Abstract

The notion of animal culture, defined as socially transmitted community-specific behaviour patterns, remains controversial, notably because the definition relies on surface behaviours without addressing underlying cognitive processes. In contrast, human cultures are the product of socially acquired ideas that shape how individuals interact with their environment. We conducted field experiments with two culturally distinct chimpanzee communities in Uganda, which revealed significant differences in how individuals considered the affording parts of an experimentally provided tool to extract honey from a standardised cavity. Firstly, individuals of the two communities found different functional parts of the tool salient, suggesting that they experienced a cultural bias in their cognition. Secondly, when the alternative function was made more salient, chimpanzees were unable to learn it, suggesting that prior cultural background can interfere with new learning. Culture appears to shape how chimpanzees see the world, suggesting that a cognitive component underlies the observed behavioural patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reports of large-scale community-specific behavioural differences in wild chimpanzees have led to the provocative hypothesis that there is no fundamental difference in kind between chimpanzee and human cultures1,2,3,4,5. This conclusion has remained highly controversial, for both empirical and theoretical reasons. The claim is largely based on a systematic analysis of over 150 years of observational data from seven long-term chimpanzee field sites, but this research has sometimes been dismissed as mere “discussions”6,7 rather than direct evidence for culture in chimpanzees. Although the community-specific behavioural diversity in chimpanzees is generally accepted, sceptics continue to argue that this diversity could be the product of individual trial-and-error learning in response to the specific ecological conditions present at the different field sites. If this were the case, then this community-specific behavioural diversity would not qualify as ‘cultural’ in the human sense and the two phenomena would merely be analogous6,8,9. For instance, some authors have claimed that an infant chimpanzee observing how wind can shift vegetation and expose ants may learn as much as if it had witnessed its mother doing so and subsequently develop the behaviour on its own through a learning mechanism called ‘emulation’10,11. If such reasoning was true, it would have to be concluded that social variables are irrelevant. Although the term ‘emulation’ has been used in other ways since first proposed by Tomasello and colleagues12, the key point is that animals may simply learn to reproduce the result of an action rather than the action itself8,11. Additionally, the way this phenomenon may occur appears to grant a key role to the ecological surroundings in generating the learning of novel behaviours. For instance, Tennie al.8 state that “nut crackers and termite fishers leave their tools and detritus behind and in the right place, which makes the learning of their offspring and others much easier” (p. 2406). Emulation has been investigated extensively in captivity, notably through so-called ‘ghost’ experiments, in which the novel behaviour is demonstrated without any relevant social input and in some cases this has been sufficient for chimpanzees to learn novel behaviours13,14. However, in some other experiments involving complex tool use, learning was not observed, which was attributed to the absence of a social model15.

What social learning mechanism chimpanzees rely on in the wild is unknown. In current discussions, the consensus is that chimpanzees have access to a range of learning mechanisms, including emulation and imitation16. Others have argued that there is no strong dichotomy between individual and social learning but that both mechanisms are necessary in the acquisition of cultural behaviours, as addressed by the master-apprentice17 or the hybrid-learning18 models. Tennie et al.'s model8 suggests that the acquisition of novel behaviours is influenced by what individuals encounter in their environment, notably artefacts left behind by other individuals, but that demonstration is not necessary. According to this view the ecological settings or ‘affordances’ (defined as "physical properties of objects and of relationships among objects”19) may be enough to select for behaviours used by a chimpanzee to deal with a task. In recent experiments, however, we found that different Ugandan chimpanzee communities of the same subspecies, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, reacted differently to the same apparatus, a rectangular-shaped cavity drilled into a fallen horizontal log that was filled with liquid honey. Individuals of the Sonso community of Budongo Forest probed the cavity with their fingers or manufactured leaf-sponges to use as probes while individuals of the Kanyawara community of Kibale National Park manufactured sticks to extract the honey20. These results thus suggest that chimpanzee behaviour is not just driven by the affordances of a task. Results were more consistent with the hypothesis that community-specific tool choices are the result of pre-existing cultural differences in tool use behaviour21. Additionally, we found that chimpanzees in the two communities differed in their propensity to resort to tool use: in Kanyawara, only 3 of 17 individuals tested did not manufacture a stick to access honey, while in Sonso only 4 of 24 manufactured a leaf-sponge. Although manufacturing a tool was not required in the first experiment as most honey was accessible with fingers, it was mandatory in the second experiment (obligatory condition), as the honey was too far to reach with fingers. Nonetheless, only 2 Sonso individuals who participated in this experiment produced a tool (a leaf-sponge); the 9 others remained unsuccessful.

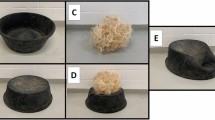

Here, we investigated if chimpanzees confronted with a novel task perceive an artificially provided tool in community-specific ways, i.e. whether individuals evaluate the tool's affordances in relation to the task through a cultural filter. To address this question, we presented members of the Sonso and Kanyawara community with the same task, liquid honey trapped in a rectangular-shaped hole. In the critical test condition, we provided a suitable tool next to the hole, a 40 cm branch of an Alstonia shrub, with all leaves removed for half of its length (fig. 1). We were interested in which parts of the tool chimpanzees of the two communities would find suitable to solve the problem. According to Tennie et al.'s model, chimpanzees should react in a species-specific way, as the tools provided and their affordances, were identical in both communities. According to our previous findings20, chimpanzees should react in a community-specific way, as their assessment of the tool would be biased by their community-specific knowledge.

In a second experiment, we exposed members of the Sonso community to the solution preferred by the Kanyawara individuals, i.e. by letting them encounter and retrieve the leafy stick directly from the hole, as many of them had still not found a tool-based solution to the honey trap problem. This way, individuals were able to experience directly the physical action of stick use. In 20 years of observations, no Sonso chimpanzee has ever been observed to use a stick in foraging related contexts, although leaf-sponges are fabricated routinely to access water from cavities22. This second experiment thus addressed the question of whether chimpanzee will learn a novel behaviour if induced to execute it and, by doing so, to solve the problem on their own.

