Abstract

The United States Midwest produces one-third of the global corn and soybeans. However, crop yields and prices are sensitive to extreme weather events, such as drought and extreme rainfall. While the impact of extreme weather on crop yields has been explored, the impact on crop prices is less understood. Here, we utilize weather, crop, and price data from 1971 to 2019 and analyze how changing weather patterns and extreme weather events in the United States Midwest have impacted crop valuation at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. We find that regional summer rain increased between 1971 and 2019, while extreme temperatures remained stable on average. Hot dry spells and excessive rain in the summers of 1971–2019 contributed to contemporaneous price increases for soybeans and corn. Predicted market responses to weather shocks were, in extreme cases, comparable to a 10% price increase. The market impact of excessively wet spells gained strength in later decades. Our analysis and findings have important implications for the agricultural supply chain and for crop market participants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Corn and soybeans are two of the most important sources of calories for humanity and for animal feed. The U.S. Midwest has produced in recent decades about 33% of global corn and 34% of global soybeans1. In the context of changing weather patterns, we explore the contemporaneous impact that summer weather in the U.S. Midwest had on corn and soybean prices between 1971 and 2019. We focus on futures prices at the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME), which serve as reference for global trade and that reflect expected supply and demand for the new crop that grows during the summer and is harvested in the fall.

Climate variability has explained about a third of observed global yield variability in recent decades and more than 40% in some areas of the U.S. Midwest2. Earlier work has found that high temperatures, drought and excessive rain are all detrimental to corn and soybean yields3,4,5,6,7. Low soil moisture during the middle of the growing season, which depends on precipitation, evapotranspiration driven by temperature and local soil characteristics, has recently been shown to lower corn and soybean yields8,9,10. Early work11 projected a doubling of corn output losses by 2030 relative to those in late 20th century due to increased precipitation induced by climate change in the U.S. More recent work has found a strongly negative average impact of global warming on crop yields and agricultural productivity12,13,14,15,16 that is, however, heterogeneous across space.

Negative climate effects on yields are already apparent in Europe17,18. The U.S. Midwest is expected to suffer a decrease in agricultural productivity if summer temperatures over 30 °C increase in frequency4,19. However, this negative effect has apparently not materialized yet. On the contrary, there is evidence20,21,22,23 that the U.S. Midwest has experienced increasing average yields caused not only by improving technology but also in part by a higher frequency of moderate temperatures that allow earlier planting, a decrease in the incidence of extreme temperatures and higher precipitation during the summer. However, higher corn yields have become more sensitive to droughts24, thus widening the output gap across growing conditions. Weather extremes have also increased spatial yield correlations25.

Unlike work on yields, direct estimates for the impact of weather shocks on crop prices are less common. Work closely related to ours26 found that pre-harvest weather shocks in India during 2004–2017 that were expected to damage crops were incorporated in local market prices in anticipation of reduced supply. Contemporaneous work27 studied the impact of extreme heat on U.S. corn and soybean farming revenue on yearly frequency, motivated by the potentially compensating effects of higher prices and diminished yields. Our work is complementary to ref. 27 in that we disentangle the separate impact of higher frequency extreme weather on yields and CME prices, in that we take into account the change in the distribution of weather events since 1970, and in that we identify important market impacts not only for extreme heat but also for extreme rain. Earlier related work28,29 focused on the impact of slowly moving El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) signals on the level of soybean and wheat prices. Studies have also explored the effect of the ENSO oscillation on corn and soybean price volatility30,31 and the effect of global temperature anomalies since 1999 on corn and soybeans among other commodities32. Local food prices in developing markets, mostly in Africa, are sensitive to local weather shocks proxied by variations in local vegetation indices33,34. In this paper, we focus on the market impact of changing weather patterns and high-frequency extreme events during the 1971–2019 corn and soybean growing seasons in the U.S. Midwest.

Market prices differ from yields in two fundamental aspects. First, there is no meaningful spatial heterogeneity in prices. The widely followed prices of corn and soybeans at the CME reflect global demand and aggregate expected supply including that from all of the U.S. Midwest, therefore concealing spatial variability in soil quality and climate. Second, unlike yields, which are measured once a year, crop prices are available at any time during the growing season and dynamically incorporate the most recent information on expected output at future harvest. Hence, we choose to focus on the contemporaneous response of CME market prices to regional weather shocks. These are first in the causal chain from weather to soil moisture and later yields. In addition, timely rain and temperature information has been widely followed by farmers and other market participants and has been historically available for many decades.

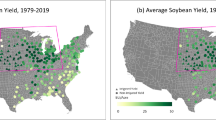

Informed by the nonlinear relationship between weather and physical output, we study the effect that U.S. Midwest weather shocks during June, July and August from 1971 to 2019 had on contemporaneous corn and soybean percentage CME price changes, also called returns. The region we consider comprises all of twelve states: Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota and Wisconsin. Our data sources for daily rain and temperature measures are 1311 weather stations (Methods). Our main findings are summarized as follows. First, we provide empirical evidence of a strong increase in summer precipitation in the U.S. Midwest over the 1971–2019 period. Then, we show that the negative response of yields to extreme heat and insufficient rain, or to excessive precipitation, was mirrored by an economically important and previously undocumented nonlinear market response to these weather events. Finally, we find that the market response to excessive precipitation gained strength in recent decades, in line with shifting weather patterns and yields’ responses to rain.

Results

Summer rain increased in the U.S. Midwest while extreme temperatures remained stable

We investigate the potential existence of a statistically and agronomically relevant shift in the distribution of daily rain and temperature variables in the U.S. Midwest between 1971 and 2019. While climate change induced by global warming is a global phenomenon, its expression is highly heterogeneous across countries and regions. Our approach to assess potential changes in weather patterns in the U.S. Midwest is agnostic and data-driven. Because crop prices at the CME respond to aggregate supply including that from the entire U.S. Midwest, it is relevant to analyze the behavior of rain and temperature time series constructed as spatial averages over the entire region. Alternative averaging schemes, including weighting weather variables in each state by state share of crop production, led to very similar results to those presented in this paper. In addition, we complement our regional analysis with local tests to uncover potential spatial heterogeneity.

