Abstract

Water stress, driven by growing human water demand and climate change, affects human well-being, depletes groundwater, and threatens the health of downstream ecosystems. Mitigating these impacts requires a clear understanding of the complex interplay of human-water-climate dynamics. Here, we present an integrated system approach to assess water stress in the severely water-stressed Yellow River Basin, covering the past 40 years and projecting scenarios until 2100. Our findings reveal extreme water stress in the basin during the 1980s–2000s, which later eased to severe levels due to improved water efficiency. However, severe water stress is not expected to be relieved before 2045 under our scenario analysis. Even under the most sustainable scenario, human water demand could exceed the severe water stress threshold by 22% (ranging from 6% to 40%) in 2100. Cross-system transformations, including enhanced water efficiency and sustainable agricultural practices, remain essential to reducing water stress in the basin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Water stress is one of the defining challenges of human society in the 21st century, highlighting the urgent need for transformative actions1,2. This condition signifies a mismatch between supply and demand, leading to inadequate access to safe water (SDG 6) or compromising ecosystem needs (SDG 15)3. Over half of the global population still lives in highly water-stressed regions4,5, especially water withdrawals exceeding 80% of water availability in the Indus and Yellow Rivers6. This scarcity markedly contributes to groundwater depletion7 and threatens the health of vulnerable downstream ecosystems8. Future water stress, driven by growing human water demand and climate change amplifies its impacts on human well-being and ecosystem stability8,9. Therefore, clarifying the underlying mechanisms of water stress and forecasting future water stress is essential for identifying potential transformative solutions for both human and ecosystem needs10,11.

Intricate mechanisms embedded in water stress are deeply interconnected with broader societal structures, energy and food systems, and climate systems12. Future global warming and land-use dynamics are disrupting precipitation and evapotranspiration patterns13, threatening the reliable water supply. The increasing human water demand14,15, driven by population growth16, accelerating urbanization17,18, growing energy demand19, and dietary shift towards more calories20, aggravates the water stress. Prior water stress projections have helped policymakers grasp future action directions but overlooked these underlying human-water-climate interactions and uncertainties21,22 from technological developments23, policies, management practices24, and socioeconomic evolution25. This leads to a long-term overreliance on a single policy lever, resulting in unintended consequences26, such as the irrigation efficiency paradox27. Recent advances in exploratory modeling have expanded our understanding of a set of plausible policy scenarios28,29. However, relying on a limited set of global narratives may overlook the fact that specific human-water-climate dynamics are crucial in some regions but less so in others25. For instance, water-stressed river basins, which are highly vulnerable to hydro-climatic fluctuations, support around 1.2 billion people and contribute to 12% of global food production and 6% of global GDP30. Yet, there is still a shortage of models that integrate complex feedbacks and region-specific assumptions for these basins. Achieving sustainable and equitable development requires a shift away from seeking a “silver bullet” solutions31, instead focusing on models that elucidate the interconnected human-water-climate processes and account for uncertainties in potential future scenarios, particularly for highly water-stressed regions32.

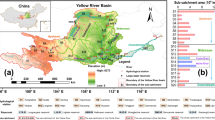

To address these gaps, we propose an integrated socio-ecohydrological system approach (ISEHSD, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2) based on exploratory modeling to understand the multi-system dynamic interlinkages. We selected the Yellow River Basin (YRB) in northern China as the study area (Supplementary Fig. 3), as it was once the most severely water-stressed river with an intertwined human-water-climate nexus. The YRB supports 12% of the nation’s population and 15% of its cultivated land with merely 2% of China’s total runoff. Severe water stress and drying-up events started in 1972 and worsened in the 1990s, lasting over 200 days in 199733. This period witnessed rapid urbanization and economic development in the basin, accompanied by a substantial increase in food and energy demand. These factors thus have driven extreme growth of agricultural and industrial water demand34, adding extreme pressures on local water resources. Given that the YRB is projected to continue facing complex challenges from climate change and socio-economic transition in the coming decades35, ISEHSD serves as a valuable tool to quantify water stress based on complex interactions and potential transformative actions of water-centric system dynamics. The approach can also be applied to other severely water-stressed big river basins to address human-nature feedback gaps and support local policy making in coping with sustainable challenges.

Water stress in the YRB is assessed using ISEHSD, with historical trend analysis from 1980 to 2020 and future scenario analysis based on localized and tailored SSP-RCP (tSSP-RCPs) pathways up to 2100. These tailored SSP-RCP pathways (see “Methods” and Table 1) combine transformative drivers. We aim to address three questions. Firstly, what underlying human-water-climate mechanisms drive the changes in water stress in the YRB? Secondly, what are the future water stress trajectories with future uncertainties? Thirdly, considering the compound effects of multi-system dynamic interactions and actions, which systemic transformations and specific measures will effectively alleviate water stress in the future? Decomposition analysis of the Water Scarcity Index (WSI, the ratio of water withdrawal and water availability, see “Methods”) revealed that the main drivers in alleviating water stress were improvements in irrigation and industrial water use efficiency. Then, we integrated these key drivers into future pathway design. Our projections show that a turning point in water stress—shifting from an increasing to a declining trend—could happen around 2045. However, even under the most sustainable setting, water stress is expected to remain high and exceed the global severe water stress threshold (WSI = 0.436) by 2100. Lastly, we identified the beneficial transformative actions, including enhanced water efficiency and sustainable agricultural practices, for alleviating water stress in the short- and long-term future.

