above unity but below the widely accepted ductile threshold of 1.75. This places the compound at the brittle-ductile borderline. Hence, Rb2LiBiI6 is expected to show limited plastic deformability compared to Na2LiBiI6 and K2LiBiI6, which display much higher B/G ratios. Poisson’s ratio54 (\(\upsilon =\frac{3B-2G}{2(3B+G)})\), which reflects the degree of plasticity and interatomic bonding nature, remains nearly constant across the series (∼0.47), well above the critical value of 0.26, affirming the ductile nature of all three compositions55. To further evaluate the mechanical behavior, the Cauchy pressure (Cp= C12-C44) was calculated for each material. The results are 18.79 GPa (Na2LiBiI6), 32.12 GPa (K2LiBiI6), and 0.05 GPa (Rb2LiBiI6); all values are positive, indicating a predominance of metallic bonding and a ductile nature. Among them, the K2LiBiI6 material exhibits the highest Cauchy pressure, suggesting the greatest ductility. For Rb2LiBiI6, Cp = 0.05, which lies within the numerical accuracy of the DFT calculations and is effectively near zero.

The shear constant (\({{\rm{C}}}^{{\prime} }=\frac{C11-C12}{2}\)), positive values suggest that these materials are thermodynamically stable, with values ranging from 9.02 GPa (Rb2LiBiI6) to 10.66 GPa (K2LiBiI6).

The anisotropy factor (\(A=\frac{2{C}_{44}}{{C}_{11}-{C}_{12}}\)) serve as a crucial indicator of elastic anisotropy in cubic crystal systems56. For an elastically isotropic material, the ideal value of A is unity, while deviations from this value imply directional dependence in elastic properties. The calculated anisotropy factor for the studied materials is summarized in Table 2. For the first composition, Na2LiBiI6, A = 0.265, this significantly low value indicates a high degree of anisotropy, suggesting a lower resistance to shear deformation in specific crystallographic directions. For the other two compositions, anisotropy factors of 0.607 (K2LiBiI6) and 0.691 (Rb2LiBiI6) have been determined. These results indicate that anisotropy increases from the first to the third material, which may have implications for both its mechanical stability and potential applications where directional mechanical properties are crucial. This suggests that Rb2LiBiI6 may possess relatively better mechanical reliability under stress, while Na2LiBiI6, despite its higher ductility (B/G = 6.10), may suffer from directional instabilities. Among the studied compounds, K2LiBiI6 exhibits the most favorable mechanical properties for photocatalytic water splitting, as it combines high bulk modulus, high ductility (B/G = 5.94), and strong resistance to deformation, ensuring structural robustness under photocatalytic conditions. Na2LiBiI6, though ductile, shows pronounced anisotropy, while Rb2LiBiI6 is the weakest, making it the least suitable.

The anisotropic elastic properties of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) compounds were evaluated utilizing the ELATE software, providing insight into their directional mechanical responses. Figure 6 presents the variations in linear compressibility, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus, with green and blue indicating the maximum and minimum values, respectively. Nearly spherical surfaces correspond to isotropic behavior, whereas distortions indicate anisotropy. The results show that Poisson’s ratio, shear modulus, and Young’s modulus exhibit significant anisotropy, while linear compressibility remains nearly isotropic. Table 3 lists the corresponding maximum and minimum values of these parameters. Overall, the analysis confirms that A2LiBiI6 compounds possess anisotropic mechanical characteristics, reflecting an optimized crystal structure with strong bonding and uniform microstructural features. Such attributes enhance their potential for application in advanced photovoltaic and optoelectronic devices.

The anisotropic elastic properties of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) were evaluated using the ELATE software, providing insight into their directional mechanical responses. Figure 6 presents the variations in linear compressibility, Young’s modulus, Poisson’s ratio, and shear modulus, with green and blue indicating the maximum and minimum values, respectively57. Nearly spherical surfaces correspond to isotropic behavior, whereas distortions indicate anisotropy. The results show that Poisson’s ratio, shear modulus, and Young’s modulus exhibit significant anisotropy, while linear compressibility remains nearly isotropic. Table 3 lists the corresponding maximum and minimum values of these parameters. Overall, the analysis confirms that A2LiBiI6 compounds possess anisotropic mechanical characteristics, reflecting an optimized crystal structure with strong bonding and uniform microstructural features. Such attributes enhance their potential for application in advanced photovoltaic and optoelectronic devices.