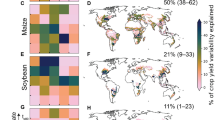

Weather data sources are described in “Methods” (Section “Weather data”). Table S.1 (Supplementary Information) presents summary statistics for weather variables at daily and monthly frequencies from June to August in each year between 1971 and 2019. Spatially averaged daily rain was 31.6 tenths of a mm. Regressions of spatially averaged daily precipitation as functions of time uncover a positive trend for the 1971–2019 period with an average yearly increase of 0.113 tenths of a mm in daily rain. (Supplementary Information, columns (1)–(4) in Table S.2). This trend suggests an increase of ~5.5 tenths of a mm between the start and the end of our sample period. The cumulative effect of trending rain is apparent in the comparison of precipitation measures for various time intervals anchored at the start and end of the 1971–2019 period. Figure 1a shows a strongly significant increase in June–August precipitation for the U.S. Midwest and for all of its states across time periods. Results for change in mean tests for average daily rain in earlier and later periods in our sample (1971–1990 vs 2000–2019 and 1971–1985 vs 2005–2019) are in (Supplementary Information, columns (1)–(4) of Table S.3). Figure 1c shows the percentage difference in summer precipitation in U.S. Midwest counties, comparing the 1971–1990 period against 2000–2019. Although some counties had a decline in mean precipitation, the rise was largely homogeneous in space and important in magnitude. Alternative tests with year fixed effects rather than a constant yearly trend show that multiple years towards the end of our sample period had significantly higher summer precipitation than those in the earliest part of the sample (Supplementary Information, columns (1)–(4) of Table S.4). In sum, across econometric specifications we find a statistically and agronomically large increase in rain during the growing seasons between 1971 and 2019. Increases in average and extreme rain in the Midwest and other U.S. regions have been reported in earlier work20,35,36,37,38,39. Attribution of rain increase to anthropogenic warming has gained strength in recent years, but natural decadal climate variability should not be disregarded40,41. We interpret the magnitude of our estimates as evidence of changing weather patterns but refrain from claiming a direct causal link to global warming.

Changes in rain and Extreme Degree Day averages in the U.S. Midwest for June, July and August, 1971–2019. a The change in daily mean county rain in the U.S. Midwest and in individual states across time. b The change in daily mean EDD for the U.S. Midwest and individual states across time. c Differences in county mean daily rain between 2000–2019 and 1971–1990. d Differences in county mean daily EDD between 2000–2019 and 1971–1990. Error bars in figures (a, b) represent 95% confidence intervals.

Tests for changes in spatially averaged extreme summer temperature measures in the U.S. Midwest were much less conclusive than for rain. We focus our analysis on Extreme Degree Days (EDD), defined for a given day and location as a piecewise linear function that takes the value of zero if local daily temperature is below 30 °C and the linear excess over this threshold otherwise. EDD has been widely validated in the literature as a measure of high temperature that is harmful for U.S. Midwest crops4. In contrast with rain, we find that EDD showed no consistent yearly trend when averaged over the U.S. Midwest (Supplementary Information, columns (5)–(8) of Table S.2). Figure 1b and estimates in Supplementary Information, columns (5)–(8) of Table S.3 show no consistent regional pattern of significant differences in EDD across decades. While the eastern and southern edges of the U.S. Midwest seem to have warmed up slightly on average, this is not the case for its central part that exhibits many instances of cooling (Fig. 1d), in line with earlier work20. A yearly fixed effect analysis (Supplementary Information, columns (5)–(8) of Table S.4) also shows no clear pattern of an increase in extreme temperatures across decades.

The literature20,22 has found a decrease in extreme heat events in certain parts of the U.S. Midwest by studying centennial trends, differences across non-consecutive decades and agricultural intensification at the county and weather station level. Perhaps as a consequence of our spatial averaging, and unlike the case of rain, we find no consistent pattern of summer temperature changes across the U.S. Midwest as a whole since 1971.

Weather patterns in the U.S. Midwest during the summer are often the consequence of structured fronts that tend to flow eastwards and last for several days. These are widely followed by farmers and market participants. Thus, we construct weather events defined by patterns of precipitation that last several days. We define a dry spell (wet spell) as a sequence of two or more consecutive days in which the measure of spatially averaged daily rain was below (above) 30 tenths of a mm for every day in the event. Because 30 tenths of a mm was the mean daily precipitation for 1971–1990, dry and wet spells can be interpreted as episodes of precipitation above or below the level expected by market participants based on earlier experience. Nearby thresholds, including 31.6 tenths of a mm that was the average daily rain for 1971–2019, led to a very similar set of events. In addition, days that do not belong in a dry or wet spell are assigned to a normal weather event. In this manner, summers are decomposed as a sequence of three types of weather events that alternate along time. Details of the weather event construction are in “Methods”, Section “Weather events”. Summary statistics for weather events are in (Supplementary Information, Table S.5).