Results

Relieved water stress by enhancing efficiency since 2000s

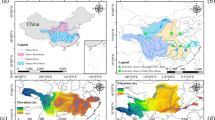

YRB’s water stress was particularly extreme around the 2000s, primarily driven by the expansion of human water demand (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). In this study, we use water scarcity index (WSI, the ratio of water withdrawal to water availability21,22, see “Methods” and Supplementary Method 1 and Table 1) to represent water stress, which is categorized into four levels as no stress (WSI < 0.2), moderate (0.2 ≤ WSI < 0.4), severe (0.4 ≤ WSI < 1), and extreme stress (1 ≤ WSI), respectively. The sharp decrease in water stress from 1997 to 2003 is notable, aligning with the shift in human water demand (Fig. 1b). Agricultural water demand took the largest share in the total human water demand, ranging from 64% to 81% during the study period. Industrial and domestic water demand shared 11% ~ 16% and 5% ~ 14%, respectively, in the total water demand, and ecological demand took the rest share. Human water demand increased from 58 km3 yr−1 in 1980 to 67 km3 yr−1 in 2020, peaking at 73 km3 yr−1 in 1997. This increase witnessed a rapid growth trajectory (1 km3 yr−2) before 1997 (P1), followed by a sharp decline (−0.7 km3 yr−2) from 1997 to 2004 (P2), and relative stability with a slight decline (−0.02 km3 yr−2) from 2004 onward (P3). This shift is likely associated with changes in the dominant sectors, that is, the agricultural and industrial activities. Water demand of both sectors declined substantially in P2 (−1.1 km3 yr−2 and −0.13 km3 yr−2, respectively) and P3 (−0.4 km3 yr−2 and −0.05 km3 yr−2, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 4c, d). Despite persistent water stress hotspots located in the LZ–TDG irrigation district and downstream regions (Fig. 1c), reduced human water demand alleviated water stress in P3 (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Water scarcity index (WSI) and trend (P < 0.001) in the YRB. The red shading indicates extreme water stress, while the gray shading indicates severe water stress. b Profile and turning point (P < 0.01) of human water demand in the YRB. Human water demand includes water withdrawal for irrigation and other agricultural activities (including grazing, forestry, and fisheries), industry production, domestic water demand (household use and service activities), and ecological water demand. The accounting process is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. Gray circles indicate turning points, and the solid line denotes the trend. c Water stress hotspots of YRB, calculated as the mean WSI for each period: P1 (1980–1996), P2 (1997–2004), and P3 (2005–2020). TNH = Tangnaihai (defined as the boundary between the source region and the upstream); LZ = Lanzhou; TDG = Toudaoguai (between the upper and midstream); HYK = Huayuankou (between the midstream and downstream); LJ = Lijin (estuary station). d Drivers of WSI. We decompose the trend and fluctuation components of the WSI using Seasonal and Trend decomposition with Loess (STL). We then analyze the Pearson correlation before and after the turning point in 1997. Colors represent the magnitude of the correlation coefficients. ** denotes a significance level of P < 0.01, while * indicates P < 0.05.

Decomposition analysis (see “Methods”) of the WSI revealed that the main drivers in alleviating water stress were improvements in irrigation and industrial water use efficiency and increasing precipitation (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Figs. 4a and 5). Human water demand is decomposed into twelve socio-economic drivers (Supplementary Table 1) while water availability is decomposed into precipitation effect and water yield capacity effect (Eq. 9). Before the turning point in 1997, the growing scale of socioeconomic indicators, such as population, gross value added (GVA), crop production, and meat production, positively influenced the increasing WSI trend. In contrast, water use efficiency (water use per product or capita, hereafter WUE) indicators showed a negative impact on the WSI. Especially for irrigation WUE, it offsets 26% of the total increase in human water demand (Supplementary Fig. 4e). However, the rebound effect of irrigation in the midstream and downstream regions was evident in P1 (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). Industrial WUE had the opposite effect, slowing the growth of human water demand by 9%, particularly in regions like Inner Mongolia (Supplementary Fig. 8). After 1997, WUE improvements showed a significantly positive impact on the decreasing WSI trend, particularly in irrigation and industry. The water demand reduction due to WUE improvements during P2—25% for irrigation and 22% for the industry—offset the positive effects of growing socioeconomic scale indicators, especially in downstream regions like Shandong (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10). In P3, the continuing improvement in irrigation and industrial WUE contributed to a significant restriction on water demand, leading to overall reductions of 28.1% and 15.7%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4e).

Future water stress and human water demand

Human water demand in the YRB is projected to undergo significant transitions between the 2030 s and 2050 s, with varying trends and turning points across all scenarios (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 11a, b). Under the Business-as-Usual (BAU) scenario (see “Methods”, Table 1 and Supplementary Method 2), human water demand would peak at 74 ± 3 km3 yr−1 in 2043, increasing by a rate of 0.2 ± 0.1 km3 yr−2 after 2020, and decline at a rate of −0.5 ± 0.2 km3 yr−2 thereafter. In the tSSP1-RCP2.6 scenario, representing the most sustainable future in our analysis, human water demand continuously decreases across most of the alternative states of the world (SOWs, 74%) (Supplementary Fig. 11a). These SOWs represent plausible combinations of demographic, technological, and policy-related factors. In contrast, under the tSSP5-RCP8.5 scenario, the worst sustainable future, demand increases rapidly across all SOWs, with peak demand delayed until 2046. Compared to BAU, tSSP1-RCP2.6 could reduce human water demand by 6% (ranging from 4% to 9%) by 2040, whereas tSSP5-RCP8.5 could increase it by 33% (ranging from 22% to 54%) by 2046. Regarding water supply (Fig. 2b), the combined effects of precipitation, evapotranspiration, underlying surface patterns and ecological water restriction, as embedded in our models, lead to specific outcomes for water availability for humans across scenarios (Supplementary Eqs. S26 to S29). tSSP5-RCP8.5 shows higher initial water availability due to increased precipitation before the 2050 s, but experiences sharp declines driven by rising evapotranspiration and reduced water yield capacity (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b), further intensified by uneven precipitation distribution that degrades soil infiltration and reshapes subsurface dynamics. Relaxed water restrictions further reduce ecological water allocation. In contrast, tSSP1-RCP2.6 maintains stable water resources through balanced evapotranspiration and precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d), ensuring sufficient human water availability alongside ecological conservation. tSSP2-RCP4.5 sees an overall increase in water availability for humans, as rising precipitation offsets moderate evapotranspiration (Supplementary Fig. 12e, f), with limited water restrictions allowing for sustainable human use.

a Future projection for human water demand under the business-as-usual (BAU) and three tSSP-RCPs scenarios. Years marked with circles during the historical period are related to demand-side management strategies (details see Supplementary Fig. 13). Years marked with circles during the future period indicate significant turning points. b, c Future projection for water availability for humans and WSI under different scenarios in the YRB. Shading indicates the uncertainty across all simulation experiments within each scenario. In all panels, darker bands represent ±1 standard deviation around the mean, while lighter bands show the uncertainty range based on the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles. Solid colored lines denote the mean value, and dashed lines indicate the 10-year moving average. Red shading denotes values exceeding the severe threshold.

