Abstract

Environmental epidemiological studies often use both station-monitored and personal air pollutant exposures, which frequently yield different results. We aimed to identify key considerations when choosing between these measures. In a panel study of 37 college students assessed six times across three seasons for cardiorespiratory outcomes, personal PM2.5 and O3 exposures were monitored for 5 days with wearable sensors before each health assessment, alongside concurrent measurements from nearby monitoring stations. The association between station-monitored and personal concentrations was stronger for PM2.5 (regression coefficient: 0.51 ± 0.16) than for O3 (regression coefficient: 0.19 ± 0.15). Both station-monitored and personal PM2.5 were associated with decreased forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and increased fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO). In contrast, only station-monitored O3 was associated with decreased FEV1, FVC, increased FeNO, and worsening augmentation index (AI) and blood pressure. Personal O3 showed mostly null associations or even “seemingly beneficial” associations with AI, FEV1, and FVC. These findings suggest station-monitored PM2.5 can serve as a reasonable proxy for personal exposure in studies with minimal indoor PM2.5 sources. However, this may be unsuitable for O3, given its high spatial variability and potential differences in exposure to ozone-derived reaction products.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exposures to air pollutants such as ozone (O3)and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) have been widely associated with cardiorespiratory mortality and morbidity1,2,3. In previous studies, two approaches have been often used to assess air pollutant exposures. One is to measure personal air pollutant exposures; and the most common approach is to use outdoor air pollutant concentrations. Compared to outdoor air pollutant concentrations4,5, personal air pollutant exposures are generally considered to capture exposures more accurately6, because it accounts for exposure from indoors where people spend the majority of time7,8. However, it is important to note that assessing personal air pollutant exposures could be logistically impractical in large population-based epidemiological studies.

Therefore, it is necessary to assess whether outdoor air pollutant concentrations could serve as reliable proxies for personal air pollutant exposures. Although people spend most of their time indoors, and indoor PM2.5 exposure is the dominant contributor to personal exposure9, the variability in outdoor PM2.5 concentrations often drives the variability in personal exposure estimates10. This is primarily because indoor PM2.5 emissions tend to have relatively smaller day-to-day variability compared to outdoor levels. As a result, outdoor PM2.5 concentrations have been often used as a proxy for personal PM2.5 exposure. For example, multiple studies have demonstrated moderate to high correlations between outdoor PM2.5 levels and personal PM2.5 concentrations11,12,13, especially in environments with minimal indoor sources, such as student dormitories14. In contrast, such correlations are typically weaker for O313,15. This discrepancy is partially due to the large spatial variability in ambient O3 concentrations, as O3 is a secondary pollutant formed through photochemical reactions involving precursor pollutants (e.g., NOₓ and VOCs) and sunlight16,17, both of which can vary substantially across the space. Furthermore, O3 is a highly reactive compound that can be consumed by various reactants present outdoors (e.g., nitric oxide freshly emitted from gasoline or diesel-powered vehicles) and indoors (e.g., nitric oxide from gas stoves and organic compounds on indoor surfaces and in the air). However, it remains unclear how the performance of station-monitored O3 exposure compares with that of personal exposure in epidemiological studies. This is an important question given logistical challenges that may preclude the use of personal monitoring.

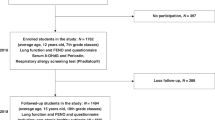

To explore these factors, we conducted a panel study of 37 participants in Guangzhou, China, measuring cardiorespiratory outcomes at 6 clinical visits per participant along with assessing station-monitored outdoor PM2.5 and O3 levels and real-time personal exposures prior to each clinical visit. We aim to (1) analyze the association between personal air pollutant exposures and stationary concentrations, both overall and separately when participants were indoors and outdoors; (2) compare the associations between cardiorespiratory responses using personal versus stationary concentration measurements; and (3) identify the key factors for choosing between station-monitored and personal exposure measurements in epidemiological studies.

