Abstract

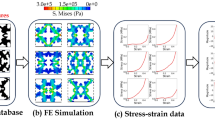

The inverse design of curved truss structures in mechanical metamaterials remains underexplored due to the vast, discrete design space, lack of structural representation, high dimensionality, and inversion ambiguity. This work introduces a geometric AI framework to address these challenges and enable the design of curved cellular structures with targeted effective properties. A graph-based representation is developed and used to generate a dataset of over 200,000 unique structures, combining stiff straight beams with compliant curved elements, guided by tetragonal symmetry. A joint-attributed network embedding variational autoencoder constructs a continuous latent space encoding both topology and geometry, enabling prediction of linear and nonlinear properties. The inverse problem is solved in latent space using gradient-based optimization and a diffusion model conditioned on linear properties. The diffusion model achieves higher accuracy and efficiency, offering a scalable, flexible approach for discovering structures with both compliant and ultra-stiff behaviors and tunable nonlinear responses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Architected materials, also known as mechanical metamaterials, have continuously pushed the boundaries of what is possible in material science, enabling the design of structures with unprecedented mechanical properties1. Advances in additive manufacturing (AM) have facilitated the fabrication of these metamaterials with intricate architectures, thus unlocking novel functionalities such as negative parameters (e.g., negative compressibility2,3, negative Poisson’s ratio4,5, negative stiffness6,7) and multi-stable metamaterials8,9. Traditionally, much of the focus has been on linear truss structures composed of straight bars or struts. AM advancements have opened avenues for designing more complex topologies that incorporate curved elements, such as circular arcs, sinusoidal bars, and parametric curves10. Curved metamaterials have substantial potential for improving mechanical performance. For example, curved truss lattices can enhance compliance11,12,13, reduce stress concentrations14,15, and improve energy absorption13,16,17, positioning them as a compelling frontier in mechanical metamaterial design. However, the design space of curved cellular structures remains largely untapped, especially in three-dimensional (3D), where their potential to discover extraordinary material properties has yet to be fully realized. This presents an exciting opportunity to leverage novel rational design strategies that could unlock the full potential of curved cellular structures and advance the field of architected materials.

The design of truss metamaterials incorporating curved elements presents significant challenges that extend beyond those encountered with traditional linear structures. The complexity of geometry and curvature in curved truss designs often necessitates an intuitive and trial-and-error approach for identification10. State-of-the-art methods rely on iterative forward design processes, where the design is finalized before employing finite element analysis (FEA) to assess properties13,18,19. Forward design is mostly limited to two-dimensional (2D) curved materials14,20 or parametrized 3D surface-based materials18,19,21. In contrast, inverse design, i.e., learning functions that map directly from target material properties to optimal geometry of cellular structures, shortcuts most of the costly iterative simulations, which can accelerate the discovery of new metamaterials at an unprecedented pace. Recent advances in data-driven approaches, machine learning (ML), and artificial intelligence (AI) have significantly facilitated the development of inverse design22,23. However, there are still several challenges to developing inverse design methods for curved cellular structures: (i) the lack of a common design representation for curved cellular structures hinders efficient property space exploration, which also cripples the establishment of a diverse and representative database; (ii) inverse problem is mathematically ill-posed, a solution may not exist, may not be unique, or may be computationally intractable. Learning-based inverse generation brings the inversion ambiguity–multiple topologies can yield the same mechanical behavior, and differentiating “equivalent” designs from the same prescribed target properties is critical to eliminating such ambiguity. (iii) Inverse prediction in a discrete design space is often intractable and computationally intensive. While continuous latent space learning is a widely adopted technique, the transformation between discrete and continuous spaces introduces challenges in identifying a latent space that corresponds to physically valid structures.

To overcome the above challenges, firstly, we propose a graph-based representation for efficient exploration of curved cellular structures in design space and establish a comprehensive database. Recent advances in data-driven approaches have demonstrated significant potential in addressing the inverse problem for straight bar truss materials. However, the effectiveness of these models is heavily contingent on the diversity and representation of the datasets used in ML applications22,23. In many studies, datasets are generated by proposing a limited number of categories and applying geometric modifications to representative unit-cells. This process often involves superimposing different cells, varying diameters, adjusting representative angles, or rotating topologies to expand the material property design space, primarily through parametric representations24,25,26,27,28. Despite these efforts, such representations often fail to encompass a sufficiently broad range of design properties. Notably, a dataset inspired by crystallography 1 achieved extensive coverage, but its volumetric representation is hampered by usability issues. These issues are often exacerbated by common artifacts such as hanging pixels and disconnected geometries, rather than limitations in computational power29. While volumetric representations, including point clouds, have been employed, their application has primarily been confined to a few orthotropic categories, thereby restricting the overall design space 30. In contrast, representing structures as graphs has proven effective for enhancing trainability. Structural lattices can be systematically expressed through graph-based representations, where connection points are treated as nodes and the linking elements—such as struts—are captured as edges within the network22,23,31. In this representation, geometric information is conveyed through the spatial placement of nodes, whereas the topological structure is defined by the pattern of interconnections, often captured using an adjacency matrix. Additional parameters—such as strut thickness or curvature—can also be embedded to enhance the descriptive richness of the graph23. However, the discrete nature of graph networks poses challenges, as connectivity matrices grow quadratically with the number of nodes, limiting their capacity to model patterns with extensive internal connections32. To mitigate this issue, many researchers generate graphs based on small portions of unit-cells, leveraging material symmetry. By defining part of the structure within one symmetric region and reflecting it across symmetry planes, researchers can produce final structures represented by compact graph representations. This method has been successfully applied to cubic unit-cells33,34, orthotropic unit-cells23,35,36, and, more recently, in our previous work, where we identified six distinct symmetry types: cubic, hexagonal, tetragonal, orthotropic, trigonal, and monoclinic22. Building upon the tetragonal data creation method, this work aims to introduce greater anisotropy by incorporating curvature behavior into the design process, thereby enhancing the potential of truss metamaterials.

AI and ML have emerged as transformative tools in property-structure mapping for 3D truss metamaterials. In forward prediction, where structures inform properties, ML techniques accelerate multiscale simulations, effectively predicting both linear37,38 and nonlinear properties35,36,39. In inverse prediction—mapping properties back to structures—physics-guided neural networks (PGNN)7,25,40, reinforcement learning31, and generative models like variational autoencoders (VAEs)41 and generative adversarial networks (GANs)42 have significantly advanced the understanding of structural latent distributions. These models excel at optimizing structures with specified linear25,30,40,43 and nonlinear properties23,28,31. However, PGNNs often yield only a single design for a given target property due to their deterministic nature4,40. Even when multiple deterministic neural networks are used to address the one-to-many mapping challenge in inverse design, such approaches still fall short of capturing the full diversity of valid structural solutions28. Reinforcement learning in discrete spaces requires non-gradient methods such as Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS), which are harder to optimize and more computationally intensive compared to continuous, differentiable approaches31. Additionally, Conditional GANs and Conditional VAEs are susceptible to mode collapse, limiting the diversity of generated designs44,45. Although the latent space provides a continuous and reduced representation that facilitates optimization, when derived from a discrete dataset—as is the case for many truss datasets—unconstrained optimization within this space risks generating invalid truss topologies, as no explicit constraints enforce the validity of the produced samples23. Recently, diffusion generative models have emerged as a potential solution to these challenges. For example,46,47 showcased the capability of a diffusion model to generate 2D materials with nonlinear properties, while34 explored voxel-based truss datasets using a computationally intensive approach that demanded substantial computational resources. To mitigate these issues,26 proposed a latent space diffusion model, although it still contends with challenges related to operations within the latent space. This ongoing exploration into diffusion models may pave the way for more efficient design strategies and enhanced performance in truss metamaterials. To overcome the limitations of the previous generative models and address the aforementioned challenges (ii) and (iii), we propose a geometric AI generative framework for the inverse design of curved mechanical metamaterials. The proposed inverse design pipeline leverages graph-based representations and latent space operations (optimization and diffusion) to generate diverse and structurally valid 3D cellular trusses composed of both curved and straight bars while possessing desired targeted material properties.

