Abstract

Background

Recent studies have assessed quality-of-life improvements associated with serum eye drops, but existing data lack insight into indication-specific patient satisfaction. This survey aims to identify which patients benefit the most from serum eye drops, determine the cohort with the highest satisfaction, and understand their treatment experience.

Subjects/Methods

We conducted a patient satisfaction survey incorporating a combination of validated PROMs along with additional questions regarding the use of SED and the quality of service. Patients with severe ocular surface disease (OSD) who received allogeneic serum eye drops at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, United Kingdom, from 2020 to 2023 were identified from NHSBT clinical requests. Responses were collected between October 2023 and February 2024. Demographic details were collected, and associations between indications and patient satisfaction were analysed.

Results

Thirty-three patients (21–86 years old) returned the survey questionnaire. The majority were female (55%) and Caucasian (91%). The most common indication was ocular graft versus host disease (GvHD) (21%). The data analysed resulted in three primary themes: ‘quality of life’, ‘patient contentment with treatment for specified indications’ and ‘usability of treatment and eye-dropper vial’. The mean pre-and post-treatment OSDI score was 61 and 48 (p = 0.035, 95% CI).

Conclusions

Our data support the use of SED in patients with chronic and debilitating OSD, in particular those with immune-related dry eye disease and persistent epithelial defects. Overall, patient responses were very positive. 55% of patients felt vials were too large and raised concerns around environmental issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of serum eye drops (SEDs) has been demonstrated to be effective for severe ocular surface disease (OSD) since it was first described by Fox and colleagues in the 1980s [1] SED consists of elements present in tear film, allowing for corneal epithelial cell regeneration and proliferation, in addition to its anti-inflammatory properties optimising wound healing and repair [2] In 2003, the NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) began providing SED for patients with OSD in the UK. The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency classifies SED as an unlicensed medicinal product. This means that all licensed products should be considered and prescribed prior to the use of SED due to it being a highly specialised and costly treatment. Guidelines have been published by the Royal College of Ophthalmologists for the use of SED in severe OSD [3]. This is followed by a clinical commissioning policy statement regarding the treatment criteria and when to stop SED treatment [4]. Autologous and allogeneic SEDs have comparable efficacy and tolerability, but allogeneic SEDs offer greater standardisation and uniformity. Especially since the COVID pandemic, the use of allogeneic SEDs has increased due to health service restrictions preventing the collection of autologous donations from patients. In the UK, the serum is diluted with 50% saline before being transferred to a sterile dropper, which is then frozen, with a shelf life of 12 months from the date of donation [5]. The SED batch is delivered to patients packed in dry ice and delivered directly to the patient’s residence by a same-day courier. Upon receipt, the patient transfers the SED to their domestic freezer. Prior to use, each frozen SED vial is allowed to thaw at room temperature. The patient then applies the SED as instructed by the referring clinician.

Both autologous and allogeneic SEDs have similar efficacy and tolerability for use in severe OSDs thus eliminating the logistical challenges and additional costs incurred in the use of allogeneic SED [6, 7] While the current published patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) demonstrate a significant reduction in mean Ocular Surface Disease Index (OSDI) score in both autologous and allogeneic SED, indicating improvements in quality of life associated with use of SED in patients with severe or chronic OSD, limited data are available on satisfaction specific to their indications [6] Usability of the SED dropper vial has not been explored. The aim of this survey is to explore treatment satisfaction, expectations, dropper-vial usability and tolerability, and to determine patient satisfaction with SED specified to the indications of use. This would allow for more targeted treatment criteria and redesign of the dropper-vial if required, to make treatment more cost-effective and patient-friendly.

Subjects and methods

Patients attending the adult corneal service of Manchester Royal Eye Hospital, United Kingdom (UK), with severe OSD who met the criteria for allogeneic SEDs and received treatment from the years 2020–2023 were identified from clinical requests submitted to the NHSBT programme (Bluteq web-based software system). Forty-three patients who were identified were contacted via telephone to gain their consent to complete a questionnaire, of which 38 (88.4%) were happy to participate. Patients were given the option of a postal or telephone satisfaction questionnaire according to their preference. Responses were collated between October 2023 and February 2024. A response rate of 86.8% (33 out of 38) was achieved. All questionnaires were numbered accordingly.