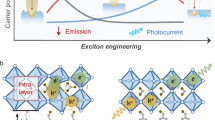

Evaluation for photocatalytic water splitting

The photocatalytic water splitting is a sustainable process that harnesses solar energy to generate hydrogen (H2), with semiconductor materials acting as photocatalysts to drive the redox reactions34,56. Two main half-reactions are involved in the process:

The efficiency of HER is governed by several intrinsic properties of the photocatalyst, such as its band gap energy, carrier recombination dynamics, spectral absorption range, and redox potential alignment. Optimal performance is achieved with materials exhibiting a small band gap (for visible light absorption), suppressed electron-hole recombination, extended carrier lifetimes, and appropriate conduction and valence band positions relative to the HER redox levels. Photocatalytic hydrogen production from water splitting fundamentally relies on the band edge alignment of the catalyst56. For spontaneous water splitting, the CBM must lie at a more negative potential than the H+/H2 reduction level (0 V vs. NHE, pH = 0), allowing photogenerated electrons to reduce protons. Simultaneously, the VBM must lie at a more positive potential than the H2O/O2 oxidation level (1.23 V vs. NHE) to drive the oxidation of water. The double perovskites Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6 were evaluated for this requirement by calculating their band edge positions using the following empirical Eqs. 15–1730:

Where χ is absolute electronegativity of compound, Eο is the vacuum scale potential of the standard hydrogen electrode (−4.5 eV), and Eg is the material’s bandgap. The electronegativities used were: χNa = 2.84, χK = 2.42, χRb = 2.33, χLi = 3.00, χBi = 4.12, and χI = 6.75, as reported by Bartolotti’s. Based on these values, the absolute electronegativity (χ) of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) was calculated to be 4.98 eV for Na2LiBiI6, 4.83 eV for K2LiBiI6, and 4.79 eV for Rb2LiBiI6.

The calculated CBM potentials were −0.3385 eV for Na2LiBiI6, −0.3055 eV for K2LiBiI6, and −0.363 eV for Rb2LiBiI6, while the corresponding VBM potentials were 1.5425 eV, 1.5575 eV, and 1.651 eV, respectively. These values indicate that in all three materials, the CBM lies more negative than 0 V (vs. NHE) to reduce H+ to H2, and the VBM lies more positive than 1.23 V (vs. NHE) to oxidize H2O to O2, as shown in Fig. 7, fulfilling the redox criteria for overall water splitting58. In addition to appropriate band alignment, the narrow bandgap of these materials enables effective solar harvesting across the UV and visible regions. Figure 5b) shows the absorption spectra with high coefficients, enhancing their capacity to capture incident photons and generate charge carriers efficiently. The favorable positioning of the band edges, coupled with high absorption capability and narrow bandgap, reduces recombination and promotes effective charge separation. These attributes make Na2LiBiI6, K2LiBiI6, and Rb2LiBiI6 materials for efficient, solar-driven hydrogen production via photocatalytic water splitting.

In summary, the cubic-phase A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) double perovskites demonstrate a compelling combination of thermodynamic, dynamic, electronic, optical, and mechanical stability, making them auspicious contenders for optoelectronic and photocatalytic water splitting applications. The negative formation energies, suitable tolerance factors, and absence of imaginary phonon modes confirm the structural robustness of these materials. The calculated band gaps (1.89–2.01 eV) correspond to the visible-light region (∼620–660 nm), making A2LiBiI6 halides promising candidates for photocatalytic applications under solar illumination. Their indirect band gaps, spanning the visible range and tunable with A-site ionic radius, along with favorable dielectric properties, highlight their potential for efficient light absorption. Furthermore, mechanical analyses indicate ductile behavior and elastic stability, supporting their viability for practical deployment. These findings provide a foundational framework for the rational design of lead-free, cost-effective, sustainable materials for large-scale solar energy conversion and hydrogen production. As a result of this research, a framework for designing economic photocatalytic materials for large-scale HER and OER is laid.

