Abstract

Lunar infrastructure construction requires innovative strategies to minimize energy consumption and human intervention. This study presents a computational design method for robotic construction of lunar masonry structures using in-situ, unprocessed stones. The method iteratively determines the optimal placement of stones through an optimization formulation that incorporates both geometric and physical constraints. To achieve computational efficiency, the stones and the target structure are encoded in 3D tensors, and their geometric features are evaluated using discrete convolution. Stability of stone placement is assessed both geometrically, as optimization constraints, and numerically, through the Non Smooth Contact Dynamics method (NSCD). The proposed computational design method is applied in the planning of arches, domes, and walls, showing versatility across building components while also identifying limitations on the geometry of spanning elements. The robotic construction experiment for building a wall composed of 138 stones achieves a placement success rate of 95%, validating the construction feasibility and energy efficiency of building lunar infrastructure using unprocessed stones.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Establishing a long-term human presence on the Moon necessitates the construction of a wide range of infrastructure1,2,3, such as living habitats4, blast shields5, and scientific outposts6. One of the main constraints for extraterrestrial construction is the high cost of transporting material from Earth6,7. As a result, considerable research has focused on the In-Situ Resource Utilization (ISRU) method, which aims to harness local lunar resources, such as regolith, ice, and solar energy, to produce essential construction material2,8,9,10.

Many ISRU approaches involve processing lunar regolith into usable construction materials. This includes producing concrete-like composites or modular bricks4,7 through sintering techniques11, or by mixing regolith with binders transported from Earth12. Additionally, metals can be extracted from lunar soil via electrolytic reduction processes for structural applications3. However, these methods can be highly energy-intensive due to the high-temperature requirement or the necessity to import material from Earth1.

Alternative approaches that construct with unprocessed material, such as assembling natural boulders5 or unprocessed regolith particles13, have gained increasing attention. In contrast to other assembly-based construction methods that require casting regolith into specific shapes7,14,15, the direct use of unprocessed material, especially stones, eliminates the need for thermal energy to form construction units. It also minimizes the use of binding material by deliberate planning of the stones, similar to traditional masonry techniques13. In this regard, Walther et al. investigated the feasibility of constructing a 50-meter-radius blast shield using boulders ranging from 0.5 to 1.5 meters in diameter in regions near the lunar south pole5. Their method employed autonomous robotic excavators to collect naturally occurring boulders from the lunar surface and to assemble them without binders using a geometric planning algorithm16. The study demonstrated that this approach required orders of magnitude less energy than methods involving cast regolith or microwave sintering. Similarly, Eckman et al. evaluated the energy consumption of constructing an 800 km-long runway using multi-scale granular stacking (MSGS), a technique that built infrastructure from unprocessed regolith particles13. Their findings showed that both the transportation mass and energy requirements were significantly lower than those associated with sintering-based approaches.

However, the use of unprocessed stones for constructing load-bearing structures has so far been investigated only for vertical elements such as free-standing walls and columns without addressing other building components16,17,18,19,20,21,22. A key challenge lies in determining unit arrangement given the inherent irregularity and non-uniformity of unprocessed stones. This challenge falls within the domain of computational design, where algorithms generate construction blueprints based on geometric and physical constraints23,24,25. The materialization of the algorithm-generated blueprints can be further achieved through autonomous construction robots16,26.

This work proposes a computational design method for assembling unprocessed stones within the context of autonomous construction for lunar infrastructure (Fig. 1), which can be decomposed into three sequential phases, including digitalization of in-situ stones to form material stock, computational design for stone arrangement, and physical construction using autonomous robots. Our proposed computational design method iteratively arranges stone layout under both geometric and physical constraints. More specifically, at each iteration, the position and orientation of a candidate stone, randomly selected from the stock, are optimized through an optimization process, and the proposed placement is tested for stability using numerical simulation. If the placement is found feasible, the half-built structure is updated with the newly placed stone in the design space, and the process advances to the next iteration.

