Abstract

The Oxia Planum region of Mars was selected as the landing site of the upcoming ESA ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover because of the match with science requirements as well as its relatively flat topography. Previous works mapped isolated boulders in the area but did not find any signs of fresh mass wasting activity. Here, we report on 48 newly discovered rockfall locations inside and around the landing characterization area. The freshness of many rockfalls at these locations is evidenced by the presence of prominent deep tracks. They tend to occur in common geologic settings, including possible small secondary craters and rounded isolated mounds which are widespread in the region. We argue that impact cratering played an important role in preconditioning slopes for rockfalls and distributing loose material, but specific triggers are elusive. Our geospatial measurements of rockfalls in Oxia Planum also enable estimating geotechnical properties (bearing capacity) of surface materials for the first time. We show that the bearing capacity of soil, a quantity relevant to the rover’s ability to traverse the area, is sufficient to support its weight. The presence of rockfalls in Oxia Planum opens up new possibilities for sampling geologic units otherwise inaccessible to the rover.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As a part of the ExoMars program, the European Space Agency (ESA) will launch the Rosalind Franklin (RF) Rover in 2028 with the goal of investigating the shallow subsurface of Mars in search of past and present signs of life1,2. The region of Oxia Planum3,4 has been selected as the location of the future landing site because it satisfies both the scientific objectives5 and engineering constraints, including various rover safety-related criteria of the mission. Regionally, the geology of Oxia Planum is a low relief plain located at the transition between heavily cratered units of western Arabia Terra and the low elevation Chryse Planitia3,6,7,8,9,10. Locally, since the mid Hesperian the region has been dominated by erosional processes4,11,12 exposing clay-bearing units and the degraded remnants of ancient fluvial systems in windows through to the Noachian terrains considered to be high priority astrobiological targets for the mission4,13,14,15,16,17,18.

For safe rover operation, the presence of objects larger than 20 cm within 2–3 m from the rover is considered hazardous19. For that reason various areas of interest were extensively searched for signs of boulders which would affect the terrain’s trafficability for the rover. Manual searches were performed in the center of the previous (2020) ExoMars prime landing ellipse20 and five different regions along the updated (2022) ExoMars landing ellipse21 (note that the landing ellipses have been updated each time the mission was postponed, see Fig. S1). This yielded insights into which geological units tend to be densely populated with boulders mapped down to ~1.75 m. More recently, a deep-learning based classifier was used to identify surface textures with boulder fields defined as “dense accumulations of float-rocks closer together than a few meters”, over an area that is wider than the 3-sigma landing uncertainty ellipse for ExoMars22,23, which have been included in the high resolution geological map for the mission24. No studies, however, have examined the region for rockfalls that could pose a direct threat to the rover25, constitute an additional exploration opportunity, or signify an ongoing erosion process different to aeolian processing26.

A recent rockfall event (also known as a boulder fall) consists of a boulder scouring the surface while sliding, rolling or bouncing downslope, leaving a track behind it ranging from a linear channel to a line of individual divots (Fig. 1). High-resolution surface images of various Solar System objects have revealed the presence of such tracks, e.g., on the Moon27,28,29, Mars30,31, asteroids32, and even comets33. On Mars, the age of very fresh-looking tracks has been argued not to exceed a few thousand years34,35. Boulder fields, on the other hand, may be several orders of magnitude older36 and could represent generations of rockfalls whose tracks were since destroyed by erosion. Mars is also known to host active mass wasting of boulders (with and without tracks) elsewhere: fresh rockfalls in before-after images separated by a few years have been reported at high latitudes37, and in other regions38,39. Sometimes very fresh rockfalls leave another observable: an ejecta pattern, which has been reported to fade over 4–8 Earth years38,40.

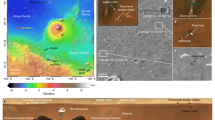

Yellow stripes in cluster views A–J highlight tracks, arrows point to associated clasts. The map view in the bottom right corner shows clusterlocations (squares) with respect to the ExoMars 2022 landing site characterization envelope (striped area) and existing HiRISE coverage (dark footprints). See Table S1 for image IDs.

The presence of extensive ejecta is also suggestive of how energetic the rockfall process can be. On Earth, meter-sized falling boulders can carry enough momentum to cause events analogic to explosions41. Our recent global study of rockfalls on Mars reveals that typical sizes of martian rockfalls can be as large as several meters in diameter31.

The discovery and characterization of rockfalls in the Oxia region would provide new information that reduces operational risk for the RF rover because it enables the first calculation of geotechnical properties of surface materials in the landing site region. In particular, modeling the bearing capacity42 can yield estimates of the maximal pressure that can be exerted on the surface of Oxia Planum without leading to a shear failure, which could cause the soil to trap a wheel of the rover. In the case of the Moon prior to the Surveyor and Apollo missions, bearing capacity was derived from geomorphometric measurements of rockfall tracks in surface images taken from orbit43. More recently, this approach has been applied to extended regions on the Moon44,45,46 and the asteroid Didymos32. Obtaining these estimates has not been possible in Oxia Planum previously due to the lack of sightings of fresh rockfalls and associated tracks.

In this work we use the semi-automatic search method recently published by our team31, followed by a detailed manual search, and provide a database of rockfalls found in and around the ExoMars RF landing site characterization area. Their geologic settings, possible drivers, and accessibility for the rover (i.e., their proximity to the ExoMars RF landing site characterization area) are investigated for the first time. This information is then used to provide insights into where more rockfalls could be found outside thoroughly searched images where either the semi-automatic approach fails to detect a rockfall, or the image coverage is currently incomplete. In addition, we estimate the soil bearing capacity in several areas across Oxia Planum, and thus contribute to the evaluation of hazards and trafficability for the RF rover.

Results

Rockfall tracks reflect the dynamics of the fall: differently spaced divots (low-velocity impact craters) suggest bouncing, smooth trenches - sliding, while zig-zag trajectories - rolling. Our sample of 258 rockfalls contains representatives of all of these categories (Figs. 1 and S2). We identified 48 source locations of rockfalls, i.e., separate landforms where either single (25 locations) or multiple (i.e., more than one) rockfalls (23 locations) share a common origin such as a bedrock unit (Table S1). We discuss them in greater detail below. At some sites the presence of either extensive boulder fields at the foot of the slope or half-buried clasts on the slope provides evidence for recurring mass wasting activity, and thus possibly more than one generation of past rockfalls (Fig. S3).

Rockfall characteristics

Approximately 80% of all rockfalls found in the area have boulder diameters smaller than 2.5 m and traverse less than 500 m before coming to a halt (Fig. 2). A few isolated rockfall events have diameters as large as 8 m or tracks more than 1 km long, with the latter more common inside large craters with long walls (Table S1). For a smaller sample of these rockfalls (see “Methods” section) we were able to utilize shadow lengths in order to calculate track depths close to the clasts (Fig. 2e). Those depths range from a fraction of a meter (a result bounded by the resolution of the camera) to 2 m for the largest clasts found in Oxia, with most typical trenches of the freshest rockfalls being less than 1.5 m deep.