PROMs were collected using a combination of validated questionnaires including the 12-items Ocular Surface Disease Index© (OSDI) questionnaire (Allergan plc, Irvine, CA, USA) to assess the severity of symptoms and an adapted 10 items treatment satisfaction module of the Impact of Dry Eye on Everyday Life (IDEEL) questionnaire (Alcon Research LTD, France) to assess treatment tolerability and usability, 0 to 10 confidence scales for treatment satisfaction and visual analogue scales as a psychometric response scale related to overall views on SED use and service provision (Appendix 1).

In addition to satisfaction surveys, patient demographic details, including diagnosis and indications, previous treatment, duration of treatment before starting SEDs, duration since starting SEDs treatment, efficacy of treatment, and potential complications and adverse reactions associated with allogeneic SEDs were collated. Patient characteristics are described in Table 1. OSDI scores prior to starting treatment were also obtained for comparison. We utilised the mean and standard deviation to calculate the paired t-test for pre- and post-treatment OSDI scores, including p values with a 95% confidence interval. Specific indications documented were based on those of clinical requests submitted to the NHSBT programme.

Ethical considerations

This was deemed to be a service evaluation, and there was no requirement for ethical review, confirmed by both the Health Research Authority and the University of Manchester’s online ethical review tools. The project was registered within Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust’s audit department (Project reference number 11969).

Results

Of the 33 patients (21–86 years old) who returned the survey questionnaire, 12 patients were started on allogeneic SED within a year of presenting to the adult corneal service. This includes patients with aniridia associated non-healing defect (n = 2), chemical injury (n = 2), other non-immune-related dry eye with severe cicatrisation (n = 2), Sjögren’s-related dry eye (n = 1), ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) with severe microbial keratitis (n = 1), ocular graft versus host disease (GvHD) (n = 1), other exposure keratopathy (n = 1), corneal transplant-associated non-healing defect (n = 1) and other supportive (n = 1).

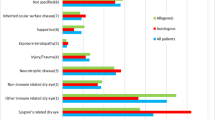

The mean year of starting treatment after presenting to the service is 4 years. The majority were female (55%) and Caucasian (91%). The most common indication was ocular GvHD (21%), followed by Sjögren’s-related dry eye (15%) and other non-immune-related dry eye (15%). Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) (Table 2) was stable in 29 (87.9%) patients and deteriorated in 4 (12.1%) patients. Reasons for deterioration of vision include progressive cicatrisation (n = 1), progressive peripheral ulcerative keratitis with corneal perforation (even prior to starting SED) in a patient with Sjogren’s syndrome (n = 1), progressive MMP (n = 1) and progressive limbal stem cell disorder from a severe chemical injury (n = 1). Six patients received treatment in only one eye due to a persistent epithelial defect from various indications that were refractory to other licensed treatments. All six had documented healing since starting SED, although three still require regular bandage lens exchanges in the clinic. We highlighted the essential areas concerning the application of allogeneic SED that we believed were pertinent to patients. The data we analysed resulted in three primary themes: ‘quality of life’, ‘patient contentment with treatment for specified indications’ and ‘usability of treatment and eye-dropper vial’.

Quality of life

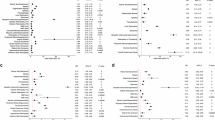

The mean pre-treatment OSDI score was 61, and the post-treatment score was 48 (p = 0.035, 95% CI), demonstrating an improvement in dry eye symptoms and their impact on vision-related function over the past week of the patient’s life.

