Abstract

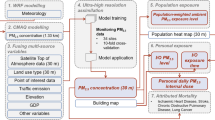

Wildland and wildland–urban-interface (WUI) fires substantially elevate fine particulate matter (PM2.5) concentrations in surrounding communities. Portable high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) purifiers are widely recommended to reduce indoor PM2.5 exposure during such events, yet this guidance largely derives from studies of traffic exhaust, secondhand smoke, or indoor sources, rather than real-world WUI fire episodes. To address this gap, we leveraged data from ongoing randomized crossover trials of long-term use of portable HEPA purifiers in Los Angeles residences. During the Eaton Fire (January 2025), 11 homes were under HEPA intervention and 16 under non-HEPA control. Continuous indoor and outdoor PM2.5 monitoring before, during, and after the Eaton Fire (over 6 weeks) showed outdoor PM2.5 levels rose 148% (19 to 47 µg/m3) and indoor levels 91% (10 to 19 µg/m3) during the fire. HEPA homes had indoor PM2.5 levels 3 µg/m³ (15%, p = 0.01) lower than non-HEPA homes, while outdoor concentrations were comparable. Indoor PM2.5 reductions were unaffected by pre-filter use or clean air delivery rate (CADR)-to-room-volume ratio (0.8–4.9). These findings indicate that portable HEPA purifiers provided statistically significant but modest reductions in PM2.5 levels during WUI fire events. Complementary building-level and behavioral interventions remain critical to reduce indoor exposure in fire-affected communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Due to the changing climate and the growing overlap between human settlements and fire-prone landscapes, the wildland–urban interface (WUI) fires have been increasing in frequency and severity over the years1. Major WUI fires with a disaster declaration in USA such as the Horse River Fire (2016), Chimney Tops 2 Fire (2016), Camp Fire (2018), Marshall Fire (2021), and the most recent Eaton Fire (2025), have occurred commonly in many wildfire-prone areas. Besides the vegetative biomass burning commonly seen in wildfires, WUI fires also consume urban structures and other human-made materials, releasing more toxicants (e.g., dioxins, metals) that can be bound to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) for long-range transportation2,3,4. The recent Los Angeles fires in January 2025 increased the daily average levels of PM2.5 levels to 102 μg/m3 in downtown and to 225 μg/m3 in communities near the burn area5. Importantly, WUI fire smoke can infiltrate buildings and deteriorate indoor air quality6,7,8, leading to greater exposure as people spend most time indoors.

Previous studies have found that the infiltration of wildfire-originated PM2.5 was lower among public buildings with lower air change rate (ACR) and with higher Minimum Efficiency Reporting Value (MERV) ratings for their central ventilation systems9,10. For residential places where modulating ACR and MERV is less feasible, using portable high-efficiency particulate air (HEPA) purifiers has been recommended as a cost-effective mitigation strategy11,12,13. However, this recommendation is largely based on prior studies on traffic air pollutants and indoor PM2.5 sources. To date, there has been a lack of direct evidence to support the effectiveness of HEPA purifiers during a WUI fire. Barn et al.14 have discovered that 1 to 2 days use of HEPA purifiers during forest fire or wood burning episodes had an average effectiveness of 55% in winter and 65% in summer. Xiang et al.15 have found an 18-to-24-h HEPA filtration during a wildfire led to a 48% to 78% decrease in indoor PM2.5 levels. The sources of effect heterogeneities remain unclear but are critical to understand for optimizing HEPA use at the population level.

Prospectively studying real-world WUI fires is challenged by its poor predictability. We seized a unique opportunity of two ongoing randomized cross-over trials of long-term HEPA use (>6 months) in east Los Angeles to compare the impacts of the Eaton fire on indoor air quality among homes with or without HEPA purifiers. In the present study, we analyzed data collected from 27 homes comprised of 11 using HEPA purifiers and 16 using sham filter-controlled air purifiers at the time of Eaton Fire. All these homes were continuously monitored for indoor and outdoor PM2.5 before, during, and after the fire. We aimed to (1) evaluate the extent to which portable HEPA purifier reduced indoor PM2.5 levels during the fire, and (2) explore the influential factors of HEPA effectiveness. Our goal was to gain insights from a real-world WUI fire experience to inform recommendations for widespread use of HEPA purifiers in residences affected by a wildland or WUI fire.

