Abstract

Low-cost mobile sensors can be used to collect PM2.5 concentration data throughout an entire city. However, identifying air pollution hotspots from the data is challenging due to the uneven spatial sampling, temporal variations in the background air quality, and the dynamism of urban air pollution sources. This study proposes a method to identify urban PM2.5 hotspots that addresses these challenges, involving four steps: (1) equip citizen scientists with mobile PM2.5 sensors while they travel; (2) normalise the raw data to remove the influence of background ambient pollution levels; (3) fit a Gaussian process regression model to the normalised values; (4) calculate spatially explicit ‘hotspot scores’ using the probabilistic framework of Gaussian processes, which summarise the relative pollution levels throughout the city. We apply our method to create the first ever map of PM2.5 pollution in Kigali, Rwanda, at a 200m resolution, where we uncover several pollution hotspots. We also evaluate our method using simulated mobile sensing data for Beijing, China, where we show that the hotspot scores capture the ground-truth spatial PM2.5 distribution. Thanks to the use of open-source software and low-cost sensors, our method can be re-applied globally to help fill the gap in urban air quality information.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Air pollution is considered ‘the single biggest environmental threat to human health’ by the World Health Organisation1. A particularly harmful category of pollutants is PM2.5, defined as particulate matter with an aerodynamic diameter ≤2.5 μm. PM2.5 particulates are small enough to penetrate deep into the lungs and sometimes even the bloodstream, and are associated with a wide range of adverse respiratory2, cardiovascular3, and cerebrovascular health outcomes4. Increased exposure to ambient PM2.5 has also been linked to adverse birth outcomes5 and increased incidence of diabetes mellitus6. An estimated 4.1 million deaths in 2019 can be attributed to long-term ambient PM2.5 exposure7, and it is estimated that PM2.5-attributable deaths increased in all global regions except Europe and the Americas from 2000 to 20198, a concerning trend.

In 2015, the 193 member states of the United Nations ratified the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 11.6 which seeks to improve urban air quality by 2030. Despite receiving global support, current PM2.5 monitoring infrastructure is insufficient to measure whether SDG 11.6 is achieved. As of 2019, the majority (141) of the world’s countries had no regular PM2.5 monitoring at all, and the global mean population distance to a PM2.5 monitor was 220 km9. A more recent analysis estimates that in-situ PM2.5 measurements are missing for over 50% of the world’s urban population10. PM2.5 estimates based on satellite data are a welcome contribution to filling the data gap (e.g., ref. 11). However, satellite estimates often have a granularity of hundreds of meters or even kilometers, which is too coarse to capture the full variability of PM2.5 within a city and accurately assess citizens’ personal exposure. Furthermore, satellite estimates can exhibit errors in the range 22–85% when they are not calibrated by ground PM2.5 measurements12.

Low-cost sensors are a promising alternative to satellite data, and several studies have already explored using the technology to estimate the concentration of PM2.5 throughout an urban area. Low-cost sensors can be installed at fixed sites to increase the spatial coverage of the city’s monitoring network13,14,15. An alternative approach that more easily scales for city-wide data capture is mobile sensing, wherein the sensors are transported while they record geolocated air quality measurements. Mobile sensors can complement a stationary monitoring network to support spatial air quality estimation16,17 or can operate as a standalone system for mapping pollution levels. Several studies have deployed mobile sensors along predetermined routes on multiple different days and/or at different times of the day18,19,20. This approach allows one to analyse how pollution levels vary along a fixed route, as well as how pollution varies across time when the location is controlled. However, deploying sensors along prescribed routes is not optimal for assessing pollution exposure because the routes may differ from routes that people usually take, and the spatial coverage is often limited. Other studies have instead fit mobile sensors to people21 or vehicles such as taxis22,23 or trams24 while going about their daily business. This leads to PM2.5 concentrations data that are more informative about people’s day-to-day exposure and the data will often cover a larger spatial area than predetermined routes.

Once pollutant concentrations have been recorded with mobile sensing, a key question is where the air pollution hotspots are in the city. A hotspot is a location where the average pollution level exceeds that of the surrounding area. Identifying hotspots is relevant from a health perspective because short-term exposure to high levels of air pollution has been positively associated with increased inflammatory markers in the lungs25 and with increased all-cause mortality for the pollutants PM2.5, PM10, NO2 and O326. The evidence suggests that health outcomes are not just determined by average PM2.5 exposure, but also by the maximum or near-maximum PM2.5 exposure. Additionally, hotspots are relevant from a policymaking perspective, as they constitute locations where policymakers can focus their clean air initiatives to achieve the maximal improvement in health outcomes. Hotspot detection can also help to pinpoint PM2.5 pollution sources that were previously unknown27.

In this study we propose an urban PM2.5 hotspot-detection method that combines mobile sensing data with Gaussian process regression. Gaussian process regression has three particularly attractive properties for modelling PM2.5 concentrations data: (1) it allows for a rich specification of the target function28; (2) it is flexible, accommodating diverse data types and (3) compared to many geospatial models, specifying a Gaussian process requires little expert intervention29,30. These advantageous properties have motivated increased research into applying Gaussian process regression to predict PM2.5 concentrations31,32,33 and to interpolate sparse PM2.5 concentrations data34,35. However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to apply Gaussian process regression with the explicit aim of PM2.5 hotspot detection from mobile sensing data.

Our method contributes to the growing body of literature on identifying urban PM2.5 hotspots. One study36 considers data from stationary PM2.5 sensors and identify hotspots based on the frequency, scale, and consistency with which pollution levels exceed a given threshold (see also ref. 37). However, their approach is designed for fixed PM2.5 monitoring stations rather than for the uneven sampling pattern and wide spatial coverage of mobile sensing. Another approach which is more compatible with mobile sensing considers a ‘window’ around every observation, consisting either of neighbouring observations38 or neighbouring pixels of gridded observations39, and identifies PM2.5 spikes within these windows as hotspots. Although effective for localized hotspot detection, these window-based approaches lack a shared baseline across windows, making them less suitable for city-wide hotspot identification. The \({G}_{i}^{* }\) statistic40,41 is another popular choice for PM2.5 hotspot identification18,42. For every location i in a spatial grid, \({G}_{i}^{* }\) is calculated as the weighted sum of the PM2.5 values at the other locations j, with the weights wi,j being inversely proportional to the distance di,j between the location pairs40,41. A location i is considered a hotspot if its \({G}_{i}^{* }\) statistic value is significantly larger than one would expect under a spatially-random distribution of the PM2.5 observations. A limitation is that the \({G}_{i}^{* }\) are merely descriptive statistics about the clustering of observed data, and they convey less information than probabilistic approaches which also report the localised variability in the observed data.

To address these limitations, we propose a Gaussian process-based approach that is compatible with spatially- and temporally-uneven mobile sensing data, identifies hotspots relative to the whole city, and outputs spatially-explicit hotspot scores that capture the variability in the observed data. We proceed to evaluate the PM2.5 hotspot-detection method on two datasets. The first is a mobile sensing dataset that we gathered in Kigali, Rwanda, in September 2021. The population of Kigali has grown from tens of thousands of people to over 1 million in the last 50 years, yet as of 2021 the city had no publicly-accessible reference PM2.5 monitoring station. Kigali is therefore a good representation of a city in a low-income country with an air quality data gap that mobile sensing can help to resolve, in pursuit of SDG 11.6. The second dataset comprises seasonal estimates of the average PM2.5 concentrations for Beijing. Published by Wang et al.43, the dataset is based on several information sources, such as satellite top-of-atmosphere data, traffic emissions and land use data, and contains average PM2.5 estimates at a spatial resolution of 30 m. Treating the Beijing dataset as a ‘ground truth’ for hotspot locations, we first simulate mobile sensing data, and then evaluate whether our method can successfully reconstruct the spatial PM2.5 distribution from the simulated mobile sensing data.