The computational design method determines stone positions through an iterative cycle of optimization, simulation, and virtual assembly. The automated workflow blocks are generated using Google Nano Banana by restyling Fig. 3d.

Results

Form-finding for arch-shaped structures

Arches are important architectural elements in terrestrial construction, commonly used in roofs, vaults, buttresses, and as standalone structures such as arched bridges. Many lunar habitat designs also adopt arches as either the roof structure or the primary load-bearing structure2,12,15,27,28. In this section, we built four arches with an inner span of 0.8 meters. The algorithm was allowed to stack stones within a space defined by the inner profile (rounded or triangular) and a rectangular exterior boundary, as illustrated in the first column of Fig. 2, which permitted a maximum thickness of 0.2 meters at the arch base.

ArchRound is constructed with a rounded guiding plane, while ArchTri50, ArchTri60, and ArchTri70 use triangular guiding planes with base angles of 50°, 60°, and 70°, respectively. In the planning visualization, stone colors indicate sequence (blue = earliest placed, red = latest). In the settlement simulation, colors represent velocity magnitude after 5 seconds of simulation under lunar gravity (red = largest, white = smallest).

We used the digital stone stock from ref. 29, which consisted of 146 stones with maximum dimensions ranging from 0.05 to 0.4 meters. These stones were originally scanned for the construction of the digital twin of a stone masonry wall29. Inspired by terrestrial dry-joint masonry practices, we initialized the stones with their shortest dimension aligned in the gravity direction. To mimic a dynamic on-site supply scenario, stones were sampled randomly from the dataset at each construction step. For each sampled stone, 24 poses were considered, generated by rotating the stone around the vertical axis at 30-degree intervals, with and without flipping. The algorithm was executed in parallel for optimizing the placement of each pose. Assembly proceeded until the arch was closed, meaning that stones placed from both sides of the arch came into contact.

Figure 2 presents the arch assemblies generated by the proposed method. Stones are colored according to their construction step: early placements appear in blue, while later placements transition to red. The average step time was 13 seconds to plan one stone, executed on a computer with an Intel Core (TM) i9-13900H processor. The algorithm successfully constructed closed arches in all four cases. Despite the different geometries of the guiding planes (shown as dashed lines), the resulting structures all resemble triangular forms. This is primarily due to the local stability constraint, that a stone should be stably placed on top of other stones, limiting the offsetting between successive courses. ArchRound appears less slender than the other configurations. In its assembly process, the algorithm favors filling the lower portion of the arch rather than completing the upper connection. This behavior comes from the formation of the objective function in the optimization problem, which favors proximity to the boundary when all feasible placements are equally far from the guiding plane.

We also simulated the behavior of the assemblies after arch closure under lunar gravity in the case of a building without binding material, i.e., dry-joint masonry. The last column of Fig. 2 illustrates the configuration of the structure after releasing the stones for five seconds. Stones with large velocity are shown in red. ArchRound and ArchTri70 retained stability, while ArchTri50 and ArchTri60 collapsed from hinge opening, underscoring that stable placement of individual stones during construction does not guarantee global stability after arch closure. Although the stacking algorithm builds arches in a similar way as the construction of corbel arches, which have been proven feasible in historical construction30, the challenge here to maintain stability is amplified by the irregularity of stones and the asymmetry of the resulting geometry. Increasing the arch thickness, as in ArchRound, shows effectiveness by providing counterweight against stone rotation. Another strengthening approach is to introduce an adhesive between stone joints, thereby enhancing joint capacity against bending moments.