In summary, our work presents the first framework, to our knowledge, that addresses the inverse design of 3D truss metamaterials integrating both curved and straight bars. By modeling within the latent space with both constrained diffusion models and gradient optimization, we efficiently address the ill-posed nature of the design problem while avoiding mode collapse, ensuring the generation of diverse and feasible structures. Incorporating nonlinear properties alongside linear ones facilitates distinguishing between structures that may share similar linear properties but exhibit differences in nonlinear behavior. To move beyond the discrete nature of graph-based representations, we use VAE to create a continuous latent space where truss lattices with similar mechanical performance are positioned close to each other. This smooth latent representation enhances design flexibility and improves feature representation. We also employ both generative denoising and gradient-based optimization as a general inverse design process within the latent space, addressing all linear stiffness properties simultaneously. Additionally, a property predictor, trained alongside the VAE, refines the latent space to ensure that generated designs are valid and aligned with desired linear and nonlinear properties. Ultimately, our framework outputs various structures with similar linear properties but distinct topologies and nonlinear performances, offering designers the freedom to choose the most suitable design based on customized requirements. To this end, the main contributions of this work are: (1) developed a graph-based representation to express both straight and curved bars of 3D truss structures, enabling the creation of a diverse dataset of cellular structures; (2) developed a low-dimensional continuous representation of the discrete dataset in original design space, while preserving both linear stiffness and nonlinear compression properties of the structures and allowing refinement during the transition from continuous to discrete representation; and (3) addressed the inversion ambiguity of the ill-posed inverse generation problem by utilizing operations (optimization and diffusion) within the latent space.

Results

Design representation and database establishment

We start by outlining the method used to define the design space of curved structures, which involves two key steps: representing the design by generating cellular structure topologies, and exploring the corresponding property space derived from the constructed database.

Topology creation

Inspired by material symmetries as outlined in ref.22, the dataset creation leverages the inherent tetragonal planes of symmetry to partition the cubic representative volume element (RVE) into 16 symmetrical prisms. This segmentation is achieved through five symmetry planes: three aligned perpendicularly with the primary cubic axes, while the remaining two intersect perpendicularly along the bisector of the first and third primary cube axes48, as depicted in Fig. 1a. This partitioning strategy enables the representation of a structure segment rather than the entire form, significantly simplifying the computational representation while preserving both flexibility and periodic tiling capability. Within each prism, we designate six vertex nodes [v0, v1, v2, v3, v4, v5], nine edge nodes [e0, e1, e2, e3, e4, e5, e6, e7, e8], and five face nodes [f0, f1, f2, f3, f4]. Although the option to define a body node was considered, it was omitted, as its inclusion would not enhance the design space for property modulation. Following prior methodologies 22, vertex nodes are held fixed, while edge nodes possess translational freedom along their respective edges, and face nodes are constrained within their corresponding planes, as illustrated in Fig. 1a.

a Cube decomposition leveraging tetragonal mirror symmetry generates truss patterns with defined node placements and degrees of freedom within each prism. The reflection process results in a tetragonal unit-cell, with a corresponding graph representation where shared nodes are encoded using an adjacency matrix, and node positions are captured in a feature vector. b Implementation of curved structures using Bézier curves: second-order Bézier curves with three control points \({\mathsf{CP}}\) and third-order Bézier curves with four control points \({\mathsf{CP}}\) are used to introduce curvature. The position of the intermediate control points is determined by a curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\), which is also added to the feature vector as a curvature descriptor. c Examples of various tetragonal unit-cells generated by varying the shared nodes within each prism and adjusting the positions of movable nodes. d Examples showcasing different unit-cells achieved by varying the shared nodes and modifying the curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\) within each prism.

The structural configuration of the unit-cell is captured through a graph-based representation, where the shared nodes—modeled as discrete variables—in constructing the unit-cell within each prism are encoded in an adjacency matrix A ∈ {0, 1}n×n with diagonal elements Aii = 0 (for i = 1. . . n) and n = 20 representing the total node count. A matrix entry of 1 indicates a direct edge between nodes, whereas 0 denotes no direct connection. The positions of each movable node are governed by a continuous parameter set, encapsulated within the features’ vector. Additional details are elaborated in the Supplementary Material, which describes strategies for ensuring structural connectivity and defining the weights that determine each node’s position. This setup guarantees structural coherence across boundaries, adhering to the same symmetry principles outlined in prior works22,48. Upon formatting these structures in a representation optimized for ML, reflecting across tetragonal symmetry planes reconstructs a fully symmetrical unit-cell, compliant with tetragonal symmetry principles as seen from Fig. 1a.

After constructing the tetragonal straight bar structure, we applied geometric modifications to introduce curved bars along the vertical direction of the unit-cell. This choice of vertical curvature enhances the compliance of the unit-cell in the vertical direction. For bars aligned vertically within the unit-cell, we refrained from adding curvature to facilitate easier representation and to include configurations with relatively higher stiffness, avoiding excessively compliant structures. To achieve the desired curvature, we utilized Bézier curves, which allow for the creation of free-form curves and surfaces. The shape of a Bézier curve is defined by the positioning of its control points, making it intuitive, flexible, and straightforward to implement49. Complex shapes can be formed by positioning control points effectively, as outlined in50,51. For this purpose, we employed the classic Bézier curve equation:

where \({{\mathsf{CP}}}_{i}\) represents the control points in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{3}\), and \({\mathsf{n}}\) is the order of the Bézier curve. Each \({{\mathsf{CP}}}_{i}\) serves as a Bézier point influencing the shape of the curve. Classical Bézier curves provide smooth approximations, with the curve order dictated by the number of control points50,51. While higher-order Bézier curves allow for more flexibility, they also increase complexity due to the greater number of control points, leading to numerical instability when many points are used52. Thus, for inner bars not vertically aligned with the unit-cell, we employed a third-order Bézier curve with four control points: two at the bar’s ends and two offset by the curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\) along the vertical direction from quarter and three-quarter points between the ends, as shown in Fig. 1b. Also, to ensure periodic boundary conditions, we applied a second-order Bézier curve with three control points for boundary bars: two located at the bar’s ends and a third at the midpoint, shifted by the curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\) along the vertical direction, as shown in Fig. 1b. We implemented the same curvature parameter along all the bars within the same unit-cell and added the value of \({\mathsf{Cr}}\) to the feature vector as information about the curvature of the bars within the unit-cell.

The initial topologies of the truss dataset are defined by the interconnections among distinct nodes within the prism, represented as discrete variables. Subsequently, modifications in the positional offsets of the movable nodes within their constrained regions—captured as continuous variables—serve to expand the possible range of topologies derivable from this dataset, as illustrated in Fig. 1c. Additionally, adjustments to the curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\) further broaden the design space, enabling the generation of structures with more compliance, as demonstrated in Fig. 1d.

