Abstract

Understanding the seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is crucial for cost-effective seasonal RSV prophylaxis administration. The impact of short-term changes in air pollution and meteorological factors on RSV epidemics, particularly their spatial variations, remains unclear. We conducted a time-series analysis to investigate the association between short-term environmental changes and weekly RSV infection in Chile. Weekly data on the number of new laboratory RSV tests and confirmed RSV-positive cases, meteorological factors, and air pollutants were collected from 16 Chilean regions (2015–2018). We fitted a quasi-Poisson regression to evaluate the link between short-term environmental changes and RSV infection in each region. We utilized random effects meta-analyses to pool the region-specific estimates. Subgroup analyses were further conducted to assess variations by socio-economic and geographical context. Nationwide associations were observed between weekly average temperature and RSV activity, with a 1 °C increase being positively associated with an 8.2% (95% confidence interval: 0.87–0.97) decrease in RSV positivity at a lag of 3 weeks. In addition, we found significant positive nationwide associations between air pollutants, i.e., nitrogen dioxide (\({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\)) and particulate matter smaller than 2.5 μm (\({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\)), and RSV activity. A 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) concentrations was positively associated with an increase in RSV positivity of 3.4% (1.00–1.06) and 10.2% (1.05–1.15) at lags of 3 weeks, respectively. We also observed regional variations of environmental impacts on RSV activity across Chile, including \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and particulate matter smaller than 10 micrometers (\({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\)). The study suggests that improving air quality could potentially lower the RSV activity, especially in highly polluted areas. Furthermore, temperature and air quality changes may be used for predicting short-term shifts in RSV activity, informing RSV prevention efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality in children (\(\le\)5 years) and elders (\(\ge\)60 years) worldwide. RSV is one of the leading causes of acute lower respiratory infections (ALRI) in children under 5 years, resulting in an estimated 33 million RSV-associated ALRI episodes worldwide1. Approximately 470,000 RSV-related hospitalizations in elders in high-income countries were also estimated2.

RSV poses a substantial disease burden and high medical expenditures in Chile3. Around 60% of children are infected by RSV in their first year, and nearly all have encountered the virus by the age of two4. Moreover, severe primary RSV infection is associated with a 1.73-fold increased risk of experiencing three or more wheezing episodes within the following year5. Recognizing this substantial burden, passive immunization, Palivizumab, has long been indicated for high-risk infants in Chile3,6. Since 2024, Chile has implemented the nationwide Nirsevimab-based immunization program to alleviate the substantial RSV disease burden6. Given the high cost and relatively limited duration of protection (approximately 6 months), the optimal timing of initiation for such RSV prophylaxis is just prior to the onset of RSV epidemic seasons.

Current evidence indicates that geographical and meteorological factors are associated with the onset timing of RSV season7. Global-level systematic analyses have identified the latitudinal gradients in the onset of RSV season and relevant meteorological factors, including temperature and humidity8. RSV activity has also been associated with elevated levels of air pollutants, including fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 2.5 \({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{m}}\) \(\left({\rm{P}}{{\rm{M}}}_{2.5}\right)\) and nitrogen dioxide (\({\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}\)), etc9,10. In Santiago, Chile, cold temperatures have been shown to correlate with increased RSV activity11. High-level concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) have also been linked to the elevated risk of RSV hospitalization in the city12.

Existing studies on the impact of short-term air pollution have primarily focused on individual area scales, e.g., cities, while evidence across multiple locations remains scarce. Further investigation is needed to understand how these associations may vary across spatial characteristics (e.g., latitude gradients), to provide more targeted scientific evidence at the regional scale. This study aimed to explore the relationship between short-term environmental changes, including both meteorological conditions and air pollution, and RSV infection using a nationwide dataset encompassing all 16 Chilean regions. We fitted quasi-Poisson regression to assess the local-level estimates and used random effects meta-analyses to obtain national estimations. We further assessed the variations of such associations across different geographical and socio-economic contexts in Chile. Besides, we assessed the joint effects of high-level concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and fine particulate matter with a diameter smaller than 10 micrometers (\({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\)) on RSV activity. Our study provides insights to support cost-effective RSV prophylaxis strategies in Chile, such as seasonal RSV vaccination programs, thereby contributing to cost-effective disease control and prevention efforts (Fig. 1).

A Study population and key research components. Weekly RSV data from all 16 regions of Chile between 2015 and 2018 were included. This panel illustrates the research questions addressed in this study, including quantification of the spatial distribution of RSV activity, identification of the epidemic and non-epidemic seasons based on test positivity thresholds, and assessment of environmental exposures (meteorological factors and air pollutants) hypothesized to influence RSV activity. B Analytical workflow. This panel summarizes the statistical analyses conducted in the study. Correlation analyses characterize the distribution of environmental factors across epidemic and non-epidemic seasons and present nationwide correlation heatmaps to identify preliminary relationships with RSV activity. The two-stage association analysis consists of estimating region-specific associations using quasi-Poisson regression models, followed by pooling these regional estimates through meta-analysis to derive nationwide and subregional effects, to assess associations between environmental factors and RSV activity.

Results

Spatiotemporal characteristics of RSV infections

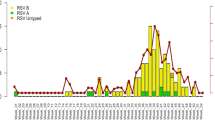

A total of 18,818 RSV cases were reported from 123,984 tests conducted across 16 regions of Chile, from January 2015 through December 2018. Of these cases, 61.4% (n = 11,557) occurred in infants (<1 year), and 31% (n = 5825) were in toddlers and preschool children (1–4 years), who were the most susceptible groups for RSV infections. Table 1 shows the summary statistics of RSV infections and environmental conditions in the 16 regions studied. Over the study period, we observed a mean of 5.7 newly lab-confirmed RSV-positive cases per week (standard deviation, SD = 12.9). Region-specific characteristics in 16 Chilean regions are presented in Supplementary Table S1. Over the study period, no significant spatial patterns were found regarding the annual test positivity rate of RSV (Table S2), indicating that RSV infections were randomly distributed across Chile. Figure 2 shows the spatial-temporal characteristics of RSV activity. In Chile, RSV epidemics started in June and ended in September. The RSV activity peaked first in toddlers and preschool children, followed by infants and elders. High activity of RSV, as measured by AAP, was observed in winter months, from June to August, in most regions.