Segment-wise planning for the dome structure

Domes are commonly adopted as the global structural form of lunar habitats6,31. This section aims for the construction of a large-scale, 3D dome-shaped structure. The target dome has a span of 2 meters, and its global geometry is a combination of a spherical and a conic form, as illustrated in Fig. 3a. The base of the dome begins with a spherical curvature. When the inward angle reaches 60 degrees, the geometry transitions into a conic shape with a constant inclination of 60 degrees. This design choice is informed by the findings from the previous section, which demonstrated that when the inclination angle falls below 60 degrees, the resulting layout struggles to follow the guiding plane due to the stability constraints of individual stones. The inner surface of the dome acts both as the guiding surface and as the inner boundary for the stacking process. A larger dome defines the outer boundary, resulting in a uniform wall thickness of 0.4 meters. A horizontal plane at the base serves as a fictitious ground to initiate the stacking process.

a Global geometry of the dome, with the inner profile shown in green and the outer profile in grey. b Segment discretization and the extended boundary used for planning one segment. c Planning of one quarter of the dome (black); the converging segment (yellow) is assembled using mirrored boundaries (grey) along ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90°. d Front and sectional views of the planned dome.

To accelerate the computational design process, the dome was discretized into small segments, and stones were assembled segment by segment, as shown in Fig. 3b. For each segment, the actual stacking boundary was extended by 0.2 meters in both width and height to allow the algorithm to account for stones from neighboring segments as boundary conditions. The value of 0.2 meters, approximately the median size of available stones, is an engineering choice that balances computational cost and packing density. Larger values increase the design space and thus the computation time, while smaller values compromise the continuity between segments and create voids in the final structure. The construction sequence proceeded in a clockwise manner at lower heights, followed by upward progression in subsequent layers.

The same stone dataset as in “Form-finding for arch-shaped structures” was used as the composing units. Since the digital stone stock was insufficient to construct the full dome, we assumed that stones could be sampled repeatedly during the assembly process. As a numerical validation study, rather than planning the entire dome, we planned for one quarter of the dome, spanning azimuthal angles between ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90°, as shown by the black segment in the plan view in Fig. 3c. To simulate the planning of the last segment of every layer, where segments from two sides converge, we created fictitious segments after planning each layer by mirroring the placed stones along the axis of ϕ = 0° and ϕ = 90° and planned the converging segment centered at the two axes, as shown in yellow in Fig. 3c.

Figure 3d shows the stone assembly planned for the dome, with stones colored in their assembly sequence from blue to red. The stones exhibit good interlocking behavior, even between neighboring segments. This interlocking is attributed to the incorporation of neighboring segments as boundary conditions in the design of a new segment. By comparing the total volume of the placed stones to the volume of the dome envelope, we obtain a stone filling ratio of 0.62, achieving a similar filling ratio compared to other computational methods for wall construction5,16.

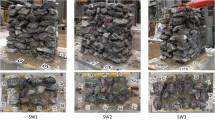

Physical construction of a free-standing wall

Building on the virtual assembly studies, the third case study advances to a physical construction experiment designed to demonstrate the integration of the proposed computational design method in an automated construction workflow. The case study focuses on the assembly of a masonry wall in a layer-wise manner. A robotic masonry construction platform developed in ref. 26, consisting of an ABB IRB 2600 robotic arm and a vision system, was employed for precise stone placement as instructed, while mortar was manually applied at the completion of each layer. We use mortar to reduce the risk of stone falling caused by the sim-to-real gap in robotic manipulation of irregular objects and to ensure stability of the half-built structure throughout the construction process. Construction proceeded in a layer-by-layer sequence, with boundary conditions and ground geometries dynamically updated based on scans from previously placed stones (Fig. 4a). The side boundaries defined the wall dimensions (0.7 m length × 0.4 m width), while the top boundary ensured completion of each layer before advancing. The final wall reached a height of 0.7 m, with individual layer heights ranging from 0.1 to 0.15 m.

A detailed description of the robotic assembly process is provided in our previous work26. a Layer-by-layer planning and assembly process with dynamic boundary conditions. b Robotic stone assembly platform with a dismantable formwork. c The constructed wall measuring 0.7 m × 0.4 m × 0.7 m.

Prior to construction, a stone stock of 150 irregularly shaped limestones was scanned, labeled, and reconstructed to obtain their digital models for computational design. In each assembly step, the algorithm randomly selected one stone from the available stone set, optimized its position, and simulated its stability. The planning of the wall was carried out without including a guiding plane, focusing only on maximizing the proximity between neighboring stones and the proximity between stones and the boundary. Once one layer of stones was planned, the robotic arm carried out the physical assembly, after which mortar was applied manually to cover the top surface of all stones. Then proceeded with the next layer construction. Readers may refer to ref. 26 for a detailed description of the robotic assembly process.

