Abstract

Objective

Flipped classrooms have become popular in health-related education fields in recent years. The objective of this study was to test the flipped approach in ophthalmology and assess student perceptions comparing flipped and traditional classrooms for teaching an undergraduate ophthalmology curriculum.

Methods

This is a non-randomized mixed method study looking at flipped approach for undergraduate ophthalmology teaching in the UK. Two modules of the ophthalmology course were chosen for two blocks of medical students (n = 50) with a cross over design. The questionnaires included a quantitative and qualitative survey to assess student perceptions on various aspects of the flipped approach.

Results

The statistical and thematic analysis revealed a preference for flipped classroom with students preferring some topics (p = 0.028) in ophthalmology to be delivered as flipped sessions. Pre-learning was found to be structured (p < 0.001) and not a burden contrary to the general perception about flipped classroom. Poll Everywhere as an audience response system emerged as a good teaching-learning tool for case-based discussions (p < 0.001). It was noted that most students in this cohort preferred flipped classroom for their future teaching (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The concept of FC is a promising, effective, and flexible teaching approach which should be selected carefully for appropriate modules. A combination of flipped and traditional approach may be the best way forward to cater to the needs of the students when the expectations and demands are clearly on the rise with the evolving and emerging trends of novel and innovative changes across all specialties in medicine.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flipped classroom (FC) or blended learning is an emerging pedagogical approach where active learning is promoted by student-centred teaching. Students are exposed to learning through lectures, videos or reading material sent to them before the face to face session and classroom session is utilised for discussions to promote deeper learning and critical thinking [1]. The use of technology has been found to be useful in delivering the classroom session and the polling software used for this helps to increase engagement and interaction [2]. This represents a paradigm shift in education from teacher-centred to student-centred learning. Traditional classroom (TC) on the other hand can be didactic lecture-based where students passively absorb knowledge while listening to lectures.

Active student-centred learning in FC promotes interaction and engagement between learners and teachers in a manner that allows discussion, clinical reasoning, and critical thinking [3]. Importance of student participation by utilising effective learning strategies to stimulate knowledge acquisition is the key to active learning [4].

The FC concept in medical education has been critically appraised [5] and shows that FC creates higher level of learner engagement but it is still not fully clear if this translates to higher levels of knowledge retention and learner performance which would need further studies. FC approach demonstrates a promising platform for medical education using technology to overcome time constraints experienced in designing and delivering the medical curriculum.

FC has been tried by some medical schools in China and USA to deliver ophthalmology teaching to undergraduate medical students and some residents [6,7,8]. Variable uptake was noted in these studies and hence further studies are warranted to explore student perceptions on FC approach in ophthalmology. This paved way for our research looking at student perceptions and acceptability of FC for teaching the ophthalmology curriculum to 4th year medical students and comparison with TC in UK.

Materials and methods

This was a natural non-randomised mixed method study using a quantitative and qualitative approach with statistical analysis. Survey research using closed and open-ended questionnaires were used, this being the most practically feasible option for conducting the study due to the global Covid pandemic at the time.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from S-SPEC, the ethics board of Keele University by completing the required ethics application forms (S-SPEC 20-13) for the master’s project in medical education. Written approval was also obtained from the MBChB research advisory committee in Birmingham. Informed consent was obtained from all students involved in the study. The feedback questionnaires were fully anonymised and no individually identifiable data was collected at any stage.

The 4th year ophthalmology curriculum in Birmingham medical school in the UK is currently delivered as lectures and clinical skills sessions. The students get to attend specialised ophthalmology clinics and eye theatres to observe cataract surgery. The students also have continuous access to online resources and specialty specific teaching material updated on the online e-portal named Canvas. This study recruited a cohort of 50 students (4th year) allocated to the University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Trust (two hospital sites) in one academic year between June 2020 and April 2021. They rotated through specialty medicine as two blocks. Block 1 (n = 25) for 18 weeks and block 2 (n = 25) for the next 18 weeks and within this time undergo two weeks of ophthalmology, during which the intervention was applied.