A Time-series trends of RSV tests, detections, and positivity rate from 2015 to 2018, illustrating the epidemic cycles. Shaded areas denote epidemic seasons as defined by a 10% test positivity rate cutoff. B Time-series trends of age-specific weekly RSV confirmed cases in Chile, showing distinct seasonal patterns across age groups. Among them, the highest burden was consistently observed in children under 1 year of age, followed by those aged 1–4 years. Other groups exhibited lower burden and fewer variations in RSV activity over time. C Heatmaps showing the annual average percentage (AAP) of RSV infections across 16 Chilean regions from 2015 to 2018. The y-axis lists Chilean regions ordered by central latitude (negative values denote the Southern Hemisphere). Darker colors indicate higher RSV positivity, ranging from 0 to 100%. Dashed horizontal lines mark key latitudinal divisions: the Tropic of Capricorn, 30°S, and 40°S, highlighting spatial gradients in RSV activity.

Correlations between environmental factors and RSV activity

Figure 3 shows the correlations of weekly mean values of environmental factors and weekly RSV test positivity rate. At the national level, the weekly RSV test positivity rate was significantly correlated with other environmental factors, except for sulfur dioxide (\({{\rm{SO}}}_{2}\)), \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), and atmospheric pressure. At the regional level, across all 16 regions, the weekly RSV test positivity rate was positively correlated with \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\),\(\,{{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\), \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\), and relative humidity, while negatively correlated with average, maximum, and minimum temperature. Furthermore, statistically significant differences were observed between RSV epidemic and non-epidemic seasons for all environmental factors, except for \({{\rm{SO}}}_{2}\). Higher concentrations of air pollutants, except for ozone (\({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\)), along with increased wind speed, relative humidity, and lower temperatures, were found during RSV epidemics. Additionally, we found statistically significant differences in correlations between weekly RSV cases and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\), temperatures, and relative humidity among various age groups (Fig. S1). Higher correlations were found in children under 5 between air pollutants (\({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\)) and RSV infections, as well as between meteorological factors (temperatures and relative humidity) and RSV infections.

A Nationwide Spearman correlation between RSV test positivity rate and environmental factors (3-week prior), as well as correlations among environmental factors. Red shades indicate positive correlations, and blue shades indicate negative correlations. Darker colors denote stronger associations. Cells marked with “X” indicate nonsignificant correlations with two-sided p > 0.05. B Region-specific correlations between RSV test positivity rate and environmental factors (3-week prior). Colors range from red (positive) to blue (negative), with darker shades indicating stronger correlations. The dotted line separates regions located above and below the Tropic of Capricorn. C Distributions of environmental factors during epidemic and non-epidemic seasons defined using the 10% test positivity rate as a cutoff. Panel (1) shows air pollutants, and panel (2) shows meteorological factors. Grey box plots represent epidemic seasons, and yellow box plots represent non-epidemic seasons. ***denotes statistically significant differences between seasons assessed by the two-sided Mann–Whitney U test, and “ns” indicates nonsignificant differences where p > 0.05.

Nationwide associations between environmental factors and RSV activity

National estimates of the univariate associations between nine environmental factors and weekly RSV activity on different lag weeks are shown in Fig. 4, with region-specific estimates shown in Fig. S2. Similar lag patterns were observed for average temperature and minimum temperature. For every 1 °C increase in weekly average temperature, we observed a significant decrease in RSV positivity of 4.5% (95% CI: 0.92–0.99), 4.5% (95% CI: 0.91–1.00), and 8.2% (95% CI: 0.87–0.97) from lag 01 to lag 03, respectively. Among air pollutants, both \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) exhibited significant positive associations with elevated RSV positivity. Every 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentrations was associated with a 3.4% (95% CI: 1.00–1.06) significant increase in RSV positivity at lag 03. We observed consistent positive associations for \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), with every 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase associated with 5.4% (95% CI: 1.02–1.09), 8.3% (95% CI: 1.04–1.13), and 10.2% (95% CI: 1.05–1.15) significant increases in RSV positivity from lag 01 to lag 03, respectively. In addition, every 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase in concentrations of \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) was associated with a 4.4% (95% CI: 0.92–1.00), 7.7% (95% CI: 0.87–0.98), and 9.6% (95% CI: 0.84–0.97) significant decrease in RSV positivity from lag 01 to lag 03, respectively.

Relative risks (RRs) are presented for five meteorological variables and four air pollutants indicated by subtitles, with dashed horizontal lines indicating the reference value (RR = 1). For meteorological factors, estimates correspond to a 1-unit increase in exposure, whereas for air pollutants, estimates correspond to a 5-unit increase. Estimates are shown for the same week (lag 0), lagged effects up to 3 weeks (lags 1–3), and cumulative exposure over the previous 3 weeks (lag 01–03).

Table 2 presents the meta-regression results of significant effect modification on the univariate association between nine environmental factors (lag 03) and RSV activity by region-level environmental characteristics. The long-term background levels of wind speed and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) in regions modified the associations of relative humidity and RSV activity, indicating stronger associations in regions with lower annual average concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and higher annual average wind speed. We also found that associations between minimum temperature and RSV activity were stronger in regions with lower annual average wind speed, indicating wind speed is an important moderator for the effect of relative humidity and temperature on RSV activity. Additionally, we found that the associations between weekly maximum temperature and RSV activity were stronger in regions with higher weekly minimum temperature. The effect of other environmental factors on RSV activity was not modified by region-level environmental characteristics (in Supplementary Table S3).