Hot dry spells and heavy rain led to lower yields and increases in new crop prices

An extensive literature has found that crop yields in the U.S. Midwest display an inverted-U response to summer precipitation and a strongly decreasing response to EDD3,4,5,6,7. We build on these findings to propose a model for the relationship between weather shocks, changes in expected terminal yields and market returns. We focus on the response of corn and soybean yields to weather shocks that occurred in the U.S. Midwest during June, July and August, which are months after planting and before harvest for these crops. Changes in expected output during these months are largely determined by weather. A model for the nonlinear relationship between local yields, local rain and temperature is presented in “Methods”, Section “A model for weather and crop returns”. We estimate this model using a panel of yearly county-level data on yields regressed on county-level weather measures recorded monthly for the year in which the yield is observed. Regression specifications are in “Methods”, Section “Regression specifications”. This approach takes advantage of yields’ rich spatial heterogeneity while being aligned with yields’ low time frequency. Estimated models in Supplementary Information, Table S.6 show strongly significant linear and quadratic rain coefficients for both crops, in line with the notion that very dry or excessively rainy months hurt crops, and a generally negative response to EDD. The response of yields to GDD is mixed, with three monthly coefficients being positive and consistent with the favorable impact of GDD on plant growth, and two negative coefficients. Figure 2a displays predicted yields as a function of monthly precipitation for various levels of monthly EDD. Point estimates for average rainfall magnitudes that maximized predicted corn and soybeans yields (“Methods”, Section “Regression specifications”) were 1714 and 1729 tenths of mm per month, respectively, or ~56 tenths of a mm per day. These optimal precipitation levels are close to earlier estimates3,5. In addition, the correlation between spatially averaged monthly rain and EDD in 1971–2019 was –0.29, with dry months frequently having EDD above 20 and no month simultaneously having rain above 1500 tenths of a mm and EDD above 3. Hence, the most harmful months were those either excessively rain yet cool, or simultaneously hot and dry.

a Predicted corn and soybean yields for monthly precipitation and various levels of monthly EDD, estimated on county-level data. For displaying purposes, all three months in the summer are assumed to have the same monthly rain and EDD. Bands represent 95% confidence intervals for fitted models. Estimates are in (Supplementary Information, Table S.6). b Observed weather event features and predicted market returns as a function of precipitation deviations and EDD over the entire U.S. Midwest. Shown in color are predicted values that are statistically different from zero at the 5% significance level. c Market returns contemporaneous with weather events and alternative fitted models as a function of precipitation deviations over the U.S. Midwest. Bands represent 95% confidence intervals for fitted models. Estimates for (b, c) are in Supplementary Information, Table S.7.

Informed by the nonlinear response of yields to weather shocks, we test for the market response to the accumulation of precipitation or temperature away from their optimal levels for crop growth. Unlike yields, which are observed once a year, market prices are available every trading day during the summer. We work with futures contracts that are traded daily at the CME during the growing season and expire in November (for soybean) or December (for corn) of each year in our sample. A futures contract essentially endows its buyer with the right and obligation to acquire a certain crop on expiration date in exchange for the price set by the market at the original trading date. Futures prices for a fixed delivery date fluctuate during the growing season in response to variations in expected supply driven by weather shocks. In our market return estimations we choose to work under the time frequency dictated by the duration of dry spells, wet spells and normal events. There are an average 19.6 events per summer in 1971–2019 (Supplementary Information, Table S.5), hence this frequency allows us to exploit the rich contemporaneous variation in market prices in response to the potentially substantial rain and temperature deviations associated with weather events. We associate with each weather event a precipitation magnitude defined as the amount of rain fallen during the duration of the event minus our yield-based point estimate for optimal monthly precipitation linearly scaled by the length of the event measured in days. The model in (“Methods”, Section “A model for weather and crop returns”) accounts for price changes driven by weather shocks by equation (“Methods”, Eq. (4)). Our base model is piecewise quadratic on precipitation deviations to estimate the impact of insufficient and excessive rain separately. For robustness, we estimate alternative models by regressing crop market returns on piecewise linear and spline functions of contemporaneous precipitation deviations. All specifications include EDD, GDD, interaction terms and economic controls (“Methods”, Section “Regression specifications”). Estimated coefficients are in Supplementary Information, Table S.7. Under the baseline piecewise quadratic model, returns for both crops exhibited strongly significant positive response to excessive precipitation events. Rain deficits led to positive returns, strongly in soybeans but not conclusively in corn. Under the piecewise linear model, which also allows for a non-monotone market response to rain, both insufficient and excessive rain contributed to higher crop prices. The interaction term defined as the product of precipitation deviation and EDD was strongly negative in the case of corn for all three specifications. This suggests that episodes that combined rain deficits with high temperatures led to higher corn prices. Figure 2b shows precipitation deviations and EDD for weather events (capped at EDD = 20 for displaying purposes), and predicted market returns estimated from contemporaneous weather events (at mean values for other regressors) using estimates from the quadratic specification in Supplementary Information, Table S.7. Figure 2b shows that dry spells often coincided with high temperatures while excessive precipitation was associated with cooler weather. We find that predicted market returns for hot dry spells and strong wet spells were significant and positive. In extreme cases, in excess of a 10% price increase, which implies a large economic impact. In addition, optimal precipitation under mild temperature was associated with negative returns. Predicted returns for all specifications in Supplementary Information, Table S.7 are computed at mean EDD and presented together with observed market returns in Fig. 2c. Precipitation deviations contributed towards significantly positive returns. Fitted models in Fig. 2c provide a conservative estimate for the strength of dry spells impact because, as seen in Fig. 2b, precipitation deficits had positive correlation with high EDD, which also contributes towards positive returns.

