Abstract

Controlling the angular momentum of spins with very short external perturbations is a key issue in modern magnetism. For example it allows manipulating the magnetization for recording purposes or for inducing high frequency spin torque oscillations. Towards that purpose it is essential to modify and control the angular momentum of the magnetization which precesses around the resultant effective magnetic field. That can be achieved with very short external magnetic field pulses or using intrinsically coupled magnetic structures, resulting in a transfer of spin torque. Here we show that using picosecond acoustic pulses is a versatile and efficient way of controlling the spin angular momentum in ferromagnets. Two or three acoustic pulses, generated by femtosecond laser pulses, allow suppressing or enhancing the magnetic precession at any arbitrary time by precisely controlling the delays and amplitudes of the optical pulses. A formal analogy with a two dimensional pendulum allows us explaining the complex trajectory of the magnetic vector perturbed by the acoustic pulses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since its discovery1, the ultrafast demagnetization and precession of the magnetization induced by femtosecond laser pulses has received intensive attention2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. How fast and how efficiently spins can be controlled are crucial matters in the field of ultrafast magnetism. In that regards, a coherent control of the magnetization requires to impulse a sudden change of the spins angular momentum which results in a motion of precession of the magnetic vector around the effective field. This is generally achieved via a change of the material anisotropy of the considered magnetic system using femtosecond laser pulses as demonstrated in various configurations of pump and probe pulses designed for manipulating the spins in magnetic semiconductors15,16,17,18, dielectrics19,20 or metals21. The laser source can advantageously be a terahertz pulse16, a photo- or an optomagnetic pulse20. Recently we reported that magneto-acoustic pulses can also be used for modifying the magnetization vector in ferromagnetic materials21. Alternatively one can induce a spin torque transfer between magnetically coupled layers, for example in multilayered material structures, a process that is usually achieved with currents but which can also be optically manipulated22,23. Inducing a motion of precession is important for generating spin torque oscillations and being able to control them allows for example to selectively picking up single frequency modes in superimposed temporal oscillations24,25.

An important goal in controlling the angular momentum is not only to induce a torque at ultrashort times but also to be able to amplify or suppress the torque oscillations. It is the purpose of this work to show how to induce and manipulate at will the precession of the magnetization using a sequence of two or three acoustic pulses which are generated by femtosecond optical pulses. The ferromagnetic material is a nickel film but it can be any ferromagnetic or ferrimagnetic structure as long as the material has a large magnetostriction. Importantly, we study the precise conditions for such control by choosing the appropriate amplitudes and time delays between the pulses. The effect of the shapes of the acoustic pulses are also considered as, either unipolar or bipolar pulse can be generated via the lattice compression and expansion propagating in the magnetic material. To explain the effect of each particular sequence of acoustic pulses and the corresponding control of angular momentum, we make a formal analogy between the controlled motion of precession and a two dimensional pendulum subject to momentum kicks provided by the acoustic pulses. The trajectory of the magnetic vector results from both the change of the frequency of the corresponding pendulum and the amplitude of the torque. The model considers either unipolar and bipolar Crenel function pulses or realistic strain pulses. We first describe the control of the magnetization by two pulses and its pendulum analogy. Then we describe the case of three pulses, the pendulum analogy being further discussed in the supplementary information (SI). Finally we briefly discuss the effect of the pulse shapes which is also detailed in the (SI).

Results and Discussion

Experimental configuration and sample description

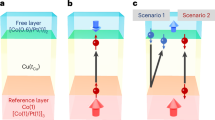

The experiment was performed by exciting the front side of Ni films using sequences of femtosecond pump pulses with controlled time delays and detecting the reflectivity and magnetization dynamics on the back side through a substrate using probe pulses, by means of the time-resolved pump-probe technique. Figure 1a is a sketch of the experimental configuration. The femtosecond pump pulses (60 fs, 400 nm) give rise to a thermal expansion of the lattice, which produces acoustic pulses in the front side of Ni. While propagating through the film, they bring about a modification of the magneto-crystalline anisotropy via a magnetostriction which takes place during the acoustic pulse, therefore initiating a precession of the magnetization vector. The probe pulses (40 fs, 800 nm) have an incident angle of 10° and measure both the transient differential reflectivity ΔR(t) and the differential magneto-optical polar Kerr rotation ΔθK(t) on the back side as a function of the time delay t between a pump and probe. The signals are measured with a synchronous detection scheme9. We used a poly-crystalline 350-nm-thick Ni film deposited on a sapphire substrate by magnetron sputtering, which has the good acoustic impedance match for the purpose of the experiment (~10% of an acoustic pulse is reflected). The external magnetic field was chosen to be Hext = 0.36 T with an angle of 44° with respect to the normal to the sample plane. In Fig. 1a T12 (respectively T23) represent the delays between pulses 1 and 2 (respectively 2 and 3). As shown hereafter, it is convenient to define the temporal quantities  and