Results

Housing characteristics

Baseline home characteristics and occupants’ behavior information are summarized in Table 1. The majority of homes (>50%) were single-family houses or townhouses, used central ventilation system, and had high window open frequency (6~7 days per week) at baseline (pre-fire period). Room volume represented the room where indoor air monitor was placed. The approximate air changes per hour (ACH) derived from PM2.5 decay rate k were 0.76 h−1 for sham homes and 0.82 h−1 for HEPA homes, which were reasonable and aligned well with literature-reported values from field measurements16. There were no significant differences in any baseline home characteristics or window opening frequency between HEPA and sham homes. The current study was nested in a longer-term HEPA intervention study in which participants were encouraged (but not required) to make changes in their window open/close habits. However, we administered a follow-up questionnaire survey on window-opening frequency during the fire. With an 81% response rate, we found that most participants substantially reduced their window open frequency during the fire compared to baseline (Table S1), suggesting adaptive behaviors in response to poor outdoor air quality.

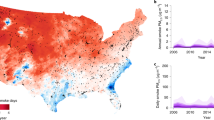

PM2.5 levels

Typical outdoor and indoor PM2.5 time-series plots from a sham home and a HEPA home are shown in Fig. 1. Of all homes, outdoor PM2.5 concentrations increased by an average of 149% during the active fire stage (from a before fire average of 19 µg/m3 to 47 µg/m3), with individual hourly-average concentration peaks reaching up to 629 µg/m3. Outdoor concentrations returned to similar baseline levels during the late-fire stage (12 µg/m3). Likewise, indoor PM2.5 concentrations increased by an average of 90.9% during the active fire stage (from a before-fire average of 10 µg/m3 to 19 µg/m3) and returned to 6 µg/m3 during the late fire stage. The individual time-series plots (12/18/2024 to 2/5/2025) of all 27 homes can be found in Supplementary Information.

The timeline covers three weeks before the fire (grey shading), active fire phase with visbile urban smoke (red shading), three weeks of late fire phase (pink shading), and five days after the fire was officially fully contained (green shading). a A home without a HEPA filter and b A home with HEPA filter. Outdoor PM2.5 is shown in solid black line; indoor PM2.5 in brown (sham home) or blue (HEPA home). All concentrations represent hourly averages. Indoor source peaks are marked in the plots but were removed in statistical analysis. Text boxes to the right of each panel indicate filter status, Air conditioning, house type, and room volume.

We observed no significant differences in outdoor PM2.5 levels between HEPA and sham homes at any stage of the study (i.e., before, active, late, and after the Eaton fire) (Table 1). However, the average indoor PM2.5 concentrations in HEPA homes were significantly lower than those in the sham homes before fire (mean ± SD: 9 ± 5 µg/m3 vs. 11 ± 5 µg/m3) and in the active fire stage (17 ± 16 µg/m3 vs. 20 ± 23 µg/m3) (Table 1, and Fig. 2a). Indoor PM2.5 concentrations were statistically comparable between the two groups in the late and after-fire stages. During these stages, when outdoor PM2.5 levels were lower, there were no significant differences in indoor PM2.5 levels between the HEPA and sham homes. PM2.5 I/O ratio followed a similar pattern to indoor PM2.5 concentrations except during the late fire period. The average PM2.5 I/O ratio in HEPA homes was significantly lower than those in the sham homes before fire (0.53 ± 0.24 vs. 0.61 ± 0.25) and in the active fire days (0.57 ± 0.26 vs. 0.64 ± 0.29). In the late fire stage, the average PM2.5 I/O ratio in HEPA homes was statistical similar to the sham homes (0.63 ± 0.26 vs. 0.62 ± 0.30), and became comparable in the after-fire stage.

a Summary of indoor PM2.5 (left) and I/O ratio (right) by HEPA filter use across fire phases. Data represent mean values; error bars denote standard errors. Indoor source peaks were removed during analysis (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001). b Effect of covariates on indoor PM2.5 concentrations during the active fire period (January 7–11, 2025). Forest plot shows estimated linear effects of parametric covariates from the GAM model. Dots indicate point estimates; horizontal lines indicate their 95% confindence intervals (red = p < 0.05, gray = NS, not significant). c Effect of pre-filter status (i) and room clean air delivery rate (CADR) ratio (ii) on indoor PM2.5 concentrations. Points represent GAM model-derived estimates of indoor PM2.5 change (µg/m³) associated with filter characteristics. Horizontal lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. Error bars represent standard errors. Pre-filter status and Room/CADR ratio were modeled separately. NS = not significant (p ≥ 0.05).