Patient contentment with SED for their specified indications

Overall, 13 (39%) patients ‘strongly agree’ with how quickly SED worked. Of these 13 patients, five had ocular GvHD, three had ocular MMP, two had Sjögren’s-related dry eye, one had aniridia, one had non-immune-related dry eye, and one had ‘other’ immune-related dry eye. Two (6%) patients ‘strongly disagree’ with the statement, one of whom had non-immune-related dry eye and the other had exposure keratopathy secondary to thyroid eye disease.

Eight (24%) patients ‘strongly agree’ with how long the effects of SED lasted. These include one patient with a corneal transplant-associated epithelial defect, one with Sjögren’s-related dry eye, one with ocular MMP, one with non-immune-related dry eye, and two with ‘other’ immune-related dry eye.

Although five out of seven (71.4%) patients with ocular GvHD ‘strongly agree’ with how quickly the SED worked, seven out of seven (100%) responded that they ‘somewhat agree’ with how long the effects of SED lasted. This suggests that although it worked rather rapidly initially, the effect may start to become static with prolonged use.

Four patients (two with ocular MMP, one with ocular GvHD and one with ocular surface reconstruction) ‘strongly agree’ that SED completely eliminated their dry eye symptoms. Two patients with ocular MMP, one with aniridia and one with Sjögren’s-related dry eye ‘strongly agree’ that SED relieved most of their dry eye symptoms.

4/33 (12%) of patients reported side effects due to SED use, including residue in the eyes, blisters, soreness when used alone and aggravation of inflammation. One patient stopped using SED altogether due to the association of its use with ‘blisters all over their body’. This patient had a pre-treatment OSDI score of 72 and began SED for exposure keratopathy related to dry eye disease secondary to thyroid eye disease. She reported waking up with blisters all over her body 2 weeks after starting treatment, which cleared up a few days after discontinuing the treatment. Unfortunately, her experience with SED was unsatisfactory, and she reported no clinical improvement with its use, with an OSDI score of 96 after starting treatment. Correlating this data to their response on Q.25 (Appendix 1), the degree of side effects appears to have ‘greatly impacted’ (10/10) their overall satisfaction with SEDs.

We wanted to assess the correlation between post-treatment BCVA in 58 eyes that were treated, whether this influences overall satisfaction. Twenty-one out of 58 eyes had BCVA (LogMAR) worse than 0.3. Interestingly, the majority 13/21 (61.9%) of these patients with BCVA worse than 0.3 ‘were completely satisfied’ with overall treatment, followed by 5/21 (23.8%) that were ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 3/21(14.3%) ‘somewhat satisfied’. None of the patients with BCVA worse than 0.3 were ‘completely dissatisfied’.

Usability of treatment and eye-dropper vial

Three patients ‘strongly agree’ that they were bothered by how frequently they had to use SED. Among them, one was using it for supportive treatment of a non-healing epithelial defect, one for aniridia, and one for ‘other’ immune-related dry eye. All three patients used SED at least six times a day.

None of these patients were ‘strongly affected’ by the blurriness after using SED, nor were they embarrassed that they had to use SED. Only one patient (3%) was ‘somewhat affected’ by these.

Regarding overall views on SED, the instructions and service provision, 88% patients were ‘very confident’ with how to administer SED. Thirty-two (97%) patients reported that they have a good understanding of the reasons they were prescribed SED. Two patients require assistance in administering SED. Of the two patients who require assistance, one had Sjögren’s-related dry eye disease on a background of seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, and the other patient had ‘other’ immune-related dry eye disease on a background of rheumatoid arthritis.

We had mixed responses on the usability and practicality of the SED eye-dropper vial (Fig. 1). Eighteen (55%) felt that the size of the eye-dropper vial was larger than required, whereas two (6%) felt that this was insufficient. Interestingly, the two patients who felt that they were insufficient used SED over eight times a day on a daily basis, one was indicated for immune-related dry eye and another for Sjögren’s-related dry eye. Twenty-six (79%) patients reported that the number of SED vials given to them at a given time is ‘just ideal’. We further categorised the data of 32 patients (excluding one patient who stopped treatment). Seventeen patients who use SED ≤ seven times a day described the size of the vial as ‘just ideal’ or ‘more than required’. Only 2/12 (16.7%) patients who use SED between 8 and 10 times a day described the size as insufficient. Of the two patients, one had Sjögren’s-related dry eye on a background of rheumatoid arthritis, and another had ‘other’ immune-related dry eye with a background body mass index of 44, though none of them required assistance with SED application. This could indicate practical difficulties with drop instillation, rather than issues with the sizing of the eye-dropper vial itself (Fig. 2).

