Abstract

Dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5) and nitryl chloride (ClNO2) sever as important precursors of nocturnal nitrate, remain poorly measured. In this study, we observed moderate concentrations of N2O5 and ClNO2 in summer Beijing using a chemical ionization mass spectrometer, with ClNO2 being primarily controlled by the uptake of N2O5 onto particulate chloride. We utilized three methods to quantify nitrate formation through daytime photochemical production (NO2 + OH·) and nighttime N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis. Using chloride as a reference for gas/particle partitioning, we found comparable results with the box model that directly determined the N2O5 uptake coefficient and ClNO2 yield. The nocturnal nitrate production rates ranged from 0.46 to 2.27 µg m-3 h-1, on average accounting for 31.3% of the total nitrate production. These results indicate the predominance of photochemical processing over heterogeneous hydrolysis in nitrate formation in summer Beijing, different from findings in cold seasons over China that suggest a more important role for N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis. Compared to direct measurements of N2O5-ClNO2 combined with box model calculations, the chemical transport model slightly overestimated the contributions of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis (34.8%), although it reproduced the increases during periods with high nocturnal nitrate formation. Our study highlights that enhancing the model parametrization, especially considering aerosol composition and seasonal variations, is crucial for more accurate predictions of particulate nitrate levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Particulate nitrate is a major component of atmospheric fine particles (PM2.5) and plays a critical role in atmospheric chemistry1. Since the implementation of emission control measures in China in 2013, nitrate has surpassed sulfate as the dominant secondary inorganic component in PM2.52,3,4. However, current numerical models often overestimate nitrate levels5,6, primarily due to substantial uncertainties in nitrate formation mechanisms. The two main pathways for nitrate formation involve the daytime reaction of NO2 with hydroxyl radical (OH·), and the nocturnal heterogeneous hydrolysis of dinitrogen pentoxide (N2O5). In the latter process, nitryl chloride (ClNO2) is produced when N2O5 undergoes heterogeneous reactions on the surfaces of chlorine-containing aerosols7. ClNO2 rapidly photolyzes after sunrise, releasing chlorine radicals that can further influence atmospheric chemistry8,9,10. While the photochemical pathway involving OH· oxidation of NO2 has been well characterized and integrated into models11, the heterogeneous reaction pathway remains a significant source of uncertainty in nitrate simulations12.

Extensive field studies have demonstrated the substantial reactivity of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis in the troposphere9,13, revealing significant regional and seasonal variations. For example, nitrate formation from this pathway in Utah, USA, was measured at 3.9 µg m-3 day-1, contributing 86% of the total nitrate production during winter14. In the Pearl River Delta, the strong heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 resulted in a peak ClNO2 concentration of 8.3 ppb, which significantly exceeded levels observed in other regions15, accounting for 44–58% of total nitrate formation. The relative contribution of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis varies considerably under different pollution conditions and environmental factors16. For example, it contributed 52% to total nitrate formation on relatively polluted days, but this contribution was negligible on clean days, indicating that N2O5 chemistry plays a more important role in the formation of nitrate during severe haze events. The precise quantification of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis depends on the determination of the N2O5 uptake coefficient. However, uncertainties remain regarding the N2O5 uptake coefficient γ(N2O5), which can vary widely from 0.00002 to 0.117. This variability is influenced by factors such as relative humidity, temperature, aerosol liquid water content, and aerosol compositions18. Similarly, the yield of ClNO2 φ(ClNO2) also shows a significant regional variation19. Although optical instruments that measure N2O5 are widespread, ClNO2 measurements remain limited. This often leads to reliance on fixed or assumed φ(ClNO2) when quantifying nitrate formation. Therefore, to better understand nitrate formation in Beijing, it is essential to conduct concurrent field observations of N2O5 and ClNO2 to derive specific γ(N2O5) and φ(ClNO2) values relevant to this region, which might be achieved through direct measurement of the molecular composition of nighttime nitrate formation using chemical ionization mass spectrometry20.

Several studies have investigated the nighttime formation of nitrate in Beijing. Wang et al.21 observed significantly higher N2O5 yield in suburban Beijing compared to those reported in North America and Europe. This finding is consistent with Fan et al.22, who reported that N2O5 hydrolysis contributed 80% to total nitrate formation in urban Beijing. While these studies indicated nocturnal nitrate formation from N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis is more significant than previously recognized, there are still debates in the literature. For instance, Chen et al.23 found that the photochemical reaction of NO2 with OH· predominates over N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis, accounting for 74-76% of nitrate formation in Beijing. These discrepancies highlight significant uncertainties in the nighttime nitrate production in Beijing, emphasizing the need for further exploration to clarify the relationship between nitrate formation and factors such as pollution levels, precursor concentrations, and meteorological conditions.

In this study, a high-resolution time-of-flight chemical ionization mass spectrometer (ToF-CIMS) is utilized to measure the key molecular components involved in nocturnal nitrate formation, i.e., N2O5 and ClNO2 in Beijing. Our study examines the nighttime reactivity of N2O5-NO3 and their relationships with precursors. The reaction coefficient of N2O5 and the ClNO2 hydrolysis yield are determined using a developed box model. Additionally, the contribution of nighttime N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis to total nitrate formation is quantified through both field observations and chemical transport model simulations.