Results

Baseline

Although Kanyawara individuals engaged somewhat longer with the apparatus, there was no significant difference in engagement time between Sonso and Kanyawara individuals, suggesting that performance differences could not be ascribed to differences in motivation (NKanyawara = 14, NSonso = 29, Mann-Whitney test, U = 130 p = 0.058, excluding QT in Kanyawara as an outlier; table 1 and figure 2). N = 29 chimpanzees of the Sonso community engaged in one or both experiments, but no one used or produced a stick to access the honey although N = 7 manufactured leaf-sponges (2009 study: N = 4; this study: N = 3). The remaining individuals did not produce any tools at all and were thus largely unable to access the honey. The fact that Kanyawara chimpanzees showed a trend towards longer engagement time was probably due to the fact that they were more successful in extracting honey than the Sonso individuals, who abandoned the apparatus earlier (figure 2).

Experiment 1: Provisioning of the leafy stick

In Sonso, 21 individuals participated in the experiment (table 1). Three of 21 (14.3%) seized the leafy stick we had provided. All proceeded to detach the leaves with their lips, discard the stick and roll the leaves in their mouths to produce a sponge (see video 1). The remaining 18 individuals ignored the leafy stick, but two of these (11.1%) manufactured a leaf-sponge from the surrounding vegetation.

In Kanyawara, 12 individuals participated in the experiment (table 1). 5 of 12 (41.7%) seized the leafy stick and all 5 proceeded to insert the bare end of the stick to acquire the honey (see video 2). 3 of 5 removed and discarded the leafy part from the stick before inserting it but none manufactured a leaf sponge. The remaining 7 individuals ignored the tool but 4 of these (57.1%) manufactured a stick tool from the surrounding vegetation.

Experiment 2: Highlighting the dipping function of the leafy stick (Sonso only)

20 Sonso individuals participated in the experiment in at least one of the conditions. The shared feature of this experiment was that the leafy stick was already inserted into the cavity when individuals arrived at the apparatus, thus making its functional potential as a dipping tool most salient. 15 of 20 individuals (75.0%) interacted with the leafy stick, but none used the tool to extract honey. Two individuals simply touched the leafy stick but did not retrieve it; three individuals grabbed and retrieved the leafy stick but then discarded it without further signs of interest. 10 removed the leafy stick to engage with the honey-covered part (smell: 6 of 10; consume: 4 of 10; table 2). All individuals subsequently discarded the leafy stick and none used it as a dipping tool. Finally, 5 of the 20 individuals ignored the leafy stick completely, but instead inserted one of their hands into the hole. After these initial interactions, 19 of 20 individuals continued to probe (unsuccessfully) with their hands, or they simply walked away. One individual manufactured a leaf-sponge and succeeded to extract honey.

In sum, although we presented the leafy stick in a way that revealed its functional properties in retrieving honey, either as a brush or as a dipping tool, all the Sonso chimpanzees who engaged in the experiment, including those who (accidentally) obtained honey by removing the leafy stick from the hole, failed to use it in these configurations. None of the non-tool using individuals discovered any of the three possible functions of the ‘leafy stick’ (sponging, brushing, dipping) and thus remained unsuccessful in their attempts to obtain honey. None of the leaf-spongers took advantage of the tool's two alternative functions.

Discussion

Our results are relevant to the study of chimpanzee cognition and culture and the links between the two phenomena. Experiment 1 shows that chimpanzees of two different communities with different (presumed) cultural backgrounds1 react differently to the affordances of an experimentally provided multi-functional tool. The stick-using Kanyawara chimpanzees found the stick part of the leafy stick most salient and useful to extract honey, while the non stick-using Sonso chimpanzees found the leafy part of the exact same tool most salient. Different communities of wild chimpanzees can thus react in radically different ways to the same features of their environment. This suggests that they may perceive and interpret their environment in different ways, notably in relation to their cultural knowledge. Similarly to our previous study20, the segregation of the behaviours chosen by the different communities was complete with no overlap. Chimpanzees at Kanyawara found the stick part of the tool the most salient, using it as a dipping device but ignoring the potential brushing and sponging possibilities. This was further illustrated by the behaviour of three individuals who removed and discarded all leaves from the leafy stick before inserting it into the honey. In contrast, the three chimpanzees at Sonso who engaged with the leafy stick focused on its leafy part, which was used to produce a leaf sponge to extract honey. In contrast, the wooden part of the tool was discarded. Out of the three, only one had already used a leaf-sponge in the baseline condition. The two new leaf-spongers had previously engaged with the apparatus (2009 experiment, obligatory condition) but had not produced any tool before. Although in one case, it may be due to the limited exposure to the apparatus the juvenile (KA) had during the baseline condition, it is less clear in the case of JT. A greater motivation to access the honey during this new session may explain why she manufactured a tool this time.

Generally, there was a trend for Kanyawara chimpanzees to engage longer with the apparatus than Sonso chimpanzees. However, we do not think that this is due to a difference in motivation to obtain honey, because successful tool-users at Sonso spent as much time engaging with the apparatus as successful tool-users at Kanyawara (table 1). Thus, the overall lower engagement time at Sonso is probably due to the numerous individuals who were unable to transfer their general leaf-sponging abilities to the problem at hand, which led them to abandon the apparatus more quickly than others. At Kanyawara, most individuals came up with a stick solution and success rates were thus much higher. In conclusion, wild chimpanzees appear to assess the functional properties of tools in community-specific ways, suggesting that cultural knowledge may impact on the way they comprehend their environment.

In experiment 2, we focused on the Sonso chimpanzees and exposed them to the technique used by the Kanyawara chimpanzees. This community was interesting for two reasons. Firstly, only seven of 29 individuals who engaged with the apparatus in this and the 2009 experiment came up with a tool solution, suggesting that transferring their general leaf-sponging skills to this problem was not an easy or automatic process. The same pattern was seen in experiment 1 where only two additional individuals used leaf-sponges to access the honey. Secondly, although 20 individuals showed much interest in the apparatus and engaged to different degrees with the leafy stick, none discovered the dipping or brushing functions of the tool. Therefore, these results do not support the idea that chimpanzees can learn tool use easily through affordance learning8,11, even if the functional properties are made highly conspicuous.