and  , Tprec being the period of the precession (74 ps in the following). It allows referring to a particular number of full rotations labeled by (n). We also define the total energy density Ei of the i-th pump pulse as well as their ratio βij = Ei/Ej(i, j = 1, 2, 3). Figure 1b sets the definition of spherical coordinates (θ, ϕ) and their corresponding small variations(δθ, δϕ) for the motion of precession as used hereafter,

, Tprec being the period of the precession (74 ps in the following). It allows referring to a particular number of full rotations labeled by (n). We also define the total energy density Ei of the i-th pump pulse as well as their ratio βij = Ei/Ej(i, j = 1, 2, 3). Figure 1b sets the definition of spherical coordinates (θ, ϕ) and their corresponding small variations(δθ, δϕ) for the motion of precession as used hereafter,  being respectively the magnetization vector and the effective field. The sample is assumed to be in the (xOy) plane and the magnetization initially points along (θ0 ≈ π/2, ϕ = 0) in the (xOz) plane.

being respectively the magnetization vector and the effective field. The sample is assumed to be in the (xOy) plane and the magnetization initially points along (θ0 ≈ π/2, ϕ = 0) in the (xOz) plane.

Control of the magnetization dynamics with a sequence of two acoustic pulses: amplification or suppression of the precession

Experimental data

Let us first focus on a sequence of two independent acoustic pulses. The excitation pulse which is centered at t = 0 ps initiates the precession of the magnetization via magnetostriction and the control pulse, which arrives after at T12, modifies the trajectory of the precession which projection on the normal to the sample is observed via the rotation ΔθK(t). The change of reflectivity ΔR(t) normalized to its static value RS is represented in Fig. 2a in the case of excitation by the pulse 1 only (upper curve), therefore showing the effect of the acoustic strain as detailed in Ref. 21. An example of a detailed sequence of two pump pulses is also shown both for ΔR(t) and ΔθK(t). In Fig. 2b the ΔθK(t) curves correspond to various delays T12 ( ). The dashed line, which corresponds to the case of only one pump pulse, serves as a temporal reference. Clearly the oscillations of the precession are suppressed for

). The dashed line, which corresponds to the case of only one pump pulse, serves as a temporal reference. Clearly the oscillations of the precession are suppressed for  and are nearly doubled for

and are nearly doubled for  . In Fig. 2c the ΔθK(t) curves correspond to various amplitudes β12 (β12 = 0, 0.7, 1, 1.3) in the case of a fixed T12 = 7Tprec/2 = 259 ps (note the broken scale in the temporal axis). A detailed view of the effect of varying

. In Fig. 2c the ΔθK(t) curves correspond to various amplitudes β12 (β12 = 0, 0.7, 1, 1.3) in the case of a fixed T12 = 7Tprec/2 = 259 ps (note the broken scale in the temporal axis). A detailed view of the effect of varying  for β12 = 1 is provided in Fig. 2d by a two-dimensional mapping of the contrast of the oscillations as a function of time t and

for β12 = 1 is provided in Fig. 2d by a two-dimensional mapping of the contrast of the oscillations as a function of time t and  (still with Tprec = 74 ps). Interestingly, the phase of the oscillations displays an abrupt change of π in the vicinity of

(still with Tprec = 74 ps). Interestingly, the phase of the oscillations displays an abrupt change of π in the vicinity of  as seen by the opposite contrasts of colors for a fixed time t when

as seen by the opposite contrasts of colors for a fixed time t when  increases. As seen in Fig. 2c this abrupt change of π in the phase of the precession also occurs when β12 is varied across the value 1. For long delays like T12 = 7Tprec/2 (

increases. As seen in Fig. 2c this abrupt change of π in the phase of the precession also occurs when β12 is varied across the value 1. For long delays like T12 = 7Tprec/2 ( ) the precession is already significantly damped. Therefore, the value β12 = 1 has to be changed so that the motion of precession is exactly suppressed for

) the precession is already significantly damped. Therefore, the value β12 = 1 has to be changed so that the motion of precession is exactly suppressed for  . Summarizing the results, for a sequence of two pump pulses, the torque can be controlled such that the precession is suppressed for

. Summarizing the results, for a sequence of two pump pulses, the torque can be controlled such that the precession is suppressed for  and amplified for

and amplified for  , β12 being finely adjusted near 1 to compensate for the damping.