Potential concerns about the results behind Fig. 2 could include lack of robustness with respect to our event time frequency or to the definition of rain deviation in terms of a predetermined optima. To alleviate these potential concerns we run return regressions of weekly market returns on contemporaneous unnormalized precipitation data and let the estimation identify the amount of rain, if any, that minimizes returns. Results in Supplementary Information, Table S.8 show that market returns for both crops have negative linear and positive quadratic responses to weekly precipitation. Combined, the terms that involve precipitation imply a nonlinear response that contributes towards positive returns for both low and high weekly precipitation. Point estimates for the amount of weekly rain that minimizes returns are at 280 and 266 tenths of a mm for corn and soybean, respectively. This is ~30% lower than the optimal precipitation inferred from yield regressions in Supplementary Information, Table S.6 on monthly data and linearly scaled to weekly frequency. Beyond estimation noise, potential explanations for this difference include a more nuanced relationship between yields and rain than in equation (“Methods”, Eq. (2)), monthly vs weekly estimation frequencies, and forms of risk aversion among market participants that would bring prices away from fundamentals. Unreported results on daily frequency were less significant than those presented in this paper. We attribute this to a signal-to-noise ratio in daily data that is lower than that implicit in longer precipitation events which allows for an agronomically significant accumulation of rain and heat. We also considered regression specifications using the contribution of the U.S. Midwest to global output, rather than U.S. output, as weighting factor for weather shocks. This is to reflect that CME prices aggregate to some extent supply and demand beyond the U.S. Unreported estimates imply quantitatively similar weather price impact after adjustment for the change in weighting. This simply reflects that market shares are very slowly moving variables across decades and unrelated to short-term weather fluctuations. We do not include weather shocks in Latin America in our regressions because for them to introduce a bias in our estimates two conditions must hold simultaneously: (1) short-term weather shocks in the U.S. Midwest during the summer months (June, July and August) should be correlated with contemporaneous weather shocks in Latin America (their winter months) and (2) weather shocks in Latin America during these months should impact local yields. However, both conditions are likely weak. First, while there has been some evidence of long-term correlation between seasonal weather in the U.S. and Latin America driven by ENSO, this mechanism would not induce correlations on contemporaneous weather at both locations in the timescale of days or weeks, which are those used in our price return regressions. Second, the growing season for Argentinian and the majority of Brazilian corn/soybean output, including the safrinha (second crop), ranges from October to May. During June, July and August corn/soybeans growth in the Southern Hemisphere is limited; therefore, weather shocks during these months would have a lesser impact on regional yields.

Finally, we conducted a placebo test regressing market price returns for wheat, which is a winter crop, during the growing season for corn and soybeans. Our estimates (Supplementary Information, Table S.9) find no effect for summer weather shocks on wheat. In sum, given the simplicity of our model for yields and returns, and the noise around our estimates, we interpret our results as generally supportive for the notion that agricultural commodity markets were pricing the nonlinear impact of weather variables in manner that was compatible with production fundamentals.

Crop prices increasingly responded to excessive precipitation

In the previous section, we found that, over the full 1971–2019 sample, hot dry spells and excessive rain events were conducive to higher crop prices. Has the significance of these two kinds of events changed as precipitation gained strength in the U.S. Midwest between 1971 and 2019? We explore this question by estimating the model in (“Methods”, Section “A model for weather and crop returns”) on the two earliest and two latest decades in our sample. These are time intervals sufficiently long for statistical estimation, yet far enough from each other in time to differ in their weather patterns (Fig. 1). Yield estimates are in Supplementary Information, Table S.10. Figure 3a displays fitted models for corn and soybean yields as a function of monthly precipitation for various levels of EDD. Maximum crop yields in 2000–2019 were substantially higher than those in 1971–1990, driven partially by agronomic practices and technology23.

a Predicted corn and soybean county yields for monthly precipitation and various levels of EDD, estimated on county-level data. For displaying purposes, all three months in the summer are assumed to have the same monthly rain and EDD. Bands represent 95% confidence intervals for fitted models. Estimates are in Supplementary Information, Table S.10. b, c Predicted market returns as a function of precipitation deviations and EDD for the entire U.S. Midwest. Shown in color are predicted values that are statistically different from zero at the 5% significance level. Estimates are in Supplementary Information, Table S.11.

Figure 3b displays fitted piecewise quadratic models for corn and soybean market returns in 1971–1990, as a function of precipitation deviations and EDD, while holding other variables at their mean levels. Estimates are in Supplementary Information, Table S.11. In this exercise, we use deviations from optimal rain estimates based on 1971–2019 (Supplementary Information, Table S.6). In 1971–1990, hot dry spells made a statistically strong and positive contribution to corn and soybean returns mediated by the interaction term in the estimated model. Figure 3b also shows that high temperatures under optimal precipitation made a negative contribution to corn returns and had no significant effect on soybean returns. In 2000–2019, episodes of excessive precipitation were stronger than in 1971–1990. Mean and maximum wet spells increased from 171 and 621 in earlier decades to 196 and 800 tenths of a mm in later decades (Supplementary Information, Table S.5). Figure 3c shows that, as larger precipitation events materialized in 2000–2019, excessive rain became statistically significant in contributing to positive returns in both crops. Interaction terms for precipitation and EDD seemed to weaken in magnitude and remained significant only for corn in the last two decades of our sample. As robustness, we also consider rain deviations defined in terms of optimal precipitation estimated separately for each crop and period. Point estimates for optimal mean daily precipitation were close to 54 and 48 tenths of a mm for corn and soybeans, respectively, during 1971–1990, and at 58 and 59 tenths of a mm during 2000–2019. Results in Supplementary Information, Fig. S.2 (a,b) and Table S.12 largely agree with Fig. 3. Hence, we find that shifting weather patterns in the U.S. Midwest were mirrored by market responses consistent with production fundamentals.