Our results suggest that previous experience may mediate what types of tools wild chimpanzees use in novel situations and perhaps more information, notably in terms of socially mediated input, may be needed before a novel tool behaviour can be learned. These findings are in line with research in captivity, which has shown that apes prefer to rely on previously acquired foraging techniques, with no evidence for modifications to improve efficiency, a phenomenon named ‘conservatism’23,24. However, observations in the wild suggest that chimpanzees can also adapt and modify an existing foraging technique, ant-fishing in trees, to some degree25. Why did the Sonso chimpanzees not discover the dipping behaviour? A first hypothesis is that they simply needed more exposure to the problem. In experiment 2, most individuals only received 1 or 2 exposures, but never more than 4, suggesting that more exposure may be necessary. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that the behaviour has already been present in the community, but that individuals need extended exposure to activate it. However, the point of our experiment was to address whether novel behaviour appears directly in response to favourable affordances, as proposed by Tennie et al.8. In this case, limited exposure is the natural condition because it is very unlikely that chimpanzees will encounter sticks protruding from beehives, a key condition for affordance learning. Our results, thus, do not support Tennie et al.'s8 model of how chimpanzees acquire tool use in the wild.

As outlined earlier, our data do not suggest that the Sonso chimpanzees' failure to acquire adequate tool use was due to a lack of motivation. Various additional observations also argue against a motivational account. Some individuals retrieved the stick and even licked the honey from it (NB), but they subsequently tried to access the honey with their hands without success. Another possible explanation for the lack of success is based on the notion of a sensitive phase. Perhaps the tested individuals did not develop tool use because they were simply too old26. This is not so likely because our sample of tested individuals ranged from young juveniles (e.g. NT) to old adults (e.g. NB), thus covering all ages. Finally, it is possible that several of the previously mentioned factors (sensitive phase, affordance learning, social settings) need to be present in combination. For example, it may be necessary for infant chimpanzees to encounter sticks left in cavities by their mothers and they may need to observe other group members performing actions associated with stick use in order to understand that sticks can be used as tools. There is evidence that more complicated tool use, such as termite fishing or nut cracking, are partly acquired by younger individuals when observing mothers and experienced individuals17,27,28,29.

Until the necessary research is done to elucidate the learning mechanisms of chimpanzee tool use in the wild we interpret our results in terms of a ‘cultural bias’, which constrains how chimpanzees of different communities perceive and evaluate their environment. Individuals acquire tool use in a socially-structured environment but individual trial-and-error learning most likely plays a key role17,30, which is consistent with the idea of hybrid learning18. In some ways, it does not matter what sorts of social learning processes have been at work to build the community-specific habits that subjects rely on to solve the task31. Although habits can be acquired individually32, in chimpanzees this takes place in a social framework, giving each community its unique pattern and fulfilling therefore one of the main requirements of current definitions of animal culture33. The Sonso individuals simply did not see the affordances of the leafy stick as a dipping tool or a brush (and only a small number saw its functional properties as a sponge) probably because in this community tools are never used during food acquisition. Both Sonso and Kanyawara infants grow up in a world of leaves, twigs and branches and both spend significant amounts of time playing with these objects, especially as infants (Gruber, personal observations34). Nevertheless, as adults, Kanyawara individuals reliably develop habitual stick use during food acquisition20 while Sonso individuals do not, suggesting that experiences during early ontogeny play a key role. Since sticks are not used in Sonso for food acquisition, grooming, resting or travelling, the main diurnal activities of wild chimpanzees35, nor in sexual interactions, they may generally become considered as irrelevant objects, a phenomenon that can have powerful inhibitory effects on learning (cf the ‘learned irrelevance’ effect36).

The apparent cultural bias observed in these chimpanzees shows some interesting parallels to what has been termed ‘cultural override’ in humans37. In spatial cognition experiments, Haun et al. showed that children learn to adopt their own culture's coordinate system, although they initially all use the same spatial coordinate system. Similarly, some parts of the environment appear to become irrelevant to chimpanzees during development, possibly because their mothers and other experienced individuals do not show any interest in them. Future research needs to address how exposure to other individuals' actions during infancy may determine which aspects they will perceive as salient in adulthood. In sum, our results suggest that there is an important cognitive dimension to observed behavioural variants in wild chimpanzees26 and that adopting a more cognitive approach to the study of culture in chimpanzees may bring new insights in understanding similarities with and differences from human cultures.

Methods

Subjects and Study Sites

The Sonso community (01°43’N, 31°32’E) has been studied in the Budongo Forest since 1990 and has been fully habituated to human observers since 1994. At the time of the study, the community consisted of 69 individuals. The Kanyawara community (00°33’N, 30°21’E) has been continuously studied in Kibale National Park since 1987 and has been fully habituated since 1994. At the time of the study, the community consisted of 46 individuals. The distance between the two sites is about 180 km. Both Kanyawara and Sonso chimpanzees practice leaf-sponging on a customary basis, i.e. most members of the community show the behaviour1,2. Kanyawara chimpanzees can also be observed extracting fluids with sticks (‘fluid-dip’) on a habitual basis, i.e. the behaviour has been observed several times in several individuals. Fluid-dip has allegedly been absent in Sonso over 20 years of continuous observation22.

Set-up

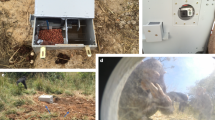

Natural honey was acquired from local bee keepers of the Masindi District, Uganda, whose bees of the genus Apis foraged freely in Budongo Forest. We manufactured portable logs from fallen trees in their respective natural habitats. All logs were standardised to a length of 50 cm and a width of 25 cm. We then drilled a rectangular-shaped hole of 4 by 5 cm (width × length) 16 cm deep in the middle of each log, using a manual drill (equal to the ‘obligatory’ condition in our previous study20). Logs were positioned in locations frequently visited by the chimpanzees, such as on a pathway or near a feeding tree. At Sonso, logs were placed under Ficus sur trees, which are frequently visited by this community22,38. In Kanyawara, the log was placed under a Ficus natalensis tree, which was fruiting at the time of the experiment. Twigs, climbers and leaves were available as potential raw material for tools in large quantities at both sites. Every morning, honey was poured into the hole by the experimenter (TG) to 10 cm below the surface. Additionally, honeycombs were used to cover the hole and protect it from insect invasion and to provide a conspicuous visual cue to the chimpanzees. A motion-sensitive video camera (PixController DVREye) was positioned to survey the hole and an immediate area of about 20 m2. All experiments were set up in the absence of chimpanzees. In Budongo, data were collected between February 20 and March 25, 2009 and September 14, 2009 and July 17, 2010. In Kibale, data were collected between April 2 and 22, 2009 and August 20 and 24, 2010.

