Abstract

Although X‑rays revolutionized diagnostics, their health risks and lead shields’ toxicity and environmental hazards demand safer, practical wearable alternatives. Bismuth, a non-toxic element with a high atomic number, has emerged as a promising candidate for radiation shielding applications. Recent efforts to develop Bi‑compound/polymer soft shields are limited by the polymer’s low attenuation and its low‑Z non‑Bi components. In this study, we introduce a fully metallic, non-toxic, and soft material composed of gallium, indium, and bismuth particles for wearable X-ray protection. Through careful compositional tuning and processing, we successfully achieved a room-temperature soft material with excellent mechanical flexibility and strong X-ray attenuation performance. Both theoretical calculations and experimental measurements confirmed the composite’s high shielding efficiency. Furthermore, the material exhibited strong adhesion and conformability when applied to textile substrates. These results highlight the promise of this material as a soft, non-toxic, and wearable solution for X-ray radiation protection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

X-rays possess excellent penetration ability and are vital tools in medical diagnostics. X-ray imaging has driven advancements in technologies such as diagnostic radiography, mammography, radiotherapy, and computed tomography (CT), and the resulting imaging information is essential for diagnosis and guiding surgical procedures1. However, X-rays can easily penetrate the human body and ionize organ tissues. They directly break the bonds between atoms in genes, and not all damaged genes are properly repaired after high-dose exposure, leading to various health-related issues such as autonomic nerve dysfunction, lens opacities, and cellular damage2,3,4. Moreover, under high-dose exposure, such as during radiation therapy, patients often experience side effects such as radiation dermatitis5,6. Therefore, both healthcare workers and patients need lightweight, flexible, and wearable shielding materials to serve as a protective skin barrier.

To mitigate such exposure, a wide range of radiation-shielding materials has been explored. Ionizing radiation absorption primarily depends on the atomic number (Z) and density (ρ) of the shielding material. Lead-based materials are a traditional choice for radiation-shielding due to their high atomic number (ZPb = 82) and density (ρPb = 11.34 g/cm3)7,8. However, lead-based materials pose serious health risks, making them unsuitable for direct use on the skin as a shielding agent9,10.

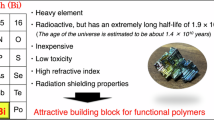

To overcome the limitations of traditional lead-based materials, bismuth (Bi, ZBi = 83, ρBi = 9.78 g/cm3) has emerged as a promising alternative due to its effective shielding ability and non-toxic9. Despite these advantages, Bi is inherently brittle, and its lack of flexibility either in bulk or plate form limits its suitability for wearable applications11. To address this issue, recent advances have focused on incorporating Bi particles into polymer matrices to create flexible composites. For instance, Jagdale et al. prepared a bismuth oxychloride nanoplate (BiOCl NPs)-polymer composite by dispersing 2 wt% BiOCl NPs into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) matrix12. Thumwong et al. added nano-bismuth(III) oxide (Bi2O3) to natural rubber latex to fabricate a radiation-shielding composite13. Azman et al. electrospun n-ZnO/n-Bi2O3/epoxy-polyvinyl alcohol nanofiber mats containing 0–20 wt% n-zinc oxide (ZnO) and 1 wt% n-Bi2O3 fillers14. Dincer et al. embedded bismuth tin (BiSn) core-shell particles into thermoplastic polyurethane matrix to create wearable X-ray shielding materials15. While these Bi-based composites offer improved flexibility, their overall shielding efficiency remains limited due to the low attenuation performance of polymer matrices16. High atomic number and high-density metallic elements have also been explored for enhanced radiation shielding. However, most existing efforts focus on Bi-Sn or Bi-In-Sn alloys, which involve complex alloying procedures and lack flexibility at room temperature17.

In this study, we report the development of a tunable Gallium/Indium (Ga/In)-Bi composite material for soft and wearable radiation shielding (Fig. 1a), leveraging the exceptional softness and shielding functionality of Ga/In-based liquid metal and Bi. A soft composite was developed at room temperature with up to 35 wt% Bi incorporated into a Ga/In matrix. The developed Ga/In-Bi composite exhibits tunable phases and can achieve a soft form at specific composition ratios. As shown in Fig. 1b, this soft composite provides excellent mechanical flexibility, with the composite remaining intact under repeated bending deformation. Moreover, the composite enables uniform and conformal coating onto textile substrates, making it suitable for wearable applications. To realize a practical implementation, the composite can be conformally applied to cotton gloves and encapsulated with hydrophilic polyurethane (HPPU) via dip-coating (Fig. 1c, d). Its X-ray attenuation performance was evaluated using an Empyrean X-ray diffractometer, which demonstrated a maximum linear attenuation coefficient (μ) of 1327 cm−1 at 8.04 keV, significantly higher than that of Bi-based polymeric composites.