Results

Kigali data

After processing, the Kigali dataset consists of 2.02 million observations of the PM2.5 concentration in and around Kigali. With one measurement per second, this corresponds to >562 h of data. In general, tiles with the greatest number of measurements encompass a stretch of a major road (Fig. 1a), and the measurements are concentrated in the city centre more than the outskirts. The median number of observations per tile is 100 and there is a large gulf between the minimum (1) and maximum (48,670), reflecting the uneven spatial sampling. Regarding the temporal density, PM2.5 observations are available at every hour of the day (Figure 1b). The least sampled hours are 01:00-03:00 where fewer than 1000 observations were recorded across the twenty days considered. Meanwhile, between 06:00 and 21:00 there is an abundance of data, with at least 50K observations per hourly interval. The temporal distribution reflects that the drivers carried out most of their work during daylight hours. Between calendar days the sampling intensity was fairly consistent: the mean number of measurements was 101.2K per day, with a minimum of 71K on Sunday 5th September 2021 and a maximum of 134.3K on Monday 13th September 2021.

In panel (a), the colour of every 200 m × 200 m grid tile reflects the number of measurements recorded there, revealing that data collection was concentrated in the city centre and along main roads. Panel (b) shows the number of measurements per hour of day, revealing that most measurements were recorded during daylight hours, which were approximately 06:00-18:00 in Kigali during September 2021.

The average PM2.5 concentration recorded exhibits a diurnal pattern (Fig. 2), with the mean concentration peaking in the early morning and again in the late afternoon and evening (Fig. 2a). The standard deviation of the PM2.5 measurements is smallest at night (00:00–04:00) and larger throughout the rest of the day, although given the lack of nighttime observations, the nighttime standard deviation estimates are less reliable than those in the daytime. This diurnal pattern is similar on every day of the week (Fig. 2b), and closely matches the pattern observed in previous PM2.5 measurement studies in Kigali44,45.

An interesting feature is that during the morning (07:00–11:00), average PM2.5 is clearly lower on Sundays than on any other weekday, but from 12:00 onwards the PM2.5 level on Sunday resembles the other weekdays again. This coincides with the timing of the ‘car-free Sundays’ scheme in Kigali 44. On the first and third Sunday of every month, several main roads in Kigali are closed to motorized vehicles between 07:00 and 10:00, and pedestrians are encouraged to gather in the vacant streets for group exercise sessions. At 10:00 all roads are re-opened. Two out of the three Sundays within our data collection campaign were ‘car-free’, which could plausibly affect the air quality encountered by the mobile sensors, although more robust evidence would be needed to establish a causal link between the scheme and decreased ambient pollution levels. Figure 2b also suggests that the mean PM2.5 concentration increases sharply on Friday nights and dips during the early hours of Wednesday morning. However, these extremes both correspond to a small number of measurements, so probably do not reflect a typical trend.

We argue that because our data is gathered while the drivers carry out their usual jobs - as opposed to driving along pre-determined routes - the average PM2.5 concentrations recorded are representative of the PM2.5 exposure of Kigali’s road users. It is therefore alarming to see that the mean PM2.5 concentration exceeds the WHO’s recommended level of 5 μg/m3 at all hours of the day. The overall mean PM2.5 concentration in the Kigali data is 44.61 μg/m3 with a standard deviation of 39.47 μg/m3. Furthermore, 91.9% of PM2.5 concentration observations exceed 15 μg/m3, whereas the WHO guidelines recommend that PM2.5 exposure should not exceed 15 μg/m3 for any more than a handful of days in the year. Our data supports previous studies finding that air pollution in Kigali often exceeds the safe limits set by the WHO44,45,46, and provides evidence that the air quality encountered by road users is dangerously unhealthy as a result.

Hotspot detection in Kigali

We then calculated the hotspot scores (h(j))j∈J from the Kigali mobile sensing data. For the spatial resolution we chose 200 × 200 m as a compromise between a high spatial granularity and a large number of observations per tile. After the scores had been computed, we classified every tile j ∈ J as follows: if h(j) > 0.8 then j is a hotspot; if h(j) < 0.2 then j is a coldspot; otherwise, j is neutral, although these thresholds can naturally be changed in different mobile sensing studies. Using this classification, 184 of the tiles are hotspots, 60 of the tiles are coldspots, and 3919 of the tiles are neutral. The mean and standard deviation of observed PM2.5 concentrations in hotspot tiles is 46.3 ± 22.3 μg/m3; in coldspot tiles, 26.5 ± 0.8 μg/m3; and in neutral tiles, 39.1 ± 42.3 μg/m3. Although hotspots only account for 4.4% of the gridded area, over 21.1% of observations are recorded in tiles classified as hotspots. This implies that the drivers spent a disproportionate amount of time in the most polluted locations in the city, highlighting the importance of measures to tackle Kigali’s urban hotspots.

The hotspot scores are variegated (Fig. 3a), reflecting the flexibility of Gaussian process regression models. A large hotspot in Kigali is centered around 1°56’31”S, 30°2’36”E, which is the intersection between four major roads: the KN1, KN7, KN20 and Kigali-Gatuna. Here, the hotspot scores are among the largest for the whole city, with hotspot scores >0.9 in several neighbouring tiles, indicating that ambient PM2.5 concentrations in this area often exceed the city-wide median. Google Street View images of this neighbourhood (Fig. 3b) reveal that there are multiple lanes of traffic, several petrol stations, and pockets of exposed sand (e.g., at the intersection between the KN1 and Kigali-Gatuna roads). High hotspot scores are continually observed along the four major roads for at least a kilometer as they depart from this intersection. A second prominent hotspot is in the South of the Kicukiro neighbourhood, around 1°59’ 01.9 ”S 30°06’08.7”E. Two neighbouring tiles have hotspot scores > 0.9, encompassing a stretch of the multi-lane KK15 highway and a local tyre retreading company. For comparison, Google Street View images were also inspected at a coldspot along the KG 649 street (Fig. 3c), where the model assigned low hotspot scores (<0.2). The Google Street View images suggest that this is a low-traffic area, with few visible vehicles. Open fields directly border the road rather than denser developments like residential housing, and the road is lined with trees.

In panel (a), the colour of every 200 × 200 m grid tile reflects the hotspot score estimated from the Gaussian process regression fit. Depicted are also illustrative Google Street View images from a hotspot (b) and coldspot (c) taken in December 2022 and February 2023, respectively. Hotspot scores were computed in every tile where there is at least one mobile sensing observation.

We also compared the hotspot locations with three public geographic datasets (Table 1): the road network from the OpenStreetMap47, the 10 m-resolution map of built-up surface area from the Global Human Settlement Layer48 - which estimates the proportion of land occupied by human settlements - and the 10m-resolution Rwanda digital elevation model (DEM) from the United Nations Development Programme49. A binary variable was calculated for every tile indicating whether or not it contains a stretch of a main road, and the built-up surface and DEM were upsampled to 200 m resolution by taking the mean. We found that 60% of hotspot tiles contain a main road compared to 33% of neutral and coldspot tiles, which suggests that traffic volume is a major contributor to spatial PM2.5 variability in Kigali. Additionally, the average built-up surface area among hotspot tiles is 27% versus 22% in neutral tiles and just 11% in coldspot tiles, and the rank correlation between hotspot scores and built-up surface area is ρ = 0.22. This implies that a higher density of human settlements is also associated with worse air quality. Meanwhile, the average elevation (m.a.sl) of hotspot tiles is around 60 m lower than non-hotspot tiles, and the rank correlation between mean elevation and the hotspot scores is negative ρ = − 0.08. Kigali is a notoriously hilly city and this result suggests that Kigali’s air quality is worse at lower altitudes, although more work would be needed to identify to what extent topographical factors are responsible versus socioeconomic and urban planning factors50.