Experimental conditions

Baseline condition (Sonso only)

Chimpanzees were allowed to engage freely with the apparatus, with no tool present. In our previous study20, Kanyawara chimpanzees had spent more time engaging with a similar apparatus and they produced a stick tool after an average engagement time of 20 s in the ‘obligatory’ condition, i.e. when access to honey was only possible with the use of a tool (N = 11 individuals). Some individuals tested at Sonso did not engage with the apparatus for 20 s and this opened the possibility that they simply did not have enough time to develop tool use. We addressed this by giving the Sonso individuals more time with the apparatus in the obligatory condition so that they matched the Kanyawara individuals in terms of mean engagement time. Because the main task in this experiment was identical to the obligatory condition in the previous 2009 experiment20, we established the baseline condition by combining the total engagement time for each individual. In both experiments, honey was enclosed in a small cavity that required inserting a tool to access it, although the dimensions of the substrate were very different (2009 study: large naturally fallen tree trunk; this study: 25 cm × 50 cm portable log). In the baseline condition we compared all individuals that had a combined engagement time with the apparatus of > 20 s when no tool was provided (table 1).

Experiment 1: Provisioning of the leafy stick

Chimpanzees at both sites were allowed to engage with the apparatus and a multi-functional tool, the ‘leafy stick’, which was positioned halfway between the hole and either edge of the log, randomly across trials. The tool was a 40 cm branch of Alstonia sp., a common shrub in Budongo and Kibale forests, stripped of all leaves on the lower 20 cm of its length. This way the leafy stick could be used either as a dipping device (by inserting the bare end), as a brush (by inserting the leafy end) or as a leaf-sponge (by removing and chewing its leaves and inserting the resulting sponge, figure 1). Skilled tool-users managed to access the honey in less than 10 minutes, by inserting the leafless end of the tool (‘stick’) or by removing the leaves and chewing them into a wadge (‘sponge’). The two techniques appeared similar in efficiency although we could not test this statistically because the honey provided was rarely consumed entirely in Sonso as leaf-spongers were often displaced by more dominant individuals. However, a comparison of the average duration spent by the most keen tool-users at Sonso (NT, sponge) and Kanyawara (QT, stick) during experiment 1 was 8.02 min (n = 2) and 8.21 min (n = 1).

With this experiment, our goal was to study if chimpanzees of different communities would find a particular part of the tool salient to use for the task, i.e. whether there were community-specific preferences, in line with the idea of a cultural bias in comprehending the environment. In contrast, if chimpanzees' selection of behaviour was only driven by environmental affordances, we would expect the chimpanzees to select the same behaviour to solve the task, independently of their community of origin.

Experiment 2: Highlighting the dipping function of the leafy stick (Sonso only)

In the second experiment, we only tested the Sonso individuals because most of them ignored the tool provided in experiment 1 and remained unsuccessful in getting honey. The leafy stick was directly inserted into the hole before the chimpanzees' arrival. This type of presentation was designed to make the alternative features of the tool particularly obvious because, when removing the tool from the hole, the honey would drip from the stick--sponging, i.e. experienced tool-users, we were interested in whether they would consider these alternative functions of the tool and favour any of them over of their existing leaf-sponging technique that they had transferred to this problem. For all other individuals, i.e. those who had never been observed manufacturing sponges or using other tools to extract resources, we were interested in whether this manipulation would make them learn stick use.

We tested five different settings to draw the attention of individuals to the dipping function of the tool: (a): stick part in cavity in contact with honey (dipping); (b): stick part in cavity in contact with honey, perforating through a comb (dipping); (c): leafy part in cavity in contact with honey (brushing); (d) stick part in cavity in contract with honey, but smaller 3×3 cm hole; (e): stick part in cavity in contact with honey, with stick features highlighted by an adult baboon who engaged with the log before chimpanzees and chewed on the stick. We considered the possible health implications of this condition and concluded that it was sufficiently natural given that baboons and chimpanzees often forage in the same trees and thus, are subject to each other's pathogens on a frequent basis (see appendix 1). Each of these different settings thus highlighted the dipping function of the leafy stick in different ways.

The main goal of experiment 2 was to test whether the limited exposure to one of these settings could drive chimpanzees to develop stick use individually. It is not likely that Sonso chimpanzees ever encounter sticks left in natural bee-hives (because there are no other tool-using species in the forest that exploit honey). The experiment thus tested if affordance learning (and as such ‘ecological’ affordance), without any social influence, could trigger on its own the development of a certain cultural behaviour (‘fluip-dip’) in a naive chimpanzee community.

Ideally we would have tested all individuals in all settings. However, in field situations such experimental rigour is impossible to strive for, because experimenters have no control over individuals' travel decisions. As part of our commitment to keep the experimental manipulations inconspicuous, we never exposed a community for more than one week to a certain setting. We chose not conduct the complementary experiment at Kanyawara, i.e. providing a leaf-sponge next or in the hole, for health reasons. Leaf-sponges are produced by folding and chewing a bunch of leaves in the mouth, a manipulation that would have increased the risks of human pathogen transmissions.

Relevance of the comparative analysis and statistics

For the baseline condition, we compared the results of these experiments with results obtained in our previous study20. We used a 20 s criterion in the baseline condition as described above. This was done to control for overall subject participation and exposure to this task and as a measure of motivation. We compared the total duration of engagement with the hole in both communities, especially before a tool was manufactured. In experiment 1 and 2, however, given that chimpanzees in the two communities differed in their choices of behaviour towards the leafy stick in community-specific ways, we favoured a behavioural comparison and did not use any temporal criterion. All statistical tests were calculated with PASW Statistics v. 18.0.

References

Whiten, A. et al. Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature 399, 682–685 (1999).

Whiten, A. et al. Charting cultural variation in chimpanzees. Behaviour 138, 1481–1516 (2001).

Whiten, A. & van Schaik, C. P. The evolution of animal ‘cultures’ and social intelligence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 362 (2007).

McGrew, W. C. in The question of animal culture (eds Laland K. N., & Galef B. G.) 41–69 (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Boesch, C. Is culture a golden barrier between human and chimpanzee? Evolutionary Anthropology 12, 82–91 (2003).

