Abstract

This study investigates the fundamental diffuse scattering mechanisms from three typical building wall surfaces, conducting measurements and model parameterization at 28 GHz and two key FR3 frequencies (8 GHz and 12 GHz). A novel three-dimensional (3D) measurement procedure is proposed to capture comprehensive spatial characteristics, and its effectiveness in improving parameterization accuracy was verified using 28 GHz data. For parameterization, we developed a new method utilizing two dimensions of the high-bandwidth power delay profile-received power and delay spread-thereby fully leveraging the rich information provided by such measurements. Furthermore, we introduce the ER-BK hybrid model, which integrates the Beckmann-Kirchhoff (BK) model’s high accuracy and cross-frequency adaptability with the Effective Roughness (ER) model’s simplicity, applying it to the building surfaces. Our results show that diffuse scattering at 8 GHz and 12 GHz is highly similar, distinct from that at 28 GHz. A comparison revealed that the BK model provides a better fit for our FR3 measurement data. Crucially, we validated the angular generalization of the parameterized BK model using data from a different incident angle than the one used for fitting. The feasibility of the ER-BK hybrid model was also verified through simulation of the parameterized marble surface.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In future 6G networks, the FR2 band (24.25–71 GHz) and the FR3 band (7.125–24.25 GHz) have garnered significant attention from both academia and industry1,2. These two bands are particularly valued for their ability to address coverage, capacity, and deployment challenges in typical wireless scenarios. Additionally, they offer substantial advantages for emerging technologies, including non-terrestrial networks, reconfigurable intelligent surfaces, and integrated sensing and communications (ISAC)3,4.

Electromagnetic (EM) wave propagation mechanisms typically include free-space propagation, penetration, reflection, diffuse scattering, and diffraction5. Among these, research on diffuse scattering is essential for reliable propagation analysis, particularly in the field of ISAC, as the modeling of scattered waves plays a critical role in sensing applications6,7,8. In the sub-6 GHz band, diffuse scattering is negligible in most scenarios9,10. This holds true when the primary scatterers are building surfaces and relatively regular road surfaces, with minimal structural irregularities. However, in the FR2 and FR3 bands, which operate at higher frequencies, diffuse scattering effects become significantly more pronounced.

Diffuse scattering models have been extensively investigated through measurements and theoretical analysis. Full-wave simulations such as the finite-difference time-domain method, which is based on Maxwell’s equations, have been used to study diffuse scattering models11,12. The physical optics approximation (PO) has also been applied in the research of diffuse scattering models13. However, both methods require detailed parameters of the surface and involve a high computational complexity. The works in14 and15 proposed integrating an ER based diffuse scattering model into ray tracing algorithms. This concept was subsequently validated through multitudinous measurements in the millimeter-wave band16,17. Another well-known DS model is the Beckmann–Kirchhoff (BK) model, which is based on the Kirchhoff approximation. It can describe the diffuse scattering properties across frequency bands using only two parameters: the root-mean-square (RMS) height of surface roughness and the spatial irregularity known as the correlation length18. It performs well in the terahertz band5,19, however, its computational complexity is higher compared to the ER model.

Although existing studies have conducted measurements across multiple frequency bands and for various materials, there still exist a few limitations. First, to our best knowledge, few studies have explored diffuse scattering measurements in the FR3 band, and existing work lacks a robust integration of theoretical models and experimental data to evaluate the practical performance of diffuse scattering models in this frequency range. Second, most existing measurement efforts have focused only on measurements where the transmitter (Tx) and receiver (Rx) are in the same plane, resulting in a lack of acquisition of 3D spatial information of diffuse scattering. Third, existing parameterization methods only consider the angular spectrum of power, which fails to fully utilize high-bandwidth measurement data. Finally, the current ER model struggles with low accuracy, and the BK model suffers from high complexity; a new approach is therefore needed to enhance diffuse scattering simulations. Addressing these limitations, our study makes four key contributions.

-

We conduct measurements on three typical outdoor building surfaces at two representative frequencies in the FR3 band, namely 8 GHz and 12 GHz, along with the 28 GHz millimeter-wave frequency, and collect high-bandwidth power delay profile (PDP) data.

-

We propose a 3D measurement procedure to capture richer spatial information of diffuse scattering and carry out real-world measurements to verify the effectiveness of this procedure.

