Abstract

Anodic oxide fabricated by anodizing has been widely used for nanostructural engineering, but the nanomorphology is limited to only two oxides: anodic barrier and porous oxides. Therefore, the discovery of an additional anodic oxide with a unique nanofeature would expand the applicability of anodizing. Here we demonstrate the fabrication of a third-generation anodic oxide, specifically, anodic alumina nanofibers, by anodizing in a new electrolyte, pyrophosphoric acid. Ultra-high density single nanometer-scale anodic alumina nanofibers (1010 nanofibers/cm2) consisting of an amorphous, pure aluminum oxide were successfully fabricated via pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. The nanomorphologies of the anodic nanofibers can be controlled by the electrochemical conditions. Anodic tungsten oxide nanofibers can also be fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. The aluminum surface covered by the anodic alumina nanofibers exhibited ultra-fast superhydrophilic behavior, with a contact angle of less than 1°, within 1 second. Such ultra-narrow nanofibers can be used for various nanoapplications including catalysts, wettability control and electronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anodizing aluminum has been widely investigated in various research and industrial fields, including nanostructure fabrication, electronic devices and corrosion protection. Over the past 100 years, the anodic oxide formed by anodizing has typically been classified into two different groups: a) anodic barrier oxide and b) anodic porous oxide1,2,3,4,5,6. Anodizing aluminum in neutral solutions, such as borate, adipate and citrate electrolytes, causes the formation of an anodic barrier oxide, which consists of dense, compact amorphous alumina with a maximum thickness of 1 μm7,8,9. Anodic barrier oxide possesses a high dielectric property and is widely used for electrolytic capacitor applications. In contrast, anodic porous oxide is formed by anodizing in acidic solutions, including sulfuric, selenic, phosphoric, chromic, carboxylic and oxocarbonic acids10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, because the anodic oxide is locally dissolved in acidic solutions. Porous oxide consists of ordered hexagonal cells with a maximum thickness of several 100 μm, where each cell exhibits vertical nanopores at its center. Porous oxide is widely used as a corrosion-resistant coating in the fields of building and aerospace. In addition, porous oxide has also been used as a nanotemplate for various nanoscale applications in the pioneering works of Masuda et al., who reported on a self-ordering porous oxide and a two-step anodizing technique23,24,25. Highly ordered porous oxide has been studied for potential use in various ordered-nanostructure applications26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Several research groups have reported on the growth behavior of anodic porous oxide via anodizing in viscous organic solvent-water mixture solution35,36,37,38. In these anodizing processes, ethylene glycol or glycerol was typically used as a viscous solvent and large-scale anodic porous oxide could be successfully obtained. Very recently, porous oxide technology includes various other valve metals such as titanium and hafnium, as reported by Schmuki et al39,40,41. Meanwhile, because the nanomorphology is limited to these two types of anodic oxide, the discovery of an additional anodic oxide with different and unique nanofeatures would expand the applicability of anodizing.

In the present investigation, we report a novel anodic oxide, ultra-high density single-nanometer-scale alumina nanofibers, fabricated via anodizing in a new electrolyte, pyrophosphoric acid (H4P2O7). This interesting inorganic electrolyte is formed by the dehydration of phosphoric acid and shows highly viscous behavior at room temperature. Note that pyrophosphoric acid acts as a viscous electrolyte during anodizing. We found that pyrophosphoric acid anodizing creates ultra-high density alumina nanofibers with single nanometer-scale diameters. Anodic nanofibers grow over time during anodizing and high-aspect-ratio pure alumina nanofibers can be successfully obtained on an aluminum specimen. Surface structural control of the anodic alumina nanofibers can be achieved via an electrochemical approach during anodizing. These anodic nanofibers provide superhydrophilic properties (less than a 1° water contact angle) to the surface within only 1 second. Moreover, this novel anodic nanofiber fabrication can be applied to other metals such as tungsten. The growth behavior of the anodic nanofibers is discussed in detail below.