Effects of HEPA and other factors on indoor PM2.5 levels during the fire

We explored the relationship of various household characteristics including HEPA use with indoor PM2.5 levels during the WUI fire (Fig. 2b). The use of HEPA was associated with a 3 µg/m3, or a roughly 15% decrease in indoor PM2.5 levels. In addition, we found that natural ventilation (window), compared to those with a central ventilation system, was associated with a 3.00 (95%CI: −2.79 to 8.80) µg/m3 increase in indoor PM2.5 levels. We did not see clear effects of building age or room volume on indoor PM2.5 concentrations. The results of PM2.5 I/O ratios followed a similar pattern (Fig. S1a).

To ensure the robustness of the 15% indoor PM2.5 reduction generated by our main model, we conducted a series of sensitivity checks. Firstly, we checked potential temporal dependence given our high-frequency time-series data. Signs of temporal autocorrelation were detected (Fig. S2). Therefore, we refitted our original Generalized Additive Models (GAM) with an AR(1) correlation structure within households. The refitted models yielded similar estimates, a negligible autoregressive parameter (ρ = 0.00), and a slightly higher AIC, which confirms that our results were robust to potential temporal autocorrelation (Table S2). Secondly, we conducted sensitivity analyzes using different time-averaging approaches (i.e., 1-h and 3-h indoor PM2.5 averages). The estimated HEPA effects from these two averaging approaches remained consistent in magnitude and direction (Table S3), which reinforces the robustness of our primary findings based on 2-hour averages. Thirdly, we incorporated participant-reported window use during the fire period obtained from a retrospective questionnaire. Although this behavioral data was incomplete (22 out of 27 homes responded), it allowed us to examine if accounting for window use altered the HEPA effect estimate. After adjusting for this covariate, the estimated HEPA effect on indoor PM2.5 levels remained consistent in magnitude and direction (β = −2.22 in the window- adjusted model vs −2.69 in the main model, Fig. S3). Moreover, our findings also remain robust in the proposed three subset sensitivity analyzes (i.e., (1) exclusion of homes on the evacuation list; (2) exclusion of one geographically distant home; and (3) exclusion of home purchasing extra air purifiers during the fire event) (Figs. S4, and S5).

Effect modifications of purifier-related factors

We explored the influence of the purifier characteristics, specifically the presence of pre-filters and the clean air delivery rate (CADR), on the effects of HEPA on indoor PM2.5 levels. The Honeywell model was equipped with a pre-filter, while the Toppin model was not. Of the 11 homes with HEPA, 9 homes had their indoor air monitor in the same room where a purifier with a pre-filter was placed. In terms of the CADR to room volume ratio, 10 out of 11 HEPA homes had this ratio more than 1.0 (h−1, 2.92 ± 1.00). The ratio was categorized as “low” and “high” based on the median level. As shown in Fig. 2c, we did not observe clear evidence in the HEPA-associated PM2.5 reduction between purifiers with and without pre-filters, or between homes of higher versus lower CADR/room ratios. Likewise, HEPA-associated PM2.5 I/O ratio reduction was not significantly differed from the presence of pre-filter or CADR to room volume ratio (Fig. S1b).

Discussion

The present study sought to address an important and timely public health question: whether portable HEPA purifiers reduce indoor PM2.5 exposures during real-world WUI fire events. The study is novel in leveraging ongoing randomized cross-over trials, capturing both pre- and post-fire data, and using calibrated low-cost sensors. The dataset is unique and will contribute to the environmental health and exposure science fields, giving increasing concerns of wildland and WUI fires in the US and globally.