Two of the subject modules: Loss of vision (LOV) and Cataract (CAT) were selected for this project to convert to the flipped model based on subject, content and availability of online resources which would stimulate interest and self-paced learning for the students. These topics were preferred as the content here is more concrete and less abstract which makes it better suited for a flipped approach based on a study that looked at FC in an ophthalmology course [8]. The LOV module was delivered as an FC session and the CAT module as TC for block 1 students (n = 25) and vice versa for block 2 students (n = 25).

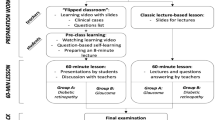

The TC session was delivered as a didactic lecture with no prior material provided beforehand. In the FC session, the students were asked to watch the online recorded lecture video and the available online resources for the topic on Canvas before the classroom session. The video presentation link was made available on Canvas and students were sent three email reminders to complete the online learning before they attend the scheduled FC session. The class time of two hours was used for discussion, and this was delivered as case-based discussion (CBD) covering the key learning objectives. Single best answer type multiple choice questions were used for delivering the CBD and the interactive polling software, Poll Everywhere audience response system was used to capture student responses with web-based interaction at the beginning and at the end of the session as a quiz. The students were divided into groups of five randomly for the final poll to promote teamwork and group discussions on the topic. There were 22 questions for the LOV module and 7 questions for CAT learning requisite as per the study. The didactic lecture is the same as the video lecture made available on Canvas for the same module of FC (see Fig. 1 for schedule).

The FC and TC modules were delivered by the same facilitator and feedback questionnaires collected for each of these modules in both groups.

The survey questions in the second questionnaire were predominantly open-ended questions to enable a qualitative analysis of the students’ perceptions and expectations. Students were asked to compare the two methods and comment on the pros and cons in this questionnaire.

Eligible students absent for the FC modules due to various unavoidable reasons or any student attending the FC without reviewing the online lecture were excluded based on the questionnaire response. One incomplete feedback questionnaire with significant information missing (i.e. three or more questions unanswered) was excluded.

All the statistical analysis were performed using the SPSS 27.0 version (Chicago, USA). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The open-ended questions were analysed using thematic coding and content analysis using the six-step standardised technique [9].

Results

Fifty students participated in this study (100% completion rate) with a slight female preponderance (58%) and the mean age was 22.4 years. The graduate entry students formed a small cohort in this group and was found to be only 14% of the total students. All students reviewed the pre-learning online lecture at least once with 25% of them reviewing the contents more than once before the teaching session. 59.2% students reviewed the additional online resources in the FC cohort and 54% in the TC cohort (mainly using the Canvas online). This suggests that more than half of the students admit to routinely accessing some online resources before they attend a TC lecture. 90% of the FC group and 56% of the TC group spent 30 min or more for pre-learning. It was noted that 30–60 min was a reasonable time that students can allocate for pre-learning using concise lectures.

Students in the FC cohort did not consider pre-learning to be a burden or take up too much time (p = 0.348). The student satisfaction was not found to be more for either sessions, be it FC or TC (p = 0.267). All students found that the pre-learning material was structured (p < 0.001) and classroom sessions with Poll Everywhere and CBD helpful (p < 0.001). The student perception on projected higher order gains were positive as well for FC which showed that the module improves motivation for independent learning to acquire knowledge (p < 0.001) and improves critical thinking and analysis of CBD (p < 0.001). The likeability was better for FC (p = 0.005) while satisfaction was not significantly more (P = 0.267). FC teaching methods were recommended for all ophthalmology modules by students (p < 0.001). See Table 1 for results.

Considering that all students who participated in this project had exposure to both FC and TC sessions with the cross-over design where the modules were swapped for the 2 groups of students over the academic year, [Group 1 (n = 25) FC-LOV and TC-CAT, Group 2 (n = 25) FC-CAT and TC-LOV] a comparison study of flipped versus traditional could also be undertaken for both the modules separately. The student satisfaction responses (statistical significance) with regards to burden of workload and time pressure, pre-learning, Poll Everywhere, effort, motivation, critical thinking, satisfaction and recommendation were similar for CAT and LOV modules when FC was compared to TC. A significant difference was noted for the likeability for LOV module as a FC (p = 0.028) session versus CAT module as FC (p = 0.074) as noted in Table 2. This suggests that some topics in ophthalmology are preferred more by students for the FC sessions as a method of teaching over TC.