a Schematic illustration of Ga/In-Bi composite conformally coated on a textile substrate, demonstrating X-ray attenuation capability. b Demonstration of the composite’s mechanical flexibility in a soft state, maintaining structural integrity under bending. c Photograph of a cotton glove uniformly coated with the Ga/In-Bi composite and subsequently encapsulated with a HPPU layer via dip-coating. d Cross-sectional SEM image of the coated glove, clearly showing the three-layer structure: HPPU encapsulation (top), Ga/In-Bi composite (middle), and textile substrate (bottom).

This approach provides a scalable and reusable platform for the development of soft and non-toxic wearable radiation-shielding garments. By integrating material flexibility, high attenuation efficiency, and encapsulation durability, the proposed system enables the fabrication of wearable shielding devices, such as gloves, specifically tailored for use in low-dose diagnostic radiation environments.

Results

Effect of bismuth content on the phase behavior and mechanical characteristics of Ga-In-Bi composites

The phase behavior of Ga/In-Bi composites is highly dependent on the relative concentrations of Ga, In, and Bi, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. The x-axis indicates the weight percentage (wt%) of Bi in the composite, while the left and right y-axes represent the corresponding Ga and In wt% in the liquid metal (LM) phase, where LM wt% = 1–Bi wt%.

a Phase map of Ga/In-Bi composites as a function of Ga, In, and Bi concentrations, illustrating the emergence of liquid, soft, rigid, and granular states. b Liquid composite. c Granular phase observed at high Bi content. d Soft composite exhibiting mechanical flexibility, including twist and bend behavior when coated on PDMS. e Rigid composite showing brittle fracture upon bending.

Eutectic Ga-In (EGaIn, 75.5 wt% Ga and 24.5 wt% In) was initially used as a baseline liquid alloy to prepare the Ga/In-Bi composites. As shown in Fig. 2b–e, four distinct phase states were identified with increasing Bi content: liquid, soft, rigid, and granular. At low Bi concentrations (5 wt% or 15 wt%), the composite retained a liquid state similar to pristine EGaIn (Fig. 2b). The mixture exhibited a gradual increase in viscosity with increasing Bi concentration. When the Bi content reached approximately 25 wt%, the composite material transitioned into a soft state (Fig. 2d). This phase allows conformal coating onto flexible substrates such as PDMS and maintains mechanical flexibility during bending and twisting. Also the soft composite, despite its non-liquid nature, forms a conformal and mechanically adherent interface with the HPPU substrate under applied pressure, highlighting strong interfacial compatibility (Supplementary Fig. 2). Although direct tensile testing of the soft Ga/In–Bi composite was infeasible due to its semi-liquid nature, we quantitatively estimated its Young’s modulus (~561.2 kPa) using a rule-of-mixtures approach by comparing the mechanical responses of pristine and composite-coated HPPU films, thereby demonstrating its measurable yet minimal mechanical influence and suitability for integration into soft, flexible systems (Supplementary Fig. 3). At higher Bi concentrations of 35 wt% and 45 wt%, the composite initially retained as uniform soft state during material preparation while the temperature was maintained at 50 °C but solidified upon cooling to room temperature, exhibiting brittle characteristics. As shown in Fig. 2e, composites in this rigid-state form were prone to cracking upon bending, indicating a loss of mechanical flexibility. As demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 4, uniaxial tensile testing of the free-standing rigid Ga/In–Bi composite revealed a linear-elastic response followed by abrupt brittle failure, yielding a Young’s modulus of approximately 73.1 MPa, nearly two orders of magnitude higher than its soft counterpart, thereby confirming its substantially enhanced stiffness and structural rigidity. While the soft composite offers desirable flexibility, EGaIn can retain this state only up to a maximum of 25 wt% Bi. To enable higher Bi loading in the composite for enhanced radiation shielding, various Ga/In ratios were explored to identify compositions capable of maintaining the soft state at increased Bi concentrations.