We leveraged ongoing randomized trials of long-term HEPA filtration to prospectively evaluate the effectiveness of HEPA purifiers in reducing indoor PM2.5 levels during a WUI fire. We found that the January 2025 Eaton Fire led to a 91% increase in indoor PM2.5 levels in fire-affected households in the Los Angeles area. Among homes with HEPA purifiers, the indoor levels and I/O ratios of PM2.5 were significantly but modestly lower as compared with sham homes during the fire episode. These results provide real-world supportive evidence on the use of portable HEPA purifiers to mitigate indoor exposure to PM2.5 originating from WUI fires. On the other hand, the 15% decrease in indoor PM2.5 levels was smaller than other HEPA-based air cleaner field studies, regardless of their scenarios 17.

Few previous studies have prospectively assessed the performance of HEPA purifiers in reducing indoor PM2.5 levels during a WUI fire, as it is challenging to plan for such a study due to the unpredictable nature of wildfires. While the efficiency of HEPA filters in removing particles is best evaluated under controlled conditions, there’s a need to assess the effectiveness of using HEPA air purifiers in reducing indoor PM2.5 concentrations in real-world settings. Our study aimed to evaluate the HEPA effectiveness in indoor PM2.5 concentration in households affected by a WUI fire event. In the present study, we assessed HEPA performance throughout all stages of the fire, including 4 days in active fire and 20 days in late fire days, in comparison with non-fire days (before and after the Eaton fire). Because we studied homes that participated in a 6-month or 9-month HEPA trial without supervision from researchers during the fire event, our study provided a real-world reflection on the HEPA filtration with as many heterogeneities across different homes accounted.

We found that HEPA, on average, alleviated but did not prevent the increase of indoor PM2.5 levels during WUI fires as compared to indoor levels during non-fire periods. We saw that some HEPA homes had I/O ratios close to 1 during the fire (Table S4), suggesting HEPA purifiers may be less effective for certain homes. Our behavioral-adjusted sensitivity analysis yielded a slightly attenuated HEPA effect estimate, though it remained directionally consistent with the main model. This suggests that HEPA filtration can provide protection, but its performance is not uniform and depends on other influencing factors. We also considered ambient PM2.5 concentrations across different fire phases. Notably, ambient levels were considerably lower in the Late and After fire periods, when the HEPA effect appeared negligible (Table 1). HEPA filtration was more effective at reducing indoor PM2.5 when outdoor concentrations were higher (Fig. S6). This suggests that the observed lack of effect during later fire phases did not indicate purifier failure but rather reflected limited room for improvement under already low outdoor PM2.5 conditions.

We explored the modification effects of pre-filters and CADR, two key parameters that customers typically consider when purchasing portable HEPA purifiers. Our results suggested that the presence of pre-filters and higher CADR relative to room volume (CADR/volume ratio of 3.1 h−1), was not associated with greater PM2.5 reductions among HEPA homes. The presence of pre-filters did not contribute to additional benefit for PM2.5 reduction (though they may still be useful for coarse particles and extending HEPA filter life). In terms of CADR, indoor PM2.5 concentration should be inversely correlated with CADR of an air purifier normalized by room volume (i.e., the ratio of CADR to room volume). However, this was not observed in the present study. The CADR-to-room-volume ratio among HEPA homes ranged from 0.8 to 4.9, with only one home had the ratio <1.0. Since a CADR/volume ratio of ≥1 is generally considered sufficient for effective room-scale air purification, the limited variability in this metric likely constrained our ability to demonstrate a clear dose–response relationship.

We carefully examined participants’ disaster responses to the fire. Of 27 households, 6 homes were in the evacuation order (2 HEPA homes and 4 sham homes) and 1 sham home received evacuation warning during the fire. In addition, 3 sham homes (defined by the study) purchased their own air purifiers and turned them on during the fire episode. Since these disaster responses could have substantially affected the HEPA use and/or indoor PM2.5 levels, we conducted sensitivity analyzes by excluding evacuated homes or homes that had acquired new HEPA purifiers. In these analyzes, HEPA use was associated with greater reductions in indoor PM2.5 levels. Additionally, for the three sham homes (Home 4,7,10) having acquired portable HEPA purifiers during the fire, two of them (Home 7 and 10) had the after-fire PM2.5 I/O ratio significantly lower as compared to before the fire, which was also noticeable from the timer-series plots (Table S5).