Poll Everywhere as a method of teaching was widely appreciated and liked by students as noted on the free-text feedback in the questionnaires (‘liked the variety of approaches and using poll everywhere for case-based discussion, ‘case-based learning mirrors clinical environment and engaging/ interactive’). The engagement and participation were notable and conspicuous with a 92% response rate for the quiz and polls. Quizzes with anonymous polling and the CBD were liked by students and helped with engagement and learning as picked up from free text comments. (‘liked anonymous polling’, ‘polling question at start engages and prepares for case discussion’, ‘more efficient and streamlined and quiz stimulated thinking’, ‘quiz with poll helpful to consolidate pre-learning’, ‘starting the lessons with the polls was a good idea’, ‘polling was a different approach and stimulating’).

It was noted that FC-LOV seems to be the most preferred module over and above the other three sessions in the survey and the future choice for teaching sessions by students showed a preference for FC as captured in Fig. 2.

The FC sessions met expectations of medical students in 95.5% versus 88.6% for the TC group. Interestingly students felt that the TC lectures were good enough, specifically regarding not needing post session review of online resources to consolidate learning. Only 43% ended up reviewing the CBD learning questions given to take home and online resources post session. The main themes identified for FC preference following the coding process (Table 3) were engagement and participation (40%), retention of knowledge (25.3%), CBD for examination preparation (16%), Poll Everywhere as a new teaching tool (16%) and active learning (2.7%). The main themes identified for TC preference (Table 3) by students were passive learning (30.4%), better understanding of complex topics (26.1%), less work for students (26.1%) and easier multitasking (17.4%). TC sessions preferred by the smaller cohort (17.8%) felt that it is not feasible or realistic to do all lectures as FC due to the breadth and depth of the ever-increasing exponential rise in curriculum requirements. On the other hand, the majority (71.1%) of students who preferred FC sessions for future teaching have felt that the FC per se is more stimulating, interactive, and engaging with potential for application to all lectures as they did not find it time consuming.

Discussion

FC promotes higher order levels of learning in the classroom while this is achieved after the class in traditional lecture-based learning [10]. Meta-analysis has shown that FC (including pre-session quizzes) in medical education has grown rapidly since 2012 with the advantage of learning anywhere, anytime at one’s own pace and facilitating recall [11].

A systematic review of FC in medical education has concluded that there is still lack of solid evidence to prove effectiveness of FC over and above TC [12]. Available research from China suggests good FC uptake when applied to ophthalmology clerkship with appropriate content selection for flipping [8]. The FC approach has been noted to improve classroom interaction and can empower students to improve independent thinking and critical analysis of clinical scenarios [7]. Other studies have shown the effectiveness of integrated modular teaching (including FC and team-based learning), short pre-recorded videos and case-based discussions among ophthalmology trainees [13,14,15]. Some of these studies have also suggested that specific interest in a subject is not essential to view FC format positively and supports a wider application of FC format to other specialties that have time constraints to complete the curriculum. Certain topics were found to be better understood and liked by trainees when delivered by the TC approach as shown on post-test scores which is why a combination of FC and TC sessions are more favourable for teaching certain clinical skills in ophthalmology [16].

The current study results demonstrate that FC sessions are an effective method for delivering undergraduate teaching in ophthalmology. A more recent systematic review post Covid has concluded that students show satisfaction and are receptive to flipped interventions but concerns of work load and lack of time for preparation has been raised by students across many studies [17]. Our study showed that the majority of students spent about 30–60 min for pre-course work and found that the pre-learning resources were structured and helpful and did not take up too much time, similar to other studies [15]. It was also interesting to note that students voluntarily did some pre-learning and review of available resources before the TC even though they did not have to do it for this study which suggests that pre-learning may be acceptable to students for all types of classrooms if learning resources are stimulating, engaging and well structured. However, it should be interpreted with caution since all students were aware that they were in a study and whether this influenced their immediate behaviour is unknown.