Results

Participant characteristics and air pollution levels

Among the total of 42 eligible participants recruited, 4 participants withdrew before the first visit, and 1 participant withdrew after the third visit. Ultimately, 37 participants were included in the statistical analysis. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics and cardiorespiratory outcomes of the participants across all 6 visits. Among the 37 participants, the average age was 21.0 ± 1.0 years old, with 25 participants (67.6%) being female. The demographic characteristics, health outcomes, and average exposure concentrations of air pollutants at each clinical visit are summarized in Supplementary Table S1.

Spearman correlations among environmental exposure are shown in Fig. 1. The correlation between station-monitored PM2.5 and personal exposure to PM2.5 was 0.448 (p < 0.001), while lower correlation was observed between station-monitored O3 and personal exposure to O3 with 0.269 (p < 0.001).

Comparison of the station-monitored concentrations and personal exposures

The comparison of the station-monitored concentration and personal exposure is shown in Fig. 2, with specific values provided in Supplementary Table S2 and Supplementary Table S3. During the five days prior to each of the clinical visits, the regression coefficients for the daily station-monitored O3 exposure on personal O3 exposure ranged from −0.05 to 0.47, with a median coefficient of 0.17. In contrast, the regression coefficients for daily station-monitored PM2.5 exposure on personal PM2.5 exposure ranged from 0.25 to 0.84, with a median coefficient of 0.49, which was notably higher than that of O3 (Fig. 2A). These coefficients remain stable when stratified by indoor and outdoor environments. The regression coefficients of indoor and outdoor personal exposure of PM2.5 exhibited strong associations with the exposure obtained from monitoring stations, with a median of 0.50. In contrast, the corresponding coefficients of indoor and outdoor personal exposure of O3 were both notably lower, with a median of 0.11 (Fig. 2B). As participants spent most of their time indoors (see Table S4), indoor cumulative exposure to both PM2.5 and O3 constituted a significantly larger proportion of cumulative exposure compared to outdoor cumulative exposure. On average, indoor personal exposure to PM2.5 and O3 accounted for 83.33% and 83.62% of the cumulative individual exposure, respectively (Fig. 2C). However, the average exposure levels to air pollutants indoors and outdoors showed considerable similarity among individual participants. The average personal exposure to PM2.5 indoors and outdoors was 21.93 μg/m3 and 22.33 μg/m3, respectively. Meanwhile, the corresponding exposure to O3 was 65.60 μg/m3 and 66.07 μg/m3, respectively (Fig. 2D).

The regression coefficients between station-monitored air pollutants and personal exposure, adjusted for season (A), the regression coefficients between station-monitored air pollutants and personal exposure when participants are indoors vs. outdoors, adjusted for season (B), contributions of outdoor exposure and indoor exposure to total personal exposure (C), and comparison of average personal O3 or PM2.5 levels when participants are outdoors vs. indoors (D).

Respiratory responses to air pollution

The associations between station-monitored concentration and personal exposure to O3 and PM2.5 with lung function and airway inflammation are illustrated in Fig. 3, specific estimates are shown in Supplementary Table S4. Notably, the associations of station-monitored O3 with FEV1 differed largely in both direction and estimates from those of personal exposure to O3. Each IQR increase in 0–3 days cumulative station-monitored O3 was associated with a −1.24% (95% CI: −2.27%, −0.21%) change in FEV1, while each IQR increase in cumulative personal exposure over the same period was associated with a 0.59% (95% CI: −0.20%, 1.39%) increase in FEV1. This discrepancy persisted throughout the preceding 5 days. Similar results were observed in FVC, each IQR increase in the 0–2 days cumulative station-monitored O3 concentration was associated with a change of −0.42% (95% CI: −1.44%, 0.60%), compared to 0.56% (95% CI: −0.23%, 1.34%) for personal exposure. In addition, although both station-monitored O3 and personal exposure to O3 showed an insignificant association with FeNO, the association was stronger for station-monitored concentration than for personal exposure, with changes of 11.81% (95% CI: −1.48%, 25.10%) and −1.74% (95% CI: −11.80%, 8.32%) per IQR increase over 0–1 days, respectively.