Results and discussion

Characterization of summertime N2O5 and ClNO2

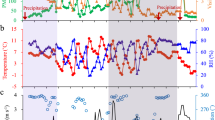

As shown in Fig.1, the concentrations of N2O5 and ClNO2 exhibited significant day-to-day fluctuations during the summer period. The peak N2O5 concentration was observed on 6 June, reaching 729 ppt with a 5-minute average. This value is notably lower than the levels observed in highly aged air masses where N2O5 can reach approximately 7.8 ppb24. Similarly, the peak ClNO2 concentration reached 585.7 ppt, significantly lower than those found at other inland sites, e.g., 2.1 ppb in rural Beijing25 and 2.9 ppb in suburban Beijing21. However, both N2O5 and ClNO2 were considerably higher than those recorded in the nocturnal residual boundary layer at Mt. Tai26. This highlights the more significant role of nighttime N2O5 chemistry in the polluted urban boundary layer, where an abundance of gaseous precursors is present. Consistent with this, the average nitrate radical production rate (PNO3) reached 2.6 ± 1.7 ppb h−1, which exceeds the rates observed in other studies in North China Plain (NCP). For instance, suburban Beijing reported an average of 1.2 ± 0.9 ppb h−1, and Wangdu recorded 1.7 ± 0.6 ppb h−1 21,25. These findings suggest that nocturnal N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis is more active in urban Beijing, possibly due to enhanced atmospheric oxidation during summer, which is linked to high levels of NO2 and O3. For example, O3 concentrations remained high at 19–35 ppb after midnight (Fig. 2). A recent study demonstrated the average nocturnal PNO3 at 1.07 ± 0.38 ppb h−1 in China27, which is significantly higher than values observed at other global sites, e.g., the European Union and the United States, further emphasizing the substantial role of nighttime chemistry in this region.

a NO2, b O3, c N2O5, d NO3−, e Chl and f ClNO2. Mean (circle), median (horizontal line), 25 and 75 percentiles (lower and upper box edges), 10 and 90 percentiles (lower and upper whiskers) are shown for each hour. Also shown are diurnal patterns of mean variables during P1 (in red) and P2 (in blue).

Due to strong photolysis, N2O5 and ClNO2 exhibited prominent diurnal cycles, rapidly forming after sunset and decomposing immediately after sunrise. The afternoon minimum for ClNO2 remained below 5 ppt in this study, which contrasts with a previous campaign finding abnormal persistence of ClNO2 up to 60 ppt in the afternoon at a rural site in NCP28, the cause of which remains unexplained. The diurnal peak of ClNO2 occurred at midnight, 3 hours after the peak of N2O5. This timing is consistent with findings by Wang et al.29 who observed a similar 3 h time lag for peak ClNO2 concentrations in urban Ji’nan. The availability of particulate chloride sources in urban Beijing could potentially limit ClNO2 formation. However, it is more likely that ClNO2 formation is controlled by the uptake and reaction of N2O5 on the surface of particulate chloride, rather than by the gaseous precursors themselves, given that NO2 and O3 remain high during nighttime. This observation contrasts with findings in other regions, such as the United Kingdom, where precursor gases were found to be the dominant factor in ClNO2 formation30.

To further investigate the relationship between N2O5, ClNO2, and their precursors, the sampling period was divided into two phases based on changes in aerosol compositions, namely P1 (31 May–8 June) and P2 (9–23 June). Figure 3 shows that the PM1 mass significantly increased from P1 to P2, particularly at night (e.g., from 23.7 to 40.2 μg m−3). Notably, the composition of PM1 also showed significant differences between the two phases. While the mass concentrations of organics remained comparable across both phases, the SIA showed a significant increase from P1 to P2. This was likely driven by higher RH and surface area density during P2. The nitrate concentration exhibited the largest increase, rising by a factor of 7 from P1 to P2, with its contribution to total PM1 increasing from 7% to 28%. A notable observation was the much larger nighttime enhancement of nitrate compared to the daytime, suggesting a stronger formation of particulate nitrate during P2, possibly due to N2O5 heterogeneous reaction. In parallel, ClNO2 formation was also more pronounced during P2. This is further supported by the higher ClNO2/N2O5 ratio in P2 compared to P1, e.g., 2.8 vs. 0.3, which can likely be attributed to the high aerosol liquid water content that facilitates the conversion of N2O5 to ClNO2 under conditions of high aerosol loadings. Distinct diurnal patterns for particulate nitrate between P1 and P2 also support this hypothesis (Fig. 2). In P1, nitrate concentration reached its peak at 11:00–12:00 due to photochemical production after sunrise, but it decreased to a minimum by 17:00-18:00 as a result of evaporation losses31,32. In contrast, nitrate concentration rapidly accumulated after sunset during P2 and reached its peak before sunrise. Notably, the diurnal patterns of particulate nitrate closely aligned with those of ClNO2, further validating the intense N2O5 heterogeneous uptake by aerosols during P215.