As described in the “Methods” section, Ga and In were first combined to form a Ga-In liquid alloy with varying compositions. Stable liquid phases were obtained at Ga/In ratios of 70/30, 60/40, and 50/50 (wt%). In general, as the Ga content decreased and the In content increased, the viscosity of the resulting liquid increased. At 40 wt% Ga and 60 wt% In, In could no longer fully dissolve, resulting in undissolved solid In within the mixture (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Upon the addition of Bi microparticles, it was observed that the Bi content required to induce a soft state decreased as the In content increased. Specifically, 25 wt% Bi was needed to form a soft state in EGaIn, while only 15 wt% Bi was required for the 70/30 Ga/In alloy. In the 60/40 and 50/50 Ga/In liquid alloy compositions, as little as 5 wt% Bi was sufficient to achieve the soft state, and the composite retained this soft behavior even at a relatively high Bi content of 35 wt%. However, further increasing the Bi content in the 60/40 and 50/50 Ga/In liquid alloy compositions led to the formation of a dark gray colored granular composite (Fig. 2c), characterized by loss of cohesion and poor formability, indicating a transition away from the desirable soft state. An additional comparison of the composite phases with varying Bi content and Ga/In ratios is presented in Supplementary Fig. 6. This tunable behavior is likely governed by a tradeoff between Ga’s contribution to maintaining fluidity and In’s contribution to enhancing the bonding affinity with Bi. A balanced combination of fluidity and intermetallic interaction appears critical for maintaining soft morphology and behavior.

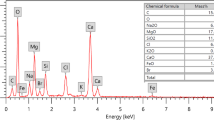

Morphological and compositional characterization of Ga/In-Bi composites

In (ZIn = 49) possesses a higher atomic number than Ga (ZGa=31), which contributes to better X-ray attenuation due to increased photoelectric absorption. Therefore, increasing the In content can potentially enhance the radiation shielding performance of the composite18. Based on this consideration, a 50/50 Ga/In ratio was selected to balance phase tunability with improved shielding efficacy. Figure 3 presents the morphological and compositional evolution of Ga/In-Bi composites with increasing Bi concentration, while maintaining a fixed 50/50 Ga/In weight ratio. The SEM micrographs in the first two columns, captured at low and high magnifications. The EDS elemental mapping images in the last three columns show the spatial distributions of Ga (red), In (green), and Bi (cyan). A clear spatial correlation between In and Bi is observed in the EDS maps, with both elements co-localized in discrete regions, indicating preferential interactions between Bi and In that lead to the formation of In/Bi intermetallic domains within the composite matrix. In contrast, Ga appears to be more evenly distributed throughout the matrix, forming a relatively continuous background phase. The SEM images reveal a progressive change in the distribution of In/Bi-rich particles as the Bi content increases. In Fig. 3a (5 wt% Bi) and Fig. 3b (15 wt% Bi), isolated and well-defined In/Bi-rich particles are sparsely distributed across a relatively smooth metallic matrix. As the Bi concentration increases to 25 wt% and 35 wt% (Fig. 3c, d), the surface becomes increasingly populated with densely packed In/Bi-rich domains. This trend indicates improved dispersion and integration of the secondary phase within the liquid alloy composite matrix (Supplementary Fig. 7).

SEM and EDS analyses of Ga/In-Bi composites at a fixed 50:50 Ga/In ratio with different Bi contents: a 5 wt%, b 15 wt%, c 25 wt%, and d 35 wt%. The first two columns show SEM images at low and high magnifications, revealing surface morphological changes with increasing Bi content. The last three columns present EDS elemental maps of Ga (red), In (green), and Bi (cyan), respectively, highlighting compositional distribution and homogeneity at each composition.

Radiation-shielding performance analysis of Ga/In-Bi composite

To evaluate the radiation-shielding performance of the Ga/In-Bi composites, Phy-X/PSD software was used to theoretically calculate key parameters, including the linear attenuation coefficient (μ), mass attenuation coefficient (μm), half-value layer (HVL), and effective atomic number (Zeff) across a range of photon energies. Among these, the linear attenuation coefficient \(\mu\) is a critical parameter that quantifies the fraction of radiation intensity attenuated per unit thickness of material. It is calculated using the Beer-Lambert law as shown in Eq. 1 below:

Where \({I}_{0}\) is the unattenuated photon intensity and \(I\) is the attenuated photon intensity, and \(x\) is the sample thickness in units of cm−1.