Our study has several notable strengths. Firstly, the concurrent outdoor PM2.5 measurements in each home provided a better estimate of home-specific outdoor PM2.5 levels. Secondly, we leveraged ongoing randomized crossover trials in which approximately half of the participants had HEPA purifiers at home during the fire. Thus, home characteristics and other confounders were balanced between the two groups through randomization in the ongoing HEPA trials. Thirdly, the availability of both pre-fire and post-fire periods allowed us to isolate fire-related changes from background variability.

Meanwhile, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the small sample size limited the statistical power to identify sources of heterogeneity in HEPA performance. Our study used a two-group (HEPA versus sham) comparison. Despite randomization, this type of study design typically requires a larger sample size to minimize differential confounding across groups. Another limitation is the lack of complete data on occupant behaviors and behavioral changes prompted by the fire. Although we retrospectively assessed window-opening frequency during the fire through follow-up questionnaires, the adherence to continuous purifier use was not actively monitored. In addition, the information on AC use during the fire event was not collected. During the fire, participants may have also adjusted behaviors such as purifier run times and AC use, known to influence the effectiveness of HEPA use in reducing indoor PM2.5 levels. Lastly, this study did not directly measure building air leakage, which could be a relevant factor under strong Santa Ana wind conditions18. Increased infiltration driven by wind-induced pressure differences may have reduced HEPA effectiveness even in homes with purifiers offering sufficient CADR.

Nonetheless, our study provides rare real-world evidence on the performance of portable HEPA purifiers in homes during a WUI fire episode. While we observed that HEPA significantly reduced indoor PM2.5 levels relative to sham units, the magnitude of effect was modest (about a 15% reduction). From a broader perspective, even small absolute reductions in PM2.5 can carry public health value during prolonged and widespread wildfire and WUI fire events when millions of people are exposed simultaneously. Our findings emphasized both the role and the limitations of portable HEPA purifiers as an exposure mitigation strategy in a WUI fire episode. While HEPA intervention provided some protection, it was insufficient on its own to fully shield residents from WUI fire smoke. The 15% reduction observed in our study may be less than expected, suggesting that unmeasured factors such as building air leakage, and user behaviors (e.g., AC use, purifier operation patterns) may constrain real-world HEPA effectiveness. Future research to identify and quantify these factors will be essential to better understand the heterogeneity in HEPA performance and guide more targeted behavioral-level interventions. Implementation strategies should therefore emphasize not only on access to HEPA purifiers but also actionable guidance on their optimal use.

Methods

Fire event and study design

The Eaton Fire began in the evening of January 7 in Eaton Canyon, Los Angeles (LA), California. Fueled by strong Santa Ana winds, it rapidly spread into urban LA areas and developed a WUI fraction beyond normal wildfire. The Eaton fire ultimately burnt 14,021 acres and destroyed 9414 residential, commercial and other structures19. After being active for 24 days, the fire was declared fully contained on January 31, 2025.

This study used data from two ongoing residential HEPA filtration crossover trials (Clinical.gov registration IDs were NCT05718245 and NCT05867381) at the time of the Eaton fire. Briefly, households were enrolled in one of the trial cohorts, each consisting of two intervention periods: one with active HEPA filtration and the other with a visually identical non-HEPA filtration (i.e., operating the same air purifier models with HEPA filter removed to simulate noise and airflow without filtration), separated by a washout phase. Every home was equipped with calibrated low-cost air monitors to continuously record real-time indoor and outdoor PM2.5 levels. The two parental trials followed the same overall design with slight differences in duration and cohort size. One has a 6-month intervention period, and the other has a 9-month intervention period. Full trial details are provided in Fig. S7. At the time of the Eaton Fire, 27 households were undergoing one of the trial stages: 16 homes happened to fall in the non-HEPA controlled group (these homes were hereafter referred to as “sham homes”) and 11 homes in the HEPA group. Each household operated two portable HEPA purifiers (Honeywell HPA104, or Toppin C2), both with the same CADR of 170 m3/h. One purifier was placed in the living room and the other in the bedroom, positioned at least 1 m from the walls. Participant homes were asked to keep the air purifiers on all the time since they were consented. The HEPA group used HEPA purifiers intact as purchased, whereas the sham group used the modified purifiers with the HEPA filter removed.