, β12 being finely adjusted near 1 to compensate for the damping.

Control of magnetization dynamics with two acoustic pump pulses.

(a) Differential reflectivity ΔR/Rs with one and two pulses (top two curves) and differential Kerr signal ΔθK for two pulses (lower curve) showing the timing sequence. (b) ΔθK for various delays  between pulses 1 and 2 with equal energy (β12 = 1). Dotted curve: reference signal obtained with one acoustic pump pulse. For

between pulses 1 and 2 with equal energy (β12 = 1). Dotted curve: reference signal obtained with one acoustic pump pulse. For  (

( ): suppression (amplification) of precession. (c) ΔθK for various β12 for the fixed delay

): suppression (amplification) of precession. (c) ΔθK for various β12 for the fixed delay  . For β12 = 1: suppression of precession. (d) Two dimensional mapping of ΔθK versus time t and

. For β12 = 1: suppression of precession. (d) Two dimensional mapping of ΔθK versus time t and  . The suppression (or amplification) of precession occur for

. The suppression (or amplification) of precession occur for  (or 1/2). The increment in

(or 1/2). The increment in  is 4 ps.

is 4 ps.

Theoretical analysis

Before considering a sequence of three pulses, let us analyze the preceding controlled behavior of the motion of precession in terms of amplitude and phase variations of the magnetic angular momentum. Towards that purpose we use the representation displayed in Fig. 3 where the precession of magnetization sketched in Fig. 1b is projected onto the (yOz) plane. As derived in section 1 of the (SI), the equations of motion for small angle deviations (δθ, δϕ) around the equilibrium (θ0, 0) are:

K(t) = Kaz(t) + Ksz(t) is an effective anisotropy corresponding to the magneto-crystalline Kaz(t) and strain Ksz(t) anisotropies perturbed by the acoustic pulses, Ms, Hx, Hz and γ are the magnetization at saturation, the x and z components of the external field and the gyromagnetic factor. Figure 3a shows the trajectory in the (δθ, δϕ) plane (equivalently (yOz)) due to a sequence of two delta-function pulses, starting from the equilibrium (center at t = 0). Because the first acoustic pulse modifies the anisotropy along Oz, angular momentum is acquired in δϕand the precession results on the circle C1, as indicated by the arrow, at a frequency  . The radius of this circle corresponds to the amplitude of the precession about the static effective field

. The radius of this circle corresponds to the amplitude of the precession about the static effective field  , i.e. in equilibrium. For a given time delay T12, the second pulse abruptly modifies the trajectory of

, i.e. in equilibrium. For a given time delay T12, the second pulse abruptly modifies the trajectory of  which continues its motion of precession with a smaller amplitude on the inner circle C2 and with a different phase. If the second acoustic pulse arrives at a later time

which continues its motion of precession with a smaller amplitude on the inner circle C2 and with a different phase. If the second acoustic pulse arrives at a later time  , the trajectory evolves on the outer circle

, the trajectory evolves on the outer circle  corresponding to a larger amplitude of the precession. As discussed in section 1 of the (SI), the real trajectories are more elliptical as the angular momentum goes to δϕ. In addition it slightly deviates from an ellipse because the tip of the magnetization evolves along the edges of a saddle shape. Two sequences of times are of particular interest as shown in Fig. 3b: the cases T12 = Tprec/2 (or

corresponding to a larger amplitude of the precession. As discussed in section 1 of the (SI), the real trajectories are more elliptical as the angular momentum goes to δϕ. In addition it slightly deviates from an ellipse because the tip of the magnetization evolves along the edges of a saddle shape. Two sequences of times are of particular interest as shown in Fig. 3b: the cases T12 = Tprec/2 (or  ) and T12 = Tprec (or

) and T12 = Tprec (or  ) lead respectively to the suppression and to the maximum amplification of the motion of precession. Experimentally, they correspond to

) lead respectively to the suppression and to the maximum amplification of the motion of precession. Experimentally, they correspond to  and

and  in Fig. 2b. They also show up in the experimental mapping displayed in Fig. 2d in the vicinity of

in Fig. 2b. They also show up in the experimental mapping displayed in Fig. 2d in the vicinity of  where the contrast changes abruptly and near

where the contrast changes abruptly and near  where the contrast is enhanced for a given time delay.

where the contrast is enhanced for a given time delay.