To avoid instability of stones due to the loading of preceding stones, especially before the maturation of mortar, a formwork composed of four timber strips, eight timber panels, and four removable bolted connections was designed and implemented during construction. The timber panels were fixed to the wooden strips, while the wooden strips were connected by removable rivets for fast installation and dismantlement. During construction, the height of the formwork was adjustable by placing additional pads underneath the working plane, as shown in Fig. 4b.

The construction lasted around 30 hours to assemble 138 stones. Figure 4c shows the constructed wall. Out of the 138 stones, 132 stones are assembled successfully with the robotic system, reaching a success rate of 95%, which is much higher than the success rate (86%) reported in ref. 26 with the same robotic system. This improvement is attributed to the stability verification in the planning algorithm, as well as the use of formwork in the construction.

Energy consumption for lunar construction with unprocessed stones

To assess the energy implications of lunar construction with unprocessed stones, we adopted reference values from ref. 5, which reported that transporting and assembling 250 m3 of boulders required approximately 10.4 GJ, corresponding to an energy intensity of 0.0416 GJ/m3. For adhesive joints, we assumed the use of cast regolith as binding material, with an energy requirement of 3.888 GJ/m3 as reported in ref. 32. Based on these values, the energy consumption for dry-joint masonry and mortar-joint masonry can be expressed as functions of packing density p (the volume ratio of stones to the overall structure):

Figure 5 illustrates the evolution of energy consumption per cubic meter as a function of packing density for the two cases. The results indicate that construction using only unprocessed stones requires at least an order of magnitude less energy than methods involving binders. However, as shown in the arch simulations, purely dry-joint stacking faces challenges in achieving global stability due to the irregularity of stones. Nevertheless, the physical wall constructed with a packing density of 0.42 demonstrates that even with mortar, energy consumption is dramatically reduced compared to a pure cast-regolith structure (p = 0). These findings suggest two future directions for reducing the energy requirements of lunar masonry construction: (i) improving stone interlocking to enable more reliable dry-joint assemblies, and (ii) increasing packing density to minimize the volume of binder needed.

Discussion

This study has demonstrated the feasibility of automated lunar masonry construction using unprocessed, in-situ stones. Integrated within a robotic construction workflow, we propose a computational design method that generates execution blueprints for stone assembly across different structural components, including arches, domes, and walls. Our method consistently produces stone layouts that are dense, stable, and buildable, demonstrating its potential as a foundation for lunar masonry construction.

The planned structures can be constructed either with or without binding materials. In the case of dry-joint construction, temporary scaffolding is required to support the half-built structure, as the structural stability of previously placed stones is not considered in the planning of new ones. Nevertheless, the results highlight challenges for dry-joint construction. Simulation based on the Non Smooth Contact Dynamics method for the settlement of arch assemblies under self-weight revealed that stable placement of individual stones does not guarantee global stability after closure. Only half of the designed dry-joint arches remained stable under lunar gravity, while increased element thickness or the introduction of adhesive joints proved effective in enhancing resistance against hinge opening and stone rotation. On the other hand, the physical construction experiment of a mortar-joint wall achieved a 95% success rate in stone placement, confirming that the generated structures can be materialized effectively with the support of temporary scaffolding and cohesive mortar.

A key insight from the arch simulation is that local stability constraints strongly shape the feasible global form. The algorithm consistently generated stable arrangements only when base inclinations exceeded 60°, a threshold that limits the range of constructible geometries and resonates with historical building practice of corbel arches. Extending the framework to incorporate alternative strategies, such as those used for Nubian vault construction33, where stones lean against a gable wall, could expand the design space to arches with smaller base angles.