-

We propose a model parameterization method that combines the power angular spectrum and the delay spread angular spectrum to make full use of the high-bandwidth PDP data.

-

We propose an ER-BK hybrid model that leverages the simplicity of the ER model and the cross-frequency band characteristics of the BK model. The effectiveness of this method has been verified using our measurement data.

Method

Diffuse scattering models

First, the general diffuse scattering geometry is shown in Fig. 1. The incident wave \({\overrightarrow{E}}_{i}\) has a zenith angle θi and an azimuth angle π. The reflected wave \({\overrightarrow{E}}_{r}\) features a zenith angle θr = θi and an azimuth angle 0, whereas the scattered wave \({\overrightarrow{E}}_{s}\) has a zenith angle θs and an azimuth angle ϕs. Here, ψi and ψr denote the spatial angles between the scattered wave and incident wave directions, and between the scattered wave and reflected wave directions, respectively.

The diagram illustrates the incident \({(\vec{E}_i,\,\text{red})}\), reflected \({(\vec{E}_r,\,\text{blue})}\), and scattered \({(\vec{E}_s,\,\text{purple})}\) waves defined by their respective zenith \({(\theta)}\) and azimuth \({(\phi)}\) angles. Specifically, \({\theta_i}\), \({\theta_r}\), and \({\theta_s}\) represent the zenith angles, while \({\phi_s}\) denotes the scattering azimuth. The spatial angles \({\psi_i}\) and \({\psi_r}\) indicate the angular separation between the scattered wave and the incident or reflected directions, respectively.

a The raw PDP observed before calibration, where significant fake multipath components (highlighted by red rectangles) appear hundreds of nanoseconds after the peak due to system hardware response. b The calibrated PDP using the back-to-back method, showing the elimination of fake multipaths and a reduction in the noise floor. The red dashed line indicates the multipath extraction threshold (defined as the peak value minus 30 dB). Grey dots represent the original data samples, blue dots denote the filtered valid multipath components, and the vertical magenta dashed line marks the position of the peak power.

The ER model, one of the most widely-used diffuse scattering models, characterizes the diffuse scattering process through a two-step approach.

First, it calculates the proportion of diffuse scattering energy to incident energy. Using the energy conservation relationship, the ratio of the scattered power to the incident power can be obtained as follow15:

where Γ represents the smooth surface reflection coefficient, and ρ is the reflection reduction factor that can be estimated by 18,20:

where hrms represents the standard deviation of the surface protuberance height about the mean height, k = 2π/λ represents the wave number.

Second, energy-normalized diffuse scattering patterns can be described by empirical formulas, and there are several classic empirical formulas, including the Lambertian model, directive model, and backscattering lobe model. Each one represents a distinct physical scenario and accounts for different diffuse scattering patterns.

Directive model postulates that the primary energy concentration occurs along the specular reflection direction with a certain angular spread21. The angular distribution of the field intensity be expressed as14 :

Here, K is a constant depending on the amplitude of the impinging wave:

Substituting it into eq. (3), we can get:

where ri and rs denote the distances from the Tx antenna to the incident point and from the incident point to the Rx antenna, respectively. θi represents the incident angle. ψs is the angle between the diffuse scattering and the specular reflection directions. The parameter αR determines the beamwidth of the diffuse scattering pattern. As it decreases, the beamwidth expands, resulting in a more dispersed angular distribution of the scattered energy. FαR is the normalization factor, and is given by :

and

The backscattering lobe model extends the directive model by incorporating an additional term to account for backscattering effects. In practical scenarios where surfaces display significant irregularities (e.g., balconies or columns) and the incident angle approaches grazing incidence, diffuse scattering contributions become substantial near the incident direction. To address this, the model integrates a diffuse scattering lobe aligned with the incident direction. The formulation is expressed as follows15:

In this model, ψi denotes the angle between the scattered and incident directions, and ψR denotes that between the scattered direction and specular reflection direction, αi governs the width of the back lobe, while αR controls that of the forward lobe—with larger values for both parameters narrowing their respective lobes and concentrating scattered energy. Additionally, Λ, a distribution coefficient within the range Λ ∈ [0, 1], regulates the amplitude ratio between the forward and backscattering lobes; when Λ = 1, the model simplifies to the directive model, retaining only the forward lobe contribution.