Regionwide associations between environmental factors and RSV activity

Figure 5 illustrates the associations between nine environmental factors (lag 03) and RSV activity stratified by GDP per capita and location. Among these factors, weekly minimum temperature (p = 0.01) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentration (p = 0.01) showed significant heterogeneity in estimates across GDP strata. Minimum temperature was negatively associated with RSV test positivity in the top and lower-middle GDP groups, whereas \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) was positively associated with RSV test positivity in the top and upper-middle GDP groups. In addition, significant heterogeneity across latitudes, i.e., north (<30°S), central (30–35°S), and south (≥35°S), was observed for \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) (p = 0.03) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\,\)(p = 0.004). Specifically, in central Chile (30–35°S), higher concentrations of both pollutants were strongly associated with increased RSV positivity. A 5-µg/m3 increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) was associated with a 10% higher RSV positivity (95% CI: 1.05–1.14), while a 5-µg/m3 increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) was associated with a 5% higher positivity (95% CI: 1.03–1.07). Although heterogeneity across latitudes was not statistically significant for \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\), their effect estimates still varied by location. Similarly, the strongest associations were observed in central regions, where a 5-µg/m3 increase in \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) corresponded to a 14% higher RSV positivity (95% CI: 1.06–1.23), whereas a 5-µg/m3 increase in \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) was associated with a 15% lower positivity (95% CI: 0.78–0.92).

Estimations of relative risks (RRs) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are shown for five meteorological variables and four air pollutants, with the vertical dark red line indicating the reference value (RR = 1). For meteorological factors, estimates correspond to a 1-unit increase in exposure, whereas for air pollutants, estimates correspond to a 5-unit increase. Subgroup analyses stratified by GDP per capita and by latitude-based geographic regions are presented. P-values in subgroup rows refer to heterogeneity between subgroups, while P-values in the “overall” rows represent heterogeneity within the national scale.

Interactive effects between \({{\bf{PM}}}_{{\bf{2.5}}}\) and \({{\bf{PM}}}_{{\bf{10}}}\) on RSV activity

We further examined the joint effects of high concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) on RSV activity. Nationwide and region-specific estimates are presented in Fig. 6. No significant joint effects were observed at the national level for the interaction between \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) across various thresholds. Positive interactions between high concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) (>90th percentile) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) (>90th percentile) were observed, with an estimated relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI) of 0.09 (95% CI: −0.29–0.46). Differences in joint-effect estimates across GDP strata were statistically significant between high concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) (>90th percentile) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) (>90th percentile) (P = 0.003). A significant pooled synergistic effect was observed in the upper-middle GDP strata, with an estimated RERI of 0.86 (95% CI: 0.26–1.45). Although heterogeneity across latitude categories was not statistically significant (all P > 0.05), effect estimates varied by location. In central Chile, we observed positive interactions between high concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) (>90th percentile) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) (>90th percentile), with a RERI of 0.26 (95% CI: −0.74–1.27), albeit not statistically significant.

Results are presented as relative excess risks due to interaction (RERI) with 95% confidence intervals across increasing quantiles of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) exposure (60th, 70th, 80th, and 90th). The vertical dark red line indicates the reference value (RERI = 0). Subgroup analyses stratified by GDP per capita and by latitude-based geographic regions are presented. P-values in subgroup rows refer to heterogeneity between subgroups, while P-values in the “overall” rows represent heterogeneity within the national scale.

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of our findings. The epidemic season remained stable when the 10% cutoff was replaced with 5%, 7.5%, and 12.5% (Table S4). Likewise, the statistically significant differences in environmental conditions between epidemic and non-epidemic seasons persisted across all alternative thresholds (Tables S5 and 6). When model specifications were varied, the estimates remained robust. Nationwide estimates remained stable when the degrees of freedom for the lag-response curve were changed from 3 to 4. Incorporating spatial structure into the regression models also produced robust estimates with overlapping confidence intervals, although they were slightly more conservative (Fig. S3). Results remained consistent when the lag period was extended to five weeks (Fig. S4). Moreover, findings were consistent when the study period was extended to 2019 for 15 regions (excluding Aysén) and when the analysis was restricted to the specific periods (April to September) (Fig. S3). Likewise, the effect estimates were robust when missing data were imputed using Kriging interpolation (Fig. S5).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the role of short-term changes in both meteorological factors and air pollutants with RSV activity in Chile, exploring consistency and local variations under different backgrounds, including geographical, socio-economic, and environmental contexts. We observed a nationwide negative association between weekly average temperature and RSV infections at lags 01–03. In contrast, air pollutants such as \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) showed positive nationwide associations across multiple lag periods. A 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) concentrations was positively associated with increases in RSV positivity of 3.4% (1.00–1.06) and 10.2% (1.05–1.15) at lags of 3 weeks, respectively. National-level evidence linking environmental factors to RSV activity has been reported in other settings, including our previous study in Japan13. However, this work extends the current literature by assessing spatial and socio-economic variation across regions of these relationships. The strength of the associations differed across regions with varying annual average levels of environmental conditions. Notably, stronger associations between \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) and RSV infections were observed in central regions (RR: 1.05, 95% CI: 1.03–1.07), where higher levels of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) exposure occurred during the RSV season. These findings deepen the understanding of local variations in RSV activity and its associated environmental drivers, providing insights to support regionally tailored timing of seasonal prophylaxis strategies. Overall, this work suggests that short-term spikes in air pollution levels, especially for \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), may elevate RSV activity for up to three weeks, although the effect sizes remain modest. Furthermore, action on potentially modifiable factors like air pollutants beyond particulate matter may substantially reduce RSV activity across all age groups.