The WSI is jointly influenced by human water demand and supply, resulting in increased scenario variability and heightened sensitivity to hydro-climatic changes. Notably, 94% of SOWs exhibit a declining trend after 2045 (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 11c, d). In both the BAU and tSSP2-RCP4.5 scenarios, WSI shows a downward trend around 2030 but remains above the severe stress threshold by 19% (ranging from 12 to 26%) by 2100. The wide distribution of turning points (Supplementary Fig. 11d) indicates structural vulnerability to imbalances between supply and demand in the absence of effective management. The tSSP5-RCP8.5 scenario leads to extreme water stress, with WSI surpassing 1 before 2056 (Fig. 2c). Importantly, the WSI turning points occur ahead of HWD across these scenarios, suggesting that changes in water availability trigger WSI responses earlier than human adaptation measures.

In contrast, the tSSP1-RCP2.6 scenario, representing the most sustainable future alternative, with 60% of SOWs showing a continuous declining trend in WSI, while 22% experience a decline after 2040, indicating that early-stage governance effectively mitigates water stress. However, rebounds may still occur in a limited number of SOWs due to constraints in water yield and radical ecological flow management. Even under this most sustainable future, the WSI remains 22% (ranging from 16% to 28%) above the severe stress threshold (WSI = 0.4) by 2100.

To further investigate the impacts of future human water demand, precipitation, and water yield capacity, we decompose WSI into these three driving factors (Eq. 9 and Supplementary Fig. 14). Under tSSP1-RCP2.6, increasing precipitation plays a key role in relieving water stress before 2030. After that, the decline in human water demand contributes substantially to alleviating stress. In the tSSP2-RCP4.5 and BAU, the impact of stable human water demand on reducing stress is less pronounced compared to fluctuating precipitation and the proportion of water allocated to human use. The offset effects of precipitation and water yield capacity become more pronounced after 2040, suggesting that alleviating water stress may increasingly depend on favorable water supply conditions in the future. Under tSSP5-RCP8.5, the increase of precipitation and water yield capacity prior to 2050 appears insufficient to offset the growing human water demand, and they fail to relieve water stress. In fact, the declining water yield capacity exacerbates the stress, signaling a looming crisis where ecosystem demands are likely to surpass human water demand, further intensifying competition for water resources.

Key transformative factors and interactions for relieving water stress

Key system transformations across pathways and sectors provide valuable insights for demand-side strategies, with variable changes in the comparison between tSSP1-RCP2.6 and BAU demonstrating the positive impact of effective demand management. Fluctuations in future climate conditions would cause variability in crop yields. Crop production is expected to decrease by 6% in tSSP1-RCP2.6 compared to the BAU scenario by 2040 due to shrinking cropland, reducing irrigational water demand (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 15). Improvements in irrigation efficiency under tSSP1-RCP2.6 could further accelerate this decline. Another factor is the shift towards more sustainable diets, particularly in the tSSP1-RCP2.6 scenario, where a declining population could reduce meat production by 55%. Together, these factors contribute to a 7% reduction in total agricultural water demand compared to the BAU scenario. Population changes, driven by fertility patterns, birth gender, life expectancy, and economic development, vary across scenarios, with reductions ranging from 4% to 6% compared to 2020 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Societal drivers in education, employment, and technological innovation are expected to increase per capita Gross Value Added (GVA), improving water use efficiency across sectors and reducing energy demand. Water-related energy demand is projected to decrease by 41% (ranging from 39% to 46%) in tSSP1-RCP2.6 compared to BAU by 2040. The transition to renewable energy sources, alongside related action plans, will reduce water demand in energy production. These combined factors contribute to a 13% reduction in industrial water demand (ranging from 9% to 21%) compared to the BAU scenario by 2040.

The first column shows the model’s system transformation output, categorizing the influential parameters in the following sensitive analysis (see Fig. 4) and associated with the qualitative system changes (indicated by the black bold block of text) and the sectors (indicated by the gray bold block of text). Green upward triangles represent the increase or enhancement compared with BAU, yellow downward triangles represent the decline or mitigation compared with BAU, gray horizontal lines represent the interactions with no change or follow the historical trend and blue wavy lines represent fluctuations or uncertain trends.

Sensitivity analysis provides a more intuitive understanding of future cross-system dynamic interactions and water stress before the turning point in 2050 (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 16–18). Economic, technological, and energy parameters are the most influential. The elasticities of energy, industrial, and domestic water demand in response to economic indicators are particularly sensitive, highlighting water and energy sectors’ feedback on potential further improvements in water and energy efficiency (Supplementary Eqs. S23, S25, S34, and S35). Capital elasticities and innovation are of secondary importance, highlighting economic-technical feedback in shaping sustainable water management (Supplementary Eqs. S9–S16). In contrast, agricultural investment shows a more limited long-term impact on water resources, with growth being less influenced by temporal scale, indicating that future structural adjustments, such as optimizing crop patterns and reducing the cultivation of water-intensive crops, could alleviate pressure on water resources, particularly under water scarcity constraints. Human well-being parameters, including fertility, labor, and education, show slight sensitivity to water stress in the future (Supplementary Eqs. S2–S8). Environment and natural resource parameters and ecological flow management variables are more sensitive in the WSI, looming the importance of balancing human and ecosystem needs in water allocation (Supplementary Eq. S29). Vegetation is less responsive to changes in WSI, further emphasizing the potential for demand-side mitigation (Supplementary Eq. S28).

The normalized Morris index values (μ*) are determined by determining sensitivity between 0 and 1. The sensitivity analysis investigated the effect of 24 input parameters (columns) on six output variables (rows). The colors in the grid cells represent the total sensitivity effects, while the numbers describe the rankings of parameter influence. Elasticities of water and energy demand in our model are defined as the relative change in one variable caused by a change in another variable, and the larger the elasticity, the more sensitive the variable is to changes. Original values of μ* with confidence intervals are shown in Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17.

Discussion

This paper presents an integrated analysis of water stress in the YRB over the past 40 years and projects future trends under localized and tailored scenarios up to 2100. The analysis evaluates potential transformative management strategies and the uncertainties involved. Observed water stress was particularly extreme around the 2000s, followed by a period of alleviation, consistent with patterns in water demand curves (Fig. 5)37,38,39,40. These patterns suggest that human water demand has an upper limit, constrained by both water availability and management capacities41. However, the double lag phenomenon observed in the YRB was identified in the 2000s due to delayed water restriction policies following frequent drying-up33 (Fig. 1), and it reoccurs in the 2040 s (Fig. 2). These reflect systematic path dependence and call for adaptive water management.