Methods

Computational framework

The physical properties of A2LiBiI6 (A = Na, K, Rb) were systematically analyzed using DFT-based simulations employed in the CASTEP code59. These compounds exhibit a cubic double perovskite framework, wherein the A-site is designated for monovalent alkali metal cations (Na⁺, K⁺, Rb⁺), while Li+ and Bi+3 alternately occupy the B-site. The halide ions (I-) occupy the X-site in an octahedral coordination environment, satisfying the general formula A2BB’X660.

Pseudopotentials and exchange-correlation functional

Ultrasoft pseudopotentials61 were employed, with the following valence electronic configurations: Na (2 s², 2p⁶, 3 s¹), K (3 s², 3p⁶, 4 s¹), Rb (3 s², 4p⁶, 5 s¹), Li (1 s², 2 s¹), Bi (6 s², 6p³), and I (5 s², 5p⁵). The exchange-correlation interactions within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) model were employed to describe the material. This approach was executed with the framework of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) scheme62.

Brillouin zone sampling and energy cutoff

Using the Monkhorst-Pack scheme63, the Brillouin zone integral was employed to sample a 6 × 6 × 6 grid, with a cutoff energy of 340 eV. Electronic structures were obtained at the GGA-PBE level (CASTEP); although GGA underestimates absolute band gaps, prior benchmarks confirm that hybrid functionals such as YS-PBE0 (Wien2K) yield larger but consistent gaps while preserving band ordering and orbital character32.

Geometry optimization

The following geometry optimization parameters were used to ensure stable energy convergence of the system: An energy self-consistent convergence tolerance of 2 × 10−5 eVatom-1 was set for the iterative solution of the Kohn-Sham equations64,65,66,67, together with a maximum atomic displacement of 0.002 \(\dot{{\rm{A}}}\), a stress tolerance of 0.1 GPa, and a force convergence criterion of 0.05 \({\rm{eV}}/\dot{{\rm{A}}}\).

Data availability

Data relevant to this study is available upon request; please direct all inquiries to the corresponding author.

References

Ferreira, A. et al. Economic overview of the use and production of photovoltaic solar energy in brazil. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 181–191 (2018).

Megía, P. J., Vizcaíno, A. J., Calles, J. A. & Carrero, A. Hydrogen production technologies: from fossil fuels toward renewable sources. A mini review. Energy Fuels 35, 16403–16415 (2021).

Hamad, Y. M. et al. A design for hydrogen production and dispensing for northeastern United States, along with its infrastructural development timeline. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 39, 9943–9961 (2014).

Liu, G., Sheng, Y., Ager, J. W., Kraft, M. & Xu, R. Research advances towards large-scale solar hydrogen production from water. EnergyChem 1, 100014 (2019).

Yue, M. et al. Hydrogen energy systems: a critical review of technologies, applications, trends and challenges. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 146, 111180 (2021).

Roes, A. & Patel, M. Ex-ante environmental assessments of novel technologies–Improved caprolactam catalysis and hydrogen storage. J. Clean. Prod. 19, 1659–1667 (2011).

Yilanci, A., Dincer, I. & Ozturk, H. K. A review on solar-hydrogen/fuel cell hybrid energy systems for stationary applications. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 35, 231–244 (2009).

Hosseini, S. E. & Wahid, M. A. Hydrogen production from renewable and sustainable energy resources: promising green energy carrier for clean development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 57, 850–866 (2016).

Siwal, S. S. et al. Advanced thermochemical conversion technologies used for energy generation: advancement and prospects. Fuel 321, 124107 (2022).

Oni, A., Anaya, K., Giwa, T., Di Lullo, G. & Kumar, A. Comparative assessment of blue hydrogen from steam methane reforming, autothermal reforming, and natural gas decomposition technologies for natural gas-producing regions. Energy Convers. Manag. 254, 115245 (2022).

Energy, B. & Outlook, B. E. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Energy%2C+B.+%26+Outlook%2C+B.+E.+++++%28BP%2C+2019%29&btnG= (BP, 2019).

Fan, L., Tu, Z. & Chan, S. H. Recent development of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies: a review. Energy Rep. 7, 8421–8446 (2021).