Housing characteristics

The locations of the 27 households relative to the Eaton Fire are shown in Fig. S8. Household features and occupant behaviors were obtained through field visit questionnaires. At baseline, time-fixed building and room features, such as house type, built year, air conditioning type, were collected. Room volume was calculated based on direct measurements. Direct ventilation testing (e.g., tracer gas methods) in this study was not feasible due to logistical constraints. Instead, we estimated home-specific ACH from indoor PM2.5 decay curves observed prior to any purifier deployment. Specifically, we applied an exponential decay model to an indoor PM2.5 peak following an indoor activity event to derive a decay constant (total removal rate k), which can reflect a combination of ventilation and deposition20,21. This variable was used as an approximate household baseline ACH (Fig. S9). Window open frequency was initially assessed at baseline. After all evacuated participants had returned to their homes following the containment of the fire, a follow-up questionnaire was administered retrospectively to assess their window-use behaviors during the fire event. All these housing characteristics were later evaluated as covariates in statistical models.

Indoor and outdoor PM2.5 monitoring

Low-cost air monitors were deployed to measure paired real-time indoor and outdoor PM2.5 concentrations. Homes participating in the 6-month trial used TSI BlueSky™ monitors (Model 8145) for outdoor and TSI Air Assure™ monitors (Model 8144-6) for indoor measurements. Homes participating in the 9-month trial used Purple Air PA-II-FLEX monitors for both outdoor and indoor measurements. These air monitors measured PM2.5 concentrations based on the principle of laser light scattering. The TSI monitors employed Sensirion SPS30 sensors, whereas the Purple Air devices utilized Plantower PMS5003 laser particle sensors. These three brands of air monitors have been validated by previous studies22,23,24. All the monitors used in this study were harmonized internally and calibrated at the central Los Angeles Air Quality Sensor Performance Evaluation Center (AQ-SPEC) located in urban LA, against a station EPA-designated PM2.5 reference monitor (Figs. S10, S11, and Table S5). At participant homes, outdoor air monitors were positioned at a convenient location in the front or back yard; the indoor monitors were placed in either a bedroom or a living room. The monitors streamed real-time data via Wi-Fi and stored the data in the SD card inside the monitors. The connectivity and function were checked daily through online portals.

PM2.5 data processing and indoor source peak removal

We retrieved the data at a 15-min interval. The raw data contained inaccurate data points (e.g., particle sensor declared error). The physically implausible data (<1% of the data points) were removed. Given that this study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of HEPA filtration in reducing indoor concentrations of PM2.5 entering from outdoors, we minimized the influence of indoor sources (e.g., cooking, candle/incense burning) by adopting a previously established method to identify and remove indoor PM2.5 peaks due to indoor sources25 (Fig. S12). This algorithm used indoor and outdoor measurements to distinguish indoor sources and outdoor infiltration. After removing all indoor source peaks (7% of the total data points), the remaining data points (27,649 h in total) were utilized to evaluate indoor and outdoor PM2.5 concentrations during the entire observation.

Statistical analysis

The 27 households were followed from 3 weeks prior to the onset of the Eaton Fire throughout the fire and after the fire. Wildfire smoke distribution in the study area was tracked using NOAA’s Hazard Mapping System (HMS) smoke and fire products, in conjunction with real-time data from the Purple Air Map. Fire progression was categorized into four stages: (1) Before fire (12/18/2024 to 1/6/2025): Pre-fire days used as the pollution reference baseline, (2) Active fire (1/7/2025 to 1/11/2025): Days with both confirmed smoke presence in urban LA reported via HMS and significant elevated outdoor PM2.5 levels, (3) Late fire (1/12/2025 to 1/31/2025): Days when outdoor PM2.5 levels had returned to baseline levels, although the fire remained not fully contained, and (4) After fire (2/1/2025 to 2/5/2025): Days following official full containment of fire. These stages were utilized for descriptive analysis. Group-level comparisons of housing characteristics and PM2.5 exposure averaged at each stage between sham and HEPA homes were assessed using Fisher’s exact test (categorical variables) and Wilcoxon test (continuous variables).