Galef, B. G. in The question of animal culture (eds Laland K. N., & Galef B. G.) 222 – 246 (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Tomasello, M. in The question of animal culture (eds Laland K. N., & Galef B. G.) 198–221 (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364, 2045–2415 (2009).

Call, J. & Tennie, C. Aninmal culture: Chimpanzee table manners? Current Biology 19, R981–R983 (2009).

Tomasello, M. in “Language” and intelligence in monkeys and apes: Comparative developmental perspectives (eds Parker S., & Gibson K.) 274–311 (Cambridge University Press, 1990).

Tomasello, M. in Social learning in animals: The roots of culture (eds Galef B., & Heyes C.) 319–346 (Academic Press, 1996).

Tomasello, M., Davis-Dasilva, M., Camak, L. & Bard, K. Observational learning of tool-use by young chimpanzees. Human Evolution 2, 175–183 (1987).

Hopper, L. M., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J. & Whiten, A. Observational learning in chimpanzees and children studied through ‘ghost’ conditions. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 275, 835–840 (2008).

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. Evidence for emulation in chimpanzees in social settings using the floating peanut task. Plos ONE 5, e10544 (2010).

Hopper, L. M. et al. Experimental studies of traditions and underlying transmission processes in chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour 73, 1021–1032 (2007).

Laland, K. N. & Galef, B. G. (eds) The question of animal culture (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Matsuzawa, T. et al. in Primate origin of human behavior and cognition (ed Matsuzawa T.) 557–574 (Springer, 2001).

Sterelny, K. The evolution and evolvability of culture. Mind & Language 21, 137–165 (2006).

Byrne, R. W. Commentary on Boesch, C. and Tomasello, M. Chimpanzee and human culture. Current Anthropology 39, 604–605 (1998).

Gruber, T., Muller, M. N., Strimling, P., Wrangham, R. W. & Zuberbühler, K. Wild chimpanzees rely on cultural knowledge to solve an experimental honey acquisition task. Current Biology 19, 1806–1810 (2009).

Gruber, T. et al. The influence of ecology on chimpanzee cultural behaviour: A case study of 5 Ugandan chimpanzee communities. (submitted).

Reynolds, V. The chimpanzees of the Budongo forest: Ecology, behaviour and conservation. (Oxford University Press, 2005).

Marshall-Pescini, S. & Whiten, A. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and the question of cumulative culture: An experimental approach. Animal Cognition 11, 449–456 (2008).

Hrubesch, C., Preuschoft, S. & van Schaik, C. P. Skill mastery inhibits adoption of observed alternative solutions among chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Animal Cognition 12, 209–216 (2009).

Yamamoto, S., Yamakoshi, G., Humle, T. & Matsuzawa, T. Invention and modification of a new tool use behavior: Ant-fishing in trees by a wild chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) at Bossou, Guinea. American Journal of Primatology 70, 699–702 (2008).

Matsuzawa, T., Tomonaga, M. & Tanaka, M. (eds) Cognitive development in chimpanzees (2006).

Lonsdorf, E. V., Everly, L. E. & Pusey, A. E. Sex differences in learning in chimpanzees. Nature 428, 715–716 (2004).

Lonsdorf, E. V. Sex differences in the development of termite-fishing skills in the wild chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, of Gombe National Park, Tanzania. Animal Behaviour 70, 673–683 (2005).

Biro, D. et al. Cultural innovation and transmission of tool use in wild chimpanzees: Evidence from field experiments. Animal Cognition 6, 213–223. (2003).

Fragaszy, D. M. & Visalberghi, E. Socially biased learning in monkeys. Learning & Behavior 32, 24–35 (2004).

de Waal, F. B. M. & Bonnie, K. E. in The question of animal culture (eds Laland K. N., & Galef B. G.) 19–39 (Harvard University Press, 2009).

Pesendorfer, M. B. et al. The maintenance of traditions in marmosets: individual habit, not social conformity? A field experiment. Plos ONE 4, e4472 (2009).

Quiatt, D. & Reynolds, V. Primate behaviour: Information, social knowledge and the evolution of culture. (Cambridge University Press, 1993).

Kahlenberg, S. M. & Wrangham, R. W. Sex differences in chimpanzees' use of sticks as play objects resemble those of children. Current Biology 20, R1067–R1068 (2010).

Goodall, J. The chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of behavior. (Harvard University Press, 1986).

Mackintosh, N. J. The psychology of animal learning. (Academic Press, 1974).

Haun, D. B. M., Rapold, C. J., Call, J., Janzen, G. & Levinson, S. C. Cognitive cladistics and cultural override in Hominid spatial cognition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 17568–17573 (2006).

Newton-Fisher, N. E. The diet of chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology 37, 344–354 (1999).

Acknowledgements

Permission to conduct research was given by Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), Ugandan National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) and National Forestry Authority (NFA). Ethical approval was given by the School of Psychology, University of St Andrews. We are grateful to the Royal Zoological Society of Scotland for providing core funding for the Budongo Conservation Field Station. Research at Kibale was supported by a grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation (award 0416125). We are especially grateful to Stephen Amati, James Kyomuhendo and Emily Otali for help with fieldwork. The study was supported by the Leverhulme Trust (UK). We commemorate the Congolese workers in the oil palm plantation owned by Lord Leverhulme.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.G and K.Z: designed research; T.G performed research and analysed data; T.G and K.Z. wrote the paper; M.N.M., R.W. and V.R. contributed technical expertise. All co-authors reviewed the paper.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Video 1

Supplementary Information

Video 2

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Gruber, T., Muller, M., Reynolds, V. et al. Community-specific evaluation of tool affordances in wild chimpanzees. Sci Rep 1, 128 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00128

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00128

This article is cited by

-

Functional fixedness in chimpanzees

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Hierarchical object combination and tool use in the great apes and human children

Primates (2022)

-

Well-digging in a community of forest-living wild East African chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii)

Primates (2022)

-

Dead-infant carrying by chimpanzee mothers in the Budongo Forest

Primates (2022)

-

Maintenance of prior behaviour can enhance cultural selection

Scientific Reports (2021)

Claudio Tennie

Our comment on Gruber et al. (2011)