Results

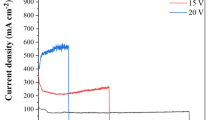

The changes in the anodizing voltage over time at several current densities in a concentrated pyrophosphoric acid solution at 293 K are shown in Fig. 1a. Anodizing was carried out using a simple two-electrode electrochemical cell without any special equipment (Supplementary Fig. 1). At i = 10 Am−2, the voltage linearly increased with the anodizing time and then remained at a constant value of 60 V. After reaching this plateau region, the voltage again increased with time and then exhibited an unstable oscillation. At large current densities, the slopes of the V-t lines in the initial period became much steeper with the current densities and similar oscillation behaviors were observed above 80 V. In these oscillation regions, the aluminum surface was covered by non-uniform white corrosion products formed by the active dissolution of aluminum (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, further constant voltage anodizing was carried out below 75 V for a uniform growth of anodic oxide.

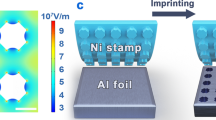

Anodizing in a pyrophosphoric acid solution at 293 K.

(a) Changes in anodizing voltage over time in a concentrated pyrophosphoric acid solution (293 K) at constant current densities of 5–40 Am−2 for 15 min. (b) and (c) Low- and high-magnification SEM images of the surface of a specimen anodized at 75 V for 24 h. Numerous alumina nanofibers grow on the aluminum specimen.

Figure 1b shows a scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of the anodic oxide obtained via constant voltage anodizing at 75 V for 24 h. The aluminum specimen was covered by numerous nanofibers of more than 1 μm in length and the nanofibers were tangled and bundled together. This novel nanofeatures, which looks like “anodic oxide hairs on aluminum”, is very different from that obtained by typical anodizing for barrier and porous anodic oxides5,6. High-magnification SEM observation (Fig. 1c) indicated that the anodic oxide consisted of three anodic layers: a thin barrier oxide, a honeycomb oxide and nanofibers. The nanomorphology of the barrier and honeycomb oxides is somewhat similar to the porous alumina formed by typical acid anodizing: nanopores in the porous alumina are separated from the aluminum substrate by the thin barrier oxide. In our case, however, the honeycomb oxide consisted only of very narrow hexagonal walls and it is more of a porous oxide than a network oxide. In addition, note that nanofibers grow at the triple (or quadruple) points of the narrow wall junctions in the honeycomb oxide (see yellow arrows). To analyze the growth behavior of these interesting nanofibers fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing, the details of the surface nanofeatures under various electrochemical conditions were examined by SEM and transmission electron microscopy (TEM).

Figure 2a shows SEM images of an aluminum specimen anodized in a pyrophosphoric acid solution for 10 min. It is clear that an anodic oxide with a thin barrier layer and a honeycomb structure had formed within the 10 min of anodizing. In addition, numerous nanofibers approximately 10 nm in diameter are observed at the apices of the honeycomb structure, which fell down onto the surface due to their own weight. The density of the nanofibers was measured to be 1.8 × 1010 nanofibers/cm2 by SEM observations. As the anodizing time was increased to 30 min (Fig. 2b), the nanofibers developed longer lengths and narrower shapes and large areas of the surface were covered by these grown nanofibers. Interestingly, there was no change in the nanomorphology of the barrier or honeycomb oxides as the anodizing time increased. These SEM observations indicate that only the nanofibers grow with time during pyrophosphoric acid anodizing while the barrier and honeycomb layers are not changed.

Ultra-high density single nanometer-scale anodic alumina nanofibers.

(a), (b) and (c) SEM images of an aluminum specimen anodized in pyrophosphoric acid solution (293 K) at a constant voltage of 75 V for 10 min, 30 min and 120 min. The bottom rows of (a) and (b) show high-magnification SEM images and (c) shows a high-resolution TEM image and its diffraction pattern. High-aspect-ratio, single nanometer-scale anodic alumina nanofibers consisting of an amorphous oxide are formed on the specimen. (d) EELS spectra of nanofibers and barrier/honeycomb oxide layers. The nanofibers consist of amorphous, pure aluminum oxide. In contrast, the barrier and honeycomb oxides contain pyrophosphoric anion incorporated by the electric field during anodizing.