Mass attenuation coefficient \({\mu }_{m}\) accounts for the material’s density and reflects how effectively the material can absorb or scatter photons per unit mass as shown in Eq. 2, where \(\rho\) is the density of material19.

The \({HVL}\) directly quantifies shielding thickness, defined as the thickness required to reduce radiation intensity by 50%. It is given by:

The effective atomic number \({Z}_{{eff}}\) represents a weighted average atomic number that characterizes the composite’s response to X-ray interaction20. It can be estimated using the total atomic cross-section (\({\sigma }_{a}\)) and the electronic cross-section (\({\sigma }_{e}\)).

Figure 4a–d presents the calculated μ, μm, HVL, and Zeff for Ga/In-Bi composites with varying Ga/In ratios and the maximum Bi content that preserves soft behavior (ref to Fig. 2a). Higher values of μ, μm, and Zeff, along with lower HVL values, indicate improved radiation-shielding performance. Among all tested compositions, the composite containing 35 wt% Bi in the 50/50 Ga/In liquid alloy matrix exhibited the highest X-ray attenuation performance. The enhanced performance arises from two factors: a higher Bi content (up to 35 wt%) in the composite compared to the EGaIn-Bi composite, and a higher In content (up to 50 wt%) in the liquid alloy composition relative to other Ga/In ratios at the same Bi concentration. Notably, composites with 35 wt% Bi and varying Ga/In ratios exhibited similar attenuation performance, and all outperformed the EGaIn-25 wt% Bi composite. Because the photon attenuation cross-section (probability σt) increases with atomic number (Z), shielding ability follows Bi>>In>Ga. In the Ga/In liquid metal, Ga provides softness while In contributes most to attenuation. Therefore, a 50/50 Ga/In ratio offers the optimal balance of shielding performance and flexibility. Accordingly, this study focuses on the 50/50 Ga/In formulation and compares performance at different Bi weight ratios (Fig. 4e–i).

a–d Ga/In-Bi composites with varying Ga/In ratios and the maximum Bi concentration that retains a soft state. Calculated shielding parameters: a μ, b μm, c HVL, and d Zeff. e–i Ga/In-Bi composites with different Bi contents (5, 15, 25, and 35 wt%) at a fixed 50/50 Ga/In weight ratio. e Schematic illustration of the experimental X-ray attenuation setup used for measuring transmission through the composite. f Calculated results for Zeff. Comparison between calculated and experimentally measured g μ, h μm, and i HVL values. The inset plot highlights the experimentally measured results, including re-tested samples to assess long-term stability after two months. All plotted as a function of photon energy (1–1000 keV). j Comparison of recently reported Bi-based shielding materials with Ga/In-Bi composites.

The intended photon energy range spans 1–1000 keV and can be divided into two domains: from 1–100 keV, the photoelectric effect dominates and above 100 keV, Compton scattering prevails. In the photoelectric domain, when the incident photon energy exceeds an inner shell (K or L) electron’s binding energy, the photon transfers its energy to that electron to overcome its binding energy, and any excess becomes the kinetic energy of the ejected photoelectron21. Several phenomena are observed in that range. First, a higher Bi concentration shows a better attenuation, as evidenced by increased μ, μm, Zeff and decreased HVL in Fig. 4f–i. This improvement arises because the photoelectric absorption cross-section scales as Z4-5 and falls off as photon energy E−3.5. Consequently, shielding performance decreases rapidly as E increases. Second, distinct absorption peaks appear between 1 and 100 keV at the absorption edges. An absorption edge is the specific energy region in which X-rays excite inner shell electrons enough for them to escape the atom or move to a higher energy level. Absorption can change significantly at these edges22. Edges are named by shell, such as K for the most tightly bound, then L, M, and so on. Subscripts such as L1, L2, and L3 indicate specific electron transitions within that shell based on electron configuration22. For example, major peaks appear near 1.5, 15, and 100 keV, corresponding to the L1-absorption edge of Ga at 1.303 keV, the K-absorption edge of Ga at 10.368 keV, the L1-absorption edge of Bi at 16.376 keV, and the K-absorption edge of Bi at 90.538 keV23. Smaller peaks are also observed at 4 keV and 30 keV, corresponding to the L1 and K-absorption edges of In at 4.237 keV and 27.94 keV, respectively.