Direct and indirect nocturnal loss of N2O5

The steady-state of N2O5 is typically reached within about 30 minutes during the summer21. To estimate the N2O5 steady-state lifetime, we used data points collected 0.5 h after sunset for calculation. In fact, the close correlation (R2 = 0.99) between the calculated N2O5 lifetime and those simulated by the box model further validated the rationale behind this estimation in this study. As shown in Fig. 4, the calculated τ(N2O5)−1 ranged from 0.0006 s−1 to 0.085 s−1 throughout the campaign, with an average of 1.7 ± 1.6 × 10−2 s−1. These rapid N2O5 loss rates are consistent with those reported in previous field campaigns in the NCP, for example, 1.3 × 10−2 s−1 in Wangdu and (1.3–1.4) × 10−2 s−1 at Mt. Tai25,26. However, these values are much higher than those observed in Southern China and the United States24, likely due to the more intense direct and indirect loss of N2O5 associated with high aerosol loadings and precursor concentrations in Northern China.

The box model predicted an average N2O5 direct loss rate of 1.4 ± 1.5 × 10−2 s−1 during the campaign. The significant fluctuations in N2O5 direct loss rates highlight the large variability of N2O5 chemistry, which is significantly influenced by changes in meteorological conditions. For instance, high RH promotes the hygroscopic growth of aerosols and enhances the heterogeneous uptake process, leading to the efficient removal of N2O5. These direct loss rates were one order of magnitude higher than those observed in suburban NCP21, further indicating more active N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis in urban areas. Indeed, Wang et al.16 also found fast direct loss of N2O5 in urban Beijing, ranging from 0.0135 to 0.0057 s−1. In contrast, the reaction rate constant for NO3 radical with VOCs was 0.018 s−1, resulting in an average N2O5 indirect loss rate of 2.2 ± 1.4 × 10−3 s−1. These results indicate that the nighttime reactivity of N2O5-NO3 in urban Beijing is significantly stronger than in other regions, which is likely due to enhanced VOCs emissions and aerosol loadings, which facilitate the loss of both NO3 and N2O5.

The averaged τ(N2O5)−1 was 7.2 ± 2.7 × 10−3 s-1 and 2.2 ± 1.9 × 10−2 s-1 during P1 and P2, respectively, confirming that N2O5 chemistry was more active during P2. This higher activity during P2 explains the larger formation of nitrate and ClNO2 in this phase, primarily due to N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis. Correspondingly, the N2O5 direct loss rate is five times higher in P2 than P1, e.g., 1.9 ± 1.7 × 10−2 s−1 vs. 3.8 ± 2.5 × 10−3 s−1. Compared to the N2O5 indirect loss via NO3 radicals, the direct loss pathway dominated the total nocturnal sink of N2O5, on average accounting for 86%. The contributions of N2O5 direct loss varied significantly between different periods, for example, 55% at P1 and 92% at P2. This variation is due to the favorable conditions for N2O5 heterogeneous reactions in P2, characterized by high aerosol loading and high RH. The proportion of N2O5 direct loss observed in this study was notably higher than values reported in previous studies from summer 2016 (24%) and 2017 (7–33%) in Beijing21,33. The considerable variations across different years are primarily driven by changes in the concentrations of precursors, N2O5, VOCs and PM loadings. The uncertainty inherent in various methods used to estimate N2O5 uptake coefficients, e.g., box model and steady-state assumptions, also contributes to a relatively small differences in the results. In contrast, Wang et al.16 found that the nocturnal N2O5 loss was primarily due to heterogeneous hydrolysis in autumn 2017, contributing 69–99% of the total N2O5 loss, suggesting significant seasonal variations in the processes governing N2O5 loss. The dramatic variations in N2O5 loss observed across different studies emphasize the uncertainty in quantifying nocturnal N2O5 loss due to the limited sampling periods and varying conditions. These findings highlight the need for long-term measurements of N2O5 and ClNO2 at different locations. Nevertheless, the increased influence of N2O5 direct loss from 2016 to 2018 might indicate the growing significance of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis in the nocturnal nitrate formation over the years. This is consistent with the increased nighttime oxidation in China between 2014 and 201927, which has not only led to a greater contribution of N2O5 chemistry to wintertime haze34, but also to summer haze formation.

Practical quantification method using gas/particle partitioning mechanisms

Previous field campaigns have observed similar variations in the gas-to-particle partitioning coefficients of ammonium nitrate and ammonium chloride35,36, which were found to be anti-correlated with RH and positively correlated with temperature. The similar mechanisms enable us to estimate particulate nitrate formation from different pathways using chloride as a reference. This practical method is based on two key assumptions: (1) both ammonium nitrate and chloride are semi-volatile and share similar gas/particle partitioning mechanisms; (2) the diurnal cycle of chloride is mainly driven by gas-particle partitioning with minimal contribution from primary sources. During the summertime, primary emissions of chloride such as coal combustion and biomass burning are negligible in urban Beijing, making the assumption (2) valid. However, it is important to note that this quick estimation method is not applicable in locations or seasons with significant primary emissions, such as during winter when coal combustion is more prevalent. By comparing the diurnal cycles of nitrate and chloride, we can estimate the net nitrate that is formed secondarily through either photochemical production or heterogeneous reactions. The nitrate associated with gas-particle partitioning can be calculated using the following equation,

where a is the slope of the linear regression, and b is the intercept,

To account for the diurnal variation, we scale the maximum and minimum of chloride concentrations (Chlmax and Chlmin) to the corresponding nitrate concentrations (\({{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}}_{\max }\) and \({{\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{3}}_{\min }\)) in Eq. (1). This gives the following expression,