Hotspot detection in Beijing

We then applied our hotspot-detection method on the simulated mobile sensing data in the two evaluation areas in Beijing and evaluated the results as described in Section “Validating the method”. The hotspot scores correspond closely with the true spatial PM2.5 profiles. In Beijing LP (Fig. 4a, b), the figure-of-eight shape in the Northwest is clearly identifiable and the major hotspot along the right and bottom of this quadrant is also evident. One also sees that the model delineates the boundaries between high and low pollution, although a caveat is that the estimated boundaries are much smoother than the reality. The boundary between the hotspot on the right and the average pollution region in the middle is only a single tile wide (30 m). However, the method outputs a boundary seven tiles wide (210 m). This indicates that the Gaussian process regression surface is overly smooth, and does not effectively model the variations in PM2.5 concentration across small spatial scales. In Beijing CLT (Fig. 4c, d), the hotspot scores also match the main spatial contours of PM2.5 pollution. However, the spatial profile of the hotspot scores is again very smooth. In particular, the small patches of varying PM2.5 levels in the left of the quadrant are smoothed over in the hotspot scores.

Panels (a, c) depict the spatial PM2.5 distribution from ref. Wang et al.43 and panels (b, d) depict the hotspot scores calculated by our method. The colours correspond to the intensity for every 30 × 30 m grid tile. The hotspot scores generally match the spatial pollution pattern in the city, although the sharp boundaries between high and low pollution are sometimes smoothed over.

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient value ρ between the hotspot scores and the spatial PM2.5 averages is high in both evaluation areas. When all grid tiles are included, ρ = 0.8361 in Beijing CLT and ρ = 0.7451 in Beijing LP. These values are close to the maximum achievable correlation of 1, which supports the fact that our method effectively reconstructs the spatial profile of PM2.5 pollution from spatiotemporally sparse mobile sensing data. We also experimented with re-computing the correlation while filtering to the grid tiles where n_measurements > t and varying the minimum number t, to investigate whether the spatial distribution of the hotspot scores is more accurate among the more frequently sampled grid tiles. Figure 5 shows that as t increases, the correlation increases markedly in Beijing LP but remains stable in Beijing CLT. This suggests that increasing the frequency with which the mobile sensors visit all the tiles could improve the accuracy of the resulting hotspot classification. Future mobile monitoring studies should therefore attempt to ensure that all areas of interest in the city are visited several times by the drivers carrying the sensors.

Probabilistic calibration

Overall, the hotspot scores are reasonably well-calibrated as posterior probabilities (Fig. 6). In both areas, the exceedance proportions in the holdout test set were found to increase monotonically with the hotspot scores estimated on the training set. I.e., the greater the hotspot score in a tile, the more frequently the PM2.5 concentration is indeed exceeding the city-wide median. In Beijing CLT, the calibration is particularly good in the top three bins of hotspot scores, where the calibration curve aligns with the line of perfect calibration. However, for lower bins, the model was generally overconfident: e.g., among tiles where the hotspot score was in the interval (0.3, 0.4], f(xi) exceeds median(y) for only 9.3% of the observations. In Beijing LP, the calibration curve has an inverse C-shape: the hotspot scores and the observed exceedance proportions are close together at lower and higher values of the hotspot scores, whereas in between the extremities, the calibration curve diverges from the ideal and the model is severely over-confident. Overall, the calibration curves suggest that the hotspot scores are more accurate at extreme hotspots and coldspots, and less accurate in the tiles where the average pollution is close to the city-wide average.

Reliability diagrams (a, c) compare the predicted hotspot scores against the observed exceedance proportions, before (in blue) and after (in pink) an isotonic regression calibration is applied. Isotonic regression fits (b, d) illustrate how the isotonic regression fit transforms the hotspot scores (x-axis) into calibrated hotspot scores (y-axis).

The calibration procedure corrects for the estimation errors (Fig. 6b, d). The correction is particularly acute among the least-polluted tiles, where the uncalibrated model tends to over-estimate the exceedance proportion. For example, in Beijing CLT (Fig. 6b), tiles with a hotspot score up to 0.3307 have a calibrated hotspot score of 0.0855, while in Beijing LP (Fig. 6d), tiles with a hotspot score in the range 0.3968–0.4228 have a calibrated hotspot score of 0.1618. The calibration procedure greatly improves key metrics computed on the holdout test set. In Beijing CLT, calibration reduces the ECE from 0.1527 to 0.0081 and the Brier score from 0.2085 to 0.1637. In Beijing LP, calibration reduces the ECE from 0.2294 to 0.0441 and the Brier score from 0.2270 to 0.1688. After transformation with the isotonic regressor, the reliability curve aligns very well with the ideal diagonal curve in both areas (Fig. 6a, c).

Discussion

Short-term exposure to high PM2.5 concentrations is associated with increased PM-related mortality and a wide range of adverse health outcomes51,52, hence identifying and cleaning up PM2.5 hotspots is a major opportunity to improve public health, in pursuit of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 11.6. This study presents a method for identifying PM2.5 hotspots in an urban area, combining mobile sensing with Gaussian process regression. The method consists of four steps: (1) equip a fleet of vehicles with low-cost PM2.5 sensors to measure the air quality; (2) normalise the raw observations for background concentrations by subtracting the median concentration from the previous xw minutes (in this case study, xw = 15); (3) fit a Gaussian process regression surface to the normalised observations, and (4) compute posterior probabilities across a spatial grid that the normalised PM2.5 concentration exceeds the city-wide median, which are the ‘hotspot scores’. Using observed data from Kigali, Rwanda, we showed that our method is compatible with the data from real-world mobile sensing campaigns, and that the hotspots detected by the method coincide with main roads, denser urban settlements, and lower altitude regions. Although previous air quality studies have been performed in Kigali44,45,46, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to present the spatial distribution of PM2.5 pollution throughout the entire city of Kigali.

Using simulated mobile sensing data from Beijing, China, we also showed that the hotspot scores preserve the spatial profile of PM2.5 concentrations in a city. I.e., if an area of the city is more polluted than average, then its ‘hotspot score’ is typically higher, and vice versa. We also showed that the hotspot scores are probabilistically well-calibrated, and that the probabilities can be made even more accurate with isotonic regression, an out-of-the-box calibration regressor. These properties suggest that our hotspot scores are apt for identifying PM2.5 hotspots in an urban area, which corroborates the growing enthusiasm for applying Gaussian process regression in spatial statistics problems28,29.

Our hotspot-detection method is designed for urban areas in low-income countries, where PM2.5 pollution is among the worst in the world and yet fixed PM2.5 monitoring equipment is often lacking10. To this end, only low-cost sensors are used for the data collection, and a background normalisation procedure is proposed that does not require measurements from a fixed PM2.5 monitoring station. Additionally, all computations and analysis were performed with free, open-source software (R, Python, QGIS) and data (OSM) so that the method can be recreated without expensive software licences. These considerations should remove some of the barriers for practitioners in lower-income countries to apply our method for their own case study. Furthermore, although Gaussian process modelling is typically computationally intensive, we propose an implementation that greatly reduces the computational requirements of the calculations based on simple bagging with subsamples of the data, as explained in Section “Practical implementation”. For larger urban areas than Kigali or denser mobile sensing campaigns where more data is collected, it is possible that further steps would still be needed to reduce the computational runtime. In that case, future practitioners could explore combining the bagging procedure with other methods for simplifying Gaussian process calculations such as inducing-point methods53 or methods of distributed computing54.

In our method, PM2.5 data is collected by equipping a fleet of on-road vehicles with low-cost sensors, then measuring the ambient air quality while the vehicles drive around as usual. We argue that the hotspots identified by our method are therefore highly relevant to the pollution exposure of local road users. In the Kigali case study, we found that the drivers spent a disproportionate amount of time in the most polluted locations in the city. There is growing research to suggest that the air quality within cars correlates closely with the outer air quality, particularly when the car windows are open55. Moreover, motorbike users typically breathe more polluted air than car users because they are less insulated from the outer air56. Accordingly, improving on-road air quality would directly improve the air quality encountered by road users, and our method suggests some priority locations for such an effort.