The energy consumption analysis underscores the efficiency of using unprocessed stones in lunar infrastructure construction. Dry-joint masonry requires at least an order of magnitude less energy than approaches involving binders. Even with mortar, the demonstrated wall remained significantly more efficient than building with pure cast regolith. These results confirm the promise of the construction strategy that uses unprocessed stones with limited binder. However, the present analysis focuses on energy consumption normalized by building volume. To develop a more comprehensive comparison across construction methods, future work should incorporate performance-based metrics, such as load-bearing capacity or serviceability, alongside energy measures. Integrating these additional criteria would require further experimental or numerical investigation, but would enable a more rigorous evaluation of the trade-offs between energy efficiency and load-bearing performance.

Methods

The computational design method iteratively determines the optimal placement of each stone through an optimization formulation that incorporates both geometric and physical constraints. The geometric constraints reflect rules of traditional masonry construction, such as achieving dense packing and maximizing contact surface. The physical constraints ensure that each placement remains stable under gravitational loading.

The proposed method offers two main advantages over existing computational design approaches for building with irregular stones (as summarized in Table 1). First, it provides a universal framework that can be applied not only to vertical elements but also to spanning elements such as arches and domes. Second, it guarantees global optimality in the solution by employing a full search method based on efficient evaluation via discrete convolution. This section presents a detailed description of the method.

Discrete optimization problem

The design space can be discretized into a grid composed of cuboid voxels. A position (x, y, z) in the continuous space corresponds to a voxel (i, j, k) where \(i=\lfloor \frac{x}{\tau }\rfloor ,j=\lfloor \frac{y}{\tau }\rfloor ,k=\lfloor \frac{z}{\tau }\rfloor\), with τ denoting the edge length of each voxel and ⌊⌋ referring to the operation that rounds down the value to the nearest integer. Voxels can be further represented as 3D binary tensors, which numerically encode voxel occupancy. Specifically, we define the following tensors:

-

Ground tensor G: Voxels beneath the ground surface are assigned a value of 1; those above are 0. The voxels occupied by placed stones are also assigned a value of 1 in G.

-

Boundary tensor B: Voxels outside the boundary surfaces are set to 1, while voxels inside are 0.

-

Guiding tensor U: Voxels intersected by the guiding surface are assigned a value of 1; all others are 0.

In addition, we define a local discretized grid for each individual stone, sized to match the stone’s bounding box. This local grid is encoded as a stone tensor S, where voxels occupied by the stone are 1 and all others are 0. Figure 6a illustrates both the mesh and voxel representations of these elements in an arch assembly problem. Based on the discrete representation of the environment, we formulate the placement optimization task as a discrete optimization problem: finding the optimal voxel v (i,j,k) in the space defined by (G, B, U) for placing a given stone S.

Before presenting the full mathematical formulation, we introduce the discrete convolution operation used in this process, defined as:

The operation involves sliding the smaller tensor S (also referred to as the kernel) over the larger tensor G, performing element-wise multiplication followed by summation at each location. The output is a new tensor of the same size as G, where each entry represents the aggregated result of the convolution operation at that location.

When the convolution operation corresponds to a specific metric (e.g., local density or overlap check), the resulting tensor encodes the evaluation of that metric across all possible positions within the space. Since discrete convolution can be computed efficiently using numerical libraries such as SciPy34 or PyTorch35, this allows for evaluating all candidate positions in a single operation. Consequently, the optimization problem can be solved efficiently via brute-force search over the resulting tensor. It should be noted that the search space of a single convolution contains only all positions of one orientation, as the kernel changes once the stone rotates. Considering multiple orientations necessitates carrying out the discrete convolution for each orientation, respectively.

In the following, we propose three types of placement evaluation metrics that are compatible with this convolution operation, as well as an additional metric for evaluating placement stability. They form the overall placement optimization problem detailed in “Optimization problem”.