Therefore, the net formation of nitrate (NO3, net) can be calculated by subtracting the NO3, G/P from total nitrate, which represents the secondary productions,

As shown in Fig. 5, the total net nitrate formation was 13.7 µg m−3 during the daytime, while during the nighttime, it was dominated by N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis, contributing 12.4 µg m−3. These results indicate that photochemical production plays a slightly more significant role in nitrate formation than heterogeneous reactions during this period, with contributions of 52.5% and 47.5%, respectively. This practical method allows for the rapid quantification of nitrate from different formation pathways by measuring only the aerosol components of nitrate and chloride, thereby reducing the measurement costs associated with earlier methods that rely on oxygen isotope observations or chemical ionization mass spectrometers. Considering the widespread use of ion chromatography for aerosol composition measurements at many sites, our method could be broadly applied.

Box model method using N2O5 uptake coefficient and ClNO2 yield

The predicted uptake coefficients of N2O5 were in the range of 6.8 × 10−4-0.096, with a mean value of 0.06. These values consistently fall within the range summarized by extensive field campaigns and laboratory studies (0.0001–0.1)17. We also determined the ClNO2 yields using the box model, which ranged from 1.0 × 10−4 to 0.48, with an average of 0.01. These yields are notably lower than those observed in aircraft and ground measurements19, suggesting a relatively high N2O5 uptake coefficient but a low ClNO2 yield in urban Beijing. This phenomenon is not unique, as it is also observed in urban Ji’nan due to suppressed chloride activation in the atmosphere29. Despite the generally low φ(ClNO2), we found that high RH and aerosol loading during P2 increased the ClNO2 yield, with an average of 0.0035 during P1 and 0.016 during P2. This resulted in higher ClNO2 levels in P2 compared to P1, e.g., 105.5 vs 37.4 ppt.

Gaseous HNO3 is primarily formed through the reaction of NO2 with OH· during the daytime, and thus the rate of nitrate formation from this process can be estimated by integrating the product of \(\int \left[{{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\right]\times [{\rm{OH}}]{\rm{dt}}\) over time. In this study, approximately 84% of the gas-phase HNO3 was estimated to partition into particulate nitrate, as calculated using thermodynamic ISORROPIA II models. Since direct measurements of OH radicals were unavailable, OH·concentrations were estimated based on the WRF-Chem simulations for the same period in Beijing37. The estimated OH radical concentrations ranged from 3.7 to 9.7 × 106 molecules cm−3 during the daytime, which are comparable to the values observed in other field campaigns in NCP38. As a result, the nitrate formation rate during the daytime was calculated to be 0.58–2.51 µg m−3 h−1, with a mean of 1.47 µg m−3 h−1. The photochemical reaction rate for nitrate was approximately 30% higher during P1 than P2, due to a higher mixing ratio of NO2 and stronger solar radiation. Considering that the parameters used for nitrate formation rate via photochemical production are from multiple sources, the total uncertainty for the photochemical reaction rate of nitrate is calculated to be 30%, with a 10% for NO2 measurement, a 20% for OH radical estimation and 20% for the ISORROPIA II model inputs. It is important to note that the total accumulated nitrate during the daytime was 8.7–37.7 µg m-3, consistent with the practical estimation in Section 3.3.1, further validating both methods.

For nocturnal nitrate formation via N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis, the average nitrate formation rate was determined to be 0.46–2.27 µg m−3 h−1 (Fig. S3). Figure 6 illustrates the averaged nitrate formation rates from different pathways during P1 and P2, respectively. The higher production rate from N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis during P2 compared to P1 (1.28 vs. 0.87 µg m−3 h−1) supports our earlier conclusion that the increased formation of nitrate and ClNO2 is linked to more active N2O5 heterogeneous reactions. Despite this, particulate nitrate formation was still predominantly driven by photochemical processes rather than heterogeneous hydrolysis. While P1 was characterized by prominent nitrate production from photochemical reaction, the rates for the two formation pathways were comparable during P2. On average, the nocturnal nitrate formation accounted for 31.3% of the total nitrate production over the entire day (Fig. 6), ranging from 10.9% to 66.9% during the campaign. These proportions were lower than the 52% reported by Wang et al.16 in autumn, and also lower than those observed during wintertime in the United States (52-85%)14. Indeed, except for Chen et al.23 finding less than 30% nitrate produced from N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis, extensive studies revealed comparable or slightly more important role of nocturnal N2O5 chemistry in particulate nitrate formation in cold season over China (Fig. S1). One possible explanation for this seasonal difference is the frequent occurrence of haze events during the cold season, along with lower temperature, and longer nighttime periods, which favor N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis.

“Obs” refers to direct measurements of N2O5 and ClNO2 combined with box model calculations (dark blue), as well as the NO2 + OH radical reaction (bright blue). “Sim” represents GEOS-Chem simulations for N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis from the grid point corresponding to our observation site. The pie charts refer to the observed average contributions of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis and the NO2 + OH radical reaction to total nitrate formation.