The maximum amplitude ES0 is calculated by14 :

where

and

Compared to the ER model, the two most critical parameters in the BK model are the variance of surface height hrms and the surface correlation length T. The BK model assumes that the height distribution of the material surface follows a Gaussian profile18,22:

and the surface correlation function is also Gaussian, satisfying:

The primary distinction between the BK model and the ER model lies in the form of the diffuse scattering pattern. The diffuse scattering power distribution in the BK model can be expressed as18,22,23:

where θi and θs represent the zenith angles of the incident field and the scattered field, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 1.And

Besides, F in (14) is called the geometric factor, which can significantly affect the diffuse scattering pattern. The most classic geometric factor is the Beckmann geometric factor24:

In addition, there is the Ogilvy factor, which is calculated based on boundary conditions:

The ER model can simply describe the diffuse scattering effects of different types of surfaces. However, its empirical parameters, including S and α, are difficult to determine in practical applications. Even for the same surface, these parameters will change with the frequency of the incident wave and the incident angle. In contrast, the BK model computes scattering results across frequency bands and incident angles via physical calculations once its two parameters are determined. However, its algorithmic complexity remains a limitation.

It has been pointed out in ref. 25 that the ER model, such as the ER directive model, can be used to fit the BK model. Notably, the improved ER directive model is employed here, as the BK model’s scattering results do not always exhibit peak energy in the specular reflection direction. To achieve a better fit to the BK simulation results, we adjust the ER directive model by replacing the original variable ψs with a new variable \(\psi {\prime}\), which represents the angle between the scattering direction and the peak scattering power direction. This demonstrates that the ER model can accurately match the BK simulation results, significantly simplifying scattering calculations. Additionally, it enables efficient determination of cross-frequency scattering parameters in ray tracing.

Measurement campaign

We used a time domain channel sounding system based on National Instruments (NI) hardware to conduct the measurement campaign26. The system operates under a superheterodyne architecture with an intermediate frequency (IF) range of 8–12 GHz. With the addition of our up-converter, it can also output millimeter waves spanning from 27.5 to 29.5 GHz.

The baseband signal of this system is a Zadoff-Chu (ZC) sequence with a length of 65,535. It employs a field programmable gate array module for real-time signal processing. Leveraging the autocorrelation properties of the ZC sequence, the PDP of the channel can be obtained27,28, with a multipath time delay resolution of up to 0.65 ns. Synchronization between the Tx and Rx is achieved using two pre-synchronized rubidium atomic clocks.

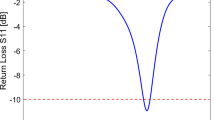

The PDP data directly obtained from the channel sounding system includes the hardware response of the system. When using such data, employing the widely accepted threshold (peak value of the PDP minus 30 dB) to get the filtered PDP data results in numerous fake multipath components that do not exist in reality (such as the multipaths appearing hundreds of nanoseconds after the peak in Fig. 2(a), corresponding to path lengths of tens to hundreds of meters, which do not exist in actual diffuse scattering meassurement with path of hundreds of meters).

To eliminate the hardware response, we employed a back-to-back calibration:

where hcal denotes the PDP after calibration, while hraw represents the raw PDP. The term G[K] is derived by directly connecting the Tx and Rx using a cable. After calibration, as Fig. 2(b) shows, the previously observed fake multipaths are shown to have disappeared, with a significant reduction in the noise floor.

After calibration, noise at the several-hundred-nanosecond mark may still appear above the threshold. To mitigate this risk, we have therefore added a 20 ns window around the peak, a setting that captures all multipaths within 6 meters while filtering out unreasonable noise points.

We conducted measurement campaigns on three types of building surfaces at the Minhang campus of Shanghai Jiao Tong University at 8 GHz, 12 GHz, and 28 GHz. The surfaces of the measured building walls are shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

The measurements used two tripod-mounted horn antennas at the Tx and Rx, respectively. Their technical specifications at 8 GHz, 12 GHz, and 28 GHz frequencies are detailed in Table 1. Four types of measurements were designed and conducted on the aforementioned three materials at the three carrier frequencies.