Comparison of FC to traditional lecture in a previous study highlights the need for utilising suitable technology in FC to facilitate engagement and interaction [18]. The use of technology with audience responses helps to make sessions interactive and enables active learning. Poll Everywhere in our study was found to be effective as a polling tool for quizzes before and after the lesson in the classroom, as has previously been shown in other allied healthcare courses such as pharmacy [2]. Utilisation of the polling quiz at the beginning of the class helps to objectively assess the extent of pre-learning and subsequent knowledge gaps. The quiz at the end helps to consolidate learning and wrap up the session effectively so that the students also feel they have a closure to the doubts and queries that had emerged during the discussions around the topic. In line with this observation, other researchers have noted that the implementation of quizzes as part of flipped models not only helps to gauge student learning but also primes the learner through knowledge recall [19] and increase the motivation to review content before class by learners [11, 12]. However, more clarity is still needed on whether embedded quiz in pre-class video lectures will improve long term retention [20, 21] or better used for formative than summative assessments [20, 21]. Assessments for longer term knowledge retention was beyond the scope of our study.

CBD learning was found to be an effective classroom approach for FC in ophthalmology in our study. It has been shown that FC with CBD was found to be more effective than TBL for improving daily performance in trainees [15]. On the other hand when TBL was done via case-based presentation, it was shown to foster independent clinical reasoning at the same time providing a supportive and interactive environment while increasing the joy of learning [22]. Teamwork and group discussions were promoted in our post polling quiz. The thematic analysis of student perceptions regarding CBD in our study showed that students favoured this approach due to a variety of reasons. Firstly, it was found to be engaging and stimulating thereby improving engagement and interaction similar to the previous observation that case-based FC improves student participation and confidence [7, 15]. Secondly, it was perceived to be good for examination preparation and helps with end of year multiple choice questions and OSCE training. Thirdly, it was felt that CBD helps to mirror real life clinical scenarios in ophthalmology and helps to apply learning from a very practical perspective. The use of images of eye conditions in the CBD questions helps to improve learning and retention in specialties like ophthalmology where findings in the fundus are very important in the diagnosis and management of eye conditions with loss of vision as observed in this study. It has also been noted to help with consolidation of pre-learning and stimulation of thinking, comparable to responses by participants in other studies [7, 15].

The themes identified from student comments favouring FC suggested that promoting engagement and participation before and in the classroom was one of the key highlights of FC in this study, as shown in some systematic reviews [12]. We also noted that retention of knowledge was the next emerging theme in our analysis of student perceptions with the in-classroom quizzes noted to be a good stimulus for thinking initially and combining the learning in the end as observed in other studies [19]. One must bear in mind that these students have to undergo life-long learning throughout their career, based on novel learning methods on a background of the pre-existing and established learning experience [23].

The main themes picked by students preferring TC were related to need for less work and more time for multitasking when undergoing a time pressured and high workload demanding broad curriculum. In the process of avoiding pre-learning, students can concentrate on different specialties allocated during the same week; thereby reducing their workload. Interestingly a recent study [24] has shown that the converse is also true where FC teaching was noted to improve long-term learning effectiveness in physiology without affecting their performance in other subjects completed during the same semester of the undergraduate medical course. Passive learning was preferred by students for better understanding of complex topics in our study as demonstrated in the thematic analysis of free comments by students. It was also noted by some students that a global FC approach is not realistic for all teaching due to the depth and breadth of workload expected from any undergraduate medical curriculum. A more recent study comparing remote online FC to a mix of FC and in-person teaching sessions showed a clear preference for the latter mixed method of teaching [25].

Even though most of the students showed preference for FC in this study, it must be noted that we only looked at two modules in ophthalmology which were chosen carefully. Hence, we can only infer that FC is an effective approach but cannot demonstrate a definite superiority based on the results. Application of machine learning and personalised feedback loops can be considered in the future to refine FC techniques.