GEOS-Chem simulations for contribution of N2O5 heterogeneous uptake

We further conducted model simulations and compare the results with direct measurements combined with box model calculations, to assess the performance of the current N2O5 uptake coefficient parameterization in modeling nocturnal nitrate formation pathways. The GEOS-Chem demonstrated acceptable performance in simulating SIA species (Fig. S2), with correlation coefficients (r2) ranging from 0.4 to 0.61. In particular, the model effectively reproduced the daily variations of particulate nitrate, and captured the significant increase from P1 to P2. However, the model tended to overestimate the nitrate concentrations overall, with a linear slope of 1.63 between simulated and observed values. The simulated average nitrate formation rate during the entire study period was generally consistent with the results from the box model, although the former was slightly higher (0.93 vs. 1.12 µg m−3 h−1, Fig. 6). On average, the heterogenous hydrolysis pathway contributed 34.8% to the total simulated nitrate. Notably, the contribution of this pathway was found to increase to up to 42.9% under more polluted conditions during P2, indicating the growing importance of N2O5 chemistry during severe haze events. These results indicated the consistency between box model and GEOC-Chem simulations in reproducing nitrate formation pathways.

Additionally, we expanded the model simulation to assess nitrate formation across the broader NCP region, evaluating the spatial distribution of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis contributions to total nitrate. As shown in Fig. 7, the high contributions of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis during P2 were mainly distributed in the northeast of Shanxi province, north of Shandong province and south of Hebei province, but generally less than 40%. These findings suggest that, compared to direct measurements, the chemical transport model simulations consistently showed higher contributions from heterogenous reaction pathway to nitrate formation. These results highlight the need for more sophisticated parameterization schemes in future nitrate simulations. Specifically, it is crucial to consider the impact of aerosol composition on the hydrolysis process, as well as the varying conditions and seasons, to further improve the accuracy of model predictions.

Methods

Measurements and instruments

A summer field campaign was conducted at the Institute of Atmospheric Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (39◦58’28”N, 116◦22’16”E; ASL: 49 m) in urban Beijing39, from 23 May to 24 June, 2018, during a period characterized by strong photochemical production. This site has been extensively reported, and it is located near residential areas and traffic roads, with no factory sources in the vicinity39. The study employed an Aerodyne ToF-CIMS using iodide ion (I-) as the reagent to detect key molecular components involved in nocturnal nitrate formation, specifically N2O5 and ClNO2. Details of the instrument have been provided by Zhou et al.33 and Zhou et al.40. In Brief, iodide was generated by passing ultra-high-purity (UHP) nitrogen gas (99.999%) through a heated iodide methane permeation tube (VICI, 170-015-4600-U50). The iodide ions were then ionized by a soft X-ray ionization source (Tofwerk AG, type P), and the resulting ions underwent adduct reactions with ambient molecular species in the ion-molecule reaction (IMR) chamber, which were subsequently detected by the instrument. To ensure accuracy, background measurements were performed daily by introducing UHP nitrogen into the inlet.

In parallel, aerosol compositions of particulate matter less than 1 µm (PM1) were measured using an Aerodyne high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer and an Aethalometer. These instruments provided data on the concentrations of organics (Org), sulfate (SO4), nitrate (NO3), ammonium (NH4), chloride (Chl), and black carbon (BC)41. The concentrations of gaseous precursors (e.g., NO2, O3) were measured using a series of thermal gas analyzers. NH3 was measured using a Picarro NH3 analyzer at a time resolution of 1 min. Particle number concentrations within the range of 11–550 nm were measured using a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS).

The ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic model42 was used to calculate the aerosol liquid water content and the gas-particle partitioning coefficient for gas phase HNO3 into particulate nitrate. The model inputs included NH3 and inorganic species of PM1 by using forward mode, indicating that the absence of gas phase HNO3 measurement as input could slightly affect the partitioning results of nitrate. It is important to note that the aerosol liquid water content associated with organics accounted for a small proportion (less than 5%), which indicates that the only considering inorganics species in the ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic model would not introduce significant bias in the results.

Quantifying N2O5 and ClNO2

The ToF-CIMS data were processed using the standard software Tofware. N2O5 and ClNO2 are identified at m/z 235 and m/z 208 as I•N2O5− and I•ClNO2−, respectively43,44. To account for the fluctuations of the reagent ion concentration due to variations in ambient conditions, the raw signals of N2O5 and ClNO2 were normalized to iodide after subtracting the instrument background.

The calibration for N2O5 was performed post-campaign. Solid N2O5 stored at low temperatures was diffused into a flow of zero air, which was simultaneously directed through both the ToF-CIMS and a NOx analyzer. N2O5 gradients were generated by adjusting the flow rate of zero air, and the resulting data a strong correlation (R2 = 0.99) between the N2O5 raw signal measured by ToF-CIMS and the N2O5 mixing ratio measured by the NOx analyzer with a sensitivity of 2.0 cps/ppt. The sensitivity ratio for different molecules in the instrument is relatively stable under consistent voltage settings, allowing the same calibration to be applied to ClNO2 measurements, as previous results from summer 2017 indicated similar sensitivity between N2O5 and ClNO233. It is important to note that the sensitivity of the instrument to N2O5 and ClNO2 is significantly influenced by the water vapor pressure in the IMR chamber45,46. Water vapor promotes the binding of these molecules with iodide, which increases their sensitivity43. However, the sensitivity obtained in this study was slightly lower than the true value due to the relatively low humidity during the calibration experiments, introducing a small degree of uncertainty in the quantification of N2O5 and ClNO2. Overall, the measurement uncertainties for N2O5 and ClNO2, as determined using ToF-CIMS, were 17%.