After 24 h of anodizing, micrometer-scale-length nanofibers covered the honeycomb structure (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 3). A TEM image and its diffraction pattern show amorphous, narrow nanofibers 6.9–9.1 nm in diameter. As determined by electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS, Fig. 2d), the nanofibers consisted of amorphous, pure aluminum oxide without anions. However, the barrier and honeycomb oxides contain pyrophosphate anion of the electrolyte used. Such single nanometer-scale anodic alumina nanofibers can be classified as the third-generation anodic oxide, which is different from anodic barrier and porous oxides5,6. In addition, the nanomorphology of the anodic alumina nanofibers was significantly different under various electrochemical conditions. For example, the density of the alumina nanofibers increased with a decrease in the anodizing voltage because the diameter of the honeycomb structure decreased (Supplementary Fig. 4). The thickness of the barrier and honeycomb layers increased as the solution temperature decreased and anodic porous alumina without nanofibers was formed upon anodizing at 268 K (Supplementary Fig. 5). Therefore, temperatures below 273 K are not suitable for anodic nanofiber fabrication. Moreover, we found that anodic WO3 nanofibers can also be fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing of pure tungsten (Supplementary Fig. 6). This finding expands the applicability of oxide nanofiber fabrication to aluminum as well as various other metals39,40,41.

The fabrication technique described for novel anodic alumina nanofibers is useful for fabricating ultra-large quantities of single nanometer-scale oxide nanofibers. Moreover, we found that the aluminum surface covered with these anodic alumina nanofibers displays ultra-fast superhydrophilic behavior, with a contact angle of less than 1°, within 1 second. Figure 3 shows the water contact angle images of 2-μL droplets on a) electropolished aluminum, b) anodic porous alumina formed by sulfuric acid anodizing and c) anodic alumina nanofibers formed by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. The contact angle on the electropolished surface was 37.2° after dropping for 100 ms and there was no change in the contact angle after 1 s. The contact angle on the porous alumina was 14.3° for 100 ms and decreased to 8.4° at 1 s, but a water droplet still remained on the porous alumina. In contrast, a near-zero water contact angle was clearly observed on the nanofiber-covered surface within 1 s. Namely, the anodic alumina nanofibers formed by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing gave the surface a superhydrophilic property, with a contact angle of less than 1.0°. Such superhydrophilicity also appeared on a surface subjected to a long duration of anodizing. Well-known experimental results have demonstrated that titanium covered by titanium dioxide exhibits superhydrophilic behavior under ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, based on the photocatalytic activity42,43. However, note that our ultrafast superhydrophilicity based on anodic alumina nanofibers can be achieved regardless of the irradiation environment. Therefore, the surface covered by anodic alumina nanofibers demonstrates a superhydrophilicity as long as its nanomorphology with a clean surface is maintained.

Superhydrophilicity of the aluminum specimen covered with anodic alumina nanofibers.

CCD images of water droplets 100 ms and 1 s after dropping on (a) electropolished aluminum, (b) anodic porous alumina formed by sulfuric acid anodizing (293 K) at 20 V for 120 min and (c) anodic alumina nanofibers formed by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing (293 K) at 75 V for 10 min. The contact angle formed by the water droplet on the nanofiber-covered surface reaches less than 1° within 1 second, clearing indicating the superhydrophilic property of the specimen.