Discussion

The main contribution of this paper is a characterization of the effects of extreme weather and changing weather patterns in the U.S. Midwest, a major producing region, on new crop corn and soybean prices. We began by documenting a positive trend in summer precipitation in the U.S. Midwest between 1971 and 2019. Spatially averaged summer precipitation increased by ~15% between 1971 and 2019. Spatially averaged extreme temperatures did not show a changing pattern during this period. Next, we found that dry spells contributed to higher prices and that this effect was amplified by extreme heat in the form of EDD. Hot dry spells led to predicted CME price increments potentially in excess of 10%. This is highly relevant in economic terms. In more recent decades, as precipitation became more intense, events associated with excessive rain contributed more strongly towards positive market returns. This effect was not visible in the first 20 years in our sample. The nonlinear market response to precipitation and EDD was generally consistent in its shape with the estimated impact of rain and temperature on yields. In this paper, we estimate the response of crop prices to contemporaneous weather events. We do not explore the effect of extreme weather events on long-term or multi-year prices. But, as short-term weather shocks have a real impact on yields and market participants are rational and forward looking, it is sensible to interpret these price movements as non-transient in the context of the current season. Advances in agronomic practices, including adaptation in response to climate change42,43,44,45,46, are likely to mitigate the impact of weather on yields and might have modulated the impact of weather on markets. Disentangling the precise time-varying contribution of climate adaptation from the high-frequency link between weather and crop prices is challenged by the lack of spatial variability in prices. Increase in irrigation, that as of 2024 is still used in a very minor proportion of corn and soybean farms in the U.S. Midwest, could weaken the link between scarce rain and returns but could potentially strengthen, through evapotranspiration, the market impact of excessive precipitation20.

Our findings complement earlier work on the effect of shifting weather patterns on agriculture in the U.S. Midwest4,20,21,22,23. An explicit distinction has been made47 between the positive impact of higher precipitation on U.S. corn and soybean yields, and the negative yield impact of the most extreme hourly rain episodes. We find that for rain to contribute to higher prices, it must be not just higher than the historical average (31.6 tenths of a mm per day) but also surpass a larger agronomical optimal. This suggests that market participants are aware of the differential impact of various rain magnitudes. The market impact of dry heat in corn is consistent with the damage provoked by extreme dry heat on yields48. Our paper is an early contribution to a research agenda on valuation and risk management in crop markets under climate risk. Potential avenues for future work include quantifying the impact of compound extremes in market prices48,49, exploring the interplay between weather shocks, planting decisions during spring and market returns; and exploring the empirical performance of more complex models that condition the impact of an extreme weather event on moisture or accumulated precipitation since the start of the summer.

Our findings suggest that the negative effects of extreme weather on agricultural output and economic activity would also operate through sharp price increases with potential redistributive effects. Local farmers affected by a negative output shock could be partially compensated by higher prices50. Given the integrated nature of corn and soybean markets, producers in Brazil, Argentina and elsewhere could benefit from higher prices51. And consumers around the world would face higher costs, increased volatility and potential food insecurity52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59. Corn price spikes would also interact with the energy sector through the ethanol mandate60. Coupling our estimated crop price responses with long-term forecasts from large-scale climatological models may contribute to better long-term economic forecasts and food price volatility estimates.

Methods

Weather data

We obtained daily precipitation and temperature data from NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association)’s GHCN (Global Historical Climate Network) dataset. We focus on data for June, July and August in the U.S. Midwest from 1971 to 2019. Some weather stations have missing data on certain dates, so we kept for our regressions those that cover (i.e., have non-missing data) at least 50% of the period. This left us with 1311 weather stations for precipitation and 960 stations for temperature, roughly evenly distributed across the twelve states of the Midwest (Supplementary Information, Fig. S.1). Table S.1 in the Supplementary Information displays summary statistics for our raw weather data. Rain and temperature are reported in daily and monthly frequencies, and averaged over the U.S. Midwest. In line with the literature, we report summary statistics for Growing Degree Days (GDD) and EDD, which measure the exposure that crops have experienced to healthy growing conditions and to excessively hot weather, respectively.

Weather events

We decompose each summer in a temporal sequence of weather events in which dry, normal and wet spells alternate with each other during summers from 1971 to 2019. We proceed as follows. Let Rt be the spatial average of rain fallen over the U.S. Midwest on day t, where all 7 days of the week are treated equally. Let Ft represent rain information learnt by market participants on trading day t. We adopt Ft = Rt except for Mondays in which Fmonday = Rsaturday + Rsunday + Rmonday to incorporate information on the most recent weekend. A wet spell is defined as two or more consecutive trading days where Ft in each trading day is above a certain threshold. For Tuesdays to Fridays, we set the threshold at 30 tenths of a mm, which is close to the mean daily rain for the 1971–1990 period. For Mondays, the threshold is 90 tenths of a mm to account for the fact traders incorporate on this day information revealed during the weekend. A dry spell is two or more consecutive days with Ft lower than the aforementioned thresholds. Days not in a wet or a dry spell belong to a normal event. Defined in this manner, wet spells can be interpreted as multi-day events with higher than usual rain.

Additional data sources

Data on corn and soybean futures contracts prices were gathered from Reuters Datastream. From Federal Reserve Economic Data St. Louis we gathered daily data on spot crude oil price (WTI). We use the “Nominal Broad Dollar Index - Goods Only" from the Federal Reserve Bank for a measure of the exchange rate/strength of the U.S. dollar. Our choice of controls is standard in the literature. The oil price is included as a control as it relates to global commodity demand and crop production costs. To account for demand fluctuations, we also considered the Baltic dry index on a daily basis since 1985. Corn and soybean yields per state, inventories and planted area on yearly frequency were gathered from the USDA.

A model for weather and crop returns

An extensive literature relates weather to crop yields. Work4 relying on U.S. data between 1950 and 2005 found that corn and soybean yields had an inverse U-shaped response to rain during the growing season from May to August. Rain is beneficial to crops up to a certain threshold. Beyond that, crops suffer. Crop yields were slightly increasing as a function of temperature up to the vicinity of 30 °C, and sharply decreasing after exposure to temperatures beyond that threshold. Results5 on data for the United States from 1977 to 2007 show that corn and soybean yields had an inverse U-shaped response to monthly rain during June, July and August, were positively related to GDD and negatively related to EDD (defined as Overheat Degree Days5). Earlier work3 used data between 1960 and 2006 for Indiana, Illinois and Iowa, to find an inverted-U relationship between corn and soybean yields in the U.S. Midwest and rain in each of the months of June, July and August. These studies found that corn and soybean yields were generally increasing for up to the vicinity of 6 inches (1524 tenths of mm) of monthly summer rain and had a tendency to decrease for heavier precipitation. The nonlinear relationship between yield and temperature between 1950 and 1977 was the same as the one between 1978 and 20054.