In contrast to O3, the associations between station-monitored PM2.5 and the respiratory measures were similar in both direction and estimates to those of personal exposure to PM2.5. For lung function, each IQR increase in 0–4 days cumulative station-monitored PM2.5 was associated with a -0.21% (95% CI: −1.23%, 0.82%) change in FEV1, while each IQR increase in 0–4 days cumulative personal exposure was associated with a -0.87% (95% CI: −1.64%, −0.11%) change in FEV1. Each IQR increase in cumulative station-monitored concentration and personal exposure to PM2.5 over 0–3 days was associated with changes in FVC of -0.59% (95% CI: −1.57%, 0.38%) and -1.26% (95% CI: −1.98%, −0.53%), respectively. For FeNO, the strongest associations were observed with station-monitored cumulative concentration on 0 days, showing a change of 1.28% (95% CI: −7.18%, 9.74%) per IQR increase, and with personal cumulative exposure on 0 days, showing a change of 4.26% (95% CI: −3.51%, 12.03%) per IQR increase.

Cardiovascular responses to air pollution

The associations of cardiovascular outcomes with station-monitored concentration and personal exposure to O3 and PM2.5 are shown in Fig. 4, specific estimates are shown in Supplementary Table S5. Station-monitored PM2.5 and personal exposure to PM2.5 showed similar estimates, except for blood pressure. Positive associations were observed between station-monitored PM2.5 and AI, with changes of 5.19% (95% CI: −4.19%, 14.57%) and 5.14% (95% CI: −5.00%, 15.28%) per IQR increase in 0–4 days and 0–5 days of cumulative station-monitored PM2.5, respectively. Similarly, personal PM2.5 exposure was associated with changes of 7.33% (95% CI: 0.20%, 14.45%) and 6.21% (95% CI: –1.09%, 13.52%) over the same periods. In addition, we observed that the associations between station-monitored O3 and AI, SBP, and DBP differed considerably in both direction and estimates from those with personal exposure to O3. Positive associations between station-monitored O3 and AI were observed for all the cumulative exposure days, except for 0–4 and 0–5 days, while the association with personal exposure to O3 was significantly negative. Similarly, positive associations were observed for blood pressure with station-monitored concentration, while negative associations were found with personal exposure.

Sensitivity analysis

The associations between station-monitored concentration and personal exposure to PM2.5 and O3 remained relatively unchanged after excluding the participants who had respiratory infection during each of the clinical visits (Supplementary Fig. S1 and Supplementary Fig. S2) and after excluding the participant who did not complete all six visits (Supplementary Fig. S3). After limiting the calculation of personal daily exposure to a minimum of 16 h of available data, the associations between personal exposure to air pollutants and cardiorespiratory function, as well as respiratory inflammation, remained stable compared to the main analysis (Supplementary Fig. S4 and Supplementary Fig. S5).

Discussion

In this panel study of 37 healthy young adults, we compared station-monitored concentrations with personal sensor measurements in their associations with a set of biomarkers of cardiorespiratory pathophysiology. We found that both station-monitored concentration and personal exposures to PM2.5 were associated with decreased FEV1, FVC, and increased FeNO level. However, adverse associations on respiratory outcomes were observed only for station-monitored O3, but not for personal O₃, with the exception of FEV₁/FVC; and the association between station-monitored O3 and FeNO was stronger than that of personal exposure. For cardiovascular biomarkers, a positive association for PPI was observed consistently for both station-monitored PM2.5 and personal PM2.5 exposure. In contrast, station-monitored concentration and personal O3 exposure showed completely opposite associations with blood pressure and AI.

Given that personal exposure measurements are often impractical, especially in large population studies, station-monitored concentrations have been commonly used as a proxy for air pollution exposure levels18,19. In the context of an epidemiologic investigation of associations between exposure and health outcomes, as long as station-monitored and personal exposure concentrations are correlated, fixed-site monitoring data could be a reasonable proxy of personal exposure. This notion is supported in the present study for PM2.5 by showing (1) personal exposure to PM2.5 was highly correlated with stationary PM2.5 levels and (2) associations of cardiorespiratory outcomes with PM2.5 were similar for personal and station-monitored data.