-

Tx and Rx antennas at the same height, incidence angle = 30°:

Table 1 Parameters of Experiment Setup Figure 5a depicts the measurement configuration with the Tx and Rx in the same plane, in which the Tx antenna is fixed at a height of 1.7 meters and positioned 1.5 meters from the center of the target wall surface (which is significantly greater than the Rayleigh distances of the antenna corresponding to each of the three frequencies, thereby ensuring the far-field condition is met for all test cases), oriented at a 30-degree angle relative to the normal direction. The Rx antenna is placed at the same height and distance from the center, and is systematically rotated in 10-degree increments.

-

Tx and Rx antennas at the same height, incidence angle ≠ 30°: To evaluate the generalization ability of our parameterized model under other incidence angles for the same surface, we performed measurements on marble and smooth wall surfaces with Tx angles of 40°, 50°, and 60°, and Rx angles fixed at 0° and the specular reflection direction, respectively.

-

Metal plate reflection measurement:

To verify the rationality of our measurement setup and simulation method, we conducted measurements on the power-angle spectrum of metal plate reflections at the three frequencies, as shown in Fig. 4. Specifically, using the same measurement setup as illustrated in Fig. 5a—with an incidence angle of 30°, the Rx rotated in 10-degree increments, and electromagnetic wave absorbing materials placed on both sides to prevent scattering interference from areas other than the target wall—the only difference is that the target wall surface was replaced with a metal plate.

-

Tx and Rx antennas at different heights:

In addition, to provide more information for model parameterization from the measured data, as suggested in ref. 26, additional spatial angle measurements can be implemented. As Fig. 5b, we conduct the spatial angle measurements on the rough wall. For the measurement, the Tx antenna is fixed at a height of 1.7 meters in the horizontal plane, aligned with the center of the wall and at a 30-degree angle to the normal. The Rx antenna is adjusted to heights of 1.7 m, 1.8 m, 1.9 m, and 2.0 m, while moving along a circular path with a radius of 1.5 m, with a step size of 10 degrees for each measurement.

a Measurement setup in the horizontal plane (2D). The transmitter (Tx) is fixed at a height of 1.7 m and a distance of 1.5 m from the center with a 30° incidence angle, while the receiver (Rx) is rotated along the arc in 10° increments. b Measurement setup in a 3D scenario showing the spatial distribution of measurement points. The red arrow indicates the fixed Tx orientation, and the yellow arrows and dots represent the Rx positions located on arcs with 0.1 m vertical spacing.

The 3D plot visualizes the geometric configuration used in the simulation. The red dot represents the transmitter (Tx) antenna, and the green square denotes the receiver (Rx) antenna. The light blue plane corresponds to the reflection surface. Black lines trace the specular reflection paths, whereas purple lines illustrate the diffuse scattering components.

Simulation and parameterization

We conducted simulations of the measurement scenario based on the ray-tracing algorithm (as shown in Fig. 6). To enable the integration of different diffuse scattering models, we utilized a self-developed ray-tracing software. Parameters involed in ray tracing, such as the antenna’s gain and HPBW, are its actual parameters, which are provided in Table 1.

In the simulations, the multi-hop paths and the ray paths from ground reflection and diffuse scattering have minimal impact on the PDP. To demonstrate this, we compared the measured reflection power spectra of the metal plate at three frequencies with the simplified ray-tracing simulated power angle spectrum (considering only the specular reflection of the metal plate) and calculated the RMSE between them. The RMSE values for 8 GHz, 12 GHz, and 28 GHz are 5.41 dB, 4.89 dB, and 4.74 dB, respectively. Such small discrepancies between the simplified simulation results and the measured data indicate that, under our measurement setup, the energy of the PDP is primarily derived from first-order scattering and reflection on the target surface.

We parameterize the diffuse scattering model by minimizing the discrepancy between measured data and ray-tracing simulation results. The high-bandwidth PDP data, featuring a time resolution of 0.65 ns (equivalent to a multipath resolution of approximately 0.195 m), enables enhanced multipath characterization. Consequently, our parameterization process extends beyond conventional power angular spectrum analysis10,17, providing a more comprehensive framework than prior scattering model studies.