Property space of the design dataset

By systematically varying both the discrete and continuous parameters within our representation, we constructed an extensive dataset of lattice structures, comprising over 200,000 unique configurations. For discrete node connections, we employed the Metropolis-Hastings Random Walk sampling technique53. This method transitions between states by randomly selecting neighboring nodes, where the definition of “neighbor” was crucial. Given the relatively modest node count in our setup, we chose a random neighbor definition using an Erdös-Rényi graph with a 50% probability of two nodes being adjacent54. In parallel, the continuous parameter variations involved random perturbations within predefined constrained ranges for node weights, alongside the curvature parameter \({\mathsf{Cr}}\), which was selected from a uniform distribution between 0 and 0.25.

Initially, the generated unit-cells with straight bar configurations conformed strictly to tetragonal symmetry. However, applying curvature after the initial reflection process disrupted this symmetry, resulting in more anisotropic structures. Following the generation of unit-cells, we performed homogenization under periodic boundary conditions to compute the effective mechanical stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\) of the structures. The linear effective stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\) was determined through numerical homogenization55. Full details on the numerical homogenization process and the subsequent calculation of the directional elastic properties can be found in the Methods section. Additionally, nonlinear behavior was assessed by subjecting the structures to uniaxial compressive loading, with a compressive strain applied up to 20% in the z-direction using FEbio software56. The base material for these simulations was assumed to have a Young’s modulus \({{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) = 200 GPa, a Poisson’s ratio \({\nu }_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) = 0.3, and a truss diameter of \({d}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) = 0.025. Details regarding the procedure for obtaining the nonlinear compression response can be found in the Methods section.

To explore the range of mechanical properties achievable by the generated truss structures, we analyzed a representative sample of 5000 unit-cells, including both curved and straight bar configurations. This subset was selected to capture the diversity of the overall design space. Figure 2a illustrates the homogenized relative effective Young’s moduli (\({\mathsf{E}}/{{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)) and shear moduli (\({\mathsf{G}}/{{\mathsf{G}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)), presented on a logarithmic scale along the three principal coordinate axes (1, 2, and 3) and their respective projections onto the 12, 23, and 13 planes. The data showcases an extensive range of mechanical properties, spanning orders of magnitude between 10−6 and 10−2. The red dashed lines represent the Voigt bounds, indicating the theoretical upper limits for the moduli, derived from the base material’s elastic properties and relative densities (\({{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\rm{Voigt}}}=\overline{\rho }\,{{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\) and \({{\mathsf{G}}}_{{\rm{Voigt}}}=\overline{\rho }\,{{\mathsf{G}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\))57.

a Visualization of the normalized effective directional Young’s moduli (\({\mathsf{E}}/{{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)) and shear moduli (\({\mathsf{G}}/{{\mathsf{G}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)) along the three primary axes for a sample of 5000 unit-cells. This representation covers the design space for both straight and curved bar unit-cells, highlighting selected examples with extreme mechanical properties. b Normalized stress (\(\sigma /{{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)) versus strain (ϵ) curves for unit-cells that exhibit similar linear effective stiffness properties but differ significantly in their nonlinear compressive responses. c Distribution of normalized stress (\(\sigma /{{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{s}}}\)) at varying strain (ϵ) levels for the entire dataset, encompassing both straight and curved bar unit-cells.

All unit-cells with straight bars inherently retain tetragonal symmetry, as evidenced by the fact that two out of the three directional relative elastic moduli and shear moduli are equal. In contrast, introducing curvature disrupts this symmetry, resulting in structures that exhibit more orthotropic behavior. Notably, the Poisson’s ratios for these structures are included in the Supplementary Material, which also illustrates the effect of curvature on altering the symmetry properties.

To further differentiate structures that may appear similar in their linear elastic behavior, we also examined their nonlinear responses. This analysis is particularly crucial, as numerous unit-cells exhibit comparable linear stiffness properties but diverge significantly under nonlinear loading conditions, as depicted in Fig. 2b. The additional consideration of nonlinear behavior helps designers address potential confusion about truss material selection, as will be elaborated in subsequent sections. Figure 2c provides a distribution of normalized stress values across all strain levels for the entire dataset. It is evident that structures with consistently lower normalized stress values across various strain levels are predominantly those with curved bars, whereas the configurations with higher normalized stress values are mostly associated with straight bar unit-cells. This distinction emphasizes the role of curvature in enhancing compliance and distributing stress more efficiently under compressive loads, making curved unit-cells more suitable for energy absorption applications. It highlights the novelty of curved unit-cell designs over those with straight bars and underscores the importance of having a design tool capable of predicting both compliant (curved) unit-cells and stiff (straight) unit-cells. The influence of curvature on the unit-cell is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Generative design algorithms

In this subsection, we begin by describing the developed algorithm to construct the latent space of curved structures using a VAE, establishing a relation between the compact latent representation and the corresponding mechanical properties. Subsequently, we demonstrate the inverse design framework, leveraging gradient-based optimization within the latent space and generative modeling via a latent diffusion model.

Low-dimensional latent space learning

The design space for curved truss structures is inherently discrete and discontinuous. To address this complexity, we represent the truss lattices as a graph structure \({\mathsf{G}}=({\mathsf{A}},{\mathsf{x}})\), where \({\mathsf{A}}\) denotes the adjacency matrix encoding the discrete connectivity of the structure, and \({\mathsf{x}}\) represents the feature vector with continuous attributes (see Fig. 1b). This formulation enables machine learning (ML) models to take \({\mathsf{A}}\) and \({\mathsf{x}}\) as inputs and construct a compact, continuous latent space that captures the essential features of the original high-dimensional and discrete structural graph.

To enable this transformation, we employ a VAE41, which consists of an encoder and a decoder. The input graph \({\mathsf{G}}=({\mathsf{A}},{\mathsf{x}})\) is processed by an encoder network parameterized by a set of trainable variables ϕ. Rather than generating a deterministic latent code directly, the encoder outputs the parameters of a probabilistic distribution over the latent space. Specifically, it produces two vectors in \({{\mathbb{R}}}^{{\mathsf{d}}}\): the first, \(\mu ({\mathsf{G}};\phi )\), represents the central tendency of the distribution, while the second, \(\sigma ({\mathsf{G}};\phi )\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{\mathsf{d}}}\), characterizes its deviation. Together, these define a diagonal multivariate Gaussian from which the latent vector \({\mathsf{z}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{\mathsf{d}}}\) is drawn.

To reverse the encoding process, the decoder network, defined by the trainable parameters θ, takes the latent vector z as input and reconstructs a graph \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{{\prime} }=({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{\prime} },{{\mathsf{x}}}^{{\prime} })\) that approximates the original graph \({{\mathsf{G}}}=({{\mathsf{A}}},{{\mathsf{x}}})\) in both adjacency matrix and feature vector. Since the topology of the structure is influenced by the interplay between the adjacency matrix and the feature vector, it is crucial to capture both their individual contributions and their combined dependencies. The vanilla variational graph autoencoder (VGAE)58 assumes a fully congruent relationship between the adjacency matrix and the feature vector, where each node is uniformly parameterized and structural dependencies are reflected directly in the feature vector. However, this assumption does not hold in our setting. Specifically, edge node positions are defined by a single parameter, face node positions require three parameters, and curvature is represented by an additional parameter that is entirely independent of the adjacency matrix (see Supplementary Material for details). To effectively model this heterogeneous representation, we adopt the attributed network embedding framework proposed by Lerique et al.59, which disentangles and captures both the independent and shared contributions of the adjacency matrix and the feature vector information. This approach was also implemented in similar work by Zheng et al.23. In this approach, the adjacency matrix and feature vector are processed separately through distinct encoders, producing their respective latent space parameters: \({\mu }_{{\mathsf{A}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}}}\), \({\sigma }_{{\mathsf{A}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}}}\) for the adjacency matrix, and \({\mu }_{{\mathsf{x}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}}}\), \({\sigma }_{{\mathsf{x}}}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}}}\) for the feature vector, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The resulting latent distribution is formed through partial integration of the encoded representations of the adjacency matrix and feature vector. This shared latent representation is characterized by the combined parameters μ and \(\log \sigma \in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{{\mathsf{d}}}\), where the dimensionality is given by \({\mathsf{d}}={{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}}+{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}}-{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{Ax}}}\):