Schematic representation of controlled magnetization trajectory by two acoustic pulses, based on the pendulum analogy.

(a) Trajectory corresponding to a decrease (full curve and circle C2) or an increase (dotted curve and circle C2') of the precession amplitude. (b) Trajectory corresponding to a full suppression (T12 = Tprec/2) and maximum amplification (T12 = Tprec) of the precession amplitude. (c) Trajectory showing the effect of pulse duration τp.

The preceding graphical representation can be easily carried on when the acoustic pulses have a finite duration τp. As shown in Fig. 3c the trajectories also evolve along the C1 and C2 circles which are reached after an elapse of time. By making the analogy between equation (1) and the motion of a pendulum we show in section 1 of the (SI) that:

This solution is obtained for an anisotropy K(t) which has a Crenel temporal shape of duration τpwith an amplitude  . As discussed in detail in section 1 of the (SI), the elapse time is equal to τp, the particular precession amplitudes () occur for T12 = (Tprec/4) + (τp/2) and more importantly, with a second identical pulse the suppression of the motion of precession occurs for:

. As discussed in detail in section 1 of the (SI), the elapse time is equal to τp, the particular precession amplitudes () occur for T12 = (Tprec/4) + (τp/2) and more importantly, with a second identical pulse the suppression of the motion of precession occurs for:

The equality is obtained for delta-function pulses.

In the preceding analysis we have excluded any thermal effects since for thick metallic films, as the one used here (350 nm), the heat diffusion on the backside of the film leads to a slow exponential increase of the temperature in the time scale larger than 300 ps that is much larger than the precession period. Precisely this exponential temperature raise has been quantified to be ~10 K after ~400 ps in the case of 200 nm thick Ni film.

Control of the magnetization dynamics with a sequence of three acoustic pulses: arbitrary choice of the timing for the precession control

Experimental data

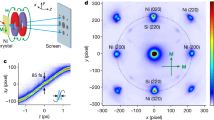

So far, we have employed two sequential acoustic pulses to control coherently the magnetization  . The constraint imposed by equation (4) is however restrictive as ultimately one would like to manipulate (stop or amplify) the precession at any time. In addition, in some cases acoustic pulses can have different shapes such as when generated from different generator transducers26 or pump lasers with different photon energies27. Also, other acoustic modes with different shapes can be produced with one pump pulse28,29. Moreover, the acoustic pulse can modify its shape during propagation as a result of phonon dispersion and nonlinearity30,31. Therefore, it is important to find the conditions for a complete control of the magnetization precession, independently of the pulse shape and independently of the particular precession frequency 2π/Tprec of the ferromagnetic medium as imposed by equation (4). We achieved such control with a sequence of three pulses. In the following, three pulses are considered with respective time delays T12 and T23 which can be varied independently as well as the ratios βij(i, j = 1, 2, 3). In Fig. 4a, the ΔθK(t) curves correspond to various delays T12 and T23. The temporal sequence is chosen such that the motion of precession is well contrasted and distinct from the excitation pulse. For that purpose the delays T12 are varied near 3Tprec/2, i.e. after one full revolution in the (δθ, δϕ) plane (equivalently (yOz)) has occurred. Therefore it is convenient to use the relative delays

. The constraint imposed by equation (4) is however restrictive as ultimately one would like to manipulate (stop or amplify) the precession at any time. In addition, in some cases acoustic pulses can have different shapes such as when generated from different generator transducers26 or pump lasers with different photon energies27. Also, other acoustic modes with different shapes can be produced with one pump pulse28,29. Moreover, the acoustic pulse can modify its shape during propagation as a result of phonon dispersion and nonlinearity30,31. Therefore, it is important to find the conditions for a complete control of the magnetization precession, independently of the pulse shape and independently of the particular precession frequency 2π/Tprec of the ferromagnetic medium as imposed by equation (4). We achieved such control with a sequence of three pulses. In the following, three pulses are considered with respective time delays T12 and T23 which can be varied independently as well as the ratios βij(i, j = 1, 2, 3). In Fig. 4a, the ΔθK(t) curves correspond to various delays T12 and T23. The temporal sequence is chosen such that the motion of precession is well contrasted and distinct from the excitation pulse. For that purpose the delays T12 are varied near 3Tprec/2, i.e. after one full revolution in the (δθ, δϕ) plane (equivalently (yOz)) has occurred. Therefore it is convenient to use the relative delays  and

and  which is varied in a broad range (

which is varied in a broad range ( ) that covers more than half of a precession period (37 ps). Correspondingly, we search for the values