Ten (30%) patients were ‘completely satisfied’ that their presenting symptoms had improved with the use of SED. Of these, four had ocular GvHD, two had Sjögren’s-related dry eye, one had ocular MMP, one had immune-related dry eye, one supportive for non-healing defect and one had aniridia. Eleven (33%) patients reported being ‘completely satisfied’ with the positive impact on their quality of life with the use of SED.

Overall, 6/7 (85.7%) patients with ocular GvHD, 2/2 (100%) patients with aniridia, 2/4 (50%) patients with ocular MMP, 2/5 (40%) patients with Sjögren’s-related dry eye disease, and 1/1 (100%) indicated for other supportive treatment were ‘completely satisfied’ with the use of SED to treat their eye condition. 1/1 (100%) patient were ‘completely dissatisfied’ as they had blistering all over their body and felt that this has impacted her overall satisfaction for the use of SED.

We also received suggestions from patients regarding the ‘issues’ they encountered with SED, as presented in Table 3. Despite these concerns, we received notably positive feedback on the use of SED and the service provision.

‘Overall, I am very happy with the eye drops. They are a huge improvement on any previous product and have greatly improved my quality of life’.

‘It’s a fabulous service and I consider myself very fortunate to be part of the programme’.

‘Couldn’t manage without them’

‘The drops enable me to manage chronic irreversible condition. The service is outstanding in my opinion - always pleasant, helpful, and reliable when I contact them to order and in delivery. Dread to think how I would cope without this. The most recent vials are good ‘droppers’ but once opened the top is easily dislodged/lost when in transit/being frequently used as I have to do’.

‘There is improvement. I would very much like to keep using serum eye drops’.

Discussion

We aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of SED, the service, patient understanding, usability, and tolerability of the SED eye-dropper vial among UK recipients in a single tertiary centre. The OSDI questionnaire is an effective tool in measuring vision-related quality of life and the severity of OSD. Many studies have shown a reduction of OSDI scores following commencement of SED, whether autologous or allogeneic [6, 8,9,10,11]. However, it is important for clinicians to assess drop usability and tolerability to enhance compliance with this expensive, non-licensed treatment. We utilised the IDEEL questionnaire, a reliable and validated tool, to evaluate the treatment’s impact on patient outcomes and its effectiveness. It comprises three modules of 57 items: dry eye impact on daily life, dry eye treatment satisfaction, and dry eye symptom bother [12]. We only used the 10-item dry eye treatment satisfaction module to avoid duplication with the OSDI questionnaire. We also included questions regarding overall satisfaction with the use of SED and the quality of care provided. A free-text comment box was added to allow patients to contribute any additional comments they wished to share.

It appears that patients with immune-related dry eye disease, such as ocular GvHD, ocular MMP and Sjögren’s-related dry eye disease, were most satisfied with the use of SED, and that their presenting symptoms had improved with the use of SED.

There were challenges identified with the use of the SED eye-dropper vial. A significant proportion of patients (55%) reported that an excessive amount of serum was being discarded from the daily vials, except for 6% patients who felt that the amount was insufficient, as they depend on SED on a daily basis, using them more than eight times daily. Additionally, a patient-reported difficulties opening the vials, especially the ‘Mark 2 vials’, due to arthritis. An article published by Latham and colleagues on achieving ‘net-zero’ in the dry eye disease care pathway offered valuable insights into alternative packaging and dropper systems. However, it highlights the need for extensive rethinking and significant efforts to develop a system that is cost-effective, sustainable, and reduces infection risk, especially for patients with vulnerable ocular surfaces [13]. Perhaps different-sized eye-dropper vials can be considered depending on the frequency requirements of SED. Nonetheless, limited studies are available at present on the optimal dose and frequency of SED for varying conditions [14].

