Key Points

-

Appliances returned from laboratories are often contaminated with bacteria.

-

Infection control should not be left to the laboratory but the clinician treating the patient.

-

A policy detailing the responsibility of the dental team in the control of infection from laboratories is advisable.

Abstract

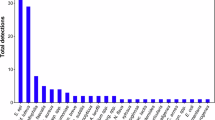

Decontamination of dental instruments has recently been the subject of considerable debate. However, little information is available on the potential bacterial colonisation of dental appliances returning from dental laboratories and their need for decontamination. This study investigated the extent and nature of microbial contamination of removable prosthodontic appliances produced at different dental laboratories and stored in two clinical teaching units (CTU 1 and CTU 2) of a dental hospital and school. Forty consecutive dental prosthodontic appliances that were being stored under varying conditions in the two clinical teaching units were selected for study; the appliances having been produced 'in-house' (hospital laboratory) or 'out-of-house' (external commercial laboratory). Two appliances, that were known to have undergone decontamination before storage, were used as controls. Swabs were taken according to a standard protocol and transferred to the microbiological laboratory with bacterial growth expressed as colony forming units (cfu) per cm2. Microbial sampling yielded growth from 23 (58%) of the 40 appliances studied (CTU 1, n = 22; CTU 2, n = 18), with 38% of these having a high level of contamination (>42,000 cfu/cm2). The predominant bacteria isolated were Bacillus spp. (57%), pseudomonads (22%) and staphylococci (13%). Fungi of the genus Candida were detected in 38% of the samples. There was no significant difference in contamination of the appliances in relation to either their place of production or the CTU (p >0.05). However, the level of contamination was significantly higher (p = 0.035) for those appliances stored in plastic bag with fluid (n = 16) compared to those stored on models (n = 19). No growth was recovered from the two appliances that had undergone decontamination before storage. The research showed that appliances received from laboratories are often contaminated and therefore there is a need for routine disinfection of such items before use and a review of storage conditions required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

British Dental Association. Advice sheet A12: Infection control in dentistry. Available at: http://universitydental.co.uk/resources/bda-cross-infection.pdf. Accessed 16 August 2011.

EC Medical Devices Directive No 10. Guidelines to medical Devices Directive 93/42/EEC for manufacture of custom made devices. Dublin: Department of Health and Children, 1997.

Chau V B, Saunders T R, Pimsler M, Elfring D R . In-depth disinfection of acrylic resins. J Prosthet Dent 1995; 74: 309–313.

Katberg J W Jr. Cross-contamination via the prosthodontic laboratory. J Prosthet Dent 1974; 32: 412–419.

Rudd R W, Senia, S E, McCleskey F K, Adams E D . Sterilization of complete dentures with sodium hyperchlorite. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 51: 318–321.

Wakefield C. Laboratory contamination of dental prostheses. J Prosthet Dent 1980; 44: 143–146.

Pavarina A C, Pizzolitto A C, Machado A L et al. An infection control protocol: effectiveness of immersion solutions to reduce the microbial growth on dental prostheses. J Oral Rehabil 2003; 30: 532–536.

Backenstose W, Wells J G . Side effects of immersion-type cleansers on the metal components of dentures. J Prosthet Dent 1977; 37: 615–621.

Langwell W. Cleansing of artificial dentures. Br Dent J 1955; 99: 337–339.

Neill D. A Study of materials and methods employed in cleaning dentures. Br Dent J 1968; 124: 107–115.

Molinari J A, Merchant V A, Gleason M J. Controversies in infection control. Dent Clin North Am 1990; 34: 55–69.

Gordon B L, Burke F J T, Bagg J, Marlborough H S, McHugh E S . Systematic review of adherence to infection control guidelines in dentistry. J Dent 2001; 29: 509–516.

Kilfeather G P, Lynch C D, Sloan A J, Youngson C C . Quality of communication and master impressions for the fabrication of cobalt chromium removable partial dentures in general practice in England, Ireland and Wales in 2009. J Oral Rehabil 2010; 37: 300–305.

Jagger D C, Huggett R, Harrison A . Cross-infection control in dental laboratories. Br Dent J 1995; 179: 93–96.

Henderson C W, Schwartz R S, Herbold E T, Mayhew R B . Evaluation of the barrier system: an infection control system for the dental laboratory. J Prosthet Dent 1987; 58: 517–521.

Larato D C. Disinfection of pumice. J Prosthet Dent 1967; 18: 534–535.

Verran J, Kossar S, McCord J F . Microbiological study of selected risk areas in dental technology laboratories. J Dent 1996; 24: 77–80.

Verran J, Winder C, McCord J F, Maryan C J . Pumice slurry as a cross infection hazard in nonclinical (teaching) dental technology laboratories. Int J Prosthodont 1997; 10: 283–286.

Williams H N Jr, Falkler W A, Hasler J F, Libonati J P . The recovery and significance of nonoral opportunistic pathogenic bacteria in dental laboratory pumice. J Prosthet Dent 1985; 54: 725–730.

Witt S, Hart P . Cross-infection hazards associated with the use of pumice in dental laboratories. J Dent 1990; 18: 281–283.

Dental Protection Limited. Update on infection control. SADJ 1999; 54: 641–643.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, D., Chamary, N., Lewis, M. et al. Microbial contamination of removable prosthodontic appliances from laboratories and impact of clinical storage. Br Dent J 211, 163–166 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.675

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bdj.2011.675