We integrate both the angular spectrum of the delay spread and the angular spectrum of power derived from the PDP of diffuse scattering measurement to fit the diffuse scattering model:

where:

The metric employed is the symmetric mean absolute percentage error (SMAPE), an accuracy measure based on percentage errors with both lower and upper bounds; a smaller value indicates higher model accuracy. It is widely used in assessing the performance of channel models29,30,31. Pkand \({\tau }_{{{\rm{RMS}}}_{k}}\) represent the received power and delay spread at each location in the measurement, while \({\hat{{\rm{P}}}}_{k}\) and \({\hat{\tau }}_{{{\rm{RMS}}}_{k}}\) denote the received power and delay spread at the corresponding locations in the simulated scenario. N stands for the number of measured locations; for example, in measurements where the Tx and Rx are in the same plane, N = 16. A key advantage of SMAPE is that it allows the fitting accuracy of different parameters (i.e., power and delay spread) to be compared collectively. Combining the simplicity of the ER model and the accuracy of the BK model in prediction across frequency bands and under arbitrary incident angles, we propose the ER-BK hybrid diffuse scattering model.

-

Get parameters for BK model (T and hrms): First, we acquire the two parameters T and hrms of the surface in accordance with the measurement and parameterization scheme we proposed above.

-

Simulation based on BK model: Second, based on these two acquired parameters, we perform simulations of the BK model for the target frequency to obtain diffuse scattering patterns at different angles within this frequency band.

-

Fit simulation result with ER model: Third, we use the modified ER Directive model to fit the simulation results of the BK model, so as to obtain the three empirical parameters S, α, and θp (angle of the peak of the diffuse scattering power) of the ER Directive model under the desired frequency and different incident angles.

Results

Effectiveness of 3D Rx measurements for parameterization of DS models

As an example, we use the 3D Rx measurement data to parameterize the 28 GHz backscattering lobe model. In traditional parameterization processes17,32,33, only the RT results within the incident plane are considered for fitting the measured data to determine the diffuse scattering model parameters, as demonstrated previously. This fitting process overlooks the changes caused by the spatial distribution of diffuse scattering power. To address this, under rough wall measurement conditions, we varied the height of Rx by Δh, integrated the obtained data, and then applied the fitting process described above.

The received power at various 3D positions is illustrated in Fig. 7, where the blue circles represent the results of the ray tracing with the best parameters using data only in the incident plane (Δh = 0 cm), the red dots represent the results of the ray tracing with the best parameters at four Rx heights (Δh = 0, 10, 20, 30 cm), and the colored surface represents the measured data. As the Rx height increases, it can be observed that the diffuse scattering model determined based on the incident plane (S = 0.60, αR = 1, αi = 10, Λ = 0.2) incorrectly predicts the actual backscattering power outside the plane. On the other hand, by fitting the data obtained from multiple stereoscopic positions, the scattering model (S = 0.42, αR = 6, αi = 4, Λ = 0.2) can partially correct this error while still maintaining a good fitting performance within the incident plane. This indicates that for a more accurate and detailed analysis of diffuse scattering effects, it is necessary to consider the diffuse scattering effects in the stereoscopic space, within an acceptable level of complexity, to jointly determine the actual diffuse scattering model parameters.

The 3D plot displays the received power distribution relative to the azimuth angle and receiver height variation \({(\Delta {h})}\). The colored surface represents the actual measured data. Blue circles denote the ray tracing simulation results using diffuse scattering parameters fitted exclusively from data within the incident plane \({(\Delta h = 0\,\text{cm})}\). Red dots indicate the simulation results utilizing parameters fitted from data collected at four different receiver heights \({(\Delta h = 0, 10, 20, 30\,\text{cm})}\).

Material and frequency dependence of diffuse scattering effect among 8 GHz, 12 GHz and 28 GHz

Figure 8a–f show the angular power spectrum and delay spread spectrum of three material surfaces at the three frequencies. It can be first observed that the type of material has a significant impact on both the power angular spectrum and the delay spread angular spectrum. Regarding the influence of frequency, as shown in Fig. 8a–c, the received power of these three materials at the three frequencies is all concentrated in the specular reflection direction, exhibiting a certain degree of angular broadening. Moreover, compared with the power angular spectrum at 28 GHz, those at 8 GHz and 12 GHz show obvious similarity. Specifically, the received power at 8 GHz and 12 GHz is much stronger than that at 28 GHz. Figure 8d–f indicate that, at all three frequencies, the angular spread of PDP is more pronounced in the incident plane. In addition, the delay spread at 28 GHz is quite different from (much larger than) that at the other two frequencies. However, for the two frequencies in the FR3 band, the change from 8 GHz to 12 GHz has minimal impact on the scattering power and delay spread. So, in the subsequent discussion on the fitting performance of the scattering model for the FR3 band, we only present the fitting results from the 8 GHz scattering measurement.