Discussion

Based on the experimental results, the growth behavior of anodic alumina nanofibers fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing is now discussed. Figure 4 shows a schematic model of the anodic alumina nanofiber growth. When a voltage is applied to the aluminum specimen, a thin compact barrier oxide is formed on the aluminum substrate at the very initial stage. With further anodizing, a honeycomb porous structure is then formed by a) the viscous flow of the oxide from the bottom of the honeycomb structure to the narrow oxide wall and b) local oxide dissolution, similar to that which occurs in anodic porous alumina fabrication (Fig. 4b)44,45,46. Namely, the barrier oxide transforms to porous oxide during anodizing. This transformation can typically be seen on the growth behavior of porous alumina formed in sulfuric, oxalic and phosphoric acid solutions. In these cases, the steady state growth of the anodic porous alumina can be observed during anodizing. However, it is clear that further growth behavior of our anodic alumina nanofibers is different from that obtained by typical anodizing reported previously. In our case, the anodic oxide formed at the triple points of the honeycomb structure consists of pure anodic alumina and its chemical stability in a concentrated pyrophosphoric acid solution (negative pH value) may be higher than that of the barrier and honeycomb oxides with the anions of the electrolyte used. Therefore, the insoluble pure alumina formed at the triple points can grow during anodizing, whereas the narrow oxide walls of the honeycomb structure can easily be chemically dissolved. Namely, the porous oxide also changes to nanofibers during anodizing (Fig. 4a and 4b). Such non-uniform anion distributions (with/without anions in the anodic oxide) are very important for the fabrication of anodic alumina nanofibers. However, the reason that the anions are non-uniformly distributed in the anodic oxide is still unknown; thus, further investigations are required. One possibility is that the high viscosity and high solubility of the pyrophosphoric acid electrolyte may affect the viscous flow of the anodic oxide during anodizing. Recently, the fabrication of alumina nanowires formed via anodizing/subsequent chemical etching in typical acidic electrolytes such as oxalic acid and the corresponding superhydrophobic property have been reported by several research groups; however, the electrochemical behavior and nanostructural features of alumina nanowires including the diameter and density have not been described in such studies47,48,49,50. The fabrication of these nanowires based on the chemical etching process and the surface appearance of our anodic alumina nanofibers is different from these alumina nanowires.

Growth model of anodic alumina nanofibers fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing.

(a) Schematic models of anodic barrier oxide, anodic honeycomb oxide and anodic nanofiber oxide. (b) SEM images of the surface of a specimen anodized via pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. The barrier oxide transforms to honeycomb oxide and then the honeycomb oxide also transforms to nanofibers during anodizing.

In summary, we have demonstrated a third-generation anodic oxide, anodic alumina nanofibers fabricated by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. Ultra-high density single nanometer-scale alumina nanofibers (1010 nanofibers/cm2) rapidly grow at the triple points of the honeycomb structure during anodizing and the structural features of the nanofibers can be controlled by electrochemical anodizing conditions such as voltage, time and temperature. Therefore, pyrophosphoric acid anodizing can be used as a novel fabricating technique for oxide nanofibers. An important advantage of our nanofiber fabrication process is that individual nanometer-sized anodic nanofibers can be fabricated over large areas of the electrode. Accordingly, the anodizing technique leads to ultra-fast superhydrophilic properties on the aluminum surface, with a contact angle of less than 1°. Moreover, pyrophosphoric acid anodizing can be applied to other metals, such as tungsten. Our novel anodizing method can be used for various nanoapplications such as catalysts, wettability control, filtration, energy storage, biomedical science, corrosion protection and electronic devices.

Methods

Pyrophosphoric acid anodizing

High-purity aluminum foils (99.99 wt%, Showa Denko and Nippon Light Metal, Japan) were ultrasonically degreased and electropolished in a 13.6 M CH3COOH/2.56 M HClO4 solution at 28 V for 1 min. The electropolished specimens were immersed in a concentrated pyrophosphoric acid solution (74.0–78.0%, Kanto Chemical, Japan, T = 268–313 K) and were anodized at a constant current density of i = 5–40 Am−2 and a constant cell voltage of V = 25–75 V for up to 24 h. The anodizing setup consisted of a two-electrode electrochemical cell with a platinum counter electrode and the electrolyte solution was slowly stirred with a magnetic stirrer during anodizing (rotation speed: 1 s−1). For anodic WO3 nanofibers, high-purity tungsten plates (99.95 wt%, Nilaco, Japan) were electropolished in a 2.5 M NaOH solution at 2.5 V for 40 s and then anodized in a pyrophosphoric acid solution at 293 K and 50 V for 120 min.