RSV exhibits a clear seasonal pattern in Chile, prevalent during the winter months from June to September. Correspondingly, we observed consistent nationwide positive associations between RSV infection and lower average temperatures across multiple lag periods. Although Chile spans diverse geographic and climatic regions, the regional pooled estimates did not differ significantly. However, regionally, lower temperatures were positively associated with increased RSV risk only in southern Chile. Existing evidence has demonstrated that RSV seasonality and its meteorological drivers vary by geographical location7. In tropical settings, high temperature generally occurs with high humidity, potentially influencing human behaviors, particularly the preference for indoor activities in air-conditioned (AC) environments14. The recirculated air and closer interpersonal interactions in such indoor settings potentially facilitate virus spread15. In contrast, RSV activity in temperate regions is strongly linked to colder weather. Temperature influences the stability and transmission of respiratory viruses through effects on structural components (e.g., lipid membranes, surface proteins) and functional processes (e.g., replication enzymes)16. As an enveloped virus, RSV can survive longer at lower temperatures. Increasing temperature may increase lipid mobility, destroy envelope integrity, and reduce infectivity, explaining why the prevalence of RSV often occurs in winter seasons16. Similar patterns of regional variation have been reported in China. Wang et al.17 found that in northern China, low temperatures increased the risk of influenza A virus (Flu A), whereas in central and southern China, both low and high temperatures increased that risk. These findings highlight the need for countries spanning multiple climatic zones to account for regional variability when assessing meteorological influences on virus transmission and to formulate tailored prevention and control strategies accordingly.

We estimated a 10% decrease in RSV positivity associated with a 5-μg/m3 increase in \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) concentrations at lag 03. Although the association between \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) concentrations and RSV activity has been documented in several countries, epidemiological findings remain inconsistent18. Consistent with our results, a study conducted in an urban area of Italy reported a negative correlation between \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) levels and RSV-related bronchiolitis19. Similarly, research in China found that RSV test positivity rates were inversely associated with monthly maximum 8-h ozone concentrations20. In contrast, a Canadian study reported a positive association between elevated \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) levels and RSV hospitalizations21. Meanwhile, studies from Singapore and Colombia found no significant relationship between \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) levels and RSV detection22,23. In our study, we found that \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) levels peaked in spring-summer (October-February), whereas RSV activity peaked in winter (June–September). This seasonal variation likely contributed to the inverse correlation observed in the weekly data and may partially explain the observed negative association between \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) and RSV activity. When we restricted the regression analyses to the RSV season, the negative association between higher O3 levels and RSV activity remained, although it was no longer statistically significant. Further investigation into the biological mechanisms by which \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) concentrations may influence respiratory viral pathways is warranted to help clarify this relationship.

Consistent with previous evidence12, this study shows that air pollution, particularly \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\), is positively linked to RSV infections in Chile. Subgroup analyses reveal regional variation in these associations. Every 5-\({\rm{\mu }}{\rm{g}}/{{\rm{m}}}^{3}\) increase in \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentrations was significantly associated with a 10% increase in RSV positivity in central Chile, whereas no similar pattern was observed in other areas. Central Chile has a substantially higher population density24, which may contribute to the stronger associations observed. Supporting this, an epidemiological study from New Zealand reported that population density was linked to poorer air quality and worse health outcomes, with adverse effects of \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and respiratory hospitalizations related to \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) increasing progressively with urban density25. Meanwhile, this discrepancy may be explained by regional differences in air pollution levels. During winter, the RSV epidemic season, \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentrations in central and southern Chile are markedly higher than in the north. In other seasons, less pronounced differences in the \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentration were observed, with slightly higher concentrations in northern Chile likely due to emissions from the concentrated mining industry. Residential wood-burning for heating may explain the sharply increased concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) in central and southern Chile during winter26. Air pollution problems caused by residential wood combustion have been widely reported in Chile, especially in southern and central regions27. Severe ambient air pollution causes substantial health impact, leading to increased morbidity and mortality from respiratory and cardiovascular diseases28. Our findings align with a previous study in Temuco29, which found that household air pollution from wood burning was associated with an increased risk of lower respiratory tract infections in children. Additionally, a meta-analysis identified that household air pollution caused by biomass fuel usage has become one of the main risk factors for respiratory diseases in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs)30. In Africa, household \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) pollution was significantly correlated with age-standardized disability-adjusted life years caused by lower respiratory tract infections31. Our results suggest that elevated \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) concentrations, potentially driven by residential wood-burning heating activity, are associated with increased RSV positivity in central and southern Chile. Further research on household air pollution and respiratory health is essential for informing effective interventions to improve respiratory health in highly polluted regions, including but not limited to LMICs.

Although previous studies have reported the individual effects of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) on RSV infection10,32, their joint impact remains underexplored. Our analysis addresses this gap and shows that in central and southern Chile, concurrent high concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) showed synergistic, though not statistically significant, elevations in RSV positivity, whereas no similar effect was observed in the north. Similarly, such regional differences are likely attributable to the substantially higher particulate matter levels in central and southern Chile during winter, potentially driven by residential heating activities. The negative effects of particulate matter (including \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\), \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\), and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{0.1}\)) on respiratory health are well assessed33. When RSV is harbored by \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\), it triggers greater secretion of pro-inflammatory mediators (IL-6 and IL-8) by respiratory epithelial cell cultures than the same dose of RSV alone34. Additionally, particle attachment can enhance the survival rate of the virus, potentially facilitating the community spread of RSV34. Besides, \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) can induce an aberrant cell cycle through the overexpression of microRNA-155 (miR-155), contributing to the susceptibility to pathogens35. Synergistic effects between long-term \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) exposure and other pollutants (e.g., \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\)) on respiratory mortality have likewise been reported36. Our findings further emphasize the potential synergistic impact of two air pollutants on RSV infection. Further research is warranted to investigate the interactive effects of multiple environmental factors, such as extreme weather and high-level concentrations of air pollution, on RSV infection.