These measurements can be further used to crudely estimate the order of magnitude of impact energy that could be carried by a boulder falling in Oxia Planum. We do this in two ways. (1) We assume that the total change in the mechanical energy of the system (factoring in the kinetic energy of a sliding rock and its potential energy, ignoring skidding, bouncing or rotation) is equal to the work done by the friction forces. We postulate that all variables except for velocity are known. The velocity of a clast at that point can be approximated with \(v=\sqrt{2g\Delta h(1-\mu \cot \alpha )}\), where g = 3.71 m/s2 is the gravitational acceleration on Mars; \(\Delta h=0-l\sin \alpha\) is the change in the vertical position between the source of the rockfall at rest and the end of the track of length l; α is the slope angle from horizontal; and μ is the friction coefficient (see also a schematic in Fig. S4). The values of these parameters can be taken from our analysis for this back-of-the-envelope calculation to be l = 100 m (a common value), α = 20° (the possible angle extracted from digital elevation models, Fig. S5b), \(\mu =\tan 3{0}^{\circ }\) (value of 30° being close to that found in the sediments of the Gale crater47). Under these conditions the velocity of a clast is ≈12 m/s. An idealized spherical rock of 2 m diameter with the density of 2300 kg/m3 (i.e., such as that found in sedimentary rocks in Gale crater48) would have the kinetic energy of 0.7 MJ, equivalent to 0.2 kg of TNT. (2) We assume that a boulder can be approximated as a solid sphere rolling down an incline. We ignore bouncing and skidding. The total potential energy is converted into a sum of the translational and rotational kinetic energy, thus \(v=\sqrt{\frac{10}{7}gh}\approx 39\) m/s for the same values of all parameters. The total kinetic energy is estimated to be 10 MJ, equivalent to 2.4 kg of TNT. These are crude approximations that likely constitute an upper limit on these energies. For a comparison, extremely energetic rockfalls on Earth can release more than 20 MJ of energy (most common rockfalls, ≤5 MJ)41. It thus follows from this analysis that some rockfalls in Oxia Planum can be energetic enough to leave ejecta patterns of disrupted soil like those observed in other locations on Mars40.

Because we lack repeated high-resolution surface images of the same locations prior to rockfall detections, it is not possible to determine if rockfalls occurred in the period of spacecraft observation. Several discoveries of rockfalls presented in this work have been made in images taken close to a decade ago, therefore we used them to test whether these areas are actively producing rockfalls on short timescales. Our repeat imaging campaign of seven different sites (Table S2) did not yield any new detections of tracks or clasts wider than 1 m, and thus the lower limit on the ages of these fresh rockfalls is at least a decade. If fresh rockfalls on Mars were of the order a thousand years old as postulated by several authors34,35, the change in track depth over this time would amount to only 0.1 mm under current conditions (max. erosion rate: 102 nm/yr49), a change which would not be resolved in orbital images. Although we cannot time-constrain these rockfalls, it can be expected that rockfalls with deep tracks comparable in size to clasts must be fresh. Such deep tracks will gradually become infilled over 10–70 Myr under current ambient aeolian conditions49, unless other mass wasting on steep slopes accelerates this process.

Locations

The 48 source locations identified in this work can be further grouped into clusters of co-located sources (i.e., all of the rockfalls in a cluster do not necessarily originate from the same source). The grouping of sources is related to the HiRISE image in which they were found (the image size is typically 5 km by 13 km). Grouping rockfalls in this way allows us to simplify the analysis and presentation of rockfall-bearing locations in the context of the regional geology and their distance from the rover. After grouping, clusters are separated by at least 10 km. We report on the discovery of 10 such clusters in the vicinity of the landing site (“nearby clusters”, labeled A–I), five of which are within the landing site characterization area, and 11 sites which are in the wider region (~80–300 km away, hereafter “distant clusters”, labeled 1–11; note that clusters labeled 7–10 in Fig. 3 are localized within McLaughlin impact crater ~90 km in diameter).

Nearby (A–I) and distant (1–11) rockfall clusters on top of the ExoMars 2022 geologic characterization envelope (the area with white stripes), shortening features62 and the geologic map9 with units denoting an epoch (A Amazonian, H Hesperian, N Noachian; e early, l late), and terrain type (i impact, t transition, h highland, o outflow, u undivided).

Figure 3 shows locations of these clusters with respect to the ExoMars landing site characterization envelope (white stripes). At the time of writing, ESA has not finalized the prospective envelopes for 2028 and recommended the use of the 2022 envelope for this comparison (see Acknowledgments). Although distant clusters are out of reach for the rover, which is projected to travel several kilometers during its nominal lifetime of 208 sols50, they can provide insights into terrains prone to rockfalls. This is especially important in light of the following: (1) the coverage with high-resolution images is sparse in the broader area of Oxia Planum; in fact, the new 2022 characterization envelope has not yet been fully imaged (see HiRISE footprints in Fig. 1 which cover about three quarters of its surface area) and as the mission has been further postponed due to the invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the new 2028 envelope will likely increase that imaging gap; (2) the automatic search which resulted in the identification of 48 individual rockfalls was conducted on the entirety of the HiRISE dataset but once we manually searched 14 out of 860 existing images (1.6%, including overlapping images) in the study region, we discovered 212 more rockfalls. Thus, we anticipate that future manual searches in the remainder of available images will yield many more rockfall detections. The prevalence of rockfalls in the distant sparsely-imaged region additionally makes it likely that even more rockfalls could still be found in Oxia Planum once it is fully imaged at high resolution.

A closer look at the clusters and associated source locations (Figs. 4 and S6) reveals that rockfalls are most commonly found on the inner and outer slopes of large primary craters (5 sources), in which case through their tracks can sometimes be traced to a particular geological unit (Table S1); secondary crater clusters (33 sources); mounds (3 sources); and other landforms with slopes such as scarps (2 sources). Additionally, it should be noted that all sources from cluster locations 6 and 7–10 belong to large-scale impact craters (40 and 90 km in diameter).

Drivers

The geologic context of these rockfalls can yield insights into their possible drivers, including preparatory and triggering factors. Recent studies identified that the region of Oxia Planum is located between topographically distinct highlands in the south and lowlands in the north3. Fluvial activity occurred during the early-to-mid Noachian15 (and could have played a role in forming fragments). There are vast clay-bearing sequences likely to have originated as sedimentary rocks or may have undergone in situ alteration depending on the context51. High resolution mapping shows that these units have more resistant units interbedded with them24 as seen exposed in the walls of impact craters walls52 and Pelso Chasma3 and are highly fractured4, possibly due to increasing pore-fluid pressures as a result of their burial53. They represent lithology conducive to boulder formation relative to the subjacent clay-bearing bedrock. Many dark resistant units are also seen capping mesas across the region54. These resistant units have surfaces dated to the Amazonian and boulder densities in that unit exceeding those in the Noachian unit by a factor of seven. This has been attributed to either different rates of production and preservation of boulders, or differences in exposure to impacts20. Finally, ~1% of Oxia Planum is covered by 396 mounds resembling buttes, mesas, or hills18 (see Fig. 5), hypothesized to be related to aqueous processes and interpreted as erosional remnants of sediments. Rounded and isolated buttes typically overlie and protect the clay-bearing unit of astrobiological significance4. In addition to material properties that would result in different responses to varied types of stresses or erosion, and different levels of exposure to impacts, solar radiation, too, could induce thermal stresses that can precondition slopes for fracturing35. In this section we analyze the geologic settings of discovered rockfalls and interpret them in the context of known rockfall-promoting processes.