Expanding economic activities in P1 (Stage 2) could increase human water demand, while the rebound effects of irrigation and industry WUE contributed to additional water demand. In P2 (Stage 3), demand mitigation from WUE driven by moderate water restrictions and efficiency strategies became more prominent, surpassing the demand growth from socio-economic scale factors (detailed policies in Supplementary Fig. 13)40. In recent years (Stage 4), the driving factors from the dual influences have become more diverse. Emerging ecological water demand and industrial structure shifts introduced changes in the water demand curve37. Our projections and results provided cross-system options and pathways for Stage 5.

Since the 1980s, extensive human-induced modifications in the midstream and downstream regions—such as large-scale irrigation42, dam-induced alterations to river morphology43, and increased competition for water among stakeholders44—have collectively reshaped hydrological connectivity and flow regimes34. These changes culminated in drying up of the main channel near its mouth (as recorded at LJ) for 226 days in 199733. The event coincided with peak WSI levels, downstream stress hotspots, and the irrigation rebound effects we observed (Fig. 1b, c, P1 in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7).

After the 2000s, human management interventions, such as the annual water allocation scheme introduced in 199845 and the unified water regulations implemented in 2002, have alleviated water stress. This relief is primarily attributable to improvements in the downstream regions (Fig. 1b, c). These findings suggest that the “efficiency paradox”27 in the YRB may be gradually dissipating. Our decomposition analysis may support this hypothesis, showing improvements in the upper and downstream regions around the 2000s (P2 in Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), likely driven by enhanced socio-technical adaptability.

Future challenges remain deeply uncertain, driven by both supply-side fluctuations and evolving demand pressures. While limited improvements in water yield capacity have been observed, adverse hydrological impacts have become more pronounced since the 2000s, intensifying under the tSSP5-RCP8.5 scenario, especially in upstream regions (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Fig. 12a, b). Even under the most sustainable scenario (tSSP1-RCP2.6), which aligns with other global hydrological model (GHM) projections, water stress in the YRB is expected to remain high through 2100, with potential increases in water demand still possible by 2050 (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20). This may come at the cost of water storage loss46. Ultimately, relief from water stress is expected to depend heavily on increased precipitation (Supplementary Fig. 14). Given the limited ability to control future climate uncertainty, semi-arid river basins like the YRB, with dense populations and high sensitivity to hydro-climatic variability, will require cross-system transformations and interdisciplinary approaches to effectively address sustainable challenges45.

Relieving water stress in the most sustainable future scenario (tSSP1-RCP2.6) underscores the need for cross-system collaboration and transformation in governing severely water-stressed rivers in the future47. In the YRB, the elasticities of energy and industrial water demand in relation to economic indicators, as reflected in the persistent effects in 2030 and 2050 (Fig. 4), reveal the critical role of the interrelationship between water-use sectors and the economy, technology, and energy sectors in mitigating water stress. These factors are closely linked to a region’s economic structure, technological advancement, policy intervention, and pricing mechanisms. Several transformative strategies demonstrate the potential and priority of coordinated sectoral actions to mitigate future water stress (Figs. 3 and 4, Table 2). These include sustainable agricultural practices (e.g., more technology-driven agricultural production), renewable energy initiatives (e.g., incentives for renewable energy development), healthier dietary and ecological water management (e.g., justified ecological flow thresholds). Similar findings are observed in other highly water-stressed basins, including the prioritization of ecological water flows and technological advances in the Heihe River48 and the water-energy-food nexus in the Nile49 and Indus River50. Collectively, these interventions go beyond the conventional water sector, forming an integrated response framework that spans food, energy, and other human systems. However, such comprehensive improvements under the tSSP1-RCP2.6 scenario remain an idealized assumption, as real-world actions tend to be fragmented, addressing one sector or solution at a time51.

Cooperative efforts from stakeholders across the basin are crucial but challenging, as variations in natural and socio-economic conditions across sub-basins and administrative units complicate collaboration (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 21). In the YRB, runoff above TNH is critical in sustaining socio-economic development and food production in the downstream regions. Although recent improvements in water availability have been observed, the upstream remains highly vulnerable to climate change. Our scenario analysis reveals divergent projections of water yield capacity, with severe declines in the upstream region under the tSSP5-RCP8.5 scenario in the late 21st century (Supplementary Fig. 12). This highlights the risk of over-reliance on glacier and snowmelt resources and emphasizes the urgency of mitigating warming trends and conserving upstream ecosystems52,53. To address these risks, actionable measures include conserving alpine ecosystems and implementing ecological compensation programs to support sustainable water supply in the upstream regions.

Persistent water stress in the LZ-TDG reaches, as well as downstream of HYK, further reveals structural vulnerabilities (Fig. 2c). Large-scale irrigation in these regions and ecological restoration in the midstream increased evapotranspiration and is expected to intensify in the future10, exacerbating competition for water across sectors (Supplementary Fig. 12). In the LZ-TDG reach, which has long been a key area of agricultural water consumption, sustained water stress demands targeted interventions (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 21). The rebound effect observed in P3 indicates that optimizing crop patterns and promoting standardized production remain necessary (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7). In the downstream region of HYK, a densely populated and economically active area (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 10), adaptive water allocation mechanisms should be established to balance sectoral water demands. In the midstream, where extensive ecological restorations are underway, it is crucial to align restoration efforts with the region’s water carrying capacity. Implementing unified water accounting and interdisciplinary frameworks is recommended to prevent unintended increases in evapotranspiration while achieving ecological goals, thereby avoiding further stress on the basin’s water resources (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Transformative actions for mitigating water stress under deep uncertainties make long-term projections particularly challenging, especially in basins with complex human governance. The ISEHSD framework we proposed incorporates tailored technological assumptions, policy responses, and cross-system dynamics to capture realistic system behaviors and feedbacks (Supplementary Method 2). Focusing on “what-if” projections, our results show that extreme scenario designs—such as the worst-case (tSSP5-RCP8.5) and the most sustainable future (tSSP1-RCP2.6)—often produce unexpected or mixed outcomes compared to GHMs (Supplementary Figs. 11 and 20, detailed in Supplementary Discussion 1). This underscores the importance of specific basin-scale, exploratory modeling in highly uncertain domains, as well as the limitations of relying solely on a narrow set of global narratives or single-strategy assumptions.