In locations where outdoor PM2.5 levels are high, indoor PM2.5 concentrations are largely driven by outdoor infiltration with insignificant or negligible contribution from indoor sources. This could make station-monitored and personal PM2.5 concentrations strongly correlated. For example, a study of college students in Beijing, China, found a correlation of 0.678 between personal and station-monitored PM2.5 exposure20. A study conducted in the same city of this study (Guangzhou) reported correlations ranging from 0.25 to 0.79 across 7 districts21. A review of 44 studies from around the world reported an overall correlation of 0.63 (95% CI: 0.55, 0.71) between personal and station-monitored PM2.522. Nonetheless, none of these studies examined whether outdoor PM2.5 concentrations measured at fixed sites and personal PM2.5 exposures differ in their associations with health outcomes.

Our present study supports the use of fixed-site outdoor PM2.5 concentrations as a proxy for PM2.5 exposure in epidemiologic studies examining the associations between PM2.5 and health outcomes. From the point of toxicology that dose makes poison, personal exposure represents inhaled dose from all sources for a given time period while ambient concentration cannot capture exposures resulting from non-ambient sources (e.g., indoor sources). Therefore, even when fixed-site concentrations and personal exposures are reasonably correlated, it is not surprising to observe heterogeneity in their associations with health outcomes. For example, previous studies in children, who typically have relatively simple daily routines and exposure patterns, showed a high correlation between personal and ambient PM2.5 exposure (r = 0.60). Both types of PM2.5 exposure metrics were positively associated with FeNO and negatively associated with FEV1, with the association being stronger for personal exposure than for station-monitored concentration23,24,25. Another study of 46 subjects with diverse occupations reported a correlation of 0.52 between ambient and personal PM2.5, however, significant increases in FeNO were observed only in association with personal exposure26. While In a cohort of 65 non-smoking subjects with relatively low correlations (r = 0.19) between station-based and personal PM2.5 measurements, adverse associations on cardiovascular outcomes were observed only for personal exposure27. Thus, the correlation between personal and ambient PM2.5 levels may depend on individual daily activities and living environment. In our study, which included university students, we observed a high correlation between the two exposure metrics and little difference in their associations with cardiorespiratory outcomes.

In contrast to PM2.5, our results suggested that adopting the same strategy for O3 needs more caution for several reasons. First, we found low correlations between station-monitored ozone levels and personal ozone levels when participants were outdoors, suggesting high spatial variability in outdoor ozone levels within the urban area28,29, likely driven by the strong influence of local O3 sinks such as nitric oxide (NO) freshly emitted by motor vehicles and ozone-reactive surfaces (trees, painted walls, etc.)29,30. Second, participants spent majority of time in indoors, where O3 can interact with indoor substances to form secondary pollutants termed ozone reaction products, including aldehydes, ketones, dicarbonyls, organic acids, and peroxy acids, as well as organic nitrates31. Some of ozone reaction products are expected to be more toxic than O3 itself32.

Recent studies suggest that exposure to ozone reactive products, as compared with O3 itself, exhibited greater associations with cardiorespiratory outcomes32. Because ambient O3 contributes to both ozone and ozone reactive products, it cannot be ascertained whether the associations of ambient O3 levels with adverse cardiorespiratory outcomes observed in our studies or previous studies were driven primarily by ozone or by ozone reaction products. Herein, this study provides new evidence to clarify this issue. Specifically, we observed that personal ozone exposure, which more accurately reflects individual-level inhalation of ozone, was not significantly associated with cardiorespiratory outcomes. In contrast, ozone levels from outdoor monitoring stations showed significant associations with adverse cardiorespiratory outcomes. This discrepancy suggests that the observed associations with station-monitored O3 may not be due solely to direct O3 exposure but may, instead, reflect the influence of co-exposure to ozone reaction products, especially those generated indoors or in the breathing zone (O3 does react with skin lipids readily33). In addition, indoor ozone can react with surfaces and building materials, resulting in significant ozone decay indoors34. Temperature and humidity also influence the chemical reactivity of ozone on indoor surfaces35. Moreover, because individuals spend most of their time indoors, they are likely to be exposed predominantly to ozone reaction products rather than ozone itself32. These findings suggest the potential importance of ozone reaction products as key contributors to O3-associated cardiorespiratory outcomes36. They also emphasize the need for more refined exposure assessments that account for complex ozone chemical transformations occurring in real-world environments.