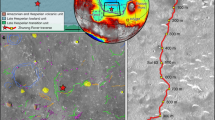

a Histograms of slope aspect (azimuthal axis, north is at 0°) at the individual rockfall sites (radial axis: counts). b The map showing rockfall clusters, densities of possible secondaries in Oxia Planum38 and widespread mounds18 with respect to the ExoMars 2022 geological characterization area (striped pattern).

Impact cratering

Rockfalls can be found in a variety of geologic units dated to have Noachian, Hesperian and Amazonian ages, and in highland, transition and undivided units (Fig. 3). As mentioned in the previous section, the steep slopes of possible primary and secondary craters are the most common source locations of discovered rockfalls, followed by mounds/buttes (Table S1). These two observations indicate that cratering may be a dominant factor in promoting new rockfalls in the region through both fragmenting the target and producing steep slopes.

Possible secondary craters recently mapped down to 50 m diameter in the wider Oxia region55 are 3.3 times more abundant in the area north of the center of the landing region than in the south (Fig. 5b). This greater abundance implies denser impact-generated fracture networks and potentially a higher chance of fresh rockfall formation in the north vs. south of the landing characterization area. In fact, the overlap between the landing characterization area (black area with stripes) and the number density map of possible secondary craters (Fig. 5b) reveals that the RF rover has the possibility to traverse heavily impact-fragmented areas. Since the majority of secondary craters have radii of 25–50 m (Fig. S7), we can use recent simulations of 50 m-diameter craters conducted by members of our team56 to better understand the scale of underlying fragmentation. The extent of fragmentation in relevant subsurface models for Oxia (i.e., containing sediments or breccia with top regolith layers), reaches as far as 2–4 crater radii away from the crater, vertically and horizontally (Fig. S8). To interpret this result in simple terms, a patch with 28 craters per km2 (Fig. 5b) could be entirely fragmented down to 100 m depth (this estimate assumes that craters are 50 m in diameter, target fragmentation reaches out to 4 crater radii, and that fragmentation zones between craters do not overlap).

Such a high density of possible secondary craters further points to a large amount of loose debris ejected from craters and widely redistributed across the region, either as a rain of fragments smaller and slower than those that created secondary craters, or from ejecta from secondary impacts. A good example of such loose clasts can be observed in the fresh ejecta of a well-preserved 300 m-diameter crater found 8 km away from the possible secondary crater field hosting rockfall cluster D (Fig. S9).

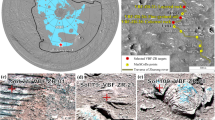

Fragmentation of buttes

Of the 396 mounds in Oxia Planum, 15 are known to exhibit layering and have loose boulders with no discernible tracks at their base18. The hypotheses put forward for the source of these boulders are that they are either erosional products of the outcrops or were transported from elsewhere in Oxia Planum. Evidence for the former includes the observation that the mound-forming unit has been fractured on a decameter scale, either via hydraulic deformation of deeper layers4,53 or contractional processes (dessication, thermal contraction) resulting in horizontal tensile stresses18,57. However, most mounds appear to have smooth textures on a meter scale and lack a cap rock.

The mounds hosting rockfalls in Oxia Colles (Fig. 6) and Ares Vallis (e.g., Fig. 4, cluster 1) are isolated and rounded, and they share common surface features such as widely scattered clasts and blocks (either half-buried or loose), as well as the presence of fields of craters several to tens of meters in diameter which vary in their degree of degradation. Numerous loose meter-scale boulders anchored high on slopes seem to be important for rockfall formation, as two rockfalls at two locations came from isolated blocks about 11 m in diameter. Of the rockfalls found on the mound in cluster 5, a few were inside a possible secondary crater on its top. Cluster 5 (Fig. S6) is particularly informative, as hundreds of loose boulders can be seen all over the surface of this butte, and they appear to feed a large accumulation of clasts at the bottom of this formation. Hence, it is plausible that boulder fields surrounding mounds are sourced from these outcrops. As all mounds in the region are argued to share a common origin18, it is very probable that more rockfalls could be found on other mounds and buttes, perhaps even in the region accessible to the rover. The abundance of buttes near the landing site, which besides craters are the primary sources of steep slopes capable of promoting rockfall formation in the region close to the ellipse, is illustrated in Fig. 5b. It thus follows that impact-related redistribution of clasts could be at least partly responsible for why boulder fields and rockfalls are found more frequently on mounds.

a 3D rendering of a HiRISE image (ESP_064604_1985_MRGB) on top of a digital terrain model with no vertical exaggeration (DTEEC_072039_2190_072250_2190_A01). b The location of a rockfall in the HiRISE image (north is up). c Rockfall on a meter-scale in the same image (north is up). Yellow lines highlight the rockfall track (the total track length is 75 m). Arrows point to the clast.

Other preparatory factors

Another finding that gives a clue to the origin of rockfalls is presented in Fig. 5a where we report our measurements of the slope aspect, i.e., which direction the slopes hosting rockfalls are facing. In primary craters (clusters G and 8), where the highest densities of rockfalls in any cluster were found, there is a preferential direction towards north-facing slopes. On buttes (clusters 1 and 3) the slope is facing north. In possible secondary craters the distribution of slope aspect also peaks to the north. This result is puzzling because the possible secondary craters in Oxia Planum appear to have formed in clusters with acute triangular shapes in planform with the apex pointing to the southwest55 (Fig. S10). This implies that projectile fragments could have impacted at shallow angles58 moving towards the north-east55. Highly oblique impacts produce asymmetric pressure fields in the shocked target subsurface59. Such impacts would preferentially break rocks in the downrange direction, towards the north-east. Hence, the asymmetries in target fragmentation towards the north-east due to oblique secondary impacts could explain a higher density of rockfalls on south-facing, not north-facing, walls inside craters. On the other hand, in an oblique impact uprange walls can be steeper than the downrange ones60, which promotes mass wasting. It is also worth noting that rockfalls on west-facing slopes are more difficult to spot because of the Sun-synchronous nature of the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s orbit31. Direct illumination of those slopes means that clasts or divots throw shorter shadows. This known observational bias does not, however, explain the higher abundance of rockfalls only on north-facing slopes that we observe in this area. Similarly, neither does the strong anisotropy of Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter sampling because it has a north-south vs. east-west nature61.