Despite ongoing integrated modeling efforts in water-stressed basins, barriers remain in capturing dynamic interactions. Temporal dynamic parameters in our sensitivity analysis highlight key cross-system mechanisms, helping us identify priority sectors (Fig. 3), interactions (Fig. 4), and transformative actions (Table 2) for regions experiencing severe water stress. Our model provides a practical and transferable framework that prioritizes interdisciplinary structures and feedbacks, while incorporating localized future scenarios. Through calibration and customization, this framework can be adapted to other highly water-stressed basins beyond the YRB such as the Indus and Nile, supporting a sustainable transition to addressing water crisis.

Although our results align broadly with comparable projection simulations and historical trends (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 22), our scenarios incorporate a wide range of uncertainties (Supplementary Discussion 2), with many future planning inputs cross-validating against local reports. However, parameter uncertainties propagated as inter-module interactions intensified (Supplementary Discussion 3). Exogenous uncertainties in the WSI may arise from historical data. Given barriers to open-access human water data54, we rely on data from Water Resources Bulletins. A quality control procedure is implemented to ensure a robust and long-term dataset (Supplementary Method 3). However, sub-provincial heterogeneity still affected results. Future work will focus on incorporating finer-scale modeling (e.g., at the prefecture level) supported by high-resolution data.

In summary, our results demonstrate that even under the most optimistic compound implications, future high water stress remains in the YRB. Cross-system transformative actions are essential to mitigate water stress before 2050. By quantifying these actions’ cascade and compound effects on water stress and multi-system dynamic interactions within our ISHESD framework, we found that mitigating future water stress will benefit from enhanced energy and water efficiency, promote sustainable agricultural practices, healthier diet, and accelerate the adoption of renewable energy sources. For severe water stress basins with multi-system feedback and trade-offs among stakeholders, elucidating these long-term dynamic interconnections and compound effects within our framework is crucial for formulating more robust strategies for sustainable water management and resilience across diverse climatic, ecological, and socio-economic contexts.

Methods

Assessing water stress

Water stress is assessed by the Water Scarcity Index (WSI)21,22.

where WSI is categorized as follows: minimal (WSI < 0.2), moderate (0.2 ≤ WSI < 0.4), severe (0.4 ≤ WSI < 1), and extreme (WSI ≥ 1)6,13. HWD represents human water demand, which decomposed into irrigation and other agricultural activities (including grazing, forestry, and fisheries), industrial water demand (industry and construction), domestic water demand (urban and rural household use and service activities), ecological water demand (ecological and environmental activities, e.g., built-up area greening). We calculate the human water demand with the water balance equation (Supplementary Table 1) employing the accounting process in Supplementary Fig. 2. WA stands for water availability for humans, calculated from water yield and ecological flows45.

Trend and decomposition analysis

A linear regression model is used to estimate trends in human water demand for both historical and future periods (see Supplementary Method 1). The trend is determined by calculating the slope of the regression line fitted to the time series data using the least squares method. The turning point of the system state is defined as the trend shift. For validation, trend analysis for the future period is conducted through 2000 simulation runs based on our projection experiment. Additionally, Seasonal and Trend decomposition using Loess (STL) and correlation analysis are employed to identify significant trends and fluctuations related to changes in water stress. These indicators are integrated into the model prior to construction.

Human water demand is decomposed into twelve socio-economic drivers (Supplementary Table 1), distinguished as water use efficiency (WUE) and sectorial socio-economic scale effects (Eqs. 2–8, results presented in Supplementary Figs. 4, 8–10).

where, ΔHWDscale and ΔHWDefficiency stands for social-economic scale effect and water use efficiency effect. i represents human water use sectors. t and t1 represent the interval-period from trend analysis. Si and WUEi represent the social-economic scale and efficiency indicators in Supplementary Table 1.

We assess the contributions of precipitation, water yield capacity (the ratio of runoff to precipitation), and HWD to the relative rate of change in water stress in the YRB (Eqs. 9–15, results presented in Supplementary Figs. 4, 5 and 14).

where, ΔWSIHWD, ΔWSIP and ΔWSIWA/P stands for the contributions of human water demand, precipitation effect and water yield capacity effect, respectively. Taking the natural logarithm of both sides and differencing between time steps t−1 and t yields a decomposition of the WSI change into three additive logarithmic terms, as shown in Eq. 10. This total change is then represented as the sum of the individual contributions from each factor (Eq. 11). To ensure consistency and avoid residuals, we use a logarithmic mean weight L(WSIt), defined in Eq. 12, which is then used to compute the contribution of each component by multiplying it with the log-change of the corresponding variable (Eqs. 13–15).

The interpretation of positive and negative values in the decomposition of the WSI provides important insights into the factors influencing water stress. A positive value for ΔWSIHWD indicates that increased water demand exacerbates water stress, while a negative value suggests that reduced water demand helps alleviate water stress. For the contribution of ΔWSIP, a positive value implies that reduced precipitation exacerbates water stress by decreasing water availability, whereas a negative value shows that increased precipitation improves water availability, thereby reducing water stress. Similarly, for the ΔWSIWA/P, a positive value reflects a decline in water yield capacity, leading to heightened water stress, while a negative value indicates that improved water yield capacity helps mitigate water stress.

Integrated socio-ecohydrological system approach (ISHESD)

We have developed and applied an integrated socio-ecohydrological system approach for large river basins (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Building upon the modules of the CHANS_YRB55 model, the ISHESD model also incorporates modules for water demand and supply, population, economy, energy, food demand, and production with options for pathway assumptions. Water yield is simulated at the sub-basin scale using the Choudhury-Yang equation (Supplementary Fig. 3a), while other modules are modeled at the provincial scale across the basin (Supplementary Fig. 3b). Well-being indicators (education, fertility, childbearing and life expectancy), along with modules for meat consumption, economy, population, energy, and sectoral water demand (including domestic and industrial needs), are localized to nine provinces based on the T21 China model56. Irrigation water demand is calculated using the Crop Water Requirement Method, accounting for irrigation efficiency57. The initial version of CHANS_YRB presented a conceptual framework to describe the dynamic interactions and feedback within the coupled human-natural system of the YRB. Building upon this foundation, we developed tSSPs through exploratory modeling to examine potential future trajectories. The improvements made to the CHANS_YRB can be categorized into three main areas:

1. Integration of Human-Water-Climate Interactions: We enhanced the model by incorporating a comprehensive representation of human-water-climate interactions, focusing on key levers for tSSPs. These cross-system links are visually depicted in Supplementary Method 2.1 and Table 2, with parameters and data sources listed in Supplementary Table 3.