Obtaining accurate exposure assessments remains one of the pressing challenges in environmental health research37. In this study, we used air quality data from ground monitoring stations in the National Air Quality Information System (SINCA), managed by the Chilean Ministry of Environment. During the study period, several regions lacked monitoring sites for specific pollutants, particularly \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\) and \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\). Generally, satellite-based products are commonly used to address sparse or uneven monitoring coverage38. Increasingly in recent years, meteorological satellite data have been applied to model the spatial and seasonal dynamics of infectious disease transmission37. However, their applicability for air pollution exposure assessment in South America is limited because (1) they provide column-averaged tropospheric rather than surface-level concentrations, and (2) they offer values at a low spatial resolution39. Given these constraints, we continued using the ground monitoring data from SINCA and imputed missing values using two geostatistical methods, i.e., inverse distance weighting (IDW) and kriging interpolation, to reduce the uncertainty of our results due to imputing missing data. IDW served as the primary approach due to the uneven distribution of monitoring stations, while kriging was evaluated in sensitivity analyses. Nationwide pooled estimates for \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\), and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) were consistent across both interpolation methods, supporting the robustness of our findings. Nevertheless, these results should be interpreted with caution, and further research is needed to validate and extend these conclusions.

Currently, many studies have applied two-step time-series analyses to examine the relationship between environmental factors and health outcomes, particularly for non-communicable diseases such as stroke and cardiovascular disease40,41. This approach involves (1) fitting region/city-specific time-series models and (2) pooling the region/city-specific estimates through meta-analyses to generate national or broader-scale effects. Similarly, in our study, we adopted a two-step time-series framework as the primary analytical approach, given the absence of spatial dependence in RSV transmission in Chile between 2015 and 2018. However, the transmission dynamics of infectious diseases differ substantially from those of non-communicable diseases. Zheng et al. found that the RSV epidemic spread follows a spatial diffusion process based on geographic proximity42. Accordingly, in our sensitivity analyses, we incorporated neighboring RSV activity into the region-specific models to account for potential spatial dependence. The resulting estimates were similar to those from the main analysis, likely reflecting the absence of spatial structure in our data. This also indicates that adding spatial structure does not obscure environmental signals and underscores the robustness of spatially informed modeling in infectious disease research. Future work could extend these analyses using principled Bayesian spatial structures, such as conditional autoregressive priors, which may be particularly relevant for infectious diseases with clear spatial diffusion patterns, including influenza and COVID-19, in densely populated settings.

Our epidemiological study included more than 120,000 RSV laboratory tests and 18,000 RSV lab-confirmed cases across 16 Chilean regions. We applied a consistent statistical method across the regions, enhancing the internal comparison of findings across these cities and the external comparison with the results of other studies. Therefore, our study offers generalized evidence supporting the effects of short-term changes in environmental factors on RSV infection. Seasonal winter RSV epidemics place a substantial burden on Chile’s healthcare system. In response, Chile introduced a nationwide, Nirsevimab-based seasonal immunization program in 2024 to mitigate this impact6. A recent observational study estimated the effectiveness of over 75% prevention against RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection hospitalizations and RSV-related intensive care unit admissions6. Our work further clarifies the spatiotemporal patterns of RSV activity, providing essential evidence on RSV seasonality for optimizing immunization timing and improving cost-effectiveness. Furthermore, by identifying regional variations in the environmental drivers of RSV circulation, this work offers evidence to support regionally tailored seasonal prophylaxis strategies.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our study was based exclusively on pre-pandemic data (2015–19). The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted typical circulation patterns and seasonal dynamics of many respiratory viruses, including RSV, which has now largely returned to the pre-pandemic patterns43. Therefore, the generalizability of our model to the immediate post-pandemic period (2021–23) should be done with caution. Second, our study elucidated the lagged effects of environmental factors on RSV activity in Chile. However, this analysis did not establish any causal effects of environmental factors on RSV activity. Third, our study did not examine age-specific differences in the associations between environmental factors and RSV infections, as age-specific test numbers were unavailable. Nonetheless, we observed significant differences in the correlations between RSV cases and environmental factors across age bands. Future studies that incorporate age-specific testing data are needed. In addition, we acknowledge that using test behavior as an offset may not fully eliminate bias, given potential regional differences in catchment populations, the number of hospitals included, and surveillance practices. Fifth, we acknowledge that heterogeneity in the monitoring-network density may introduce some bias. To mitigate this, we combined station averaging with spatial interpolation and demonstrated that our estimates were robust across different imputation approaches. Additionally, external validation is needed to assess the applicability of our analytical framework in other settings. Despite sensitivity analyses supporting the robustness of our framework, its generalizability to areas outside Chile remains untested. Furthermore, we did not explore the role of extreme weather events in RSV transmission, despite evidence showing that cold spells may influence respiratory health44. Moreover, the study may have overlooked the complex interactions among environmental factors. Except for the joint analysis of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\), we applied univariate models to assess the independent effects of short-term environmental changes. This may have overlooked complex interactions, particularly between extreme weather events and elevated \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) levels45, which are known to have significant effects on respiratory health.

This national study in Chile identified associations between short-term environmental changes and RSV activity. Furthermore, it highlights the importance of accounting for regional differences when assessing environmental impacts on RSV transmission. Our findings support the development of cost-effective strategies for RSV prophylaxis in Chile, especially in formulating region-specific prevention and control strategies, contributing to effective disease control and prevention efforts.

Methods

Data collection

We collected weekly RSV information provided by the Public Health Institute of Chile between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019. The weekly number of laboratory tests and laboratory-confirmed positive cases without age limitation were extracted from 31 public hospitals in 16 administrative regions in Chile. An immunofluorescence assay was used to detect the presence of RSV in nasopharyngeal aspirates in Chile during the study period.

Daily meteorological and air pollutant data were extracted between January 1, 2015, and December 31, 2019. Daily mean temperature (°C), maximum temperature (°C), minimum temperature (°C), total precipitation (mm), and hourly metrics of wind speed (m/s), atmospheric pressure (hPa), and relative humidity (%) were retrieved from the Meteorological Directorate of Chile (D.M.C.). Air pollution data, including daily mean concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5},\) \({\rm{P}}{{\rm{M}}}_{10}\), \({\rm{S}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}\), \({\rm{N}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}\), and \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) were extracted from observational stations in 16 Chilean regions from National Air Quality Information System (SINCA). The missing daily observations were imputed and subsequently aggregated at the region level (details in Supplementary File p4). We restricted our main analyses to data from 2015 through 2018 to preserve the integrity of our study, since no confirmed positive cases were found in Aysén in 2019.