The abundance of recently mapped shortening structure ridges in the Oxia region62, interpreted as thrust-fault-related landforms, raises the question whether rockfalls could be of tectonic origin. However, only four clusters are co-located with the shortening features62 or troughs9 (Fig. 3). The proximity of a ridge does not always occur simultaneously with high density of rockfalls in a cluster. Moreover, these structural features of tectonic origin have typically north striking (east dipping) and south striking (west dipping) orientations, and thus do not explain the preferential orientation of our rockfalls. Due to these reasons, a tectonic origin for the rockfalls we observe is unlikely.

Recent works link insolation patterns with rock fracturing; for example, thermal stresses caused by diurnal temperature variations on the Moon were found to be sufficient to cause rock breakdown63. On Mars, solar-induced thermal stresses could potentially explain preferential orientations of cracks in boulders observed in-situ by Mars Exploration Rover64. Moreover, rockfall frequency appears to be correlated with the maximal diurnal average insolation over a full precession cycle35. However, since breakdown is also controlled by the characteristic boulder size as compared to the thermal skin depth65, and seasonal skin depth is greater than diurnal for a range of materials66, annual thermal stresses could be more important for rock fragmentation. Interestingly, the north-facing nature of rockfalls found in this study disagrees with the preferential slope aspect of rockfalls found far from Oxia Planum at similar latitudes which tend to be south-facing35. It is thus possible than another local process has been involved in preconditioning slopes. The topography with highlands in the south and lowlands in the north of the study region show a gradation in elevation of a few hundred meters over a horizontal distance of more than 200 km67. The vast valley networks, which were overlapped by non-degraded craters, converge to Oxia Planum into a catchment area4. Hence, thermal stresses and early fluvial erosion could have both preconditioned the impact-fractured subsurface for rockfall formation in Oxia Planum. These aspects require further investigation.

Recent triggers

The fall of prefractured material could have been accelerated by an instantaneous trigger such as seismic shaking. However, none of the recent marsquakes (InSight-recorded68 MQS v14 broadband and low frequency events) have their epicenters in Oxia Planum69. The closest impact site confirmed to have occurred in the period of spacecraft observation70 is also located too far away (~800 km away from the landing characterization area, more than 500 km away from the most distant cluster) to have influenced rockfall formation in the region with impact-induced shaking34. Although there is no proven link between any known recent triggers and fresh rockfalls in the region, we cannot rule out earlier triggers or seismicity promoted by changes in subsurface pore pressure71,72 that can result in stress propagation and fracturing far from marsquake hypocenters.

Trafficability

Fresh rockfalls with well-resolved shadows, for which we were able to calculate track depths (Fig. 2e), can be further used to estimate the bearing capacity of the martian regolith, q. This quantity is an important factor for this mission because it enables us to assess the region’s trafficability for the rover. Figure 7a summarizes the results of modeling this quantity using the Terzaghi equation42. We assume the soil material parameters to be similar to those obtained with in-situ measurements at Gale crater47, i.e., cohesion of 1.3 kPa, friction angle of 30°; and density of 1500 kg/m3. Rockfalls with estimated track depths used for this portion of the analysis are limited in quantity, and their numbers are insufficient to reliably study differences between terrains. However, as shown in Fig. 7a, we are able to use this technique to sample different geologic units discussed in previous sections. Resulting values of q range from 50 to 150 kPa.

a Bearing capacity (q) of martian soil in Oxia Planum as a function of depth and in various terrains. Size of the marker represents the average of the two boulder axes (width, height). Error bars mark measurement errors due to finite image resolution. b Sensitivity of the results to varying cohesion. c Sensitivity of the results to varying friction coefficient. Data in (b, c) is binned by track depth (shallow: <1 m, medium: ∈(1, 2) m, deep: >2 m), while error bars represent the range of possible values of q within these bins.

Strength parameters of the soil in Oxia Planum are not known; boulder size frequency distributions for diameters ≥1.75 m in selected units across Gale crater or Vastitatis Borealis (the Phoenix landing site) are different than those found in Oxia Planum, which may be indicative of different mechanical properties in addition to evidently different geomorphological settings20. Moreover, material properties can be expected to vary across different geological terrains even within Oxia Planum. For those reasons we performed a study of the dependency of model q on strength parameters, the results of which are presented in Fig. 7b (see also Fig. S11). The cohesion and the angle of internal friction are varied between the lowest and highest numbers uncovered in in-situ drills or thruster plume ground tests, with Gale-like strengths representing the lower end (i.e., 30°, 1.3 kPa) and strengths obtained by Phoenix in the Green Valley of Vastitas Borealisas the higher end (i.e., 38°, 7.5 kPa)47,73. The bearing capacity of soil increases with depth (panel a), which is why we bin the results in panel b by depth. This analysis shows that varying friction has a stronger effect on q than varying cohesion within these bounds. We use the results for the top 0.5–2 m of depth to infer the load that the RF rover can exert on the martian soil without causing shear failure. Resulting values range from 50 to 350 kPa. This is several times higher than the 11 kPa contact pressure (the load divided by the contact area) expected for each wheel of the RF rover74 and confirms that the rover could safely operate on a range of substrates present in the selected landing region.

Discussion

Our results show that rockfalls are abundant and may be an important part of the landscape evolution in Oxia Planum, yet the lack of activity at some rockfall sites over the last decade implies that a direct impact of a rockfall into a rover is extremely unlikely. Although we report a specific number of clusters and source locations of rockfalls in the study region, many more can be expected to be found in the future and some of them could coincide with the rover’s area of exploration. This is because (a) we manually searched only a small fraction of available high-resolution images within the landing site characterization envelope (i.e., only those images where the semi-automatic search identified rockfall bearing locations31, and those represent only a subset of all existing locations); (b) we did not include tracks that lacked obvious clasts at their ends; (c) falling clasts do not necessarily leave visible tracks if the terrain is not smooth or soft enough75, and so those cases have not been considered in this work. This study thus warrants follow-up investigations and more detailed manual searches for fresh rockfalls in all HiRISE images within the ExoMars landing site characterization area, an effort that may open possibilities for completely new investigations for the rover.

The RF rover can be expected to traverse several kilometers during its lifetime and has been designed to drive on slopes smaller than 10–26°, depending on the terrain type19. If more rockfalls are found in places that are within its reach, e.g., on shallow slopes and in areas suggested by our findings—on buttes or near heavily impact-fragmented ground—then the rover can be directed to those sites. This can have a range of benefits.

Increasing sample diversity

Clasts at the bottom of a rockfall can provide access to geologic units which might otherwise require a climb up a steep slope covered with loose material, likely impassable to a rover. Alternatively, if indeed some of these boulders were brought from other locations by fluvial processes20 or ejected from distant impact craters in the region before a fall, then visiting a rockfall would allow the rover to sample material from those regions. For example, one study suggests that the acute triangular shapes of possible secondary clusters in planform provides evidence for their common origin55: the 58 km-diameter Mojave crater, located a few hundred kilometers away at 7.5°N 33.0°W, and estimated to have formed 10 Myr ago76. Similar redistribution of material over large distances via impact cratering is not uncommon on the Moon77.