Miteva, P. P. Investing in Clean Hydrogen. https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Fan%2C+L.%2C+Tu%2C+Z.+%26+Chan%2C+S.+H.+Recent+development+of+hydrogen+and+fuel+cell+technologies%3A+A+review.+Energy+Reports+7%2C+8421-8446+%282021%29.+doi.org%2F10.1016%2Fj.egyr.2021.08.003+13%09Miteva%2C+P.+P.+Investing+in+Clean+Hydrogen.++%282024%29.&btnG= (2024).

Rahman, M. Z. et al. Insight into the physical properties of the chalcogenide XZrS3 (X= Ca, Ba) perovskites: a first-principles computation. J. Electron. Mater. 53, 3775–3791 (2024).

Tarekuzzaman, M., Parves, M. S., Rahman, M. Z. & Hasan, S. S. Cesium-Based perovskite hydrides: a theoretical insight into hydrogen storage and optoelectronic characteristics. Solid State Commun. 404, 116043 (2025).

Hodges, A. et al. A high-performance capillary-fed electrolysis cell promises more cost-competitive renewable hydrogen. Nat. Commun. 13, 1304 (2022).

Jain, S. M., Edvinsson, T. & Durrant, J. R. Green fabrication of stable lead-free bismuth based perovskite solar cells using a non-toxic solvent. Commun. Chem. 2, 91 (2019).

Meyer, E., Mutukwa, D., Zingwe, N. & Taziwa, R. Lead-free halide double perovskites: a review of the structural, optical, and stability properties as well as their viability to replace lead halide perovskites. Metals 8, 667 (2018).

Slavney, A. H. et al. Defect-induced band-edge reconstruction of a bismuth-halide double perovskite for visible-light absorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 5015–5018 (2017).

McClure, E. T., Ball, M. R., Windl, W. & Woodward, P. M. Cs2AgBiX6 (X = Br, Cl): new visible light absorbing, lead-free halide perovskite semiconductors. Chem. Mater. 28, 1348–1354 (2016).

Slavney, A. H., Hu, T., Lindenberg, A. M. & Karunadasa, H. I. A Bismuth-halide double perovskite with long carrier recombination lifetime for photovoltaic applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 2138–2141 (216).

Du, K.-z., Meng, W., Wang, X., Yan, Y. & Mitzi, D. B. Bandgap engineering of lead-free double perovskite Cs2AgBiBr6 through trivalent metal alloying. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8158–8162 (2017).

Kumarc, S. & Vermad, A. S. Investigations of lead free halides in sodium based double perovskites Cs2NaBiX6 (X= Cl, Br, I): an ab intio study. East. Eur. J. Phys. 16, 74–80 (2021).

Choudhary, S., Tomar, S., Kumar, D., Kumar, S. & Verma, A. S. Investigations of Lead Free Halides in Sodium Based Double Perovskites Cs2NaBiX6(X=Cl, Br, I): an Ab Intio Study. East Eur. J. Phys. 74–80, https://doi.org/10.26565/2312-4334-2021-3-11 (2021).

Darsan, A. S. & Pandikumar, A. Recent research progress on metal halide perovskite based visible light active photoanode for photoelectrochemical water splitting. Mater. Sci. Semiconduct. Process 174, 108203 (2024).

Rizwan, M. et al. Structural, electronic and optical properties of copper-doped SrTiO3 perovskite: a DFT study. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 552, 52–57 (2019).

Rahman, N. et al. Theoretical investigations of double perovskites Rb2YCuX6 (X= Cl, F) for green energy applications: DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 193, 112171 (2024).

Goldschmidt, V. M. Die gesetze der krystallochemie. Naturwissenschaften 14, 477–485 (1926).

Shannon, R. D. Revised effective ionic radii and systematic studies of interatomic distances in halides and chalcogenides. Found. Crystallogr. 32, 751–767 (1976).

Ullah, M. A., Rizwan, M. & Riaz, K. N. Innovative complex perovskites for efficient hydrogen Evolution: a DFT-Based design strategy. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 301, 117195 (2024).

Bouferrache, K. et al. Study of structural, elastic, electronic, optical, magnetic and thermoelectric characteristics of Hexafluoromanganets A2MnF6 (A= Cs, Rb, K) cubic double perovskites. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 308, 117550 (2024).