Material analysis

The nanomorphology of the anodized specimens was examined by SEM (JIB-4600F/HKD, JEOL) and TEM (JEM-2010F, JEOL). For SEM observations, a thin platinum or carbon electro-conductive layer was coated on the specimen by a sputter coater (Pt: MSP-1S, Vacuum Device, Japan, C: JEE-400, JEOL). For TEM observations, the anodized oxide, including the barrier, honeycomb and nanofiber oxides, was fixed on a copper TEM grid with a thin carbon film. Qualitative analysis of the incorporated anions in the anodic oxide was measured by EELS (JEM-2010F, JEOL). For the surface wettability, the water contact angle on a surface anodized by pyrophosphoric acid anodizing was measured by an optical contact angle meter (DM-CE1, Kyowa Interface Science, Japan) at room temperature. The average volume of the water droplet was adjusted to 2 μL.

References

Thompson, G. E., Furneaux, R. C., Wood, G. C., Richardson, J. A. & Gode, J. S. Nucleation and growth of porous anodic films on aluminium. Nature 272, 433–435 (1978).

Thompson, G. E. & Wood . Porous anodic film formation on aluminum. Nature 290, 230–232 (1981).

Furneaux, R. C., Rigby, W. C. & Davidson, A. P. The formation of controlled-porosity membranes from anodically oxidized aluminum. Nature 337, 147–149 (1989).

O'Sullivan, J. P. & Wood, G. C. Morphology and mechanism of formation of porous anodic films on aluminium. Proc. Roy. Cod. Lond. A 317, 511–543 (1970).

Thompson, G. E. Porous anodic alumina: fabrication, characterization and applications. Thin Solid Films 297, 192–201 (1997).

Lee, W. & Park, S. J. Porous Anodic Aluminum Oxide: Anodization and Templated Synthesis of Functional Nanostructures. Chem. Rev. 114, 7487–7556 (2014).

Shimizu, K. et al. Impurity distributions in barrier anodic films on aluminium: a GDOES depth profiling study. Electrochim. Acta 44, 2297–2306 (1999).

Li, Y. et al. Formation and breakdown of anodic oxide films on aluminum in boric acid/borate solutions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, 866–876 (1997).

Wood, G. C., Skeldon, P., Thompson, G. E. & Shimizu, K. A model for the incorporation of electrolyte species into anodic alumina. J. Electrochem. Soc. 143, 74–83 (1996).

Lee, W. et al. Structural engineering of nanoporous anodic aluminum oxide by pulse anodization of aluminum. Nat. Nanotechnol. 3, 234–239 (2008).

Lee, W., Ji, R., Gösele, U. & Nielsch, K. Fast fabrication of long-range ordered porous alumina membranes by hard anodization. Nat. Mater. 5, 741–747 (2006).

Masuda, H., Hasegwa, F. & Ono, S. Self-Ordering of Cell Arrangement of Anodic Porous Alumina Formed in Sulfuric Acid Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 144, L127–L130 (1997).

Asoh, H. et al. Fabrication of ideally ordered anodic porous alumina with 63 nm hole periodicity using sulfuric acid. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 19, 569–572 (2001).

Nishinaga, O., Kikuchi, T., Natsui, S. & Suzuki, R. O. Rapid fabrication of self-ordered porous alumina with 10-/sub-10-nm-scale nanostructures by selenic acid anodizing. Sci. Rep. 3, 2748 (2013).

Kikuchi, T., Nishinaga, O., Natsui, S. & Suzuki, R. O. Self-Ordering behavior of anodic porous alumina via selenic acid anodizing. Electrochim. Acta 137, 728–735 (2014).

Masuda, H., Yada, K. & Osaka, A. Self-ordering of cell configuration of anodic porous alumina with large-size pores in phosphoric acid solution. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37, L1340 (1998).

Li, A. P., Müller, F., Birner, A., Nielsch, K. & Gösele, U. Hexagonal pore arrays with a 50–420 nm interpore distance formed by self-organization in anodic alumina. J. Appl. Phys. 84, 6023–6026 (1998).