In the continuing quest to understand the role of social learning in observed chimpanzee ?cultures?, the work of Gruber et al. (2011) represents an exciting attempt at untangling this hotly-contested issue experimentally. Gruber and colleagues describe data that builds on a previous published study by the same lead authors (Gruber et al. 2009). Importantly, in addition to a replication of their earlier study?s findings (Experiment 1 in Gruber et al. 2011) they also attempted to illicit a honey-dipping technique in a population that did not show this behavior before through the provisioning of an artificial honeycomb and ?highlighted? dipping tools (Experiment 2). Crucially, the tools provided were sticks with leaves attached; a double-ended tool. Chimpanzees in another population (Kanyawara, studied previously by Gruber et al., 2009) are proficient honey-dippers while this second group of chimpanzees (Sonso) have not been observed to honey-dip – however they are known to use leaves for leaf-sponging. In this current study (Experiment 2) the authors were interested to see whether the chimpanzees at Sonso were predicated to use the leaves provided (which, according to the authors, would be a sign of ?cultural bias?) or whether they were able to spontaneously use the stick provided and learn the new dipping behavior, as observed by chimpanzees at Kanyawara (Gruber et al., 2009; which Whiten et al., 1999 also reported as a ?customary? habit). We applaud the efforts of this ambitious and noteworthy study (and of field experiments like these in general, see also e.g. Thornton & Malapert, 2009 van de Waal et al., 2009), however we have a number of misgivings both about the methods used and the underlying theory proposed and we wish to take this opportunity to present our views in turn.

Firstly, the authors claim that there was no difference in levels of motivation between the two communities with regards to their interest in honey-dipping and therefore the likelihood to use the task. Yet, as there was never a shortage of tool material for either one of the techniques (sticks for dipping or leaves for sponging) we question why the Sonso chimpanzees should switch techniques, when they have one that already works? If, for example, someone is used to using a hammer to drive a nail into wood, why should she switch to using a stone – especially if she is surrounded by hammers? Likewise, there was never a shortage of leaf material for the Sonso chimpanzees, as tests took place in the field. Furthermore, sticking with our example, the person will simply know that the hammer will work, but – lacking the relevant experience – choosing the stone would be a gamble for her, a gamble that seems especially unnecessary given the abundance of hammers around her. This reasoning would even remain true if – in our example – the hammer and stone were, in fact, equally efficient (i.e. the hammer would still remain the ?safe? option). Of course, if one tool (here, the hammer) is more efficient than the other (here, the stone), then the bias towards one behavioral method over the other influences responses even more greatly.

Considering the chimpanzees? techniques studied by Gruber et al., what if the Sonso community?s leaf sponging technique is more efficient than the stick method used by the chimpanzees at Kanyawara? Crucially, the authors provide no information about the respective efficiency of the two methods – something that undermines their theoretical claims. ?Playing it safe? is just one of many strategies that could explain the lack of exploration by Sonso chimpanzees, others include ?conservatism? (Hrubesch et al., 2009) and ?functional fixedness? (Hanus et al., 2011) which we discuss in more detail below. For this reason, we propose that it would be worth running the reverse study: namely providing the Kanyawara chimpanzees with the affordances of the Sonso technique or alternatively, if the stick is indeed a more efficient strategy for dipping (or if this would be hard to do), to provide both groups with a task for which leaf sponging (or another such Sonso-specific behavior) is the more efficient method. Motivation should be enhanced by the prospect of a more efficient method (though of course it is always hard to know a priori if a new method would be better, which renders every switch of methods a gamble with an unsure outcome). But the general point of motivation reaches deeper: the very fact that few Sonso subjects did even use their respective hammer equivalent (i.e., the leaf technique; see Gruber et al. 2011) speaks (to us) of the fact that the Sonso subjects studied by Gruber et al. were indeed generally unmotivated. And while we agree that there was a potential confound with success levels, the fact remains that there was a trend that Sonso chimpanzees were generally less engaged with the task compared to Kanyawara chimpanzees (13/20 (65%) Kanyawara chimpanzees used the stick method compared to 7/42 (17%) chimpanzees at Sonso which used their leaf method). In sum, we believe the methodological logic of the experiment was flawed, which renders the data more or less uninterpretable.

In addition to our concerns with the methods used by Gruber et al., we take issue with the distorted interpretation of Tennie et al.?s (2009) paper and we wish to take this opportunity to clarify certain topics. For example, Gruber et al. failed to mention Tennie et al.?s interpretation of community specific ways to use different tool types (for basically the same activity). Tennie et al. did indeed explain such differences within their own account of chimpanzee culture (the ?Zone of Latent Solutions? hypothesis) and described them as ?cultural founder effects?. The neglect by Gruber et al. to acknowledge this theory is all the more surprising since the earlier ? sister paper of Gruber and colleagues (2009) was explicitly criticized for this same issue by Call & Tennie (2010 cited by Gruber et al. 2011). Thus, Call & Tennie wrote: ?Furthermore, in the past, group A invented the use of leaves while group B invented the use of sticks?and both behaviour patterns then stayed via such mechanisms [i.e., mechanisms subsumed within the ZLS account] with their groups. As a consequence, group A will be more likely to explore their world with leaves, while group B will be more likely to use sticks (this we have called the ?founder effect?).? This critique still stands, even given the results of the current Experiment 2, as these are also fully in line with the proposed founder effect. Besides this founder effect, the previously described chimpanzee conservatism (Hopper et al., 2011 Hrubesch et al. 2009, Marshall-Pescini & Whiten, 2008) and functional fixedness (Price et al., 2009 Hanus et al. 2011) are likewise able to explain the patterns found.

In addition, Gruber et al. (2011) write that Tennie et al. (2009) claimed that chimpanzees? latent solutions are a) purely affordance learning and b) must happen quickly and c) must happen always for every subject. This is not correct. Tennie et al.?s (2009) ZLS hypothesis clearly states that social factors do play a role in chimpanzee culture, something supported by our own research showing the importance of social information for chimpanzee social learning (e.g. Hopper et al., 2007, 2008.Tennie et al. 2010; all cited by Gruber et al.) But more importantly, nowhere in the accounts of Tennie et al. do they claim that target behavior should spontaneously appear in all chimpanzee subjects when first tested for a new behavior. Note also that in Gruber et al., 2011 – Experiment 2 – only 20 of the 69 chimpanzees in the Sonso community were recorded to interact with the log and tools – but information about the duration of this second experiment is not provided so perhaps with more time more of the Sonso community would have interacted (successfully) with the stick.