A challenge in mobile sensing campaigns is data sparsity, which can reduce the accuracy of air quality estimates17,57,58. Although this study benefitted from a large dataset of 2.02 million observations in Kigali with a wide spatiotemporal coverage, it is therefore worth considering how our method would perform in a data-sparse context. If the data coverage is low during certain hours of the data acquisition, then the main pitfall is that the rolling baseline may become biased and misrepresent the ambient pollution level, introducing error into the background-normalised values yi. Adjusting the window length xw according to the temporal resolution of the data is therefore important. As argued in ref. 59 and implemented in this study, a good criterion is that the background normalisation should produce a smooth temporal baseline. On the other hand, if a location has sparse data coverage, the pitfall is that the hotspot score may be less accurate there. Indeed, the results from Beijing LP (Fig. 5) suggest that the hotspot scores perform better in tiles with more mobile sensing observations. Adjusting the grid size to the spatial density of the data is therefore important, to ensure that the tiles are generally well-sampled. It is also important to choose an appropriate kernel for the Gaussian process regression model, because the kernel determines the degree of spatial interpolation in under-sampled areas. In the future, additional spatial covariates could be added to the model such as land-use60 to improve predictions in data-sparse tiles.

A shortcoming of the validation procedure is that the simulation process for the synthetic mobile sensing data in Beijing is overly simplified. Synthetic PM2.5 measurements were generated according to the process described in Section “Validating the method”, considering the road network, the spatial PM2.5 distribution in Beijing, the hourly trends in real-world monitoring station data, and two sources of stochastic measurement interference. State-of-the-art air pollution simulations generally incorporate atmospheric dispersion, explicit pollution sources, meteorological conditions, and sometimes traffic patterns61,62. However, the main purpose of the mobile sensing data simulation is to generate data with a high spatial and temporal resolution where the spatial PM2.5 profile is known, so that we can assess the accuracy of our method with reference to a ground truth. The realism of the air pollution dynamics is therefore of secondary importance. Nevertheless, a mobile sensing simulator with high spatiotemporal resolution and a greater incorporation of real-world air pollution dynamics would enable a more convincing validation.

In Section “Probabilistic calibration” we showed that calibrating the hotspot scores with an isotonic regression fit makes the posterior probability estimates more accurate. Therefore, an interesting direction for future work is to devise a calibration procedure that also works on real, non-simulated mobile sensing data. The calibration procedure here relies on the fact that noise-free observations of f(x) are available when the dataset is simulated, but this is not the case in a real-world mobile sensing campaign, where observations yi are theorised to be corrupted by some random noise. Future studies could consider combining the measurements from multiple sensors or triangulating the mobile measurements with a reference station in order to estimate f(x), and then using the estimates \(\widehat{f}({\bf{x}})\) to calibrate the hotspot scores. Nevertheless, we reiterate that the calibration transformation does not change the relative ranking of the grid tiles, so the hotspot scores can still be useful to identify hotspots even if poorly calibrated.

Methods

Mobile sensors

The air quality monitors used as part of the Kigali deployment, Fig. 7, were designed by open-seneca to be low-cost and portable, measuring geotagged PM2.5 data at a cadence of 1 Hz. The air quality monitors are based on an integrated circuit board and embedded software design, based on an ARM Cortex M4 microcontroller (STM32F405RGT6). The integrated circuit board controls an external Sensirion SPS30 particulate matter sensor and includes an on-board GNSS module (u-blox MAX-M8Q), a Sensirion SHTC3 temperature and humidity sensor, a display for data visualisation, and microSD card for data logging. All sensor readings and metadata are written as comma-separated values to an onboard microSD card. Further information on the hardware and software can be found on open-seneca GitHub page (https://github.com/open-seneca).

The monitor was a portable device that measured PM2.5, temperature, humidity, and GPS location at 1 Hz. It featured an onboard display and a Garmin-style mount for wearable or vehicle use. Raw data were stored locally on an SD card for manual upload. For the period of data collection in Kigali, the sensors were permanently installed and powered by the electric motorcycle’s onboard battery.

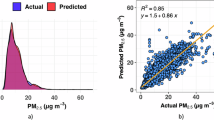

The Sensirion SPS30 particulate matter sensor is factory pre-calibrated (https://sensirion.com/products/catalog/SPS30). Prior to this study, a co-location of 50 sensors from the same batch as those used in Kigali showed excellent inter-sensor comparability. They achieved ±0.38 μg/m3 standard deviation from the mean over a 2 week period of co-location, as shown in Fig. 8, between the range of 0.1 and 28.0 μg/m3. The co-location performance was only evaluated while the sensors were stationary. However, during this period the sensors were exposed to wind - akin to moving on a bike - which makes us confident in their performance during mobile deployment.

Calibration against a reference station was not possible in Kigali due to the absence of a public reference station. However, given the nature of this study and the excellent out-of-the-box inter-sensor comparability, this was not necessary. For reference, the Supplementary Information presents a previous calibration of the same sensor type as those used in Kigali with a reference station at a different location. These calibration data were not used in this study, as the focus was on sensor inter-comparability rather than absolute values.

Experiment setup in Kigali

The study conducted in Kigali was designed to address air pollution concerns in Rwanda’s capital city. It employed 16 open-seneca air quality monitors, mounted on electric delivery motorbikes, part of Ampersand’s Rwanda Ltd fleet. The data collection occurred from 1st of September 2021 to the 1st of October 2021, as part of the Urban Pathways project, supported by the Wuppertal Institute, UN-Habitat, and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and funded by the International Climate Protection Initiative (IKI) of the German Ministry of the Environment.

The study was facilitated through collaboration with the University of Rwanda, the City of Kigali, the Urban Electric Mobility Initiative (UEMI), and Ampersand Rwanda Ltd. The method involved engaging professional delivery drivers as key participants, who carried sensors during their daily delivery routes. This approach ensured efficient data collection and coverage while adhering to the study’s time constraints.

The sensors were mounted at the front of the vehicle, behind the handlebars, and were continuously powered via the electric motorbike’s onboard USB outlet, as shown in Fig. 7. In the open-seneca air quality monitor, the inlet of the Sensirion SPS30 PM2.5 sensor faced opposite to the direction of travel to minimise the impact of direct wind on measurements, as the sensors are sensitive to airflow within the sampling channel.

At the conclusion of the data collection period, the microSD cards were manually retrieved from each of the 16 devices. The raw data from each sensor was stored in individual .csv files. These files contained time-series data for PM2.5, temperature, relative humidity, latitude, longitude, and GPS accuracy metrics, recorded at the 1 Hz frequency. The collected raw data was subsequently aggregated, cleaned, and processed to prepare it for spatial and temporal analysis.

Data processing

Duplicate rows in the data were removed, as well as any rows where the date, time, latitude or longitude are missing. The data were also filtered to a spatial bounding box encompassing Kigali, with latitude between 2° 9’36”S and 1°51’00”S, and longitude between 29°54’00”E and 30°15’00”E. Measurements were filtered to the 1st–20th of September 2021, the most active days of the study, and the temporal granularity of the data was reduced to one-second intervals: for all seconds where a device registered more than one measurement, the first measurement was retained and the rest were discarded. Measurements where speed equals zero were removed, because there were instances where a device remained switched on for several hours while the vehicle was stationary, possibly collecting measurements inside the driver’s house rather than the ambient pollution. Observations where PM2.5 > 500 μg/m3 were deemed outliers and removed, with the cut-off value of 500 chosen after consulting typical PM2.5 ranges in polluted cities (e.g., ref. 63). The processed dataset is publicly available at ref. 64.