Fitting results using ER and BK models

We fitted the received power angular spectrum and delay spread angular spectrum data for the three material at 8 GHz using both the ER model and the BK model (using planar data for marble walls and smooth walls, and data from four receiver heights for brick walls).

For the brick wall, the backscattering lobe model within the ER model was employed. Figures 9 and 10, respectively, present the best fitting results of two parameters, received power and delay spread, under the ER and BK models for three materials, while Table 2 presents the parameters of the two scattering models for the three surfaces. It is evident that when simultaneously considering the energy angular spectrum and the delay spread angular spectrum, the ER model does not fit the measurement data well, whereas the BK model demonstrates better adaptability in fitting both the energy spectrum and the delay spectrum.

a–f, The fitting performance for the marble wall (a, b), smooth wall (c, d), and brick wall (e, f). The left column (a, c, e) displays the results using the Effective Roughness (ER) model, while the right column (b, d, f) corresponds to the Directive Scattering (BK) model. Red dots represent the measured power data. The blue, cyan, and green solid lines denote the simulated total power, specular reflection power, and diffuse scattering power, respectively.

a–f The fitting performance for the marble wall (a, b) smooth wall (c, d) and brick wall (e, f). The left column (a, c, e) displays the results using the Effective Roughness (ER) model, while the right column (b, d, f) corresponds to the Directive Scattering (BK) model. Red dots represent the measured delay spread data, and the blue solid lines denote the simulated delay spread.

Evaluation of the generalization capability of the parameterized model under different incidence angles

The parameterized BK model is capable of predicting the angle spectrum of received power under arbitrary incidence angles. Using the aforementioned parameterized BK model, scattering simulations were performed for two types of surfaces (marble and smooth wall) at two frequencies (8 GHz and 12 GHz) with incidence angles of 40°, 50°, and 60°. As illustrated in Fig. 11, a comparison between the simulated results and the measured power values shows that the model parameters fitted under the 30° incidence angle can effectively predict the scattering power under other incidence angles. This shows that the model, parameterized using measured data from a single incidence angle, can be generalized to scenarios involving other incidence angles.

The figure compares the measured and predicted received power for the marble wall and the smooth wall at frequencies of 8 GHz and 12 GHz. The model predictions for incidence angles of 40°, 50°, and 60° utilize parameters fitted exclusively from data collected at a 30° incidence angle. Solid and hatched blue bars represent the measured power at the receiver angle of 0° and the specular reflection direction, respectively. Solid and dashed pink outlines denote the corresponding predicted power values generated by the model.

Parameterization results of the ER-BK hybrid model

Following the ER-BK hybrid model introduced in Section before, we conducted BK model simulations at 28 GHz using the BK model fitting parameters derived from the above 8 GHz measurement data. Figure 12 shows the BK scattering patterns of marble material and the corresponding parameter fitting results of the improved ER model under three incident angles (20°, 40°, 60°, and 80°) at 28 GHz.

First, it can be observed that in our proposed method, the improved ER model can effectively fit the simulated scattering patterns of the BK model. Second, we can observe the variation patterns of some parameters of the ER model with the incident angle. It can be seen that the larger the incident angle, the smaller the scattering coefficient S, which is consistent with the conventional ER model. Meanwhile, beamwidth α increases as the incident angle becomes larger, meaning that the lobe widens with the increase of the incident angle. This is a phenomenon that cannot be described by the traditional ER model. One plausible physical mechanism behind it is that as the incident angle increases, the illuminated area expands; this causes the phase of electromagnetic waves to become more disordered after interacting with the surface, ultimately leading to a more dispersed spatial distribution of the waves.

Discussion

In this study, we investigate diffuse scattering mechanisms across centimeter-wave and millimeter-wave bands, performing measurements and model parameterization on three typical building wall surfaces. measurements cover the 28 GHz millimeter-wave frequency and two frequencies within the FR3 band (8 GHz and 12 GHz). Specifically, we propose three key improvements for building surface scattering measurement and modeling: Firstly, we introduce a 3D measurement scheme to capture spatial scattering data. This enables the extraction of comprehensive spatial scattering information, a significant enhancement over the limitations of traditional 2D angular measurements10,17,32. Secondly, we utilize a parameterization approach based on total power and delay spread from high-bandwidth PDP. In contrast to conventional methods that rely only on fitting the angular power spectrum (e.g.,15,17,33), our technique exploits the full temporal richness of high-bandwidth PDPs to derive more accurate model parameters. Finally, we introduce an ER-BK hybrid model that integrates the accuracy of the BK model and the simplicity of the ER model, thereby offering a novel and balanced approach to surface scattering modeling.