To further evaluate determinants of indoor PM2.5 during the active fire stage, we fitted GAMs with the restricted maximum likelihood estimation, including a household-specific random intercept. Considering the reported outdoor-to-indoor infiltration lag time of up to 115 min during winter26, indoor PM2.5 concentrations were averaged over a 2-h period for use in the models. In the GAM models, the 2-h averaged indoor PM2.5 served as the outcome variable; purifier type (HEPA versus sham filter control) was the main independent variable of interest; and covariates included outdoor PM2.5, ventilation type (central A/C vs window only), house age, and room size. House type was excluded due to limited variation (only one condo/apartment versus 26 single or town houses). Estimated ACH values and window opening frequency were also excluded because these baseline responses could not reliably reflect behaviors during the fire, given previous studies showing that people’s behaviors change during smoke days27. The same model structure was used in assessing the 2-h averaged indoor/outdoor (I/O) PM2.5 ratios as the outcome variable. We also explored whether the following two purifier-related parameters modified the HEPA effectiveness in reducing indoor PM2.5 levels: (1) the presence of a pre-filter in combination of the HEPA filter and (2) CADR relative to room size.

We conducted a series of sensitivity analyzes to assess the robustness of our findings. Firstly, while our primary analysis used 2-h indoor PM2.5 averages, we also tested alternative temporal resolutions using 1-h and 3-h aggregation windows. Second, we performed a behavioral-adjusted sensitivity analysis incorporating self-reported window use during the fire period as a covariate. Due to the incompleteness and potential record bias, this behavioral information was excluded from the main statistical models to preserve statistical power. Thirdly, we ran three subset analyzes: (1) excluding homes on the evacuation list to account for the influence of power outage on air monitors and portable HEPA purifiers, (2) excluding one geographically distant home that appeared less affected by fire smoke, and (3) excluding three homes in the sham group that reportedly used additional purifiers during the fire period. All statistical analyzes were done in R Version 4.3.3. Figures were generated in R and Python.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional review board (IRB) restrictions and the presence of potentially identifiable household information.

References

Tang, W., He, C., Emmons, L. & Zhang, J. Global expansion of wildland-urban interface (WUI) and WUI fires: insights from a multiyear worldwide unified database (WUWUI). Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 044028 (2024).

Tuet, W. Y. et al. Chemical and cellular oxidant production induced by naphthalene secondary organic aerosol (SOA): Effect of redox-active metals and photochemical aging. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–10 (2017).

Spada, N. J. & Hyslop, N. P. Comparison of elemental and organic carbon measurements between IMPROVE and CSN before and after method transitions. Atmos. Environ. 178, 173–180 (2018).

Wong, J. P. S. et al. Effects of atmospheric processing on the oxidative potential of biomass burning organic aerosols. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53, 6747–6756 (2019).

Schollaert, C. et al. Air quality impacts of the January 2025 Los Angeles wildfires: insights from public data sources. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. https://doi.org/10.1021/ACS.ESTLETT.5C00486 (2025).

Silberstein, J. M. et al. Residual impacts of a wildland urban interface fire on urban particulate matter and dust: a study from the Marshall Fire. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 16, 1839–1850 (2023).

Averett, N. After the Smoke Clears: Wildland-Urban Interface Fires and Residues in Nearby Homes. Environ. Health Perspect. 132, 7 (2024).

Reid, C. E. et al. Physical health symptoms and perceptions of air quality among residents of smoke-damaged homes from a wildland urban interface fire. ACS EST Air 2, 13–23 (2024).

Mendoza, D. L. et al. Using indoor and outdoor measurements to understand building protectiveness against wildfire, atmospheric inversion, and firework PM2.5 pollution events. Environments 11, 186 (2024).

Antonopoulos, C., Dillon, H. E. & Gall, E. Experimental and modeled assessment of interventions to reduce PM2.5 in a residence during a wildfire event. Pollutants 4, 26–41 (2024).