Hotspot detection method

Our method for detecting urban PM2.5 hotspots consists of four main steps (Fig. 9). The first step is to collect PM2.5 concentrations data by equipping a fleet of vehicles with mobile PM2.5 sensors. The collected data should be appropriately processed, e.g., to remove outliers, as in Section “Data processing”. However, we do not prescribe the processing stages because the guidelines should be as general as possible, whereas the data processing required depends on the context of the mobile sensing deployment. After the data are collected and processed, the second step is background normalisation, which entails correcting for the hour-to-hour meteorological variations in ambient PM2.5 concentrations. Mobile monitoring studies often normalise for background concentrations by scaling the measured values according to the measurements from a local PM2.5 monitoring station20,65,66. However, in September 2021, Kigali had no public reference PM2.5 monitoring station, and moreover, we want our method to be applicable in other cities with no fixed pollution monitoring apparatus. We therefore propose a background-normalisation procedure that only depends on the mobile sensing data. The raw PM2.5 observations are normalised by selecting a window length xw and subtracting the median from the previous xw minutes of observed PM2.5 concentrations (Eq. (1)), an approach similar to the subtraction of a rolling background value in refs. 59,67,68.

where

xw is an important hyperparameter in our method. A longer window (e.g., xw = 60 min) means more observations and a greater number of different drivers are included in the median calculation, so the subtracted baseline is more robust to outliers and noise. On the other hand, a shorter window (e.g., xw = 1 min) enables normalising for variation at a higher temporal resolution. We compared several different window lengths empirically on the Kigali data (xw = 1, 5, 15, 30, 60 min), and eventually selected xw = 15 min because, when grouping observations into 15-min buckets, the resulting average diurnal profile is smoother than for other choices of xw. Here smoothness is measured as minimising the absolute deviation between measurements in consecutive intervals. While xw = 15 is appropriate for the Kigali data, we stress that the parameter should be recalibrated on future datasets, either through the same empirical procedure or by considering factors such as local meteorology, traffic dynamics, and the temporal coverage of the dataset.

Raw PM2.5 measurements are collected with low-cost sensors attached to a fleet of vehicles. The measurements are normalised by subtracting the rolling 15-min median, which removes the hour-to-hour variation in the ambient PM2.5 concentration. A Gaussian process regression surface is fit to the normalised measurements. Finally, tile-wise hotspot scores are calculated to reveal the most polluted locations in the city.

The third step is to fit a Gaussian process regression model to the spatial extent of the city. As in the general regression setting, the objective in Gaussian process regression is to learn a function f relating a quantity of interest yi to a known quantity xi in the presence of random noise εi:

In our context, i ∈ I indexes an observation from the data, \({{\bf{x}}}_{i}\in {\mathcal{X}}\subset {{\mathbb{R}}}^{2}\) is the vector of latitude and longitude coordinates, yi denotes the normalised PM2.5, and f relates the pair of coordinates to its PM2.5 concentration. The Gaussian process model thus only considers the spatial location of an observation, with the background normalisation procedure designed to enable the direct comparison of observations made at different times throughout the month. In Gaussian process regression, the key assumption is that f has a Gaussian process as prior distribution. At any location x* in the city extent \({\mathcal{X}}\), the Gaussian process regression model thus represents the pollution f(x*) as a probability distribution as opposed to a static value, which we argue is a faithful representation of the real-world dynamics of PM2.5. At any location in an urban environment, the ambient PM2.5 concentration is determined by a multitude of factors such as meteorological conditions, passing vehicles and nearby construction activities, all of which vary in intensity across short time scales. Representing the pollution as a probability distribution rather than a static value quantifies this variability. Additionally, Gaussian process regression outputs spatially-explicit variance estimates as opposed to one single variance estimate for the city, so the model captures the fact that some areas experience a greater variability in pollution levels than others (e.g., a busy intersection versus a rural backstreet).

The fourth and final step is to divide the urban area into a grid of tiles and calculate tile-wise hotspot scores. We consider as hotspots the locations where the pollution levels are frequently higher than the average pollution level across the whole city. This definition is compatible with the fact that pollution sources are dynamic, so any location in a city could theoretically experience high pollution at a given time. Therefore, what makes a location a hotspot is that the pollution is regularly greater than the average for the whole city. We propose ‘hotspot scores’ derived from the Gaussian process model to quantify the hotspots. Formally, for a tile j with a centroid at xj = (latj, lonj), we define the hotspot score h(j) as the estimated posterior probability that f(xj) exceeds the empirical median of normalised PM2.5 for the city, median(y):

The hotspot score at xj quantifies our belief that an observation of the PM2.5 concentration there would exceed the empirical median for the city. For example, a hotspot score of 0.3 means that we expect 30% of noise-free PM2.5 observations to exceed the city-wide median. All quantities are background-normalised, so the hotspot scores exclude the hour-to-hour variation in ambient PM2.5 concentrations and summarise the spatial variability between locations. A common baseline median(y) is used for every tile so that the hotspots are relative to the whole city, as opposed to the window-based approaches discussed in the Introduction. The tile size regulates the granularity of the air quality estimates. Urban air quality studies with gridded observations typically choose a tile length of tens or hundreds of meters43,66,69. We recommend adjusting the tile size according to the sparsity of the observed data, since sampling density has been shown to affect the accuracy of spatial air pollutant estimates65.

Practical implementation

Throughout this work we apply the exponential kernel as the covariance function k:

ℓ is the length-scale parameter which models the ‘spikiness’ of the kernel, and \({\sigma }_{k}^{2}\) is the kernel variance parameter, which are both optimised during model training by gpflow70. Other researchers have typically preferred the squared exponential kernel for modelling PM2.5 concentrations with Gaussian process regression31,35,71. However, during empirical testing on the Kigali dataset, we found that the squared exponential kernel smoothed over the spatial variation in PM2.5 levels, producing near-equal hotspot scores throughout most of the city and then very high hotspot scores at a single location. By contrast, the exponential kernel produced variegated hotspot scores.

As described by Rasmussen and Williams72, ‘One issue with Gaussian process prediction methods is that their basic complexity is \({\mathcal{O}}({n}^{3})\), due to the inversion of a n × n matrix. For large datasets this is prohibitive (in both time and space)’. With mobile sensing datasets typically comprising a large number of observations, fitting a single Gaussian process to all of the mobile sensing observations can be computationally infeasible. Hence we instead apply simple bagging with subsamples of the data73, as detailed in the Gaussian process context by Chen and Ren74. Instead of estimating one spatial PM2.5 distribution for the city extent, we take B random samples of size m < < n from the mobile sensing data and fit a separate model \({\widehat{f}}_{b}\) to each sample b = 1, …, B. Predicted means and variances at a point xi are computed by averaging the B individual predictions according to:

where \(\widehat{{\mu }_{b}}({{\bf{x}}}_{i})\) and \({\widehat{{\sigma }_{b}}}^{2}({{\bf{x}}}_{i})\) are respectively the mean and variance values of f(xi) predicted by the b’th model. However, unlike Chen and Ren74, we do not select observations for the B samples uniformly at random. Instead, we employ a scheme to disproportionately sample from the most polluted and least polluted grid tiles, to ensure that more data is gathered about tiles suspected to be hotspots or coldspots. Our sampling scheme orders the grid tiles according to their median normalised PM2.5 concentration. Then, we specify probabilities phigh and plow and thresholds rhigh and rlow, and proceed to sample observations from the top rhigh proportion of tiles with probability phigh and from the bottom rlow proportion of tiles with a probability proportional to plow. In our experiments we chose phigh = plow = 0.3 and rhigh = rlow = 0.2, meaning observations belonging to the most fifth and the least polluted fifth of tiles are 50% more likely to appear in a bootstrapped sample than the rest of the observations.