a The attributed network embedding VAE model processes the truss lattice structure \({\mathsf{G}}=({\mathsf{A}},{\mathsf{x}})\), defined by the adjacency matrix \({\mathsf{A}}\) and feature vector \({\mathsf{x}}\). The adjacency encoder \({{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}\phi }\) and feature encoder \({{\mathsf{E}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}\phi }\) map \({\mathsf{G}}\) to a shared latent space \({\mathsf{z}}\), which follows a normal distribution. This reduced representation is passed to the adjacency decoder \({{\mathsf{D}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}\theta }\) and feature decoder \({{\mathsf{D}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}\theta }\) to reconstruct \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{{\prime} }=({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{\prime} },{{\mathsf{x}}}^{{\prime} })\). A property predictor \({{\mathsf{P}}}_{\omega }\) uses \({\mathsf{z}}\) to estimate the effective stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\) and nonlinear stress-strain response σ(ϵ) of the curved trusses. The figure shows the prediction accuracy for both properties. b Prediction performance is also evaluated specifically for \({\mathsf{C}}\). c A gradient-based optimization framework in the latent space \({\mathsf{z}}\) generates curved trusses with target properties. Starting with an initial guess, optimization searches for valid structures matching desired properties. The candidate structures are encoded, their latent representations predicted, and validity ensured. d Two examples demonstrate the process, starting from random latent points, optimizing to achieve target \({\mathsf{C}}\), and showing intermediate optimization steps.

Here, ⊕ represents vector concatenation. The term \({{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{A}}}-{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{Ax}}}\) corresponds to the number of latent dimensions dedicated exclusively to capturing the individual dependencies of the adjacency matrix on the final structure. Similarly, \({{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{x}}}-{{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{Ax}}}\) represents the dimensions allocated solely to the feature vector’s independent influence on the structure, while \({{\mathsf{d}}}_{{\mathsf{Ax}}}\) denotes the dimensions reserved for the shared dependencies between the two. In the overlapping approach, the latent space can capture correlations between the adjacency matrix and feature vector more directly, avoiding the redundancy seen in separate (non-overlapping) encodings. This design enables control over how their mutual influence is expressed, all while keeping the number of trainable parameters unchanged59. Furthermore, the latent space is intrinsically linked to the effective linear stiffness properties, \({\mathsf{C}}\), and the nonlinear stress-strain response under compression, σ(ϵ), of the structures. Leveraging this relationship enables the elimination of high-cost procedures such as finite element (FE) homogenization55 and direct compression simulations60. To achieve this, we incorporate a property predictor network, parameterized by \({\omega }\), which maps the latent encoding to the corresponding physical property values, thus offering accurate estimations with minimal computational overhead.

Here, θ, ϕ, and ω represent the model parameters of the VAE, while λ serves as a weight factor to prioritize the accurate reconstruction of graph topology. The reconstruction loss ensures that the decoder faithfully reproduces the original graph, preserving both the adjacency matrix and the feature vector. Training the model involves three coordinated objectives. The first focuses on structural fidelity: the reconstruction loss measures how well the decoder restores both the adjacency matrix and the feature vector from the latent encoding. The second objective involves predictive accuracy, where the property predictor learns to estimate target responses—specifically, the linear stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\) and the compressive stress–strain curve σ(ϵ)—from the latent representation. The third component introduces a regularization term via the Kullback–Leibler41, which encourages the latent distribution to remain close to a standard normal distribution, \({\mathcal{N}}(0,I)\). This constraint facilitates smooth sampling from the latent space, enabling the model to generate new, physically plausible curved truss designs beyond the original dataset. As a result, the latent space organizes topologies such that structurally similar designs with comparable properties are positioned in close proximity, ensuring meaningful and continuous transitions within the design space.

The generative capability of the VAE allows for the reconstruction of unseen structures during the training process, with an accuracy score higher than 0.999 for the adjacency matrix and \({{\mathsf{R}}}^{2}\ge 99 \%\) for all the parameters in the feature vector (see Supplementary Material for details). In parallel, the property predictor \({{\mathsf{P}}}_{\omega }\) enables efficient estimation of the mechanical properties—linear stiffness and nonlinear compression response—of the reconstructed structures. As shown in Fig. 3a, the reconstructed structures achieve predictive accuracies of \({{\mathsf{R}}}^{2}\ge 97.5 \%\) for orthotropic stiffness components and \({{\mathsf{R}}}^{2}\ge 98 \%\) for stress values. Comprehensive parity plots showing the prediction performance of both predicted properties are included in the Supplementary Material. These results demonstrate the framework’s ability to reliably correlate structural topology with mechanical performance, enabling efficient exploration of the design space.

Figure 3b illustrates that training the model with only effective linear stiffness components achieves \({{\mathsf{R}}}^{2}\ge 98.5 \%\), but incorporating compression properties adds critical differentiation between structures with identical linear behavior. This allows designers to generate multiple designs with the same target stiffness but varying nonlinear characteristics, offering more flexibility in material selection and functional optimization. We also showed in the Supplementary Material the effectiveness of the model when trained only on nonlinear compressive stress-strain response. While this framework addresses the structure-to-property (forward) prediction, the inverse property-to-structure problem remains inherently challenging due to the one-to-many mapping from property space to topology space, necessitating advanced methodologies for its resolution.

Latent space—gradient-based optimization

The continuous latent space enables gradient-based optimization to tailor curved structures for desired effective stiffness performance and extrapolate beyond the training domain. This involves identifying potential candidates whose reconstructed stiffness matches the queried target23,40. To generate physically realistic truss structures or compute property sensitivities with respect to structural features, automatic differentiation and backpropagation are employed to calculate gradients within the VAE’s latent space.

However, the discrete structure of curved truss topologies makes latent space optimization inherently challenging. Without explicit constraints during optimization, reconstructed designs may exhibit mechanical responses—such as effective stiffness—that diverge from their intended targets. To handle this, we implement an indirect correction mechanism: once a latent code is optimized, the corresponding truss structure is decoded, re-encoded to refine the latent representation, and then evaluated through the property predictor to estimate both the linear stiffness tensor and the nonlinear stress–strain behavior under compression (Fig. 3c). This encoding-decoding process ensures that the proposed structures exhibit linear stiffness properties similar to the target values. While the optimization focuses on achieving target linear stiffness, compression properties are simultaneously evaluated throughout the process, enabling the generation of designs with similar linear performance but varying nonlinear behaviors. The full inverse design capability of latent space optimization is discussed in subsection “Inverse Generative Design Evaluation”, but Fig. 3d illustrates its effectiveness. Given the one-to-many mapping from properties to structures, we randomly selected two latent points, gradient-based optimization refines both points to match the target elastic performance. Optimizations for each point are performed in parallel, running for up to 1000 cycles or until convergence. It should be mentioned that optimization to obtain unit-cells with a desired nonlinear compression response is straightforward, as the latent space preserves both stiffness and compression properties. However, our approach identifies multiple valid candidate truss structures with similar linear mechanical behavior but distinct nonlinear compression responses, offering flexibility in selecting optimal designs.