2. Localization of tSSPs: We tailored the SSPs to reflect the YRB’s specific biophysical and socioeconomic conditions, with corresponding data resources tSSPs (Supplementary Method 2.3 and Table 4). These localized pathways are grounded in qualitative research, which examines local policies, reports, and academic literature to contextualize the parameters and assumptions used in the exploratory modeling process, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1.

3. Applicability Beyond the YRB: The tSSP method, while tailored to the URB, is applicable to other water-stressed basins. The modeling framework aligns with approaches used in FeliX58,59. We considered each province as a unit, with parameters (e.g. elasticities) calculated based on historical trends and set the different target levels set according to varying pathway options.

Model integration

Modeling large river basin systems requires integrating both ecological units (e.g., natural watersheds) and human governance or demand boundaries (e.g., administrative divisions), rather than relying on either alone60. To address this challenge, we developed a multi-scale modeling framework that combines sub-basin scale water yield simulations with province-scale socioeconomic modules using proportion-based proxy variables. Specifically, provincial socioeconomic variables were converted to basin-level estimates by applying historical proportions derived from prefecture-level units located within the basin boundaries of each province (see Supplementary Method 2 and Eq. S36). In the calculation of the WSI, sectoral water use was spatially downscaled based on the historical share of water use from basin-included prefectures (Eqs. S37 and S38). Similarly, basin-level population was estimated using the historical proportion of provincial population living in those areas. These proxy variables were constructed annually and used to downscale provincial data over the historical period from 1981 to 2020. Notably, the proportions remained highly stable within ±1% during the historical period, and we assume they remain stable in future scenario projections.

Although prefecture-level modeling could offer finer demand-side solutions for human governance, we adopted the compromise choice that balances provincial-level and basin-wide performance based on the following considerations. First, due to data availability, provincial-level modeling provides a broader range of representative socioeconomic variables for scenario design, enabling the consideration of complex feedback loops. In this version, we prioritize systemic interactions and scenario exploration over computational complexity. Second, from a governance perspective, YRB is the first basin in China to establish a water allocation institution44. In practice, water resource management and allocation decisions in the basin are primarily made at the basin-wide, provincial, and district levels, reflecting the roles of key stakeholders and administrative institutions.

Model validation and sensitivity analysis

The integrated model incorporates a range of socio-economic, ecological, and hydrological parameters. We conducted a global sensitivity analysis to simplify the model structure, clarify the uncertainty in the human-water system, and highlight the practical parameters for water resource management. The Morris method is used for global sensitivity analysis due to its efficiency and ability to identify and rank influential parameters with nonlinearities and interaction effects within computational constraints61. Special attention is given to uncertain parameters with high uncertainty, showing significant effects on outputs. Uncertainty bounds are defined using a random uniform distribution with a ± 15% variation around reference values.

We selected 24 input parameters for sensitivity analysis following five rules. Firstly, parameters should be related to the theme of alleviating water stress. Secondly, parameters should be diverse across population and well-being, climate change, agricultural, energy, ecological, and policy domains. Third, parameters should represent future uncertainty and actionable management options. Fourth, parameters should be supported by local policy and regional specificity to the YRB and China. Last, parameters should be practical for sensitivity analysis with robust frameworks. After addressing model flaws identified during the analysis, we perform 2000 Morris simulations to assess sensitivity, using the normalized Morris index (μ*) to rank the input parameters based on their influence on the outputs. Original μ* values and their bootstrapped confidence intervals are shown in Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17. The σ index is used to represent the degree of nonlinearity or interaction-driven variability associated with each input variable (Supplementary Fig. 18).

To accurately reflect the historical dynamics over the past 40 years and support credible future projections, we validated the model empirically through three procedures. First, we calibrated the core variables in each module using historical time series. The goodness-of-fit statistics for the simulated and actual data, where historical data is available, are presented in Supplementary Fig. 22. These statistics include Coefficient of determination (R2), Correlation Coefficient (r), Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and the Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE), all of which were used to assess model performance. Historical data were sourced from statistical records, monitoring observations, and comparable simulations from datasets and models (see Supplementary Table 5).

Second, we also reported the validation metrics separately for two periods (1981–2000 and 2001–2020) in Supplementary Figs. 23 and 24. This temporal split validation would further test the model’s robustness, particularly given the policy shifts post-2000.

Third, we compared our future projection results with those from similar studies and model outputs. Due to the limited availability of projections at the same spatial scale and under identical conditions, our comparison of key variables is restricted to the global, national, or provincial level (Supplementary Figs. 19 and 20).

Pathway projection and exploratory modeling

We proposed three localized and tailored tSSP1-RCP2.6, tSSP2-RCP4.5, and tSSP5-RCP8.5 based on current literature, regional policies, and goals for model inputs (see Fig. 3, Table 1 and Supplementary Method 2.3). Three pathways comprise 5 categories and 16 components, each consisting of one reference and 3 scenario strategies (Supplementary Table 4): Climate change (precipitation, temperature, evaporations), Human well-being (fertility, gender, employment, education and life expectancy), Economy, technology and energy transition (energy consumption, water withdrawal, technology innovation, investment, renewable energy, economic and water efficiency policy), Sustainable agricultural system and healthy nutrition (crop production, irrigation system and dietary changes), and Environment and natural resources enhancement (land use changes, vegetation changes and ecological flow management). These categories reflect core components of interdisciplinary transformative actions and are consistent with established classifications used in previous SSPs region research62,63.

The BAU scenario serves as our reference, with its climate change parameters following the tSSP2-RCP4.5 projections. Compared to BAU, tSSP1-RCP2.6 assumes enhanced socioeconomic conditions, such as lower population growth, stronger economic growth, healthier diets, and improved access to greenspace, employment, education, and fertility services. It also features a faster transition to greener technologies, with higher clean energy adoption rates, greater efficiency, and stricter water demand and investment restrictions. Additionally, it assumes the restoration of grasslands and limited expansion of croplands and urban areas. tSSP2-RCP4.5 fall between tSSP1-RCP2.6 and BAU in terms of socioeconomic and environmental changes. In contrast, tSSP5-RCP8.5 assumes a “highway” trajectory with rapid socioeconomic growth (higher economic and population growth, and increased food demand) but at the expense of unsustainable development patterns, such as a slower transition to greener technologies. This pathway follows the climate parameters set by tSSP5-RCP8.5.