Our results yield several insights: First, the 3D measurement scheme is validated to enhance parameterization accuracy, confirming its effectiveness in capturing spatial scattering features. Second, diffuse scattering characteristics at 8 GHz and 12 GHz are found to be highly similar, which carries important implications for FR3 band channel modeling—it may support the development of a unified or simplified model framework for this frequency range, reducing modeling complexity. Third, the BK model demonstrates superior fitting performance for FR3 band data, and notably, models parameterized under a single incident angle exhibit good generalization ability for predicting scattering at other angles, simplifying the parameterization process. Finally, the ER-BK hybrid model proves feasible for simulating parameterized surfaces, balancing accuracy and computational efficiency.

However, this work still has two limitations: First, environmental factors (e.g., temperature, humidity) were not considered in scattering parameterization, which are critical for real-world applicability. Second, the computational complexity of the existing model remains non-trivial, posing challenges for efficient deployment in large-scale scenarios. Corresponding future research directions address these limitations: First, conduct measurements on surfaces under different environments (e.g., humidity), investigate the impact of environmental factors, and incorporate them into the model. Second, introduce AI-driven methods to improve modeling efficiency and accuracy, or develop hybrid physics-data models that combine physical interpretability with data-driven fitting capability, further boosting modeling performance.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study consist of channel measurement data (Power Delay Profiles) collected at 8 GHz, 12 GHz, and 28 GHz frequencies.

References

Bazzi, A. et al. Upper mid-band spectrum for 6G: vision, opportunity and challenges. (IEEE Communications Magazine, 2025).

Shakya, D. et al. Comprehensive FR1 (c) and FR3 lower and upper mid-band propagation and material penetration loss measurements and channel models in an indoor environment for 5G and 6G. In Proc. IEEE Open Journal of the Communications Society (IEEE, 2024).

Chen, W. et al. 5G-advanced toward 6G: past, present, and future. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 41, 1592–1619 (2023).

Cui, Z., Zhang, P. & Pollin, S. 6G wireless communications in 7–24 GHz band: opportunities, techniques, and challenges. In 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Dynamic Spectrum Access Networks (DySPAN), London, United Kingdom, 2025, pp. 1-8.

Han, C., Bicen, A. O. & Akyildiz, I. F. Multi-ray channel modeling and wideband characterization for wireless communications in the terahertz band. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 14, 2402–2412 (2014).

Yaman, Y. & Spasojevic, P. A ray-tracing intracluster model with diffuse scattering for mmwave communications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 20, 653–657 (2021).

Zhao, Y. et al. Sensing-assisted predictive beamforming with multipath echo signals. IEEE Transact. Veh. Technol. 74, 7539–7553 (2025).

Reddy, V. A. et al. Fundamental performance limits of mm-wave cooperative localization in linear topologies. IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett. 9, 1899–1903 (2020).

Taleb, F., Hernandez-Cardoso, G. G., Castro-Camus, E. & Koch, M. Transmission, reflection, and scattering characterization of building materials for indoor THZ communications. IEEE Trans. Terahertz Sci. Technol. 13, 421–430 (2023).

Ju, S. et al. Scattering mechanisms and modeling for terahertz wireless communications. In Proc. ICC 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC), 1–7 (IEEE, 2019).

Yi, H. et al. Full-wave simulation and scattering modeling for terahertz communications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 17, 713–728 (2023).

Xie, P. et al. Terahertz wave propagation characteristics on rough surfaces based on full-wave simulations. Radio Sci. 57, 1–16 (2022).

Hanpinitsak, P. et al. Frequency characteristics of geometry-based clusters in indoor hall environment at SHF bands. IEEE Access 7, 75420–75433 (2019).

Degli-Esposti, V., Guiducci, D., de’Marsi, A., Azzi, P. & Fuschini, F. An advanced field prediction model including diffuse scattering. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 52, 1717–1728 (2004).