In fact Tennie et al.?s hypothesis makes a totally different claim. The ZLS hypothesis states that behavior that is potentially inventable by a single chimpanzee (i.e. unaided by demonstration of any kind) will be more likely to appear when given such demonstrations (especially in a social setting, see Tennie et al. 2010). Thus, The ZLS hypothesis is a hypothesis firmly based in probabilistic thinking, contrary to the claims of Gruber et al. (2011). Add to this the founder effects (see above), and Gruber et al.?s data gathered in their Experiment 2 does equally support Tennie et al.?s views. It might however be argued that Tennie et al.?s interpretation is more parsimonious, as it does require less assumptions.

Further to our global concerns of theory we also wish to highlight the paucity of key methodological detail provided by Gruber et al. (2011). We realize that ?Scientific Reports? require a short-format but none-the-less there are key details omitted which would be required for a thorough interpretation of these data and could easily have been placed in Table 1. Namely, demographic information is lacking. Chimpanzee ages are provided but only in age-class categories and the sex of the chimpanzees are never reported. Secondly, the length of each exposure and the season would be useful information as corresponding food availability for each community and for each experiment may have impacted the animals? motivation. Although the overall testing dates are given, when each test was run is not stated, or comment given on the availability of other food sources at the time, and whether they differed between communities (or even if honey was an equally-desirable food for both communities ? which feeds back into our discussion of motivational factors).

Ultimately, we appreciate the complexities associated with running experiments in the field, and as stated above we commend the report by Gruber et al. as it gives greater depth to our current understanding of wild chimpanzee cultures, we just wished through this commentary, to highlight what we believe to be, a more parsimonious interpretation of their data.

Written by:

Claudio Tennie (MPI EVA, Leipzig, Germany)

&

Lydia Hopper (CEBUS lab, Georgia State University, USA)

References:

Call, J. & Tennie, C. (2009) Animal culture: chimpanzee table manners? Current Biology 19(21): R981-R983.

Gruber, T., Muller, M N., Reynolds, V., Wrangham, R. & Zuberbühler, K. (2011) Community-specific evaluation of tool affordances in wild chimpanzees. Scientific Reports 1(128)

Gruber, T., Muller, M. N., Strimling, P., Wrangham, R. & Zuberbühler, K. (2009) Wild chimpanzees rely on cultural knowledge to solve an experimental honey acquisition task. Current Biology 19(21): 1806-1810.

Hanus, D., Mendes, N., Tennie, C. & Call., J. (2011). Comparing the performances of apes (Gorilla gorilla, Pan troglodytes, Pongo pygmaeus) and human children (Homo sapiens) in the floating peanut task. PLoS ONE. 6, e19555.

Hopper, L. M., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J. & Whiten, A. (2008) Observational learning in chimpanzees and children studied through ?ghost? conditions. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 275(1636): 835-840.

Hopper, L. M., Schapiro, S. J., Lambeth, S. P. & Brosnan, S. F. (2011) Chimpanzees' socially maintained food preferences indicate both conservatism and conformity. Animal Behaviour. 81(6): 1195-1202.

Hopper, L. M., Spiteri, A., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J., Horner, V. & Whiten, A. (2007) Experimental studies of traditions and underlying transmission processes in chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour 73(6): 1021-1032.

Hrubesch, C., Preuschoft, S. & van Schaik, C. P. (2009) Skill mastery inhibits adoption of observed alternative solutions among chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Animal Cognition 12(2): 209-216.

Marshall-Pescini, S. & Whiten, A. (2008) Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and the question of cumulative culture: an experimental approach. Animal Cognition 11(3): 449-456.

Price, E. E., Lambeth, S. P., Schapiro, S. J. & Whiten, A. (2009) A potent effect of observational learning on chimpanzee tool construction. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 276(1671): 3377-3383.

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. (2009) Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 364(1528): 2405-2415.

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. (2010) Evidence for emulation in chimpanzees in social settings using the floating peanut task. PLoS ONE 5(5): e10544.

Thornton, A. & Malapert, A. (2009). The rise and fall of an arbitrary tradition: an experiment with wild meerkats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 276: 1269-1276.

van de Waal, E., Renevey, N., Favre, C. M., & Bshary, R. (2010). Selective attention to philopatric models cause directed social learning in wild vervet monkeys. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 277: 2105-2111

Whiten, A., Goodall, J., McGrew, W. C., Nishida, T., Reynolds, V., Sugiyama, Y., Tutin, C. E. G., Wrangham, R. W. & Boesch, C. (1999). Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature, 399: 682-685.

Thibaud Gruber

We thank Tennie and Hopper (subsequently referred to as T&H) for their comments on our study. T&H have raised a number of methodological and theoretical concerns that we wish to address.

T&H first ask why we would expect Sonso chimpanzees to start using sticks considering that they already have an established and efficient leaf sponging technique available. In response to this, we wish to point out that we sampled a large number of individuals (N=29) in the key experimental condition (honey trapped in a 16 cm deep cavity, inaccessible without a tool) to find that only 7 (24.1%) produced a leaf sponge to access the honey (Results, p2, Baseline, 1st paragraph). The remaining 22 individuals, although motivated to engage with the apparatus, were unable to access the honey. We took this as a clear demonstration that leaf-sponging was not generally available to this community as a solution to our experimental problem. This finding provided the rationale for our second experiment in which we artificially highlighted one potential behaviour and solution, fluid-dip (as defined in Whiten et al. 2001).

Our data do not suggest that stick use was more efficient that leaf-sponging. The two most highly motivated tool users at Kanyawara (QT) and Sonso (NT) both managed to retrieve the honey in about 8 minutes with their respective techniques (Methods, p6, Right column, 1st paragraph). Unfortunately, it was not possible to conduct a systematic analysis across individuals because most were displaced by more dominant individuals and thus never managed to complete the task. However, results from QT and NT, who were able to work without being disturbed, provide a reasonable estimate of how quickly the task could have been solved.

T&H proposed a further experimental condition in order to explore how the Kanyawara community would behave in a matched situation, i.e. using leaf-sponges to access the honey. We agree that this would be the logically proper experiment to do. However, leaf-sponge production is a relatively complex task by which chimpanzees fold, crush and manoeuvre leaves in their mouths before using them as a wedged sponge to absorb liquid. Although it would have been possible for a human experimenter to replicate this process, we were concerned about the possibility of disease transmission and thus decided against this manipulation.