The parameterization of the tSSP-RCPs was carried out using a mixed-method approach that integrated four key types of inputs: (1) Reanalysis datasets: Meteorological variables (e.g., precipitation, temperature) derived from downscaled CMIP6; (2) Historical trends: Long-term statistical records used to calculate trends at the provincial or sub-basin scale; (3) Quantitative targets and qualitative information: Data extracted from provincial development plans and regional literature since the 2010s; and (4) Qualitative scenario classifications: Scenarios based on the narrative structures of the global SSP framework. Scenario-specific assumptions adhered to the level-setting conventions of the narrative-based FeliX model, including BAU, SSP1, SSP2, and SSP558,59.

These pathway assumptions were translated into quantitative model parameters using dynamic functions, as detailed in FeliX58 and outlined in Supplementary Method 2.2. This integrated approach ensures that both qualitative and quantitative scenario assumptions are firmly grounded in observed and statistical data, contextualized by local policy frameworks, and aligned with the globally consistent logic of SSP-RCP scenarios. All data sources are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

To support decision-making under deep uncertainty, we apply Exploratory Modeling and Analysis (EMA), a computational approach designed to identify robust strategies across various possible futures64. After identifying the key influential parameters related to regional strategies and targets through sensitivity analysis, we conducted a series of model runs using Latin hypercube sampling to explore the full range of variability in pathway performance under uncertainty. Each model run was treated as an independent computational experiment, representing a distinct alternative state of the world (SOW). We systematically perturbed the selected parameters by ±15% and conducted 2000 simulations for each of the three pathways, resulting in a total of 8000 simulations.

All scenario parameters, along with their associated variables, were assumed to be independent across all SOWs, enabling a systematic exploration of the scenario input space. Nonetheless, we acknowledge that the model structure may still allow for implicit and unexpressed interactions (e.g., indirect effects of economic factors on land use transition) due to structural uncertainty. Scenario narratives (Table 1), experiment parameters (Supplementary Table 4), and their linkages with model outputs (Supplementary Table 2) are mapped to clarify the boundaries of interactions. We further performed a statistical assessment of input correlations across the SOWs, which confirmed a high level of independence among the scenario variables (Supplementary Fig. 25).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

Any further code that supports this study’s main findings is available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Rosa, L. & Sangiorgio, M. Global water gaps under future warming levels. Nat. Commun. 16, 1192 (2025).

Taka, M. et al. The potential of water security in leveraging Agenda 2030. One Earth 4, 258–268 (2021).

Grafton, R. Q. et al. Rethinking responses to the world’s water crises. Nat. Sustain. 8, 11–21 (2024).

Baccour, S. et al. Water quality management could halve future water scarcity cost-effectively in the Pearl River Basin. Nat. Commun. 15, 5669 (2024).

Hope, R. Four billion people lack safe water. Science 385, 708–709 (2024).

Greve, P. et al. Global assessment of water challenges under uncertainty in water scarcity projections. Nat. Sustain. 1, 486–494 (2018).

Long, D. et al. South-to-North Water Diversion stabilizing Beijing’s groundwater levels. Nat. Commun. 11, 3665 (2020).

Zhao, G. et al. Decoupling of surface water storage from precipitation in global drylands due to anthropogenic activity. Nat. Water 3, 80–88 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Timing the first emergence and disappearance of global water scarcity. Nat. Commun. 15, 7129 (2024).

Feng, X. et al. Revegetation in China’s Loess Plateau is approaching sustainable water resource limits. Nat. Clim. Chang. 6, 1019–1022 (2016).

UNESCO. Water for Prosperity and Peace; Facts, Figures and Action Examples. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000388952 (2024).

Qin, Y. et al. Flexibility and intensity of global water use. Nat. Sustain. 2, 515–523 (2019).

He, C. et al. Future global urban water scarcity and potential solutions. Nat. Commun. 12, 4667 (2021).

Mehta, P. et al. Half of twenty-first century global irrigation expansion has been in water-stressed regions. Nat. Water. 2, 254–261 (2024).

Kummu, M. et al. The world’s road to water scarcity: shortage and stress in the 20th century and pathways towards sustainability. Sci. Rep. 6, 38495 (2016).

Boretti, A. & Rosa, L. Reassessing the projections of the World Water Development Report. NPJ Clean Water 2, 1–6 (2019).

Flörke, M., Schneider, C. & McDonald, R. I. Water competition between cities and agriculture driven by climate change and urban growth. Nat. Sustain. 1, 51–58 (2018).

Savelli, E., Mazzoleni, M., Di Baldassarre, G., Cloke, H. & Rusca, M. Urban water crises driven by elites’ unsustainable consumption. Nat. Sustain. 6, 929–940 (2023).

Cai, J., Yin, H. & Varis, O. Impacts of industrial transition on water use intensity and energy-related carbon intensity in China: a spatio-temporal analysis during 2003–2012. Appl. Energy 183, 1112–1122 (2016).

Tuninetti, M., Ridolfi, L. & Laio, F. Compliance with EAT–Lancet dietary guidelines would reduce global water footprint but increase it for 40% of the world population. Nat. Food 3, 143–151 (2022).

Veldkamp, T. I. E. et al. Water scarcity hotspots travel downstream due to human interventions in the 20th and 21st century. Nat. Commun. 8, 15697 (2017).

Zhang, W., Liang, W., Gao, X., Li, J. & Zhao, X. Trajectory in water scarcity and potential water savings benefits in the Yellow River basin. J. Hydrol. 633, 130998 (2024).

Selin, N. E., Giang, A. & Clark, W. C. Showcasing advances and building community in modeling for sustainability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2215689121 (2024).

Kwakkel, J. H., Walker, W. E. & Haasnoot, M. Coping with the wickedness of public policy problems: approaches for decision making under deep uncertainty. J. Water Resour. Plan. Manage. -ASCE 142, 01816001 (2016).

Dolan, F. et al. Evaluating the economic impact of water scarcity in a changing world. Nat. Commun. 12, 1915 (2021).

Mijic, A., Liu, L., O’Keeffe, J., Dobson, B. & Chun, K. P. A meta-model of socio-hydrological phenomena for sustainable water management. Nat. Sustain 7, 7–14 (2024).

Grafton, R. Q. et al. The paradox of irrigation efficiency. Science 361, 748–750 (2018).