There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, all participants in this study were recruited from university students, who spent the majority of their time indoors (dormitories and classrooms) in the absence of cooking and other household activities encountered in a more typical housing environment. Therefore, extrapolating the results of this study to other populations should be cautious. Secondly, we did not measure indoor-outdoor air change rate (ventilation conditions), which may have potentially influenced the relationships between personal and station-monitored concentrations. In addition, the observed associations of cardiorespiratory function and FeNO with PM2.5 and O3 exposures may be confounded by some unmeasured co-pollutant exposure, such as VOCs and semi-volatile organic compounds (SVOCs). As this was an observational study, all participants followed their usual daily routines; therefore, unmeasured residual confounders such as caffeine intake and physical activity cannot be entirely excluded.

In a cohort of college students living on a university campus located in the Chinese city of Guangzhou, station-monitored and personal sensor concentrations were more strongly correlated for PM2.5 (r = 0.448) than for ozone (r = 0.269). Both station and personal concentrations for PM2.5 showed similar associations with biomarkers of cardiorespiratory pathophysiology. This finding supports the use of ambient PM2.5 concentrations as a proxy of personal exposure in epidemiology studies when fixed-site and personal measurements are well correlated. In contrast, only station-monitored O3 showed positive associations with multiple biomarkers, whereas personal O3 exposure showed null, or even negative, associations. This ozone finding, along with emerging evidence in the literature, suggests personal ozone monitoring may be associated with greater confounding by ozone reaction products than ambient O3 concentrations in epidemiologic studies.

Methods

Study participants

This study was conducted on the campus of Guangzhou Medical University, located in Guangdong Province, China, from September 2020 to October 2022. Eligible participants were recruited from the university students based on the following criteria: (1) residing in university dormitories during the study period to reduce the heterogeneity in variations of lifestyle, dietary patterns, and exposures to indoor pollutants, as cooking and smoking were not permitted in participants’ dormitories; (2) absence of chronic respiratory or cardiovascular disease; (3) not taking any prescribed medications that may interfere with the respiratory function for at least the preceding month; and (4) not being exposed to active or passive smoking regularly. Physical examination, blood tests and lung function tests were conducted to ensure all participants meet the inclusion criteria. All participants provided written informed consent upon enrollment. The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethical Committee of The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University [2020, No. 90].

Study design

Guangzhou city (23°07′N, 113°16′E) is located in southern China and characterized by a humid subtropical climate. During winter, the city typically experiences lower levels of O3 but higher concentrations of PM2.5. In spring, O3 levels typically remain low, while PM2.5 concentrations decrease from winter time. Conversely, summer witnesses higher O3 levels and lower PM2.5 concentrations. Therefore, Guangzhou offers a natural seasonal variation in concentration environment to investigate the association of respiratory health with PM2.5 and O3. In this study, we followed participants across three distinct seasons. Each participant completed two health assessments per season, with a minimum interval of five days between clinical visits within the same season (see Fig. 5). Each clinical visit lasted about 4 h and was conducted under resting-state, during which participants completed the assigned clinical measurements.