Box model

The heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 during the nighttime involves several key reactions. Initially, NO2 reacts with O3 to form NO3, with the reaction rate constant (k1) being temperature-dependent. The NO3 radical undergoes rapid photolysis after sunrise, but it can also react with NO2 to form N2O5 at night. N2O5 can thermally decompose back into NO3 and NO2, with the reversible reaction rate Keq is temperature-dependent. The recommended values for k1 and Keq are adopted from Atkinson et al.47 and Brown and Stutz48, respectively. The nighttime NO3 radical concentration can be determined through the equilibrium between N2O5 and NO3, which is rapidly established after sunset49. N2O5 is primarily removed through two pathways: indirect removal via the reaction of NO3 with NO or VOCs, and direct removal through heterogeneous hydrolysis on surfaces containing water or chloride aerosols (reactions 5 and 6). These reactions can be combined into equation (7), where \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) represents the uptake coefficient for N2O5 heterogeneous reaction, and φ is the yield of ClNO2. When N2O5 hydrolysis reaction is not limited by gas diffusion, \({{k}}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) can be simplified as shown in equation (8)50,51,

where c is the average molecular velocity of N2O5, and Sa is the aerosol surface density calculated from particle number concentrations.

During the nighttime, only O3, NO2, NO3, N2O5, and ClNO2 are considered to participate in reactions (1)−(4) and reaction (7). The processes of emissions, depositions and transport within the planetary boundary layer were not accounted for in the zero-dimensional box model. Therefore, the temporal evolution of these species is described by the differential equations (10)−(13), where s(t) represents the proportion of NO3 radical that generates N2O552, which changes over time between 0 and 1.

For the calculation of \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\), a time resolution of 5 min and a 10-s time step were used with the fixed simulation time ranging from 19:45 to 04:45 each day. The observed concentrations of NO2 and O3 were input as initial concentrations for the nighttime reactions. The model iteratively adjusted \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) until the model output agrees with the observation of N2O5 within 1%, while \({\rm{\varphi }}\) is determined as the ratio of observed ClNO2 to integrated N2O5. As a result, 1979 groups of \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) and φ were obtained from simulations in which only N2O5 levels greater than 5 ppt were used for calculations. Due to the absence of VOCs measurement during this campaign, \({k}_{{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}}\) was estimated from based on previous observations taken at the same site in summer 2017, yielding an average value of 0.018 s-1. Considering the negligible effect of \({k}_{{{\rm{NO}}}_{3}}\) on \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\)23, the lack of VOCs measurement introduces only a small uncertainty in this study. Considering the measurement uncertainties of 20% for NO2 and O3, and 17% for N2O5 and ClNO2, the uncertainties propagated into the box model following the sum of the squares of the individual uncertainties. As a result, the calculated uncertainties for \({k}_{{{\rm{N}}}_{2}{{\rm{O}}}_{5}}\) and \({\rm{\varphi }}\) were found to be 33% and 37%, respectively

Model simulations

The GEOS-Chem model version 14.5.1 was utilized to simulate the aerosol compositions of PM2.5 in a nested grid over East Asian, with a horizontal° resolution of 0.5° × 0.625°. Numerous previous studies have demonstrated consistent performance between GEOS-Chem simulations and observations of SIA species53,54,55. The meteorological fields for GEOS-Chem were driven by the NASA Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). Monthly anthropogenic emissions over China were sourced from the MEIC inventory for 2018 (MEICv1.4), while emissions for other Asian countries were derived from CEDSv2. The simulation period spanned from May 1 to July 1, with the first week serving as a spin-up to minimize the impact of initial and boundary conditions. For sulfate simulation, Geos-Chem v14.5.1 incorporated four heterogeneous sulfate formation mechanisms parametrized by Shao et al.55, in addition to the gas-phase reaction of SO2 with OH and aqueous-phase in cloud droplet. The ISORROPIA-II thermodynamic equilibrium model was used to calculate the sulfate-nitrate-ammonium system, assuming that particles are in the liquid phase. In GEOS-Chem, HNO3 formation takes place through the gas-phase reaction of NO2 with OH, the oxidation of VOCs by NO3, and the hydrolysis of N2O5. The reactive uptake coefficient of N2O5 was updated in GEOS-Chem v14.5.1, adopting the parameterization of Bertram and Thornton56 for nitrate-sulfate-ammonium aerosol, set to 1 × 10−4 or 1 × 10−3 for organic aerosols depending on the RH. The branching ratio for the heterogeneous partitioning of N2O5 into HNO3 and ClNO2 was established at 1.

Data availability

The data are available upon request from the corresponding author Yele Sun (sunyele@mail.iap.ac.cn).

References

Huang, R. J. et al. High secondary aerosol contribution to particulate pollution during haze events in China. Nature 514, 218–222 (2014).

Zhou, W. et al. Response of aerosol chemistry to clean air action in Beijing, China: Insights from two-year ACSM measurements and model simulations. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113345 (2019).