Statistical analyses

Weekly test positivity rates (%), both nationwide and at the regional level for Chile, were calculated from 2015 through 2018. Epidemic seasons were defined using the test positivity rate threshold method, with a 10% cutoff selected since it is commonly used for defining RSV epidemic seasons46. Moran’s I statistic was calculated to evaluate the spatial pattern of RSV transmission in Chile from 2015 through 2018. We calculated the monthly annual average percentage (AAP) to measure the relative strength of RSV activity by the formula,

where i denotes the month and N denotes the number of cases. Heat maps were employed to display RSV activity in 16 regions sorted by latitude.

Considering the incubation period of RSV infections (2–8 days), we applied Spearman’s correlation coefficient (two-sided) to examine the correlations between environmental conditions with a 3-week prior and RSV test positivity rate at both national and regional level in Chile. Age-stratified correlations between environmental conditions with a 3-week prior and RSV cases were examined at the regional level. Two-sided Kruskal–Wallis tests were applied to assess statistically significant differences in correlations among age groups. Additionally, two-sided Mann–Whitney U tests were used to examine statistically significant differences in the distribution of environmental factors between epidemic seasons and non-epidemic seasons.

We applied a two-step time-series analytical approach to estimate the regional and national associations between environmental conditions and weekly RSV infections. All environmental factors were included in the regression analyses except for precipitation and \({\rm{S}}{{\rm{O}}}_{2}\), according to the correlation analysis results. In the first stage, for 16 regions, we fitted univariate quasi-Poisson regressions in a distributed lag non-linear model (DLNM) for 9 environmental factors, respectively, allowing for overdispersion in RSV infection numbers to obtain region-specific estimates.

The \({Y}_{\mathrm{itk}}\) is the number of RSV cases at week \({\rm{t}}\) in year \({\rm{k}}\) in region \({\rm{i}}\). We assumed that \({Y}_{\mathrm{itk}}\) follows a Poisson distribution, e.g., \({Y}_{\mathrm{itk}} \sim \mathrm{Pois}\left({\lambda }_{\mathrm{itk}}\right)\), where \({\lambda }_{\mathrm{itk}}\) is the expected mean of \({Y}_{\mathrm{itk}}\). In our models, we considered an extended version of Poisson regression, the quasi-Poisson regression, to solve the overdispersion issue, where \({Y}_{\mathrm{itk}} \sim \mathrm{quasi}-\mathrm{Poisson}\left({\lambda }_{\mathrm{itk}},\phi \right)\). The \(f\left(\mathrm{factor},\mathrm{lag}\right)\) measures the lagged effect of an individual environmental factor on RSV cases up to 3 weeks in a univariate model. The cross-basis functions were composed of a linear exposure-response relationship and a polynomial regression in a lag-response relationship with 3 degrees of freedom (df). All models were adjusted for weekly testing numbers as an offset. All models were only adjusted for temporal variations, as no spatial dependence was observed. Specifically, a smooth spline function of calendar month was incorporated into the models to adjust for seasonality and long-term trends. Besides, several confounding covariates were incorporated according to previously published evidence, using natural cubic spline functions with 3 df. For meteorological factors, we controlled for the effects of atmospheric pressure as a covariate. For air pollutants, we controlled for the effects of wind speed, relative humidity, and average temperature. The maximum lag period was set as 3 weeks in this study, accounting for the incubation period of RSV, the time from symptom onset to diagnostic testing, and potential delays in case reporting47. We estimated the effects of environmental factors for the same week (lag 0) and the lagged effects up to 3 weeks (lag 1, lag 2, and lag 3), as well as for cumulative exposure over the previous 3 weeks (lag 01–lag 03). Region-specific \(25^{\mathrm{th}}\) percentiles of each environmental variable from 2015 to 2018 were used as the reference values, accounting for the substantial variation in environmental conditions across Chile.

Additionally, we calculated the RERI as a metric to evaluate the region-specific joint effect of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) in Chile at lag 3. We dichotomized continuous concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) into binary variables (Table S7). We calculated the \(60^{\mathrm{th}}\), \(70^{\mathrm{th}}\), \(80^{\mathrm{th}}\), and \(90^{\mathrm{th}}\) percentiles of the weekly average concentrations of \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\) from 2015 to 2018 as thresholds.

The relative risks were computed from the regression coefficient estimates, which are denoted by \({{\rm{RR}}}_{10}\)(only excessive \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\)), \({{\rm{RR}}}_{01}\)(only excessive \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\)), and \({{\rm{RR}}}_{11}\)(joint excessive \({{\rm{PM}}}_{2.5}\) and \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\)) for the relative risk, respectively.

In the second stage, we used random effects meta-analyses to pool the region-specific estimates over the lag period at the national level. Stratified analyses by GDP per capita and geographical locations were conducted for individual effects at lag 03 and RERI at lag 3. We categorized the 16 Chilean regions into 4 groups based on the GDP per capita in 2014 from highest to lowest, as top (0–25%), upper-middle (25–50%), lower-middle (50–75%), and bottom (75–100%). Considering the substantial difference in environmental conditions in Chile, we divided regions into northern (17–30°S), central (30–35°S), and southern (35–60°S) regions, separated by the latitudes of 30° and 35°. We also fitted meta-regression models to assess whether region characteristics would modify RSV activity in relation to short-term changes in environmental conditions. The region characteristics included the region-specific annual average of weekly environmental factors from 2015 through 2018, including 5 meteorological factors and 4 air pollutants.