We explore the effect of weather shocks on the dynamics of crop prices. Farmers in twelve states in the U.S. Midwest grow corn and soybeans and sell their output in a competitive market. We focus on corn and soybean price changes during a single growing season, after seeds have been planted at t = 0. This allows us to assume that output variations at harvesting time T at the end of the summer are due to yield variability caused by weather shocks in June, July and August, and not due to planting decisions. Regional output is harvested at T and added to typically small existing stocks, for final supply Qyear. Expected supply, conditional on information available to participants at the CME during the growing summer at time t ≤ T is

Uncertainty about supply at harvesting time is a function of the yield per unit of land, which depends on the technology chosen prior to the growing season and on weather. In the absence of irrigation, as it is the case for the vast majority of corn and soybeans in the U.S. Midwest, water intake is provided exclusively by rain. We split the summer in non-overlapping periods j = 1, . . . , N, to model the link between weather and terminal yields on time periods that allow for the accumulation of a material amount of rain or heat. Let Rj, GDDj and EDDj be the spatial averages of rain, GDD and EDD that occurred during period j over the U.S. Midwest. Let Yyear,T be the terminal yield that will be observed at T in year. Based on the nonlinear relationship between weather and yields identified in the literature4, we postulate that

where α1 < 0, α2 > 0, α3 < 0, and Yyear,0 is the predictable component of trending yields across years due to technological innovation. In this expression, R* is the agronomically optimal amount of rain. Insufficient or excessive precipitation hurts crops. In the case of a monthly partition for the summer, earlier estimates suggest R* in the vicinity of 1500–1600 tenths of a mm3.

Market expectations of terminal output are updated during the summer. We assume that short-term weather shows no predictability in time beyond very short-term forecasts available at the start of period j. Therefore, the change in expected terminal output that occurs during period j depends on weather measures revealed contemporaneously. Let Ej be the conditional expectation based on information available at the start of period j. Taking conditional expectations in 2, we write

where EW is the unconditional expectation of weather shocks (precipitation and temperature) for period j. Weather-related contributions in 2 associated to periods other than j are either known if they already occurred, or have the same conditional expected value as seen from periods j and j + 1. Hence, they all cancel away and do not contribute to (3). The change in expected output in period j is driven exclusively by weather shocks at j. Let \({P}_{j}^{T}\) be the price observable at j ≤ T associated with a CME future contract expiring at T. Let Ayear be the planted area in the U.S. Midwest so that terminal supply is Qyear = AyearYyear,T. Under a standard model61 for supply and demand for T, with constant elasticities and multiplier β > 0, the percentage price change between the start of period j and the start of period j + 1 due to an exogenous supply shock is

where

is a measure of the importance of U.S. Midwest production in the U.S or global market for corn or soybeans (before being multiplied by local yield variations). Crop prices are also influenced by global demand fluctuations that we assume uncorrelated to local weather. These and other financial variables are taken into consideration in the empirical estimation of the model through appropriate controls.

Regression specifications

Our regressions for yields on weather data are motivated by Eq. (2). To uncover the response of yields to weather shocks, including the precipitation amount that maximizes yields, we regress

The subscripts in (6) refer to individual counties (c), year (y) and month (m = June, July and August). Y is the annual yield (measured in bushels per acre), and R, GDD and EDD are, respectively, rain, EDD and GDD accumulated over a month during the summer. County-level daily weather was constructed from NOAA’s GHCN station data by assigning stations to counties based on their geographic location and averaging observations within each county. Missing counties were imputed using averages from adjacent counties. County-fixed effect μc controls for average county yield, and year-fixed effect λy for time-varying regional shocks common to all counties. These parameters seek to control for technological change, among other non weather-related factors. The amount of precipitation that maximizes the contribution of pure rain terms to yields is \(\frac{-{\beta }_{1,m}}{2{\beta }_{2,m}}\). In the presence of a significant interaction term, the amount of rain that maximizes yields can be approximated by \(\frac{-{\beta }_{1,m}-{\beta }_{5,m}\overline{EDD}}{2{\beta }_{2,m}}\) where \(\overline{EDD}\) is the mean value of EDD. Based on 1971–2019 monthly data and averaged over the summer, estimates for optimal rain for both definitions and crops lie between 52 and 57 tenths of a mm per day. In addition, we show in Supplementary Information, Tables S.8, S.11 and S.12 that our findings for the market response to extreme precipitation are robust to small variations in R*. Our regressions for crop returns on weather data are grounded on Eq. (4) and their structure is

where \(\frac{{P}_{j+1}^{T}-{P}_{j}^{T}}{{P}_{j}^{T}}\) is the percentage price change, or return, of a crop future contract during time period j. The optimal amount of rain \({R}_{j}^{* }\) is simply the R* estimated from yields and monthly rain, linearly scaled by the length of period j in days. Hence, \({R}_{j}-{R}_{j}^{* }\) can be interpreted as the deviation from optimal precipitation contemporaneous to the crop market return. The weight W captures the share of the U.S. Midwest in the market for that crop. In our empirical work, we construct a measure for Wj using physical production forecasts and inventories measures available on May of each year and leave Wj constant during each summer. Alternative inventory measures62 are constructed using low-frequency data from USDA published statistics (therefore already in physical units) and a higher-frequency inventory proxy given by the slope of the term structure that correlates strongly with inventories but has no physical units. Because the determination of \({P}_{j}^{T}\) depends on the combined effect of expected global output at T and available inventories in the denominator of Eq. (5), we choose to work with statistics published in May of each year on existing inventories and expected output. Standard controls to explain price changes, when available in the frequency of our weather variables, are the contemporaneous returns on the WTI spot crude oil price, the Nominal Major Currencies Dollar Index (Goods Only) from the U.S. Federal Reserve, the Baltic Dry Index that captures global commodity demand. By working with returns and local shocks, all variables included in Eq. (7) are stationary and all regressors are plausibly exogenous.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available on Code Ocean at: https://codeocean.com/capsule/8234540/tree/v1.