Although the NHS England commissioning policy statement suggests discontinuation of SED 3 months after the complete healing of a persistent epithelial defect [4], six patients with persistent epithelial defects associated with various underlying conditions, such as ocular GvHD or limbal stem cell failure due to chemical injury, continue to use SED even after their defects have healed. All these patients benefited from the continual use of SED to reduce the risks of recurrent epithelial defects and superimposed infections on the compromised ocular surface. Despite many patients praising the treatment as ‘miraculous’, we did not determine if they would feel comfortable stopping the treatment or if they fear the disease might return, necessitating more clinical visits. Our survey data is limited as it does not include questions about patients’ willingness to stop the treatment. This should be considered in future survey data collection.

Patients with non-immune-related dry eye disease experienced the least benefit, showing worse outcomes and greater dissatisfaction. This dissatisfaction was linked to patient-reported adverse events. Having said that, patients with non-immune-related dry eye disease may have symptoms out of proportion due to neuropathic corneal pain and, therefore, do not benefit as much from SED use. Perhaps patients with non-immune-related dry eye could undergo in vivo confocal microscopy to identify pathological changes in the corneal nerves before considering SED [15]. Having a targeted approach to the management of dry eye disease based on its underlying cause would avoid unnecessary use of this cost-intensive treatment.

Post-treatment BCVA does not influence patient satisfaction. In fact, the majority of patients with BCVA worse than 0.3 were ‘completely satisfied’ with the overall use of SED to treat their ocular condition. This suggests that the SED provided more symptomatic relief of their underlying condition for progressive, debilitating eye conditions. The majority of the patients with ocular GvHD and ocular MMP do have impaired vision, and are still ‘completely satisfied’ with the treatment. Self-reported symptoms do not always correlate with post-treatment improvements in clinical measures such as tear film break-up time, degree of ocular surface inflammation and osmolarity. This means that treatments may improve clinical ocular features without improving symptoms or vice versa.

Conclusion

Our subjective and effectiveness data support the use of SED in patients with chronic and debilitating OSD, in particular those with immune-related dry eye disease and persistent epithelial defects. Overall, patient responses were very positive, with comments referring to the service as ‘fabulous’ and ‘outstanding’. Over two-thirds of patients were satisfied with the use of SEDs to treat OSD. Over half reported improvement in quality of life, correlating with an improvement in the average OSDI score, highlighting the benefits of SEDs. A small minority of patients reported side effects. Most patients were very confident in their understanding and administration of SEDs, showing that information sharing with patients has been effective. Given that patients felt the vials were too large and raised concerns around environmental issues, reducing wastage via alternative vials could be considered.

Summary

What was known before

-

Both autologous and allogeneic SED improve the overall quality of life and symptoms of dry eye disease.

-

There appear to be beneficial effects in patients with persistent epithelial defects not responsive to other treatment modalities.

What this study adds

-

Patients with immune-related dry eye (in particular ocular GvHD) and patients with aniridia (with limbal stem cell dysfunction) seem to be the most satisfied with the treatment.

-

Patients’ subjective perspective on the use of SED.

-

A proposal for eye-dropper vial redesign, as many patients expressed concerns about product wastage and environmental impacts, feeling that the vials were too large.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Fox RI, Chan R, Michelson JB, Belmont JB, Michelson PE. Beneficial effect of artificial tears made with autologous serum in patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arthritis Rheum. 1984;27:459–61.

Thorel D, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Benaïm D, Daien V, Gabison E, Saunier V, et al. Ocular sequelae of epidermal necrolysis: French national audit of practices, literature review and proposed management. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2023;18:51.

Rauz S, Koay SY, Foot B, Kaye SB, Figueiredo F, Burdon MA, et al. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists guidelines on serum eye drops for the treatment of severe ocular surface disease: executive summary. Eye. 2018;32:44–8.