) that covers more than half of a precession period (37 ps). Correspondingly, we search for the values  for which the precession is suppressed. In Fig. 4a, pulses 2 and 3 have the same amplitudes (β23 = 1) and the arrival time of the second pulse is indicated by the arrows. Clearly the constraint imposed by equation (4) is released. Instead, we can determine a relationship between the delays

for which the precession is suppressed. In Fig. 4a, pulses 2 and 3 have the same amplitudes (β23 = 1) and the arrival time of the second pulse is indicated by the arrows. Clearly the constraint imposed by equation (4) is released. Instead, we can determine a relationship between the delays  and

and  to control the precession. This is represented in Fig. 4b where we find that:

to control the precession. This is represented in Fig. 4b where we find that:

Control of magnetization dynamics with three acoustic pump pulses.

(a) ΔθK for various delays T12 and T23 (for β23 = 1). Fixing T23 arbitrarily T12 is adjusted to always suppress the precession. (b) Relation between  and

and  (for β23 = 1) for suppressing the precession and controlling the phase (advanced: upper curves; retarded: lower curves). Open circle: experimental results; rectangle, circle and triangle: theoretical results for different conditions of Gilbert damping α and acoustic reflection coefficient rac. Rectangles: (α = 0.037; rac = 0.1); triangles: (α = 0.037; rac = 0); circles: (α = 0; rac = 0; dashed lines: equation (6). Inset: effective strain pulse η(t) (dashed line), differential reflectivity (closed circles: measured; full line: calculated). (c) Schematic representation of controlled magnetization trajectory by three acoustic pulses leading to equation (6). The trajectory (full curve) is chosen to suppress the precession.

(for β23 = 1) for suppressing the precession and controlling the phase (advanced: upper curves; retarded: lower curves). Open circle: experimental results; rectangle, circle and triangle: theoretical results for different conditions of Gilbert damping α and acoustic reflection coefficient rac. Rectangles: (α = 0.037; rac = 0.1); triangles: (α = 0.037; rac = 0); circles: (α = 0; rac = 0; dashed lines: equation (6). Inset: effective strain pulse η(t) (dashed line), differential reflectivity (closed circles: measured; full line: calculated). (c) Schematic representation of controlled magnetization trajectory by three acoustic pulses leading to equation (6). The trajectory (full curve) is chosen to suppress the precession.

Theoretical analysis

The linear variation with slope −1/2 given by equation (5) allows setting the timing for the second and third acoustic pulses to suppress the precession of the magnetization at any time. It can also be deduced from the motion of a pendulum as derived in section 2 of the (SI). The jump corresponds to a phase shift which can be controlled to be negative (retarded phase lower curve) or positive (advanced phase in upper curve) by choosing appropriately the delay T23 between the pump pulses 2 and 3.

The constraint β23 = 1 is not necessary. The most general configuration that can be envisaged is represented in Fig. 4c. A sequence of pulses with different amplitudes and time delays is displayed so that at the end of pulse 3, the precession is suppressed (follow the trajectory). Considering the triangle OAB, the cosine and sine rules lead to:

Therefore one may arbitrarily choose a sequence of pulses and amplitudes to stop the precession providing that equation (6) is fulfilled. Two particular cases are interesting and summarized in equations (7): 1) the suppression of precession occurs after an advanced or a retarded phase shift (first column in equation (7)); 2) the amplification of precession occurs after an advanced or a retarded phase shift (second column in equation (7)). E2 = E3 (or β23 = 1) (the case of our experiment):

Let us now study the influence on the temporal delays T12 and T23 of additional effects like the presence of acoustic echoes reflected back and forth in the ferromagnetic film, as well as the damping of the precession. In particular, let us focus on the slight discrepancy at the origin in Fig. 4b ( for

for  ). For that purpose, we performed simulations of the magnetization dynamics using the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation taking into consideration the magnetoelastic energy term: Eme = −3/2λsσscos2θ where λs is the magnetostriction coefficient of a polycrystalline Ni film, σs = 3Bη(1 − ν)/(1 + ν) the stress, B the Bulk modulus, ν the Poisson's ratio and η the strain profile. The modelling is further detailed in section 3 of the (SI). In the inset of Fig. 4b, the strain pulse η(t) (dashed line), defined as an effective quantity as reported in Ref. 21, is shown. It is obtained after fitting the transient reflectivity (solid line) from the experimental results ΔR(t)/Rs (closed circle). The curve with squares in Fig. 4b is obtained for a Gilbert damping α = 0.037 obtained by fitting the experimental results. The acoustic echoes have been included with rac = 0.1. For the triangles, the acoustic echoes are excluded (α = 0.037; rac = 0) and for the closed circles the acoustic echo and the Gilbert damping are both ignored (α = 0; rac = 0). From these graphs, it is clear that the offset can be partly attributed to the Gilbert damping which results in an offset of ~1.3 ps.