Sensitivity analyses

A series of sensitivity analyses was undertaken to assess the robustness of the results. To ensure the stability of epidemic season-stratified descriptions, we applied alternative test positivity thresholds of 5%, 7.5%, and 12.5% to define epidemic seasons. We then examined the sensitivity of the effect estimates to model specification. We checked whether the estimates were robust to the changes in the degrees of freedom for the lag-response (df = 4) curve. We further extended the lag period of environmental variables up to 5 weeks to examine the stationarity of lag-response structures. To assess temporal consistency, we repeated the analyses using 5-year data (2015–2019) for 15 regions, excluding Aysén. Instead of analyzing the full calendar year, we restricted the analysis to the RSV season (April–September), corresponding to the period of high virus prevalence, to address potential seasonal confounding. Additionally, we assessed the potential influence of spatial dependence by incorporating spatial structure into the regression models, including weekly test positivity in contemporaneous and preceding three weeks from neighboring regions. Finally, to assess uncertainty arising from interpolating missing data, we applied kriging interpolation to estimate \({{\rm{NO}}}_{2}\), \({{\rm{PM}}}_{10}\), and \({{\rm{O}}}_{3}\) in regions without air quality stations and compared nationwide pooled estimates with those from the main analyses.

We conducted statistical and sensitivity analyses using R software version 4.2.1. The dlnm48 and sp49 packages were used to develop the regression model. The metafor50 package was used to pool region-specific estimates. The relative risks (RR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were reported. All tests were two-sided with \(\alpha\) = 0.05.

Data availability

Publicly available data is found here: meteorological data can be downloaded from the Meteorological Directorate of Chile (https://climatologia.meteochile.gob.cl/), and air pollution data can be downloaded from National Air Quality Information System (SINCA) (https://sinca.mma.gob.cl/). RSV data from the Public Health Institute of Chile used in this study are available through the GitHub repository with restricted access: https://github.com/jingyi1009/Short-term-environmental-changes-and-respiratory-syncytial-virus-infection-in-nationwide-Chile. We are currently in communication with the data provider to explore the possibility of making these data publicly available. This process may take some time, but we are actively working on it.

Code availability

Codes utilized for analyses have been made available through the GitHub repository: https://github.com/jingyi1009/Short-term-environmental-changes-and-respiratory-syncytial-virus-infection-in-nationwide-Chile.

References

Li, Y. et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in children younger than 5 years in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 2047–2064 (2022).

Savic, M., Penders, Y., Shi, T., Branche, A. & Pirçon, J. Y. Respiratory syncytial virus disease burden in adults aged 60 years and older in high-income countries: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 17, e13031 (2023).

Sauré, D. et al. Cost-savings and health impact of strategies for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus with nirsevimab in Chile based on the integrated analysis of 2019–2023 national databases: a retrospective study. J. Infect. Public Health 18, 102680(2025).

Obando-Pacheco, P. et al. Respiratory Syncytial Virus Seasonality: A Global Overview. J Infect. Dis. 217, 1356–1364 (2018).

Tapia, L. I. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and recurrent wheezing in Chilean infants: a genetic background? Infect. Genet. Evol. 16, 54–61 (2013).

Torres JP, et al. Effectiveness and impact of nirsevimab in Chile during the first season of a national immunisation strategy against RSV (NIRSE-CL): a retrospective observational study. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(25)00233-6 (2025).

Ye, S. et al. Understanding the local-level variations in seasonality of human respiratory syncytial virus infection: a systematic analysis. BMC Med. 23, 55 (2025).

Li, Y. et al. Global patterns in monthly activity of influenza virus, respiratory syncytial virus, parainfluenza virus, and metapneumovirus: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob. Health 7, e1031–e1045 (2019).

Wrotek, A. et al. Air pollutants’ concentrations are associated with increased number of RSV hospitalizations in Polish children. J. Clin. Med. 10, 3224 (2021).

Zhi, W. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in children and its correlation with climatic and environmental factors. J. Int. Med. Res. 49, 03000605211044593 (2021).

YUSUF, S. et al. The relationship of meteorological conditions to the epidemic activity of respiratory syncytial virus. Epidemiol. Infect. 135, 1077–1090 (2007).

PM, C. & MO, G. Impacto del material particulado aéreo (MP2,5) sobre las hospitalizaciones por enfermedades respiratorias en niños: estudio caso-control alterno. Andes Pediatr. 90, 166–174 (2019).

Liang, J., Luz, S., Li, Y. & Nair, H. Associations between environmental conditions and infection with Respiratory Syncytial Virus in Japan: a spatiotemporal analysis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 12, ofaf392 (2025).

PAYNTER, S. Humidity and respiratory virus transmission in tropical and temperate settings. Epidemiol. Infect. 143, 1110–1118 (2015).

Tang, J. W. & Loh, T. P. Correlations between climate factors and incidence—a contributor to RSV seasonality. Rev. Med. Virol. 24, 15–34 (2014).

Shang, X. et al. Global meta-analysis of short-term associations between ambient temperature and pathogen-specific respiratory infections, 2004 to 2023. Eur. Surveill. 30, 2400375 (2025).

Wang, D., Lei, H., Wang, D., Shu, Y. & Xiao, S. Association between temperature and influenza activity across different regions of China during 2010–2017. Viruses 15, 594 (2023).

Wrotek, A. E., Badyda, A. & Jackowska, T. Time-dependent, cumulative and threshold effects of air pollution – RSV interaction: a narrative review. Pediatr. Pol. 99, 194–202 (2024).

Nenna, R. et al. Respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis, weather conditions and air pollution in an Italian urban area: an observational study. Environ. Res. 158, 188–193 (2017).

Luo, X.-P. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children in Nanchang and its correlation with climate environmental factors. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 26, 1282–1287 (2024).

Radhakrishnan, D. et al. The association between climate, geography and respiratory syncitial virus hospitalizations among children in Ontario, Canada: a population-based study. BMC Infect. Dis. 20, 157 (2020).