Above 100 keV, the HVL rises rapidly as Compton scattering becomes the dominant interaction24. In Compton scattering, photons transfer part of their energy to orbital electrons and are deflected25. The Compton scattering cross-section is proportional to Z and E−1. Still, higher-Z composites outperform lower-Z ones, but as E increases further, σ decreases, lowering photon electron interaction probability and gradually diminishing shielding effectiveness26,27. Consequently, a smooth performance declines from 100 keV onward.

To validate these calculations, an experiment was then conducted. The setup is shown in Fig. 4e, and the detailed procedures are described in the “Methods” section. Each composite sandwiched between Kapton tapes was mounted on a flat platform during measurement. X-rays from a Cu source were directed through the sample, and a filtered detector on the opposite side measured the transmitted intensity. The intensity through the two Kapton layers alone is denoted as\(\,{I}_{k}\), while the intensity through the composite layer with Kapton is denoted as \({I}_{s}\). With a known sample thickness\(\,{x}_{s}\), the linear attenuation coefficient of the sample \({\mu }_{s}\) was calculated using the following equation:

As the primary emission line of the Cu X-ray source in the Empyrean diffractometer is Kα, the photon energy applied in the experiment was fixed at 8.04 keV. The measured μ values for composites containing 5, 15, 25, and 35 wt% Bi (in a 50/50 Ga/In matrix) were 1007, 1098, 1205, and 1327 cm−1, respectively, as shown by the colored points in Fig. 4g. These agree closely with the theoretical values of 1018, 1113, 1215, and 1324 cm−1. To assess long-term stability, samples were re-tested after two months of room temperature storage. The measured μ values were 991, 1087, 1223,1345 cm−1 for the same composition (gray points in Fig. 4g). The near-identical results confirm that degradation and oxidation do not affect attenuation performance. Using Eqs. 2 and 3, the experimental values for μm and HVL were calculated and visualized in Fig. 4h, i. This strong agreement supports the validity of using Phy-X/PSD calculated data to predict the composite’s performance across different photon energy levels. Figure 4j compares the 35 wt% Bi in a 50/50 Ga/in metal matrix with Bi-based polymer matrix composites reported in recent studies12,13,28,29,30. This material outperforms others in μ, demonstrating superior X-ray attenuation.

Demonstration of wearable integration for radiation shielding

To demonstrate the feasibility of the Ga/In-Bi composite as a wearable radiation shielding material, a cotton glove was selected as a representative textile substrate. As shown in Fig. 5a, a standard cotton glove was used, and selective coating was achieved to produce a customized Penn State University logo pattern (Fig. 5b). The entire glove was fully coated with composite material, resulting in a conformal and flexible layer (Fig. 5c). To enhance adhesion and prevent delamination of the coated composite material from the glove during motion, the surface was encapsulated with a 20 w/v% HPPU solution via dip-coating, as illustrated in Fig. 5d(i–v). After solvent evaporation and drying, the fully encapsulated glove exhibited excellent mechanical integrity and flexibility during repeated freehand movements, as shown in Fig. 5e. The structural integrity of the encapsulated glove was further evaluated using optical microscopy and cross-sectional SEM imaging coupled with EDS analysis. As shown in Fig. 5f–i, the encapsulated glove exhibits a well-organized multilayered architecture, highlighting the structural and elemental integration of each component. The top-view optical image (Fig. 5f) displays the uniform surface morphology of the glove, with the transparent HPPU encapsulation layer conformally covering the Ga/In-Bi composite coating beneath. The cross-sectional images in Fig. 5g, h, confirmed by both optical and SEM analysis, reveal a distinct layered structure consisting of the HPPU encapsulation, the intermediate Ga/In-Bi composite, and the textile glove substrate with clear interfacial boundaries. Figure 5i presents cross-sectional SEM and corresponding EDS elemental mapping images, verifying the spatial distribution of Ga (red), In (green), and Bi (cyan), all of which are uniformly confined within the composite layer. The carbon signal (magenta) highlights the underlying glove textile and is also visible in the topmost HPPU encapsulation region, reflecting the carbon-rich nature of the HPPU layer. Together, these results demonstrate the robust integration of the composite with the textile substrate, along with excellent structural conformity and mechanical durability. In addition to textile-based platforms, the composite can also be coated onto a variety of substrate materials (Supplementary Fig. 8), highlighting its universal applicability. The HPPU-encapsulated soft Ga/In–Bi composite demonstrates excellent conformal wrapping on curved surfaces with bending radii as small as 0.75 mm, highlighting its surface adaptability and mechanical stability (Supplementary Fig. 9). The soft composite demonstrates exceptional flexibility, achieving a bending radius as small as approximately 240 μm nearly allowing it to fold onto itself (Supplementary Fig. 10). After 1000 repeated bending cycles, the multilayered structure retains uniform encapsulation and structural integrity, confirming its mechanical durability and low permeability, which are key attributes for long-term reliability in wearable applications (Supplementary Fig. 11). These features collectively support the potential of the Ga/In-Bi composite system as a versatile platform for flexible and wearable radiation shielding applications.