Once the B gaussian process regression surfaces have been fit, we predict the mean and variance of f at every tile centroid xj in the grid according to Eqs. (4) and (5). By the marginalisation property of Gaussian processes72, the normalised PM2.5 f(xj) at a tile centroid xj is a random variable with the distribution N(μ(xj), σ2(xj)) which we estimate by \(N(\widehat{\mu }({{\bf{x}}}_{j}),{\widehat{\sigma }}^{2}({{\bf{x}}}_{j}))\). Denoting by median(y) the estimated median of normalised PM2.5 throughout the city, the estimated probability that f(xj) exceeds the city-wide median PM2.5:

thus equals:

where Z ~ N(0, 1) is a standard Gaussian variable. This probability is exactly the hotspot score h(j) reported in this study.

All experiments were run on a machine with a 12th Gen Intel(R) Core i7-1260P CPU (12 cores, 16 processors), 16GB RAM, running Microsoft Windows 11. The code was executed using Python 3.11.7 with version 2.9.1 of package gpflow. We bagged B = 100 models fit to subsets of m = 2000 datapoints in the experiments. The process of fitting the models, predicting the mean and variance across the spatial grid and then combining the results typically took around 3 hours to execute.

Validating the method

In addition to the PM2.5 concentrations data gathered in Kigali, we evaluate our method using another dataset of spatial average PM2.5 concentrations in Beijing, China. Published by Wang et al.43, this dataset consists of estimated seasonal average PM2.5 concentrations at a 30 × 30 m spatial resolution. The authors estimated PM2.5 concentrations by combining the WRF-CMAQ atmospheric dispersion model75 with several data sources, including top-of-atmosphere satellite data, land-use data, and terrain data like elevation above sea level. We evaluate our hotspot-detection method by treating their spatial PM2.5 estimates in Beijing as a ground-truth spatial PM2.5 distribution, then simulating a mobile sensing dataset and applying our hotspot-detection method to the simulated data.

Simulating the mobile sensing PM2.5 measurements began with simulating the vehicle routes. Using road network data from the Open Street Map (OSM), we selected ten thousand pairs of random on-road points within the evaluation area. Every pair of points represents a start and end location of a driver’s journey: \(\{(({\text{lat}}_{s}^{{\text{start}}},{\rm{l}}{\rm{o}}{{\rm{n}}}_{s}^{{\text{start}}}),({\text{lat}}_{s}^{{\text{end}}},{{\text{lon}}}_{s}^{{\text{end}}})){\text{for}}\,s=1,2,\ldots ,10,000\}\). The networkx package in Python was then used to compute the shortest on-road path between every pair of points76. This produces ten thousand on-road routes, which roughly corresponds to sixteen delivery drivers making thirty trips per day for twenty days (20 × 16 × 30 = 9600).

The next step was to generate observation locations and associated timestamps along all the routes. Recall that the mobile sensors measure the PM2.5 concentration once per second. Assuming a constant speed of 30 km/h, this corresponds to one observation every 8.33 m, so observation locations were generated at uniform intervals of 8.33 m along the on-road routes. Every start location was assigned a random timestamp in the period of September 2019, then timestamps were assigned in increments of one second to the subsequent observations within the same journey. This resulted in a total of 2.7 million observation locations of the form (lat, lon, t) for each evaluation area, equivalent to ~750 h of data.

Finally, a PM2.5 measurement was assigned to every (lat, lon, t) tuple according to the following formula:

where

The hourly multiplier term \(h{m}_{{t}_{i}}\) captures the fact that depending on the time of day, a driver passing through the same location can experience drastically different pollution levels due to traffic patterns or meteorological variations. Hourly multipliers were computed using data from the US embassy’s stationary PM2.5 sensor in Beijing. The sensor measures the ambient PM2.5 once every hour, and we converted the embassy measurements to hourly multipliers by dividing each measurement by the overall median of the embassy measurements for September 2019. As an example, an hourly multiplier of 1.2 means that, in a given hour on a given day, the PM2.5 concentration was 20% higher than the overall median for September 2019. By scaling according to the embassy measurements, we introduce realistic temporal variation into the synthetic observations.

Remaining variables in Eq. (6) are stochastic: εi ~ N(0, 1), κi ~ Bern(0.05), and γi ~ Gamma(5, 5). κiγi is a stochastic term that only affects 5% of the measurements, and corrupts them with an additive PM2.5 value drawn from the Gamma(5, 5) distribution. The Gamma(5, 5) distribution has a positive support and a long tail, so this term represents sudden pollution spikes like the exhaust emissions from a passing truck or dust from unpaved roads, a phenomenon observed in our Kigali data and also reported in previous mobile sensing campaigns65. ε is always present and represents random noise, including possible measurement error. These stochastic interferences further complicate the recovery of the spatial PM2.5 hotspots.

Two evaluation areas ~3 × 3 km in size were selected. The first evaluation area is in the East of Beijing and is referred to as ‘CLT’, because the area encompasses a landmark building called the China Life Tower (39°55’26”N, 116°26’22”E). The second evaluation area is in the Southeast of the city, denoted ‘LP’ because it encompasses the Longtan Park (39°52’47”N, 116°26’25”E). Although Wang et al.43 published PM2.5 concentrations estimates for all four seasons, we only used their Autumn estimates.

We address two main questions when evaluating our method on the simulated Beijing data:

-

Do the hotspot scores reflect the spatial profile of average PM2.5 concentrations throughout the city?

-

Are the hotspot scores probabilistically well-calibrated?

To address the first question, we plot the spatial distributions of the hotspot scores and of the gridded average PM2.5 concentrations side by side.

We also compute the Spearman rank correlation coefficient ρ(h, PM2.5) between the hotspot scores h ≔ (h(j))j∈J and the spatial average pollution values, \({\text{PM}}_{2.5}:={({\text{PM}}_{2.5}^{j})}_{j\in J}\):

Here R(h) and R(PM2.5) are the rank vectors of the hotspot scores and the spatial average PM2.5 values, respectively, while the denominator terms are the standard deviations of these rank vectors. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient ρ is a non-parametric measure of correlation which is robust to non-linearity. It is bounded between 1, which means a perfect positive correlation, and −1, which means a perfect negative correlation. The closer ρ is to 1, the better the hotspot scores are at capturing the spatial pollution profile.

To address the second question: recall that the hotspot scores are estimated posterior probabilities for the event {f(xi) > median(y)} (Eq. (3)). In the simulated data, f(xi) is known for every observation xi. Hence we can perform a calibration analysis, comparing the occurrence of the event {f(xi) > median(y)} against the hotspot scores, which are the estimated probabilities of this event. Perfect calibration would mean that in every tile, the hotspot score equals the proportion of observations where the event {f(xi) > median(y)} occurs, which we henceforth call the exceedance proportion.

To perform a calibration analysis, we split the mobile sensing data into a test set, containing observations from six randomly-selected days in September 2019, and a training set, containing the observations from the remaining twenty four days. Hotspot scores are computed using only the training data, then the calibrations are evaluated on the test data. Test observations are grouped into ten uniformly-spaced bins according to the hotspot score of their tile, i.e.,

which enables plotting reliability diagrams to show the actual exceedance proportion among observations in each bin. We also report the Brier score:

which is the average squared error between the hotspot scores and the binary variable bi for whether the i’th observation exceeds the median. Additionally, we report the expected calibration error (ECE):

which is the mean absolute difference between the exceedance proportion and the average hotspot score across the ten bins77.

Calibration regression

As part of the analysis we also evaluate whether a calibration regression can improve the probabilistic calibration. A calibration regression is a model regressing the observed frequencies in the data on the predicted probabilities. It is commonly applied to transform the outputs of a model that predicts probabilities in the supervised learning setting, with the aim to improve the accuracy of the predicted probabilities78,79.