Investigating displaced subsurface material

The fact that rockfalls in Oxia Planum are capable of carrying megajoules of impact energy make them a very desirable target for exploration, particularly if fresh rockfalls ejected material upon impact, like the ones observed at other locations on Mars40. These products may probe the subsurface to depths that, as shown in this work, can exceed 1–2 m. Such fresh material has been partly shielded from radiation, and thus useful to probe for surviving organic materials25,78. Similarly, clasts of moderately recent rockfalls could be rotated upward, where poorly irradiated organics may be at surface access79.

Testing assumptions used to extract geotechnical properties

Our estimates should be treated as upper bounds on the actual bearing capacity because the wheels of the RF rover have a different shape and would exert a smaller load, resulting in shallower tracks. Lower bounds on bearing capacity must be obtained in dedicated in-situ experiments. The presence of a rover in the area of rockfall tracks would thus allow us to test and refine our modeled bearing capacity inferred from tracks observed by spacecraft. If RF visits more than one rockfall location, it could test our assumptions about the state of compaction, cohesion, friction angle, and boulder density, allowing for comparison of these values between sites. In principle, differences in these parameters could influence the track widths and depths, and ground-truth measurements of those unknowns would allow rockfall tracks to be utilized in studying near-surface regolith from spacecraft globally.

This work thus shows promise for using rockfalls in Oxia Planum in the future in order to increase the scientific return from the ExoMars 2028 Rosalind Franklin mission.

Methods

Rockfall database

Due to the meter-scale nature of rockfalls, the most suitable images for the purpose of searching for rockfalls come from the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) onboard Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (0.25 m/pixel)80. An object is considered a rockfall if a track representing its trajectory leads directly to a discernable clast. In order to generate the new rockfall database presented in this work we used a two-step approach: semi-automated search (step 1) and manual follow-up (step 2). In step 1, we made use of the output generated by the convolutional neural network recently published by our team31. That output contains a set of rockfall candidates produced by the algorithm with the confidence threshold (t) exceeding 0.6. This allowed us to perform a much more detailed search for rockfalls in the Oxia region than we were able to do previously for the entire planet, as that aforementioned paper followed a review of candidates only down to t > 0.8 due to the overwhelming amount of global output data. (We note that the algorithm searched the entire database of HiRISE images up until April 2023.) We then filtered the database of rockfall candidates based on the search area, which we selected to be a few degrees around the center of the ExoMars RF 2020/2022 landing characterization envelopes24 (Fig. S1), namely 13–23°N, 330–340°E. Following the same procedure as in the previous work, we conducted a human review of 3862 candidates with the aid of the Zooniverse platform (see Acknowledgments). Then, in step 2, we manually searched 14 HiRISE images, in which the algorithm had found at least one rockfall (see Table S1). The manual search increased the number of rockfalls from 48 to 258 compared with the semi-automated search; but the semi-automated step was necessary to efficiently target at least some rockfall-bearing locations.

Rockfall measurements

We mapped and measured rockfall tracks from the source to a clast, and the associated clasts, in the map-projected images using QGIS81. Clast widths and lengths came from polygonal bounding boxes that encompass each feature. The error on these measurements can be assumed to be ±2 pixels, i.e., 0.5–1 m (image sampling varies between 25–50 cm/pixel). Track lengths were obtained by summing up lengths of line segments making up each track and then correcting for the local slopes extracted from the Mars MGS MOLA - MEX HRSC Blended Slope82 (Fig. 5b). This is the highest-resolution slope map that is available at all rockfalls sites and that allows a broad comparison of rockfall characteristics. However, we note that for 26 rockfalls, which are situated in and around the landing characterization area, it is possible to obtain higher resolution slopes by using the Oxia Planum CTX DEM 20 m/pixel product3 (see Fig. S5a, c). Clast widths and lengths came from bounding boxes that encompass each polygon. The accuracy of these measurements can be assumed to be ±2 pixels, i.e., 0.5–1 m (image resolution varies between 25 and 50 cm/px). The sampling of the MOLA-HRSC slope map product (200 m/pixel) is comparable to track lengths. In order to assess the uncertainty on track lengths due to coarse resolution of the slope map, we measure the slope between the beginning and the end of the rockfall track from the one high-resolution digital elevation model produced for this work (DTEEC_072039_2190_072250_2190_A01, slope = 21°) and compare it with the one derived from MOLA-HRSC blend (slope = 12°). The error on the track measurement between the two amounts to 5%. Furthermore, we overcome scale challenges for slope aspect by measuring it in two ways. First, we used JMARS83 map sampling tool to extract its values from the MOLA 128 ppd Aspect product84 at the rockfall locations. Then, for rockfalls which we found on slopes that are below the map resolution of that product (e.g., in small secondary craters or round mounds), we manually estimated the slope aspect by measuring the angle between the direction of north in the HiRISE image and the line connecting the beginning and end of each rockfall track. Here we used the fact that rockfalls tend to follow the local topography downhill to visually identify the downhill direction. We estimate the error on these measurements to range from several to tens of degrees. However, we note that the bowl-shape nature of craters (or rounded nature of mounds) can also be used to qualitatively determine the aspect of a slope hosting a rockfall in terms of a direction (north, south, east, or west), which serves the purpose of this measurement. The final results are presented in this paper as histograms with an optimal number of bins (16) that primarily capture the directional trends (i.e., N–S, W–E).

Depth measurements

Not all rockfalls from our database are suitable for depth measurements. The selection criteria include freshness (no clear signs of prolonged erosion such as infill), size (the width of a track needs to be more than a few pixels long), shadow quality (of sufficient length to be resolved), as well as track geometry (e.g., zigzag tracks are excluded as those are formed by rolling of highly irregular boulders). We reviewed the shadows of all rockfalls in our database and identified 19 rockfalls fulfilling these criteria at 11 different locations (Fig. S12). After establishing the direction of illumination from the scene and image metadata, we measured shadow lengths close to the clast and along that direction in order to extract track depths, as per \(d=L/\tan (i)\), where L is the shadow length and i is the incidence angle of the image center85. This equation assumes a flat surface, which would hold in a scenario where a clast stops its movement at the bottom of a slope. Uncertainties on these depth measurements (see Fig. 7) are due to finite image resolution (i.e., ±2 pixels). If the exact inclination of the slope α close to the clast was known, a normalization factor N could be applied to the shadow length measurements where \(N=1+\tan (\alpha )/\tan (i)\) for positive and \(N=1-\tan (\alpha )/\tan (i)\) for negative slopes86. The additional uncertainty introduced to the depth estimates by this factor can be estimated using the full range of image incidence angles (i = 44°–60°), and slopes (α = 1°–21°), for the most common depth estimate of d = 1 m (Fig. 2). This results in a correction of ±0.01 m to 0.4 m (or 1–40%). Thus, the error due to image resolution dominates the uncertainty. Additional corrections could be made to take into account the emission angle and the difference between the subspacecraft and subsolar azimuths; however, these have been shown to have a fairly small effect on similar scale measurements in HiRISE data87.