a Pristine textile glove. b Customized textile glove with PSU logo pattern. c Textile glove uniformly coated with the Ga/In-Bi composite over the entire surface, demonstrating flexibility post-coating. The inset SEM image shows the composite morphology. d Sequential steps of the HPPU dip-coating process for encapsulating the composite-coated glove. The process includes sequential steps of (i) initial dipping, (ii) partial immersion, (iii) full immersion in the HPPU solution, (iv) withdrawal, and (v) subsequent drying and solvent evaporation. e Photographs demonstrate the mechanical flexibility and structural integrity of the HPPU-encapsulated glove during various hand gestures, without observable delamination or composite detachment. f Top-view optical image of the glove surface, illustrating the HPPU encapsulation layer covering the underlying Ga/In-Bi composite coating. g Cross-sectional optical image and h Cross-sectional SEM image showing the distinct multilayer structure comprising the HPPU encapsulation, Ga/In-Bi composite, and textile substrate. i Cross-sectional SEM image (left) and corresponding EDS elemental mapping images showing the spatial distribution of Ga, In, Bi, and C elements in the HPPU-encapsulated composite-coated glove.

In this article, we successfully developed a new class of soft, high-performance radiation-shielding materials that combine mechanical flexibility with exceptional X-ray attenuation efficiency. By leveraging the phase tunability of gallium-indium liquid metal and bismuth, this work provides a scalable and practical solution for wearable protection in low-dose radiation environments. Future efforts will focus on further optimizing the composition to balance softness, mechanical durability, and shielding performance under a wider range of radiation energies and environmental conditions. Integration of this composite with other wearable systems, such as sensors, wireless electronics, or smart garments, could enable multifunctional protective gear with applications in medical diagnostics, aerospace, nuclear safety, and disaster response.

Methods

Preparation of Ga/In-Bi composites

Bi powder (Sigma-Aldrich), Ga, and In with a purity of 99.99% were purchased and used as received. As shown in the preparation process schematic in Supplementary Fig. 1, solid Ga metal was first melted by heating in a water bath at approximately 50 °C for 10 min. Once it became liquid, the Ga was transferred into a glass bottle. A calculated amount of In, based on the target composition, was then added to the bottle and heated until it was fully dissolved into the Ga. The Bi powder was ground in advance to reduce particle size and ensure uniform particle distribution. It was then weighed according to the target composition and added to the Ga/In mixture. The mixture was magnetically stirred overnight on a hot plate maintained at 50 °C and subsequently allowed to cool to room temperature. Figure 2a summarizes the targeted weight percentages of each component used in the experiment and the corresponding phase states of the Ga/In-Bi composites. The soft behavior was selected for composite material preparation due to its desirable balance between fluidity and structural integrity.

Scanning electron microscope and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy analysis

The surface morphology and elemental composition of the composite materials were characterized using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM; Sigma VP, Zeiss) equipped with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS) system (Oxford Instruments). SEM imaging was performed at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV at various magnifications. For elemental analysis, EDS measurements were conducted using an applied voltage of 20 kV.

Numerical results of X-ray attenuation

To evaluate the theoretical radiation shielding performance of the composite, theoretical calculations were performed using Phy-X/PSD, a user-friendly online photon shielding and dosimetry (PSD) software available at https://phy-x.net/PSD31. The radiation shielding data obtained from Phy-X/PSD have been demonstrated to have good agreement with well-established Monte Carlo-based simulations (e.g. Geant4) and other computational tools (e.g., XCOM)31,32,33,34,35. Key parameters such as μ, μm, HVL, and Zeff were calculated across different material compositions. These calculations provided predictive insights into the influence of varying Bi content on the attenuation properties of the Ga/In-Bi composites.