). For that purpose, we performed simulations of the magnetization dynamics using the Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert equation taking into consideration the magnetoelastic energy term: Eme = −3/2λsσscos2θ where λs is the magnetostriction coefficient of a polycrystalline Ni film, σs = 3Bη(1 − ν)/(1 + ν) the stress, B the Bulk modulus, ν the Poisson's ratio and η the strain profile. The modelling is further detailed in section 3 of the (SI). In the inset of Fig. 4b, the strain pulse η(t) (dashed line), defined as an effective quantity as reported in Ref. 21, is shown. It is obtained after fitting the transient reflectivity (solid line) from the experimental results ΔR(t)/Rs (closed circle). The curve with squares in Fig. 4b is obtained for a Gilbert damping α = 0.037 obtained by fitting the experimental results. The acoustic echoes have been included with rac = 0.1. For the triangles, the acoustic echoes are excluded (α = 0.037; rac = 0) and for the closed circles the acoustic echo and the Gilbert damping are both ignored (α = 0; rac = 0). From these graphs, it is clear that the offset can be partly attributed to the Gilbert damping which results in an offset of ~1.3 ps.

The preceding study shows that the control of the magnetization dynamics with acoustic pulses depends on the two delays  and

and  which values allow determining for example the cancellation of the precession as shown in Fig. 4b or its amplification. Let us stress that the particular individual shape of the acoustic pulses is not relevant as long as they are shorter than Tprec. Only their relative delays and amplitudes can serve the purpose of controlling the magnetization vector via the change of the magneto-elastic anisotropy. To precise this concept, which is of major importance for applications, we have studied the effect of unipolar and bipolar shaped acoustic pulses on the magnetization trajectory. Figure 5a shows curves simulating the precession dynamics of magnetization induced by differently shaped acoustic pulses. The solid line corresponds to the precession of magnetization triggered by a 10 ps-long unipolar square pulse and the dashed line by a 20 ps-long bipolar squared one. The temporal delay δT between the two pulses is adjusted such that the two motions of precession are equal. When two pulses are used (dashed lines in Fig. 5b) clearly only the delay δT is important for the coherent control of the magnetization and not the detailed pulse shape as highlighted in the grey square. The first curve (full line) results from two unipolar pulses. The second curve (dashed one) corresponds to a unipolar excitation and bipolar control pulse. Only the delay δT determines when the suppression of the precession occurs. Overall, the conditions of coherent control can be determined by choosing the delay such that: T = mTprec + δT for the amplification and T = (m + 1/2)Tprec + δT for the suppression of the precession of magnetization.

which values allow determining for example the cancellation of the precession as shown in Fig. 4b or its amplification. Let us stress that the particular individual shape of the acoustic pulses is not relevant as long as they are shorter than Tprec. Only their relative delays and amplitudes can serve the purpose of controlling the magnetization vector via the change of the magneto-elastic anisotropy. To precise this concept, which is of major importance for applications, we have studied the effect of unipolar and bipolar shaped acoustic pulses on the magnetization trajectory. Figure 5a shows curves simulating the precession dynamics of magnetization induced by differently shaped acoustic pulses. The solid line corresponds to the precession of magnetization triggered by a 10 ps-long unipolar square pulse and the dashed line by a 20 ps-long bipolar squared one. The temporal delay δT between the two pulses is adjusted such that the two motions of precession are equal. When two pulses are used (dashed lines in Fig. 5b) clearly only the delay δT is important for the coherent control of the magnetization and not the detailed pulse shape as highlighted in the grey square. The first curve (full line) results from two unipolar pulses. The second curve (dashed one) corresponds to a unipolar excitation and bipolar control pulse. Only the delay δT determines when the suppression of the precession occurs. Overall, the conditions of coherent control can be determined by choosing the delay such that: T = mTprec + δT for the amplification and T = (m + 1/2)Tprec + δT for the suppression of the precession of magnetization.

Control of magnetization precession with unipolar and bipolar pulses.

(a) Modelling of the precession of magnetization induced by unipolar (full curve) and bipolar (dashed curve) pulses separated by the delay δT. (b) Coherent control of the magnetization precession with sequences of: two unipolar pulses (top full curve) and unipolar + bipolar pulses (lower dashed curve). Only the delays and amplitudes are important for the control (not the shape).