Latent space—diffusion model

We address the inverse design of curved truss structures using diffusion models that operate within the latent space61,62,63. Compared to other generative models, diffusion models are less prone to mode collapse, ensuring a more diverse and reliable exploration of the design space, which addresses the one-to-many mapping issue64. These models leverage a stochastic forward process that progressively corrupts the latent representation z of the structural topology into pure Gaussian noise, and a reverse process that reconstructs the desired structure latent by denoising the Gaussian noise62. This framework enables the generation of structurally valid designs conditioned on specified mechanical properties, such as effective stiffness tensors, while maintaining computational efficiency.

The diffusion process is modeled as a fixed Markov chain with Gaussian transitions. At each time step t, noise sampled from a Gaussian distribution is added to the latent variable \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}-{\mathsf{1}}}\):

The variance schedule \({\beta }_{{\mathsf{t}}}\) satisfies \(0 < {\beta }_{1} < \cdots < {\beta }_{{\mathsf{t}}} < 1\). Through this process, the latent variable \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{0}\) at step t becomes increasingly noisy, until it approaches a standard Gaussian distribution \({\mathcal{N}}(0,{\bf{I}})\) at \({\mathsf{t}}={\mathsf{T}}\). The forward process is fixed, and thus, \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}}\) can be obtained directly from \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{0}\) during training:

To sample directly at any time step, \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}}\) is expressed as \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}}=\sqrt{{\bar{\alpha }}_{{\mathsf{t}}}}\,{{\mathsf{z}}}_{0}+\sqrt{1-{\bar{\alpha }}_{{\mathsf{t}}}}\,{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }},\) where \({\boldsymbol{\epsilon }} \sim {\mathcal{N}}(0,{\bf{I}})\), \({\alpha }_{{\mathsf{t}}}=1-{\beta }_{{\mathsf{t}}}\), and \({\bar{\alpha }}_{{\mathsf{t}}}=\mathop{\prod }\nolimits_{i = 1}^{{\mathsf{t}}}{\alpha }_{i}\).

The reverse process approximates \({\mathsf{q}}({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}-{\mathsf{1}}}| {{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}})\) using a neural network \({{\mathsf{p}}}_{\eta }({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}-{\mathsf{1}}}| {{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}})\), parameterized by η:

Here, μη denotes the learned mean output, while the covariance matrix Σ is not learned but fixed explicitly as a function of time: \({\boldsymbol{\Sigma }}({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}},{\mathsf{t}})=\frac{1-{\bar{\alpha }}_{{\mathsf{t}}-{\mathsf{1}}}}{1-{\bar{\alpha }}_{{\mathsf{t}}}}{\beta }_{{\mathsf{t}}}{\bf{I}},\) this parametrization follows the formulation in 64. The model is trained to predict the noise ϵη added during the forward process by minimizing \({{\mathcal{L}}}_{{\rm{LDM}}}={{\mathbb{E}}}_{{\mathsf{t}},{{\mathsf{z}}}_{0},{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}[{\Vert {\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}-{{\boldsymbol{\epsilon }}}_{\eta }({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}},{\mathsf{t}})\Vert }^{2}]\). When conditioned on mechanical properties, the loss function becomes:

Both ϵη and \({{{\tau }_{\psi}}}\) are jointly trained, where \({\tau }_{\psi}\) represents the property encoder parameterized by ψ and maps the effective stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\) to a feature vector y by utilizing a multi-layer perceptron \({\bf{y}}={\tau }_{\psi }({\mathsf{C}})\). This feature vector is then concatenated with the latent variable \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}}\) at each diffusion step \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{{\mathsf{t}}}}^{{\rm{cond}}}={\rm{Concat}}({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}},{\bf{y}})\). In addition, sinusoidal positional embeddings are used to produce a unique representation for each time step \({\mathsf{t}}\), which is then fed alongside \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{{\mathsf{t}}}}^{{\rm{cond}}}\). Once the denoising neural network ϵη is trained, new data is generated by sampling a vector of pure noise \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{T}}}\) from a standard normal distribution, and the trained network is used to gradually denoise it (based on the conditional probability it has learned). The denoised vector is then transformed into a structure by passing it through the VAE decoders. For further information about the latent diffusion model, the reader is referred to61,62. This setup ensures that the model can generate structures tailored to specific mechanical properties by effectively modeling the conditional distribution \({\mathsf{p}}({\mathsf{z}}| {\mathsf{C}})\), the latent diffusion process operates within the low-dimensional latent space derived from the VAE, significantly reducing computational costs compared to direct diffusion in the high-dimensional structural graph. This enables the model to be trained efficiently on a single GPU or a small number of GPUs, unlike standard diffusion models that demand substantial computational resources.

However, due to the discrete nature of truss topologies, unconstrained diffusion within the latent space may generate structures with reconstructed stiffness properties that deviate from the target values, as no explicit constraints ensure validity throughout the denoising process. To address this, we adopt an indirect approach during inference: curved truss structures are first reconstructed from their denoised latent representation, passed through the encoder to refine the latent variables, and then forwarded to the property predictor to estimate both effective stiffness and nonlinear compression properties (Fig. 4b). While the inverse diffusion framework primarily targets linear stiffness components, nonlinear compression properties are concurrently evaluated throughout the process. This enables the generation of designs with similar linear stiffness properties but varying nonlinear behaviors, as illustrated by the two examples in Fig. 4b.

a The training process of the graph latent diffusion model for reconstructing curved truss structures \({\mathsf{G}}=({\mathsf{A}},{\mathsf{x}})\). The VAE encoders \({\mathsf{G}}\) to a shared latent space \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{0}\). Gaussian noise is gradually added to \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{0}\) through the noising process \({\mathsf{q}}({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{T}}}/{{\mathsf{z}}}_{0})\), resulting in the fully noised latent representation \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{T}}}\), which follows a standard Gaussian distribution \({\mathcal{N}}(0,I)\) at \({\mathsf{t}}={\mathsf{T}}\). Subsequently, the denoising process removes noise from the noised latent \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{T}}}\) using a neural network \({{\mathsf{p}}}_{\eta }({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}-{\mathsf{1}}}/{{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{t}}})\), constrained by the effective stiffness tensor components encoded into an embedding via the property encoder τψ, to reconstruct the latent representation \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{0}}^{{\prime}}\). The denoised vector \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{0}}^{{\prime}}\) is then transformed into a structure \({{\mathsf{G}}}^{{\prime} }=({{\mathsf{A}}}^{{\prime} },{{\mathsf{x}}}^{{\prime} })\) by passing it through the VAE decoders. b The inverse design framework demonstrates the conditioning of the denoising process starting from random noise \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{\mathsf{T}}}\) to reconstruct the unconstrained latent space \({{\mathsf{z}}}_{{0}}^{{\prime}}\). The unconstrained latent space is constrained through the VAE decoders and encoders to produce a latent space that generates valid structures. The figure also illustrates two examples of random vectors sampled from a standard Gaussian distribution and the intermediate denoising steps leading to valid structures with reconstructed effective stiffness tensors closely matching the target properties.

Inverse generative design evaluation

To evaluate the capabilities of our inverse design models, we apply the proposed generative modeling frameworks to design truss structures on an unseen dataset—randomly split from the full data—to ensure balanced coverage of the property space and avoid poor extrapolation performance, which is a known limitation of data-driven models. The dataset comprises 2000 structures sampled from the testing set, as illustrated in Fig. 5. Both methods aim to identify truss topologies whose effective stiffness tensors closely match a target stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\), while ensuring structural feasibility and computational efficiency.