Experimental evaluation of X-ray attenuation

Experimental validation of the theoretical shielding properties was conducted using X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis in transmission mode, performed with a Malvern Panalytical Empyrean multipurpose diffractometer (referred to as “Empyrean” in this report) equipped with a copper (Cu) X-ray tube. Each composite sample was fabricated on a 50 μm Kapton film by applying pressure and scraping to form a thin and uniform layer, using fixed-height side blocks as a guide. The resulting composite layer, with a thickness of several tens of micrometers, was then sealed with another 50 μm Kapton film to ensure mechanical stability and uniform X-ray exposure. To precisely measure the thickness of the sample, an electronic indicator (Starrett) was used, and the average values were recorded for data analysis. The X-ray beam setup included a 1/8° divergence slit, a 0.3 mm primary mask, and a 0.1 mm secondary mask. For each experimental condition, measurements were repeated three times to ensure reliability, and the average values were used for data analysis.

Preparation of polyurethane solution for dip-coating

A 20 w/v% HPPU (HydroMed D3, AdvanSource Biomaterials) solution was prepared by dissolving the polymer in an ethanol solution (ethanol:DI water = 95:5 volume ratio) under magnetic stirring for three days, followed by homogenization using a syringe equipped with 10 µm pore-sized polypropylene membrane filters.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of the study are available within the paper and Supplementary Information. Further data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Ou, X. et al. Recent development in X-ray imaging technology: future and challenges. Research 2021, 2021/9892152 (2021).

Kawamura, K., Qi, F. & Kobayashi, J. Potential relationship between the biological effects of low-dose irradiation and mitochondrial ROS production. J. Radiat. Res. 59, ii91–ii97 (2018).

Shin, W.-G. et al. A Geant4-DNA evaluation of radiation-induced DNA damage on a human fibroblast. Cancers 13, 4940 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Flexible and wearable functional materials for ionizing radiation protection: a perspective review. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150583 (2024).

Dakup, P. P., Porter, K. I. & Gaddameedhi, S. The circadian clock protects against acute radiation-induced dermatitis. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 399, 115040 (2020).

Behroozian, T. et al. Predictive factors associated with radiation dermatitis in breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Res. Commun. 28, 100403 (2021).

Stam, W. & Pillay, M. Inspection of lead aprons: a practical rejection model. Health Phys. 95, S133–6 (2008).

McCaffrey, J. P., Shen, H., Downton, B. & Mainegra-Hing, E. Radiation attenuation by lead and nonlead materials used in radiation shielding garments. Med. Phys. 34, 530–537 (2007).

Flora, G., Gupta, D. & Tiwari, A. Toxicity of lead: a review with recent updates. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 5, 47–58 (2012).

Wani, A. L., Ara, A. & Usmani, J. A. Lead toxicity: a review. Interdiscip. Toxicol. 8, 55–64 (2015).

Burek, M. J. et al. Grain boundary effects on the mechanical properties of bismuth nanostructures. Acta Mater. 59, 4709–4718 (2011).

Jagdale, P. et al. Determination of the X-ray attenuation coefficient of bismuth oxychloride nanoplates in polydimethylsiloxane. J. Mater. Sci. 55, 7095–7105 (2020).

Thumwong, A., Wimolmala, E., Markpin, T., Sombatsompop, N. & Saenboonruang, K. Enhanced X-ray shielding properties of NRL gloves with nano-Bi2O3 and their mechanical properties under aging conditions. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 186, 109530 (2021).

Noor Azman, N. Z., Wan Mohamed, W. F. I. & Ramli, R. M. Synthesis and characterization of electrospun n-ZnO/n-Bi2O3/epoxy-PVA nanofiber mat for low X-ray energy shielding application. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 195, 110102 (2022).

Dincer, O. et al. Lightweight, flexible, and antimicrobial X-ray shielding composites with liquid metal-derived bismuth-tin core-shell particles. Appl. Mater. Today 38, 102254 (2024).

Bakri, F., Gareso, P. L. & Tahir, D. Advancing radiation shielding: a review the role of Bismuth in X-ray protection. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 217, 111510 (2024).

Zhang, X., Liu, J. & Deng, Z. Bismuth-based liquid metals: advances, applications, and prospects. Mater. Horiz. 11, 1369–1394 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Radiation shielding properties of flexible liquid metal-GaIn alloy. Prog. Nucl. Energy 135, 103696 (2021).

Jackson, D. F. & Hawkes, D. J. X-ray attenuation coefficients of elements and mixtures. Phys. Rep. 70, 169–233 (1981).