Study limitations

The project was undertaken during the Covid pandemic and there were initial delays in starting the study after the registration of the project with the ethics committee due to the restrictions in the hospital with social distancing in place. Fortunately, we were able to deliver the FC and TC sessions in large lecture theatres with social distancing. The intervention was undertaken during a very stressful time for the medical profession. The facilitator was the same for both the flipped and traditional modules raising the possibility of some unconscious bias. A potential limitation was the smaller cohort and lack of objective assessments which could have been undertaken by pre and post intervention assessment exams but was beyond the scope of this study due to the logistics of medical school rotations in 8 hospital sites and other practical limitations at the time. This study was primarily designed to look at student perceptions and assessment of learner satisfaction by a quantitative and qualitative analysis of feedback questionnaires only. Hence, we can only infer that FC is an effective approach based on the analysis undertaken but cannot test the long-term learning effectiveness of FC for ophthalmology teaching.

Conclusions

This study identified that FC is more interactive, engaging and stimulating. It was noted that one topic was liked more than the other to be delivered as FC sessions despite careful selection to ensure that more concrete and less abstract subjects were chosen based on previous studies. This is yet again another pointer towards the fact that FC sessions may not be suitable for all modules in ophthalmology or for that fact any specialty. Even though pre-learning was not found to be a burden in this study contrary to the general perception about FC, it would not be realistic to expect pre-learning for all course work required to be covered in a time pressured manner and within the requirements expected from a high workload undergraduate medical curriculum. This study does not test the longer-term effectiveness of FC and hence further studies are warranted.

The concept of FC is a promising, effective, and flexible teaching approach which should be selected carefully for appropriate modules in every specialty within medicine. A combination of flipped and traditional approach may be the best way forward to cater to the needs of the students. One should be mindful of the student’s expectation as well while trying to attain the most in a smart, measurable, achievable, realistic and time bound manner to prepare them both for knowledge tests as well as OSCE assessments when the expectations and demands are clearly on the rise with the evolving and emerging trends of novel and innovative changes across all specialties in medicine.

Summary

What was known before

-

Flipped classrooms have become popular in health-related education fields in recent years. Although flipped classrooms have been tried in some ophthalmology clerkships outside the UK mainly China and USA, there have been mixed responses regarding student perspectives on various aspects of the course. Work-load burden with pre-learning and time pressure with FC has been raised by participants in many studies.

-

FC has been shown to be an effective and promising approach to promote active learning. This approach is found to be more engaging, stimulating and promoting deeper learning.

-

FC has scope for expansion and offers an opportunity to standardise ophthalmology medical education.

What this study adds

-

This would be the first reported study in UK looking at FC in Ophthalmology.

-

This study showed that pre-learning was not a burden for students and showed 100% uptake suggesting that well-structured, short and stimulating learning resources with colour pictures and illustrations can make it more engaging.

-

FC is not suitable for all topics in ophthalmology and appropriate content selection is the key. A combination of FC and TC would be the best way forward to cater to the needs of the students.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Gillispie V. Using the flipped classroom to bridge the gap to generation Y. Ochsner J. 2016;16:32–6.

Gubbiyappa KS, Barua A, Das B, Vasudeva Murthy CR, Baloch HZ. Effectiveness of flipped classroom with Poll Everywhere as a teaching-learning method for pharmacy students. Indian J Pharm. 2016;48:S41–S6.

Torralba KD, Doo L. Active learning strategies to improve progression from knowledge to action. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2020;46:1–19.

Prince M. Does active learning work? A review of the research. J Eng Educ. 2004;93:223–31.

Kraut AS, Omron R, Caretta-Weyer H, Jordan J, Manthey D, Wolf SJ, et al. The flipped classroom: a critical appraisal. West J Emerg Med. 2019;20:527–36.

Cabrera MT, Yanovitch TL, Gandhi NG, Ding L, Enyedi LB. The flipped-classroom approach to teaching horizontal strabismus in ophthalmology residency: a pilot study. J Aapos 2019;23:200 e1–e6.

Ding C, Li S, Chen B. Effectiveness of flipped classroom combined with team-, case-, lecture- and evidence-based learning on ophthalmology teaching for eight-year program students. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:419.