Stępniowski, W. J. et al. Fabrication of anodic aluminum oxide with incorporated chromate ions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 259, 324–330 (2012).

Kikuchi, T., Nakajima, D., Kawashima, J., Natsui, S. & Suzuki, R. O. Fabrication of anodic porous alumina via anodizing in cyclic oxocarbon acids. Appl. Surf. Sci. 313, 276–285 (2014).

Chu, S. Z., Wada, K., Inoue, S., Isogai, M. & Yasumori, A. Fabrication of Ideally Ordered Nanoporous Alumina Films and Integrated Alumina Nanotubule Arrays by High-Field Anodization. Adv. Mater. 17, 2115–2119 (2005).

Asoh, H., Nishio, K., Nakao, M., Tamamura, T. & Masuda, H. Conditions for fabrication of ideally ordered anodic porous alumina using pretextured Al. J. Electrochem. Soc. 148, B152–B156 (2001).

Sulka, G. D. & Stępniowski, W. J. Structural features of self-organized nanopore arrays formed by anodization of aluminum in oxalic acid at relatively high temperatures. Electrochim. Acta 54, 3683–3691 (2009).

Masuda, H. & Fukuda, K. Ordered metal nanohole arrays made by a two-step replication of honeycomb structures of anodic alumina. Science 268, 1466–1468 (1995).

Masuda, H. et al. Highly ordered nanochannel-array architecture in anodic alumina. Appl. Phys. Lett. 71, 2770–2772 (1997).

Masuda, H. & Satoh, M. Fabrication of gold nanodot array using anodic porous alumina as an evaporation mask. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 35, L126 (1996).

Nielsch, K., Müller, F., Li, A. P. & Gösele, U. Uniform nickel deposition into ordered alumina pores by pulsed electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 12, 582–586 (2000).

Sander, M. S., Prieto, A. L., Gronsky, R., Sands, T. & Stacy, A. M. Fabrication of High-Density, High Aspect Ratio, Large-Area Bismuth Telluride Nanowire Arrays by Electrodeposition into Porous Anodic Alumina Templates. Adv. Mater. 14, 665–667 (2002).

Asoh, H., Sasaki, K. & Ono, S. Electrochemical etching of silicon through anodic porous alumina. Electrochem. Commun. 7, 953–956 (2005).

Chu, S. Z., Inoue, S., Wada, K., Hishita, S. & Kurashima, K. Self-Organized Nanoporous Anodic Titania Films and Ordered Titania Nanodots/Nanorods on Glass. Adv. Funct. Mater. 15, 1343–1349 (2005).

Zhao, S., Chan, K., Yelon, A. & Veres, T. Novel structure of AAO film fabricated by constant current anodization. Adv. Mater. 19, 3004–3007 (2007).

Yamauchi, Y., Nagaura, T., Ishikawa, A., Chikyow, T. & Inoue, S. Evolution of standing mesochannels on porous anodic alumina substrates with designed conical holes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10165–10170 (2008).

Yanagishita, T., Nishio, K. & Masuda, H. Anti-reflection structures on lenses by nanoimprinting using ordered anodic porous alumina. Appl. Phys. Express 2, 022001 (2009).

Yamauchi, Y., Nagaura, T. & Inoue, S. Oriented growth of small mesochannels utilizing a porous anodic alumina substrate: preparation of continuous film with standing mesochannels. Chem.-Asian J. 4, 1059–1063 (2009).

Lin, Q., Hua, B., Leung, S. F., Duan, X. & Fan, Z. Efficient light absorption with integrated nanopillar/nanowell arrays for three-dimensional thin-film photovoltaic applications. ACS Nano 7, 2725–2732 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. Fabrication of ordered porous anodic alumina with ultra-large interpore distances using ultrahigh voltages. Mater. Res. Bull. 57, 116–120 (2014).

Leung, S. et al. Efficient photon capturing with ordered three-dimensional nanowell arrays. Nano Lett. 12, 3682–3689 (2012).