Proximity

The proximity between two objects quantifies their closeness. To compute the proximity between the stone and the ground, including previously placed stones, we first define an unsigned distance field for the ground:

Here, d(G, v) denotes the shortest Euclidean distance from voxel v to any voxel in the ground that is occupied (i.e., where G = 1). The proximity distance for placing stone S on ground G is then computed via discrete convolution:

The value of PG(v) indicates the degree of proximity between the stone and the ground if the stone were placed at voxel v. Lower values of PG(v) correspond to tighter, denser placements. Following the same formulation, we also define the proximity from the stone to the boundary surface and to the guiding surface, using their respective unsigned distance fields:

Overlapping

To evaluate overlap between two objects, we define an overlap metric based on discrete convolution. The overlap metric between the ground and the stone is calculated as follows:

Here, G is the ground tensor and S is the stone tensor. The value of OG(v) indicates the number of voxels that would overlap between the stone and the ground if the stone were placed at location v. Similarly, the overlap between the stone with the boundary is computed as:

where B is the boundary tensor. The value of OB(v) quantifies how many voxels of the stone would intersect the boundary when placed at position v.

Contact

To detect contact between the current stone and the ground, we first perform a morphological operation on the ground tensor by dilating it in the vertical direction. This is achieved via discrete convolution between the ground tensor G and a vertical dilation kernel V3:

Here, V3 is a vertical dilation kernel of size 3 × 1 × 1, with all elements equal to 1. The dilation expands the occupied region vertically, enabling detection of near-contact without requiring exact voxel overlap. The contact metric is then defined as the convolution between the dilated ground tensor \({G}^{{\prime} }\) and the stone tensor S:

This metric evaluates how many voxels of the stone overlap with the vertically expanded ground, indicating potential contact points. To assess whether specific regions of the stone are in contact, a binary mask M can be applied to the stone tensor prior to convolution:

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication. By using masks that isolate different parts of the stone (e.g., Mleft, Mright, Mfront, Mback), the contact on specific faces of the stone can be identified independently.

Geometric stability

We evaluate the geometric stability of a stone placement by computing the shortest distance from the stone’s center of mass, projected onto the x-y plane, to the convex hull formed by projecting the potential contact points on the ground onto the same plane. This distance is denoted as d(c, s). Figure 6b illustrates an example of verifying the stability of placing stone A on stone B. The potential contact points are defined as the vertices of stone B whose vertical distance to stone A is less than a predefined threshold δ. A larger value of δ allows for greater tolerance between the optimal position obtained from placement optimization and the final position obtained from numerical simulation in latter steps. The value of d(c, s) provides an estimate of the potential moment that could be generated by contact forces at these contact points. We determine whether the placement is geometrically stable by comparing d(c, s) to a threshold α:

Optimization problem

Based on the four types of metrics, we formulate the placement optimization problem as follows:

The objective function minimizes a weighted sum of three proximity distances: proximity from the current stone to the ground (PG), to the boundary (PB), and to the guiding surface (PU). Throughout this study, we use a weight combination of w1 = 1, w2 = 1, and w3 = 0.5.

Regarding constraints in the formulation, the first two ensure that the stone does not overlap with the existing ground or be placed beyond the boundary surfaces. The next four constraints enforce that the left, right, front, and back regions of the stone are all in contact with the ground. The final constraint, denoted by ST = 1, corresponds to the geometric stability condition introduced in “Geometric stability”. Although it cannot be evaluated using discrete convolution, it only needs to be verified for a subset of candidate positions as the prior constraints significantly reduce the feasible space.

Numerical simulation for stability verification

The placement of every single stone during the design process and global stability verification of the final configuration are simulated using the Non-Smooth Contact Dynamics method (NSCD) to verify the stability of the assembly locally and globally. The simulation method is implemented through LMGC90 software36 with Signorini-Coulomb contact law. The stones, modeled as polyhedrons, interact with each other through a point-to-point contact scheme. Figure 6c shows a simulation of placing one stone on top of other fixed stones.