Inverse prediction accuracy for 2000 unseen testing samples, where 50 samples were generated for each testing point. The results are represented by the best sample’s coefficient of determination \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{best}}}^{2}\) compared to the target samples, reconstructed sample distributions measured using the Wasserstein distance \({\mathsf{W}}\) relative to the target distribution, and 95% confidence interval predictions based on the 50 reconstructed samples for 100 unseen target stiffness tensors \({\mathsf{C}}\). Additionally, the mean prediction accuracy \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{mean}}}^{2}\) is computed using the mean values of the 50 reconstructed samples for each target tensor. The three sets of figures illustrate inverse reconstruction results using: a gradient-based optimization within the latent space, and b the diffusion framework within the latent space.

Figure 5a illustrates the results obtained through gradient-based optimization within the VAE’s latent space. The optimization process was performed over 100 cycles, generating 50 candidate samples per target stiffness tensor while accounting for the one-to-many mapping of properties to structures. This method iteratively refines the latent variables to produce reconstructed structures that align with the desired mechanical properties. The total runtime for optimizing all samples was 13 h and 43 min on a CPU using 10 cores. Figure 5b presents the results obtained using the latent diffusion model. For each target stiffness tensor, 50 samples were drawn from a standard Gaussian distribution, and noise was gradually removed over 100 time steps. The denoising process is conditioned by the target stiffness tensor, resulting in reconstructed latent vectors that are transformed into structures conditioned on the specified target stiffness tensor \({\mathsf{C}}\). The training and inference of the diffusion model required a total of 1 h and 52 min on a single GPU.

The spider plots in Fig. 5 provide a detailed overview of the effective stiffness tensor prediction accuracy for the reconstructed structures. These results are evaluated by identifying the reconstructed sample whose effective stiffness tensor most closely matches the target tensor based on the normalized mean square error (NMSE). The prediction accuracy across the testing dataset, when compared with the reconstructed sample that achieves the lowest NMSE, is captured by \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{best}}}^{2}\). Figure 5a, b also depict the final reconstructed distributions for \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{11}\), \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{12}\), \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{13}\), \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{22}\), and \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{33}\), compared with the target distributions both graphically and through the use of the Wasserstein distance \({\mathsf{W}}\)65. The final row in Fig. 5 shows the 95% confidence interval of the prediction accuracy, based on all 50 samples generated for each target stiffness tensor component from the unseen testing dataset. The mean value of the reconstructed components is compared with the target component to calculate \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{mean}}}^{2}\). Additionally, the 95% prediction accuracy for \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{44}\), \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{55}\), and \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{66}\) is illustrated. Detailed distribution plots and prediction accuracy results for the remaining stiffness components are provided in the Supplementary Material. This also includes the prediction accuracy across all 50 generated samples for each target stiffness tensor, quantified using \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{all}}}^{2}\). The prediction accuracy for the orthotropic stiffness components, based on the sample achieving the lowest NMSE across all components, is \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{best}}}^{2}\ge 77 \%\) for most components, except for \({{\mathsf{C}}}_{23}\), where it is approximately 0.6, when utilizing inverse optimization within the latent space. In contrast, \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{best}}}^{2}\ge 95 \%\) for all orthotropic components when applying the inverse denoising framework. The 95% prediction interval is notably larger for predictions obtained using latent space optimization compared to those generated through the latent diffusion model. Specifically, the mean prediction accuracy for the orthotropic components is \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{mean}}}^{2}\ge 46 \%\) with latent space optimization, whereas it achieves \({{\mathsf{R}}}_{{\mathsf{mean}}}^{2}\ge 92 \%\) with conditional latent diffusion.

The reconstructed distributions for the stiffness components obtained through latent space optimization yielded promising results, with Wasserstein values for all reconstructed components satisfying \({\mathsf{W}}\le 0.03\). However, for the diffusion process, the Wasserstein values for all reconstructed components are significantly lower, with \({\mathsf{W}}\le 0.006\). In addition, to demonstrate the reconstruction accuracy of the entire stiffness tensor, we show in the Supplementary Material that 35.34% of the reconstructed structures have NMSE values less than 0.05 when using gradient-based optimization within the latent space, and around 96.68% when using the latent diffusion model. These findings demonstrate that the latent diffusion model outperforms the optimization-based approach in both prediction accuracy and consistency of the reconstructed properties. The high \({{\mathsf{R}}}^{2}\) values and narrow confidence intervals achieved by the latent diffusion method underscore its effectiveness in generating physically realistic truss structures with precise mechanical properties. Compared to a standard dataset-based search for the closest property matches, the diffusion model generated more samples with properties closer to the target unit cell, demonstrating a stronger ability to effectively explore the design space—despite requiring more inference time, as detailed in the Supplementary Material. Moreover, the latent diffusion model outperformed the optimization-based approach even when conditioned on the nonlinear compressive stress-strain response, as shown in the Supplementary Material. It is worth noting that increasing the number of optimization cycles in the latent space beyond 100 (e.g., to 1000 cycles) would likely yield improved results. However, the choice to limit the optimization to 100 cycles ensures consistency in comparing the two models. This approach emphasizes the diffusion model’s advantage, as its stochastic nature and ability to explore the latent space prevent it from getting stuck in local minima, a common limitation of optimization-based methods. These findings establish the latent diffusion approach as a reliable and efficient tool for inverse design, enabling designers to effectively explore the curved truss design space while simultaneously satisfying both linear mechanical property requirements and nonlinear performance objectives.

Discussion

This work presented an inverse design paradigm for mechanical metamaterials with curved truss structures. The proposed generative modeling framework constructs curved truss metamaterials by leveraging topology optimization within the latent space and a latent diffusion model. We developed a dataset based on tetragonal material symmetry, initially creating straight bar unit-cells with high stiffness and subsequently introducing curvature parameters that define the bars as Bézier curves based on their spatial locations. This transformation resulted in a dataset comprising both stiff, straight bar truss structures and compliant, curved truss materials. To efficiently map the high-dimensional structural information into a low-dimensional latent space, we employed a joint attributed network embedding VAE. This VAE integrates information from both the adjacency matrix and the feature vector, constructing a shared, continuous latent space as opposed to the inherently discrete nature of the original data. Furthermore, the VAE was jointly trained with a property predictor network, allowing the direct estimation of effective stiffness tensors and nonlinear compression responses from the latent variables. This approach addresses the forward problem of predicting structures’ properties and solving the inverse problem simultaneously.

The inverse design was addressed with two approaches: (1) optimization in the latent space, and (2) latent diffusion model. In both methods, the shared latent space was constrained to ensure the generation of valid truss structures. Conditioning was applied based on the effective stiffness tensor components, while each latent point retained information about both stiffness and nonlinear compression properties, allowing designers to select structures with identical stiffness components but differing nonlinear performance. The results demonstrate that the latent diffusion model significantly outperformed latent-space optimization in both point-wise predictions and distribution accuracy when tested on unseen datasets. The diffusion model not only achieved higher accuracy but also exhibited superior computational efficiency, making it more suitable for large-scale generative design tasks.