As argued by Dormann80, a calibration regression is not necessary when the goal of the hotspot-detection is merely to rank the tiles by their average pollution, because calibration regression procedures are generally monotone transformations. However, a calibration regression is important when one wants to interpret the hotspot scores as posterior probabilities. In Section “Results” we investigate whether an out-of-the-box isotonic regression transformation improves the calibration78,81. Isotonic regression entails fitting an isotonic (monotonic-increasing) function m to transform the hotspot scores hi into calibrated hotspot scores \({h}_{i}^{{\text{cal}}}\):

Using the sklearn implementation of the isotonic regressor82, we investigate whether this transformation reduces the expected calibration error of the hotspot scores in the simulated data.

Data availability

The collected and processed Kigali data is available at https://zenodo.org/records/15206350. The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide (World Health Organization, 2021).

Xing, Y.-F., Xu, Y.-H., Shi, M.-H. & Lian, Y.-X. The impact of PM2.5 on the human respiratory system. J. Thorac. Dis. 8, E69–74 (2016).

Zhang, D. et al. Air pollution exposure and heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 872, 162191 (2023).

Gutiérrez-Avila, I. et al. Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular mortality associated with acute exposure to PM2.5 in Mexico City. Stroke 49, 1734–1736 (2018).

Stieb, D. M. et al. Associations of pregnancy outcomes and PM2.5 in a National Canadian Study. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 243–249 (2016).

Bowe, B. et al. The 2016 global and national burden of Diabetes Mellitus attributable to PM2.5 air pollution. Lancet Planet. Health 2, e301–e312 (2018).

GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396, 1204–1222 (2020).

Southerland, V. A. et al. Global urban temporal trends in fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and attributable health burdens: estimates from global datasets. Lancet Planet. Health 6, e139–e146 (2022).

Martin, R. V. et al. No one knows which city has the highest concentration of fine particulate matter. Atmos. Environ. X 3, 100040 (2019).

Apte, J. et al. Air inequality: global divergence in urban fine particulate matter trends https://chemrxiv.org/engage/chemrxiv/article-details/60c75932702a9baa0818ce61 (2021).

Wei, J. et al. First close insight into global daily gapless 1 km PM2.5 pollution, variability, and health impact. Nat. Commun. 14, 8349 (2023).

Alvarado, M. J. et al. Evaluating the use of satellite observations to supplement ground-level air quality data in selected cities in low- and middle-income countries. Atmos. Environ. 218, 117016 (2019).

Gao, M., Cao, J. & Seto, E. A distributed network of low-cost continuous reading sensors to measure spatiotemporal variations of PM2.5 in Xi’an, China. Environ. Pollut. 199, 56–65 (2015).

Lu, Y., Giuliano, G. & Habre, R. Estimating hourly PM2.5 concentrations at the neighborhood scale using a low-cost air sensor network: a Los Angeles case study. Environ. Res. 195, 110653 (2021).

Considine, E. M., Reid, C. E., Ogletree, M. R. & Dye, T. Improving accuracy of air pollution exposure measurements: statistical correction of a municipal low-cost airborne particulate matter sensor network. Environ. Pollut. 268, 115833 (2021).

Song, J., Han, K. & Stettler, M. E. J. Deep-maps: machine-learning-based mobile air pollution sensing. IEEE Internet Things J. 8, 7649–7660 (2021).

Song, J. et al. Toward high-performance map-recovery of air pollution using machine learning. ACS EST Eng. 3, 73–85 (2022).

Cummings, L. E., Stewart, J. D., Reist, R., Shakya, K. M. & Kremer, P. Mobile monitoring of air pollution reveals spatial and temporal variation in an urban landscape. Front. Built Environ. 7, 648620 (2021).

Hart, R., Liang, L. & Dong, P. Monitoring, mapping, and modeling spatial-temporal patterns of PM2.5 for improved understanding of air pollution dynamics using portable sensing technologies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 4914 (2020).

Lim, C. C. et al. Mapping urban air quality using mobile sampling with low-cost sensors and machine learning in Seoul, South Korea. Environ. Int. 131, 105022 (2019).

Bousiotis, D. et al. Pinpointing sources of pollution using citizen science and hyperlocal low-cost mobile source apportionment. Environ. Int. 193, 109069 (2024).

Leung, Y. et al. Integration of air pollution data collected by mobile sensors and ground-based stations to derive a spatiotemporal air pollution profile of a city. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 33, 2218–2240 (2019).

Noulas, A. et al. Modeling urban air quality using taxis as sensors. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.11720 (2025).

Li, J. J., Faltings, B., Saukh, O., Hasenfratz, D. & Beutel, J. Sensing the air we breathe — the OpenSense Zurich dataset. Proc. Conf. AAAI Artif. Intell. 26, 323–325 (2021).

Dauchet, L. et al. Short-term exposure to air pollution: associations with lung function and inflammatory markers in non-smoking, healthy adults. Environ. Int. 121, 610–619 (2018).

Orellano, P., Reynoso, J., Quaranta, N., Bardach, A. & Ciapponi, A. Short-term exposure to particulate matter (PM10 and PM2.5), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and ozone (O3) and all-cause and cause-specific mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ. Int. 142, 105876 (2020).

Collado, J. T. et al. Spatiotemporal assessment of PM2.5 exposure of a high-risk occupational group in a Southeast Asian megacity. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 23, 220134 (2023).

Gelfand, A. E. & Schliep, E. M. Spatial statistics and Gaussian processes: a beautiful marriage. Spat. Stat. 18, 86–104 (2016).

Christianson, R. B., Pollyea, R. M. & Gramacy, R. B. Traditional kriging versus modern Gaussian processes for large-scale mining data. Stat. Anal. Data Min. 16, 488–506 (2023).

Oliver, M. A. & Webster, R. A tutorial guide to geostatistics: computing and modelling variograms and kriging. Catena 113, 56–69 (2014).

Stoddart, C. et al. Gaussian processes for monitoring air-quality in Kampala. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.16625 (2023).

Liu, H., Yang, C., Huang, M., Wang, D. & Yoo, C. Modeling of subway indoor air quality using Gaussian process regression. J. Hazard. Mater. 359, 266–273 (2018).

Wang, P. et al. A Gaussian process method with uncertainty quantification for air quality monitoring. Atmosphere 12, 1344 (2021).

Tang, M., Wu, X., Agrawal, P., Pongpaichet, S. & Jain, R. Integration of diverse data sources for spatial PM2.5 data interpolation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 19, 408–417 (2017).

Cheng, Y., Li, X., Li, Z., Jiang, S. & Jiang, X. Fine-grained air quality monitoring based on Gaussian process regression. In International Conference on Neural Information Processing, 126–134, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-12640-1_16 (2014).

Goyal, P., Gulia, S. & Goyal, S. K. Identification of air pollution hotspots in urban areas - an innovative approach using monitored concentrations data. Sci. Total Environ. 798, 149143 (2021).

Bhardwaj, A. et al. Comprehensive monitoring of air pollution hotspots using sparse sensor networks. ACM J. Comput. Sustain. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1145/3748821 (2025).

Zhang, Y., Hannigan, M. & Lv, Q. Air pollution hotspot detection and source feature analysis using cross-domain urban data. In SIGSPATIAL '21: Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Advances in Geographic Information Systems, 592−595 (2021).

Zheng, T., Bergin, M., Wang, G. & Carlson, D. Local PM2.5 hotspot detector at 300 m resolution: a random forest–convolutional neural network joint model jointly trained on satellite images and meteorology. Remote Sens. 13, 1356 (2021).

Getis, A. & Ord, J. K. The analysis of spatial association by use of distance statistics. Geogr. Anal. 24, 189–206 (1992).

Ord, J. K. & Getis, A. Local spatial autocorrelation statistics: distributional issues and an application. Geographical Anal. 27, 286–306 (1995).

Ruidas, D. & Pal, S. C. Potential hotspot modeling and monitoring of PM2.5 concentration for sustainable environmental health in Maharashtra, India. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 8, 98 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. Ultra-high-resolution mapping of ambient fine particulate matter to estimate human exposure in Beijing. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 451 (2023).