Lee, M. H. et al. Air quality, meteorological variability and pediatric respiratory syncytial virus infections in Singapore. Sci. Rep. 13, 1001 (2023).

Villamil-Osorio, M. et al. Multilevel analysis identifying the factors associated with RSV detection in infants admitted for viral bronchiolitis in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 58, 2795–2803 (2023).

Gallardo L, et al. Evolution of air quality in Santiago: the role of mobility and lessons from the science-policy interface. in (eds Helmig, D. and von Schneidemesser, E.) Elementa: Science of the Anthropocene Vol 6, 38 (UC Press, 2018).

Wrightson, S., Hosking, J. & Woodward, A. Higher population density is associated with worse air quality and related health outcomes in Tāmaki Makaurau. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 49, 100213 (2025).

Schueftan, A., Sommerhoff, J. & González, A. D. Firewood demand and energy policy in south-central Chile. Energy Sustain. Dev. 33, 26–35 (2016).

Quinteros, M. E. et al. Spatio-temporal distribution of particulate matter and wood-smoke tracers in Temuco, Chile: a city heavily impacted by residential wood-burning. Atmos. Environ. 294, 119529 (2023).

Busch, P., Cifuentes, L. A. & Cabrera, C. Chronic exposure to fine particles (PM2.5) and mortality: evidence from Chile. Environ. Epidemiol. 7, e253 (2023).

Rey-Ares, L. et al. Lower tract respiratory infection in children younger than 5 years of age and adverse pregnancy outcomes related to household air pollution in Bariloche (Argentina) and Temuco (Chile). Indoor Air 26, 964–975 (2016).

Hu, J., Zhou, R., Ding, R., Ye, D. W. & Su, Y. Effect of PM2.5 air pollution on the global burden of lower respiratory infections, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. J. Hazard. Mater. 459, 132215 (2023).

Jafta, N., Shezi, B., Buthelezi, M., Muteti-Fana, S. & Naidoo, R. N. Household air pollution and respiratory health in Africa: persistent risk and unchanged health burdens. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 31, 89 (2025).

Wrotek, A. et al. Air pollutants exposure and risk of hospitalization due to RSV in Polish children. Eur. Respir. J. 62, https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.congress-2023.PA2726 (2023).

Loaiza-Ceballos, M. C., Marin-Palma, D., Zapata, W. & Hernandez, J. C. Viral respiratory infections and air pollutants. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 15, 105–114 (2022).

Cruz-Sanchez, T. M. et al. Formation of a stable mimic of ambient particulate matter containing viable infectious respiratory syncytial virus and its dry-deposition directly onto cell cultures. Anal. Chem. 85, 898–906 (2013).

Xiao, T. et al. NF-κB-regulation of miR-155, via SOCS1/STAT3, is involved in the PM2.5-accelerated cell cycle and proliferation of human bronchial epithelial cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 377, 114616 (2019).

Mainka, A. & Żak, M. Synergistic or antagonistic health effects of long- and short-term exposure to ambient NO2 and PM2.5: a review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19, 14079 (2022).

Patz, J. Guest editorial: satellite remote sensing can improve chances of achieving sustainable health. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, A84–A85 (2005).

Tian, Y. et al. Advancing application of satellite remote sensing technologies for linking atmospheric and built environment to health. Front. Public Health. 11, 1270033 (2023).

Mardoñez-Balderrama, V. et al. Health impacts of air pollution in South America: recent advances and research gaps. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 45, 100627 (2025).

Tian, Y. et al. Association between ambient air pollution and daily hospital admissions for ischemic stroke: A nationwide time-series analysis. PLoS Med 15, e1002668 (2018).

Chen, R. et al. Associations between ambient nitrogen dioxide and daily cause-specific mortality: evidence from 272 Chinese cities. Epidemiology 29, 482 (2018).

Zheng, Z., Pitzer, V. E., Warren, J. L. & Weinberger, D. M. Community factors associated with local epidemic timing of respiratory syncytial virus: a spatiotemporal modeling study. Sci. Adv. 7, eabd6421 (2021).

Chow, E. J., Uyeki, T. M. & Chu, H. Y. The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on community respiratory virus activity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 21, 195–210 (2023).

Sario, M. D., Katsouyanni, K. & Michelozzi, P. Climate change, extreme weather events, air pollution and respiratory health in Europe. Eur. Respir. J. 42, 826–843 (2013).

Ning, Z. et al. The interactive effect of extreme weather events and PM2.5 on respiratory health among the elderly: a case-crossover study in a high-altitude city. Int. J. Biometeorol. 69, 331–342 (2025).

Chadha, M. et al. Human respiratory syncytial virus and influenza seasonality patterns-Early findings from the WHO global respiratory syncytial virus surveillance. Influenza Other Respir. Viruses 14, 638–646 (2020).

Manti, S. et al. Detection of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) at birth in a newborn with respiratory distress. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 52, E81–E84 (2017).

Gasparrini, A., Armstrong, B. & Scheipl, F. dlnm: distributed lag non-linear models. Published online October 7, 2021. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dlnm/index.html.

Pebesma, E. et al. sp: classes and methods for spatial data. Published online April 30, 2024. Accessed August 6, 2024. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/sp/index.html.

Viechtbauer, W. metafor: meta-analysis package for R. Published online January 28, 2025. Accessed May 7, 2025. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metafor/index.html.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.N. and J.L. conceived the study. H.N. supervised the work. J.L. led the data analysis and interpretation, with substantial input from H.N., R.F., Y.L., and S.L. J.L. and R.F. accessed and verified the data, and R.F. had full access to all data in the study. J.L. drafted the manuscript. All authors provided critical revisions to the manuscript, approved the final version, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Patient Consent Statement

This research does not include factors necessitating patient consent.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, J., Fasce, R., Luz, S. et al. Short-term environmental changes and respiratory syncytial virus infection in Chile. npj Clean Air 2, 7 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-026-00049-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44407-026-00049-6