When verifying the local stability during the design process, all previously placed stones and the ground are fixed in all degrees of freedom, while the current stone is released under lunar gravity (i.e. one-sixth of the gravity on Earth). The simulation runs for 5 seconds with a time step of 0.01 seconds with a friction coefficient of 0.6. After the simulation, the orientation and velocity of the stone are compared to predefined thresholds to assess stability. In this study, a placement is considered stable if the stone’s velocity remains below 1 m/s and the angle between the initial frame and the final frame is less than 36 degrees. If the placement is stable, the stone’s final position after simulation is used to update the design space for optimizing the next stone placement. If unstable, the stone is returned to the stock, and the design process proceeds with a new candidate stone.

For global stability verification, the completed structures are simulated under lunar gravity with the ground fixed. Stone-to-stone interactions are modeled as cohesionless contacts with a friction coefficient of 0.6, representing dry-joint assembly. Simulation of the structure when using binding material for strengthening joints is not carried out, as modeling cohesive joints with irregular unit shape is nontrivial and lies beyond the scope of this study.

Data availability

The stone layout generated and analyzed during the current study is available at https://github.com/qianqing-wanggg/StoneDome.git.

Code availability

The Python code used to perform the simulations is publicly available at https://github.com/qianqing-wanggg/StoneDome.git.

References

Ulubeyli, S. Lunar shelter construction issues: The state-of-the-art towards 3d printing technologies. Acta Astronaut. 195, 318–343 (2022).

Zhou, C. et al. Design and automated assembly of planetary lego brick for lunar in-situ construction. Autom. Constr. 118, 103282 (2020).

Zhang, P. et al. Overview of the lunar in situ resource utilization techniques for future lunar missions. Space.: Sci. Technol. 3, 0037 (2023).

Zhou, C. et al. In-situ construction method for lunar habitation: Chinese super mason. Autom. Constr. 104, 66–79 (2019).

Walther, J., Johns, R. L., Kolvenbach, H., Bickel, V. T. & Hutter, M. Autonomous construction of lunar infrastructure with in-situ boulders. Front. Space Technol. 5, 1345337 (2024).

Cesaretti, G., Dini, E., De Kestelier, X., Colla, V. & Pambaguian, L. Building components for an outpost on the lunar soil by means of a novel 3d printing technology. Acta Astronaut. 93, 430–450 (2014).

Caluk, N. & Azizinamini, A. Introduction to the concept of modular blocks for lunar infrastructure. Acta Astronaut. 207, 153–166 (2023).

Khalili, E. N. Lunar structures generated and shielded with on site materials J. Aerosp. Eng. 2, 119–129 (1989).

Makaya, A. et al. Towards out of earth manufacturing: overview of the esa materials and processes activities on manufacturing in space. CEAS Space J. 15, 69–75 (2022).

Bao, C., Zhang, D., Wang, Q., Cui, Y. & Feng, P. Lunar in situ large-scale construction: Quantitative evaluation of regolith solidification techniques. Engineering 39, 204–221 (2024).

Imhof, B. et al. Advancing solar sintering for building a base on the moon (2017).

Khoshnevis, B. Automated construction by contour crafting-related robotics and information technologies. Autom. Constr. 13, 5–19 (2004).

Eckman, E. M., Peck, M. A. & Napp, N. Lunar infrastructure via multiscale granular stacking. J. Spacecr. Rockets 61, 1399–1404 (2024).

Dyskin, A., Estrin, Y., Pasternak, E., Khor, H. & Kanel-Belov, A. The principle of topological interlocking in extraterrestrial construction. Acta Astronaut. 57, 10–21 (2005).

Konstantatou, M., Dall’Igna, M., Wilkinson, S., Gallou, I. & Piker, D. Learning lessons from earth and space towards sustainable multi-planetary design. SPOOL 8, 39–54 (2021).

Johns, R. L. et al. A framework for robotic excavation and dry stone construction using on-site materials. Sci. Robot 8, eabp9758 (2023).

Wang, Q., dos Santos, K. R. & Beyer, K. Geometric planning for masonry wall construction with natural stones using discrete convolution. Eng. Struct. 329, 119695 (2025).

Liu, Y. & Napp, N. Stability-Based Sequence Planning for Robotic Dry-Stacking of Natural Stones. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 8, 5894–5901 (2023).