Subramanian, R. et al. Air pollution in Kigali, Rwanda: spatial and temporal variability, source contributions, and the impact of car-free sundays. Clean Air J. 30 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346916819_Air_pollution_in_Kigali_Rwanda_spatial_and_temporal_variability_source_contributions_and_the_impact_of_car-free_Sundays Accessed: 2025-03-28 (2020).

Kagabo, A. S. Spatial-Temporal variation of particulate matter less than 2.5 microns (PM2.5) concentrations in Kigali https://www.researchgate.net/publication/343971560_Spatial-Temporal_Variation_of_Particulate_Matter_less_than_25_microns_PM25_concentrations_in_Kigali (2018).

Henninger, S. M. When air quality becomes deleterious—a case study for Kigali, Rwanda. J. Environ. Prot. 04, 1–7 (2013).

OpenStreetMap contributors. Planet dump retrieved from https://planet.osm.org (2017).

Pesaresi, M. et al. Advances on the global human settlement layer by joint assessment of Earth observation and population survey data. Int. J. Digital Earth 17 https://doi.org/10.1080/17538947.2024.2390454 (2024).

Igarashi, J. Digital elevation model (DEM), 10 m resolution, Rwanda. https://geohub.data.undp.org/data/00d5add9be37e465398b081683c3ec03#Info (2024).

Manirakiza, V., Mugabe, L., Nsabimana, A. & Nzayirambaho, M. City profile: Kigali, Rwanda. Environ. Urbanization ASIA 10, 290–307 (2019).

Kloog, I., Ridgway, B., Koutrakis, P., Coull, B. A. & Schwartz, J. D. Long- and short-term exposure to PM2.5 and mortality: using novel exposure models. Epidemiology 24, 555–561 (2013).

Yu, W. et al. Estimates of global mortality burden associated with short-term exposure to fine particulate matter (PM2.5). Lancet Planet. Health 8, e146–e155 (2024).

Hensman, J., Fusi, N. & Lawrence, N. D. Gaussian processes for big data. In UAI'13: Proceedings of the Twenty-Ninth Conference on Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence, 282−290 (2013).

Deisenroth, M. P. & Ng, J. W. Distributed Gaussian processes. In ICML'15: Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Machine Learning, Vol. 37, 1481−1490 (2015).

Kumar, P., Omidvarborna, H., Tiwari, A. & Morawska, L. The nexus between in-car aerosol concentrations, ventilation and the risk of respiratory infection. Environ. Int. 157, 106814 (2021).

Grana, M., Toschi, N., Vicentini, L., Pietroiusti, A. & Magrini, A. Exposure to ultrafine particles in different transport modes in the city of Rome. Environ. Pollut. 228, 201–210 (2017).

Messier, K. P. et al. Mapping air pollution with Google Street View cars: efficient approaches with mobile monitoring and land use regression. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 12563–12572 (2018).

Hofman, J. et al. Opportunistic mobile air quality mapping using sensors on postal service vehicles: from point clouds to actionable insights. Front. Environ. Health 2 https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvh.2023.1232867 (2023).

Brantley, H. L. et al. Mobile air monitoring data-processing strategies and effects on spatial air pollution trends. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 7, 2169–2183 (2014).

Wu, J. et al. Applying land use regression model to estimate spatial variation of PM2.5 in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 22, 7045–7061 (2014).

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Air quality models https://www.epa.gov/scram/air-quality-models (2024).

Baek, B. H. et al. The comprehensive automobile research system (CARS) – a Python-based automobile emissions inventory model. Geosci. Model Dev. 15, 4757–4781 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. Impact of heavy PM2.5 pollution events on mortality in 250 Chinese counties. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 8299–8307 (2022).

Perry, N. et al. Kigali PM2.5 dataset openseneca September 2021. Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15206350 (2025).

Van den Bossche, J. et al. Mobile monitoring for mapping spatial variation in urban air quality: development and validation of a methodology based on an extensive dataset. Atmos. Environ. 105, 148–161 (2015).

Apte, J. S. et al. High-resolution air pollution mapping with Google Street View cars: exploiting big data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 6999–7008 (2017).

Tessum, M. W. et al. Mobile and fixed-site measurements to identify spatial distributions of traffic-related pollution sources in Los Angeles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 2844–2853 (2018).

Bukowiecki, N. et al. A mobile pollutant measurement laboratory-measuring gas phase and aerosol ambient concentrations with high spatial and temporal resolution. Atmos. Environ. 36, 5569–5579 (2002).

Hasenfratz, D. et al. Deriving high-resolution urban air pollution maps using mobile sensor nodes. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 16, 268–285 (2015).

Matthews, A. G. d. G. et al. GPflow: a Gaussian process library using TensorFlow. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 18, 1299–1304 (2017).

Patel, Z. B., Purohit, P., Patel, H. M., Sahni, S. & Batra, N. Accurate and scalable Gaussian processes for fine-grained air quality inference. Proc. Conf. AAAI Artif. Intell. 36, 12080–12088 (2022).

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. K. Regression, 7–32 (The MIT Press, 2005).

Breiman, L. Bagging predictors. Mach. Learn. 24, 123–140 (1996).

Chen, T. & Ren, J. Bagging for Gaussian process regression. Neurocomputing 72, 1605–1610 (2009).

Wong, D. C. et al. WRF-CMAQ two-way coupled system with aerosol feedback: software development and preliminary results. Geosci. Model Dev. 5, 299–312 (2012).

Hagberg, A. A., Schult, D. A. & Swart, P. J. Exploring network structure, dynamics, and function using NetworkX. In Proceedings SciPy,11–15 (2008).

Pakdaman Naeini, M., Cooper, G. & Hauskrecht, M. Obtaining well calibrated probabilities using Bayesian binning. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 29, https://doi.org/10.1609/aaai.v29i1.9602 (2015).

Niculescu-Mizil, A. & Caruana, R. Predicting good probabilities with supervised learning. In Proceedings of the 22nd international conference on Machine learning 625–632 https://doi.org/10.1145/1102351.1102430 (2005).

Zadrozny, B. & Elkan, C. Transforming classifier scores into accurate multiclass probability estimates. In Proceedings of the Eighth ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 694–699 https://doi.org/10.1145/775047.775151 (2002).

Dormann, C. F. Calibration of probability predictions from machine-learning and statistical models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 760–765 (2020).

Barlow, R. E. & Brunk, H. D. The isotonic regression problem and its dual. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 67, 140–147 (1972).

Pedregosa, F. et al. Scikit-learn: machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 12, 2825–2830 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Krzysztof Cybulski and Lukas Graz from the Statistical Consulting team at ETH Zürich for their advice on the methodology. We also thank the following partners for funding the data collection in Kigali: the Wuppertal Institute, UN-Habitat, and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), and the International Climate Protection Initiative (IKI) of the German Ministry of the Environment. Additionally, we thank the following partners who assisted with collecting the data: the University of Rwanda, the City of Kigali, the Urban Electric Mobility Initiative, and Ampersand Rwanda Ltd. Those affiliated with the University of Cambridge acknowledges funding by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council Centre for Doctoral Training in Sensor Technologies and Applications (EP/L015889/1). We thank the Centre for Global Equality (CGE) for its continued support of open-seneca and its involvement in the Urban Pathways project. We thank Yongyue Wang from Tsinghua University for kindly sharing the Beijing data.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.P.: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing - original draft. P.P.P.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft. C.N.C.: Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing - original draft. E.N.: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing - review & editing. S.He.: Data curation, Methodology, Software, Writing - review & editing. L.D.G.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. R.J.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. S.Ho.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing. C.F.: Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Perry, N., Pedersen, P.P., Christensen, C.N. et al. Detecting urban PM2.5 hotspots with mobile sensing and Gaussian process regression. npj Clean Air 1, 38 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00038-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00038-1