Xu, W. et al. Changes in aerosol chemistry from 2014 to 2016 in winter in Beijing: insights from high resolution aerosol mass spectrometry. J. Geophys. Res-Atmos. 124, 1132–1147 (2019).

Wen, L. et al. Summertime fine particulate nitrate pollution in the North China Plain: increasing trends, formation mechanisms and implications for control policy. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11261–11275 (2018).

Chen, D., Liu, Z., Fast, J. & Ban, J. Simulations of sulfate–nitrate–ammonium (SNA) aerosols during the extreme haze events over northern China in October 2014. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 10707–10724 (2016).

Zheng, B. et al. Heterogeneous chemistry: a mechanism missing in current models to explain secondary inorganic aerosol formation during the January 2013 haze episode in North China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 2031–2049 (2015).

Finlayson-Pitts, B. J., Ezell, M. J. & Pitts, J. N. Formation of chemically active chlorine compounds by reactions of atmospheric NaCl particles with gaseous N2O5 and ClONO2. Nature 337, 241–244 (1989).

Thornton, J. A. et al. A large atomic chlorine source inferred from mid-continental reactive nitrogen chemistry. Nature 464, 271–274 (2010).

Osthoff, H. D. et al. High levels of nitryl chloride in the polluted subtropical marine boundary layer. Nat. Geosci. 1, 324–328 (2008).

Wang, T. et al. Observations of nitryl chloride and modeling its source and effect on ozone in the planetary boundary layer of southern China. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 121, 2476–2489 (2016).

Zaveri, R. A. & Peters, L. K. A new lumped structure photochemical mechanism for large-scale applications. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 104, 30387–30415 (1999).

Macintyre, H. L. & Evans, M. J. Sensitivity of a global model to the uptake of N2O5 by tropospheric aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 7409–7414 (2010).

Brown, S. S. et al. Reactive uptake coefficients for N2O5 determined from aircraft measurements during the Second Texas Air Quality Study: Comparison to current model parameterizations. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D00F10 (2009).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. On the contribution of nocturnal heterogeneous reactive nitrogen chemistry to particulate matter formation during wintertime pollution events in Northern Utah. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 9287–9308 (2019).

Yun, H. et al. Nitrate formation from heterogeneous uptake of dinitrogen pentoxide during a severe winter haze in southern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 17515–17527 (2018).

Wang, H. et al. High N2O5 concentrations observed in urban beijing: implications of a large nitrate formation pathway. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 4, 416–420 (2017).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. Heterogeneous N2O5 uptake during winter: aircraft measurements during the 2015 winter campaign and critical evaluation of current parameterizations. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 123, 4345–4372 (2018).

Kolb, C. E. et al. An overview of current issues in the uptake of atmospheric trace gases by aerosols and clouds. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 10, 10561–10605 (2010).

McDuffie, E. E. et al. ClNO2 Yields from aircraft measurements during the 2015 WINTER Campaign and Critical Evaluation of the Current Parameterization. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 123, 12,994–913,015 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Atmospheric organic aerosols: online molecular characterization and environmental impacts. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 305 (2025).

Wang, H. et al. Efficient N2O5 uptake and NO3 oxidation in the outflow of urban Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 9705–9721 (2018).

Fan, M.-Y. et al. Important role of NO3 radical to nitrate formation aloft in urban Beijing: insights from triple oxygen isotopes measured at the tower. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 6870–6879 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Field determination of nitrate formation pathway in winter Beijing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 54, 9243–9253 (2020).

Brown, S. S. et al. Nighttime chemistry at a high altitude site above Hong Kong. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 121, 2457–2475 (2016).

Tham, Y. J. et al. Significant concentrations of nitryl chloride sustained in the morning: investigations of the causes and impacts on ozone production in a polluted region of northern China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 14959–14977 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Fast heterogeneous N2O5 uptake and ClNO2 production in power plant and industrial plumes observed in the nocturnal residual layer over the North China Plain. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 12361–12378 (2017).

Wang, H. et al. Increased night-time oxidation over China despite widespread decrease across the globe. Nat. Geosci. 16, 217–223 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. High levels of daytime molecular chlorine and nitryl chloride at a rural site on the North China Plain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 51, 9588–9595 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. Observations of N2O5 and ClNO2 at a polluted urban surface site in North China: High N2O5 uptake coefficients and low ClNO2 product yields. Atmos. Environ. 156, 125–134 (2017).

Sommariva, R. et al. Seasonal and geographical variability of nitryl chloride and its precursors in Northern Europe. Atmos. Sci. Lett. 19, e844 (2018).

Sun, Y. et al. Aerosol characterization over the North China Plain: Haze life cycle and biomass burning impacts in summer. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 121, 2508–2521 (2016).

Hu, M. et al. Acidic gases, ammonia and water-soluble ions in PM2.5 at a coastal site in the Pearl River Delta, China. Atmos. Environ. 42, 6310–6320 (2008).

Zhou, W. et al. Production of N2O5 and ClNO2 in summer in urban Beijing, China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11581–11597 (2018).

Yan, C. et al. Increasing contribution of nighttime nitrogen chemistry to wintertime haze formation in Beijing observed during COVID-19 lockdowns. Nat. Geosci. 16, 975–981 (2023).

Du, H. et al. Insights into ammonium particle-to-gas conversion: non-sulfate ammonium coupling with nitrate and chloride. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 10, 589–595 (2010).