Bearing capacity estimate

The geomorphometric measurements of rockfalls have been informing modeling of bearing capacity, i.e., the ability of soil to bear a load, since the Apollo era43,88. The most commonly used equation is the Terzaghi equation for spherical loads42, which assumes that soil failure occurs in general shear until enough volume of the target material is mobilized to resist it. General shear regime applies to high relative densities of foundation and soil, as is likely to be the case for loose unconsolidated regolith and dense solid clasts of rockfalls. We take our measurements of rockfall track depths d, together with the boulder widths and heights, and use this model of ultimate bearing capacity: q = 1.3cNc + dρgNq + 0.3ρgBNγ, where c is cohesion, Nc, Nq and Nγ are numerical constants that depend on the coefficient of internal friction, g is the gravitational acceleration, ρ is the density of regolith, and B is the diameter of circular footing which we adopt as the average of boulder width and length. The cohesion and coefficient of internal friction are the two free parameters in this model. We note that the Terzaghi equation assumes static equilibrium, which is generally violated anywhere on the track away from the clast, and requires that d < B. Following the methodology recently applied to lunar data44,45 and asteroids32, we performed our two measurements of shadow length per track as close as possible to the clast in order to conform to these assumptions.

Although other models exist, which consider the effects of inclined terrain and exact boulder shapes89, obtaining reliable measurements of those quantities is very challenging. Clasts are often too small to discern their exact shapes in two dimensions (see track depths in Fig. 2 which mostly fall into the 1–2 m range, i.e., 4–8 times the pixel scale), while computing precise slopes, especially in small secondary craters, would involve acquiring new stereo images in Oxia Planum that from our experience can take several months in this high-demand region (see below). Future work should consider these factors, which are beyond the scope of this work. We note that in areas with steep slopes a boulder mobilises less material underneath it to support it against sinkage when compared with flat surfaces, which in turn leads to deeper tracks, and lower bearing capacity.

Repeat imaging

We selected several approximately decade-old rockfall-bearing locations found in images taken approximately a decade ago for a follow-up imaging campaign with the HiRISE instrument. The campaign ran over the period of several months (from October 2023 to May 2024), and during this time we succeeded in obtaining seven new images (see Table S2). We used QGIS81 to georeference newly obtained images to the previous images by identifying points of reference and running a thin plate spline algorithm to warp the new images. We then compared image pairs by manually searching for sightings of new rockfalls both at the previously identified rockfall site and in the entirety of the overlap between the images. Due to the deterioration over time of the HiRISE hardware90, later images have increased noise and gaps, reducing the efficacy of these types of comparisons.

Data availability

All of the original spacecraft data used for this study are available on the Planetary Data System (https://pds.nasa.gov) and on the HiRISE team website https://www.uahirise.org/. A catalog with rockfall locations is provided on Zenodo91.

Change history

27 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44453-025-00010-z

References

Kereszturi, A., Bradak, B., Chatzitheodoridis, E. & Ujvari, G. Indicators and methods to understand past environments from ExoMars Rover Drills. Orig. Life Evol. Biosph. 46, 435–454 (2016).

Vago, J. et al. ESA ExoMars program: the next step in exploring Mars. Sol. Syst. Res. 49, 518–528 (2015).

Fawdon, P. et al. The geography of Oxia Planum. J. Maps 17, 621–637 (2021).

Quantin-Nataf, C. et al. Oxia planum: The landing site for the Exomars “Rosalind Franklin” rover mission: geological context and prelanding interpretation. Astrobiology 21, 345–366 (2021).

Changela, H. G. et al. Mars: new insights and unresolved questions. Int. J. Astrobiol. 20, 394–426 (2021).

Carter, J., Loizeau, D., Mangold, N., Poulet, F. & Bibring, J.-P. Widespread surface weathering on early Mars: a case for a warmer and wetter climate. Icarus 248, 373–382 (2015).

Carter, J. et al. A Mars orbital catalog of aqueous alteration signatures (MOCAAS). Icarus 389, 115164 (2023).

Ivanov, M. A., Slyuta, E. N., Grishakina, E. A. & Dmitrovskii, A. A. Geomorphological analysis of ExoMars candidate landing site Oxia Planum. Sol. Syst. Res. 54, 1–14 (2020).

Tanaka, K. L. et al. Geologic map of Mars: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Map 3292, scale 1:20,000,000, pamphlet 43 p (2014).

Steinmann, V. & Kereszturi, Á. Targeting shallow subsurface sampling for Mars at Oxia Planum using fluvial erosion–deposition modeling. Aerospace 11, 784 (2024).

Fawdon, P., Roberts, A. & Mirino, M. Impact crater degradation and the timing of resurfacing events in Oxia Planum, Europlanet Science Congress 2020, 21 September–9 Oct 2020, EPSC2020-55 https://doi.org/10.5194/epsc2020-55 (2020).

Favaro, E. A. et al. Periodic bedrock ridges at Oxia Planum and Chryse Planitia, Mars: evidence for widespread aeolian erosion of an ancient surface by regional paleowinds. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 626, 118522 (2024).

Brossier, J. et al. Constraining the spectral behavior of the clay-bearing outcrops in Oxia Planum. the landing site for the ExoMars “Rosalind Franklin” rover. Icarus 386, 115114 (2022).

Davis, J. M. et al. Ancient alluvial plains at Oxia Planum. Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 601, 117904 (2023).

Fawdon, P. et al. Rivers and lakes in western Arabia Terra: the fluvial catchment of the ExoMars 2022 rover landing site. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 127, e2021JE007045 (2022).

Gary-Bicas, C. E. & Rogers, A. D. Geologic and thermal characterization of Oxia Planum using Mars Odyssey THEMIS data. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 126, e2020JE006678 (2021).

Mandon, L. et al. Morphological and spectral diversity of the clay-bearing unit at the ExoMars landing site Oxia Planum. Astrobiology 21, 464–480 (2021).

McNeil, J. D., Fawdon, P., Balme, M. R., Coe, A. L. & Thomas, N. Mounds in oxia planum: the burial and exhumation of the ExoMars rover landing site. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 127, e2022JE007246 (2022).

European Space Agency. ExoMars 2018 Landing Site Selection User’s Manual, EXM-SCI-LSS-ESA/IKI-003 edn. Available at https://exploration.esa.int/s/wRd45j8 (2013).

Pajola, M. et al. Boulder abundances and size-frequency distributions on Oxia Planum, Mars: scientific implications for the 2020 ESA ExoMars rover. Icarus 296, 73–90 (2017).

Mastropietro, M., Pajola, M., Cremonese, G., Munaretto, G. & Lucchetti, A. Boulder analysis on the Oxia Planum ExoMars 2022 rover landing site: scientific and engineering perspectives. Sol. Syst. Res. 54, 504–519 (2020).