Shaqfa, M. & Beyer, K. A virtual microstructure generator for 3D stone masonry walls. Eur. J. Mech. - A/Solids 96, 104656 (2022).

Menezes, A., Vicente, P., Bernardino, A. & Ventura, R. From Rocks to Walls: a Model-free Reinforcement Learning Approach to Dry Stacking with Irregular Rocks. https://doi.org/10.1109/cvprw53098.2021.00234 (2021).

Liu, Y., Choi, J. & Napp, N. Planning for Robotic Dry Stacking with Irregular Stones. 321–335, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-9460-1_23 (Springer Singapore, 2021).

Furrer, F. et al. Autonomous robotic stone stacking with online next best object target pose planning. https://doi.org/10.1109/icra.2017.7989272 (2017).

Sun, Q., Reisach, D., Langenberg, S. & Dillenburger, B. A systematic literature review on computational design methods for non-uniform found objects. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4952086 (2024).

Nguyen, M.-N. & Lee, D. Buckling-constrained and stress-based multi-material topology optimization framework for thermoelastic and self-weight structures. Eng. Comput. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00366-025-02209-w (2025).

Nguyen, M.-N., Kang, J., Shin, S. & Lee, D. Robust multi-physical-material topology optimization with thermal-self-weight uncertain loads. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 246, 104319 (2025).

Wang, Q., Wang, J., Rosero, B. G. P., Beyer, K. & Parascho, S. Dynamic planning and assembly for constructing mortar-joint multi-leaf stone masonry walls with a robotic arm. https://doi.org/10.1109/iros60139.2025.11246708 (2025).

Kalapodis, N., Málaga-Chuquitaype, C. & Kampas, G. Structural efficiency of varying-thickness regolith-based lunar arches against inertial loading. Acta Astronaut. 191, 438–450 (2022).

Manos, P., Mehrotra, A. & Konstantatou, M. Stability of Scaffoldless Dry Stone Vaults Under Microgravity and Seismic Loading. 522–531, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-44328-2_54 (Springer Nature Switzerland, 2023).

Saloustros, S. et al. Geometrical digital twins of the as-built microstructure of three-leaf stone masonry walls with laser scanning. Sci. Data 10, 533 (2023).

Roca, P., Lourenço, P. B. & Gaetani, A. Historic Construction and Conservation: Materials, Systems and Damage, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.1201/9780429052767 (2019).

Faierson, E. J., Logan, K. V., Stewart, B. K. & Hunt, M. P. Demonstration of concept for fabrication of lunar physical assets utilizing lunar regolith simulant and a geothermite reaction. Acta Astronaut. 67, 38–45 (2010).

Benaroya, H., Indyk, S. & Mottaghi, S. Advanced Systems Concept for Autonomous Construction and Self-repair of Lunar Surface ISRU Structures. 641–660, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-27969-0_27 (Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2012).

Darweesh, B. & Rael, R. From walls to roofs: formwork-free robotic earthen vault construction. 40–47, https://doi.org/10.2307/jj.11374766.9 (UCL Press, 2024).

Virtanen, P. et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 17, 261–272 (2020).

Ansel, J. et al. Pytorch 2: Faster machine learning through dynamic python bytecode transformation and graph compilation. https://doi.org/10.1145/3620665.3640366 (2024).

Dubois, F. et al. Lmgc90. https://hal.science/hal-00596875v1 (2011).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. conceptualized the study, developed the simulation code, performed data analysis, conducted the experiments, and prepared the initial manuscript draft. J.W. contributed substantially to the experimental work and the revision of the final manuscript. R.X. designed and fabricated the formwork for wall construction and participated in the experimental work. D.D. contributed to the conceptualization and revision of the final manuscript. S.P. and K.B. supervised the study and provided overall guidance throughout the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Wang, J., Xu, R. et al. Computational design for lunar infrastructure built with unprocessed stones. npj Space Explor. 2, 8 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44453-025-00022-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44453-025-00022-9