Health outcome measurement

We collected individual data on demographic characteristics (age, gender, height, and weight) and lung function at enrollment. At each clinical visit, lung function indicators, including forced expiratory volume in the first second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC), and FEV1/FVC ratio, were measured using spirometry (PONY FX, Cosmed, Italy). Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was measured as a biomarker of airway inflammation using a NIOX VERO device (Circassia Pharmaceuticals Inc., USA). Cardiovascular function indicators, including pulse wave velocity (PWV), augmentation index (AI), pulse pressure index (PPI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured by a cardiovascular and peripheral vascular testing instrument (VICORDER, SMT Medical, Würzburg, Germany). Additionally, height and weight were measured to calculate body mass index (BMI). All these health outcomes were measured by physicians or technicians from The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. Participants were also required to report any respiratory infections and their activity patterns, specify whether they were indoors or outdoors each hour during the five days prior to each of the clinical visits. The study was carried out during most of the COVID-19 period. As such, in-vehicle exposures were very limited among the student participants who did not have a car.

Air pollution exposure assessment

Daily air pollutant concentrations were obtained from the nearest monitored stations within a 4-kilometer straight-line distance of each campus. Supplementary Fig. 6 illustrates the locations of both campuses along with their respective nearest air monitored sites.

For the personal exposure assessment, participants were required to carry a personal monitor for at least 5 days preceding each clinical visit when outcome measurements were made. Researchers at Duke University developed these monitors over multiple years, which integrate Plantower PMS3003 sensors for PM2.5 and Alphasense OX-A4 sensors for O337. They have been utilized and validated in several previous studies38,39. We calculated daily personal exposure based on the minute-level data from the wearable monitors that had been calibrated by co-locating them with an established high-performance air pollution measurement station, further details on the co-location calibration are provided in Supplementary Table S6.

Statistical analysis

We report mean with standard deviation (SD) and percentage for participants’ baseline characteristics. Correlations among station-monitored PM2.5, station-monitored O3, personal exposure to PM2.5, personal exposure to O3, ambient temperature, and relative humidity were determined using Spearman’s correlations.

We investigated the relationship between station-based concentration and personal exposure for each subject, including the season of the visit as a covariate in the regression model. Given that personal activity patterns might influence these associations, we further analyzed these season-adjusted relationships stratified by whether the subject was in an indoor or outdoor environment. Additionally, to compare the relative contributions of personal indoor and outdoor exposures to total personal exposure, we calculated the proportions by dividing cumulative indoor and outdoor exposures by total personal exposure, respectively. Furthermore, we compared average personal exposure concentrations to air pollutants between indoor and outdoor environments at the individual level. Due to scheduling constraints of the measurement equipment, FeNO, lung function, and cardiovascular function indicators for the same individual may not be measured on the same day, with a maximum gap of three days. Therefore, we primarily presented the results of the correlation analysis and descriptive statistics based on the FeNO measurement date. For the subsequent association analyses with the outcomes, the definition of lag days was strictly based on the exact outcome measurement date.

We used linear mixed-effect models (LMMs) which included the subject ID as random effects to examine the associations between the cardiorespiratory outcomes and exposures to PM2.5 and O3 with different lag structures. These included current day exposure at the time of outcome measurement (0 day), and cumulative exposure over multiple days: 0–1 day (representing the moving average exposure from the current day to 1 day preceding the outcome measurement), 0–2 days, 0–3 days, 0–4 days, and 0–5 days. The two pollutant models were further adjusted for the 2-day average (lag 0–1) temperature and relative humidity, as previous studies have shown that the lag 0–1 ambient temperature exhibited the strongest associations with cardiorespiratory outcomes40. In addition, we adjusted for gender, age, BMI, and whether the participant had a respiratory infection. From the model output, we calculated the percentage change and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) of the health outcomes associated with an interquartile range (IQR) increase in exposure to air pollutants.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of our main results. Firstly, we excluded participants who had respiratory infection during each of the clinical visits. Secondly, one participant completed only five cardiovascular indicator measurements, so we excluded this participant from the analysis as part of the sensitivity analysis. Thirdly, due to partial missing hourly values in personal monitor records, we limited the calculation of personal daily exposure to a minimum of 16 h of available data and further investigate the associations of respiratory health with daily air pollution exposure. All statistical analyses were conducted using “lme4” in R software (version 4.3.2). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to institutional restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable requests.