Conclusion

We show that a sequence of two or three acoustic pulses is well adapted for controlling the spin torques in ferromagnetic materials, resulting either in the suppression or the amplification of the magnetization precession. When using two acoustic pulses, the control is somehow more restrictive because the occurrence of suppression or amplification is directly related to integers of half ( ) or full precession periods (

) or full precession periods ( ), quantities that strongly depend on the intrinsic material properties. However, in the case of three acoustic pulses, arbitrary delays T12, T23 and amplitudes Ei(i = 1,2,3) can be used providing that equation (6) is satisfied. The second and third pulses then act as a single pulse which shape can be modified at will. A simple graphical representation of the magnetization trajectory follows. This picture is validated in the framework of the motion of a two dimensional pendulum subject to external pulsed perturbations. A full Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert modelling of the dynamics, including the time dependent anisotropy resulting from the magneto-elastic changes induced by the acoustic strain, also provides the detailed influence of the material properties such as the precession damping. The consequences of this work are important whenever a precise control of the magnetization dynamics is desired. This is the case for example in spintronics for controlling spin torques but it can also be used for fundamental studies related to the lattice dynamics of materials particular when several individual modes co-exist. Let us finely emphasize that even though the duration of acoustic pulses is in the terahertz range, the control of the magnetization dynamics can be performed with an extreme precision as it is related to the time delays of the acoustic pulses, themselves generated by femtosecond optical pulses.

), quantities that strongly depend on the intrinsic material properties. However, in the case of three acoustic pulses, arbitrary delays T12, T23 and amplitudes Ei(i = 1,2,3) can be used providing that equation (6) is satisfied. The second and third pulses then act as a single pulse which shape can be modified at will. A simple graphical representation of the magnetization trajectory follows. This picture is validated in the framework of the motion of a two dimensional pendulum subject to external pulsed perturbations. A full Landau-Lifshitz-Gilbert modelling of the dynamics, including the time dependent anisotropy resulting from the magneto-elastic changes induced by the acoustic strain, also provides the detailed influence of the material properties such as the precession damping. The consequences of this work are important whenever a precise control of the magnetization dynamics is desired. This is the case for example in spintronics for controlling spin torques but it can also be used for fundamental studies related to the lattice dynamics of materials particular when several individual modes co-exist. Let us finely emphasize that even though the duration of acoustic pulses is in the terahertz range, the control of the magnetization dynamics can be performed with an extreme precision as it is related to the time delays of the acoustic pulses, themselves generated by femtosecond optical pulses.

References

Beaurepaire, E., Merle, J.–C., Daunois, A. & Bigot, J.–Y. Ultrafast spin dynamics in ferromagnetic nickel. Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 4250–4253 (1996).

Koopmans, B., van Kampen, M., Kohlhepp, J. T. & de Jonge, W. J. M. Ultrafast magneto-optics in nickel: Magnetism or optics? Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 844–847 (2000).

van Kampen, M. et al. All-optical probe of coherent spin waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 227201 (2002).

Guidoni, L., Beaurepaire, E. & Bigot, J.–Y. Magneto-optics in the ultrafast regime: Thermalization of spin populations in ferromagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 17401 (2002).

Vomir, M., Andrade, L. H. F., Guidoni, L., Beaurepaire, E. & Bigot, J.–Y. Real space trajectory of the ultrafast magnetization dynamics in ferromagnetic metals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 237601 (2005).

Bigot, J.–Y., Vomir, M., Andrade, L. H. F. & Beaurepaire, E. Ultrafast magnetization dynamics in ferromagnetic cobalt: The role of the anisotropy. Chem. Phys. 318, 137–146 (2005).

Kimel, A. V., Kirilyuk, A., Usachev, P. A., Balbashov, A. M. & Rasing, Th. Ultrafast non-thermal control of magnetization by instantaneous photomagnetic pulses. Nature 435, 655–657 (2005).

Malinowski, G. et al. Control of speed and efficiency of ultrafast demagnetization by direct transfer of spin angular momentum. Nature Phys. 4, 855–858 (2008).

Bigot, J.–Y., Vomir, M. & Beaurepaire, E. Coherent ultrafast magnetism induced by femtosecond laser pulses. Nature Phys. 5, 515–520 (2009).

Radu, I. et al. Laser-induced magnetization dynamics of lanthanide-doped permalloy thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 117201 (2009).

Boeglin, C. et al. Distinguishing the ultrafast dynamics of spin and orbital moments in solids. Nature 465, 458–462 (2010).