Razavi, S. et al. Convergent and transdisciplinary integration: on the future of integrated modeling of human-water systems. Water Resour. Res. 61, e2024WR038088 (2025).

Quinn, J. D., Hadjimichael, A., Reed, P. M. & Steinschneider, S. Can exploratory modeling of water scarcity vulnerabilities and robustness be scenario neutral? Earth Future 8, e2020EF001650 (2020).

Huggins, X. et al. Hotspots for social and ecological impacts from freshwater stress and storage loss. Nat. Commun. 13, 439 (2022).

Gil-García, L. et al. Actionable human–water system modelling under uncertainty. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 4501–4520 (2024).

Alizadeh, M. R., Adamowski, J. & Inam, A. Scenario analysis of local storylines to represent uncertainty in complex human-water systems. J. Hydrol. 635, 131186 (2024).

Yang, D. et al. Analysis of water resources variability in the Yellow River of China during the last half century using historical data. Water Resour. Res. 40, W06502 (2004).

Yin, Z. et al. Irrigation, damming, and streamflow fluctuations of the Yellow River. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 1133–1150 (2021).

Wu, X. et al. Ecological restoration in the Yellow River Basin enhances hydropower potential. Nat. Commun. 16, 2566 (2025).

Liu, J. et al. Water scarcity assessments in the past, present, and future. Earth Future 5, 545–559 (2017).

Liu, Y., Zheng, H. & Zhao, J. Reframing water demand management: a new co-governance framework coupling supply-side and demand-side solutions toward sustainability. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 28, 2223–2238 (2024).

Loch, A., Adamson, D. & Dumbrell, N. P. The fifth stage in water management: policy lessons for water governance. Water Resour. Res. 56, e2019WR026714 (2020).

Gleick, P. H. & Palaniappan, M. Peak water limits to freshwater withdrawal and use. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 11155–11162 (2010).

Song, S. et al. Identifying regime transitions for water governance in the Yellow River Basin, China. Water Resour. Res. 59, e2022WR033819 (2023).

Lei, X., Zhao, J., Wang, D. & Sivapalan, M. A Budyko-type model for human water consumption. J. Hydrol. 567, 212–226 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Recent anthropogenic curtailing of Yellow River runoff and sediment load is unprecedented over the past 500 y. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 18251–18257 (2020).

Fan, C. et al. Exacerbating dam-induced fragmentation in China’s river systems. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 1–13 (2025).

Song, S. et al. Quantifying the effects of institutional shifts on water governance in the Yellow River Basin: A social-ecological system perspective. J. Hydrol. 629, 130638 (2024).

Wang, Z. & Lou, J. Some thoughts on the adjustment of Water Resources Allocation of “87 Scheme” of Yellow river (in Chinese). Yellow River 44, 1–5+27 (2022).

Ren, X., Li, P., Wang, D., Zhang, Q. & Ning, J. Drivers and characteristics of groundwater drought under human interventions in arid and semiarid areas of China. J. Hydrol. 631, 130839 (2024).

Walsh, C. L. et al. Adaptation of water resource systems to an uncertain future. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 20, 1869–1884 (2016).

Ge, Y. et al. What dominates sustainability in endorheic regions?. Sci. Bull. 67, 1636–1640 (2022).

Basheer, M. et al. Cooperative adaptive management of the Nile River with climate and socio-economic uncertainties. Nat. Clim. Chang. 13, 48–57 (2023).

Vinca, A. et al. Transboundary cooperation a potential route to sustainable development in the Indus basin. Nat. Sustain. 4, 331–339 (2021).

Harmony with water. Nat. Water 3, 509. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44221-025-00448-1 (2025).

Wang, T. et al. Unsustainable water supply from thawing permafrost on the Tibetan Plateau in a changing climate. Sci. Bull. 68, 1105–1108 (2023).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate change on water resources and agriculture in China. Nature 467, 43–51 (2010).

Lin, J. et al. Making China’s water data accessible, usable and shareable. Nat. Water 1, 328–335 (2023).

Sang, S. et al. The modeling framework of the coupled human and natural systems in the Yellow River Basin. Geogr. Sustain. 6, 100294, (2025).

Qu, W., Shi, W., Zhang, J. & Liu, T. T21 China 2050: a tool for national sustainable development planning. Geogr. Sustain. 1, 33–46 (2020).

Mialyk, O. et al. Water footprints and crop water use of 175 individual crops for 1990–2019 simulated with a global crop model. Sci. Data 11, 206 (2024).

Moallemi, E. A. et al. Early systems change necessary for catalyzing long-term sustainability in a post-2030 agenda. One Earth 5, 792–811 (2022).

Ye, Q. et al. FeliX 2.0: an integrated model of climate, economy, environment, and society interactions. Environ. Modell. Softw. 179, 106121 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Novel hybrid coupling of ecohydrology and socioeconomy at river basin scale: a watershed system model for the Heihe River basin. Environ. Modell. Softw. 141, 105058 (2021).

Herman, J. D., Kollat, J. B., Reed, P. M. & Wagener, T. Technical Note: Method of Morris effectively reduces the computational demands of global sensitivity analysis for distributed watershed models. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 17, 2893–2903 (2013).

Li, K. et al. Safeguarding China’s long-term sustainability against systemic disruptors. Nat. Commun. 15, 5338 (2024).

Chen, M. et al. A cost-effective climate mitigation pathway for China with co-benefits for sustainability. Nat. Commun. 15, 9489 (2024).

Maier, H. R. et al. An uncertain future, deep uncertainty, scenarios, robustness and adaptation: How do they fit together?. Environ. Modell. Softw. 81, 154–164 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This research was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U2243601, 42201306, 42521001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.W., L.Y., and S.W. conceived the idea and designed the research. L.Y., S.S., and Y.L. contribute to module construction and data collection. L.Y. performed the analysis and prepared the draft. X.W., S.S., Y.L., C.L., Q.Y., O.V., B.F., and S.W. revised the manuscript and provided extensive comments. All authors discussed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests. Quanliang Ye is an Editorial Board Member for Communications Sustainability but was not involved in the editorial review of this article, nor in the decision to publish it.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Sustainability thanks the, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Alireza Bahadori. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, L., Wu, X., Sang, S. et al. Yellow River Basin water stress has eased but may persist without enhanced efficiency and sustainable agriculture. Commun. Sustain. 1, 9 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00005-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00005-7