Code availability

The source codes in R for generating the results of this manuscript are available in cloud-based computational reproducibility platform CodeOcean at: https://codeocean.com/capsule/8234540/tree/v1.

References

Wang, S., Di Tommaso, S., Deines, J. M. & Lobell, D. B. Mapping twenty years of corn and soybean across the US Midwest using the Landsat archive. Sci. Data 7, 307 (2020).

Ray, D. K., Gerber, J. S., MacDonald, G. K. & West, P. C. Climate variation explains a third of global crop yield variability. Nat. Commun. 6, 5989 (2015).

Tannura, M., Irwin, S. & Good, D. Weather, technology, and corn and soybean yields in the U.S. Corn Belt. Marketing and Outlook Research Report 2008-01 (Department of Agricultural and Consumer Economics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2008).

Schlenker, W. & Roberts, M. Nonlinear temperature effects indicate severe damages to U.S. crop yields under climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 15594–15598 (2009).

Miao, R., Khanna, M. & Huang, H. Responsiveness of crop yield and acreage to prices and climate. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 98, 191–211 (2016).

Lesk, C., Rowhani, P. & Ramankutty, N. Influence of extreme weather disasters on global crop production. Nature 529, 84–87 (2016).

Vogel, E. et al. The effects of climate extremes on global agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 054010 (2019).

Ortiz-Bobea, A., Wang, H., Carrillo, C. M. & Ault, T. R. Unpacking the climatic drivers of US agricultural yields. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 064003 (2019).

Rigden, A., Mueller, N., Holbrook, N., Pillai, N. & Huybers, P. Combined influence of soil moisture and atmospheric evaporative demand is important for accurately predicting US maize yields. Nat. Food 1, 127–133 (2020).

Proctor, J., Rigden, A., Chan, D. & Huybers, P. More accurate specification of water supply shows its importance for global crop production. Nat. Food 3, 753–763 (2022).

Rosenzweig, C., Tubiello, F. N., Goldberg, R., Mills, E. & Bloomfield, J. Increased crop damage in the US from excess precipitation under climate change. Glob. Environ. Change 12, 197–202 (2002).

Lobell, D. B., Schlenker, W. & Costa-Roberts, J. Climate trends and global crop production since 1980. Science 333, 616–620 (2011).

Hsiang, S. et al. Estimating economic damage from climate change in the United States. Science 356, 1362–1369 (2017).

Zhao, C. et al. Temperature increase reduces global yields of major crops in four independent estimates. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 9326–9331 (2017).

Jägermeyr, J. et al. Climate impacts on global agriculture emerge earlier in new generation of climate and crop models. Nat. Food 2, 873–885 (2021).

Ortiz-Bobea, A., Ault, T. R., Carrillo, C. M., Chambers, R. G. & Lobell, D. B. Anthropogenic climate change has slowed global agricultural productivity growth. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 306–312 (2021).

Moore, F. C. & Lobell, D. B. The fingerprint of climate trends on European crop yields. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2670–2675 (2015).

Brás, T. A., Seixas, J., Carvalhais, N. & Jägermeyr, J. Severity of drought and heatwave crop losses tripled over the last five decades in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 065012 (2021).

Lobell, D. B. et al. The critical role of extreme heat for maize production in the United States. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 497–501 (2013).

Mueller, N. D. et al. Cooling of US Midwest summer temperature extremes from cropland intensification. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 317–322 (2016).

Tollenaar, M., Fridgen, J., Tyagi, P., Stackhouse Jr, P. W. & Kumudini, S. The contribution of solar brightening to the us maize yield trend. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 275–278 (2017).

Butler, E. E., Mueller, N. D. & Huybers, P. Peculiarly pleasant weather for US maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 11935–11940 (2018).

Rizzo, G. et al. Climate and agronomy, not genetics, underpin recent maize yield gains in favorable environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2113629119 (2022).

Lobell, D. B., Deines, J. M. & Tommaso, S. D. Changes in the drought sensitivity of US maize yields. Nat. Food 1, 729–735 (2020).

Tack, J. B. & Holt, M. T. The influence of weather extremes on the spatial correlation of corn yields. Clim. Change 134, 299–309 (2016).

Letta, M., Montalbano, P. & Pierre, G. Weather shocks, traders’ expectations, and food prices. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 104, 1100–1119 (2022).

Lee, S. Effects of extreme heat events on crop revenues for us corn and soybeans. Am. J. Agric. Econ.https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/ajae.12527 (2025).

Keppenne, C. L. An ENSO signal in soybean futures prices. J. Clim. 8, 1685–1689 (1995).

Ubilava, D. The ENSO effect and asymmetries in wheat price dynamics. World Dev. 96, 490–502 (2017).

Peri, M. Climate variability and the volatility of global maize and soybean prices. Food Secur. 9, 673–683 (2017).

Su, Y., Liang, C., Zhang, L. & Zeng, Q. Uncover the response of the US grain commodity market on El Niño–Southern Oscillation. Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 81, 98–112 (2022).

Makkonen, A., Vallström, D., Uddin, G. S., Rahman, M. L. & Haddad, M. F. C. The effect of temperature anomaly and macroeconomic fundamentals on agricultural commodity futures returns. Energy Econ. 100, 105377 (2021).