Camargo-Martínez, J. & Baquero, R. The band gap problem: the accuracy of the Wien2k code confronted. Rev. mex. fis 59, 453–459 (2013).

Tu, H. et al. Unveiling the impact of microstructure alterations on photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide preparation via DFT prediction and analysis. Energy Environ. Mater. e70016. https://doi.org/10.1002/eem2.70016 (2025).

Gillani, S. et al. An extensive screening of unique SrHfO3 perovskite for hydrogen evolution and excellent photocatalytic water splitting application by DFT. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 207, 112939 (2025).

Jena, S., Priyambada, A., Behera, S. S. & Parida, P. Multifaceted DFT analysis of defect chalcopyrite-type semiconductor ZnGa 2 S 4: dynamic stability and thermoelectric efficiency. Sustain. Energy Fuels 9, 3343–3353 (2025).

Akeb, Y., Khodja, A.T., Boussaa, S.A., Drablia, S. & Boulechfar, R. Comprehensive DFT study of AgBeCl₃ perovskite structural and mechanical properties, electronic, optical, thermoelectric behavior, and dynamical stability via phonon analysis. Chem. Phys. 598, 112832 (2025).

Khalil, A. et al. Investigation of structural, electronic, phonon, optical and mechanical properties of CoBiX (X= Ti, Zr) direct bandgap semiconductors. Mater. Sci. Semiconductor Process. 188, 109238 (2025).

Yang, Z. Y., Zhong, T. Y., Zhang, Y. X., Feng, J. & Ge, Z. H. Ultralow lattice thermal conductivity and high ZT beyond 1 realized in Bi2S3 nanocomposites via bottom-up structure design. Small 21, 2409618 (2025).

Algethami, N. et al. First-principles study of structural, elastic, electronic and optical properties of XRbCl3 (X= Ca, Ba) perovskite compounds. Results Phys. 70, 108163 (2025).

Ehrenreich, H. & Cohen, M. H. Self-consistent field approach to the many-electron problem. Phys. Rev. 115, 786 (1959).

Mahmood, Q. et al. Study of new lead-free double perovskites halides Tl2TiX6 (X= Cl, Br, I) for solar cells and renewable energy devices. J. Solid State Chem. 308, 122887 (2022).

Lim, S. J., Schleife, A. & Smith, A. M. Optical determination of crystal phase in semiconductor nanocrystals. Nat. Commun. 8, 14849 (2017).

Mumtaz, S. et al. Unveiling pressure-driven tunability of structural, electronic, mechanical and optical characteristics in CsPbBr3 based on a DFT study. Materials 8, 100761 (2025).

Ferreira, A. et al. Elastic softness of hybrid lead halide perovskites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 085502 (2018).

Fatima, T. et al. Computational insights into the structural, electronic, mechanical, and optical properties of Cu, Ge, and Au-doped CsTiO3 for Optoelectronic Applications. Comput. Condensed Matter e01056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cocom.2025.e01056 (2025).

Parosh, M. B. H. et al. Investigation of physical properties of NaBaX3 (X= Cl, Br, and I) cubic perovskites using first-principles density-functional theory. Braz. J. Phys. 55, 1–18 (2025).

Hasan, M. M. et al. Exploring pressure-driven semiconducting to metallic phase transition in lead-free InGeX3 (X= F, Cl) perovskites with tunable optoelectronic and mechanical properties via DFT. Phys. B: Condens. Matter 705, 417083 (2025).

Giri, R. K. et al. First principle insights and experimental investigations of the electronic and optical properties of CuInS 2 single crystals. Mater. Adv. 4, 3246–3256 (2023).

El Goutni, M. E. A., Remil, A., Saidi, M., Batouche, M. & Seddik, T. Probing Cs2OsX6 (X= Cl, Br, I) double perovskites via DFT: prospects for photocatalytic water splitting and CO2 reduction. Eur. Phys. J. B 98, 130 (2025).

Murtaza, H. et al. The prediction of hydrogen storage capacity and solar water splitting applications of Rb2AlXH6 (X= In, Tl) perovskite halides: a DFT study. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 198, 112427 (2025).