Clinical Priority Advisory Group. Clinical Commissioning Policy Statement Serum eye drops for the treatment of severe ocular surface disease (all ages) [200403P]. NHS England; [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Serum-eye-drops-for-the-treatment-of-severe-ocular-surface-disease-all-ages-1.pdf.

The Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Serum Eye Drops for the Treatment of Severe Ocular Surface Disease. The Royal College of Ophthalmologists; 2017 [cited 2024 Jun 4]. Available from: https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Serum-Eye-Drops-Guideline.pdf.

Lomas RJ, Chandrasekar A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Kaye S, Rauz S, Figueiredo FC. Patient-reported outcome measures for a large cohort of serum eye drops recipients in the UK. Eye. 2021;35:3425–32.

Van Der Meer PF, Verbakel SK, Honohan Á, Lorinser J, Thurlings RM, Jacobs JFM, et al. Allogeneic and autologous serum eye drops: a pilot double-blind randomized crossover trial. Acta Ophthalmol. 2021;99:837–42.

Mahelkova G, Jirsova K, Seidler Stangova P, Palos M, Vesela V, Fales I, et al. Using corneal confocal microscopy to track changes in the corneal layers of dry eye patients after autologous serum treatment. Clin Exp Optom. 2017;100:243–9.

Urzua CA, Vasquez DH, Huidobro A, Hernandez H, Alfaro J. Randomized double-blind clinical trial of autologous serum versus artificial tears in dry eye syndrome. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:684–8.

Celebi ARC, Ulusoy C, Mirza GE. The efficacy of autologous serum eye drops for severe dry eye syndrome: a randomized double-blind crossover study. Graefe’s Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014;252:619–26.

Hussain M, Shtein RM, Sugar A, Soong HK, Woodward MA, DeLoss K, et al. Long-term use of autologous serum 50% eye drops for the treatment of dry eye disease. Cornea. 2014;33:1245–51.

Okumura Y, Inomata T, Iwata N, Sung J, Fujimoto K, Fujio K, et al. A Review of Dry Eye Questionnaires: measuring patient-reported outcomes and health-related quality of life. Diagnostics. 2020;10:559.

Latham SG, Williams RL, Grover LM, Rauz S. Achieving net-zero in the dry eye disease care pathway. Eye. 2024;38:829–40.

Vermeulen C, Van Der Burg LLJ, Van Geloven N, Eggink CA, Cheng YYY, Nuijts RMMA, et al. Allogeneic serum eye drops: a randomized clinical trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of two drop sizes. Ophthalmol Ther. 2023;12:3347–59.

Watson SL, Le DTM. Corneal neuropathic pain: a review to inform clinical practice. Eye. 2024 [cited 2024 Jul 16]. Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41433-024-03060-x.

Acknowledgements

The adult corneal service at Manchester Royal Eye Hospital wishes to express heartfelt gratitude to the patients who provided their feedback. The authors would also like to extend their sincere thanks to Dr. Akila Chandrasekar, Consultant in Transfusion Medicine (NHSBT), for supplying the images of Mark 1 and Mark 2 vials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Yee Ling Wong was involved in the conception and the first draft of the manuscript. Minji Jennifer Kim and Fiona Mary Carley contributed to the final draft. All authors collaborated on drafting the survey questionnaire. Zona Ismail was responsible for obtaining patient consent for survey participation and compiling survey data under the supervision of other authors. Yee Ling Wong carried out data collection to include demographic details and specific indications, as well as associating data with patient satisfaction. Minji Jennifer Kim and Fiona Mary Carley were involved in revising, critically appraising and final approval of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wong, Y.L., Ismail, Z., Kim, M.J. et al. Use of allogeneic serum eye drops: Does indication influence patient satisfaction?—Identifying the most satisfied patient cohort and usability of eye-dropper vial. Eye Open 2, 5 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44440-026-00012-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44440-026-00012-0