Ianniello, A. et al. Chemical characteristics of inorganic ammonium salts in PM2.5 in the atmosphere of Beijing (China). Atmos. Chem. Phys. 11, 10803–10822 (2011).

Zhang, Z. et al. Simulated phase state and viscosity of secondary organic aerosols over China. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 24, 4809–4826 (2024).

Tan, Z. et al. Radical chemistry at a rural site (Wangdu) in the North China Plain: observation and model calculations of OH, HO2 and RO2 radicals. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 17, 663–690 (2017).

Sun, Y. L. et al. Long-term real-time measurements of aerosol particle composition in Beijing, China: seasonal variations, meteorological effects, and source analysis. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 15, 10149–10165 (2015).

Zhou, W. et al. Molecular characterization of gaseous organic acids and nitrogen-containing compounds from crop straw and wood burning. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 129, e2023JD040568 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Primary and secondary aerosols in Beijing in winter: sources, variations and processes. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 16, 8309–8329 (2016).

Fountoukis, C. & Nenes, A. ISORROPIA II: a computationally efficient thermodynamic equilibrium model for K+-Ca2+-Mg2+–NH4+–Na+–SO42-–NO3-–Cl-–H2O aerosols. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 7, 4639–4659 (2007).

Kercher, J. P., Riedel, T. P. & Thornton, J. A. Chlorine activation by N2O5: simultaneous, in situ detection of ClNO2 and N2O5 by chemical ionization mass spectrometry. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2, 193–204 (2009).

Slusher, D. L., Huey, L. G., Tanner, D. J., Flocke, F. M. & Roberts, J. M. A. thermal dissociation–chemical ionization mass spectrometry (TD-CIMS) technique for the simultaneous measurement of peroxyacyl nitrates and dinitrogen pentoxide. J. Geophys. Res. 109, D19315 (2004).

Lopez-Hilfiker, F. D. et al. Constraining the sensitivity of iodide adduct chemical ionization mass spectrometry to multifunctional organic molecules using the collision limit and thermodynamic stability of iodide ion adducts. Atmo. Meas. Tech. 9, 1505–1512 (2016).

Lee, B. H. et al. An iodide-adduct high-resolution time-of-flight chemical-ionization mass spectrometer: application to atmospheric inorganic and organic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 6309–6317 (2014).

Atkinson, R. et al. Evaluated kinetic and photochemical data for atmospheric chemistry: Volume I – gas phase reactions of Ox, HOx, NOx and SOx species. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 4, 161–1738 (2004).

Brown, S. S. & Stutz, J. Nighttime radical observations and chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6405–6447 (2012).

Brown, S. S. et al. Nitrogen, Aerosol Composition, and Halogens on a Tall Tower (NACHTT): Overview of a wintertime air chemistry field study in the front range urban corridor of Colorado. J. Geophys. Res. - Atmos. 118, 8067–8085 (2013).

Riemer, N. et al. Impact of the heterogeneous hydrolysis of N2O5 on chemistry and nitrate aerosol formation in the lower troposphere under photosmog conditions. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4144 (2003).

Dentener, F. J. & Crutzen, P. J. Reaction of N2O5 on tropospheric aerosols: Impact on the global distributions of NOx, O3, and OH. J. Geophys. Res. 98, 7149–7163 (1993).

Wagner, N. L. et al. N2O5 uptake coefficients and nocturnal NO2 removal rates determined from ambient wintertime measurements. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 118, 9331–9350 (2013).

Zhai, S. et al. Control of particulate nitrate air pollution in China. Nat. Geosci. 14, 389–395 (2021).

Shah, V. et al. Chemical feedbacks weaken the wintertime response of particulate sulfate and nitrate to emissions reductions over the eastern United States. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 115, 8110–8115 (2018).

Shao, J. et al. Heterogeneous sulfate aerosol formation mechanisms during wintertime Chinese haze events: air quality model assessment using observations of sulfate oxygen isotopes in Beijing. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 6107–6123 (2019).

Bertram, T. H. & Thornton, J. A. Toward a general parameterization of N2O5 reactivity on aqueous particles: the competing effects of particle liquid water, nitrate and chloride. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 8351–8363 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate Prof. Shixian Zhai and Dr. Zheng Yu from the Chinese University of Hong Kong for providing the GEOS-Chem simulation results. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42305113, 42207133), and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB0760200). We thank the technical support of the National Large Scientific and Technological Infrastructure “Earth System Numerical Simulation Facility” (https://cstr.cn/31134.02.EL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.Z. and Y.-L.S wrote the paper. H.-Y.D. performed the model simulations. M.-Y.L. conducted the calibration. W.Z., W.-Q.X., J.Z., C.-H.X, Q.-Q.W. performed the measurements. W.Z., H.-Y.D, M.-Y.L., W.-Q.X., J.Z., C.-H.X, Q.-Q.W., Z.-J.Z, Z.-Q.Z., and Y.-L.S. analyzed the data. J.L., W.-G.W., Z.-F.W and Y.-L.S. commented and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, W., Du, H., Liu, M. et al. Role of N2O5 heterogeneous hydrolysis in summer nitrate formation in Beijing: insights from direct measurements and model simulations. npj Clean Air 1, 40 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00039-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00039-0