Tang, L. et al. Enhancing perovskite electrocatalysis through synergistic functionalization of B-site cation for efficient water splitting. Chem. Eng. J. 401, 126082 (2020).

Archi, M., Bajjou, O. & Elhadadi, B. A comparative ab initio analysis of the stability, electronic, thermodynamic, mechanical, and hydrogen storage properties of SrZnH3 and SrLiH3 perovskite hydrides through DFT and AIMD Approaches. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 105, 759–770 (2025).

El Akkel, M. & Ez-Zahraouy, H. First-principles study of triaxial strain effect on structural, mechanical, electronic, optical, and photocatalytic properties of K2SeBr6 for solar hydrogen production. Chem. Phys. 595, 112739 (2025).

Poisson, S.-D. Mémoire sur l'équilibre et le mouvement des corps élastiques (F. Didot, 1828).

Greaves, G. N., Greer, A. L., Lakes, R. S. & Rouxel, T. Poisson’s ratio and modern materials. Nat. Mater. 10, 823–837 (2011).

Naeem, H. et al. Exploring novel characteristics of GaBaX3 (X= F, Cl, Br, I, H) for energy harvesting applications: a DFT-based analysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 105, 203–213 (2025).

Gaillac, R., Pullumbi, P. & Coudert, F.-X. ELATE: an open-source online application for analysis and visualization of elastic tensors. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 28, 275201 (2016).

Ech-charqy, Z., El Badraoui, A., Elkhou, A., Ziati, M. & Ez-Zahraouy, H. Effect of sulfur doping on the electronic structures, optical and photocatalytic properties of KTaO3 perovskites: DFT calculations. Chem. Phys. 596, 112759 (2025).

Clark, S. J. et al. First principles methods using CASTEP. Z. krist. cryst. Mater. 220, 567–570 (2005).

Es-Smairi, A. et al. DFT insights into the structural, stability, elastic, and optoelectronic characteristics of Na2LiZF6 (Z= Ir and Rh) double perovskites for sustainable energy. J. Comput. Chem. 46, e70097 (2025).

Laasonen, K., Car, R., Lee, C. & Vanderbilt, D. Implementation of ultrasoft pseudopotentials in ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 43, 6796 (1991).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Evarestov, R. & Smirnov, V. Modification of the Monkhorst-Pack special points meshes in the Brillouin zone for density functional theory and Hartree-Fock calculations. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 70, 233101 (2004).

Zhou, B., Wang, Y. A. & Carter, E. A. Transferable local pseudopotentials derived via inversion of the Kohn-Sham equations in a bulk environment. Phys. Rev. B 69, 125109 (2004).

McClure, E. T., Ball, M. R., Windl, W. & Woodward, P. M. Cs2AgBiX6 (X= Br, Cl): new visible light absorbing, lead-free halide perovskite semiconductors. Chem. Mater. 28, 1348–1354 (2016).

Ji, Y., Lin, P., Ren, X. & He, L. Geometric and electronic structures of Cs 2 BB′ X 6 double perovskites: The importance of exact exchange. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033172 (2024).

Anbarasan, R., Sundar, J. K., Srinivasan, M. & Ramasamy, P. First principle insight on the structural, mechanical, electronic and optical properties of indirect band gap photovoltaic material Cs2NaBiX6 (X= Cl, Br, I). Comput. Condens. Matter 28, e00581 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge technical support from the University of Okara in this project. We are also grateful to the International Islamic University, H-10, Islamabad 44000, Pakistan, for its support of our computing facilities. The authors declare that they did not receive any funding related to the study, manuscript preparation, or its publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Malik Muhammad Asif **Iqbal:** Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Software, Paper editing. Muhammad Abaid **Ullah** : Visualization, Validation, Methodology.Muhammad **Kaleem:** Data Analysis, Methodology, Data curation, Visualization. Asif **Khan** : Conceptualization, Visualization, Data curation, Validation, Methodology.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iqbal, M.M.A., Ullah, M.A., Kaleem, M. et al. Quantum chemical investigation of A2LiBiI6 perovskites with Na, K, and Rb for photocatalytic water-splitting application. npj Clean Energy 2, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44406-025-00014-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44406-025-00014-4