References

Momtazmanesh, S. et al. Global burden of chronic respiratory diseases and risk factors, 1990-2019: an update from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. eClinicalMedicine 59, 101936 (2023).

Cohen, A. J. et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. Lancet 389, 1907–1918 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Ambient particulate air pollution and daily mortality in 652 cities. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 705–715 (2019).

Yao, Y. et al. Susceptibility of individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to respiratory inflammation associated with short-term exposure to ambient air pollution: a panel study in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 766, 142639 (2021).

Zhang, Z. et al. Associations between outdoor air pollution, ambient temperature and fraction of exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) in university students in northern China—a panel study. Environ. Res. 212, 113379 (2022).

Larkin, A. & Hystad, P. Towards personal exposures: how technology is changing air pollution and health research. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 4, 463–471 (2017).

Chen, T. et al. Acute respiratory response to individual particle exposure (PM1.0, PM2.5 and PM10) in the elderly with and without chronic respiratory diseases. Environ. Pollut. 271, 116329 (2021).

Evangelopoulos, D. et al. Personal exposure to air pollution and respiratory health of COPD patients in London. Eur. Respir. J 58, 2003432 (2021).

Borgini, A. et al. Personal exposure to PM2.5 among high-school students in Milan and background measurements: the EuroLifeNet study. Atmos. Environ. 45, 4147–4151 (2011).

Meng, Q. Y., Spector, D., Colome, S. & Turpin, B. Determinants of indoor and personal exposure to PM2.5 of indoor and outdoor origin during the RIOPA study. Atmos. Environ. 43, 5750–5758 (2009).

Chen, X.-C. et al. Indoor, outdoor, and personal exposure to PM2.5 and their bioreactivity among healthy residents of Hong Kong. Environ. Res. 188, 109780 (2020).

Johannesson, S., Gustafson, P., Molnár, P., Barregard, L. & Sällsten, G. Exposure to fine particles (PM2.5 and PM1) and black smoke in the general population: personal, indoor, and outdoor levels. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 17, 613–624 (2007).

Meng, Q., Williams, R. & Pinto, J. P. Determinants of the associations between ambient concentrations and personal exposures to ambient PM2.5, NO2, and O3 during DEARS. Atmos. Environ. 63, 109–116 (2012).

Xie, Q. et al. High contribution from outdoor air to personal exposure and potential inhaled dose of PM2.5 for indoor-active university students. Environ. Res. 215, 114225 (2022).

Niu, Y. et al. Estimation of personal ozone exposure using ambient concentrations and influencing factors. Environ. Int. 117, 237–242 (2018).

Lee, H. J., Kuwayama, T. & FitzGibbon, M. Trends of ambient O3 levels associated with O3 precursor gases and meteorology in California: synergies from ground and satellite observations. Remote Sens. Environ. 284, 113358 (2023).

Lu, Y. et al. Characteristics and sources analysis of ambient volatile organic compounds in a typical industrial park: Implications for ozone formation in 2022 Asian Games. Sci. Total Environ. 848, 157746 (2022).

Lei, J. et al. Fine and coarse particulate air pollution and hospital admissions for a wide range of respiratory diseases: a nationwide case-crossover study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 52, 715–726 (2023).

Lu, W. et al. Short-term exposure to ambient air pollution and pneumonia hospital admission among patients with COPD: a time-stratified case-crossover study. Respir. Res. 23, 71 (2022).

Lin, C. et al. The relationship between personal exposure and ambient PM2.5 and black carbon in Beijing. Sci. Total Environ. 737, 139801 (2020).

Jahn, H. J. et al. Ambient and personal PM2.5 exposure assessment in the Chinese megacity of Guangzhou. Atmos. Environ. 74, 402–411 (2013).

Boomhower, S. R. et al. A review and analysis of personal and ambient PM2.5 measurements: implications for epidemiology studies. Environ. Res. 204, 112019 (2022).