The proposed framework can be extended to construct aperiodic curved truss structures by introducing constraints on the reconstructed adjacency matrix to preserve connectivity. Additionally, inverse tools ensure that generated designs satisfy prescribed performance requirements. Incorporating other material symmetry design criteria—such as cubic, hexagonal, orthotropic, and other symmetry classes—which can be represented using a format similar to that of the tetragonal class22, would further enable the creation of larger datasets encompassing a broader range of mechanical properties, thereby expanding the design space. Furthermore, the continuous representation of the latent space and the robust performance of the latent diffusion model open up new avenues for the discovery of advanced metamaterials. This framework provides a flexible tool for designing truss structures, offering the capability to generate both compliant materials and ultra-stiff structures with tailored nonlinear responses.

Methods

Effective stiffness tensor

Numerical homogenization is a computational technique extensively employed to determine the homogenized macroscopic mechanical properties of cellular structures, with a particular focus on deriving the elasticity stiffness tensor55. The primary motivation for selecting the stiffness tensor as a representative metric for effective mechanical properties stems from its ability to capture all elastic constants via established approximation methods 1. The numerical homogenization process involves solving the equation below, where \({{\mathsf{E}}}_{ijpq}\) denotes the stiffness tensor, Ω represents the volume of the cellular structure, and ϵij corresponds to the strain field within the virtual displacement framework. Here, \({\epsilon }_{pq}^{0(kl)}\) indicates the prescribed macroscopic strain, while ν and χkl denote the virtual and unknown displacement fields, respectively. For a comprehensive analysis of 3D cellular materials, the equation below must be solved under six independent loading scenarios, encompassing three axial and three shear deformation cases. A detailed methodological explanation can be found in reference55.

Applying the homogenization approach results in a 6 × 6 elastic stiffness tensor, denoted as \([{{\mathsf{C}}}_{ij}]\). For subsequent analyses, the compliance tensor \([{{\mathsf{S}}}_{ij}]\) = \({[{{\mathsf{C}}}_{ij}]}^{-1}\) is used to derive the directional elastic constants for any 3D unit-cell configuration, as detailed in the equations below 1:

This methodology offers a systematic framework for computing all relevant elastic moduli and Poisson’s ratios, thereby enabling the comprehensive characterization of the mechanical properties for diverse unit-cell structures.

Compression stress–strain simulation

To characterize the effective nonlinear response of our curved truss structures, we employed FEA using the open-source software FEBio56. The simulation framework was designed to extract the 3D stress-strain behavior of the unit-cells under uniaxial compression, leveraging principles of computational analysis with rotational constraints imposed on all surfaces and periodic boundary conditions applied to displacements along the four lateral faces. The unit-cells were positioned between two rigid plates: a displacement boundary condition was applied at the top surface in the negative z-direction, while the bottom surface remained fixed. The truss structures were modeled using isotropic linear elastic material properties, defined by a Young’s modulus of 200 GPa and a Poisson’s ratio of 0.3. A compressive strain of up to 20% was applied in incremental steps, with an implicit static solver used to ensure convergence, particularly under conditions of large deformation. The simulation employed 15 discrete time steps, each corresponding to a specific strain value, with adaptive control to address potential numerical challenges, such as localized buckling. The effective compressive stress was obtained by summing the reaction forces along the z-axis at the nodes in contact with the top plate. These reaction forces, combined with the applied displacements, were used to derive the stress-strain curve for each structure. To enhance the efficiency of subsequent analyses, we selected representative stress values at specific strain increments (e.g., ϵ = 1.33%, 2.66%,...,20%) and reduced the dimensionality of the resulting data through interpolation. This streamlined representation of the compressive behavior ensures that critical mechanical properties, such as strain hardening and localized buckling, are captured efficiently for applications in soft robotics and energy-absorbing systems.

Generative model framework

Details of the VAE and diffusion model architectures, along with their optimized hyperparameters (e.g., number of layers, hidden units, activation functions, noise schedule, training epochs, etc.), are provided in the Supplementary Material, including an overview of the computational runtime and hardware resources used during training and inference.

Data availability

The data created in this study are available on GitHub: https://github.com/DreamLabUIC/Inverse-Design-of-Curved-Truss-Material.

Code availability

The code used in this study is available upon request directly from the corresponding author.

References

Lumpe, T. S. & Stankovic, T. Exploring the property space of periodic cellular structures based on crystal networks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2003504118 (2021).

Yao, Y. et al. A multifunctional three-dimensional lattice material integrating auxeticity, negative compressibility and negative thermal expansion. Compos. Struct. 337, 118032 (2024).

Qu, J., Gerber, A., Mayer, F., Kadic, M. & Wegener, M. Experiments on metamaterials with negative effective static compressibility. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041060 (2017).

Abu-Mualla, M., Jiron, V. & Huang, J. Inverse design of two-dimensional shape-morphing structures. J. Mech. Des. 145, 121703 (2023).

Xu, X. et al. Adjustable ultra-light mechanical negative Poisson’s ratio metamaterials with multi-level dynamic crushing effects. Small 20, 2403082 (2024).

Tan, X. et al. Novel multi-stable mechanical metamaterials for trapping energy through shear deformation. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 164, 105168 (2019).

Corsi, M., Bagassi, S., Moruzzi, M. & Weigand, F. Additively manufactured negative stiffness structures for shock absorber applications. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 29, 999–1010 (2022).

Alturki, M. & Burgueño, R. Response characterization of multistable shallow domes with cosine-curved profile. Thin-Walled Struct. 140, 74–84 (2019).

Jeong, H. Y. et al. 3d and 4d printing of multistable structures. Appl. Sci. 10, 7254 (2020).

Álvarez Trejo, A., Cuan-Urquizo, E., Bhate, D. & Roman-Flores, A. Mechanical metamaterials with topologies based on curved elements: an overview of design, additive manufacturing and mechanical properties. Mater. Des. 233, 112190 (2023).

Bai, Y. et al. Mechanical properties of a chiral cellular structure with semicircular beams. Materials 14, 2887 (2021).

Li, K., Seiler, P., Deshpande, V. & Fleck, N. Regulation of notch sensitivity of lattice materials by strut topology. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 192, 106137 (2021).

Gao, Z. et al. Data-driven design of biometric composite metamaterials with extremely recoverable and ultrahigh specific energy absorption. Compos. Part B Eng. 251, 110468 (2023).

Niknam, H., Yazdani Sarvestani, H., Jakubinek, M., Ashrafi, B. & Akbarzadeh, A. 3d printed accordion-like materials: a design route to achieve ultrastretchability. Addit. Manuf. 34, 101215 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Cell-size graded sandwich enhances additive manufacturing fidelity and energy absorption. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 211, 106798 (2021).

Wu, Y., Sun, L., Yang, P., Fang, J. & Li, W. Energy absorption of additively manufactured functionally bi-graded thickness honeycombs subjected to axial loads. Thin-Walled Struct. 164, 107810 (2021).

Yin, H., Guo, D., Wen, G. & Wu, Z. On bending crashworthiness of smooth-shell lattice-filled structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 171, 108800 (2022).

Tran, P. & Peng, C. Triply periodic minimal surfaces sandwich structures subjected to shock impact. J. Sandw. Struct. Mater. 23, 2146–2175 (2021).

Peng, X. et al. Elastic response of anisotropic gyroid cellular structures under compression: parametric analysis. Mater. Des. 205, 109706 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Restrepo, D., Velay-Lizancos, M., Mankame, N. D. & Zavattieri, P. D. Energy dissipation in functionally two-dimensional phase-transforming cellular materials. Sci. Rep. 9, 12581 (2019).

Yang, H. & Ma, L. 1d to 3d multi-stable architected materials with zero Poisson’s ratio and controllable thermal expansion. Mater. Des. 188, 108430 (2020).