Barn, P. K. et al. Portable air cleaners should be at the forefront of the public health response to landscape fire smoke. Environ. Health 15, 1–8 (2016).

Joseph, G., Schramm, P. J., Vaidyanathan, A., Breysse, P. & Goodwin, B. Evidence on the Use of Indoor Air Filtration as an Intervention for Wildfire Smoke Pollutant Exposure A Summary for Health Departments BRACE Technical Report Series Evidence on the Use of Indoor Air Filtration as an Intervention for Wildfire Smoke Pollutant Exposure Ii A Summary for Health Departments Iii (2020).

Burke, M. et al. Exposures and behavioural responses to wildfire smoke. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6, 1351–1361 (2022).

Barn, P. et al. Infiltration of forest fire and residential wood smoke: An evaluation of air cleaner effectiveness. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 18, 503–511 (2008).

Xiang, J. et al. Field measurements of PM2.5 infiltration factor and portable air cleaner effectiveness during wildfire episodes in US residences. Sci. Total Environ. 773, 145642 (2021).

Yamamoto, N., Shendell, D. G., Winer, A. M. & Zhang, J. Residential air exchange rates in three major US metropolitan areas: results from the Relationship Among Indoor, Outdoor, and Personal Air Study 1999–2001. Indoor Air 20, 85–90 (2010).

Ebrahimifakhar, A., Poursadegh, M., Hu, Y., Yuill, D. P. & Luo, Y. A systematic review and meta-analysis of field studies of portable air cleaners: performance, user behavior, and by-product emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 912, 168786 (2024).

Haghighat, F., Brohus, H. & Rao, J. Modelling air infiltration due to wind fluctuations—a review. Build. Environ. 35, 377–385 (2000).

Fire Season Incident Archive | CAL FIRE. https://www.fire.ca.gov/incidents/2025 (2025).

Fu, N. et al. Investigating the reliability of estimating real-time air exchange rates in a building by using airborne particles, including PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10: a case study in Suzhou, China. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 15, 101955 (2024).

Liu, C. et al. A new PM2.5-based CADR method to measure air infiltration rate of buildings. Build. Simul. 14, 693–700 (2021).

Saeed, T. et al. Sustaining Low-Cost PM2.5 Monitoring Networks in South Asia: Technical Challenges and Solutions. https://doi.org/10.5194/EGUSPHERE-2024-1932 (2024).

Jaffe, D. A. & Creekmore, A. Emissions and exposure to NOx, CO, CO2 and PM2.5 from a gas stove using reference and low-cost sensors. Atmos. Environ. 331, 120564 (2024).

Stavroulas, I. et al. Field evaluation of low-cost PM sensors (Purple Air PA-II) under variable urban air quality conditions, in Greece. Atmosphere 11, 926 (2020).

Zhang, H. et al. Partitioning indoor-generated and outdoor-generated PM2.5 from real-time residential measurements in urban and peri-urban Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 845, 157249 (2022).

Han, Y. et al. Influences of ambient air PM2.5 concentration and meteorological condition on the indoor PM2.5 concentrations in a residential apartment in Beijing using a new approach. Environ. Pollut. 205, 307–314 (2015).

Liang, Y. et al. Wildfire smoke impacts on indoor air quality assessed using crowdsourced data in California. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2106478118 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health/National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES033707, R01ES033707-02S1) and Underwriters Laboratories Inc. The authors thank the field team for their home visits to install air monitors, portable HEPA purifiers, and collect survey data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.C. led the data analysis, result visualization, interpretation and manuscript writing. Y.L. provided statistical support in result interpretation and manuscript revision. J.L. contributed to result visualization. C.Q., W.C., Z.Y., Y.G., D.K., M.W., and M.B. coordinated the field data collection. F.G., M.B., Z.C., and J.Z. contributed to result interpretation and manuscript revision. All authors reviewed the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, R., Lin, Y., Liao, J. et al. Fine particulate matter levels and HEPA filtration in Los Angeles homes during a wildland-urban-interface fire. npj Clean Air 2, 3 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00042-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00042-5