Brown, M. E. & Kshirsagar, V. Weather and international price shocks on food prices in the developing world. Glob. Environ. Change 35, 31–40 (2015).

Hatzenbuehler, P. L., Abbott, P. C. & Abdoulaye, T. Growing condition variations and grain prices in Niger and Nigeria. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 47, 273–295 (2020).

Kunkel, K. E., Easterling, D. R., Redmond, K. & Hubbard, K. Temporal variations of extreme precipitation events in the United States: 1895-2000. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1900–1903 (2003).

Arguez, A. et al. NOAA’s 1981–2010 US climate normals: an overview. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 1687–1697 (2012).

Feng, Z. et al. More frequent intense and long-lived storms dominate the springtime trend in central US rainfall. Nat. Commun. 7, 13429 (2016).

Davenport, F. V. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Using machine learning to analyze physical causes of climate change: A case study of US Midwest extreme precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL093787 (2021).

Davenport, F. V., Burke, M. & Diffenbaugh, N. S. Contribution of historical precipitation change to US flood damages. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2017524118 (2021).

Armal, S., Devineni, N. & Khanbilvardi, R. Trends in extreme rainfall frequency in the contiguous United States: Attribution to climate change and climate variability modes. J. Clim. 31, 369–385 (2018).

Lesk, C. & Anderson, W. Decadal variability modulates trends in concurrent heat and drought over global croplands. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 055024 (2021).

Mase, A. S., Gramig, B. M. & Prokopy, L. S. Climate change beliefs, risk perceptions, and adaptation behavior among Midwestern US crop farmers. Clim. Risk Manag. 15, 8–17 (2017).

Hatfield, J., Wright-Morton, L. & Hall, B. Vulnerability of grain crops and croplands in the Midwest to climatic variability and adaptation strategies. Clim. Change 146, 263–275 (2018).

Liu, L. & Basso, B. Impacts of climate variability and adaptation strategies on crop yields and soil organic carbon in the US Midwest. PLoS ONE 15, e0225433 (2020).

Sloat, L. L. et al. Climate adaptation by crop migration. Nat. Commun. 11, 1243 (2020).

Rising, J. & Devineni, N. Crop switching reduces agricultural losses from climate change in the United States by half under RCP 8.5. Nat. Commun. 11, 4991 (2020).

Lesk, C., Coffel, E. & Horton, R. Net benefits to US soy and maize yields from intensifying hourly rainfall. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 819–822 (2020).

Ting, M. et al. Contrasting impacts of dry versus humid heat on US corn and soybean yields. Sci. Rep. 13, 710 (2023).

Haqiqi, I., Grogan, D. S., Hertel, T. W. & Schlenker, W. Quantifying the impacts of compound extremes on agriculture. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 25, 551–564 (2021).

Sajid, O., Ifft, J. & Ortiz-Bobea, A. The impact of extreme weather on farm finances: farm-level evidence from Kansas https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/335443.

Headey, D. & Hirvonen, K. Higher food prices can reduce poverty and stimulate growth in food production. Nat. Food 4, 699–706 (2023).

Ahmed, S. A., Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Hertel, T. W. Climate volatility deepens poverty vulnerability in developing countries. Environ. Res. Lett. 4, 034004 (2009).

Nelson, G. C. et al. Climate change effects on agriculture: economic responses to biophysical shocks. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3274–3279 (2014).

Bellemare, M. F. Rising food prices, food price volatility, and social unrest. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 97, 1–21 (2015).

Headey, D. D. & Martin, W. J. The impact of food prices on poverty and food security. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 8, 329–351 (2016).

Haile, M. G., Wossen, T., Tesfaye, K. & von Braun, J. Impact of climate change, weather extremes, and price risk on global food supply. Econ. Disasters Clim. Change 1, 55–75 (2017).

Davis, K. F., Downs, S. & Gephart, J. A. Towards food supply chain resilience to environmental shocks. Nat. Food 2, 54–65 (2021).

Hasegawa, T. et al. Extreme climate events increase risk of global food insecurity and adaptation needs. Nat. Food 2, 587–595 (2021).

De Winne, J. & Peersman, G. The adverse consequences of global harvest and weather disruptions on economic activity. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 665–672 (2021).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Hertel, T. W., Scherer, M. & Verma, M. Response of corn markets to climate volatility under alternative energy futures. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 514–518 (2012).

Varian, H. R. Intermediate Microeconomics with Calculus: A Modern Approach (WW Norton & Company, 2014).

Bruno, V. G., Büyükşahin, B. & Robe, M. A. The financialization of food? Am. J. Agric. Econ. 99, 243–264 (2017).

Acknowledgements

An earlier version of this paper was circulated as “Extreme Dry Spells and Larger Storms in the U.S. Midwest Raise Crop Prices”. We thank comments by Michel Robe, Andrew Hultgren, Teresa Serra, Joe Janzen, Marc Pourroy, Scott Irwin, Todd Hubbs, Haibo Jiang, Peyton Ferrier, four anonymous reviewers and presentation attendees at the Commodities and Energy Market Meeting 2022, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign ACE, United States Department of Agriculture, Universidad de San Andrés, NCCC-134 2023 Meeting, Universidad de Buenos Aires, AAEP 2023, Red NIE 2023, 2023 Commodities Research Symposium at the University of Colorado Denver, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, AAEA 2024, LACEA 2024, Econometric Models of Climate Change VIII, and the University of Guelph.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.M. and M.C. conceptualized and designed the study and wrote the original draft. M.C., N.M. and E.M. collected and analyzed data. All authors edited and reviewed the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Sustainability thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Martina Grecequet. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cornejo, M., Merovich, E. & Merener, N. Hot dry spells and extreme rain increased corn and soybean prices in the United States Midwest. Commun. Sustain. 1, 17 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00016-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44458-025-00016-4