Tang F, Chen C, Zhu Y, Zuo C, Zhong Y, Wang N, et al. Comparison between flipped classroom and lecture-based classroom in ophthalmology clerkship. Med Educ Online. 2017;22:1395679.

Braun V, Clark V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitat Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101.

Lin Y, Zhu Y, Chen C, Wang W, Chen T, Li T, et al. Facing the challenges in ophthalmology clerkship teaching: is flipped classroom the answer? PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174829.

Hew KF, Lo CK. Flipped classroom improves student learning in health professions education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18:38.

Chen F, Lui AM, Martinelli SM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of flipped classrooms in medical education. Med Educ. 2017;51:585–97.

Xin W, Zou Y, Ao Y, Cai Y, Huang Z, Li M, et al. Evaluation of integrated modular teaching in Chinese ophthalmology trainee courses. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:158.

Alabiad CR, Moore KJ, Green DP, Kofoed M, Mechaber AJ, Karp CL. The flipped classroom: an innovative approach to medical education in ophthalmology. J Acad Ophthalmol. 2020;12:e96–e103.

Diel RJ, Yom KH, Ramirez D, Alawa K, Cheng J, Dawoud S, et al. Flipped ophthalmology classroom augmented with case-based learning. Digit J Ophthalmol. 2021;27:1–5.

Lu RY, Yanovitch T, Enyedi L, Gandhi N, Gearinger M, de Alba Campomanes AG, et al. The flipped-classroom approach to teaching horizontal strabismus in ophthalmology residency: a multicentered randomized controlled study. J Aapos 2021;25:137 e1–e6.

Naing C, Whittaker MA, Aung HH, Chellappan DK, Riegelman A. The effects of flipped classrooms to improve learning outcomes in undergraduate health professional education: a systematic review. Campbell Syst Rev. 2023;19:e1339.

Pickering JD, Roberts DJH. Flipped classroom or an active lecture? Clin Anat. 2018;31:118–21.

Phillips J, Weisbauer F. The flipped classroom in medical education: A new standard in teaching. Trends Anaesth Crit Care. 2022;42:4–8.

Rice P, Beeson P, Blackmore W-J. Evaluating the impact of a quiz question within an educational video. Tech trends. 2019;63:522–32.

Jones EP, Wahlquist AE, Hortman M, Wisniewski CS. Motivating students to engage in preparation for flipped classrooms by using embedded quizzes in pre-class videos. Innov Pharm. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.24926/iip.v12i1.3353.

Horne A, Rosdahl J. Teaching clinical ophthalmology : medical student feedback on team casebased versus lecture format. J Surg Educ. 2017;74:329–32.

Harden RM. What is a spiral curriculum? Med Teach. 1999;21:141–3.

Ji M, Luo Z, Feng D, Xiang Y, Xu J. Short- and long-term influences of flipped classroom teaching in physiology course on medical students’ learning effectiveness. Front Public Health. 2022;10:835810.

Doyle AJ, Murphy CC, Boland F, Pawlikowska T, Ni Gabhann-Dromgoole J. Education in focus: significant improvements in student learning and satisfaction with ophthalmology teaching delivered using a blended learning approach. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0305755.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the 4th year medical students who kindly participated in the study by attending both the teaching sessions and took the time to complete the questionnaires after each session. Their free text comments were invaluable for the thematic analysis undertaken here.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ—conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript. SJ—statistical data analysis and review of manuscript. NC—review of statistics and data analysis. VF—study supervision and critical review of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical consideration

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from S-SPEC, the ethics board of Keele University by completing the required ethics application forms (S-SPEC 20-13) for the master’s project in medical education on 04/08/2020. Written approval was also obtained from the MBChB research advisory committee and institutional review board in Birmingham at the same time.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all students involved in the study. The feedback questionnaires were fully anonymised and no individually identifiable data was collected at any stage.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jacob, S., Jacob, S., Cope, N. et al. Flipped and traditional classrooms in ophthalmology: an evaluation of the impact of a crossover study. Eye Open 1, 2 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44440-025-00003-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44440-025-00003-7