Wang, Q., Long, Y. & Sun, B. Fabrication of highly ordered porous anodic alumina membrane with ultra-large pore intervals in ethylene glycol-modified citric acid solution. J. Porous Mater. 20, 785–788 (2013).

Chen, W., Wu, J. & Xia, X. Porous anodic alumina with continuously manipulated pore/cell size. ACS Nano 5, 959–965 (2008).

Macak, J. M., Tsuchiya, H., Taveira, L., Aldabergerova, S. & Schmuki, P. Smooth anodic TiO2 nanotubes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 44, 7463–7465 (2005).

Tsuchiya, H. et al. Self-organized TiO2 nanotubes prepared in ammonium fluoride containing acetic acid electrolytes. Electrochem. Commun. 7, 576–580 (2005).

Wei, W. et al. Formation of Self-Organized Superlattice Nanotube Arrays–Embedding Heterojunctions into Nanotube Walls. Adv. Mater. 22, 4770–4774 (2010).

Song, Y. Y., Schmidt-Stein, F., Bauer, S. & Schmuki Amphiphilic TiO2 nanotube arrays: an actively controllable drug delivery system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4230–4232 (2009).

Miyauchi, M., Nakajima, A., Hashimoto, K. & Watanabe A highly hydrophilic thin film under 1 μW/cm2 UV illumination. Adv. Mater. 12, 1923–1927 (2000).

Houser, J. E. & Hebert, K. R. The role of viscous flow of oxide in the growth of self-ordered porous anodic alumina films. Nat. Mater. 8, 415–420 (2009).

Hebert, K. R., Albu, S. P., Paramasivam, I. & Schmuki, P. Morphological instability leading to formation of porous anodic oxide films. Nat. Mater. 11, 162–166 (2012).

Garcia-Vergara, S. J., Skeldon, P., Thompson, G. E. & Habazaki, H. A flow model of porous anodic film growth on aluminium. Electrochim. Acta 52, 681–687 (2006).

Kim, Y. et al. Robust Superhydrophilic/Hydrophobic Surface Based on Self-Aggregated Al2O3 Nanowires by Single-Step Anodization and Self-Assembly Method. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 5074–5078 (2012).

Peng, S., Tian, D., Yang, X. & Deng, W. Highly efficient and large-scale fabrication of superhydrophobic alumina surface with strong stability based on self-congregated alumina nanowires. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 4831–4841 (2014).

Peng, S., Tian, D., Miao, X., Yang, X. & Deng, W. Designing robust alumina nanowires-on-nanopores structures: Superhydrophobic surfaces with slippery or sticky water adhesion. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 409, 18–24 (2013).

Jeong, C. & Choi, C. H. Single-step direct fabrication of pillar-on-pore hybrid nanostructures in anodizing aluminum for superior superhydrophobic efficiency. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 842–848 (2012).

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted at Hokkaido University and was supported by the “Nanotechnology Platform” Program of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. The authors would like to thank Prof. Hiroki Habazaki, Mr. Takashi Endo and Mr. Katsutoshi Nakayama (Hokkaido University) for their assistance with the SEM observations and wettability measurements. This work was financially supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) “KAKENHI”, the Toyota Physical & Chemical Research Institute Scholars and the Nippon Sheet Glass Foundation for Materials Science and Engineering.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. and O.N. designed and performed the pyrophosphoric acid anodizing, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. D.N. and J.K. also performed the pyrophosphoric acid anodizing. S.N., N.S. and R.O.S. contributed to the analysis and the manuscript writing.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kikuchi, T., Nishinaga, O., Nakajima, D. et al. Ultra-High Density Single Nanometer-Scale Anodic Alumina Nanofibers Fabricated by Pyrophosphoric Acid Anodizing. Sci Rep 4, 7411 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07411

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep07411

This article is cited by

-

Formation of porous Ga oxide with high-aspect-ratio nanoholes by anodizing single Ga crystal

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Modelling experimental parameters for fabrication of nanofibres using Taguchi optimization by an electrospinning machine

Bulletin of Materials Science (2020)