Barrett, A. M. et al. Noah-h, a deep-learning, terrain classification system for Mars: Results for the ExoMars rover candidate landing sites. Icarus 371, 114701 (2022).

Barrett, A. M. et al. Oxia planum, Mars, classified using the Noah-H deep-learning terrain classification system. J. Maps 19, 2112777 (2023).

Fawdon, P. et al. The high-resolution map of Oxia Planum, Mars; the landing site of the Exomars Rosalind Franklin rover mission. J. Maps 20, 2302361 (2024).

Sinha, R. K. et al. Boulder fall activity in the Jezero crater, Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL090362 (2020).

Kite, E. S. & Mayer, D. P. Mars sedimentary rock erosion rates constrained using crater counts, with applications to organic-matter preservation and to the global dust cycle. Icarus 286, 212–222 (2017).

Golier, M., Moore, H. & Martin, G. Lunar block tracks. A Preliminary Geologic Evaluation of Areas Photographed by Lunar Orbiter 5 Including an Apollo Landing Analysis of One of the Areas 143–154. https://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/nmc/publication/display.action?id=B01540-000A (1968).

Xiao, Z., Zeng, Z., Ding, N. & Molaro, J. Mass wasting features on the moon—how active is the lunar surface? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 376, 1–11 (2013).

Bickel, V. T., Aaron, J., Manconi, A., Loew, S. & Mall, U. Impacts drive lunar rockfalls over billions of years. Nat. Commun. 11, 2862 (2020).

Roberts, G. P., Matthews, B., Bristow, C., Guerrieri, L. & Vetterlein, J. Possible evidence of paleomarsquakes from fallen boulder populations, Cerberus Fossae, Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 117, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2011JE003816. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2011JE003816 (2012).

Bickel, V. T. et al. The first global catalog of rockfall locations on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110674 (2024).

Bigot, J. et al. The bearing capacity of asteroid (65803) Didymos estimated from boulder tracks. Nat. Commun. 15, 6204 (2024).

Fornasier, S. et al. Surface evolution of the Anhur region on comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from high-resolution OSIRIS images. Astron. Astrophys. - AA 630, A13 (2019).

Senthil Kumar, P. et al. Recent seismicity in Valles Marineris, Mars: Insights from young faults, landslides, boulder falls and possible mud volcanoes. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 505, 51–64 (2019).

Tesson, P.-A. et al. Evidence for thermal-stress-induced rockfalls on Mars impact crater slopes. Icarus 342, 113503 (2020).

Basilevsky, A., Head, J. & Horz, F. Survival times of meter-sized boulders on the surface of the moon. Planet. Space Sci. 89, 118–126 (2013).

Dundas, C. M., Mellon, M. T., Conway, S. J. & Gastineau, R. Active boulder movement at high martian latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5075–5082 (2019).

Grindrod, P. M., Davis, J. M., Conway, S. J. & de Haas, T. Active boulder falls in terra sirenum, Mars: constraints on timing and causes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094817 (2021).

Raack, J. et al. Present-day gully activity in Sisyphi Cavi, Mars—flow-like features and block movements. Icarus 350, 113899 (2020).

Vijayan, S. et al. Boulder fall ejecta: present day activity on Mars. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL096808 (2022).

De Blasio, F. V., Dattola, G. & Crosta, G. B. Extremely energetic rockfalls. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 123, 2392–2421 (2018).

Terzaghi, K. Bearing Capacity Ch. 8, 118–143. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9780470172766.ch8. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9780470172766.ch8 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 1943).

Hovland, H. J. & Mitchell, J. K. Boulder tracks and nature of lunar soil. Moon 6, 164–175 (1973).

Bickel, V. T. et al. Analysis of lunar boulder tracks: Implications for trafficability of pyroclastic deposits. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 124, 1296–1314 (2019).

Sargeant, H. M. et al. Using boulder tracks as a tool to understand the bearing capacity of permanently shadowed regions of the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 125, e2019JE006157 (2020).

Bickel, V. & Kring, D. Lunar south pole boulders and boulder tracks: Implications for crew and rover traverses. Icarus 348, 113850 (2020).

Arvidson, R. E. et al. Terrain physical properties derived from orbital data and the first 360 sols of Mars Science Laboratory Curiosity rover observations in Gale crater. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 119, 1322–1344 (2014).

Johnson, B., Milliken, R., Lewis, K. & Collins, G. Impact generated porosity in Gale crater and implications for the density of sedimentary rocks in lower aeolis mons. Icarus 366, 114539 (2021).

Golombek, M. P. et al. Erosion rates at the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites and long-term climate change on Mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 111, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2006JE002754. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2006JE002754 (2006).

Vago, J. L. et al. Habitability on Early Mars and the search for biosignatures with the ExoMars Rover. Astrobiology 17, 471–510 (2017).

McNeil, J. D. et al. Dichotomy retreat and aqueous alteration on Noachian Mars recorded in highland remnants. Nat. Geosci. 18, 124–132 (2025).

Srivastava, A. et al. Reconstruction of the subsurface stratigraphy of the ExoMars Oxia Planum landing site through investigations of exposed bedrock within crater walls. In Tenth International Conference on Mars, Vol. 3007 of LPI Contribution, 3233. https://elib.dlr.de/211442/ (2024).

Caswell, T. E. & Milliken, R. E. Evidence for hydraulic fracturing at Gale crater, Mars: Implications for burial depth of the Yellowknife Bay formation. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 468, 72–84 (2017).

Harris, E., Davis, J. M., Grindrod, P. M., Fawdon, P. & Roberts, A. L. A low albedo, thin, resistant unit in Oxia Planum, Mars: evidence for an airfall deposit and late-stage groundwater activity at the ExoMars rover landing site. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 129, e2024JE008527 (2024). E2024JE008527 2024JE008527.

Grindrod, P. M. et al. Extensive Secondary Cratering in the ExoMars Landing Site at Oxia Planum. In 54th Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, Vol. 2806, LPI Contributions, 1113. https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2023LPICo2806.1113G (2023).

Sokolowska, A. J., Collins, G. S., Daubar, I. J. & Jutzi, M. The link between subsurface rheology and ejecta mobility: the case of small new impacts on mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 130, e2024JE008561 (2025).

Bowen, A. P. et al. A cassis and hirise map of the clay-bearing unit at the ExoMars 2022 landing site in Oxia Planum. Planet. Space Sci. 214, 105429 (2022).

Oberbeck, V. R. & Morrison, R. H. On the formation of the lunar herringbone pattern. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. Proc. 4, 107 (1973).

Pierazzo, E. & Melosh, H. J. Melt production in oblique impacts. Icarus 145, 252–261 (2000).

Gault, D. E. & Wedekind, J. A. Experimental studies of oblique impact. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. Proc. 3, 3843–3875 (1978).

Kreslavsky, M. A. & Head, J. W. North–south topographic slope asymmetry on Mars: evidence for insolation-related erosion at high obliquity. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2003GL017795. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2003GL017795 (2003).