Degli-Esposti, V., Fuschini, F., Vitucci, E. M. & Falciasecca, G. Measurement and modelling of scattering from buildings. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 55, 143–153 (2007).

Ren, M.-H. et al. Diffuse scattering directive model parameterization method for construction materials at mmwave frequencies. Int. J. Antennas Propag. 2020, 1583854 (2020).

Pascual-Garcia, J., Molina-García-Pardo, J.-M., Martinez-Ingles, M.-T., Rodriguez, J.-V. & Saurin-Serrano, N. On the importance of diffuse scattering model parameterization in indoor wireless channels at mm-wave frequencies. IEEE Access 4, 688–701 (2016).

Beckmann, P. & Spizzichino, A. The scattering of electromagnetic waves from rough surfaces. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2043–2050 (IEEE, 1987).

Das, S. et al. Ambit-process based channel model for urban microcellular communication at 140 GHz. IEEE Trans. Wireless Commun. 23, 3959–3974 (2023).

Boithias, L. & Beeson, D. Radio Wave Propagation (McGraw-Hill,1987).

Vitucci, E. M., Cenni, N., Fuschini, F. & Degli-Esposti, V. A reciprocal heuristic model for diffuse scattering from walls and surfaces. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 71, 6072–6083 (2023).

Tsang, L., Kong, J. A. & Ding, K.-H. Scattering of Electromagnetic Waves: Theories and Applications (John Wiley & Sons, 2000).

Vernold, C. L. & Harvey, J. E. Modified Beckmann-Kirchoff scattering theory for nonparaxial angles. In Proc. Scattering and Surface Roughness II, vol. 3426, 51–56 (SPIE, 1998).

Ragheb, H. & Hancock, E. R. The modified Beckmann–Kirchhoff scattering theory for rough surface analysis. Pattern Recognit. 40, 2004–2020 (2007).

Hanpinitsak, P., Dan, Q., Keerativoranan, N., Saito, K. & Takada, J.-I. Comparison of different diffuse scattering models on random rough surface based on common outdoor materials at 28 GHz band. In Proc. IEEE Antennas and Wireless Propagation Letters (IEEE, 2025).

Guo, Y., Zhang, T., Sun, S., Tao, M. & Gao, R. Measurement and analysis of scattering from building surfaces at millimeter-wave frequency. In Proc. IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference, 2025 (IEEE, 2025).

Sun, S. et al. “Modeling and analysis of land-to-ship maritime wireless channels at 5.8 GHz,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, https://doi.org/10.1109/TWC.2025.3634176 (2025).

Mao, K. et al. A UAV-aided real-time channel sounder for highly dynamic nonstationary A2G scenarios. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 72, 1–15 (2023).

Hoydis, J. et al. Learning radio environments by differentiable ray tracing. In Proc. IEEE Transactions on Machine Learning in Communications and Networking (IEEE, 2024).

Wang, S. et al. Deep learning-based vehicular millimeter-wave channel prediction using visual information. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 24, 2332–2336 (2025).

Chen, J. et al. From similarity to superiority: channel clustering for time series forecasting. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 37, 130635–130663 (2024).

Guo, G., Yang, X., Zhou, Y. & Ma, N. Diffuse scattering analysis of indoor propagation channel at terahertz frequency. In Proc. IEEE Wireless Communications and Networking Conference (WCNC), 1–6 (IEEE, 2024).

Tian, H. et al. Effect level based parameterization method for diffuse scattering models at millimeter-wave frequencies. IEEE Access 7, 93286–93293 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grants 62271310, 62431014, 62125108, 62271250, and 62571276. We would also like to express our sincere gratitude to Mr. Yulu Guo from Shanghai Jiao Tong University for his invaluable help and technical support during the diffuse scattering measurement campaign. His support in the measurement setup and data collection was essential to this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z. conducted measurements, wrote the main manuscript text, and prepared all the figures. S.S designed the study, developed research methods, wrote the main manuscript text, and secured financial support. M.T. supervised the project and secured financial support. T.Z., S.S., M.T., Q.Z. and R.G. reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, T., Sun, S., Tao, M. et al. Diffuse scattering measurements and mechanism analysis at 8, 12, and 28 GHz for typical building surfaces. npj Wirel. Technol. 2, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44459-025-00016-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44459-025-00016-9