Radu, I. et al. Transient ferromagnetic-like state mediating ultrafast reversal of antiferromagnetically coupled spins. Nature 472, 205–208 (2011).

Rudolf, D. et al. Ultrafast magnetization enhancement in metallic multilayers driven by superdiffusive spin current. Nature Commun. 3, 1037 (2012).

Zhang, Q., Nurmikko, A. V., Anguelouch, A., Xiao, G. & Gupta, A. Coherent magnetization rotation and phase control by ultrashort optical pulses in CrO2 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 177402 (2002).

Scherbakov, A. V. et al. Coherent magnetization precession in ferromagnetic (Ga,Mn)As induced by picosecond acoustic pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 117204 (2010).

Kampfrath, T. et al. Coherent terahertz control of antiferromagnetic spin waves. Nature Photon. 5, 31–34 (2011).

Kanda, N. et al. The vectorial control of magnetization by light. Nature Commun. 2, 362 (2011).

Berezovsky, J., Mikkelsen, M. H., Stoltz, N. G., Coldren, L. A. & Awschalom, D. D. Picosecond coherent optical manipulation of a single electron spin in a quantum dot. Science 320, 349 (2008).

Hansteen, F., Kimel, A., Kirilyuk, A. & Rasing, Th. Nonthermal ultrafast optical control of the magnetization in garnet films. Phys. Rev. B 73, 014421 (2006).

Kirilyuk, A., Kimel, A. V. & Rasing, Th. Ultrafast optical manipulation of magnetic order. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 2731–2784 (2010).

Kim, J.–W., Vomir, M. & Bigot, J.–Y. Ultrafast magnetoacoustics in nickel films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 166601 (2012).

Mangin, S. et al. Current-induced magnetization reversal in nanopillars with perpendicular anisotropy. Nature Mater. 5, 210–215 (2006).

Houssameddine, D. et al. Spin-torque oscillator using a perpendicular polarizer and a planar free layer. Nature Mater. 6, 447–453 (2007).

Yamaguchi, K., Nakajima, M. & Suemoto, T. Coherent control of spin precession motion with impulsive magnetic fields of half-cycle terahertz radiation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 237201 (2010).

Li, Q., Hoogeboom-Pot, K., Nardi, D., Murnane, M. M. & Kapteyn, H. C. Generation and control of ultrashort-wavelength two-dimensional surface acoustic waves at nanoscale interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 85, 195431 (2012).

Thomsen, C., Grahn, H. T., Maris, H. J. & Tauc, J. Surface generation and detection of phonons by picosecond light pulses. Phys. Rev. B 34, 4129–4138 (1986).

Matsuda, O. & Tachizaki, T. Acoustic phonon generation and detection in GaAs/Al0.3Ga0.7As quantum wells with picosecond laser pulses. Phys. Rev. B 71, 115330 (2005).

Matsuda, O., Wright, O. B., Hurley, D. H., Gusev, V. E. & Shimizu, K. Coherent shear phonon generation and detection with ultrashort optical pulses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 095501 (2004).

Bombeck, M. et al. Magnetization precession induced by quasitransverse picosecond strain pulses in (311) ferromagnetic (Ga,Mn)As. Phys. Rev. B 87, 060302(R) (2013).

Hao, H.–Y. & Maris, H. J. Experiments with acoustic solitons in crystalline solids. Phys. Rev. B 64, 064302 (2001).

Temnov, V. V. et al. Femtosecond nonlinear ultrasonics in gold probed with ultrashort surface plasmons. Nature Commun. 4, 1468 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support of the European Research Council for the Advanced Grant “ATOMAG” ERC-2009-AdG-20090325#247452.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.-W.K. did the experiments, prepared figures 2 to 5 and SI-2, did the numerical simulations for figure SI-2 and participated to the writing of the main manuscript. M.V. participated to the experiments. J.-Y.B. did the modelling and wrote the main manuscript and the supplementary information and did figures 1, 4 and SI-1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder in order to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, JW., Vomir, M. & Bigot, JY. Controlling the Spins Angular Momentum in Ferromagnets with Sequences of Picosecond Acoustic Pulses. Sci Rep 5, 8511 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08511

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep08511

This article is cited by

-

Generation of spin waves by a train of fs-laser pulses: a novel approach for tuning magnon wavelength

Scientific Reports (2017)

-

Terahertz modulation of the Faraday rotation by laser pulses via the optical Kerr effect

Nature Photonics (2016)

-

Nonlinear optics rules magnetism

Nature Photonics (2016)