Abu-Mualla, M. & Huang, J. A dataset generation framework for symmetry-induced mechanical metamaterials. J. Mech. Des. 147, 041705 (2024).

Zheng, L., Karapiperis, K., Kumar, S. & Kochmann, D. M. Unifying the design space and optimizing linear and nonlinear truss metamaterials by generative modeling. Nat. Commun. 14, 7563 (2023).

Chen, D., Skouras, M., Zhu, B. & Matusik, W. Computational discovery of extremal microstructure families. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao7005 (2018).

Bastek, J.-H., Kumar, S., Telgen, B., Glaesener, R. N. & Kochmann, D. M. Inverting the structure-property map of truss metamaterials by deep learning. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 119, e2111505119 (2022).

Kim, N., Lee, D., Kim, C., Lee, D. & Hong, Y. Simple arithmetic operation in latent space can generate a novel three-dimensional graph metamaterials. npj Comput. Mater. 10, 236 (2024).

Makatura, L. et al. Procedural metamaterials: a unified procedural graph for metamaterial design. ACM Trans. Graph. 42, https://doi.org/10.1145/3605389 (2023).

Ha, C. S. et al. Rapid inverse design of metamaterials based on prescribed mechanical behavior through machine learning. Nat. Commun. 14, 5765 (2023).

Regenwetter, L., Nobari, A. H. & Ahmed, F. Deep generative models in engineering design: a review. J. Mech. Des. 144, 071704 (2022).

Jia, Z., Gong, H., Liu, S., Zhang, J. & Zhang, Q. Designing three-dimensional lattice structures with anticipated properties through a deep learning method. Mater. Des. 244, 113139 (2024).

Maurizi, M. et al. Inverse designing metamaterials with programmable nonlinear functional responses in graph space. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2408.06300 (2024).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Variational graph auto-encoders. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1611.07308 (2016).

Panetta, J. et al. Elastic textures for additive fabrication. ACM Trans. Graph. 34, 135–1 (2015).

Yang, Y. et al. Guided diffusion for fast inverse design of density-based mechanical metamaterials. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2401.13570 (2024).

Jiang, B. et al. Gnns for mechanical properties prediction of strut-based lattice structures. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 269, 109082 (2024).

Xiao, L., Shi, G. & Song, W. Machine learning predictions on the compressive stress-strain response of lattice-based metamaterials. Int. J. Solids Struct. 300, 112893 (2024).

Ross, E. & Hambleton, D. Using graph neural networks to approximate mechanical response on 3d lattice structures. Proc. AAG2020-Adv. Archit. Geom. 24, 466–485 (2021).

Chou, Y.-T. et al. Structgnn: An efficient graph neural network framework for static structural analysis. Comput. Struct. 299, 107385 (2024).

Jain, A., Haghighat, E. & Nelaturi, S. Latticegraphnet: a two-scale graph neural operator for simulating lattice structures. Eng. Comput. 1–16 (2024).

Abu-Mualla, M. & Huang, J. Inverse design of 3d cellular materials with physics-guided machine learning. Mater. Des. 232, 112103 (2023).

Kingma, D. P. Auto-encoding variationalBayes. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1312.6114 (2013).

Goodfellow, I. et al. Generative adversarial networks. Commun. ACM 63, 139–144 (2020).

Dos Reis, F. & Karathanasopoulos, N. Deep learning, deconvolutional neural network inverse design of strut-based lattice metamaterials. Comput. Mater. Sci. 244, 113258 (2024).

Zhang, Z., Li, M. & Yu, J. On the convergence and mode collapse of GAN. In SIGGRAPH Asia 2018 Technical Briefs, SA’18 https://doi.org/10.1145/3283254.3283282 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2018).

Dang, H., Huu, T. T., Nguyen, T. M. & Ho, N. Beyond vanilla variational autoencoders: detecting posterior collapse in conditional and hierarchical variational autoencoders. In Proc. Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations. https://openreview.net/forum?id=4zZFGliCl9 (2024).

Bastek, J.-H. & Kochmann, D. M. Inverse design of nonlinear mechanical metamaterials via video denoising diffusion models. Nat. Mach. Intell. 5, 1466–1475 (2023).

Vlassis, N. N. & Sun, W. Denoising diffusion algorithm for inverse design of microstructures with fine-tuned nonlinear material properties. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 413, 116126 (2023).

Cowin, S. C. Continuum Mechanics of Anisotropic Materials (Springer Science & Business Media, 2013).

Rahmanović, E. & Petrun, M. Analysis of higher-order bézier curves for approximation of the static magnetic properties of non-electrical steels. Mathematics 12, 445 (2024).

Bézier, P. The Mathematical Basis of the UNIURF CAD System (Butterworth-Heinemann, 2014).

Baydas, S. & Karakas, B. Defining a curve as a bezier curve. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. 13, 522–528 (2019).

Coskun, O. & Turkmen, H. S. Multi-objective optimization of variable stiffness laminated plates modeled using bézier curves. Compos. Struct. 279, 114814 (2022).

Qi, X. A review: random walk in graph sampling. arXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2209.13103 (2022).

Erdös, P., & Rényi, A. On random graphs I. Publ. Math. Debrecen 6, 18 (1959).

Dong, G., Tang, Y. & Zhao, Y. F. A 149 line homogenization code for three-dimensional cellular materials written in MATLAB. J. Eng. Mater. Tech. 141, 011005 (2018).

Maas, S. A., Ellis, B. J., Ateshian, G. A. & Weiss, J. A. Febio: finite elements for biomechanics. J. Biomech. Eng. 134, 011005 (2012).

Meyers, M. A. & Chawla, K. K. Mechanical Behavior of Materials 2nd edn (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Kipf, T. N. & Welling, M. Variational graph auto-encoders. arxiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1611.07308 (2016).

Lerique, S., Abitbol, J. L. & Karsai, M. Joint embedding of structure and features via graph convolutional networks. Appl. Netw. Sci. 5, 1–24 (2020).

Sun, Y. & Li, Q. Dynamic compressive behaviour of cellular materials: a review of phenomenon, mechanism and modelling. Int. J. Impact Eng. 112, 74–115 (2018).

Rombach, R., Blattmann, A., Lorenz, D., Esser, P. & Ommer, B. High-resolution image synthesis with latent diffusion models. In Proc. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 10684–10695 (IEEE, 2022).

Evdaimon, I. et al. Neural graph generator: feature-conditioned graph generation using latent diffusion models. arXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2403.01535 (2024).

Abu-Mualla, M., Crabtree, E., Michael, F., Pan, Y. & Huang, J. Inverse design of alloys via generative algorithms: optimization and diffusion within learned latent space. Adv. Intell. Discov. https://doi.org/10.1002/aidi.202500069 (2025).

Ho, J., Jain, A. & Abbeel, P. Denoising diffusion probabilistic models. In Larochelle, H., Ranzato, M., Hadsell, R., Balcan, M. & Lin, H. (eds.) Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, 6840–6851 (2020).

Ramdas, A., Trillos, N. G. & Cuturi, M. On Wasserstein two-sample testing and related families of nonparametric tests. Entropy 19. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19020047 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) through award CMMI-2245298 and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) through 80NSSC24M0176.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.: Methodology, Coding, Data Curation, Visualization, Writing—Original Draft. J.H.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing—Review & Editing, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Abu-Mualla, M., Huang, J. Inverse design of curved mechanical metamaterials with geometric AI: a generative diffusion operates in compact latent space of cellular structures. npj Metamaterials 1, 5 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44455-025-00005-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44455-025-00005-6