Han, I. & Demir, L. Determination of mass attenuation coefficients, effective atomic and electron numbers for Cr, Fe and Ni alloys at different energies. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 267, 3–8 (2009).

Ziessman, H. A., O’Malley, J. P., & Thrall, J. H. in Nuclear Medicine (Fourth Edition) 24–36 (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014).

Wu, J. et al. Flexible stretchable low-energy X-ray (30–80 keV) radiation shielding material: Low-melting-point Ga1In1Sn7Bi1 alloy/thermoplastic polyurethane composite. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 192, 110603 (2023).

Loisel, G. P. X-Ray Absorption and Emission Energies of the Elements. https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1380185 (2016).

Hubbell, J. H. in Encyclopedia of Physical Science and Technology (Third Edition) (ed. Meyers, R. A.) 561–580 (Academic Press, New York, 2003).

White, S. C., & Pharoah, M. J. in Oral Radiology (Seventh Edition) 1–15 (Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014).

Medhat, M. E. & Wang, Y. Investigation on radiation shielding parameters of oxide dispersion strengthened steels used in high temperature nuclear reactor applications. Ann. Nucl. Energy 80, 365–370 (2015).

Mahmoud, K. A., Tashlykov, O. L., Sayyed, M. I. & Kavaz, E. The role of cadmium oxides in the enhancement of radiation shielding capacities for alkali borate glasses. Ceram. Int. 46, 23337–23346 (2020).

Sayyed, M. I. et al. X-ray shielding characteristics of P2O5–Nb2O5 glass doped with Bi2O3 by using EPICS2017 and Phy-X/PSD. Appl. Phys. A. 127, 243 (2021).

Kurtulus, R., Kavas, T., Akkurt, I. & Gunoglu, K. An experimental study and WinXCom calculations on X-ray photon characteristics of Bi2O3- and Sb2O3-added waste soda-lime-silica glass. Ceram. Int. 46, 21120–21127 (2020).

Sharma, A. et al. Photon-shielding performance of bismuth oxychloride-filled polyester concretes. Mater. Chem. Phys. 241, 122330 (2020).

Şakar E, Özpolat Ö. F, Alım B, Sayyed M. I., Kurudirek M. Phy-X / PSD: Development of a user-friendly online software for calculation of parameters relevant to radiation shielding and dosimetry. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 166, 108496 (2020).

Afaneh, F., Khattari, Z. Y. & Al-Buriahi, M. S. Monte Carlo simulations and phy-X/PSD study of radiation shielding and elastic effects of molybdenum and tungsten in phosphate glasses. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 19, 3788–3802 (2022).

Khattari, Z. Y. & Al-Buriahi, M. S. Monte Carlo simulations and Phy-X/PSD study of radiation shielding effectiveness and elastic properties of barium zinc aluminoborosilicate glasses. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 195, 110091 (2022).

Olukotun, S. F. et al. Investigation of gamma ray shielding capability of fabricated clay-polyethylene composites using EGS5, XCOM and Phy-X/PSD. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 177, 109079 (2020).

Khallouqi, A., Sekkat, H., El rhazouani, O. & Halimi, A. Phy-X/PSD and Gate/Geant4 analysis of gamma-ray shielding in novel tellurite-based glasses. Ceram. Int. 51, 8168–8177 (2025).

Acknowledgements

T.Z. acknowledges support from the Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics, the Materials Research Institute, and the Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at the Pennsylvania State University. T.Z. and C.-C.K. acknowledge the support of the National Taipei University of Technology-Penn State Collaborative Seed Grant Program (NTUT-PSU-113-01). The authors acknowledge Dr. Anthony Richardella for his assistance with the radiation transmission experiment. The authors acknowledge ChatGPT (OpenAI) for language polishing and assistance with the generation of Fig. 5d(v).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W. and H.L. contributed equally to this work. T.Z. conceived the project. T.Z., A.P., L.V. and C.-C.K. secured funding. X.W., H.L., S.A. and T.Z. developed the material. H.L. conducted the SEM and EDS experiments. X.W. and J.R. performed the computational radiation shielding calculations. X.W. and H.L. carried out radiation transmission experiments. X.W., H.L., and M.M. prepared the figures. X.W., H.L. and T.Z. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, X., Lee, H., Ahmed, S. et al. Non-toxic soft shielding materials for wearable X-ray protection. npj Soft Matter 1, 10 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44431-025-00008-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44431-025-00008-3