Woodley, S. Z., Fawdon, P., Balme, M. R. & Rothery, D. A. Map of tectonic shortening structures in Chryse Planitia and Arabia Terra, Mars. J. Maps 19, 2251514 (2023).

Molaro, J. L., Byrne, S. & Langer, S. A. Grain-scale thermoelastic stresses and spatiotemporal temperature gradients on airless bodies, implications for rock breakdown. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 120, 255–277 (2015).

Eppes, M.-C., Willis, A., Molaro, J., Abernathy, S. & Zhou, B. Cracks in Martian boulders exhibit preferred orientations that point to solar-induced thermal stress. Nat. Commun. 6, 6712 (2015).

Molaro, J., Byrne, S. & Le, J.-L. Thermally induced stresses in boulders on airless body surfaces, and implications for rock breakdown. Icarus 294, 247–261 (2017).

Putzig, N. E. & Mellon, M. T. Apparent thermal inertia and the surface heterogeneity of Mars. Icarus 191, 68–94 (2007).

Molina, A. et al. Coogoon Valles, Western Arabia Terra: hydrological evolution of a complex martian channel system. Icarus 293, 27–44 (2017).

Lognonné, P. et al. SEIS: insight’s seismic experiment for internal structure of Mars. Space Sci. Rev. 215, https://hal.science/hal-02188213 (2019).

Clinton, J. F. et al. The Marsquake catalogue from insight, sols 0–478. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 310, 106595 (2021).

Daubar, I. J. et al. New craters on Mars: an updated catalog. J. Geophys. Res.: Planets 127, e2021JE007145 (2022).

Manga, M., Zhai, G. & Wang, C.-Y. Squeezing marsquakes out of groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6333–6340 (2019).

Knapmeyer, M. et al. Seasonal seismic activity on Mars. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 576, 117171 (2021).

Shaw, A. et al. Phoenix soil physical properties investigation. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 114. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2009JE003455. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2009JE003455 (2009).

Patel, N., Slade, R. & Clemmet, J. The ExoMars rover locomotion subsystem. J. Terramechanics 47, 227–242 (2010).

Thomas, M., McEwen, A. & Dundas, C. Present-day mass wasting in sulfate-rich sediments in the equatorial regions of Mars. Icarus 342, 113566 (2020). Current and Recent Landscape Evolution on Mars.

Lagain, A. et al. Model age derivation of large Martian impact craters, using automatic crater counting methods. Earth Space Sci. 8, e2020EA001598 (2021).

Černok, A. et al. Lunar samples record an impact 4.2 billion years ago that may have formed the Serenitatis Basin. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 120 (2021).

Cockell, C. et al. Habitability: a review. Astrobiology 16, 89–117 (2016).

Kereszturi, A. & Steinmann, V. Sampling weakly irradiated organics without deep drill: case study of recently fallen and rolled boulders at the Jezero Delta, Vol. 3007 of LPI Contributions, 3029 https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2024LPICo3007.3029K (2024).

McEwen, A. S. et al. Mars reconnaissance orbiter’s high resolution imaging science experiment (HiRISE). J. Geophys. Res. Planets 112 https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2005JE002605. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1029/2005JE002605 (2007).

QGIS Development Team. QGIS geographic information system. https://www.qgis.org (QGIS Association, 2024).

Fergason, R. L, Hare, T. M., & Laura, J. Hrsc and mola blended digital elevation model at 200m v2. astrogeology PDS annex. https://astrogeology.usgs.gov/search/map/mars_mgs_mola_mex_hrsc_blended_dem_global_200m (U.S. Geological Survey, 2018).

Christensen, P. R. et al. JMARS—A Planetary GIS. In AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, vol. 2009, IN22A–06 https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2009AGUFMIN22A..06C (2009).

Smith, D. E. et al. Mars orbiter laser altimeter: experiment summary after the first year of global mapping of mars. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 106, 23689–23722 (2001).

Chappelow, J. E. & Sharpton, V. L. An improved shadow measurement technique for constraining the morphometry of simple impact craters. Meteorit. Planet. Sci. 37, 479–486 (2002).

Özdemir, I. S. Estimating stem volume by tree crown area and tree shadow area extracted from pan-sharpened QuickBird imagery in open Crimean juniper forests. J. Remote Sens. 29, 5643–5655 (2008).

Daubar, I. J., Atwood-Stone, C., Byrne, S., McEwen, A. S. & Russell, P. S. The morphology of small fresh craters on Mars and the Moon. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 119, 2620–2639 (2014).

Moore, H. J., Hodges, C. A. & Scott, D. H. Multiringed basins—illustrated by Orientale and associated features. Lunar Planet. Sci. Conf. Proc. 1, 71–100 (1974).

Hansen, J. B., Brinch, J., bullet, H. & nan, S. A revised and extended formula for bearing capacity. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:127983665 (1970).

McEwen, A. et al. The high-resolution imaging science experiment (HiRISE) in the MRO extended science phases (2009–2023). Icarus 419, 115795 (2024).

Sokolowska, A. Dataset for “Fresh rockfalls near the landing site of Exomars Rosalind Franklin rover: drivers, trafficability, and implications”. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15058575 (2025).

Dickson, J. L., Ehlmann, B. L., Kerber, L. & Fassett, C. I. The global context camera (ctx) mosaic of Mars: a product of information-preserving image data processing. Earth Space Sci. 11, e2024EA003555 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This publication uses data generated via the Zooniverse.org platform by our research team members. A.J.S., I.J.D., A.B. and I.H. were funded by NASA MDAP grant # 80NSSC22K1086. S.J.C. is supported by the French Space Agency CNES for her HiRISE-related work. C. Dundas, K. Wagstaff, G. Doran, and K. Bergen contributed to the NASA MDAP funding acquisition. P.F. was funded on UK Space Agency grant ST/W002736/1 and through the European Space Agency ExoMars Science Knowledge Program. We also thank B. Gosse for producing the HiRISE DEM, as well as M. Kreslavsky and other reviewers for their helpful suggestions. Elliot Sefton-Nash (ESA) provided information on the status of ExoMars landing ellipses for 2028. The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.S. designed and directed the study, obtained new HiRISE images, analyzed and curated rockfall data, provided interpretations, supervised data collection, and wrote the manuscript with input from all co-authors. V.T.B. provided rockfall candidates and supported A.J.S.’s modeling of bearing capacity. A.B. and I.H. identified true positives among these candidates and mapped these and other rockfalls in orbital images. P.F. contributed with Oxia-specific geological interpretations of rockfall sites. P.G. provided data on clustering and possible secondary craters in Oxia Planum. S.J.C. trained A.J.S. in using Zooniverse platform and contributed to data interpretation. I.J.D. acquired funding, provided critical feedback, and supported obtaining new HiRISE data.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sokołowska, A.J., Daubar, I.J., Bonab, A. et al. Fresh rockfalls near the landing site of ExoMars Rosalind Franklin Rover: drivers, trafficability, and implications. npj Space Explor. 1, 5 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44453-025-00008-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44453-025-00008-7