It is also relevant that most Kanyawara chimpanzees spontaneously produced a stick-solution in the 16 cm deep experimental condition. Our prediction for the Kanyawara community was that individuals would not have switched techniques anyway, a reflection of their well documented conservatism in similar contexts (Hrubesch et al. 2009, Marshall-Pescini & Whiten 2008). In sum, experiment 2, the focus of the current study, was only suitable for members of the Sonso community because the majority of these individuals did not have any preconceived notions of how to solve our experimental problem.

It is important to highlight that experiments were conducted in the same way in both communities. Specifically, we placed portable logs in the vicinity of favourite food trees (Kanyawara: Ficus natalensis, see Potts et al. in press Sonso: Ficus sur see Newton-Fisher, 1999, Gruber et al., submitted), suggesting that motivational differences are a poor explanation of the observed behavioural differences.

T&H also made a number of theoretical points and suggest some alternative interpretations. In particular, they invoke the notion of conservatism to explain the observed behavioural differences. We do not think that this interpretation is very powerful, notably because the main reason that chimpanzees failed to solve the problem was not because they chose the wrong technique, but because they were unable to understand that tool use was the only possible solution to the problem. It appears to us that the notion of chimpanzee conservatism can only be invoked when individuals already have a well established technique that helps them to achieve a desired outcome, not when they do not have any. As discussed before, a large majority of Sonso individuals were unable recruit tools to solve this problem.

A further point advanced by T&H is that our results support their ?Zone of Latent Solutions? hypothesis (ZLS hypothesis: Tennie et al. 2009). The main idea here is to investigate ??whether a certain behaviour falls under the zone of latent solutions i.e. if it is capable of being invented by naïve individuals and thus is not a candidate for cumulative culture? (Tennie & Hedwig 2009, p.101). In other words, if naïve individuals were to be given the necessary material to complete a certain task and managed to complete the task the same way as experienced individuals, then there would be no need to invoke complex cultural scenarios to explain the development of the behaviour.

The ZLS hypothesis has some implications for prior arguments about cultural behaviours in chimpanzees (e.g. Whiten et al 1999) and results of our experiment 2 are relevant in this context. If ?fluid-dip? is part of the Sonso chimpanzees unrealised behavioural repertoire, then the ZLS hypothesis predicts that some individuals will develop the behaviour, provided they have prior experience with the relevant materials (leaves, twigs and branches), genetic potential (Eastern chimpanzees routinely develop stick use in captivity) and the relevant physical causal understanding (Sonso chimpanzees use leaf-sponges to extract water).

We agree with T&H that the fluid-dip behaviour could eventually emerge in the Sonso community, for example if its members were repeatedly exposed to a stick inserted into the honey-filled cavity. However, we were less interested in how heavy human interference could impact on chimpanzee behaviour but how novel behaviour could appear under natural conditions. In relation to the ZLS hypothesis, the important finding in our study was that not one single naïve individual developed the fluid-dip behaviour, despite the fact that 20 individuals engaged with the task.

We do not wish to argue that fluid-dip should be considered a cultural behaviour, simply because no Sonso individual developed it during our experiments. To the contrary, we are of the opinion that our experiments reveal something about the impact of prior knowledge (which may well impact on the ZLS) and relatively little about the distinction between cultural and non-cultural behaviours. If the notion of a ZLS turns out to be a useful one, then surely an individual?s ZLS will be influenced by experiences during ontogeny. For instance, watching others using sticks to extract food may influence its personal ZLS, and alter it compared to others who have never witnessed stick use. In summary, an individual?s Zone of Latent Solutions may be strongly affected by its ontogenic experiences, and this obviously varies from one community to the next, suggesting that ZLSs are partly culturally determined.

Written by:

Thibaud Gruber (University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK),

Vernon Reynolds (University of Oxford, UK),

&

Klaus Zuberbühler (University of St Andrews, Scotland, UK)

References:

Gruber, T., Muller, M N., Reynolds, V., Wrangham, R. & Zuberbühler, K. (2011) Community-specific evaluation of tool affordances in wild chimpanzees. Scientific Reports 1(128)

Gruber, T., Muller, M. N., Strimling, P., Wrangham, R. & Zuberbühler, K. (2009) Wild chimpanzees rely on cultural knowledge to solve an experimental honey acquisition task. Current Biology 19(21): 1806-1810.

Gruber, T., Krupenye, C., Byrne, M.-R., Mackworth-Young, C. McGrew, W.C., Reynolds, V. & Zuberbühler, K. (submitted). The influence of ecology on animal cultural behaviour: A case study of three Ugandan chimpanzee communities.

Hrubesch, C., Preuschoft, S. & van Schaik, C. P. (2009) Skill mastery inhibits adoption of observed alternative solutions among chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). Animal Cognition 12(2): 209-216.

Marshall-Pescini, S. & Whiten, A. (2008) Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and the question of cumulative culture: an experimental approach. Animal Cognition 11(3): 449-456.

Newton-Fisher, N. E. (1999). The diet of chimpanzees in the Budongo Forest Reserve, Uganda. African Journal of Ecology, 37(3), 344-354.

Potts, K. B., Watts, D. P., & Wrangham, R. W. (in press). Comparative feeding ecology of two chimpanzee communities in Kibale National Park, Uganda. International Journal of Primatology.

Tennie, C., Call, J. & Tomasello, M. (2009) Ratcheting up the ratchet: on the evolution of cumulative culture. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences 364(1528): 2405-2415.

Tennie, C. & Hedwig, D. (2009) How latent solution experiments can help to study differences between human culture and primate traditions. In Primatology: Theories, Methods and Research (Ed. E. Potocki & J. Krasinski), pp. 95-112. Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Whiten, A., Goodall, J., McGrew, W. C., Nishida, T., Reynolds, V., Sugiyama, Y., Tutin, C. E. G., Wrangham, R. W. & Boesch, C. (1999). Cultures in chimpanzees. Nature, 399: 682-685.

Whiten, A., Goodall, J., McGrew, W. C., Nishida, T., Reynolds, V., Sugiyama, Y., Tutin, C. E. G., Wrangham, R. W. & Boesch, C. (2001). Charting cultural variation in chimpanzees. Behaviour, 138: 1481-1516.

Elysia Altuntas

This is a teet