Delfino, R. J. et al. Personal and ambient air pollution is associated with increased exhaled nitric oxide in children with asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 114, 1736–1743 (2006).

Delfino, R. J. et al. Association of FEV1 in asthmatic children with personal and microenvironmental exposure to airborne particulate matter. Environ. Health Perspect. 112, 932–941 (2004).

Delfino, R. J. et al. Personal and ambient air pollution exposures and lung function decrements in children with asthma. Environ. Health Perspect. 116, 550–558 (2008).

Fan, Z. et al. Personal exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) and respiratory inflammation of common residents in Hong Kong. Environ. Res. 164, 24–31 (2018).

Brook, R. D. et al. Differences in blood pressure and vascular responses associated with ambient fine particulate matter exposures measured at the personal versus community level. Occup. Environ. Med. 68, 224–230 (2011).

Yao, Y. et al. Transmission paths and source areas of near-surface ozone pollution in the Yangtze River delta region, China from 2015 to 2021. J. Environ. Manage. 330, 117105 (2023).

Ren, J., Hao, Y., Simayi, M., Shi, Y. & Xie, S. Spatiotemporal variation of surface ozone and its causes in Beijing, China since 2014. Atmos. Environ. 260, 118556 (2021).

Wang, H. et al. Seasonality and reduced nitric oxide titration dominated ozone increase during COVID-19 lockdown in eastern China. Npj Clim. Atmospheric Sci. 5, 24 (2022).

Weschler, C. J. & Nazaroff, W. W. Ozone loss: a surrogate for the indoor concentration of ozone-derived products. Environ. Sci. Technol. 57, 13569–13578 (2023).

He, L. et al. Ozone reaction products associated with biomarkers of cardiorespiratory pathophysiology. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 207, 1243–1246 (2023).

Wisthaler, A. & Weschler, C. J. Reactions of ozone with human skin lipids: sources of carbonyls, dicarbonyls, and hydroxycarbonyls in indoor air. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 6568–6575 (2010).

Moriske, H.-J., Ebert, G., Konieczny, L., Menk, G. & Schöndube, M. Concentrations and decay rates of ozone in indoor air in dependence on building and surface materials. Toxicol. Lett. 96–97, 319–323 (1998).

Nazaroff, W. W. & Weschler, C. J. Indoor ozone: concentrations and influencing factors. Indoor Air 32, e12942 (2022).

He, L. et al. Indoor ozone reaction products: contributors to the respiratory health effects associated with low-level outdoor ozone. Atmos. Environ. 340, 120920 (2025).

Zheng, T. et al. Field evaluation of low-cost particulate matter sensors in high- and low-concentration environments. Atmospheric Meas. Tech. 11, 4823–4846 (2018).

Barkjohn, K. K. et al. Using low-cost sensors to quantify the effects of air filtration on indoor and personal exposure relevant PM2. 5 concentrations in Beijing, China. Aerosol Air Qual. Res. 20, 297–313 (2020).

Liu, M. et al. Using low-cost sensors to monitor indoor, outdoor, and personal ozone concentrations in Beijing, China. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 22, 131–143 (2020).

Kouis, P., Kakkoura, M., Ziogas, K., Paschalidou, A. Κ & Papatheodorou, S. I. The effect of ambient air temperature on cardiovascular and respiratory mortality in Thessaloniki, Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 647, 1351–1358 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank the study participants and Dr. M. Bergin from Duke University for providing the personal sensor devices and Dr. K Barkjohn for her suggestions on sensor calibration. This study was not supported by any grants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. and Y.C. wrote the manuscript. Y.C. and K.X. conducted the subject’s recruitment and clinical measurement. S.Z. and J.K. performed the statistical analysis. Y.L. and L.H. helped plan the statistical analysis, reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.Z. and K.L. conceived of the study, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Chen, Y., Xiang, K. et al. Key factors for selecting PM2.5 and ozone exposure assessment methods in epidemiological studies. npj Clean Air 2, 2 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00045-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-025-00045-2